Proposal for a New Differential High-Sensitivity Refractometer for the Simultaneous Measurement of Two Refractive Indices and Their Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

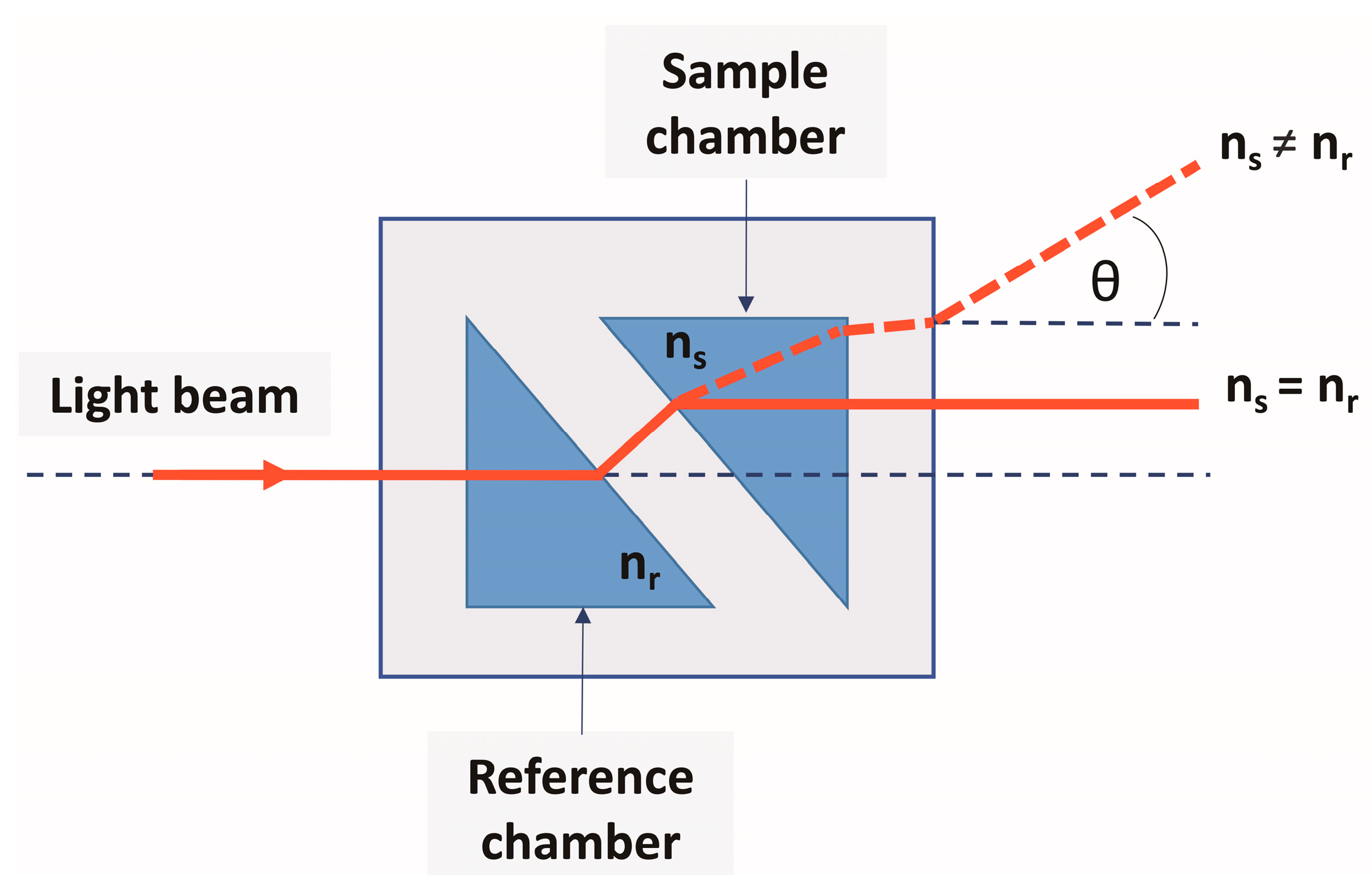

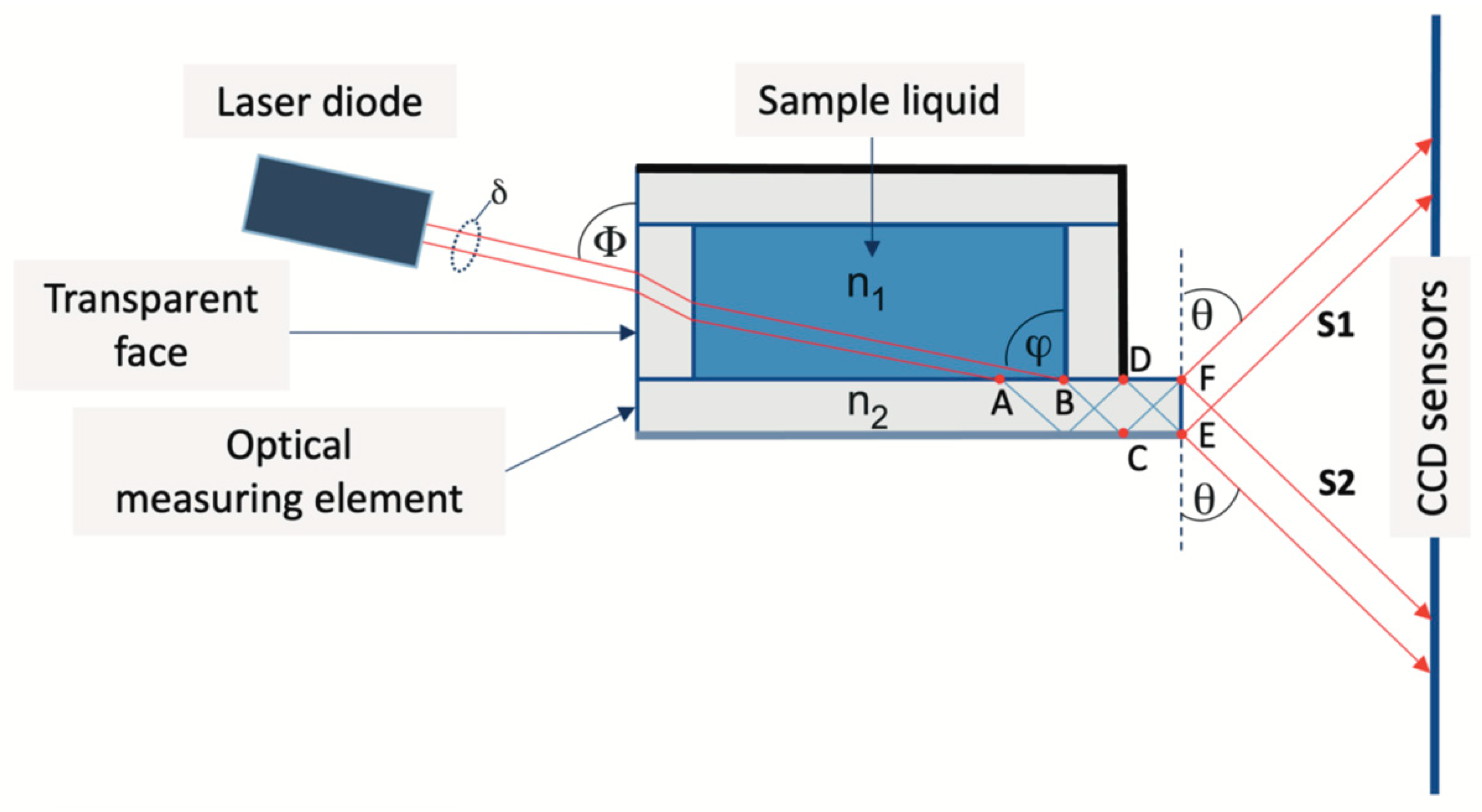

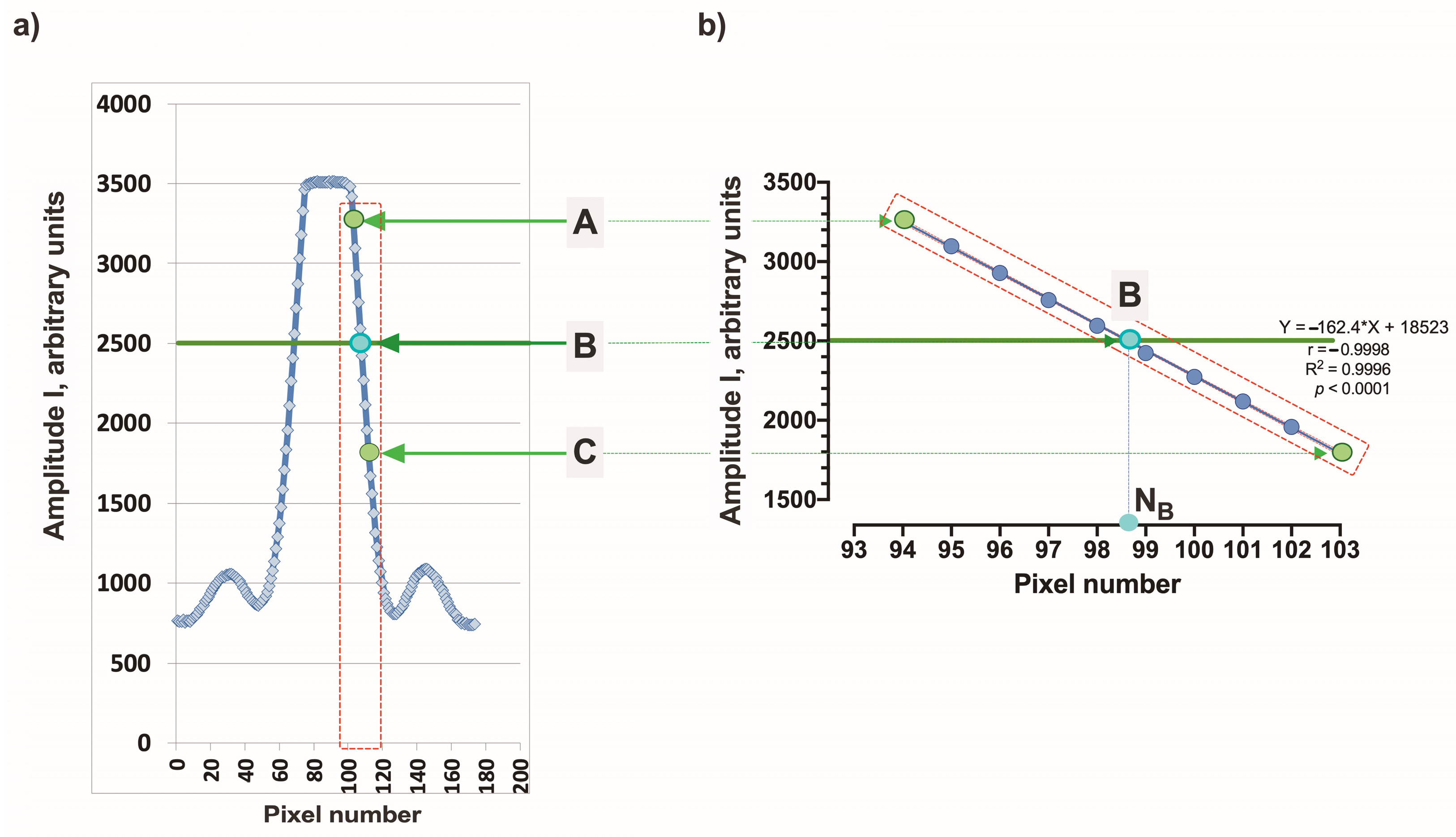

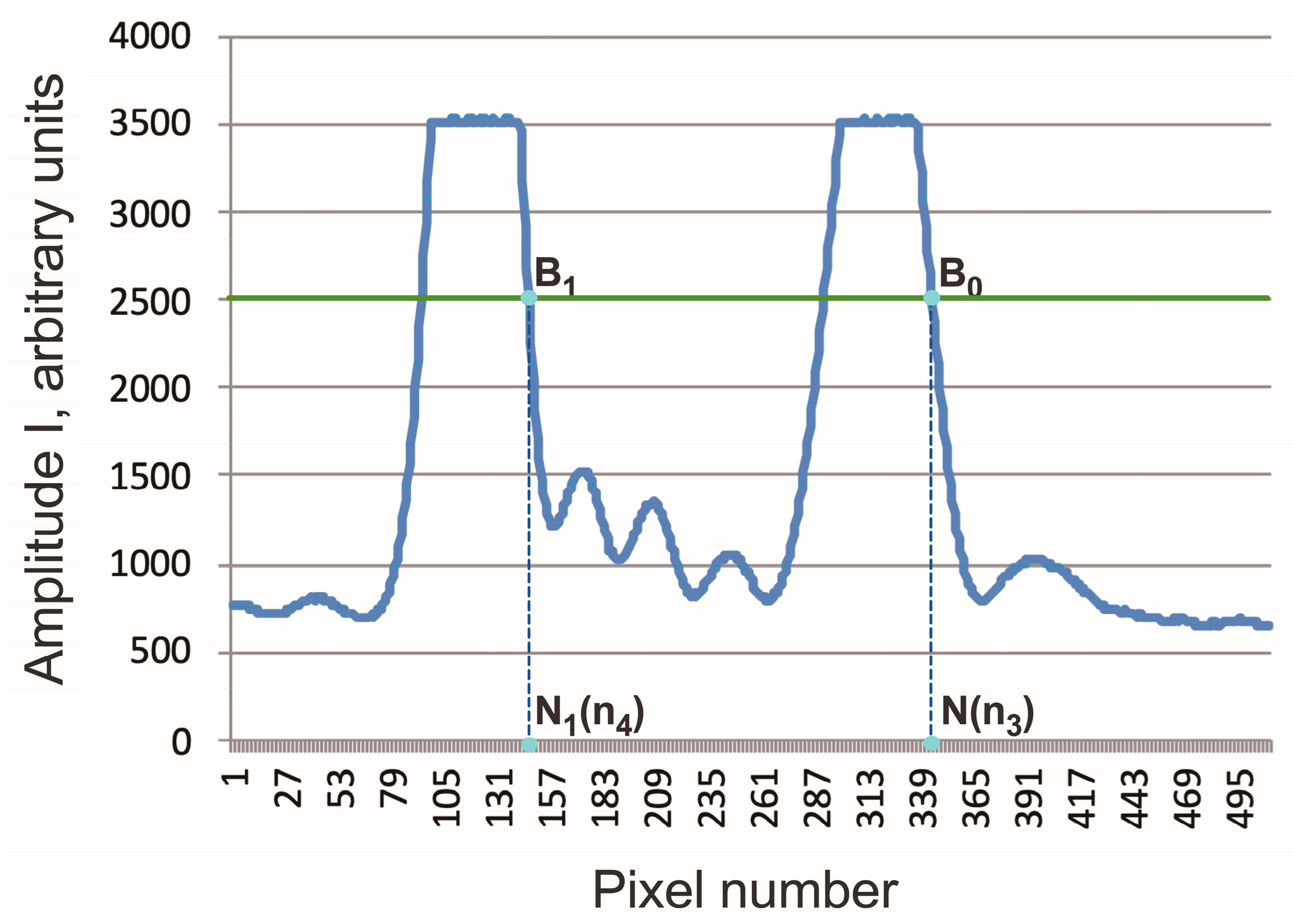

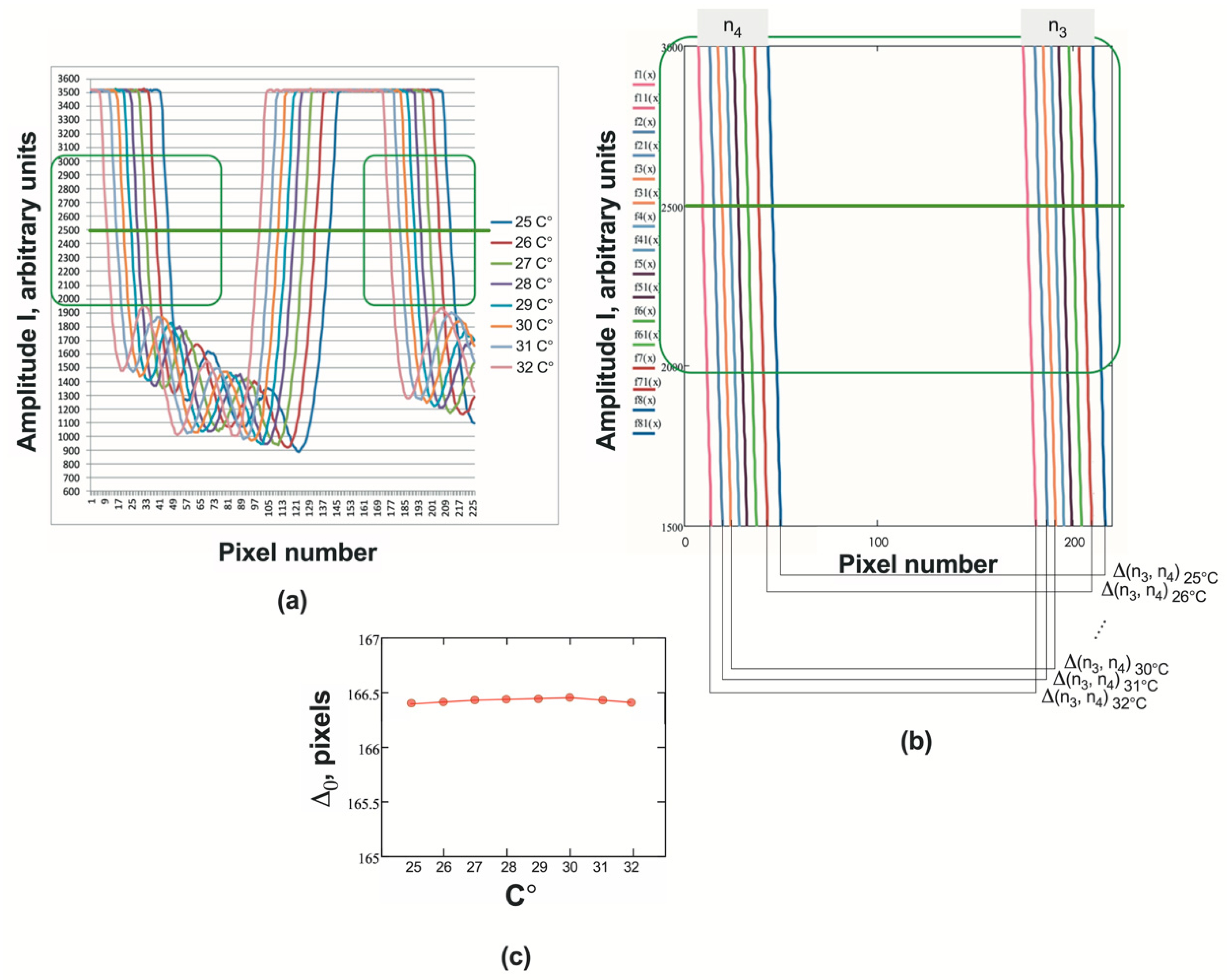

2. Principles of the RI Measurement

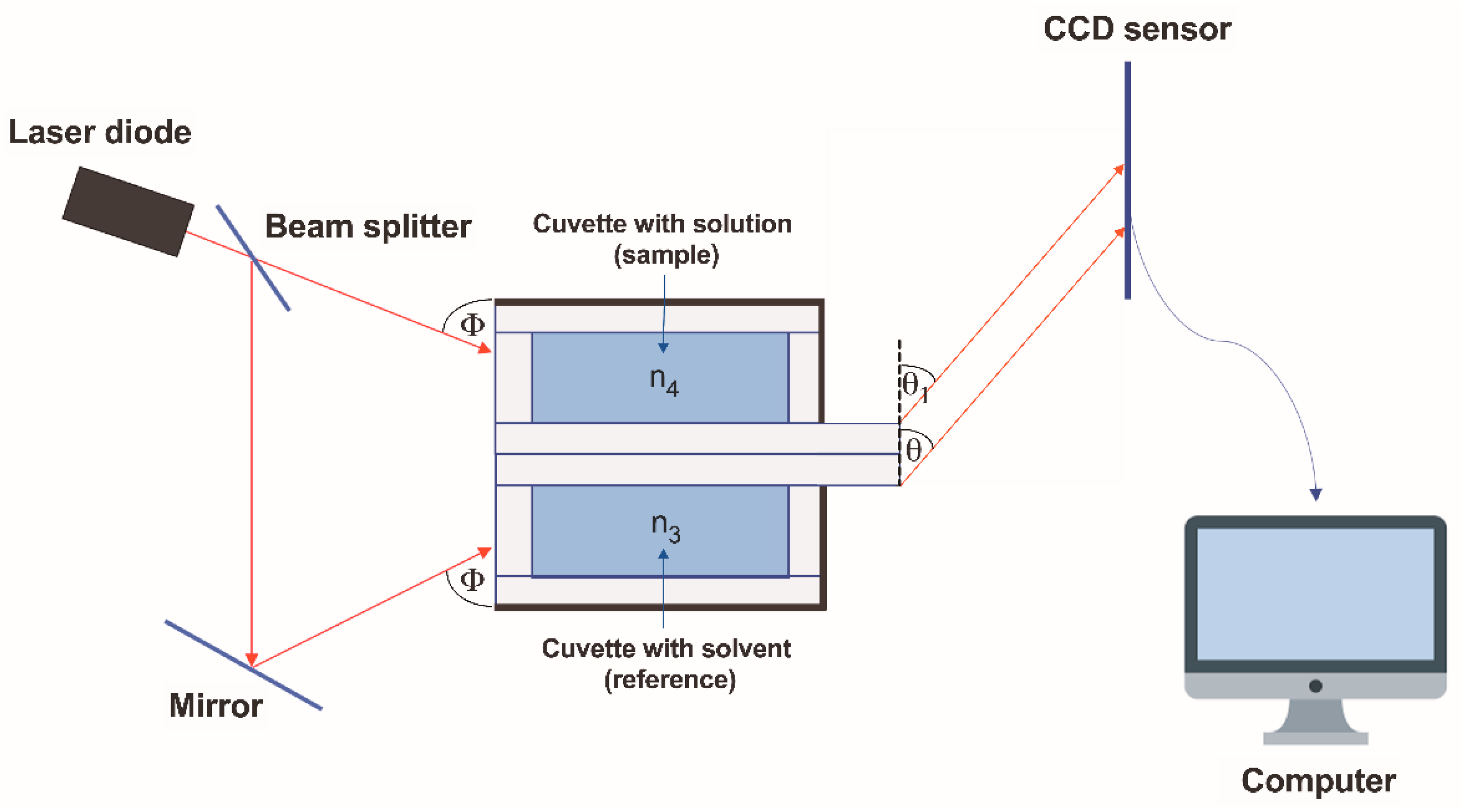

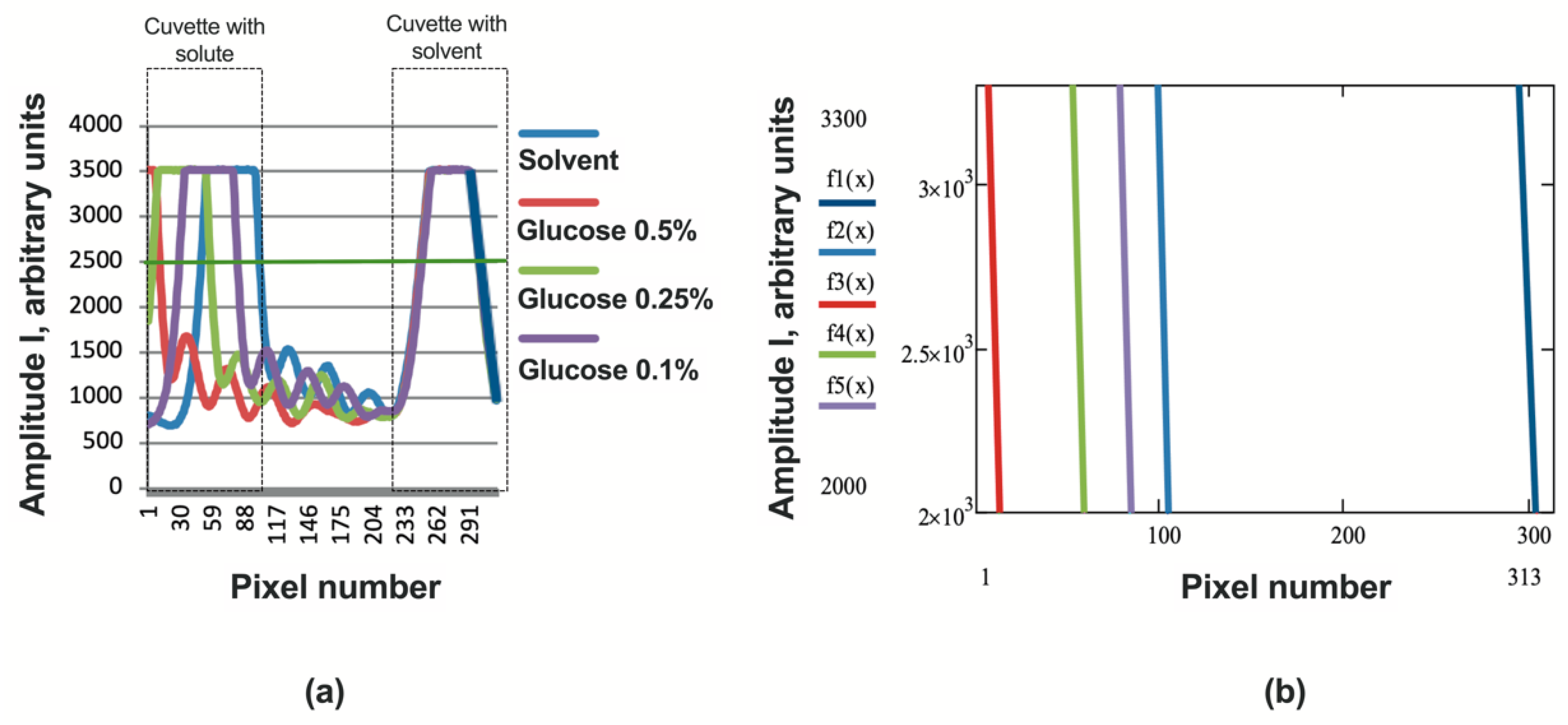

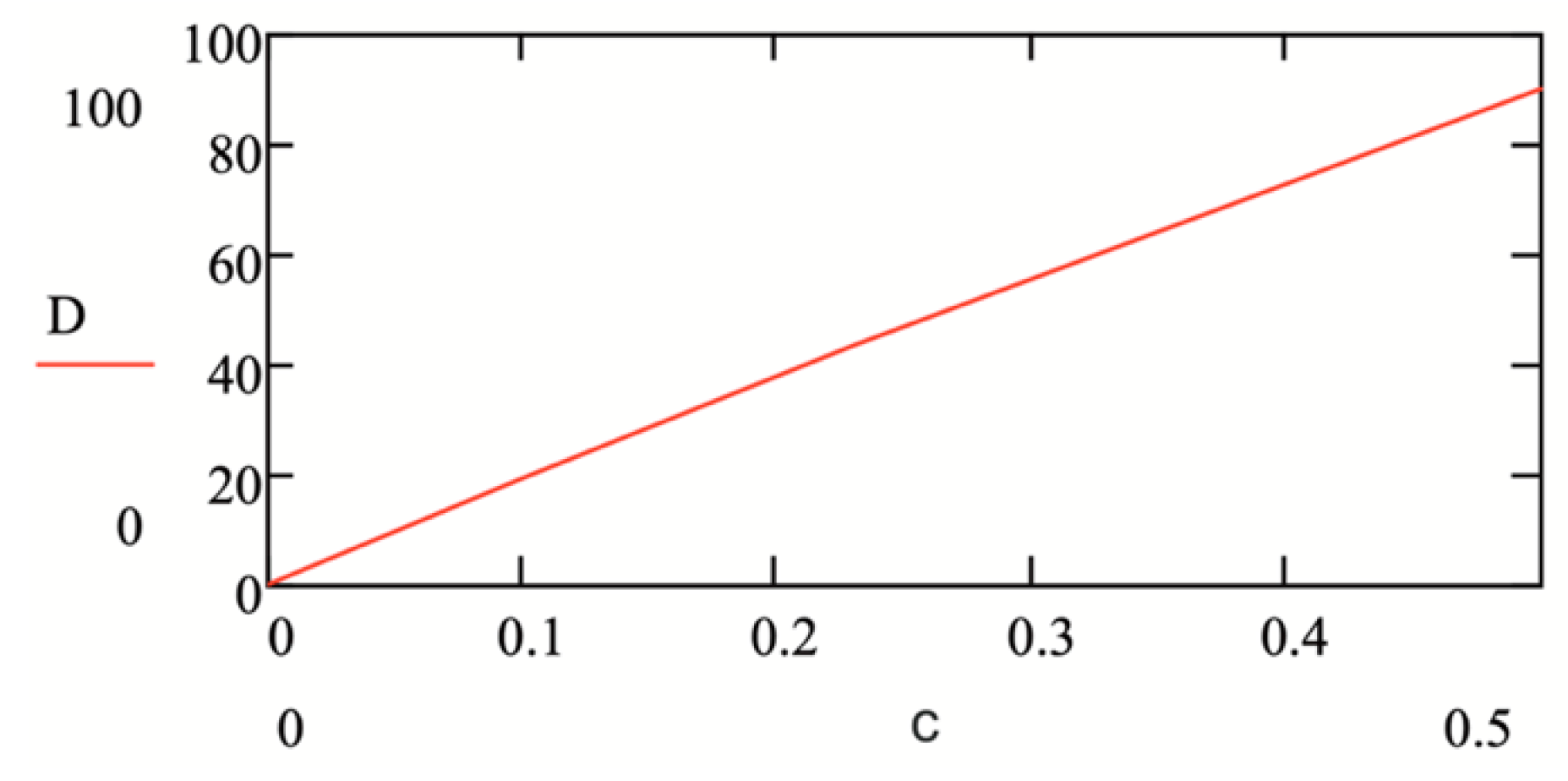

3. Design of the Differential Refractometer and Preliminary Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, S. Refractive Index Measurement and its Applications. Phys. Scr. 2002, 65, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeten, G.H. Refractive Index Measurement. In Measurement, Instrumentation and Sensors Handbook; Webster, J.G., Ed.; CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; pp. 1680–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Brice, B.A.; Halwer, M. A differential refractometer. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1951, 41, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.manualslib.com/manual/1404395/Wyatt-Technology-Optilab-Rex.html (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Longhurst, R.S. General and Physical Optics, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley Longman Ltd.: London, UK, 1974; p. 677. [Google Scholar]

- Vilitis, O.; Shipkovs, P.; Merkulov, D. Determining the refractive index of liquids using a cylindrical cuvette. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 117001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, V.; Merkulov, D.; Vilitis, O. New method for measuring refractive index of liquids. Proc. SPIE 2001, 4318, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, V.; Heinlaan, M.; Merkulov, D. Measurement of the concentration of functionalized polymer nanoparticles using light refraction. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference “Medical physics in the Baltic States”, Kaunas, Lituania, 7–9 November 2019; pp. 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.waters.com/webassets/cms/support/docs/71500241002r3.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Available online: https://infitek.com/products/automatic-abbe-digital-refractometer-rft-a731-and-rft-a733/ (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- García-Valenzuela, A. Beam refraction and displacement in a differentia refractometer with an absorbing sample. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 2192–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misto; Purwandari, E.; Supriydi; Arkundato, A.; Rohman, L.; Cahyono, B.E. Analyses of Concentration and Wavelength Dependent Refractive Index of Sugar Solution Using Sellmeier Equation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1825, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClimans, M.; LaPlante, C.; Bonner, D.; Bali, S. Real-time differential refractometry without interferometry at a sensitivity level of 10−6. Appl. Opt. 2006, 45, 6447–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsoumpos, S.; Giannios, P.; Triantis, D.; Moutzouris, K. Critical angle differential refractometry of lossy media: A theoretical study and practical design issues. Instruments 2019, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilio, S.C. A simple method to measure critical angles for high-sensitivity differential refractometry. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davydov, V.V.; Provodin, D.S.; Goldberg, A.A.; Kochetkov, I.D. A new method describing the change of the laser beam axis trajectory in the Anderson differential cuvette to measure the refractive index in liquids. Comput. Opt. 2024, 48, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Ngai, N.; Wu, C. A portable, stable and precise laser differential refractometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GESAMP. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Global Assessment; Kershaw, P.J., Ed.; IMO/ FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/ UN/UNEP/UNDP Joint group of experts on the scientific aspects of marine environmental protection; Reports and studies GESAMP; GESAMP: London, UK, 2015; Volume 93, p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, B.; Raffael, B.; Angers-Loustau, A.; Gilliland, D.; Kestens, V.; Petrillo, M.; Rio-Echevarria, I.M.; Van den Eede, G. Review of micro- and nanoplastic contamination in the food chain. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2019, 36, 639–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAPEA. Science Advice for Policy by European Academies. In A Scientific Perspective on Microplastics in Nature and Society; SAPEA: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besseling, E.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.; Foekema, E.M.; Koelmans, A.A. Quantifying ecological risks of aquatic micro- and nanoplastic. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 32–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá, L.C.; Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, F.; Rocha, T.L.; Futter, M.N. Studies of the effects of microplastics on aquatic organisms: What do we know and where should we focus our efforts in the future? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.B.; Bastos, A.S.; Justino, C.I.L.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P. Microplastics in the environment: Challenges in analytical chemistry—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1017, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Svirskis, Š.; Merkulovs, D.; Kozlovs, V. Proposal for a New Differential High-Sensitivity Refractometer for the Simultaneous Measurement of Two Refractive Indices and Their Differences. Sensors 2024, 24, 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113340

Svirskis Š, Merkulovs D, Kozlovs V. Proposal for a New Differential High-Sensitivity Refractometer for the Simultaneous Measurement of Two Refractive Indices and Their Differences. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113340

Chicago/Turabian StyleSvirskis, Šimons, Dmitrijs Merkulovs, and Vladimirs Kozlovs. 2024. "Proposal for a New Differential High-Sensitivity Refractometer for the Simultaneous Measurement of Two Refractive Indices and Their Differences" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113340

APA StyleSvirskis, Š., Merkulovs, D., & Kozlovs, V. (2024). Proposal for a New Differential High-Sensitivity Refractometer for the Simultaneous Measurement of Two Refractive Indices and Their Differences. Sensors, 24(11), 3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113340