Decentralized Navigation with Optimality for Multiple Holonomic Agents in Simply Connected Workspaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We navigate each agent with a sub-optimal policy to its destination. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work based on artificial potential fields that introduces optimality within a multi-agent navigation framework.

- No collision with other nearby agents or the workspace boundary occurs.

- Knowledge about the current position of the nearby agents and not their destination is required.

- The complexity is rendered linear with respect to the number of the agents and, if combined with the recent work [39], may be fixed.

2. Problem Formulation

3. Decentralized Navigation

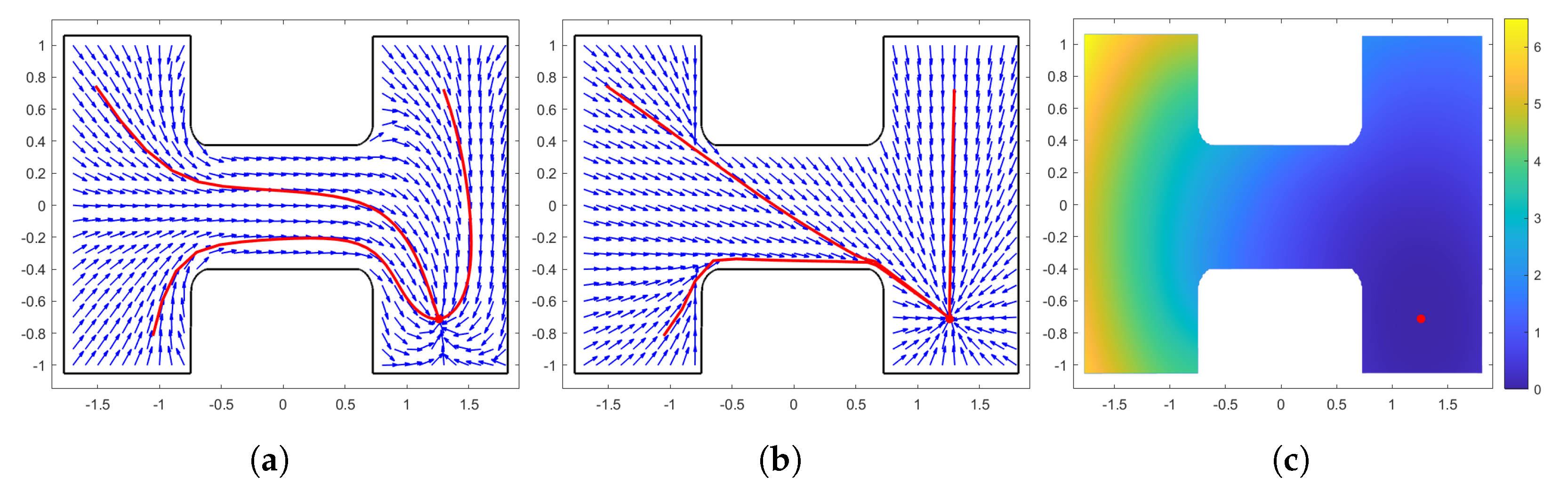

3.1. Navigation Function

- 1.

- It is analytic on F;

- 2.

- It has only one minimum at ;

- 3.

- Its Hessian at all critical points (zero gradient vector field) is full rank;

- 4.

- .

3.2. Individual Optimal Policy

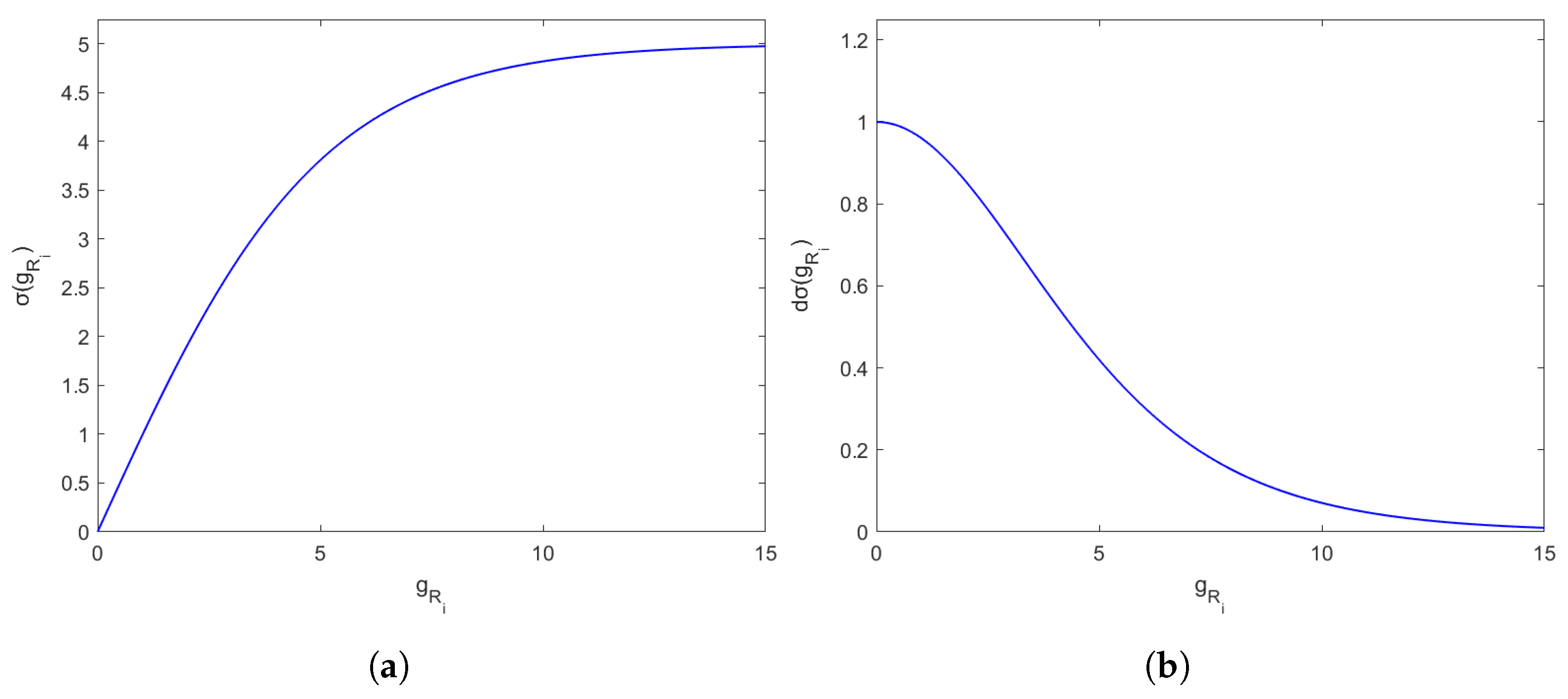

3.3. Resolving Conflicts via the Terms

3.3.1. Calculate Function

3.3.2. Calculate Function

4. Proof of Correctness

- The destination point .

- The free space boundary: .

- The set near collisions: .

- The set away from collision: .

- Since the workspace is connected, the destination point is a non-degenerate local minimum of .

- All critical points of are in the interior of the free space.

- For every , there exists a positive integer such that if , then there are no critical points of in .

- There exists an , such that has no local minimum in , as long as .

5. Results

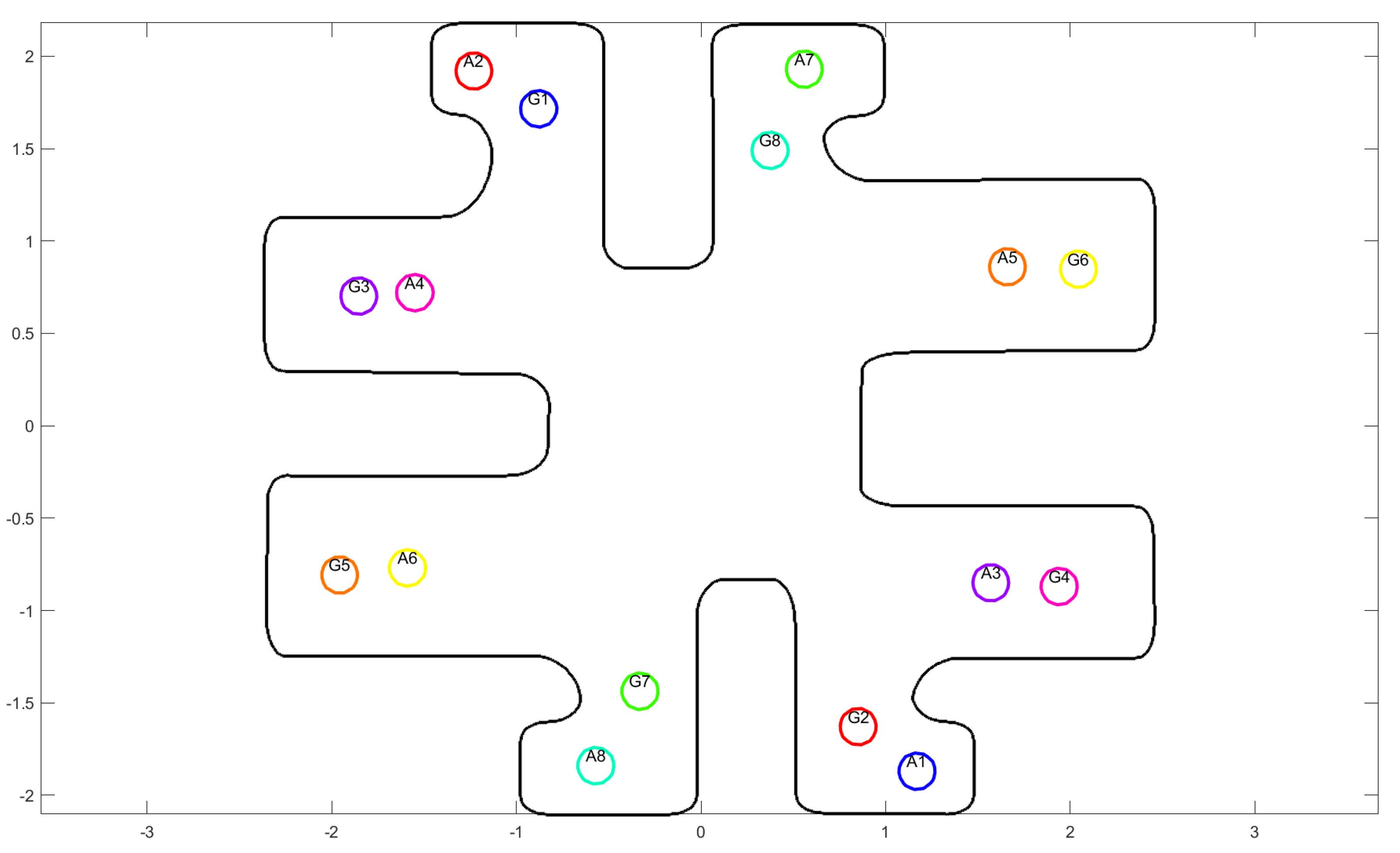

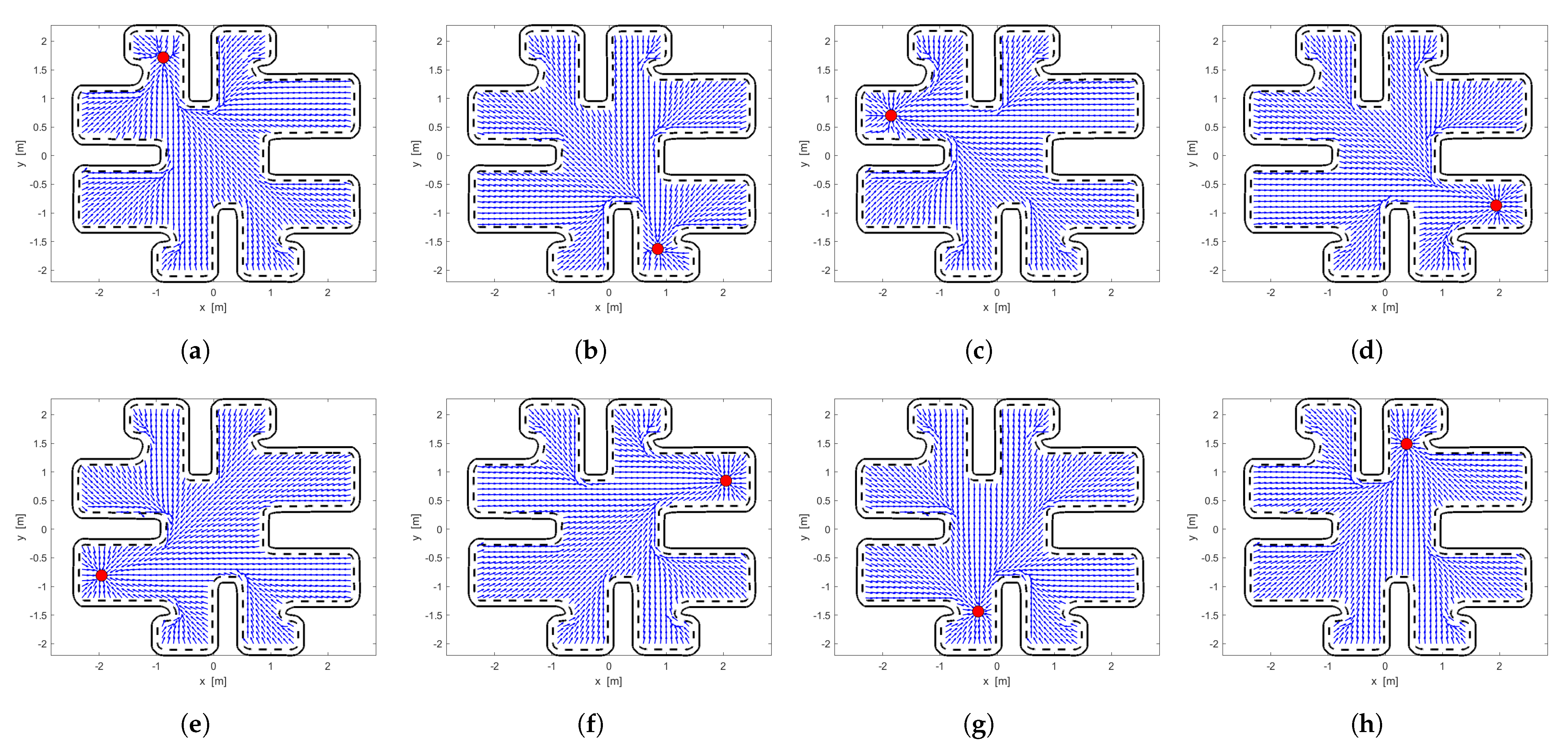

5.1. Multi-Agent Poli-RRT* Algorithm

5.2. Simulations

- Two members , , and .

- Four members and .

- Eight members (all the agents).

- Simulation 1: . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qLbfTVryj8 (accessed on 31 March 2024)

- Simulation 2: . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M2rhUSAz1w0 (accessed on 31 March 2024)

- Simulation 3: . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z__lYbZY7O0 (accessed on 31 March 2024)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MP | Motion Planning. |

| MAS | Multi-Agent System. |

| SAS | Single-Agent System. |

| CP | Centralized Policy. |

| DP | Decentralized Policy. |

| RRT | Rapidly-exploring Random Tree. |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning. |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning. |

| NF | Navigation Function. |

| AHPF | Artificial Harmonic Potential Field. |

| RPF | Relation Proximity Function. |

| RVF | Relation Verification Function. |

References

- Xuan, P.; Lesser, V.R. Multi-Agent Policies: From Centralized Ones to Decentralized Ones. In Proceedings of the First International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Bologna, Italy, 15–19 July 2002; pp. 1098–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Atinç, G.M.; Stipanovic, D.M.; Voulgaris, P.G. Supervised Coverage Control of Multi-Agent Systems. Automatica 2014, 50, 2936–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.; Mir, A.; Mir, I.; Mir, S.; Islaam, T.U.; Abualigah, L.; Forestiero, A. A Centralized Strategy for Multi-Agent Exploration. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 126871–126884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, J. Multi-Agent Robot Systems as Distributed Autonomous Systems. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2006, 20, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeh, A.E.; Mirjalili, S. Multi-Robot Exploration of Unknown Space Using Combined Meta-Heuristic Salp Swarm Algorithm and Deterministic Coordinated Multi-Robot Exploration. Sensors 2023, 23, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Tang, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y. MR-TopoMap: Multi-Robot Exploration Based on Topological Map in Communication Restricted Environment. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 10794–10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooker, M.N.; Birk, A. Multi-Robot Exploration under the Constraints of Wireless Networking. Control Eng. Pract. 2007, 15, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlonsoMora, J.; Baker, S.; Rus, D. Multi-Robot Formation Control and Object Transport in Dynamic Environments via Constrained Optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2017, 36, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borate, S.S.; Vadali, M. FFRRT: A Sampling-Based Path Planner for Flexible Multi-Robot Formations. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Advances in Robotics, Kanpur, India, 30 June–4 July 2021; pp. 53:1–53:6. [Google Scholar]

- Chipade, V.S.; Panagou, D. Multiagent Planning and Control for Swarm Herding in 2D Obstacle Environments under Bounded Inputs. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1956–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LópezNicolás, G.; Aranda, M.; Mezouar, Y. Adaptive Multi-Robot Formation Planning to Enclose and Track a Target with Motion and Visibility Constraints. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.D.C.; Indri, M.; Possieri, C.; Sassano, M.; Sibona, F. Path Planning in Formation and Collision Avoidance for Multi-Agent Systems. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2023, 47, 101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, G.; Niu, X.; Xia, C.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Sun, Y. A Hybrid Formation Path Planning Based on A* and Multi-Target Improved Artificial Potential Field Algorithm in the 2D Random Environments. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 54, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyassady, B.; de Berg, M.; Bringmann, K.; Buchin, K.; Fernau, H.; Halperin, D.; Kostitsyna, I.; Okamoto, Y.; Slot, S. Unlabeled Multi-Robot Motion Planning with Tighter Separation Bounds. In Proceedings of the 38th International Symposium on Computational Geometry, Berlin, Germany, 7–10 June 2022; pp. 12:1–12:16. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, B.L.; Harden, T.; Martínez, S. Multiagent Motion Planning with Sporadic Communications for Collision Avoidance. IFAC J. Syst. Control 2021, 15, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, L.; Marković, I.; Seder, M. Multiagent Gaussian Process Motion Planning via Probabilistic Inference. In Proceedings of the 12th IFAC Symposium on Robot Control, St Etienne, France, 17–19 May 2018; Volume 51, pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Vlantis, P.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Navigation of Multiple Disk-Shaped Robots with Independent Goals within Obstacle-Cluttered Environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; AlonsoMora, J. Chance-Constrained Collision Avoidance for MAVs in Dynamic Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koditschek, D.E.; Rimon, E. Robot Navigation Functions on Manifolds with Boundary. Adv. Appl. Math. 1990, 11, 412–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, S.G.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Closed Loop Navigation for Multiple Holonomic Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 September–4 October 2002; pp. 2861–2866. [Google Scholar]

- Zavlanos, M.M.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Decentralized Motion Control of Multiple Mobile Agents. In Proceedings of the 11th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation, Rhodes, Greece, 18–20 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Dawson, D.M.; Salah, M.; Burg, T. Cooperative Control of Multiple Vehicles with Limited Sensing. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2006, 21, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizou, S.G.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Closed Loop Navigation for Multiple Non-Holonomic Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Taipei, Taiwan, 14–19 September 2003; pp. 4240–4245. [Google Scholar]

- Loizou, S.G.; Lui, D.G.; Petrillo, A.; Santini, S. Connectivity Preserving Formation Stabilization in an Obstacle-Cluttered Environment in the Presence of TimeVarying Communication Delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 67, 5525–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, R.; Tanner, H.G. Flocking, Formation Control, and Path Following for a Group of Mobile Robots. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2015, 23, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Dimarogonas, D.V.; Loizou, S.G.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J.; Zavlanos, M.M. A Feedback Stabilization and Collision Avoidance Scheme for Multiple Independent Non-point Agents. Automatica 2006, 42, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, H.G.; Boddu, A. Multiagent Navigation Functions Revisited. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E. Sampling-Based Algorithms for Optimal Motion Planning. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2011, 30, 846–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vãras, L.G.D.; Medeiros, F.L.; Guimarães, L.N.F. Systematic Literature Review of Sampling Process in Rapidly-Exploring Random Trees. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 50933–50953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseas, P.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. A Continuous Off-Policy Reinforcement Learning Scheme for Optimal Motion Planning in Simply-Connected Workspaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 10247–10253. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos, C.; Rousseas, P.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Reinforcement Learning-Based Optimal Multiple Waypoint Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 1537–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Parras, J.; Apellániz, P.A.; Zazo, S. Deep Learning for Efficient and Optimal Motion Planning for AUVs with Disturbances. Sensors 2021, 21, 5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.F.; Liu, M.; Everett, M.; How, J.P. Decentralized Non-communicating Multi-Agent Collision Avoidance with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Benjeddou, A.; Mechbal, N.; Deü, J. Smart Structures and Materials: Vibration and Control. J. Vib. Control 2020, 26, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, M.; Chen, Y.F.; How, J.P. Motion Planning among Dynamic, Decision-Making Agents with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 3052–3059. [Google Scholar]

- Qie, H.; Shi, D.; Shen, T.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Joint Optimization of Multi-UAV Target Assignment and Path Planning Based on Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 146264–146272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartoretti, G.; Kerr, J.; Shi, Y.; Wagner, G.; Kumar, T.S.; Koenig, S.; Choset, H. PRIMAL: Path-Finding via Reinforcement and Imitation Multi-Agent Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 2378–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Wu, D.; Li, B.; Gao, X.; Hu, Z.; Chen, D. MEMADDPG: An Efficient Learning-Based Motion Planning Method for Multiple Agents in Complex Environments. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 2393–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseas, P.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Reactive Optimal Motion Planning to Anywhere in the Presence of Moving Obstacles. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2024, 02783649241245729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaglia, M.; Prandini, M.; Bascetta, L. Multi-Agent Poli-RRT* Optimal Constrained RRT-based Planning for Multiple Vehicles with Feedback Linearisable Dynamics. In Modelling and Simulation for Autonomous Systems, Proceedings of the Third International Workshop, MESAS 2016, Rome, Italy, 15–16 June 2016; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Peasgood, M.; Clark, C.M.; McPhee, J. A Complete and Scalable Strategy for Coordinating Multiple Robots within Roadmaps. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. Contributions to the Theory of Optimal Control. Bol. Soc. Mat. Mex. 1960, 5, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Song, R.; Lewis, F.L.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, H. Off-Policy Actor-Critic Structure for Optimal Control of Unknown Systems with Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 46, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseas, P.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Trajectory Planning in Unknown 2D Workspaces: A Smooth, Reactive, Harmonics-Based Approach. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 1992–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, A.D.; Xu, X.; Grizzle, J.W.; Tabuada, P. Control Barrier Function Based Quadratic Programs for Safety Critical Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 3861–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdisova, Z.; Skala, V. Radial Basis Function Approximations: Comparison and Applications. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 51, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaglia, M.; Prandini, M.; Bascetta, L. Poli-RRT*: Optimal RRT-based Planning for Constrained and Feedback Linearisable Vehicle Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 14th European Control Conference, Linz, Austria, 15–17 July 2015; pp. 2521–2526. [Google Scholar]

| Agent Index | Initial Position | Desired Position | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | x | y | |

| 1 | 1.17 | −1.87 | −0.88 | 1.72 |

| 2 | −1.23 | 1.92 | 0.85 | −1.63 |

| 3 | 1.57 | −0.85 | −1.85 | 0.70 |

| 4 | −1.55 | 0.72 | 1.94 | −0.85 |

| 5 | 1.66 | 0.86 | −1.96 | −0.81 |

| 6 | −1.59 | −0.77 | 2.04 | 0.85 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 1.93 | −0.33 | −1.44 |

| 8 | −0.57 | −1.84 | 0.37 | 1.49 |

| Agents Index | Time Duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal SAS | Simulation 1 | Simulation 2 | Simulation 3 | ||||

| Sub-Optimal | Poli-RRT* | Sub-Optimal | Poli-RRT* | Sub-Optimal | Poli-RRT* | ||

| 1 | 4.45 | 4.45 | 4.58 | 4.55 | 5.28 | 4.70 | 4.52 |

| 2 | 4.40 | 4.45 | 5.00 | 4.50 | 4.43 | 4.70 | 4.52 |

| 3 | 4.35 | 4.35 | 4.35 | 4.55 | 4.33 | 4.80 | 4.76 |

| 4 | 4.35 | 4.35 | 4.70 | 4.45 | 4.63 | 4.55 | 4.48 |

| 5 | 4.40 | 4.40 | 4.93 | 4.55 | 4.65 | 4.60 | 5.96 |

| 6 | 4.35 | 4.40 | 4.43 | 4.40 | 5.00 | 4.70 | 4.84 |

| 7 | 4.20 | 4.25 | 4.35 | 4.30 | 4.68 | 4.50 | 4.48 |

| 8 | 4.20 | 4.25 | 4.93 | 4.35 | 4.80 | 4.35 | 5.72 |

| Total | 34.70 | 17.45 | 19.56 | 9.10 | 10.28 | 4.80 | 5.96 |

| Agents Index | Cost Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal SAS | Simulation 1 | Simulation 2 | Simulation 3 | ||||

| Sub-Optimal | Poli-RRT* | Sub-Optimal | Poli-RRT* | Sub-Optimal | Poli-RRT* | ||

| 1 | 8.59 | 8.60 | 8.61 | 8.89 | 8.65 | 9.35 | 8.64 |

| 2 | 8.51 | 8.53 | 8.71 | 8.72 | 8.63 | 9.40 | 8.67 |

| 3 | 7.08 | 7.11 | 7.45 | 7.61 | 7.09 | 8.35 | 7.40 |

| 4 | 7.37 | 7.40 | 7.46 | 7.94 | 7.56 | 8.33 | 8.63 |

| 5 | 7.94 | 7.97 | 8.04 | 8.30 | 8.67 | 8.63 | 8.92 |

| 6 | 7.94 | 7.97 | 8.03 | 8.05 | 8.23 | 9.14 | 9.97 |

| 7 | 6.06 | 6.13 | 6.10 | 6.26 | 7.25 | 6.85 | 6.95 |

| 8 | 6.01 | 6.05 | 6.18 | 6.32 | 7.02 | 6.38 | 8.29 |

| Total | 59.51 | 59.75 | 60.58 | 62.09 | 63.10 | 66.43 | 67.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotsinis, D.; Bechlioulis, C.P. Decentralized Navigation with Optimality for Multiple Holonomic Agents in Simply Connected Workspaces. Sensors 2024, 24, 3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24103134

Kotsinis D, Bechlioulis CP. Decentralized Navigation with Optimality for Multiple Holonomic Agents in Simply Connected Workspaces. Sensors. 2024; 24(10):3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24103134

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotsinis, Dimitrios, and Charalampos P. Bechlioulis. 2024. "Decentralized Navigation with Optimality for Multiple Holonomic Agents in Simply Connected Workspaces" Sensors 24, no. 10: 3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24103134

APA StyleKotsinis, D., & Bechlioulis, C. P. (2024). Decentralized Navigation with Optimality for Multiple Holonomic Agents in Simply Connected Workspaces. Sensors, 24(10), 3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24103134