Abstract

Building context-aware applications is an already widely researched topic. It is our belief that context awareness has the potential to supplement the Internet of Things, when a suitable methodology including supporting tools will ease the development of context-aware applications. We believe that a meta-model based approach can be key to achieving this goal. In this paper, we present our meta-model based methodology, which allows us to define and build application-specific context models and the integration of sensor data without any programming. We describe how that methodology is applied with the implementation of a relatively simple context-aware COVID-safe navigation app. The outcome showed that programmers with no experience in context-awareness were able to understand the concepts easily and were able to effectively use it after receiving a short training. Therefore, context-awareness is able to be implemented within a short amount of time. We conclude that this can also be the case for the development of other context-aware applications, which have the same context-awareness characteristics. We have also identified further optimization potential, which we will discuss at the conclusion of this article.

1. Introduction

Discussions on the development of context-aware applications, including technologies and methodologies, are not new. A lot of these discussions were carried out before the 1990s with Marc Weiser’s idea on ubiquitous computing [1] and is still ongoing. Dey [2] defined an application context-aware if: “it used context to provide relevant information and/or services to the user, where relevancy depends on the user’s task”. According to Dey [2], context is: “any information that can be used to characterize the situation of an entity”, where “an entity can be a person, place, or object that is considered relevant to the interaction between a user and an application, including the user and applications themselves”.

An example for a context-aware application is a context-aware tour guide, which provides information to their users depending on their location and/or personal preference [3]. Another example is the pre-registration of elevators in a smart building using the localization of passengers within the callable range of an elevator, which should reduce the waiting time for passengers [4]. Numerous such examples can be found in different application areas, such as health care [5], residences for the elderly [6] and industrial applications [7].

Context-aware applications aim to reduce the need for user intervention [8]. Such applications can provide an automatic context-triggered action [9] e.g., initiating an emergency call if a fall of an inhabitant living in a smart home has been detected.

With the development of the “Internet of Things”, several industries are experiencing a digital transformation, where the development and usage of a “Digital Twin” is considered a technology that can help gain competitive and economic advantage over its competitors [10]. A Digital Twin refers to the virtual copy or model of any physical entity, both of which are interconnected via exchange of data in real time. In a broader view, the virtual copy or Digital Shadow, which is updated through sensors, can be applied in context-aware applications [11]. In [12], the authors describe that future Digital Twins have to be context-aware.

Research on context-awareness has been conducted since the 1990s; the development of such applications is still very challenging and expensive. We need to simplify the development process, in order to help overcome high application overheads, social barriers associated with privacy and usability, and an imperfect understanding of the truly compelling use of context-awareness [13]. A very detailed overview on the context-awareness system engineering challenges and applied techniques is given in [14]. One of many challenges is the way context information is being handled. In order to simplify the development of context-aware applications, a separation is required on how context is acquired to how it is used. The way context information should be used in such applications is without implementing the knowledge of sensor details and their implementation [15]. According to Henricksen et al. [3], such context information can originate from four types of sources. They can be “sensed, static, user-supplied (profiled) “ or “derived”. Context-aware applications must build on such information, which may require additional interpretation to be significant for applications [16]. In reference [17], three different architectural approaches for the implementation of the context related functionality are identified: direct sensor access, middleware infrastructure, and context server. In references [18,19,20], overviews on existing context frameworks, servers, and a discussion of their features, are given. Another challenge is the methodology of building context-aware applications. The requirements elicitation process is necessary to understand the user’s needs. In reference [14] an overview of existing approaches are given. These requirements can be formally specified through different modeling approaches, e.g., the Context Modeling Language (CML) [21]. The resulting context model can then be implemented using different approaches, e.g., key-value models. An overview and discussion is given in [14,22]. Additionally, design evaluation can be applied to verify that the implementation of context-aware behavior has been carried out correctly. This can be conducted through model checking, e.g., reference [23]. All these aspects have to be included into a methodology for the development of context-aware applications. In reference [14], the desirable features for a methodology are identified. Additionally, existing methodologies and tools are identified and evaluated regarding the desirable features. As a conclusion of that evaluation, the authors state that there is a strong tool support for the design and development of context-aware applications.

Though a number of methodologies and tools exist and are well discussed in the research community, the challenge still exists. We need experiences from the application of those methodologies in real applications. Therefore, based on these discussions, we follow an inductive approach to the question of how to minimize the development overheads and simplify the implementation of context-aware applications. We have developed our methodology, which uses a meta-model based context server. A meta model defines the modeling concepts that can be used to describe concrete models [24]. We will implement applications using this methodology with different context-aware characteristics and analyze its implications. In this paper we will start that work and describe and analyze the implementation of a COVID-safe navigation app, which has relatively simple characteristics.

Our paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the related work and places our approach in its context. In Section 3 we describe the characteristics of the COVID-safe navigation app. Then, we describe the basic concepts of the context server. Section 5 then describes the methodology. In Section 6 we describe the development of the COVID-safe navigation app using the methodology and the context server. We then discuss our results.

2. Related Works

As stated in the introduction, we will follow an inductive approach towards a methodology to build context-aware applications. Therefore, papers that describe the application of a methodology for the development of concrete context-aware applications are of interest. In reference [25] we have described an initial model-based approach to build context-aware applications in a smart home environment. From then until now, we have improved the meta-model, optimized the development process, and implemented a near real-time processing context-server with an intermediate context query language. These improvements are presented in this paper.

In [19] there is an interesting investigation on how to bring context-awareness into the internet of things. The authors investigated 50 context-aware projects and tried to identify the lessons that we can learn in the IoT perspective. There are many requirements that have been identified from investigating these projects, which a context-aware IoT infrastructure should support, which also is partially supported by our context-server. What is missing for our purposes are the implications on the support to ease the development process.

There are a number of model driven development approaches, which aim to specify a context-aware application including the context conditions and the application behavior via a high-level abstraction, which then can be transferred to its implementation. The description is based on a meta-model, which can be used to describe concrete applications. One such example is presented in [26]. The modeling language, ContextUML, allows us to model the context-aware behavior of a web service. It describes the retrieval of single context attributes and when and how to automatically execute or modify the call of a web service with parameters that represent the context. In contrast to our approach context is limited to context attributes that can be relevant to the instantiation of the web services. A very complex meta-model PervML is described in reference [27]. It includes different sub-models, which can be used to describe different aspects of a pervasive application. It includes a structural model, which can be used to describe a physical location in which a service is deployed. Additionally, a user model can be used to describe context data on users and policies. These parts of the meta-model are focused on the conditions and instantiation of the services. Our approach on the contrast is focused on describing such context attributes in its broader context regarding the states of entities and their relations. This is necessary if context information should be evaluated in the context of their surrounding environment, e.g., finding paths with given context conditions. We also do not model the application logic of a context-aware application, but leave this to the programmer. We provide a context query language, which the programmer can use to access the context model.

Work on a meta-model based approach, which is only focused on the context model, can be found in reference [28]. The authors describe the motivation for a model-based approach to develop context-aware applications. Their goal is to provide a methodology that is consistent based on the meta-model through design and run time. They have published the meta-model in reference [29], but further publications on the implementation of the approach and a proof of concept cannot be found.

4. Basic Concepts of the Meta-Model Based Context Server

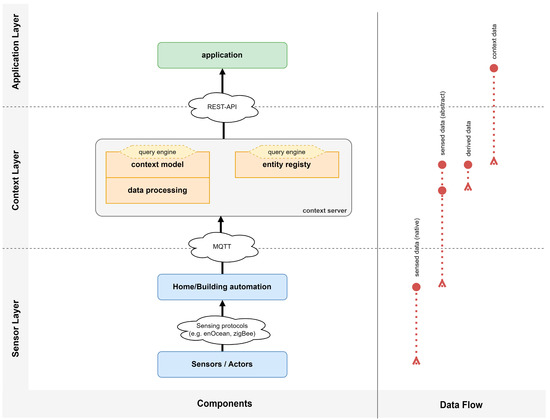

4.1. Context Server

We have implemented the HSD context server, which directly supports the meta-model as described in the next subsection. It allows us to connect sensor data to the context-model and to query the context model in near real-time. The core of the context server implements an in-memory extended graph database, where entities and relations are represented by nodes and edges. It allows the definition of node and edge types. Node types can be part of a multiple inheritance relation. A concrete graph, which represents the application specific context model, can be constructed based on the defined node and edge types.

Besides explicitly defined edges, implicit relations are also supported, which result from the application of comparison operations between edge properties. The graph database also directly supports geometric location data types and operations, which can also be part of an implicit relation.

4.2. Meta-Model

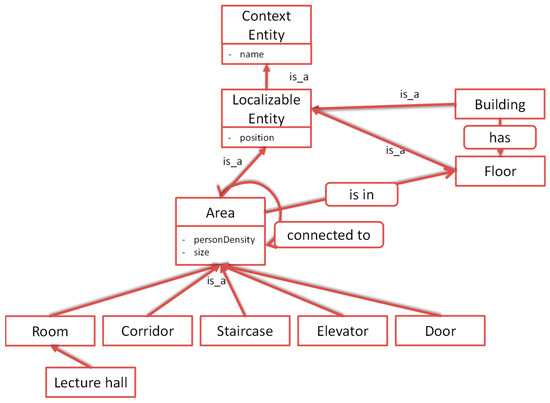

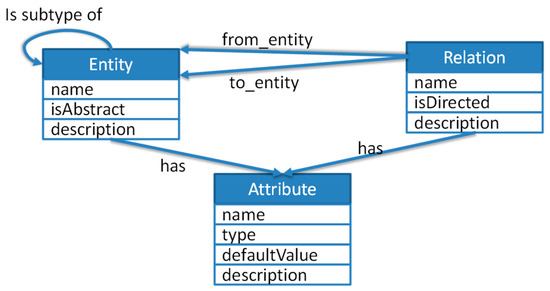

Based on a meta-model, the developer can define the application specific context model. An overview of the relevant part of the meta-model is given in the following Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Excerpt of the meta-model.

The meta-model allows us to define entity types with a set of attributes. An entity is any object in the real environment that is considered relevant for the specific context aware application. We can define abstract entity types and also a subtype-relation between entity types, where attributes are inherited from the super-types.

We can define relation types between two entity types. These relation types can be directed, meaning that the relation is only valid from the source entity type to the destination and not vice versa.

Attributes define the named properties of entities or relations and are of a defined data type, e.g., numeric. An attribute can have a default value.

All the model elements can have a description, which allows us to document the context model schema.

4.3. Location Models

The context server supports both geometric and symbolic location models. A good overview on location models can be found in reference [30]. A geometric location model is based on geometric coordinates, such as a geometric location model, implemented in the context server by the special data type ‘location-geometric’. Currently, this data type supports the definition of a rectangular cuboid with a given starting point (xstart, ystart, zstart) and an ending point (xend, yend, zend). This data type includes a distance function, which allows us to calculate the walking distance of a path, but also to execute range queries.

Additionally, the usage of a symbolic location model is supported. The meta-model allows us to define and use context entities as such symbols, e.g., the room name. Relation types can be used to define spatial relations, e.g., “containment” or “is connected”. The distance between two symbolic coordinates can be explicitly given in defined attributes of these relations.

The context server allows us to combine these different location models into a hybrid location model.

4.4. Context Query Language

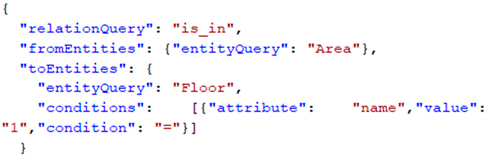

The context server has an intermediate query language, which is very close to the implementation of the context server, and it is then directly compiled into the execution engine of the server. It is less developer friendly, but currently the only way to define queries that can be directly executed. The query language allows us to search and to traverse through the context model, which is internally implemented as a graph. The query language uses the JSON-syntax. The basic elements of the language are given in the following.

In its simplest form, the query language allows querying for entities of a given type with or without attribute conditions. The following Listing 1 shows the syntax of such an entity query. In Section 6.4 concrete examples of such queries are given.

| Listing 1. Syntax of an entity query. |

| { "entityQuery": "<entity type>", "conditions": [ { "attribute": "<name>", "value": "<value>", "condition": "<operator>" }, ... ] } |

A relation query allows us to find specified relations between entities, which can be further reduced by entity queries. The following listing shows the syntax of a relation query. Relation queries can be further concatenated. Either the starting entity or the destination entity of a relation can be the start or the destination of another concatenated relation.

In order to traverse through the context model, a transitive relation query can be used. This means that if an entity “A” is related to an entity “B”, and an entity “B” is related to an entity “C”, then entity “A” is also related to entity “C”. Such a query can be used, for example, to find a path using a symbolic location model where symbolic locations are “connected” with each other.

5. Development Methodology

Our development methodology consists of five steps. These will be outlined in the following. How we applied this methodology to implement the COVID-safe navigation app is described in the next section.

Step 1 is to define the application specific context model and to implement it into the context server using the meta-model. First, the conceptual context model is defined. The entities and relations and their properties are defined which are relevant for the application. Then, the identified entities are examined regarding common properties or semantics. These may be a reason for defining super entities that can be used to organize those entities in an object-oriented manner. The conceptual context model is then implemented into the context server using an XML-description. After the description is implemented, the entity and relation types and their properties are available in the context server.

Step 2 is the instantiation of the context model. In this step, the concrete entities and relations are registered in the context server. The context server provides two kinds of interfaces for the registration. One possibility is to use a REST-interface to add, modify, and delete concrete entities and relations. As an alternative, one can use a JAVA-API. After this step, the context model is built internally in the form of an extended graph database.

The application of step 1 and step 2 in the development of the COVID-safe navigation app is described in detail in Section 6.3.

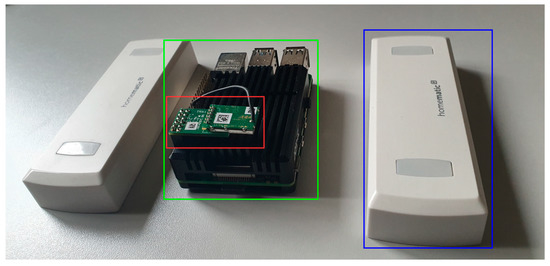

Step 3 is the assignation of the sensors to attributes of entities or relations of the model instances. This is conducted by using a configuration file. A “fingerprint” is used to associate sensor data to the properties of certain entities or relations. Incoming sensor data will then automatically update the context model. The application of this step in the project is described in Section 6.5.

After these three steps, the context server provides a digital environment model for the specific application. The following two steps will integrate the context logic into the application.

In step 4, the context model can now be queried and supervised using the context query language. The concrete queries will be defined in the next step and they can be manually tested using a web interface. The context queries for our project are described in Section 6.4.

In step 5, the application is connected to the context server using the REST-API. Through this API the application can execute context queries, and also subscribe to context change events.

7. Discussion

We have described how to apply the methodology to build fairly simple context-aware applications, such as the COVID-safe navigation app, using a meta-model based context server. We have described the basic characteristics of that app in Section 3. Based on the implementation of the COVID-safe navigation app, we have shown that a small team of students, which had no previous experience in context awareness, were able to build a context-aware application with these characteristics within a very limited time frame. The meta-model and the methodology were easy to understand and apply. At this point, we do not have a direct comparison of our approach with a manual implementation to prove that it simplifies the development of such context-aware applications. However, the student project gives some indication that this may be the case. In another student project, we implemented a digital fire brigade plan. In that project, the fire brigade is supplied with a mobile front end, which shows the structure of the building, the state of fire doors, the location of detected smoke and areas with a population density. It also calculates a suitable path from any entrance to the detected smoke area. We had the same result in that project. We assume that this will be the case for the development of any other context-aware applications with the same characteristics. Such an application could be used in an industry 4.0 scenario. The context server can be used for the identification of free transportation units nearby and the navigation of these units depending on the characteristics and state of the production environment.

However, the project also showed some shortcomings, which we have to handle in the future. The instantiation of the context-model using the Java-API was very time consuming, since each entity and relation had to be programmed manually, which can cause errors in the programming. A visual model editor could be of great help to construct and visualize the context model. Such a tool will be one of our next steps for improvement. Additionally, a tool to import building information from existing building planning software into the context model could be added.

After the university building’s structure was initially instantiated, we tested the context model manually using the path finding query, which in some cases resulted in false results, because of the wrong instantiations. It was time consuming to find potential mistakes in the model, and to correct them. A model checking tool that could be used to find and visualize mistakes would be needed. This would not only include errors in the instantiation, but also an evaluation of the calculated paths in different simulated person densities.

The implementation has also shown that the ability of the context query language to aggregate on single entity or relation properties may not be sufficient. The current implementation of the context server will always prioritize the paths with the lowest person density, regardless of the walking length of the path compared to other alternatives. This optimization is at the moment delegated to the application, but which should be provided by the context server in the future.

Non-functional features of the context-server were proved by the implementation of the application. The context server was able to cope with the context model of the application, which included 422 entities and 443 relations, which resulted from the description of the university’s building structure. The implemented in memory graph database did not have a problem with the size of the context model, but also not with executing queries that required a flexible traversal through the model graph in order to identify the possible routes, calculate the walking distances, aggregate the person density on the route and to prioritize these routes. In our runtime environment, it took around 9 ms for the context server to identify the possible paths, which typically included the description of 33 path alternatives and their aggregations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W.; methodology, M.W.; project administration, P.P.; resources, P.P.; software, M.W. and P.P.; supervision, P.P.; visualization, M.W. and P.P.; Writing—original draft, M.W. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weiser, M. The computer for the 21st Century. Sci. Am. 1991, 265, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K. Understanding and using context. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2001, 5, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, W.; Gruen, C.; Proell, B.; Retschitzegger, W.; Schauerhuber, A. Context-Awareness in Mobile Tourism Guides—A Comprehensive Survey; Rapport Technique; Johannes Kepler University: Linz, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hangli, G.; Hamada, T.; Sumitomo, T.; Koshizuka, N. PrecaElevator: Towards Zero-Waiting Time on Calling Elevator by Utilizing Context Aware Platform in Smart Building. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), Nara, Japan, 9–12 October 2018; pp. 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricon-Souf, N.; Newman, C.R. Context awareness in health care: A review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2007, 76, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroese, B.; Van Kasteren, T.; Gibson, C.; Van den Dool, T. Care: Context awareness in residences for elderly. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the International Society for Gerontechnology, Pisa, Italy, 4–6 June 2008; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger, P.; Gerhard, D. Context-awareness in industrial applications: Definition, classification and use case. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardian, B.; Indulska, J.; Henricksen, K. Balancing autonomy and user control in context-aware systems—A survey. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PERCOMW’06), Pisa, Italy, 13–17 March 2006; pp. 6–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schilit, W. A System Architecture for Context-Aware Mobile Computing. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Fuenmayor, E.; Hinchy, E.P.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Digital twin: Origin to future. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2021, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlab, N.; Braun, D.; Jung, T.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. A Tier-based Model for Realizing Context-Awareness of Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Vasteras, Sweden, 7–10 September 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hribernik, K.; Cabri, G.; Mandreoli, F.; Mentzas, G. Autonomous, context-aware, adaptive Digital Twins—State of the art and roadmap. Comput. Ind. 2021, 133, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henricksen, K.; Indulska, J. Developing context-aware pervasive computing applications: Models and approach. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2006, 2, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, U.; Wrede, J.; Clark, T. Engineering Context-Aware Systems and Applications: A survey. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 117, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K.; Abowd, G.D.; Salber, D. A conceptual framework and a toolkit for supporting the rapid prototyping of context-aware applications. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2001, 16, 97–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henricksen, K.; Indulska, J.; Rakotonirainy, A. Modeling Context Information in Pervasive Computing Systems. In Pervasive Computing, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Pervasive Computing, Zürich, Switzerland, 26–28 August 2002; Friedemann, M., Mahmoud, N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2414, pp. 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Finin, T.; Joshi, A. An ontology for context-aware pervasive computing environments. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2004, 18, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, M.; Dustdar, S.; Rosenberg, F. A survey on context-aware systems. Int. J. Ad Hoc Ubiquitous Comput. 2007, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.; Zaslavsky, A.; Christen, P.; Georgakopoulos, D. Context aware computing for the internet of things: A. survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 16, 414–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Eckert, M.; Martinez, J.F.; Rubio, G. Context aware middleware architectures: Survey and challenges. Sensors 2015, 15, 20570–20607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, T.; Henricksen, K.; Indulska, J. Automating context-aware application development. In Proceedings of the UbiComp 1st International Workshop on Advanced Context Modelling, Reasoning and Management, Nottingham, UK, 7 September 2004; pp. 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Strang, T.; Linnhoff-Popien, C. A Context Modeling Survey. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Advanced Context Modeling, Reasoning and Management, Nottingham, UK, 7 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Preuveneers, D.; Berbers, Y. Constency in context-aware behavior: A model checking approach. In Intelligent Environments 2021: Workshop, Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Intelligent Environments, Virtual Event, 21–24 June 2012; Bashir, E., Lutrek, M., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Klint, P.; Laemmel, R.; Verhoef, C. Towards an engineering discipline for grammarware. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. (TOSEM) 2005, 14, 331–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, M.; Wiedeler, M. Model-based development of context-aware applications using the MILEO-context server. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops, Lugano, Switzerland, 19–23 March 2012; pp. 613–618. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Q.Z.; Benatallah, B. ContextUML: A UML-based modeling language for model-driven development of context-aware web services. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mobile Business (ICMB’05), NW Washington, DC, USA, 11–13 July 2005; pp. 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Serral, E.; Valderas, P.; Pelechano, V. Towards the model driven development of context-aware pervasive systems. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2010, 6, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouadi, I.; Djemaa, R.B.; Abdallah, H.B. Approach to Model-Based Development of Context-Aware Application. J. Comput. Commun. 2015, 3, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouadi, I.; Djemaa, R.B.; Abdallah, H.B. A generic metamodel for context-aware applications. In Progress in Systems Engineering, Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Conference on Systems Engineering, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19–21 August 2014; Selvaraj, H., Zydek, D., Chmaj, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C.; Dürr, F. On location models for ubiquitous computing. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2005, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).