A Systematic Review on Healthcare Artificial Intelligent Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Reporting standards

- Search strategy

- Study selection criteria

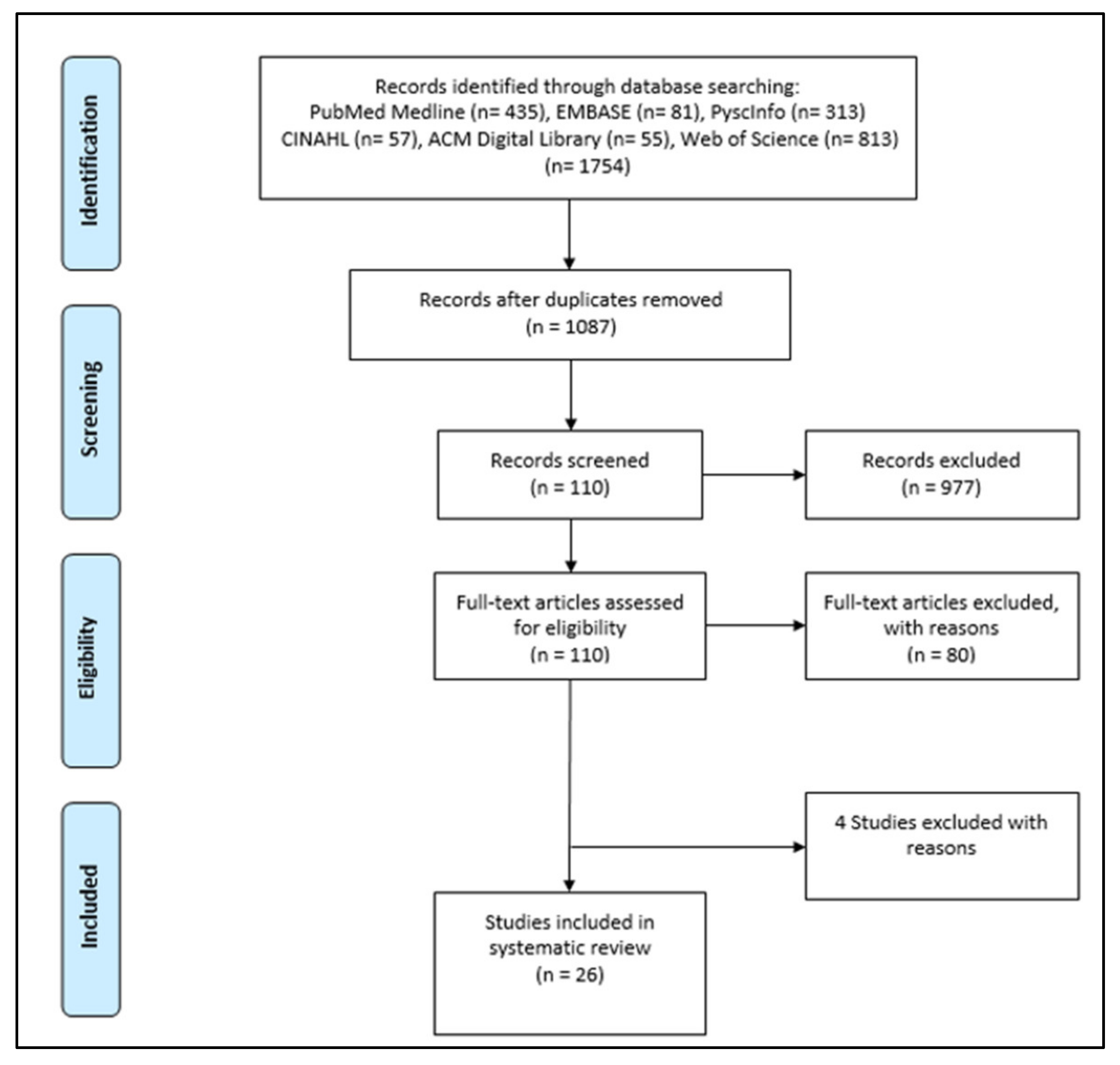

- Screening, data extraction, and synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

3.2. Description of Conversational Agents and AI Methods

3.3. Evaluation Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Study Protocol

| Topic | Content | |

| Title | Conversational Healthcare Agent for Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review | |

| Authors | Abdullah Bin Sawad, Baki Kocaballi, Mukesh Prasad, Bhuva Narayan, Ahlam Alnefaie, Ashwaq Maqbool, Indra Mckie, Jemma Smith, Berkan Yuksel | |

| Review team members and their organisational affiliations | Abdullah Bin Sawad 1 | (PhD Student) |

| Dr Baki Kocaballi 1 | (Lecturer) | |

| Dr Mukesh Prasad 1 | (Senior Lecturer) | |

| Dr Bhuva Narayan 2 | (Associate Professor) | |

| Ahlam Alnefaie 1 | (PhD Student) | |

| Dr Ashwaq Maqbool 3 | (Master Student) | |

| Indra Mckie 1 | (PhD Student) | |

| Jemma Smith 4 | (Bachelor Student) | |

| Berkan Yuksel 1 Deepak Puthal 5 | (Bachelor Student) (Assistant Professor) | |

| Contact details of the corresponding author | Abdullah Bin Sawad abdullahhatima.binsawad-1@student.uts.edu.au | |

| Organisational affiliation of the review | University of Technology Sydney | |

| Type and method of review | Systematic literature review | |

| Contributions | Study design: AS; Search strategy: AS; Screening: AS, AA, IM Data extraction and Data analysis: AS, AM, JS, BY; First draft: AS; Revisions and subsequent drafts: BK, MP, BN, DP; Critical feedback for the final draft: BK, MP, BN, DP | |

| Sources/Sponsors | NA | |

| Conflict of interest | None | |

| Rationale | What kinds of conversational agents are used for chronic conditions, what type of communication technology, what AI methods are used, what are the outcomes, the research gaps, and who are the target users/population group. | |

| Eligibility criteria | Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

| |

| Information sources | A database search will be conducted by accessing PubMed Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ACM Digital Library, and Web of Science databases. Search terms include synonyms, acronyms, and commonly known terms of the constructs “conversational agent” and “healthcare”. Grey literature will be excluded, such as posters, reviews, and presentations. | |

| Search strategy | The following search strategy will be used in the whole six databases. Filters: none Conduct started in February 2021 “Conversational agent” OR “conversational agents” OR “conversational system” OR “conversational systems” OR “dialog system” OR “dialog systems” OR “dialogue systems” OR “dialogue system” OR “assistance technology” OR “assistance technologies” OR “relational agent” OR “relational agents” OR “chatbot” OR “chatbots” OR “digital agent” OR “digital agents” OR “digital assistant” OR “digital assistants” OR “virtual assistant” OR “virtual assistants” AND “healthcare” OR “digital healthcare” OR “digital health” OR “health” OR “mobile health” OR “mHealth” OR “mobile healthcare”. | |

| Type of included study | Any primary research | |

| Studied domain | Chronic health conditions | |

| Population/Participants | Any population and any participants (caregivers, healthcare professionals, clinical/non-clinical, patients) | |

| Data collection and selection process | AS and AA will conduct the initial screening of the obtained studies based on titles and abstracts. Then, AS and IM will conduct full-text screening based on the eligibility/inclusion criteria. AS, AM, JS, and BY will extract data from eligible papers. Any disagreement will be discussed in the zoom meeting. Dr. Kocaballi and Dr. Prasad will supervise all these processes to ensure the measures are on the right path. | |

| Data items for coding | The following data items will be extracted from each included study: first author, year of publication, study location, study design/type, study aim, conversational agent evaluation measures, main reported outcomes and findings, type of chronic condition, type of study participants, type of the conversational agent, the goal of the conversational agent, communication channel, interaction modality, technique, system development. AS, AM, JS and BY will conduct the data extraction, and it will be discussed with Kocaballi and Dr Prasad. | |

| Outcomes and prioritisation | Main outcomes: Any healthcare related intervention outcomes (e.g., type of chronic condition, health goal, intervention targets), any architecture related outcomes (e.g., technique type, system development). Additional outcomes: Any conversational agent related outcomes (e.g., feasibility, accuracy, acceptability, functionality) and design features. | |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | AS and IM will review the included papers to appraise their quality. Disagreement will be discussed to reach a consensus. Any disagreement will be resolved with Dr Kocaballi and Dr. Prasad. | |

| Data synthesis | The PRISMA guidelines will be used for data synthesis. A narrative synthesis of the included studies will be performed. | |

| Language | English | |

| Country | Australia | |

| Anticipated or actual start date | February 2021 | |

| Anticipated or actual end date | September 2021 | |

| 1 School of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering and IT, University of Technology Sydney. 2 School of Communication, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney. 3 School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney. 4 School of Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and IT, University of Technology Sydney. 5 Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Khalifa University. | ||

Appendix B

| Artificial Intelligence or AI |

| Natural Language Understanding or NLU |

| Natural Language Processing or NLP |

| NR |

| neural networks |

| deep learning |

| machine learning |

| clustering/classification |

| unsupervised/supervised learning |

| CNN or convolutional neural network |

| Markov chain |

| hidden Markov chain |

| reinforcement learning |

| facial recognition |

| speech recognition |

| text analysis |

| sentiment analysis |

| natural language generation |

| text-to-speech or TTS |

| speech-to-text or STT |

| synthetic speech |

| spoken dialog system |

References

- Schachner, T.; Keller, R.; Wangenheim, F.V. Artificial Intelligence-Based Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions: Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, L.L.; Ter Stal, S.; Mulder, B.; De Vet, E.; Van Velsen, L. Developing Embodied Conversational Agents for Coaching People in a Healthy Lifestyle: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrand, J.; Hockensmith, R.; Houghton, R.F.; Walsh-Buhi, E.R. Evaluating Smart Assistant Responses for Accuracy and Misinformation Regarding Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Content Analysis Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Militello, L.K.; Huang, Y.; Lin, S. A scoping review of patient-facing, behavioral health interventions with voice assistant technology targeting self-management and healthy lifestyle behaviors. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 606–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safi, Z.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Khalifa, M.; Househ, M. Technical Aspects of Developing Chatbots for Medical Applications: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, A.C.; Xing, Z.; Khairat, S.; Wang, Y.; Bailey, S.; Arguello, J.; Chung, A.E. Conversational Agents for Chronic Disease Self-Management: A Systematic Review. In AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; American Medical Informatics Association: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021; pp. 504–513. [Google Scholar]

- McGreevey, J.D., 3rd; Hanson, C.W., 3rd; Koppel, R. Clinical, Legal, and Ethical Aspects of Artificial Intelligence–Assisted Conversational Agents in Health Care. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 324, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Kimani, E.; Trinh, H.; Pusateri, A.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Magnani, J.W. Managing Chronic Conditions with a Smartphone-based Conversational Virtual Agent. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, IVA 2018, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 5–8 November 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Díaz, Ó. Using Health Chatbots for Behavior Change: A Mapping Study. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S.; Ramo, D.; Chang, Y.-J.; Fu, M.; Moskowitz, J.; Haritatos, J. Use of the Chatbot “Vivibot” to Deliver Positive Psychology Skills and Promote Well-Being Among Young People After Cancer Treatment: Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, A. Augmented intelligence: Enhancing human capabilities. In Proceedings of the 2017 Third International Conference on Research in Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (ICRCICN), Kolkata, India, 3–5 November 2017; pp. 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, A.S.; Shah, N.; Bullock, K.D.; Arnow, B.A.; Bailenson, J.; Hancock, J. Key Considerations for Incorporating Conversational AI in Psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coiera, E.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Halamka, J.; Laranjo, L. The digital scribe. NPJ Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, S.; Vanderlip, E.; Sarvet, B. The Use of Health Information Technology Within Collaborative and Integrated Models of Child Psychiatry Practice. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 26, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, K.H.; Ly, A.-M.; Andersson, G. A fully automated conversational agent for promoting mental well-being: A pilot RCT using mixed methods. Internet Interv. 2017, 10, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, A.S.; Laranjo, L.; Kocaballi, A.B. Chatbots in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvedar, J.C.; Fogel, A.L.; Elenko, E.; Zohar, D. Digital medicine’s march on chronic disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, A.; Wang, Y.; Reiterer, H. Assistive Conversational Agent for Health Coaching: A Validation Study. Methods Inf. Med. 2019, 58, 009–023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevey, J.D.; Hanson, C.W.; Koppel, R.; Darcy, A.; Robinson, A.; Wicks, P. Conversational Agents in Health Care-Reply. JAMA 2020, 324, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, T.N.; Joerin, A.; Rauws, M.; Werk, L.N. Feasibility of pediatric obesity and prediabetes treatment support through Tess, the AI behavioral coaching chatbot. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 3.3 Chronic Conditions, Chapter 3 Causes of Ill Health. In Australia’s Health 2018; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2018; Volume 15. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6bc8a4f7-c251-4ac4-9c05-140a473efd7b/aihw-aus-221-chapter-3-3.pdf.aspx (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Dunkel-Jackson, S.M.; Dixon, M.R.; Szekely, S. Portable data assistants: Potential in evidence-based practice autism treatment. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Thompson, R.F.; Aneja, S.; Lehman, C.; Trister, A.; Zou, J.; Obcemea, C.; El Naqa, I. National Cancer Institute Workshop on Artificial Intelligence in Radiation Oncology: Training the Next Generation. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 11, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montenegro, J.L.Z.; da Costa, C.A.; da Rosa Righi, R. Survey of conversational agents in health. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 129, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaballi, A.B.; Quiroz, J.C.; Rezazadegan, D.; Berkovsky, S.; Magrabi, F.; Coiera, E.; Laranjo, L. Responses of Conversational Agents to Health and Lifestyle Prompts: Investigation of Appropriateness and Presentation Structures. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Dunn, A.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chen, J.; Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Gallego, B.; Magrabi, F.; Lau, A.Y.; et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baptista, S.; Wadley, G.; Bird, D.; Oldenburg, B.; Speight, J. The My Diabetes Coach Research Group Acceptability of an Embodied Conversational Agent for Type 2 Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support via a Smartphone App: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, J.; Consigli, A.; Clark, C.; Robinson, K.J. Getting Ready for Adult Healthcare: Designing a Chatbot to Coach Adolescents with Special Health Needs Through the Transitions of Care. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 49, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskar, K.; Schlenk, E.; Callan, J.; Bickmore, T.; Sereika, S. Relational Agents as an Adjunct in Schizophrenia Treatment. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2011, 49, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Caldwell, P. Improving Health Outcomes Sooner Rather Than Later via an Interactive Website and Virtual Specialist. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2017, 22, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Han, S.; Lee, K.; Kang, Y. Simple and Steady Interactions Win the Healthy Mentality: Designing a Chatbot Service for the Elderly. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 4, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Wilkes, C.; Rowan, K.; Toledo, A.; Paradiso, A.; Czerwinski, M.; Mark, G.; Linehan, M.M. Pocket Skills: A conversational Mobile web app to support dialectical behavioral therapy. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; p. 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, B.; Bibault, J.-E.; Pienkowski, A.; Delamon, G.; Guillemassé, A.; Nectoux, P.; Brouard, B. When Chatbots Meet Patients: One-Year Prospective Study of Conversations between Patients with Breast Cancer and a Chatbot. JMIR Cancer 2019, 5, e12856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, K.; Potter, S.; Bec, R.; Bennion, M.; Christensen, H.; Grindell, C.; Mirheidari, B.; Weich, S.; De Witte, L.; Wolstenholme, D.; et al. A Virtual Agent to Support Individuals Living with Physical and Mental Comorbidities: Co-Design and Acceptability Testing. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser-Ulrich, S.; Künzli, H.; Meier-Peterhans, D.; Kowatsch, T. A Smartphone-Based Health Care Chatbot to Promote Self-Management of Chronic Pain (SELMA): Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e15806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inkster, B.; Sarda, S.; Subramanian, V. An Empathy-Driven, Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agent (Wysa) for Digital Mental Well-Being: Real-World Data Evaluation Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lobo, J.; Ferreira, L.; Ferreira, A.J. CARMIE: A conversational medication assistant for heart failure. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. 2017, 8, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neerincx, M.A.; Van Vught, W.; Henkemans, O.B.; Oleari, E.; Broekens, J.; Peters, R.; Kaptein, F.; Demiris, Y.; Kiefer, B.; Fumagalli, D.; et al. Socio-Cognitive Engineering of a Robotic Partner for Child’s Diabetes Self-Management. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehman, U.U.; Chang, D.J.; Jung, Y.; Akhtar, U.; Razzaq, M.A.; Lee, S. Medical Instructed Real-Time Assistant for Patient with Glaucoma and Diabetic Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Hara, D.M.; Seagriff-Curtin, P.; Levitz, M.; Davies, D.; Stock, S. Using Personal Digital Assistants to improve self-care in oral health. J. Telemed. Telecare 2008, 14, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, J.; Richards, D. Changing stigmatizing attitudes to mental health via education and contact with embodied conversational agents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzini, I.; Falavigna, D.; Giorgino, T.; Gretter, R.; Quaglini, S.; Rognoni, C.; Stefanelli, M. Automated Spoken Dialog System for Home Care and Data Acquisition from Chronic Patients. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2003, 95, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Puskar, K.; Schlenk, E.A.; Pfeifer, L.M.; Sereika, S.M. Maintaining reality: Relational agents for antipsychotic medication adherence. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, N.; Wexler, S.; Drury, L.; Pollak, C.; Wang, V.; Scher, K.; Narducci, S. A Protocol-Driven, Bedside Digital Conversational Agent to Support Nurse Teams and Mitigate Risks of Hospitalization in Older Adults: Case Control Pre-Post Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Philip, P.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Sagaspe, P.; de Sevin, E.; Olive, J.; Bioulac, S.; Sauteraud, A. Virtual human as a new diagnostic tool, a proof of concept study in the field of major depressive disorders. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piau, A.; Crissey, R.; Brechemier, D.; Balardy, L.; Nourhashemi, F. A smartphone Chatbot application to optimize monitoring of older patients with cancer. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 128, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamekhi, A.; Bickmore, T. Breathe Deep: A breath-sensitive interactive meditation coach. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielman, M.L.; Neerincx, M.A.; Bidarra, R.; Kybartas, B.A.; Brinkman, W.-P. A Therapy System for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Using a Virtual Agent and Virtual Storytelling to Reconstruct Traumatic Memories. J. Med. Syst. 2017, 41, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthal, D.; Mir, Z.H.; Filali, F.; Menouar, H. Cross-layer architecture for congestion control in Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Connected Vehicles and Expo (ICCVE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2–6 December 2013; pp. 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Puthal, D. Lightweight Multi-party Authentication and Key Agreement Protocol in IoT-based E-Healthcare Service. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 2021, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickmore, T.W.; Mitchell, S.; Jack, B.W.; Paasche-Orlow, M.; Pfeifer, L.M.; O’Donnell, J. Response to a relational agent by hospital patients with depressive symptoms. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dworkin, M.; Chakraborty, A.; Lee, S.; Monahan, C.; Hightow-Weidman, L.; Garofalo, R.; Qato, D.; Jimenez, A. A Realistic Talking Human Embodied Agent Mobile Phone Intervention to Promote HIV Medication Adherence and Retention in Care in Young HIV-Positive African American Men Who Have Sex With Men: Qualitative Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e10211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthal, D.; Ranjan, R.; Nanda, A.; Nanda, P.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Zomaya, A. Secure authentication and load balancing of distributed edge datacenters. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2019, 124, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.P.S.; Rath, S.; Puthal, D. Energy Efficient Protocols for Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey and Approach. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2012, 44, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthal, D.; Nepal, S.; Ranjan, R.; Chen, J. A secure big data stream analytics framework for disaster management on the cloud. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 18th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications; IEEE 14th International Conference on Smart City; IEEE 2nd International Conference on Data Science and Systems (HPCC/SmartCity/DSS), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 1218–1225. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Study Location | Type of Chronic Condition | Study Aim | Study Type and Methods | Participants’ Characteristics | Evaluation Measures and Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User Experience | Health Related Measures | ||||||

| Azzini et al., 2003 | Italy | Hypertension (patients with essential hypertension) | Data collection, developing a prototype home monitoring system. | Quasi-experimental (150 dialogues; 15 patients with essential hypertension entered the data at home; physicians used interface to store and update patient information). | Fifteen patients with no information about age, gender and duration. | Not reported | Not reported |

| Baptista et al., 2020 | Australia–New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, and Western Australia | Diabetes–Type 2 (T2D) | Self-management, education, and support. | Qualitative (six months baseline; 66 of the 93 patients completed a survey). Quantitative (between October 2017 to February 2018; 16 of the total patients had semi-structured interviews). RCT (testing the effectiveness of the T2D self-management smartphone app). | Ninety-three patients from My Diabetes Coach app. Sixty-six responses in 6 months post baseline. Nineteen of these respondents participated in the interviews. Avg. age: 57; male: 33; female: 33. | User experience feedback is as the following: helpful and friendly (86%), competent (85%), trustworthy (73%), likable (61%), not real (27%), boring (39%), annoying (30%), more motivated (44%), comfortable (36%), confident (21%), happy (17%), hopeful (12%), frustrated (20%), and feel guilty (17%). |

|

| Beaudry et al., 2019 | America-Vermont | Chronic condition (teenagers with pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Cardiology, or Type 1 Diabetes) | Learning self-care for teenagers (transition from pediatric to adult) with a chronic condition. | Quasi-experimental (24 weeks; pilot study on 13 teenagers with a chronic medical condition using a text messaging platform (chatbot) with scripted interactions) | Thirteen teenagers from the University of Vermont Children’s Hospital. Age: 14–17; duration: 24 weeks. |

| Participants suggest this chatbot should be expanded, and that it shows promise to help teenagers attain self-care skills on the transition journey. |

| Bickmore et al., 2010 | America-Boston | Depressive Symptoms | Hospital patients know about their post-discharge self-care regimen through an automated system. | Quasi-experimental (one month; 131 patients interacted with the agent from their hospital beds; two rounds of pilot studies to assess usability, acceptance, and satisfaction with the agent; 347 subjects were enrolled and randomized; only 173 subjects were used into the relational agent of the study; nurses to follow up with patients). | One hundred and thirty patients from Boston Medical Centre. Age: 18; male: 70; female: 60; duration: 30 days. |

|

|

| Bickmore et al., 2010 | America-Pennsylvania | Schizophrenia | Promoting antipsychotic medication adherence for patients with schizophrenia. | Quasi-experimental (initial range of responses, then modifying the list as needed to pilot testing). RCT (1–2 months; two RCTs. One with young adults (Bickmore et al., 2005 a, b) and another with geriatric patients (Bickmore et al., 2005a); both were conducted on home desktop computers). | Twenty patients from a mental health outpatient clinic. Age: 19–58; male: 67%; female: 33%; duration: 1–2 months. The nurse visited each participant’s home to explain how to use the computer and to make sure the software worked normally. |

|

|

| Bott et al., 2019 | America-New York | Loneliness, Depression, Delirium, Falls | Supporting nurses and mitigating risks of hospitalization for elders. | Quasi-experimental (2 groups; group 1 (intervention)—41 participants received an avatar for the duration of their hospital stay, group 2—(control) 54 participants received a daily 15 min visit from a nursing student). | Ninety-five elders from an urban community hospital in New York. Age: over 65 years; male: 43; female: 52; the average length of stay for a patient: 3–6 days. | The mean for patient engagement data was as follows: number of check-ins: 71.30/day; observational and engagement time: 61 min/day; media files used: 11.50/day; completed protocol tasks: 6.5 tasks/day. |

|

| Chaix et al., 2019 | France and Europe | Breast Cancer | Support, education, and improving medication adherence. | Analysis (1 year; 4737 patients, collecting data to analyze the number of conversations between patients and chatbot) + Prospective study (8 months; 958 patients received a weekly survey). | Analysis for the conversations between patients and chatbot (Vik). Patients: 4737; male: 526; female: 4211; avg age: 48; duration: 1 year. Prospective study patients: 958; duration: 8 months; no details about gender. |

| Not reported |

| Dworkin et al., 2018 | America- Chicago | HIV | Promoting HIV medication adherence and retention in care. | Iterative approach (five months; 16 men; five iterative focus groups to develop the phone app, each group have 3–4 participants; participants were divided based on the questionnaire they filled out). | Sixteen men participated (African American men who have sex with men) recruited from four Universities of Illinois at Chicago. Age: 18–34; duration: January to May 2016. |

|

|

| Easton et al., 2019 | UK | Patients with an Exempla r Long-Term Condition (LTC; Chronic Pulmonary Obstructive Disease (COPD)) | Data collection, support, self-management, and diagnosis. | Co-design workshop (10 patients; 2 co-design workshops including health professionals and patients to fill out questionnaires). | Ten patients were identified through the local British Lung Foundation Breathe Easy support group. Avg. age: 71; male: 5; female: 5. Workshop 1 was run in July 2017 and lasted 5 h. Workshop 2 was run in October 2017 and lasted 5 h. |

| Not reported |

| Greer et al., 2019 | America | After Cancer Treatment | Support and follow-up | RCT (8 weeks; 45 young adults; 2 groups, group 1 was experimental group (25 young adults), group 2 was control group (20 young adults); all participants filling-out a survey at baseline). | Forty-five young adults from Facebook advertising, survivorship organizations and direct email. Age: 18–29; male: 9; female: 36; duration: 8 weeks. |

|

|

| Hauser-Ulrich et al., 2019 | German and Swiss | Self-Management of Chronic Pain | Pain self-management | RCT (8 weeks; 102 participants were recruited online, 59 of them were in the intervention group (cognitive behaviour therapy), and the rest were in the control group are not related to pain management). | One hundred and two participants from the SELMA app. Avg. age: 43.7 years; male: 14; female: 88; duration: 2 months. |

|

|

| Inkster et al., 2018 | America- Brooklyn and Chicago | Symptoms of Depression | Data collection and self-reported symptoms of depression | Quasi-experimental (11 July 2017, and 5 September 2017; 129 users were divided into two groups (high users and low users); quantitative was to check the impact of the intervention; qualitative was to check the user experience with Wysa app). | One hundred and twenty-nine users from the Wysa app (high users, n = 108; low users, n = 21). No. of female and male: not reported; duration: 11 July 2017 to 5 September 2017. |

| Not reported |

| Lobo et al., 2017 | Portugal | Heart Failure Care and Pharmacological Information | Managing information about medicines and increasing adherence | Survey (11 adults; participants filled out a questionnaire to assess system’s performance, feasibility, and drawbacks). | Eleven native Portuguese adults. Age: 22–33; no information about gender and duration. |

| CARMIE has proven the capability of addressing the pharmacological and treatment information for heart failure daily care. |

| Neerincx et al., 2019 | Netherlands and Italy | Diabetes–Type 1 (T1DM) | Support and manage children diabetes | Iterative refinement process (6 months; this process went through three cycles that include knowledge base, interaction, and some functions to achieve an effective partner for diabetes management). | Children from diabetes camps and hospitals in Netherlands and Italy. Age: 7–14; duration: 6 months. |

|

|

| Rehman et al., 2020 | Korea | Glaucoma and Diabetic Conditions | Data collection and diagnosing | Experimental method (60 min per patient; 11 groups based on availability and feasibility (three patients per group); each patient interacted with the chatbot individually) (119 responses from 11 countries (overseas students) for the questionnaire were sent by email from the university)). | Thirty-three international students from the University of Kyung Hee. Age: 18–43; male: 20; female: 13; 60 min per patient. | Using Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient correlation of items per scale: attractiveness: 0.74; perspicuity: 0.67; efficiency: 0.77; dependability: 0.60; stimulation: 0.67; novelty: 0.48. | Not reported |

| Stephens et al., 2019 | America- Boston | Obesity and Prediabetes | Self-reported progress, support and follow-up with a clinician | Feasibility study (6 months; 23 youth encouraged to use Tess chatbot to help users to achieve the progress). | Twenty-three youths with obesity symptoms from children’s healthcare system. Age: 9.78–18.54; male: 10; female: 13; duration: 6 months. | Ninety-six percent of the total patients reported this chatbot is helpful. | Not reported |

| O’Hara et al., 2008 | America | Intellectual Disabilities; Poor Dental Hygiene | Education and self-management | Quasi-experimental (6 months; 36 dental patients used personal assistive devices (PDs) and had their oral health tracked by a dentist). | Thirty-six participants from a single dental practice. No information about age and gender; 9 participants left study partway through; duration: 6 months. | More than half of participants reported PDAs not functioning correctly (mostly problems keeping the battery charged). | Ten participants (40%) achieved improvement in at least three areas of oral health. |

| Philip et al., 2017 | France | Major Depressive Disorders (MDD) | Clinical interview (major depressive disorder diagnosis) | Clinical interviews (179 participants with major depressive disorders; interview 1 with CA, interview 2 with sleep clinic psychiatrist). | One hundred and seventy-nine outpatients from a sleep clinic in Bordeaux University Hospital. Age: 18–65; male: 42.5%; female: 57.5%; duration: November 2014 to June 2015. |

| Not reported |

| Piau et al., 2019 | France | Cancer (Geriatric Oncology) | Data collection | Quasi-experimental (7 weeks; 9 participants to test semi-automated CA). | Nine participants (undergoing chemotherapy after cancer diagnosis). Age: +65; male: 5; female: 4; duration: 6 months. |

| Not reported |

| Puskar et al., 2011 | America | Schizophrenia | Treatment, support and education. | Quasi-experimental (1 month; 17 participants from a local outpatient clinic given laptop computers with a relational agent) | Seventeen patients completed the study, but only results from two participants were mentioned in the study. Age: 18–55; the majority is female; duration: 1 month. |

| Before CA, the participants had an adherence level of 21%, but with the CA, the rate rose to 46%. |

| Richards and Caldwell, 2018 | Australia | Urinary Incontinence | Treatment and education | Quasi-experimental ((Pilot studies 1,2,3; 62 patients used web-based eADVICE service (without an added ECA) prior to consultation, with a specialist; study 1—10 patients (2012), study 2—25 patients (2013), study 3—27 patients (2014)) (pilot study 4; 13 patients; testing initial reactions to an ECA called “Dr Evie”. (pilot study 5; over 6 months; 29 participants tested usability and usefulness of eADVICE service + Dr Evie and patient adherence)). | Children with urinary incontinence. Age: 6–16; 79 families enrolled; 74 completed pre-study survey; males: 44; females: 30; duration: not reported. |

|

|

| Ryu et al., 2020 | South Korea | Mental Health (Depression and Anxiety) | Treatment | Quasi-experimental Initial field study (1 day; 24 older adults; 10 min of use, video recording hands and screen; thematic analysis of interviews to find five features). Beta-testing field study (2 weeks; 25 older participants; 4 excluded from analysis; chat-initiated message three times a day; Epidemiologic Studies Depression and Beck Anxiety Inventory scales used before and after testing; negative polarity analysis of chat). | Initial testing had 24 older adults. male: 7; female: 17. Beta-testing had 25 older adults; 4 excluded from analysis for missing second interview; 4 lost their chat history, 2 declined chat history collection; no information about age and duration. |

|

|

| Schroeder et al., 2018 | America | Mental Health | Treatment and education | Quasi-experimental (4 weeks; 73 individuals; surveys containing OASIS and PHQ-9 scales for anxiety and depression, and 5-point Likert scale question for user satisfaction). | Seventy-three participants. Female: 65; male: 7; age: 18–63; duration: 4 weeks. |

|

|

| Sebastian & Richards, 2017 | Australia | Mental and Physical Health (Anorexia Nervosa) | Education and increased awareness | RCT (245 participants; 4 min video, variant-time ECA interaction, but same transcript length; 4-way design Mental health literacy (MHL) framework is used to assess stigma amongst participants). | Two hundred and forty-five undergraduate university students. Age: +18; no information about gender and study duration. |

|

|

| Shamekhi & Bickmore, 2018 | America | Various Chronic Conditions; Pain, Anxiety, and Depression | Treatment and coaching | RCT (Respiration) (2 × 12 min meditations; Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) used to assess mindfulness; the control group was given agent treatment without respiratory sensors). RCT (Comparison) (24 participants; 2 × 12 min meditations; the control group was shown Eckhart Tolle video; agent dialogue was modified to match the video). | Respiratory RCT had 21 participants. Age: +18; male: 38%; female: 62%; duration: 2 sessions; (12 min per session). Comparison RCT had 24 participants; Age: +18; male: 63%; female: 37%; duration: 2 sessions; (12 min per session). |

|

|

| Tielman et al., 2017 | Netherla-nds | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). | Treatment. | Quasi-experimental (4 participants; 12 sessions with a CA to create a virtual diary, then the PTSD environment was recreated in Worldbuilder. Participants started with self-assessments, and sessions are closed with a questionnaire (5 pt. Likert scale)). | Four participants. Two males were war-veterans; two females experienced childhood sexual abuse; no information about age and study duration. |

|

|

| Author, Year | Type of Communication Technology; Type of Conversational Agent | AI Methods Used | Dialogue Management | Dialogue Initiative | Input | Output | Task-Oriented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azzini et al., 2003 | Smartphone and web-based; spoken dialog system. | Speech recognition and spoken dialog system. | Finite-state | Mixed | Spoken | Spoken, written | Yes |

| Baptista et al., 2020 | Smartphone app; ECA. | Speech recognition, natural language processing. | Finite-state | System | Spoken, visual | Spoken, written, visual | Yes |

| Beaudry et al., 2019 | Text messaging platform; chatbot. | Machine learning, NLU, NLP, deep learning, speech recognition. | Finite-state | System | Written | Written | Yes |

| Bickmore et al., 2010 | Framework; ECA. | Speech recognition, synthetic voice. | Finite-state | System | Spoken, visual | Spoken, written, visual | Yes |

| Bickmore et al., 2010 | Home desktop software; animated agent and interaction dialogues. | Not reported. | Finite-state | System | Visual | Spoken, visual | Yes |

| Bott et al., 2019 | Platform; ECA. | Text-to-speech, NLU. | Frame-based | Mixed | Spoken, visual | Spoken, written, visual | Yes |

| Chaix et al., 2019 | Smartphone and web-based; chatbot. | Machine learning, NLP. | Finite-state | System | Written, visual | Written | Yes |

| Dworkin et al., 2018 | Smartphone app; Avatar-based embodied agent. | Not reported. | Finite-state | Mixed | Spoken, written, visual | Spoken, written, visual | Yes |

| Easton et al., 2019 | Web-based; avatar and chatbot. | NLP, speech recognition. | Frame-based | Mixed | Spoken, written | Spoken, written, visual | Yes |

| Greer et al., 2019 | Facebook messenger; chatbot. | Not reported. | Finite-state | System | Written | Written, visual | Yes |

| Hauser-Ulrich et al., 2019 | Smartphone app; chatbot. | Not reported. | Finite-state | System | Written | Written, visual | No |

| Inkster et al., 2018 | Smartphone app; chatbot. | Machine learning, unsupervised learning. | Finite-state | System | Written | Written, visual | Yes |

| Lobo et al., 2017 | Android app; chatbot. | Speech recognition, speech synthesis, spoken natural language, hidden Markov model, natural language Understanding, natural language dialogue system. | Frame-based | Mixed | Spoken, written | Spoken, written | Yes |

| Neerincx et al., 2019 | Platform independent app, robot and avatar. | Machine learning, deep learning, speech recognition, speech synthesis. | Finite-state | System | Visual | Spoken, written, visual | Yes |

| Rehman et al., 2020 | Android app; chatbot. | NLU, speech recognition, text to speech synthesis, neural network algorithm, machine learning, natural language processing, deep learning, spoken dialog. | Frame-based | User | Spoken, written | Spoken, written | Yes |

| Stephens et al., 2019 | SMS text messaging; chatbot. | Not reported. | Frame-based | Mixed | Written | Written | Yes |

| O’Hara et al., 2008 | Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs). | Not reported. | Finite-state | System | Written | Written | Yes |

| Philip et al., 2017 | Home desktop software; Virtual human ECA. | Speech recognition, synthetic voice. | Finite-state | System | Spoken | Spoken | Yes |

| Piau et al., 2019 | Semi-automated smartphone messaging system; chatbot. | Speech to text. | Finite-state | System | Written | Written | Yes |

| Puskar et al., 2011 | Home desktop software; Relational Agent. | NLU, facial recognition, speech dialogue system. | Frame-based | System | Written | Written | Yes |

| Richards and Caldwell, 2018 | Website; Avatar and Empathic ECA a. | Speech to text. | Finite-state | System | Visual | Written; spoken | No |

| Ryu et al., 2020 | Smartphone app; chatbot. | Speech recognition. | Frame-based | System | Visual | Written | No |

| Schroeder et al., 2018 | Smartphone app; chatbot. | Not reported. | Finite-state | System | Visual | Written | Yes |

| Sebastian & Richards, 2017 | Platform independent app; ECA. | Not reported. | Finite-state | System | Visual | Written | Yes |

| Shamekhi & Bickmore, 2018 | Home desktop software; an animated agent with spoken dialogue and sensing. | Spoken dialog system. | Frame-based | System | Respiration sensor | Spoken | Yes |

| Tielman et al., 2017 | Home desktop software; an animated agent with spoken dialogue. | Spoken dialog system. | Finite-state | System | Visual | Spoken; written | Yes |

| Dialogue management | Finite-state | The user is taken through a dialogue consisting of a sequence of pre-determined steps or states. |

| Frame-based | The user is asked questions that enable the system to fill slots in a template in order to perform a task. | |

| The dialogue flow is not pre-determined, but it depends on the content of the user’s input and the information that the system has to elicit. | ||

| Agent-based | These systems enable complex communication between the system, the user, and the application. There are many variants of agent-based systems, depending on what aspects of intelligent behavior are designed into the system. In agent-based systems, communication is viewed as the interaction between two agents, each of which is capable of reasoning its own actions and beliefs, and sometimes the actions and beliefs of the other agent. The dialogue model takes the preceding context into account, with the result that the dialogue evolves dynamically as a sequence of related steps that build on each other. | |

| Dialogue initiative | User | The user leads the conversation. |

| System | The system leads the conversation. | |

| Mixed | Both the user and the system can lead the conversation. | |

| Input modality | Spoken | The user uses spoken language to interact with the system. |

| Written | The user uses written language to interact with the system. | |

| Output modality | Spoken, Written, visual (e.g., non-verbal communication like facial expressions or body movements). | |

| Task-oriented | Yes | The system is designed for a particular task and is set up to have short conversations, in order to get the necessary information to achieve the goal (e.g., booking a consultation). |

| No | The system is not directed to the short-term achievement of a specific end-goal or task (e.g., purely conversational chatbots). | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bin Sawad, A.; Narayan, B.; Alnefaie, A.; Maqbool, A.; Mckie, I.; Smith, J.; Yuksel, B.; Puthal, D.; Prasad, M.; Kocaballi, A.B. A Systematic Review on Healthcare Artificial Intelligent Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions. Sensors 2022, 22, 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22072625

Bin Sawad A, Narayan B, Alnefaie A, Maqbool A, Mckie I, Smith J, Yuksel B, Puthal D, Prasad M, Kocaballi AB. A Systematic Review on Healthcare Artificial Intelligent Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions. Sensors. 2022; 22(7):2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22072625

Chicago/Turabian StyleBin Sawad, Abdullah, Bhuva Narayan, Ahlam Alnefaie, Ashwaq Maqbool, Indra Mckie, Jemma Smith, Berkan Yuksel, Deepak Puthal, Mukesh Prasad, and A. Baki Kocaballi. 2022. "A Systematic Review on Healthcare Artificial Intelligent Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions" Sensors 22, no. 7: 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22072625

APA StyleBin Sawad, A., Narayan, B., Alnefaie, A., Maqbool, A., Mckie, I., Smith, J., Yuksel, B., Puthal, D., Prasad, M., & Kocaballi, A. B. (2022). A Systematic Review on Healthcare Artificial Intelligent Conversational Agents for Chronic Conditions. Sensors, 22(7), 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22072625