Ca2Lib: Simple and Accurate LiDAR-RGB Calibration Using Small Common Markers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- A formulation for joint nonlinear optimization that couples relative rotation and translation using a plane-to-plane metric;

- An extensible framework that decouples optimization from target detection and currently supports checkerboard and ChARuCO patterns of typical A3–A4 sizes, which are easily obtainable from commercial printers;

- The possibility to handle different camera models and distortion;

- An open-source implementation.

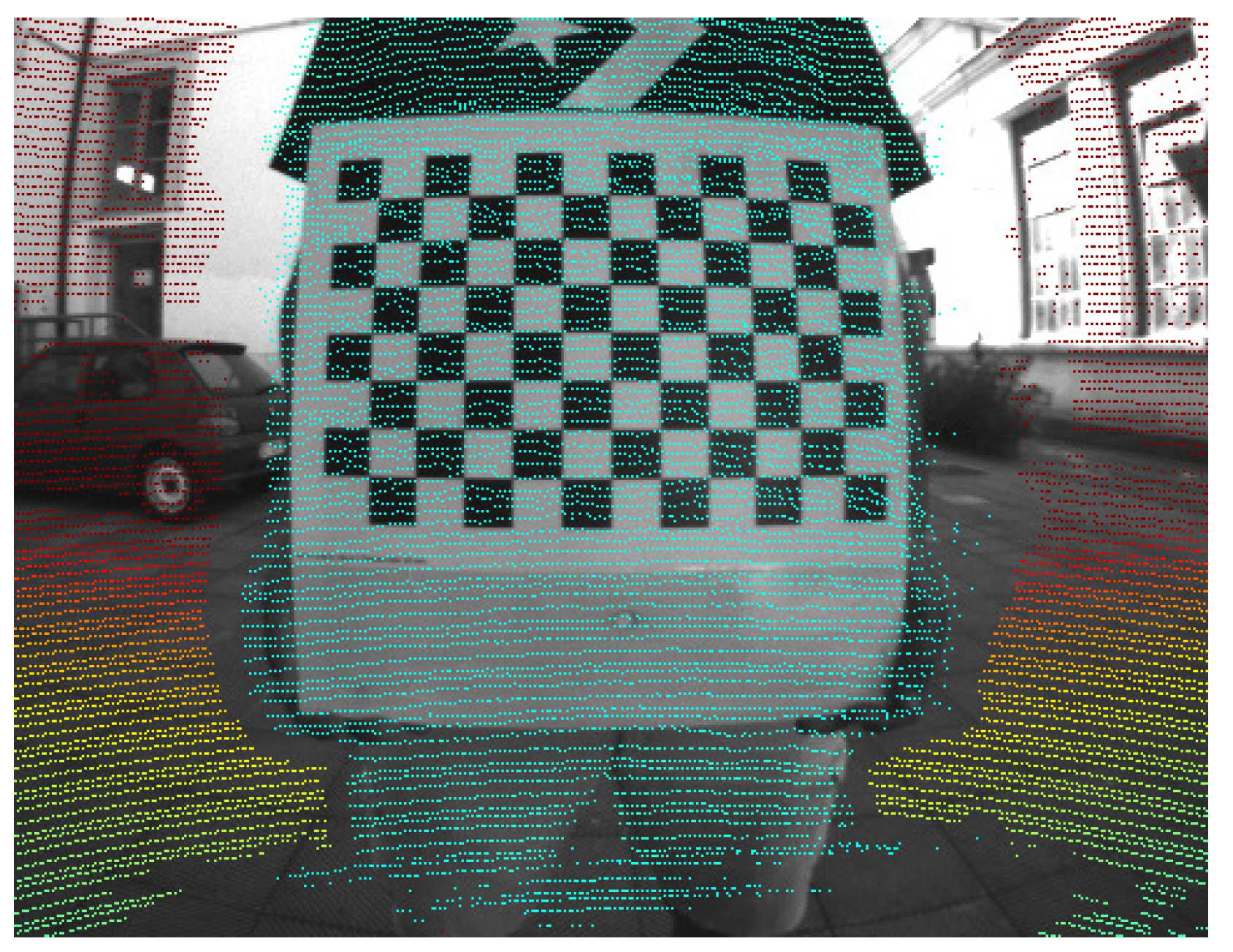

3. Our Approach

4. Experimental Evaluation

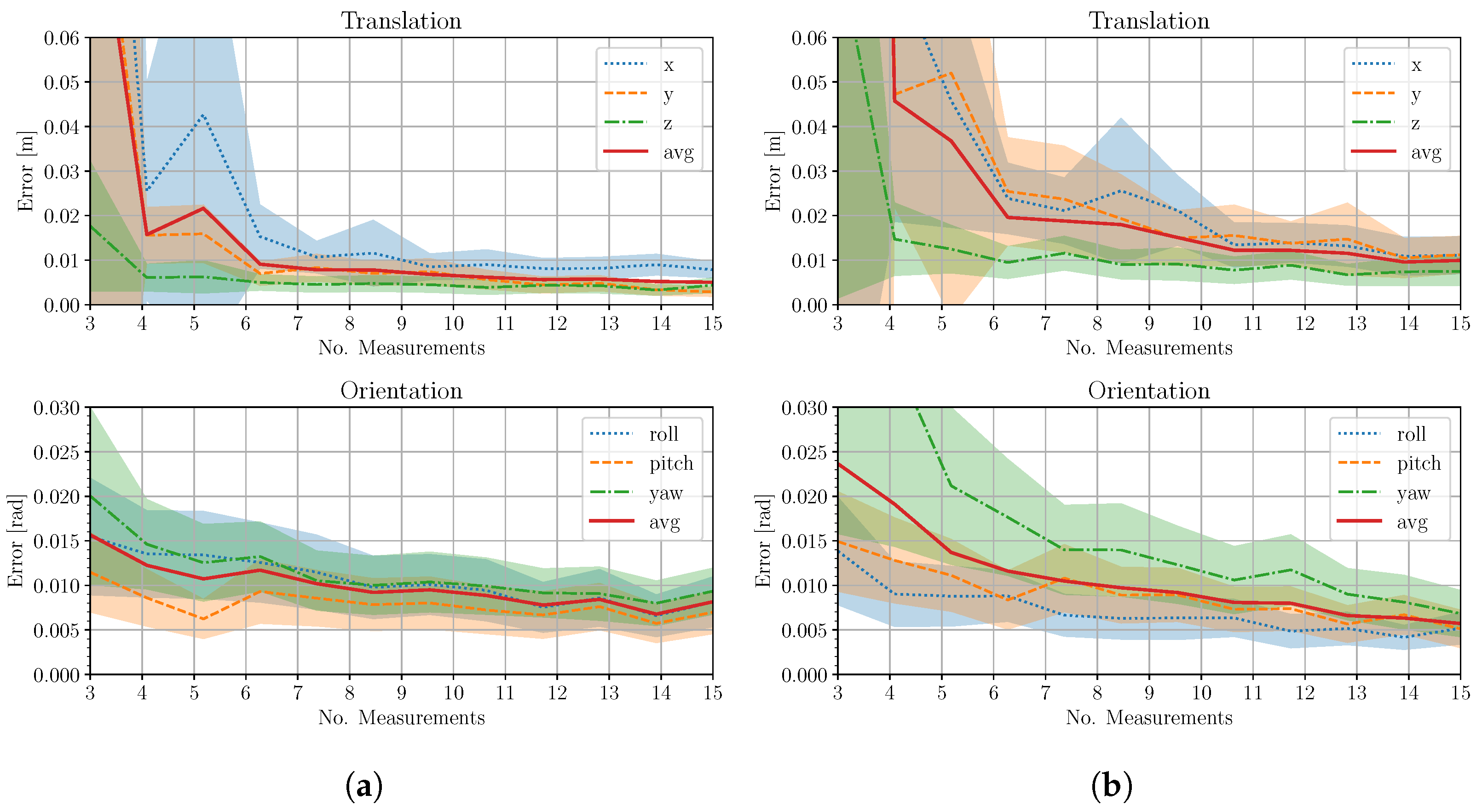

4.1. Synthetic Case

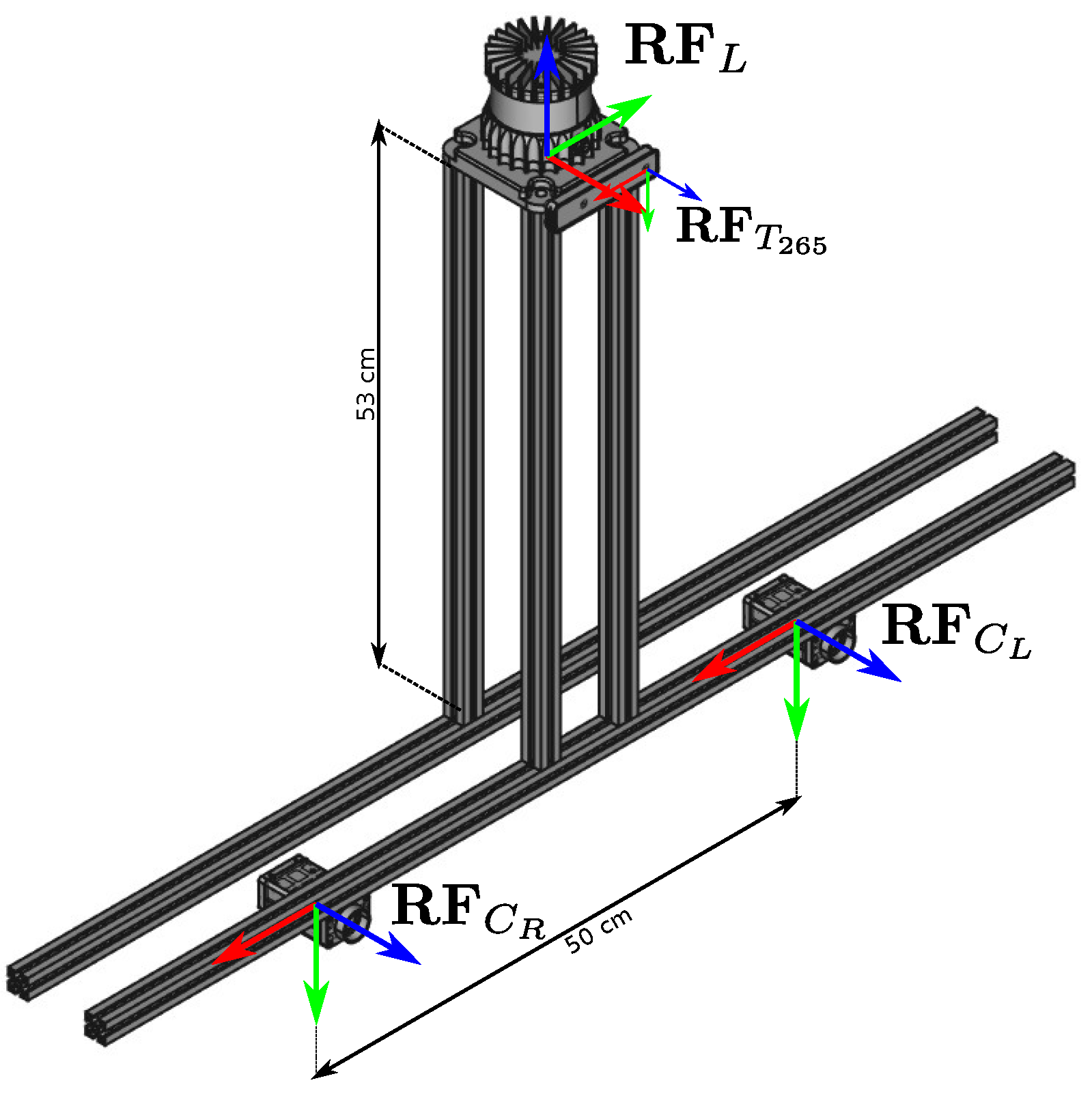

4.2. Real Case

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, T.Y.; Agrawal, P.; Chen, A.; Hong, B.W.; Wong, A. Monitored Distillation for Positive Congruent Depth Completion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.16034. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.; Soatto, S. Unsupervised Depth Completion with Calibrated Backprojection Layers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 12747–12756. [Google Scholar]

- Kam, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Lee, S. CostDCNet: Cost Volume Based Depth Completion for a Single RGB-D Image. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Proceedings, Part II. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Joo, K.; Hu, Z.; Liu, C.K.; Kweon, I.S. Non-Local Spatial Propagation Network for Depth Completion. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giammarino, L.; Giacomini, E.; Brizi, L.; Salem, O.; Grisetti, G. Photometric LiDAR and RGB-D Bundle Adjustment. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 4362–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradski, G. The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobb’s J. Softw. Tools 2000, 25, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth, J.; Kittler, J. The Adaptive Hough Transform. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1987, PAMI-9, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Jurado, S.; Muñoz-Salinas, R.; Madrid-Cuevas, F.; Marín-Jiménez, M. Automatic generation and detection of highly reliable fiducial markers under occlusion. Pattern Recognit. 2014, 47, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.; McBride, J.R.; Savarese, S.; Eustice, R.M. Automatic extrinsic calibration of vision and LiDAR by maximizing mutual information. J. Field Robot. 2015, 32, 696–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.H.; Jeong, H.W.; Choi, K.S. Targetless multiple camera-LiDAR extrinsic calibration using object pose estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 13377–13383. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Jiang, G.; Xu, A. LiDAR-Camera Calibration Using Line Correspondences. Sensors 2020, 20, 6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Wang, B.; Dou, Z.; Ye, D.; Wang, S. LCCNet: LiDAR and camera self-calibration using cost volume network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 2894–2901. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Wei, Z.; Huang, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, B. Automatic Targetless Calibration for LiDAR and Camera Based on Instance Segmentation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 8, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Yun, S.; Won, C.S.; Cho, K.; Um, K.; Sim, S. Calibration between Color Camera and 3D LIDAR Instruments with a Polygonal Planar Board. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 14, 5333–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusztai, Z.; Hajder, L. Accurate Calibration of LiDAR-Camera Systems Using Ordinary Boxes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, Z.; Eichhardt, I.; Hajder, L. Accurate Calibration of Multi-LiDAR-Multi-Camera Systems. Sensors 2018, 18, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Kaess, M. Automatic Extrinsic Calibration of a Camera and a 3D LiDAR Using Line and Plane Correspondences. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 5562–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E. AprilTag: A robust and flexible visual fiducial system. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 3400–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikopoulos, L.; Papanagnou, A.; Venianakis, A.; Kalisperakis, I.; Stentoumis, C. An Effective Camera-to-Lidar Spatiotemporal Calibration Based on a Simple Calibration Target. Sensors 2022, 22, 5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, T.; Pusztai, Z.; Hajder, L. Automatic LiDAR-Camera Calibration of Extrinsic Parameters Using a Spherical Target. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics & Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 8580–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, J.; Guindel, C.; de la Escalera, A.; García, F. Automatic Extrinsic Calibration Method for LiDAR and Camera Sensor Setups. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. (ITS) 2022, 23, 17677–17689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, F.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, C.; Wang, X. Accurate and Automatic Extrinsic Calibration for a Monocular Camera and Heterogenous 3D LiDARs. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 16472–16480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhao, L. High-Precision External Parameter Calibration Method for Camera and Lidar Based on a Calibration Device. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 18750–18760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singandhupe, A.; La, H.M.; Ha, Q.P. Single Frame Lidar-Camera Calibration Using Registration of 3D Planes. In Proceedings of the 2022 Sixth IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC), Naples, Italy, 5–7 December 2022; pp. 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, F.M.; Kottas, D.G.; Roumeliotis, S.I. 3D LIDAR–camera intrinsic and extrinsic calibration: Identifiability and analytical least-squares-based initialization. Int. J. Robot. Res. (IJRR) 2012, 31, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Park, S.Y. Extrinsic Calibration between Camera and LiDAR Sensors by Matching Multiple 3D Planes. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, N.; Howard, A. Design and use paradigms for gazebo, an open-source multi-robot simulator. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Sendai, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; Volume 3, pp. 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Velodyne Lidar. Datasheet for Velodyne HDL-64E S2; Velodyne: Morgan Hill, CA, USA; Available online: https://hypertech.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/HDL-64E-Data-Sheet.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Teledyne FLIR LLC. Blackfly S. Available online: https://www.flir.it/products/blackfly-s-usb3/?vertical=machine+vision&segment=iis (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Ouster Inc. High-Resolution OS0 LiDAR Sensor. Available online: https://ouster.com/products/hardware/os0-lidar-sensor (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Allied Vision Technologies. Modular Machine Vision Camera with GigE Vision Interface. Available online: https://www.alliedvision.com/en/camera-selector/detail/manta/g-145/ (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Intel Corporation. Datasheet for Realsense T265. Available online: https://dev.intelrealsense.com/docs/tracking-camera-t265-datasheet (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Katz, S.; Tal, A.; Basri, R. Direct Visibility of Point Sets. ACM Trans. Graph. 2007, 26, 24–es. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannala, J.; Brandt, S. A generic camera model and calibration method for conventional, wide-angle, and fish-eye lenses. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2006, 28, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | Mean | Stdev | Mean | Stdev | Mean | Stdev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 41.761 | 104.362 | 20.790 | 25.124 | 57.849 | 112.365 |

| 4 | 10.872 | 17.941 | 12.206 | 12.363 | 14.940 | 11.681 |

| 5 | 6.492 | 7.997 | 8.350 | 9.076 | 9.115 | 5.675 |

| 10 | 4.591 | 3.458 | 5.759 | 4.974 | 5.849 | 1.989 |

| 20 | 2.575 | 1.981 | 3.646 | 2.564 | 4.123 | 1.139 |

| 30 | 2.673 | 1.263 | 2.867 | 1.659 | 3.735 | 0.878 |

| 39 | 2.091 | 0.883 | 2.666 | 1.206 | 3.261 | 0.413 |

| Method | (cm) | ( rad) |

|---|---|---|

| Beltrán et al. [22] | 0.82 | 0.24 |

| Kim et al. [27] | 10.2 | 129.56 |

| Ours | 0.11 | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giacomini, E.; Brizi, L.; Di Giammarino, L.; Salem, O.; Perugini, P.; Grisetti, G. Ca2Lib: Simple and Accurate LiDAR-RGB Calibration Using Small Common Markers. Sensors 2024, 24, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24030956

Giacomini E, Brizi L, Di Giammarino L, Salem O, Perugini P, Grisetti G. Ca2Lib: Simple and Accurate LiDAR-RGB Calibration Using Small Common Markers. Sensors. 2024; 24(3):956. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24030956

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiacomini, Emanuele, Leonardo Brizi, Luca Di Giammarino, Omar Salem, Patrizio Perugini, and Giorgio Grisetti. 2024. "Ca2Lib: Simple and Accurate LiDAR-RGB Calibration Using Small Common Markers" Sensors 24, no. 3: 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24030956

APA StyleGiacomini, E., Brizi, L., Di Giammarino, L., Salem, O., Perugini, P., & Grisetti, G. (2024). Ca2Lib: Simple and Accurate LiDAR-RGB Calibration Using Small Common Markers. Sensors, 24(3), 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24030956