Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Markerless camera-based motion capture systems (MCBSs) for ergonomic risk assessment in industrial settings offer substantial accuracy and reliability.

- Markerless systems (MCBSs) provide a feasible, scalable alternative to traditional ergonomic methods.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Markerless systems (MCBSs) have strong potential for practical, real-world applications and automation.

- Markerless systems (MCBS) support Industry 5.0 goals in occupational risk prevention.

Abstract

Ergonomic risk assessment is crucial for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs), which often arise from repetitive tasks, prolonged sitting, and load handling, leading to absenteeism and increased healthcare costs. Biomechanical risk assessment, such as RULA/REBA, is increasingly being enhanced by camera-based motion capture systems, either marker-based (MBSs) or markerless systems (MCBSs). This systematic review compared MBSs and MCBSs regarding accuracy, validity, and reliability for industrial ergonomic risk analysis. A comprehensive search of PubMed, WoS, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, and PEDro (31 May 2025) identified 898 records; after screening with PICO-based eligibility criteria, 20 quantitative studies were included. Methodological quality was assessed with the COSMIN Risk of Bias tool, synthesized using PRISMA 2020, and graded with EBRO criteria. MBSs showed the highest precision (0.5–1.5 mm error) and reliability (ICC > 0.90) but were limited by cost and laboratory constraints. MCBSs demonstrated moderate-to-high accuracy (5–20 mm error; mean joint-angle error: 2.31° ± 4.00°) and good reliability (ICC > 0.80), with greater practicality in field settings. Several studies reported strong validity for RULA/REBA prediction (accuracy up to 89%, κ = 0.71). In conclusion, MCBSs provide a feasible, scalable alternative to traditional ergonomic assessment, combining reliability with usability and supporting integration into occupational risk prevention.

1. Introduction

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are one of the main problems affecting workers in industrial scenarios [1,2]. These are often caused by prolonged sitting, repetitive tasks, handling loads, and the use of vibrating tools [3]. These factors contribute substantially to absenteeism, reduced productivity, and increased healthcare costs. Industry 5.0 is adapting risk analysis tools to prevent WMSD risks [4] using observational methods such as Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA) [5] and Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) [6] with or without camera-based technologies, including marker-based (MBSs) and markerless systems (MCBSs) [7], to score WMSD risks. Camera-based tools can help to quantify WMSD risks using information that comes from the kinematics of workers during specific tasks (such as lifting, pulling, etc.) and be combined with traditional observational methods (e.g., RULA and REBA). However, MBSs and MCBSs are different. Marker-based motion capture systems (MBSs) are considered the gold-standard tools [8,9] in biomechanics, although the placement of markers on the body is time-consuming and sensitive to skin movement artifacts, limiting the natural free movement of workers. In contrast, markerless camera-based motion capture systems (MCBSs) do not require any markers, making their application less time-consuming and preserving natural movements and reducing skin movement artifacts [10]. Therefore, MCBSs can better reflect real-world industrial scenarios while preserving workers’ well-being and performance. Nevertheless, MCBs and MCBSs require the placement of camera-based systems in working scenarios and are less portable compared to wearable mocap inertial systems. However, they have the advantage of being able to reproduce 3D body shapes and even 4D representations (3D + time) for dynamic motion analysis [11]. Studies indicate that MCBSs have accuracy levels comparable to those of traditional methods like the European Assembly Worksheet (EAWS) [12,13]; REBA/RULA; and joint-angle comparisons [14,15], whereby an average deviation of 2.31 ± 4.00° in joint kinematics is observed [16]. In 2018, Mehrizi et al. [16] demonstrated that MCBSs can accurately estimate 3D joint kinematics during symmetrical lifting, though they also acknowledged the need for further validation studies when applying these systems to more complex tasks such as asymmetrical lifting in workplace environments. Comparisons of the Microsoft Kinect V2 (MCBS) and Vicon Bonita (MBS) systems demonstrate that while MBSs are more accurate, some movements (e.g., trunk inclination) are estimated well by markerless alternatives, showing divergences of 2.08° and 3.67°. However, when it comes to compound motions, for example, arm anteversion with external rotation and axial rotation, these levels of precision start to diminish [17]. Notwithstanding their limitations, MCBSs enhance efficiency by curtailing dependence on direct observation and improving posture evaluation. In ergonomic assessments, MCBSs have shown a high accuracy level for screening upper limb movements, providing excellent inter-rater reliability for shoulder motions (ICC ≥ 0.97) and strong agreement for thoracic rotation (ICC = 0.92) [18]. However, assessments of knee valgus have demonstrated moderate reliability (ICC = 0.59–0.82), raising uncertainties regarding the accuracy of lower limb evaluations [19]. The validity of MCBSs in gait analysis has also been assessed recently, producing good agreement in sagittal plane kinematics but moderate reliability in coronal and transverse planes (ICC = 0.520–0.608) [20]. Although MBS approaches stand out for their accuracy, MCBSs offer flexibility and non-intrusiveness and provide clinical and workplace improvements. They enable objective movement assessment, real-time feedback, and customized interventions [7]. Furthermore, integrating motion capture with virtual reality increases engagement in rehabilitation and ergonomic training and enables virtual workplace prototyping with quantitative ergonomic risk assessment [21]. Despite all these advancements, certain gaps still exist in terms of accuracy, validity, and reliability, and they are the objective of this systematic review.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement [22]. A structured protocol based on the PICO framework (see Table 1) was used to define inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring transparency and methodological consistency. This systematic review is registered in PROSPERO with the following ID number: CRD420251038205 [23].

Table 1.

Search strategy in PubMed.

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted on 31 May 2025 across five databases: PubMed, Web of Science (WoS), ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). The search strategy integrated Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword combinations relating to ergonomic assessment, motion capture technologies, and measurement outcomes (accuracy, validity, and reliability). Boolean operators (AND/OR) and database-specific filters (e.g., date range, English language, and exclusion of reviews) were applied. The full search strategies are provided in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 2.

Search strategy in WoS.

Table 3.

Search strategy in Science Direct.

Table 4.

Search strategy in IEEE EXplore.

Table 5.

Search strategy in PEDRo.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they (1) involved working-age adults (18–65) performing occupational tasks; (2) used MBSs, MCBSs, or traditional ergonomic assessments; (3) evaluated at least one of the following outcomes: accuracy, validity, or reliability; and (4) used a quantitative study design. Studies were excluded if they were qualitative, were conducted in non-occupational settings, or lacked relevant outcome metrics. Table 6 outlines the detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Table 6.

Eligibility criteria based on the PICO framework.

2.3. Study Selection

Records were imported into EndNote [24] for duplicate removal, followed by two-phase screening in Rayyan [25]. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers; disagreements were resolved through discussion or third-party arbitration. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and reviewed against the inclusion criteria.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a standardized form, including author, year, system type (MBS/MCBS), ergonomic tool used, outcomes measured, and key findings. Accuracy metrics (e.g., RMSE and angle deviation), validity statistics (e.g., Cohen’s kappa (κ) and expert agreement), and reliability scores (e.g., ICCs) were recorded.

2.5. Synthesis and Grading of Evidence

Outcomes were synthesized narratively. No meta-analysis was performed due to heterogeneity in study designs and reporting metrics. The Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) [26,27] was used for methodological quality appraisal. Evidence strength was graded using the Evidence-Based Guideline Development (EBRO) framework [28], based on study quality, consistency, and applicability.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

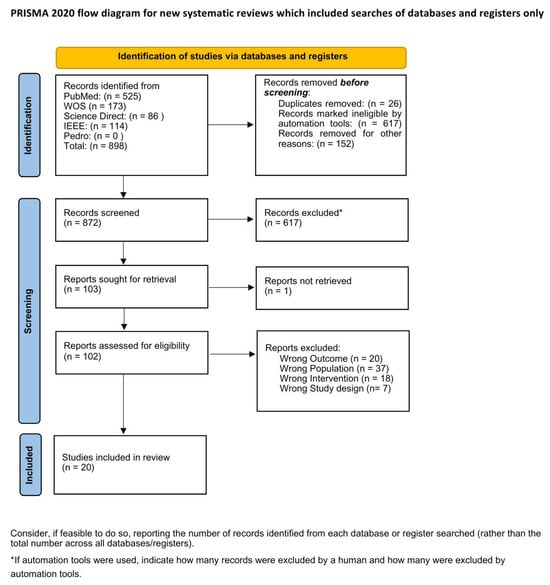

A total of 898 records were identified from five databases: PubMed (525), ScienceDirect (86), Web of Science (173), IEEE Xplore (114), and PEDro (0). After removing 26 duplicates, 872 records remained. A total of 617 records were excluded automatically based on the initial screening, and 152 records were manually excluded. After reviewing 103 records for relevance, all 103 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 1 was not retrievable, and 82 studies were excluded for reasons including incorrect outcomes (20), publication type (7), population (37), and intervention (18). Finally, 20 studies [12,13,14,15,17,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flowchart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The 20 studies included in the review were published between 2013 and 2025, with sample sizes ranging from 1 to 30 participants. Twelve studies included a direct comparison of MCBS technologies (e.g., Kinect, RealSense, and OpenPose) with MBS systems (e.g., Vicon, Optotrak, and BTS) [16,17,30,32,33,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. One study evaluated a computer vision (CV)-based MCBS against a non-CV-based MCBS [31]. Five studies compared MCBSs with traditional ergonomic assessment methods (e.g., NIOSH, OCRA, REBA, EAWS, and RULA) [12,13,14,15,34]. The tasks analyzed ranged from lifting and handling to stationary workstation tasks in different workplace settings.

3.3. Evidence Table

The following table (Table 7) summarizes the study characteristics and key findings of the included studies, along with their measurement domains, such as accuracy, validity, and reliability. This table highlights the interventions used, the comparison methods, and the outcomes measured in each study, providing an overview of the research landscape.

Table 7.

Table of evidence.

3.4. Measurement Evidence Table

The following table (Table 8) summarizes the accuracy, validity, and reliability of the studies included in this review. It shows key metrics such as RMSE, Cohen’s kappa, and reliability statistics (ICCs) for the technologies assessed.

Table 8.

Summary of accuracy, validity, and reliability in included studies.

3.5. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

The methodological quality of the 20 included studies was assessed using the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist, focusing on the evaluation of three measurement domains: reliability, validity, and accuracy. Assessments were performed independently by three reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions.

Most studies demonstrated moderate to high methodological quality, particularly in the domains of accuracy and validity. However, reliability was the most inconsistently reported domain. Only six studies provided statistical reliability measures, such as intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs), with values ranging from 0.70 to 0.99. Several studies referenced reliability qualitatively without formal assessment. Additionally, some studies were downgraded for small sample sizes, unclear statistical methods, or incomplete reporting of ergonomic scoring procedures.

Using COSMIN-based categorization:

- Very Good (V) quality was assigned to five studies [16,29,30,32,43], which employed robust statistical analyses and thorough validation.

- Adequate (A) quality applied to thirteen studies [13,14,15,31,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], generally due to minor limitations such as absence of inter-rater testing.

- Doubtful (D) or Inadequate (I) quality was noted in two studies [12,17], particularly those lacking sufficient methodological transparency or formal validation against reference tools.

A full summary of the risk of bias ratings by measurement of property and study is provided in Table 9.

Table 9.

Summary of risk of bias assessment based on COSMIN tool (I = Inadequate, D = Doubtful, A = Adequate, V = Very Good). (-) indicates that the property was not assessed in the study.

3.6. Results of Individual Studies

Accuracy was reported in 18 studies, with MBSs consistently achieving joint-angle errors below 3°. MCBSs ranged in performance, with joint errors ranging from 4.4 to 23.4 cm (Liu et al. [33]) and RMSE values between 5° and 14° (Van Crombrugge et al. [40], Brunner et al. [17]). Validity was assessed in 19 studies (of which only 17 provided quantitative metrics) through agreement with expert ratings or MBSs. Agreement levels were high, with κ reaching up to 0.71 and the expert score alignment exceeding 70% in several cases. Only six studies addressed reliability statistically, with ICCs ranging from 0.70 to 0.99.

3.7. Summary of Synthesis and Bias

Synthesized findings showed that MBSs provided the highest accuracy and reliability but required controlled lab environments. MCBSs were more accessible and affordable, demonstrating acceptable accuracy and strong validity, particularly in complex dynamic tasks such as asymmetrical lifting and complex combined shoulder motions (e.g., anteversion with external rotation). Studies varied in sample size, ergonomic frameworks, and reporting detail. The risk of bias was lowest in studies that used standardized scoring systems and reference comparisons.

3.8. Reporting Bias

No specific publication bias was detected. However, there may be an overrepresentation of studies with positive findings due to underreporting of failed validation or low-accuracy results.

3.9. Certainty of Evidence

Based on COSMIN [27] and EBRO [28] assessments, the certainty of evidence for the accuracy and validity of outcomes was moderate to high. However, the certainty for reliability was lower due to inconsistent reporting and lack of statistical confirmation in most studies. Using the EBRO classification system [28], the level of evidence for each key measurement property—accuracy, validity, and reliability—was determined based on the number of studies, the methodological quality (assessed via COSMIN [26,27]), and the consistency of the findings across the studies. A total of 20 studies were included in this review, with 18 studies providing quantitative accuracy metrics. Two studies (Eldar, 2020 [15] and Otto et al. [12]) did not report numerical accuracy data and were therefore excluded from the EBRO grading for accuracy (Table 10).

Table 10.

EBRO levels of evidence by outcomes.

Table 10 presents a summary of the EBRO levels of evidence for accuracy, validity, and reliability. It shows the number of studies evaluated for each measurement property, along with the corresponding EBRO levels and the associated certainty levels. Accuracy is rated A2 with a high certainty level, validity is rated B with a moderate certainty level, and reliability is rated C with a low certainty level. These levels reflect both the quantity and consistency of evidence available and should be considered when interpreting the results of this review.

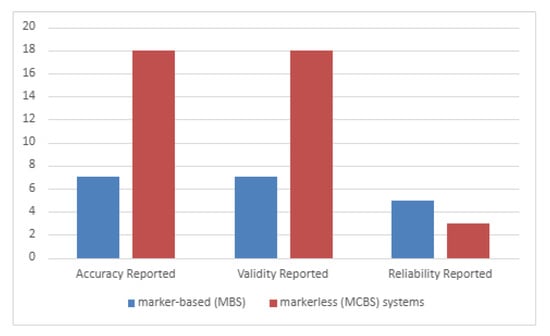

Additionally, in the section below, we provide visual representations of the findings discussed (Table 11, Figure 2)

Table 11.

Reporting of measurement properties across studies.

Figure 2.

Accuracy, validity, and reliability of MBSs and MCBSs in ergonomic assessments.

It is important to note that the counts in Table 10 reflect studies reporting quantitative metrics eligible for EBRO grading; the counts in Table 11 reflect studies that reported accuracy, validity, and reliability in any form (including qualitative descriptions).

Moreover, Figure 2 compares the reporting of accuracy, validity, and reliability for MBSs and MCBSs. MBSs show constantly higher reporting rates for accuracy and reliability, while MCBSs exhibit a lower reporting rate, particularly for reliability. However, in the studies of Eldar et al. [15] and Otto et al. [12], accuracy was not reported.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to compare MBSs and MCBSs for assessing ergonomic risk analysis in terms of their accuracy, validity, and reliability in identifying ergonomic risks in workplace settings. Twenty quantitative studies [12,13,14,15,17,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] were included, with technologies ranging from high-fidelity optical systems to accessible AI-driven, vision-based platforms. The results demonstrate that while MBSs remain the reference gold standard for measurement accuracy, many MCBSs now approach acceptable thresholds for ergonomic evaluation and may offer practical benefits in real-world occupational contexts. These results are consistent with the findings in the previous literature [9,44].

Accuracy was the most consistently evaluated parameter, reported in 18 [13,14,16,17,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] of the 20 included studies. MBSs such as Vicon Bonita and BTS SMART-D consistently achieved joint-angle errors below 3°, with spatial precision in the sub-centimeter range. For example, Mehrizi et al. [16] reported joint-angle deviations of less than 3° when comparing a lifting task analyzed with both MBSs and MCBSs. In 2024, Jiang et al. [32] found that their deep learning model could estimate L5-S1 lumbar loads with RMSE values comparable to biomechanical modeling based on biplanar radiography. MCBSs showed more variability, but several achieved promising results. Moreover, Plantard [37] reported correlation coefficients between Kinect and Vicon joint angles ranging from r = 0.65 to 0.99 and normalized RMSE values for joint torque estimation ranging from 10.6% to 29.8%. Additionally, Liu et al. [33] recorded that 89% of detected joints fell within 20° of their reference markers, with landmark errors ranging from 6 to 12 cm (stereoscopic) and from 6 to 9 cm (ToF). In 2025, Bonakdar et al. [42] demonstrated strong correlations (r ≈ 0.95) and low RMSE values (6.5–9.9°) for hip, knee, and elbow joint angles and a normalized RMSE of ~9% for L5-S1 joint reaction forces compared to marker-based and inertial systems, while achieving 87% agreement in REBA scores. In the same year, Ojelade et al. [43] reported high classification accuracy for manual material handling tasks (≈93%) and hand configurations (≈96–97%), with moderate accuracy for lift origin classification (≈80–84%).

Furthermore, validity was assessed in 19 studies (out of which only 17 reported quantitively) [13,14,15,16,17,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], typically by comparing motion capture outputs with ergonomic risk scores derived from RULA, REBA, EAWS, or expert observers. However, some studies had moderate levels of evidence [12,14,15,36,37,38,41]. In another study, in 2016, Plantard et al. [38] found that RULA scores computed using Kinect data achieved 73–74% agreement with expert assessments in an industrial setting, with κ values ranging from 0.46 to 0.66. Additionally, Bortolini in 2018 [13] demonstrated that EAWS scores could be generated semi-automatically with posture detection using depth cameras, showing strong alignment with expert-coded scoring for postural sections B and C. Similarly, Manghisi et al. [34] developed a real-time AI-based model that produced REBA and EAWS scores with acceptable alignment to expert scorings. Alongside these, Bonakdar et al. [42] reinforced the validity of MCBSs by demonstrating agreement between their markerless system and gold-standard REBA outputs, while Ojelade et al. [43] supported validity through consistent performance across multiple RNN architectures and feature sets. In contrast, some studies, such as Wong et al.’s (2013) [41], relied more on visual comparison than structured validation, limiting confidence in their results.

Lastly, reliability was the least frequently reported measurement property. Only eight studies [16,29,31,32,34,37,42,43] evaluated it, out of which six included statistical evaluations. Plantard et al. (2017) [37] reported intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) ranging from 0.70 to 0.91 for joint angles captured using Kinect under different occlusion conditions. While Mehrizi [35] observed consistent outputs across multiple lifting trials, they did not provide formal reliability metrics. Many studies referenced repeatability or internal consistency without quantifying it [12,14,15,17,38,41]. However, Bonakdar et al. [42] reported high consistency of measurements across repeated trials, while Ojelade et al. demonstrated stable results across cross-validation folds with low variability between runs. Therefore, this lack of reliability testing in the majority of articles, particularly for MCBSs, remains a significant gap regarding their use in longitudinal or compliance-sensitive contexts.

In comparing these systems with traditional ergonomic tools, seven studies [14,15,34,36,37,40,42] evaluated how motion capture-derived outputs aligned with RULA, REBA, EAWS, or NIOSH scores. Most studies found that MCBSs could replicate expert-rated scores in static or semi-structured tasks. For example, Van Crombrugge et al. (2022) [40] achieved R2 values of 0.43 to 0.89 for key postural angles when comparing vision-based estimates with marker-based data. Similarly, Patrizi [36] showed that Kinect-based trunk and limb scores closely matched BTS-based motion capture when applying the NIOSH lifting equation. Traditional methods, while quicker and simpler to administer, were repeatedly shown to suffer from inter-observer variability. On the other hand, motion capture systems, particularly markerless ones enhanced with AI and depth sensing, offered continuous, objective risk detection in environments where observational tools may fall short.

Despite these advances, the evidence has important limitations. Reliability remains significantly underreported. Of the 20 included studies, only three [16,31,37] provided ICCs or similar repeatability metrics, and the majority did not address test–retest consistency at all. Moreover, several studies [12,13,14,17,31,36,40,42,43] used small sample sizes, sometimes fewer than 10 participants, which limits the generalizability of their findings. There was also considerable heterogeneity in study design, sensor placement, scoring systems, and outcome metrics, making it impossible to conduct a formal meta-analysis. As a result, pooled effect estimates and heterogeneity testing could not be performed.

From a methodological standpoint, this review was comprehensive but not without its own limitations. Only studies published in English and available as full texts were included, potentially excluding relevant English research papers. Although the COSMIN tool [27] provided a systematic way to evaluate measurement quality, it was applied across diverse study designs, and in some cases outcome interpretations required inference due to incomplete reporting.

These findings have meaningful implications for workplace ergonomics research. MCBSs, especially those using AI for pose estimation, can be considered suitable for ergonomic screening in structured or moderately complex industrial scenarios.

Their scalability, affordability, and automation potential make them attractive for organizations aiming to adopt continuous worker monitoring. However, accuracy, validity, and reliability must be considered for WMSD risk assessment in the workplace, and this was the objective of this systematic review.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review illustrates that not only are MCBSs advancing technologically, but they are also gaining traction as usable tools for ergonomic risk assessments in work settings. Compared to “observational” assessment tools such as RULA and REBA, MCBSs are more objective and allow for assessments in real time. They have several benefits in terms of accessibility, cost, and scalability, especially in real-world settings where MBSs may not be feasible due to the complexity of their set-up or subject movement. Though MBSs demonstrate more precision in their measurements (often with sub-centimeter and 3° joint-angle errors), their reliance on a controlled lab environment and specialized equipment hinders their generalizability to other contexts.

Markerless technologies that utilize depth-sensor-based and AI-based pose estimation and multi-view markerless reconstruction exhibit promising accuracies of approximately 2.31° ± 4.00° in joint-angle deviation while also demonstrating strong validity in their prediction of ergonomic scores. Most importantly, MCBSs had over 70% agreement with REBA and RULA codes, and reached a κ value of 0.71, suggesting that MCBSs are an effective tool for measurement and quantification of risk factors for ergonomic intervention.

Nonetheless, the review also identifies some important limitations, specifically regarding reliability. Only a few studies reported standardized reliability testing using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), with ICC values ranging from moderate to excellent. The lack of formal reliable assessment results is concerning regarding the use of MCBSs in longitudinal tracking, compliance monitoring, and high-risk jobs, as repeatability is essential in these domains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., S.T., E.F., N.K., M.U.K. and M.F.K.; methodology, S.S., S.T., E.F., N.K., M.U.K. and M.F.K.; validation, S.S., E.F., N.K. and S.T.; formal analysis, E.F., N.K., M.U.K. and M.F.K.; investigation S.S., S.T., E.F., N.K., M.U.K. and M.F.K.; data curation, E.F., N.K. and M.F.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., E.F., N.K., M.U.K. and M.F.K. writing—review and editing, E.F., S.S. and S.T.; visualization, S.S., E.F., N.K., M.U.K. and M.F.K.; supervision, S.S. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All titles and abstracts resulting from the database search were directly imported into Rayyan for screening and management. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to licensing restrictions from the database providers, raw data (i.e., full records retrieved from proprietary databases) cannot be publicly shared.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Pavlovic-Veselinovic, S.; Hedge, A.; Veselinovic, M. An ergonomic expert system for risk assessment of work-related musculo-skeletal disorders. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2016, 53, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janela, D.; Areias, A.C.; Moulder, R.G.; Molinos, M.; Bento, V.; Yanamadala, V.; Correia, F.D.; Costa, F. Recovering Work Productivity in a Population with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: Unveiling the Value and Cost-Savings of a Digital Care Program. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 66, e493–e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğrul, Z.; Mazican, N.; Turk, M. The Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WRMSDs) and Related Factors among Occupational Disease Clinic Patients. Int. Arch. Public Health Community Med. 2019, 3, 030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Hasan, M.R.; Chowdhury, N.I.; Syed, M.A.B.; Farah, M.U. Predictive Health Analysis in Industry 5.0: A Scientometric and Systematic Review of Motion Capture in Construction. Digit. Eng. 2024, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAtamney, L.; Nigel Corlett, E. RULA: A survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Appl. Ergon. 1993, 24, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hignett, S.; McAtamney, L. Rapid entire body assessment (REBA). Appl. Ergon. 2000, 31, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scataglini, S.; Abts, E.; Van Bocxlaer, C.; Van den Bussche, M.; Meletani, S.; Truijen, S. Accuracy, Validity, and Reliability of Markerless Camera-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems versus Marker-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems in Gait Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, T.; Moslehian, A.S.; Peiffer, J.D.; Ullrich, J.; Gassert, R.; Lambercy, O.; Cotton, R.J.; Awai Easthope, C. Differentiable Biomechanics for Markerless Motion Capture in Upper Limb Stroke Rehabilitation: A Comparison with Optical Motion Capture. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.14992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, N.; Sakura, T.; Ueda, K.; Omura, L.; Kimura, A.; Iino, Y.; Fukashiro, S.; Yoshioka, S. Evaluation of 3D Markerless Motion Capture Accuracy Using OpenPose with Multiple Video Cameras. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avogaro, A.; Cunico, F.; Rosenhahn, B.; Setti, F. Markerless human pose estimation for biomedical applications: A survey. Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 5, 1153160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletani, S.; Scataglini, S.; Mandolini, M.; Scalise, L.; Truijen, S. Experimental Comparison between 4D Stereophotogrammetry and Inertial Measurement Unit Systems for Gait Spatiotemporal Parameters and Joint Kinematics. Sensors 2024, 24, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, M.; Lampen, E.; Auris, F.; Gaisbauer, F.; Rukzio, E. Applicability Evaluation of Kinect for EAWS Ergonomic Assessments. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, M.; Gamberi, M.; Pilati, F.; Regattieri, A. Automatic assessment of the ergonomic risk for manual manufacturing and assembly activities through optical motion capture technology. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, S.; Gül, M.; Al-Hussein, M.; El-Rich, M. 3D Visualization-Based Ergonomic Risk Assessment and Work Modification Framework and Its Validation for a Lifting Task. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04017093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, R.; Fisher-Gewirtzman, D. E-worker postural comfort in the third-workplace: An ergonomic design assessment. Work-A J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2020, 66, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrizi, R.; Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Metaxas, D.; Li, K. A computer vision based method for 3D posture estimation of symmetrical lifting. J. Biomech. 2018, 69, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, O.; Mertens, A.; Nitsch, V.; Brandl, C. Accuracy of a markerless motion capture system for postural ergonomic risk assessment in occupational practice. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 28, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, L.G.; Watkins, M.P. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein, J.D.; Huebner, A.; Wagle, J.P.; Cobian, E.R.; Cummings, J.; Hills, C.; McGinty, M.; Merritt, M.; Rosengarten, S.; Skinner, K.; et al. Reliability of Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Assessing Movement Screenings. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2024, 12, 23259671241234339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Z.; Lu, L.; Li, L.; Xu, X. A computer-vision method to estimate joint angles and L5/S1 moments during lifting tasks through a single camera. J. Biomech. 2021, 129, 110860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybnikár, F.; Kačerová, I.; Horejsi, P.; Michal, Š. Ergonomics Evaluation Using Motion Capture Technology—Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Scataglini, S.; Khafaga, N. A Systematic Review of the Accuracy, Validity, and Reliability of Marker-Less Versus Marker-Based 3D Motion Capture for Industrial Ergonomic Risk Analysis; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York: York, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate Analytics. EndNote (Version X20) [Software], Clarivate Analytics: North Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2021.

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Chiarotto, A.; Westerman, M.J.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Mokkink, L.B. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Boers, M.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias tool to assess the quality of studies on reliability or measurement error of outcome measurement instruments: A Delphi study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgers, J.S.; van Everdingen, J.J. Evidence-based guideline development in the Netherlands: The EBRO platform. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2004, 148, 2057–2059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abobakr, A.; Nahavandi, D.; Hossny, M.; Iskander, J.; Attia, M.; Nahavandi, S.; Smets, M. RGB-D ergonomic assessment system of adopted working postures. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 80, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldo, M.; De Marchi, M.; Martini, E.; Aldegheri, S.; Quaglia, D.; Fummi, F.; Bombieri, N. Real-time multi-camera 3D human pose estimation at the edge for industrial applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Mei, Q.; Li, X. 3D pose estimation dataset and deep learning-based ergonomic risk assessment in construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Skalli, W.; Siadat, A.; Gajny, L. Société de Biomécanique young investigator award 2023: Estimation of intersegmental load at L5-S1 during lifting/lowering tasks using force plate free markerless motion capture. J. Biomech. 2024, 177, 112422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chang, C. Simple method integrating OpenPose and RGB-D camera for identifying 3D body landmark locations in various postures. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2022, 91, 103354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manghisi, V.M.; Uva, A.E.; Fiorentino, M.; Bevilacqua, V.; Trotta, G.F.; Monno, G. Real time RULA assessment using Kinect v2 sensor. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 65, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrizi, R.; Peng, X.; Tang, Z.; Xu, X.; Metaxas, D.; Li, K. Toward Marker-free 3D Pose Estimation in Lifting: A Deep Multi-view Solution. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018), Xi’an, China, 15–19 May 2018; pp. 485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Patrizi, A.; Pennestri, E.; Valentini, P. Comparison between low-cost marker-less and high-end marker-based motion capture systems for the computer-aided assessment of working ergonomics. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantard, P.; Muller, A.; Pontonnier, C.; Dumont, G.; Shum, H.; Multon, F. Inverse dynamics based on occlusion-resistant Kinect data: Is it usable for ergonomics? Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2017, 61, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantard, P.; Shum, H.P.; Le Pierres, A.S.; Multon, F. Validation of an ergonomic assessment method using Kinect data in real workplace conditions. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 65, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Alwasel, A.; Lee, S.; Abdel-Rahman, E.; Haas, C. A comparative study of in-field motion capture approaches for body kinematics measurement in construction. Robotica 2019, 37, 928–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Crombrugge, I.; Sels, S.; Ribbens, B.; Steenackers, G.; Penne, R.; Vanlanduit, S. Accuracy Assessment of Joint Angles Estimated from 2D and 3D Camera Measurements. Sensors 2022, 22, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Zhang, Z.; McKeague, S.; Yang, G. Multi-person vision-based head detector for markerless human motion capture. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Body Sensor Networks, Cambridge, MA, USA, 6–9 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonakdar, A.; Riahi, N.; Shakourisalim, M.; Miller, L.; Tavakoli, M.; Rouhani, H.; Golabchi, A. Validation of markerless vision-based motion capture for ergonomics risk assessment. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2025, 107, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojelade, A.; Rajabi, M.S.; Kim, S.; Nussbaum, M.A. A data-driven approach to classifying manual material handling tasks using markerless motion capture and recurrent neural networks. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2025, 107, 103755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyer, S.L.; Evans, M.; Cosker, D.P.; Salo, A.I.T. A Review of the Evolution of Vision-Based Motion Analysis and the Integration of Advanced Computer Vision Methods Towards Developing a Markerless System. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).