Robust Wheel Detection for Vehicle Re-Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

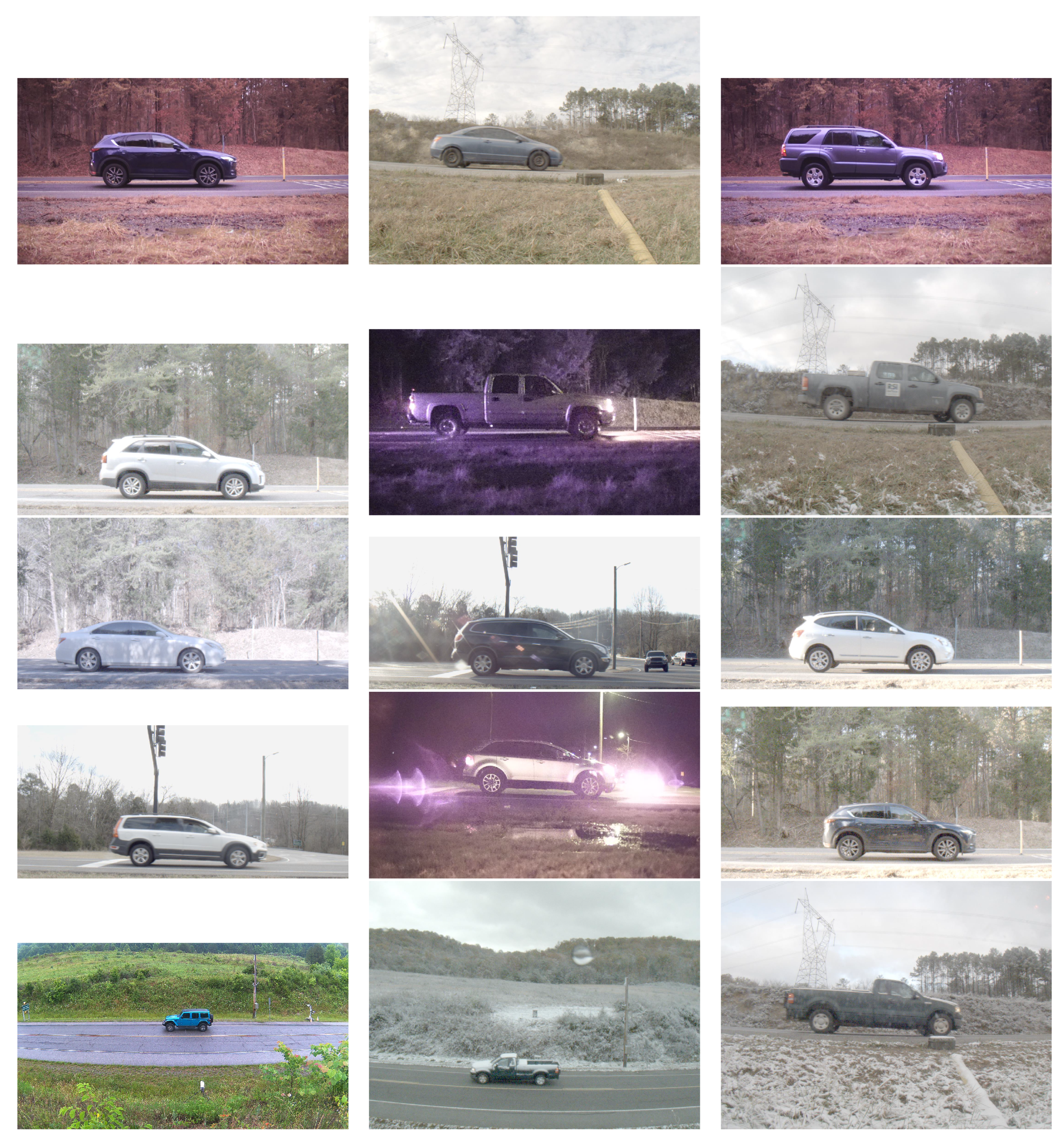

3. Dataset Description

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Vehicle Detection

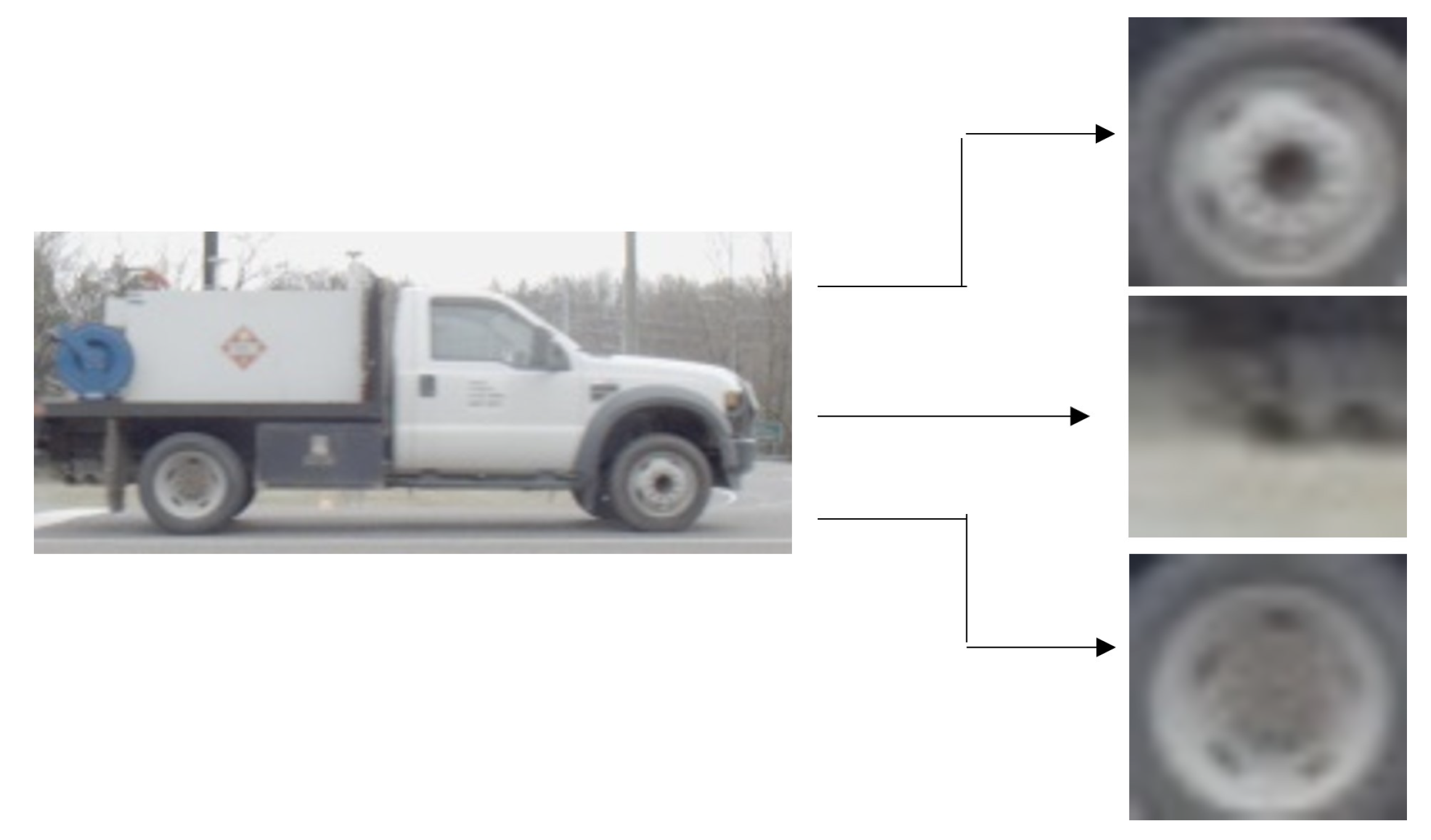

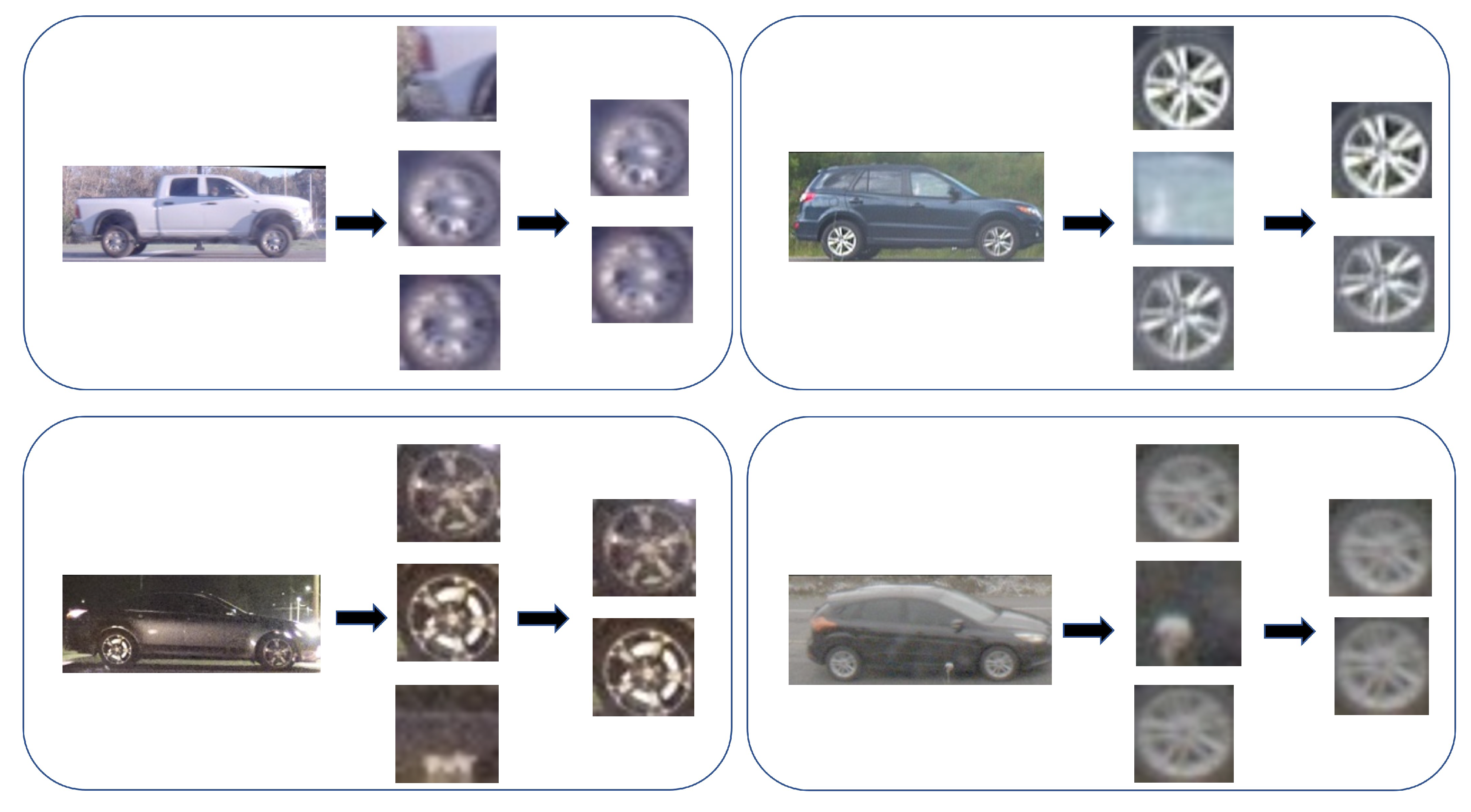

4.2. Wheel Detection

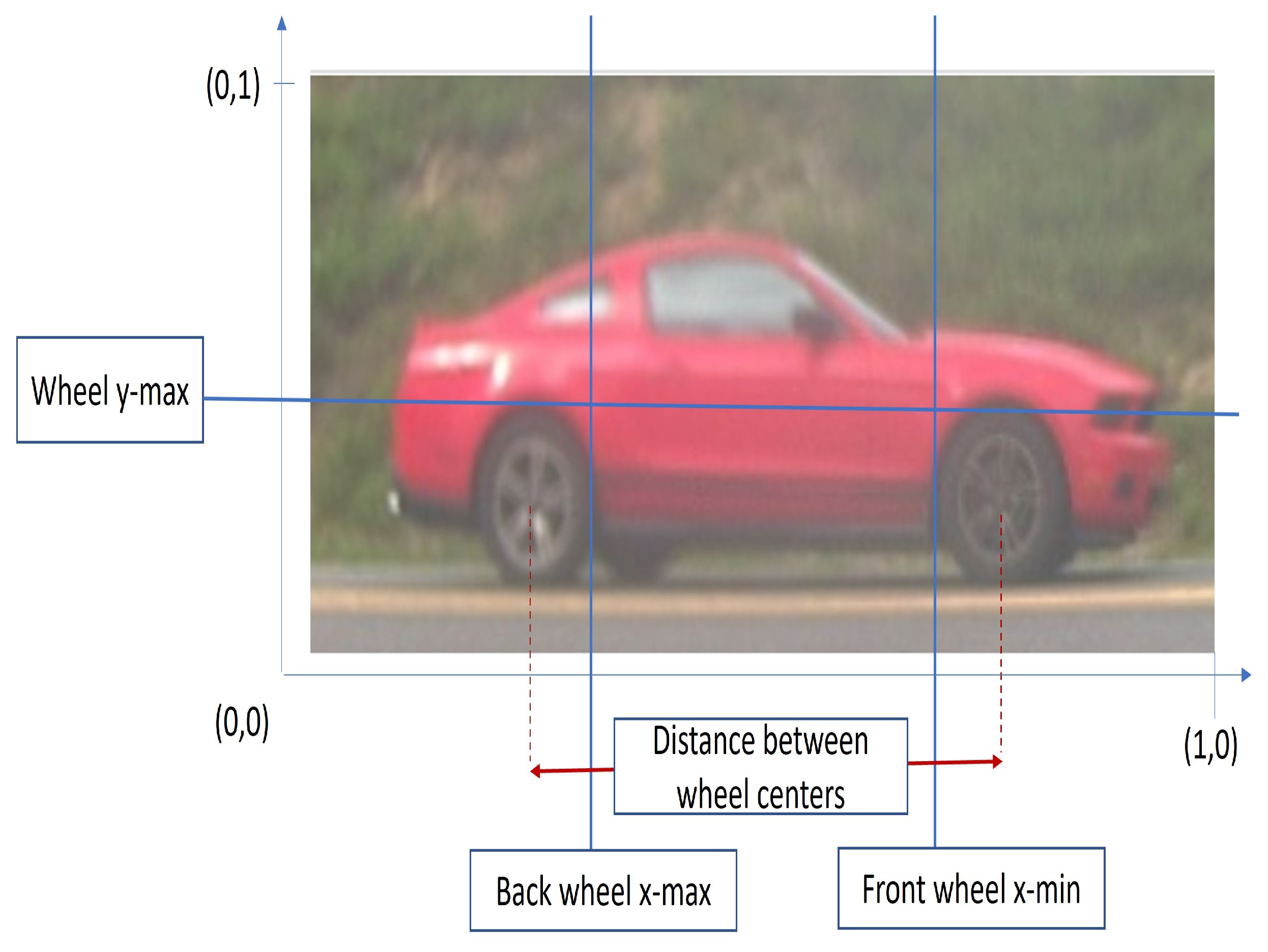

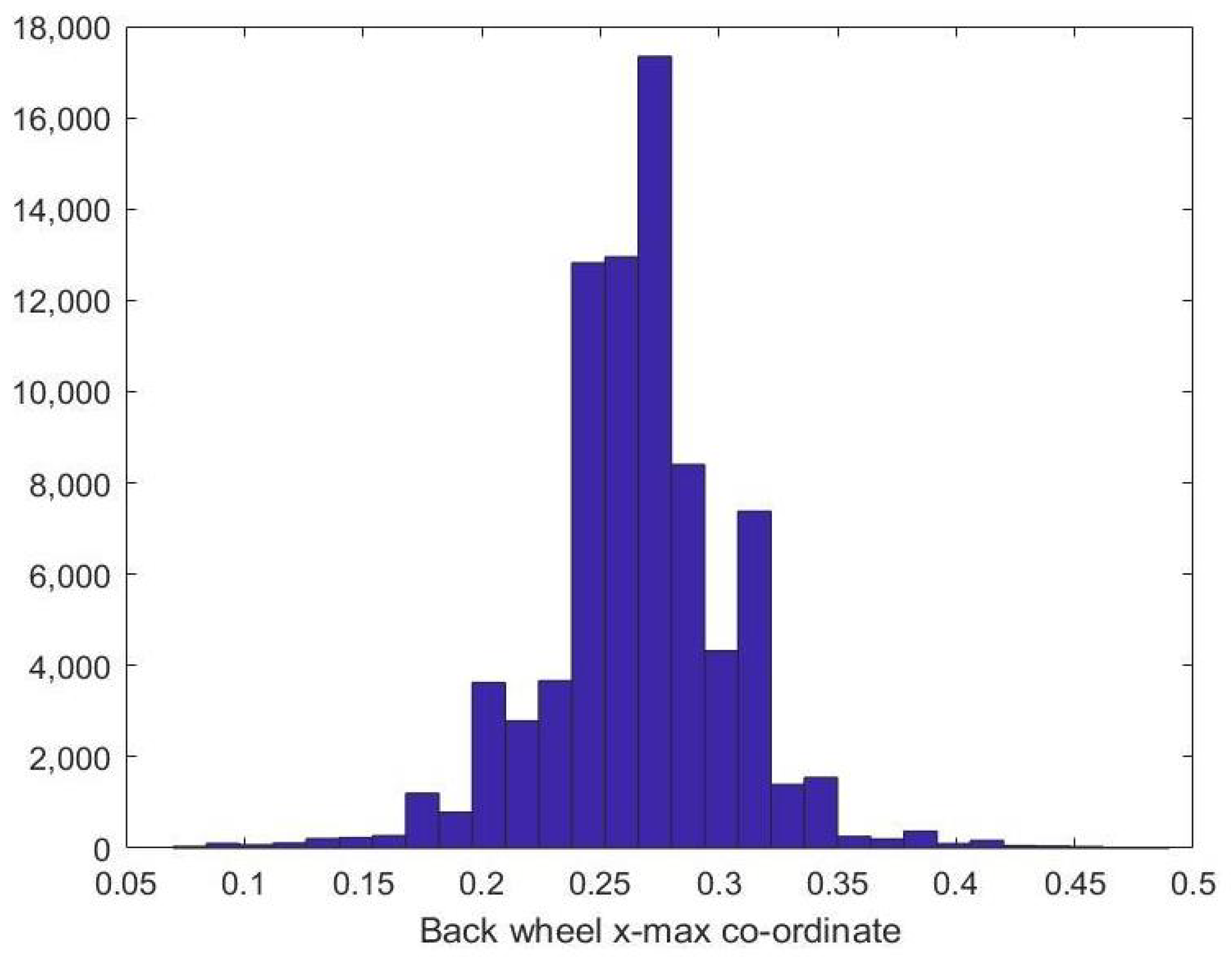

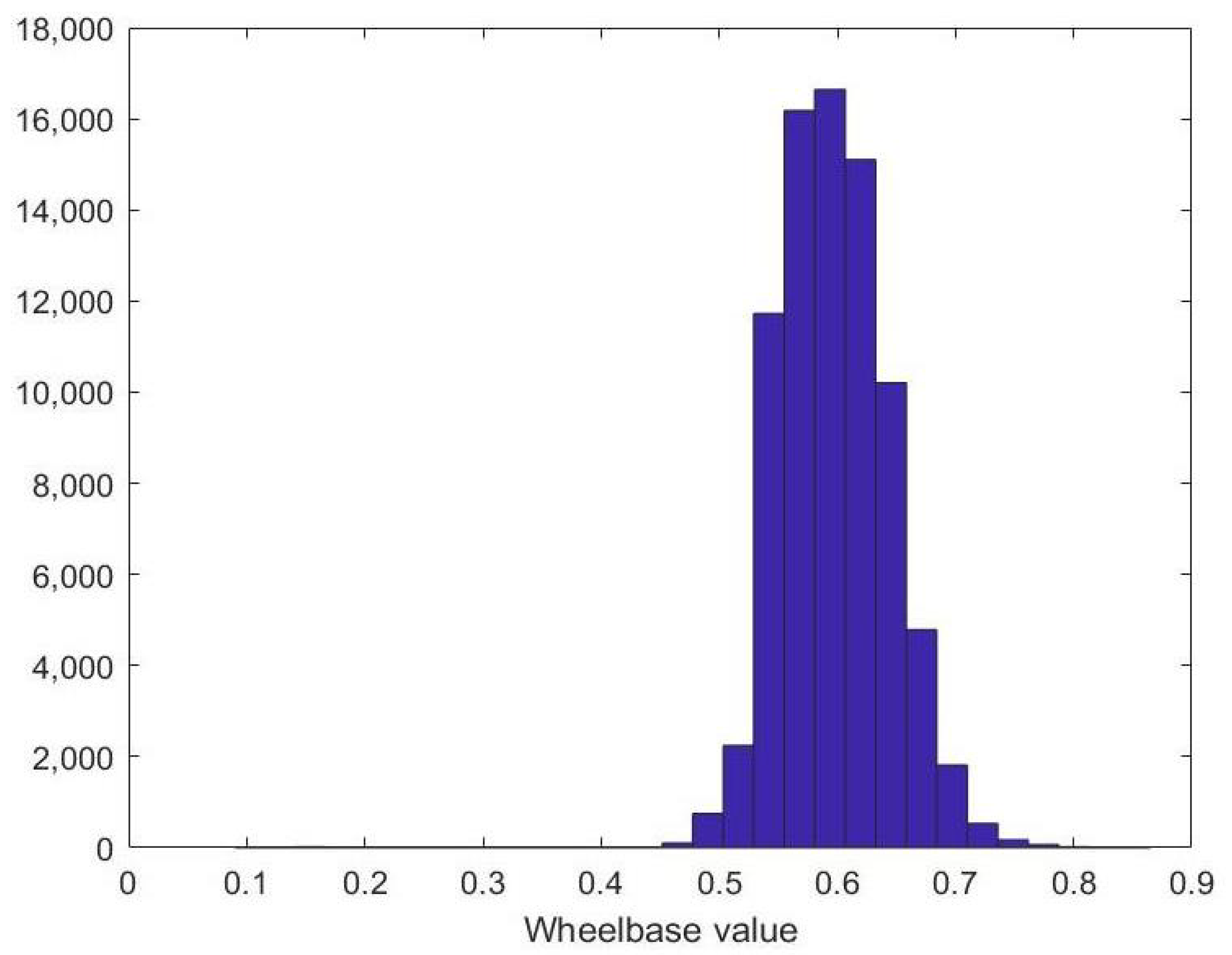

4.3. Wheel Selection

4.4. Experimental Results

4.5. Vehicle Re-Identification

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anagnostopoulos, C.; Alexandropoulos, T.; Loumos, V.; Kayafas, E. Intelligent traffic management through MPEG-7 vehicle flow surveillance. In Proceedings of the IEEE John Vincent Atanasoff 2006 International Symposium on Modern Computing (JVA’06), Sofia, Bulgaria, 3–6 October 2006; pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kathawala, Y.A.; Tueck, B. The use of RFID for traffic management. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2008, 8, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, R. Profile Images and Annotations for Vehicle Reidentification Algorithms (PRIMAVERA); Oak Ridge National Lab.(ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem, S.; Kerekes, R.A.; Tokola, R. Decision-Based Fusion for Vehicle Matching. Sensors 2022, 22, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Ma, H.; Fu, H. Large-scale vehicle re-identification in urban surveillance videos. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Seattle, WA, USA, 11–15 July 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sochor, J.; Špaňhel, J.; Herout, A. Boxcars: Improving fine-grained recognition of vehicles using 3-d bounding boxes in traffic surveillance. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 20, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanacı, A.; Zhu, X.; Gong, S. Vehicle re-identification in context. In German Conference on Pattern Recognition; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Duan, L. Veri-wild: A large dataset and a new method for vehicle re-identification in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3235–3243. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Mei, T.; Ma, H. Provid: Progressive and multimodal vehicle reidentification for large-scale urban surveillance. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2017, 20, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Q.; Gao, W. Ram: A region-aware deep model for vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Xiao, T.; Li, H.; Yi, S.; Wang, X. Learning deep neural networks for vehicle re-id with visual-spatio-temporal path proposals. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1900–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Q. Scan: Spatial and channel attention network for vehicle re-identification. In Pacific Rim Conference on Multimedia; Springer: Cham, Switzerlands, 2018; pp. 350–361. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y. Part-regularized near-duplicate vehicle re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3997–4005. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.-S.; Zhang, C.-L.; Liu, L.; Shen, C.; Wu, J. Coarse-to-fine: A RNN-based hierarchical attention model for vehicle re-identification. In Asian Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerlands, 2018; pp. 575–591. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.-Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.-T.; Wu, X. Object detection with deep learning: A review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3212–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.-E.; Sheikh, Y. Realtime multi-person 2d pose estimation using part affinity fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7291–7299. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Shelhamer, E.; Donahue, J.; Karayev, S.; Long, J.; Girshick, R.; Guadarrama, S.; Darrell, T. Caffe: Convolutional architecture for fast feature embedding. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM international Conference on Multimedia, Orlando, FL, USA, 7 November 2014; pp. 675–678. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Seff, A.; Kornhauser, A.; Xiao, J. Deepdriving: Learning affordance for direct perception in autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 2722–2730. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ma, H.; Wan, J.; Li, B.; Xia, T. Multi-view 3d object detection network for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1907–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Nevatia, R. A multi-scale cascade fully convolutional network face detector. In Proceedings of the 2016 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Cancun, Mexico, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 633–638. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerlands, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of theIn Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (NIPS 2015), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Zitnick, C.L.; Bala, K.; Girshick, B. Inside-outside net: Detecting objects in context with skip pooling and recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2874–2883. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerlands, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Tzutalin LabelImg. Free Software: MIT License; 2015. Available online: http://github.com/tzutalin/labelImg (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Chicco, D. Siamese neural networks: An overview. Artif. Neural Netw. 2021, 2190, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

| Baseline | Wheel Alignment + Wheel Selection | |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of retained vehicles after wheel detection | 98.78% | 99.34% |

| Percentage of images with correct detections | 77.03% | 91.41% |

| Baseline | Wheel Alignment + Wheel Selection | |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle re-ID performance | 91.2% | 92.02% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghanem, S.; Kerekes, R.A. Robust Wheel Detection for Vehicle Re-Identification. Sensors 2023, 23, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010393

Ghanem S, Kerekes RA. Robust Wheel Detection for Vehicle Re-Identification. Sensors. 2023; 23(1):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010393

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhanem, Sally, and Ryan A. Kerekes. 2023. "Robust Wheel Detection for Vehicle Re-Identification" Sensors 23, no. 1: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010393

APA StyleGhanem, S., & Kerekes, R. A. (2023). Robust Wheel Detection for Vehicle Re-Identification. Sensors, 23(1), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010393