Abstract

A chitosan-based Cu2+ fluorescent probe was designed and synthesized independently using the C-2-amino group of chitosan with 1, 8-naphthalimide derivatives. A series of experiments were conducted to characterize the optical properties of the grafted probe. The fluorescence quenching effect was investigated based on the interactions between the probe and common metals. It was found that the proposed probe displayed selective interaction with Cu2+ over other metal ions and anions, reaching equilibrium within 5 min.

1. Introduction

Heavy metal ions are important environmental pollutants, primarily caused by human activities. The disruption caused by heavy metal ions can lead to their accumulation and even transmission in plants and animals, from lower to higher levels in the food chain, resulting in an extreme ecotoxicological impact, particularly on humans [1,2,3]. Cu2+ is a significant environmental pollutant and a harmful element in biological systems under overload conditions, which may lead to neurodegenerative disorders due to its likely involvement in the formation of reactive oxygen species [4,5,6]. The detection of Cu2+ in vitro or in vivo consistently represents an active area of research.

Various traditional analytical methods exist, including AAS (atom absorption spectrometry), ICP-ES (inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry) and ICP-MS (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry), etc. It is well known that these technologies offer good intelligent automation and limits of detection, but are very expensive and do not easily analyze on site [7,8,9]. Fluorescence probes have become a promising strategy because of their simplicity, non-destructive characteristics and structural modification to various conditions, etc. [10,11,12], which can translate molecular recognition information into tangible fluorescence signals by connecting a specific group to a fluorophore through organic methods. Currently, the development of Cu2+-specific fluorescent probes has been extensively explored [13,14,15]. Even though many innovative achievements have been made to realize Cu2+-related detection, most of them restricted their applications due to a long equilibrium time, lack of selectivity or poor sensitivity [16,17,18]. Therefore, the development of new technologies is urgently needed to address these issues to meet a wider range of demands. In recent years, researchers have explored a novel approach to design and prepare sensing materials by modifying chitosan with fluorescence dyes. These fluorescent materials have been applied to recognize heavy metal ions and have shown high selectivity and sensitivity.

Chitosan, the only cationic natural polysaccharide found in nature so far, has been widely used in cosmetics, the food industry, medical supplies and bioengineering, etc. [19,20,21]. Firstly, chitosan is a natural polymer with non-toxic, hydrophilic properties, biodegradability, and good renewability. Secondly, the hydroxyl and amino groups within chitosan molecules exhibit strong activity, making them easily amenable to chemical grafting and modification. Additionally, the presence of amino and hydroxyl groups enables chitosan molecules to form intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, resulting in a three-dimensional complex network structure capable of chelating heavy metal ions. Lastly, the attachment of multiple dye molecules onto a single chitosan molecule exhibits an optical additive effect during tissue binding and imaging, which significantly enhances the sensitivity and reduces the usage of probe. These unique properties render chitosan as an ideal carrier for functional fluorescent probes. In recent years, the amino group has been identified as the key factor affecting the activity of chitosan in the construction of fluorescent probes. Pournaki constructed a fluorescent probe through the esterylamolysis reaction between C-2 amino of chitosan and benzopyran derivatives to realize the identification of Fe3+ under acidic conditions [22]. Men et al. produced a Schiff base using the chitosan C-2-amino group with rhodamine glyoxal derivatives, which was successfully applied to recognize and adsorb Hg2+ in water [23]. The aforementioned studies validated the potential application of chitosan-based multifunctional materials in metal ion analysis.

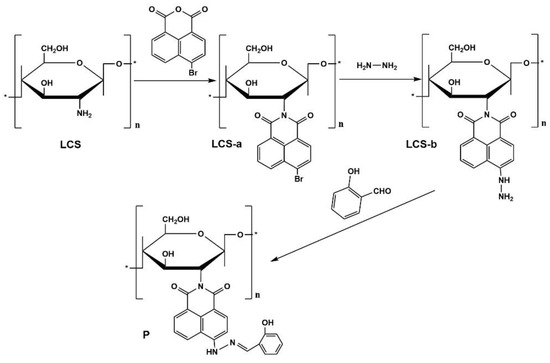

Herein, we presented a novel fluorescent material obtained through the modification of chitosan with naphthalimide dye. We anticipated that this fluorescent material could serve as a probe for the analysis of Cu2+ in environmental samples through fluorimetric or colorimetric methods. The synthetic scheme employed for chitosan-based fluorescent materials is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Synthetic scheme for compound P, “*” represents the repeated units.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments and Reagents

Fluorescence spectra were determined with an F-4600 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet Magna-IR 750 spectrometer equipped with a Nic-Plan Microscope (Nicolet, Madison, WI, USA). 1H NMR spectra were performed by a Bruker AV 400 instrument with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard and DMSO-d6 as a deuterium generation reagent (Bruker, Karlsruche, Germany). Absorption spectra were measured with a U-2910 spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). All pH measurements were made with a Model PHS-3C meter (Jinpeng, Shanghai, China).

All reagents were analytically pure and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) without special treatment before use. The metal ion salts used were NaCl, KCl, CaCl2·2H2O, MgCl2·6H2O, CdCl2, CrCl3·6H2O, HgCl2, CuCl2·2H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, AgNO3 and AlCl3·6H2O; and anion species were from various salts such as NaHCO3, NaNO3, Na2CO3, NaF, Na2SO4, Na2C2O4 and Na2HPO4.

2.2. Synthesis of LCS-a

First, 1.0013 g of chitosan (LCS) was dissolved in 200 mL of anhydrous ethanol. Subsequently, 3.0185 g of 4-bromo-1, 8-naphthalene anhydride was added to the reaction flask. The mixture was refluxed for 8 h. The resulting product was then promptly filtered and washed with hot ethanol. The precipitate of LCS-a obtained was subjected to extraction using Sechelt’s extractor with ethanol for 12 h. IR (KBr): 3425.23 cm−1, 1779.22 cm−1, 1732.91 cm−1, 1588.16 cm−1, 1570.09 cm−1, 1299.06 cm−1, 1224.03 cm−1, 1132.76 cm−1, 1022.02 cm−1, 773.77 cm−1.

2.3. Synthesis of LCS-b

First, 0.5000 g of newly prepared LCS-a, 20 mL of anhydrous ethanol and 8 mL of hydrazine hydrate (85%) were placed in a round-bottom flask. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6 h and cooled to room temperature. Then, the red brown precipitate of LCS-b was extracted by Sechelt’s extractor with ethanol for at least 12 h. IR (KBr): 3441.09 cm−1, 3329.42 cm−1, 1638.30 cm−1, 1581.41 cm−1, 1537.33 cm−1, 1396.95 cm−1, 1366.06 cm−1, 1254.23 cm−1, 974.48 cm−1, 768.30 cm−1.

2.4. Synthesis of P

First, 0.2500 g of LCS-b and 40 mL of anhydrous ethanol were put into a three-neck flask. Then, 1.1 mL of salicylaldehyde was added dropwise. After reflux for 7 h, it was cooled to room temperature and filtered to obtain the crude product, which was further purified using a Soxhlet extractor with anhydrous ethanol for 4 h to obtain P. IR (KBr): 3434.04 cm−1, 3278.44 cm−1, 1666.57 cm−1, 1583.60 cm−1, 1382.21 cm−1, 1336.13 cm−1, 1290.53 cm−1, 1239.53 cm−1, 1129.35 cm−1, 757.91 cm−1.

2.5. Preparation of the Test Solution

The solutions of various testing metal ion species were prepared from NaCl, KCl, CaCl2·2H2O, MgCl2·6H2O, CdCl2, CrCl3·6H2O, HgCl2, CuCl2·2H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, AgNO3 and AlCl3·6H2O; and anion species were from various salts such as NaHCO3, NaNO3, Na2CO3, NaF, Na2SO4, Na2C2O4 and Na2HPO4 to obtain 1 mM stock solution in the twice-distilled water. A solution containing 2000 ppm of P was prepared in DMSO.

2.6. UV–Vis and Fluorescence Titration

Test solutions were prepared by placing 50 μL of the P stock solution (2000 ppm) into a test tube, adding an appropriate aliquot of individual ions stock solution (1 mM), and then diluting the solution to 5 mL with aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9). The excitation wavelength was recorded at 430 nm. The test medium was in the aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9).

2.7. The Calculation of the Combined Constant

The binding constants for the formation of the P-Cu2+ complex were evaluated using the Benesi–Hildebrand plot [24].

F0 is the fluorescence intensity of P without Cu2+, F is the fluorescence intensity of P obtained with Cu2+, Fmax is the fluorescence intensity of P in the presence of an excess amount of Cu2+ and K is the binding constant (M−1) determined from the slope of the linear plot.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FTIR and 1H NMR Spectra of the LCS, LCS-a and LCS-b

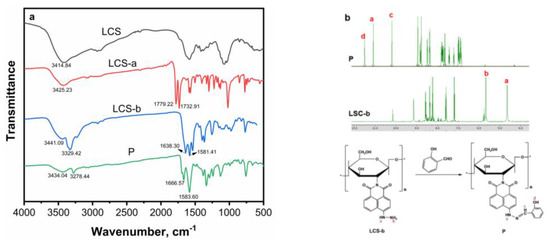

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to ascertain that the grafting of the naphthalimide derivative onto chitosan was successful. As illustrated in Figure 2a, the IR spectra of LCS, LCS-a, LCS-b and P were presented. Initially, LCS exhibited vibrations about ~3400 cm−1 corresponding to the hydroxyl groups. Subsequent to the reaction of chitosan with naphthalimide, the characteristic absorption peak of the carbonyl group emerged in the range of 1800–1700 cm−1, signifying the successful synthesis of LCS-a. Following the grafting of the hydrazyl group, LCS-b exhibited an absorption peak of the carbonyl group at 1600 cm−1, accompanied by increased conjugation, while the characteristic absorption peak of -NH2 appeared at 3300 cm−1. After the Schiff base condensation reaction between LCS-b and salicylaldehyde, the strong absorption peak at 1583 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching vibration of C=N and the skeleton vibration of the benzene ring, and the absorption peak of -NH2 disappeared. Crucially, a shift in the carbonyl stretching (i.e., 1666 cm−1) of the grafted chitosan was observed, which was attributed to the presence of hydrogen bonding, possibly between the carbonyl oxygen of naphthalimide and the available hydroxyl and unreacted amine groups of chitosan. These results collectively indicated the successful construction of P.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR pattern of LCS, LCS-a, LCS-b and P; (b) 1H NMR of LCS-b and P, “a–d” stand for H form -NH, -NH2, -N=CH- and -OH groups, respectively; “*” represents the repeated units.

In 1H NMR spectra of LSC-b (Figure S1) and P (Figure S2), the characteristic peak of -NH2 at 5.67 ppm disappeared after the reaction of LCS-b and salicylaldehyde. The peak of -NH shifted from a high field of 4.64 ppm to a low field of 11.10 ppm, while the characteristic peaks of -OH and -N=CH appeared at 11.52 and 10.20 ppm, respectively, which also confirmed the formation of P.

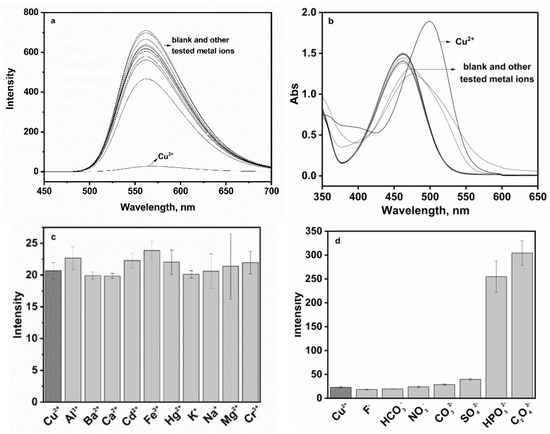

3.2. Application of P for the Detection of Cu2+

Fluorescent material P featured excellent optical property and displayed strong green fluorescence at 560 nm in 10% aqueous solution at pH 7.0 (Figure 3a). With 100 µM of Cu2+, the fluorescence intensity of P (20 ppm) was almost completely quenched, which could be ascribed to a PET mechanism and/or a paramagnetic effect of Cu2+ [25]. No significant spectral changes in P occurred in the presence of alkali or alkaline, earth metals or the first-row transition metals including Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, Ag+, Cr3+, Fe3+ and Al3+. The absorption spectra of P to Cu2+ were depicted in Figure 3b. P displayed an absorption band with a peak at 462 nm, which was attributed to the energy bond of n-π* and π-π* in the electron transition of naphthalimide. Upon addition of Cu2+, there was a noticeable spectral change accompanied by a red-shifted absorption peak at 499 nm. Furthermore, upon adding 1 equiv. of Cu2+ to the above other metal ions solution (100 μM), drastic quenching occurred, consistent with the addition of 1 equiv. of Cu2+ alone, indicating that Cu2+-specific responses were not affected by competitive metal ions (Figure 3c). The fluorescence responses of probe P to Cu2+ in the presence of various coexistent anions such as HCO3−, NO3−, CO32−, F−, SO42−, C2O42− and HPO42− were also investigated. However, it is worth noting that C2O42− and HPO42− caused some interference.

Figure 3.

(a) Selectivity of P (20 ppm) in the presence of common metal ions (100 µM) including Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, Ag+, Cr3+, Fe3+ and Al3+; (b) absorption spectra of P (20 ppm) for metal ions (100 µM); (c) fluorescence response of P (20 ppm) to Cu2+ (100 µM) in the presence of other metal ions (100 µM); (d) fluorescence response of P (20 ppm) to Cu2+ (100 µM) in the presence of anion ions including HCO3−, NO3−, CO32−, F−, SO42−, C2O42− and HPO42− (100 µM) in the aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9).

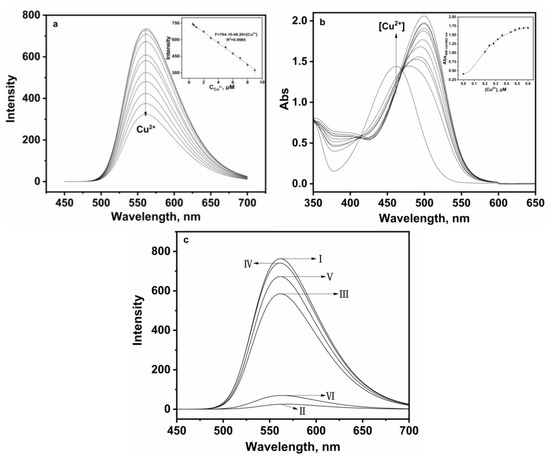

Under the same experimental conditions, the interaction of P and various Cu2+ concentrations were employed to explain the effect on the quenching. As shown in Figure 4a, the gradual increase in Cu2+ concentration resulted in a linear decrease in fluorescence intensity, and there was no obvious change in spectral shape. It was found that the quenched fluorescence intensity of P was directly proportional to the Cu2+ concentration, the emission intensity at 561 nm and Cu2+ concentration in the range of 0.5–9 µM, which were found linear with R2 = 0.998, indicating that P would be a highly efficient fluorescence probe for Cu2+; the association constant K was determined from the slope to be 1.9 × 105 M−1, which could be described by a Benesi–Hildebrand equation [24]. Meanwhile, the detection limit of P for Cu2+ was established at 0.027 µM under current experimental conditions (based on 3 s/k, s is the standard deviation of the measured intensity of the blank solution and k is the slope of the plot in the inset of Figure 4a), which demonstrated that probe P could be utilized for both qualitative and quantitative sensing of Cu2+, achieving a sensitivity threshold of 30 µM Cu2+ in drinking water according to the World Health Organization (WHO) standard [26]. As seen from Figure 4b, upon sequential addition of Cu2+, the absorption band centered at 499 appeared with increasing intensity, which induced a clear color change from pale yellow to orange; meanwhile, the band at 462 nm decreased gradually in intensity, with an isosbestic point at 413 nm. The ratio of absorbance at 499–462 nm increased linearly with the increase in Cu2+ concentration (inset of Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of P (20 ppm) in the presence of different amounts of Cu2+ (0.5–9 μM) in the aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9). Inset: Linear fluorescence intensity at 561 nm of P (20 ppm) upon addition of Cu2+ (0.5–9 μM); (b) absorption spectra of P (20 ppm) in the presence of different amounts of Cu2+ (0–0.6 μM) in the aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9). Inset: Absorbance ratio at 499 nm and 462 nm of P (20 ppm) upon addition of Cu2+ (0–0.6 μM); (c) the reversibility experiment: I. P (20 ppm), II. P (20 ppm) + Cu2+ (10 μM), III. P (20 ppm) + Cu2+ (10 μM) + EDTA (10 μM), IV. P (20 ppm) + Cu2+ (10 μM) + EDTA (100 μM), V. P (20 ppm) + Cu2+ (10 μM) + EDTA (100 μM) + Cu2+ (10 μM); VI. P (20 ppm) + Cu2+ (10 μM) + EDTA (100 μM) + Cu2+ (100 μM).

Moreover, the fluorescence signal was significantly enhanced by adding different concentrations of EDTA to the solution containing P and Cu2+ (Figure 4c III–IV), while the fluorescence intensity was again quenched when excessive Cu2+ was added (Figure 4c V–VI). The experiment proved that probe P had good reversibility, which will be helpful for recycling.

In addition, under the aforementioned optimal experimental conditions, we utilized the standard addition method for quantitative analysis and detection of Cu2+ in three types of commercially available bottled water. The results of the analysis are detailed in Table 1. The experimental data indicated a high recovery rate (100.3–118%) for the determination of Cu2+ in water samples using this method. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that fluorescence probe P can hold a significant practical application potential for the analysis and detection of Cu2+ in real-world samples. Meanwhile, a comparison of Cu2+-specific probes is presented in Table 2. Different probes derived from chitosan-based naphthalimide or naphthalimide displayed different characteristics, exhibiting fluorescence enhancement or quenching, which demonstrated a quick response [27,28,29], potential application value [27,30,31,32] and high sensitivity [27,29,31]. Meanwhile, various drawbacks could not be ignored, such as the organic solvent for dissolving [27,28,29,30,31,32,33], the long equilibrium time [31,32], narrow detection ranges [28], and low sensitivity [29,31]. Our probe P was a valuable probe with a fast equilibrium time, wide detection range, good reversibility, a visible light for excitation and emission. However, further optimization of probe structure is needed to improve water solubility and extend applications. Generally, P had some outstanding superiority to the other mentioned Cu2+-probes.

Table 1.

Determination of Cu2+ in sample water (n = 3).

Table 2.

Performance comparison of various fluorescent probes for Cu2+.

3.3. Reaction Mechanism Research

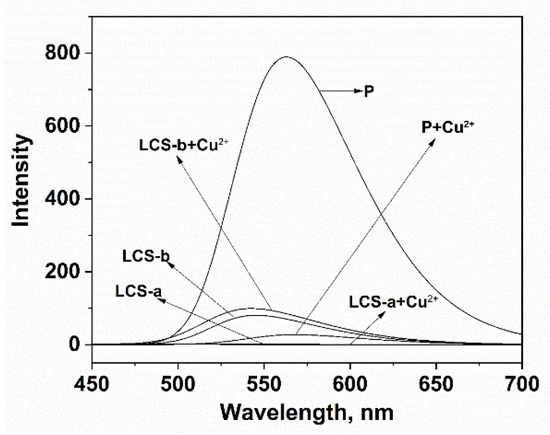

The probable complexation between P and Cu2+ was further verified through the selectivity of a series of controls as shown in Figure 5. The experimental results clearly displayed the interaction between each control compound and Cu2+. There was no significant fluorescence signal change after Cu2+ was added to the solution of LCS-a. The combination of LCS-b and Cu2+ only produced a weak fluorescence enhancement at 544 nm. However, when P combined with Cu2+, the fluorescence quenching phenomenon was obvious at 561 nm, explaining the selectivity of P in Cu2+ detection and recognition.

Figure 5.

Comparison of selectivity of LCS-a, LCS-b and P (20 ppm) for Cu2+ (100 µM) in the aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9).

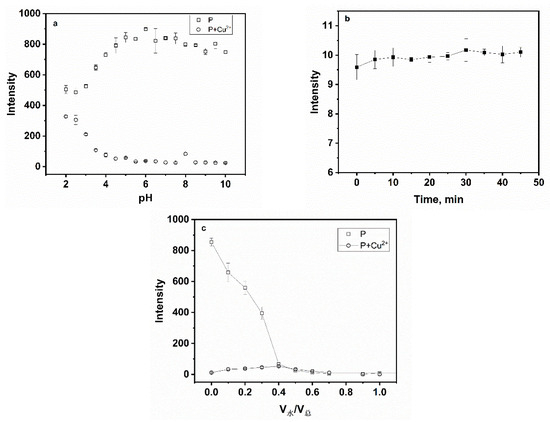

3.4. Experimental Condition Optimization

The effect of pH was first investigated to evaluate the sensing for Cu2+ as depicted in Figure 6a. When pH < 4.5, the fluorescence intensity of P at 561 nm increased gradually and a decrease in the fluorescence intensity followed the mixing of P with Cu2+. When pH > 4.5, the fluorescence intensity of P and the P-Cu2+ system tended to remain fairly static in the wide range of pH 5–10. Thereby, the pH control measurements revealed that P was utilized in weak acid, neutral and weakly alkaline environments, which was an advantage in later applications. To study the influence of time on the fluorescence intensity, freshly prepared samples were immediately tested, and then a 5 min interval was set, as seen in Figure 6b. The fluorescence signal was almost completely quenched within 5 min after Cu2+ was added to the solution of P, which indicated that the reaction between P and Cu2+ was almost instantaneous. Meanwhile, the effect of water content on fluorescence quenching was also studied. Figure 6c showed that with the increasing volume fraction of water, the fluorescence emission of P and P-Cu2+ can be strongly quenched. In order to further explore the effect between P and Cu2+, all measurements were carried out in aqueous-ethanol media (pH 7.0, 20 mM HEPES, v:v = 1:9).

Figure 6.

(a) Effect of pH on fluorescence spectra of P (20 ppm) and P (20 ppm) for Cu2+ (100 µM); (b) Effect of time on the recognition between Cu2+ (100 µM) and P (20 ppm); (c) effect of water content on fluorescence spectra of P (20 ppm) and P (20 ppm) for Cu2+ (100 µM).

4. Conclusions

In summary, we successfully constructed a chitosan-naphthalimide fluorescence probe that is capable of instantaneous selective detection of Cu2+. The result showed that the chitosan-based fluorescent probe possessed high selectivity and sensitivity for Cu2+ over other common metal ions, which confirmed that our idea was feasible. We believe that this design concept should serve as a reference to develop new chitosan-based probes for transition metal ions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/s24113425/s1, Figure S1: 1H NMR of LCS-b, Figure S2: 1H NMR of P.

Author Contributions

C.Y., methodology and original draft preparation; J.H., software and formal analysis; M.Y., resources; J.Z., supervision and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (No. ZDYF2022SHFZ076, No. ZDYF2022SHFZ307), the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (No. 820RC626, No. 821RC559) and the Colleges and Universities Scientific Research Projects of the Education Department of Hainan Province (NO. Hnky2023-26).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Han, T.; Yuan, Y.; Kang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. Ultrafast, sensitive and visual sensing of copper ions by a dual-fluorescent film based on quantum dots. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 14904–14912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.R.; Pichtel, J.; Hayat, S. Copper: Uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants and management of Cu-contaminated soil. Biometals 2021, 34, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.S.; Paul, K.; Luxami, V. A fluorescent probe with “AIE+ESIPT” characteristics for Cu2+ and F− ions estimation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 246, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, S.; Malkondu, S.; Kocyigit, O. A blue/red dual-emitting multi-responsive fluorescent probe for Fe3+, Cu2+ and cysteine based on isophorone-antharecene. Microchem. J. 2020, 157, 105075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, W. Synthesis of green-emitting carbon quantum dots with double carbon sources and their application as a fluorescent probe for selective detection of Cu2+ ions. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 2536–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Cao, D.; Meng, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Z.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, T.; Han, X.; Ma, W. A novel fluorescent chemosensor based on coumarin and quinolinyl-benzothiazole for sequential recognition of Cu2+ and PPi and its applicability in live cell imaging. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 230, 118022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Bing, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, G. A new “ON-OFF” fluorescent and colorimetric chemosensor based on 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivative for the detection of Cu2+ ions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 360, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, B.; Zhou, L.; Li, D.; Kong, L.; Uvdal, K.; Hu, Z. A reversible and highly selective two-photon fluorescent “on-off-on” probe for biological Cu2+ detection. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 2264–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, E. A highly selective “turn-on” fluorescent probe for detecting Cu2+ in two different sensing mechanisms. Dyes Pigments. 2019, 163, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, R.; Yi, F.; Liang, X.; Cheng, S.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y. Highly emissive multipurpose organoplatinum (II) metallacycles with contrasting mechanoresponsive features. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 2883–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, R.; Yuan, C.; Shao, T.; Wang, K.; Tan, H.; Sun, Y. Ligand-triggered platinum (II) metallacycle with mechanochromic and vapochromic responses. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 9387–9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, W.N.; Li, S.J.; Xu, Z.H.; Xu, Z.Q.; Fan, Y.C.; Zhao, X.L.; Liu, B.Z. An AIRE active schiff base bearing coumarin and pyrrole unit: Cu2+ detection in either solution or aggregation states. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 260, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Niu, Q.; Li, T.; Sun, T.; Chi, H. A fast, highly selective and sensitive colorimetric and fluorescent sensor for Cu2+ and its application in real water and food samples. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 213, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Kou, J.; Mei, H.; Gu, X.; Wang, M.; Xie, X.; Xu, K. A hemicyanine-based “turn-on” fluorescent probe for the selective detection of Cu2+ ions and imaging in living cells. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 4181–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Han, D.; Li, X.; Peng, M.; Zeng, X.; Jing, L.; Qin, D. A new Cu2+-selective fluorescent probe with six-membered spirocyclic hydrazide and its application in cell imaging. Dyes Pigments. 2019, 171, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wu, P.; Li, F.; Jin, L.; Lou, D. Visual colorimetric and fluorescence turn-on probe for Cu(II) ion based on coordination and catalyzed oxidative cyclization of ortho amino azobenzene. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 487, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Liang, Q.; Feng, R.; Lv, Z.; Cui, F.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Hong, L.; Sun, F. A pyrene-containing Schiff base fluorescent ratiometric probe for the detection of Cu2+ in aqueous solutions and in cells. J. Photoch. Photobio. 2020, 408, 113086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, S.I.; Mahata, G.; Pahari, P.; Pramanik, N.; Atta, A.K. A simple triazole-linked bispyrenyl-based xylofuranose derivative for selective and sensitive fluorometric detection of Cu2+. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 507, 119582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xing, R.; Liu, S.; Qin, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, H.; Li, P. Chitosan, hydroxypropyltrimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan and sulfated chitosan nanoparticles as adjuvants for inactivated newcastle disease vaccine. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020, 229, 115423–115431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romany, A.; Payne, G.F.; Shen, J.A. Effect of acetylation on the nanofibril formation of chitosan from all-atom de novo self-assembly simulations. Molecules. 2024, 29, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Araby, A.; Janati, W.; Ullah, R.; Ercisli, S.; Errachidi, F. Chitosan, chitosan derivatives, and chitosan-based nanocomposites: Eco-friendly materials for advanced applications (a review). Front. Chem. 2024, 11, 1327426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pournaki, M.; Fallah, A.; Gulcan, H.O.; Gazi, M. A novel chitosan based fluorescence chemosensor for selective detection of Fe (III) ion in acetic aqueous medium. Mater. Technol. 2021, 36, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; He, C.; Su, W.; Zhang, X.; Duan, C. A new rhodamine-chitosan fluorescent material for the selective detection of Hg2+ in living cells and efficient adsorption of Hg2+ in natural water. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 174, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Caceres, M.I.; Agbaria, R.A.; Warner, I.M. Fluorescence of metal-ligand complexes of monoand di-substituted naphthalene derivatives. J. Fluoresc. 2005, 15, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.C.; Yang, R.; He, H.; Jiang, Y.B. A highly selective charge transfer fluoroionophore for Cu2+. Chem. Commun. 2006, 1, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 3rd ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Nie, J.; Wu, L.; Chen, W.; Qi, S.; Xu, H.; Du, J.; Shan, Y.; Yang, Q. A novel hydrophilic fluorescent probe for Cu2+ detection and imaging in HeLa cells. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 10264–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pršir, K.; Matić, M.; Grbić, M.; Mohr, G.J.; Krištafor, S.; Steinberg, I.M. Naphthalimide-piperazine derivatives as multifunctional “on” and “off” fluorescent switches for pH, Hg2+ and Cu2+ ions. Molecules 2023, 28, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, S.; Sun, W.; Chen, R.; Yuan, Z.; Cheng, X. Fluorescent dialdehyde-BODIPY chitosan hydrogel and its highly sensing ability to Cu2+ ion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, K.; Wu, H. A selective fluorescence probe for copper (II) ion in aqueous solution based on a 1, 8-naphthalimide Schiff base derivative. Z. Naturforsch. B. 2019, 74, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qin, W.; Hu, Q.; Tang, B.Z. Fluorescent detection of Cu(II) by chitosan-based AIE bioconjugate. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 35, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. A naphthalimide functionalized chitosan-based fluorescent probe for specific detection and efficient adsorption of Cu2+. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Yu, B.; Yu, C. A pyridine-containing Cu2+-selective probe based on naphthalimide derivative. Sensors 2014, 14, 24146–24155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).