Sign Language Recognition Method Based on Palm Definition Model and Multiple Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Problem Description and Proposed Solution

3.1. Problem Description

- Ω HA ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω HA/OH ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω HA/RLH ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω HA/TF ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω HA/TN ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω NZ ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω NRLSH ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

- Ω W ψ PTFS↔ ML/DULRS

3.2. Proposed Solution

3.2.1. Get Image

- (1)

- Starting the camera

- (2)

- Clicking on the screen

- (3)

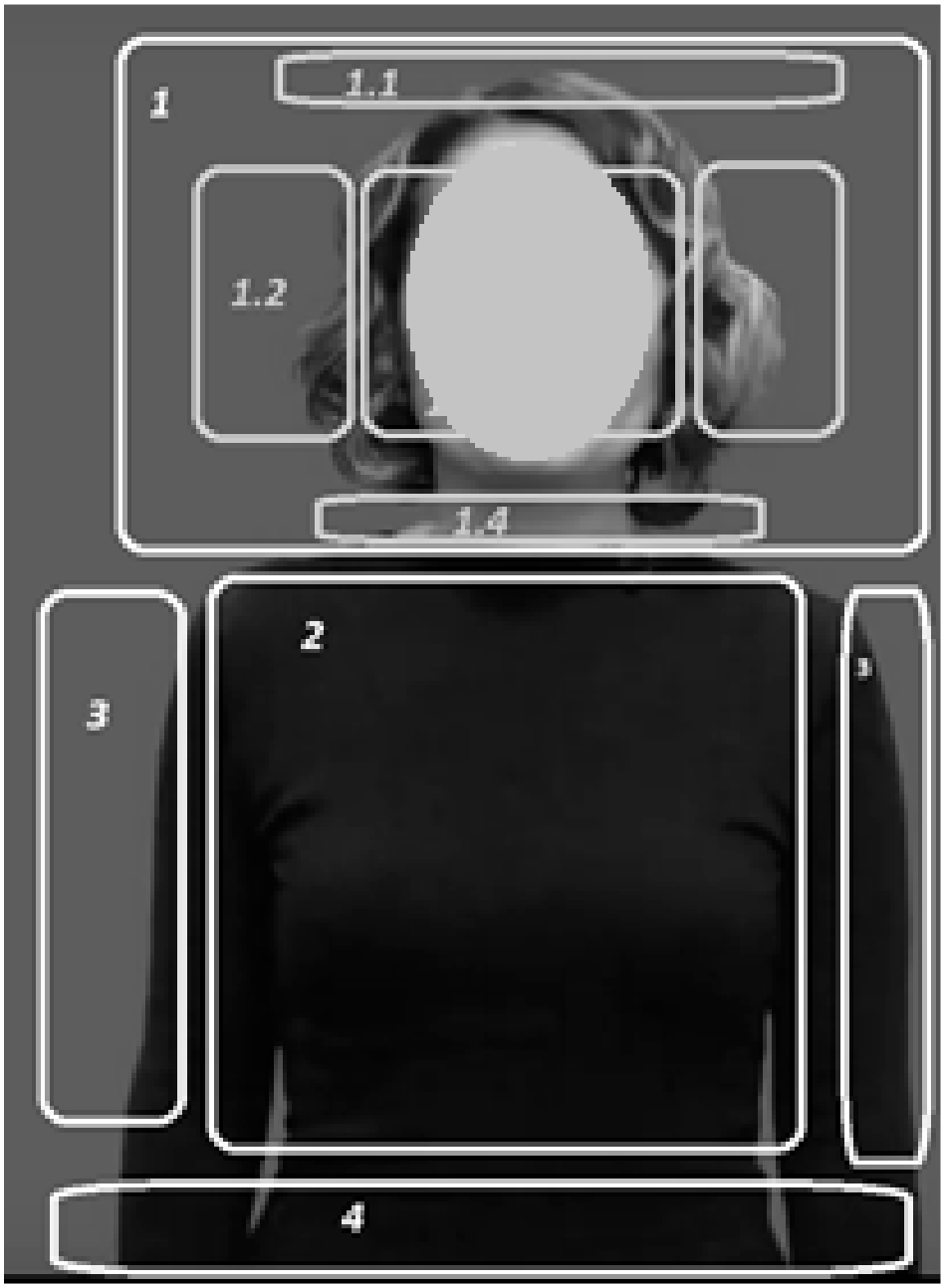

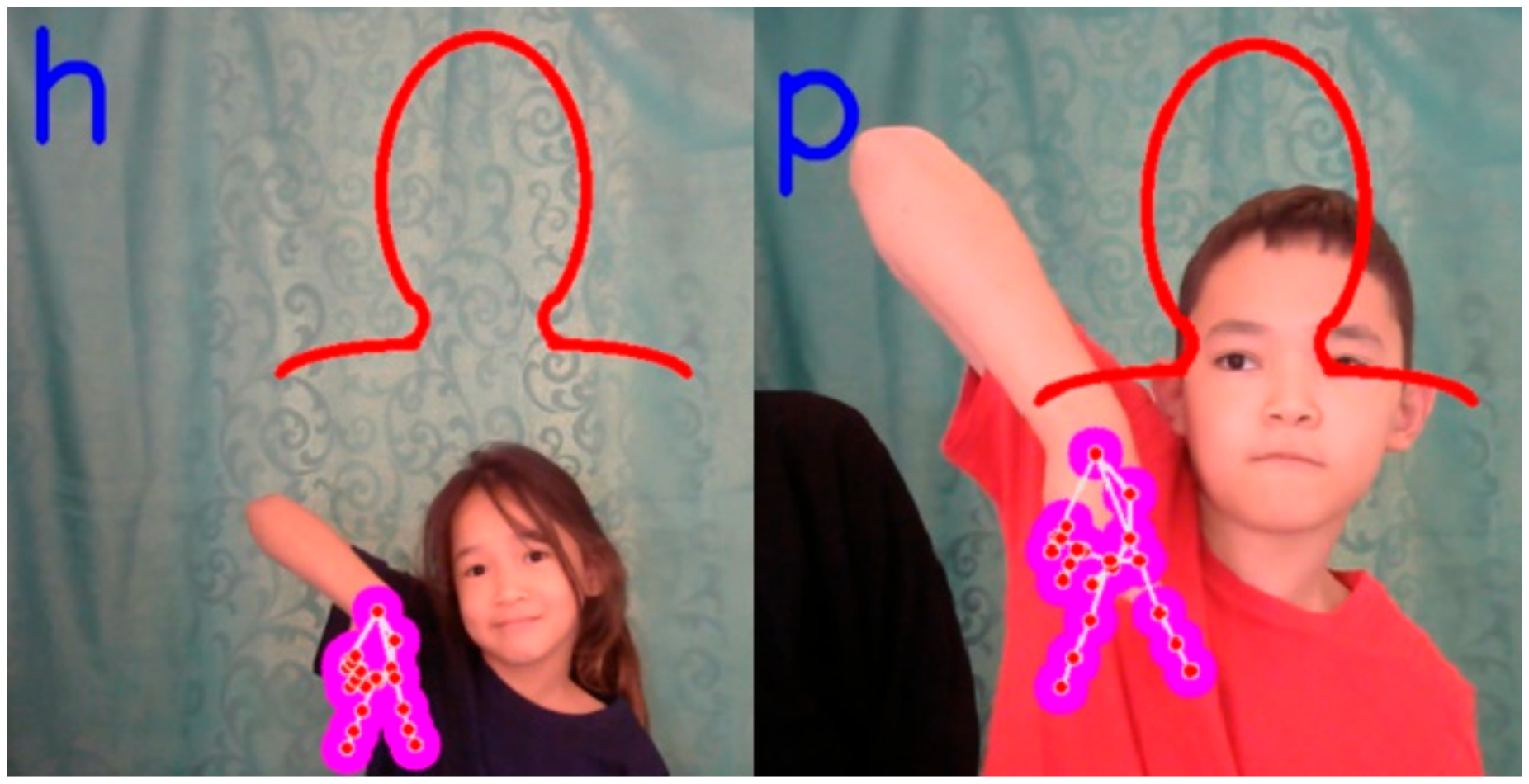

- The layout of the human upper body appears (Figure 8)

- (4)

- Adjusting the layout

- (5)

- Starting recording

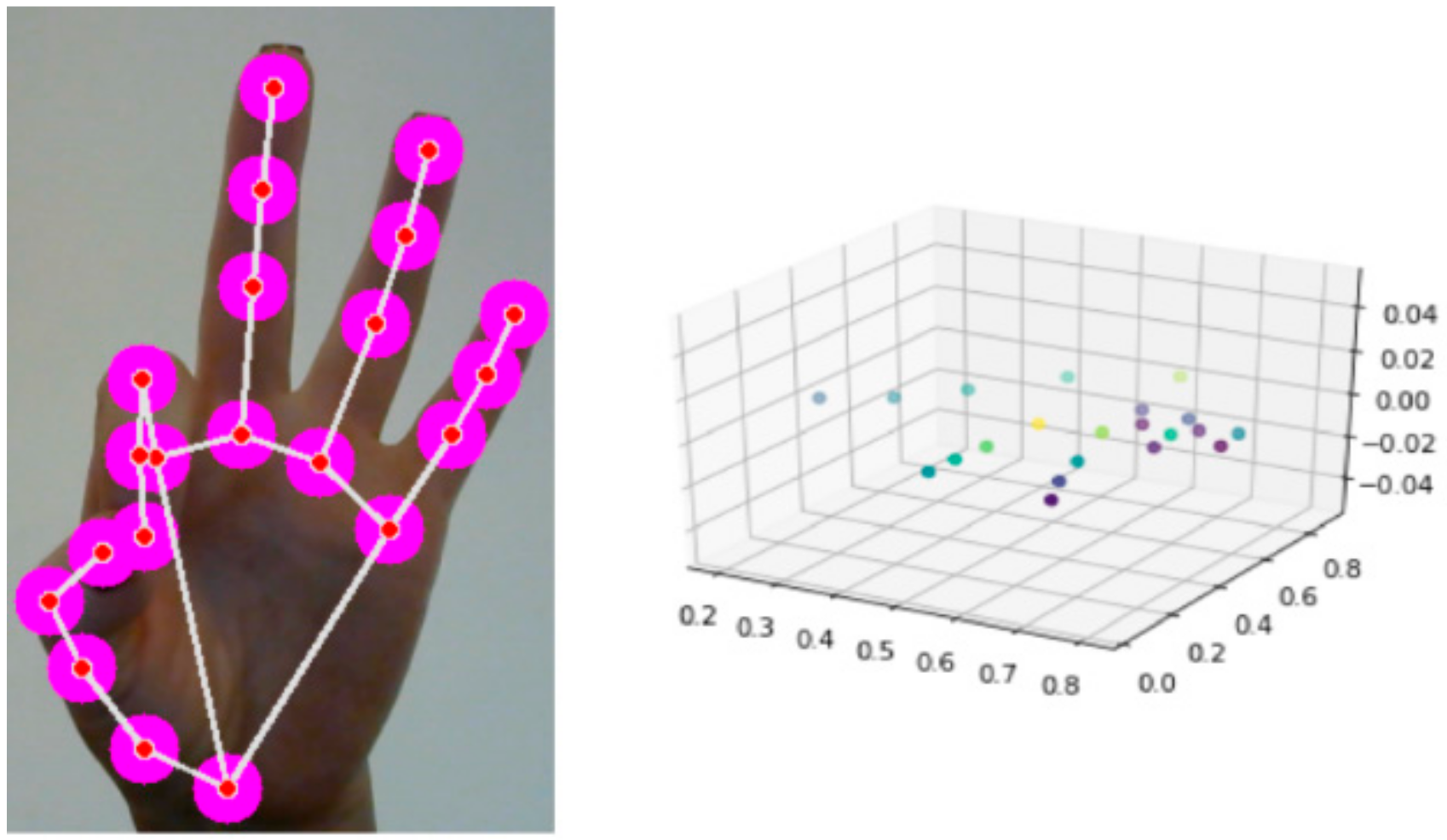

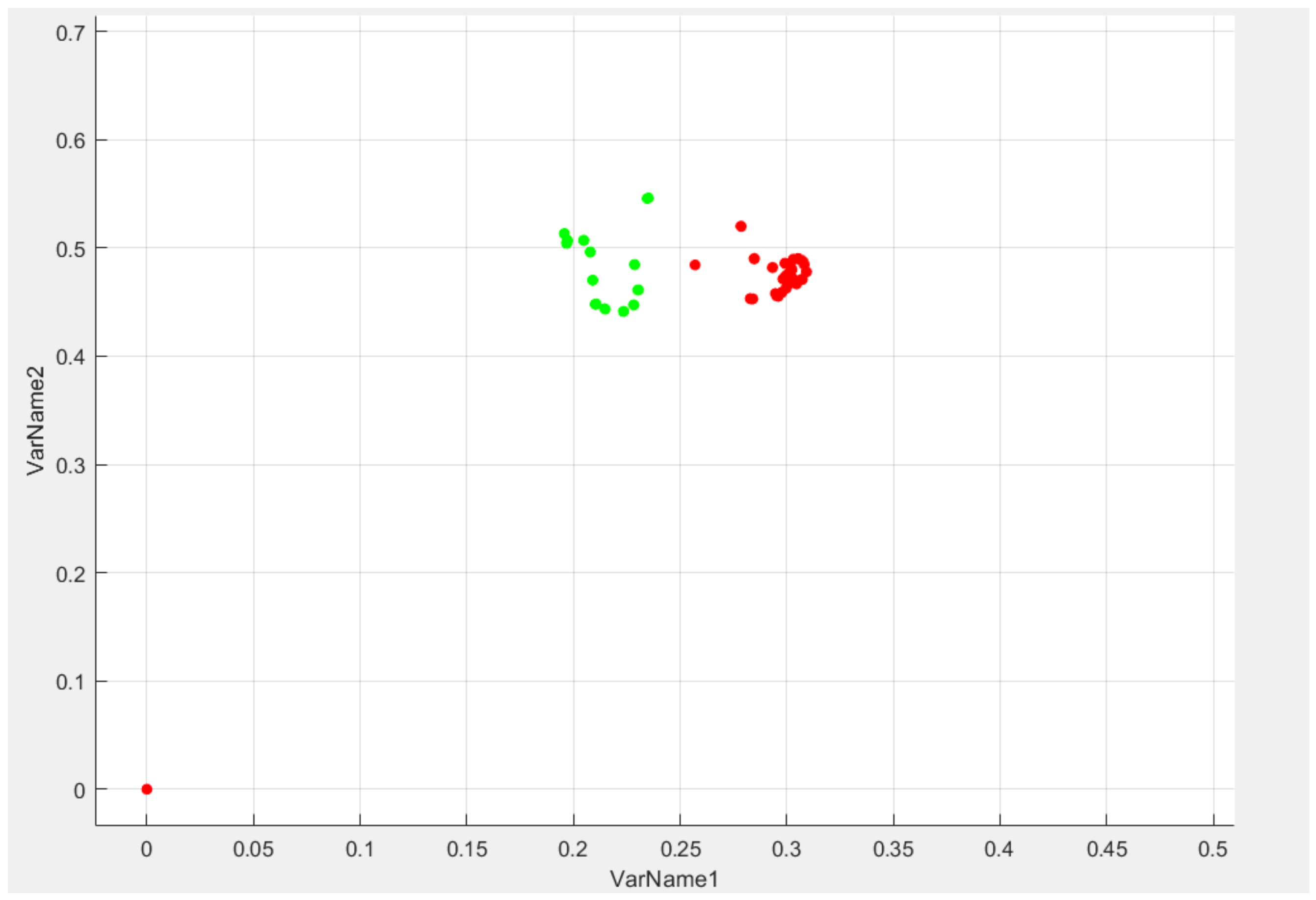

3.2.2. Get Data

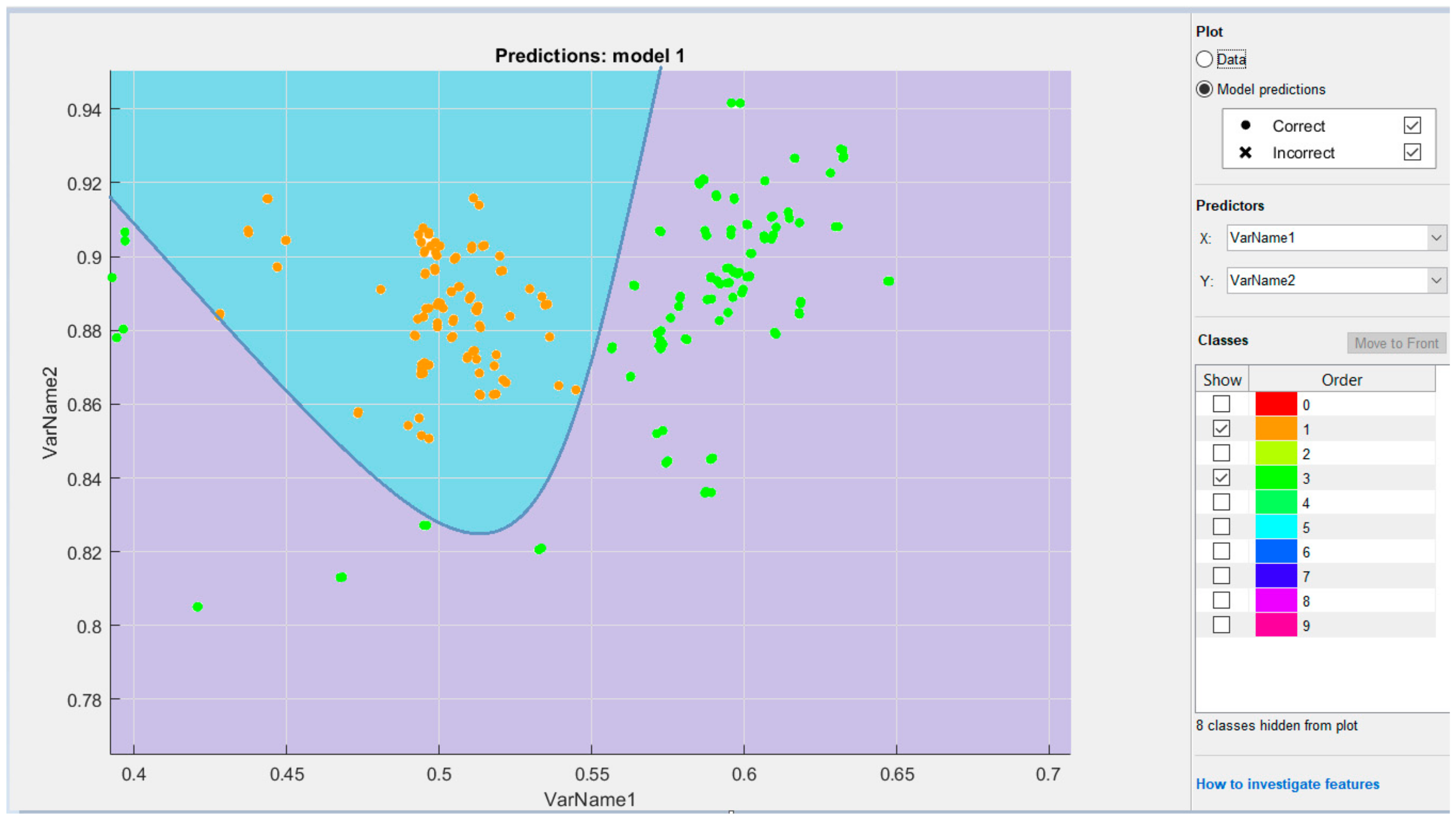

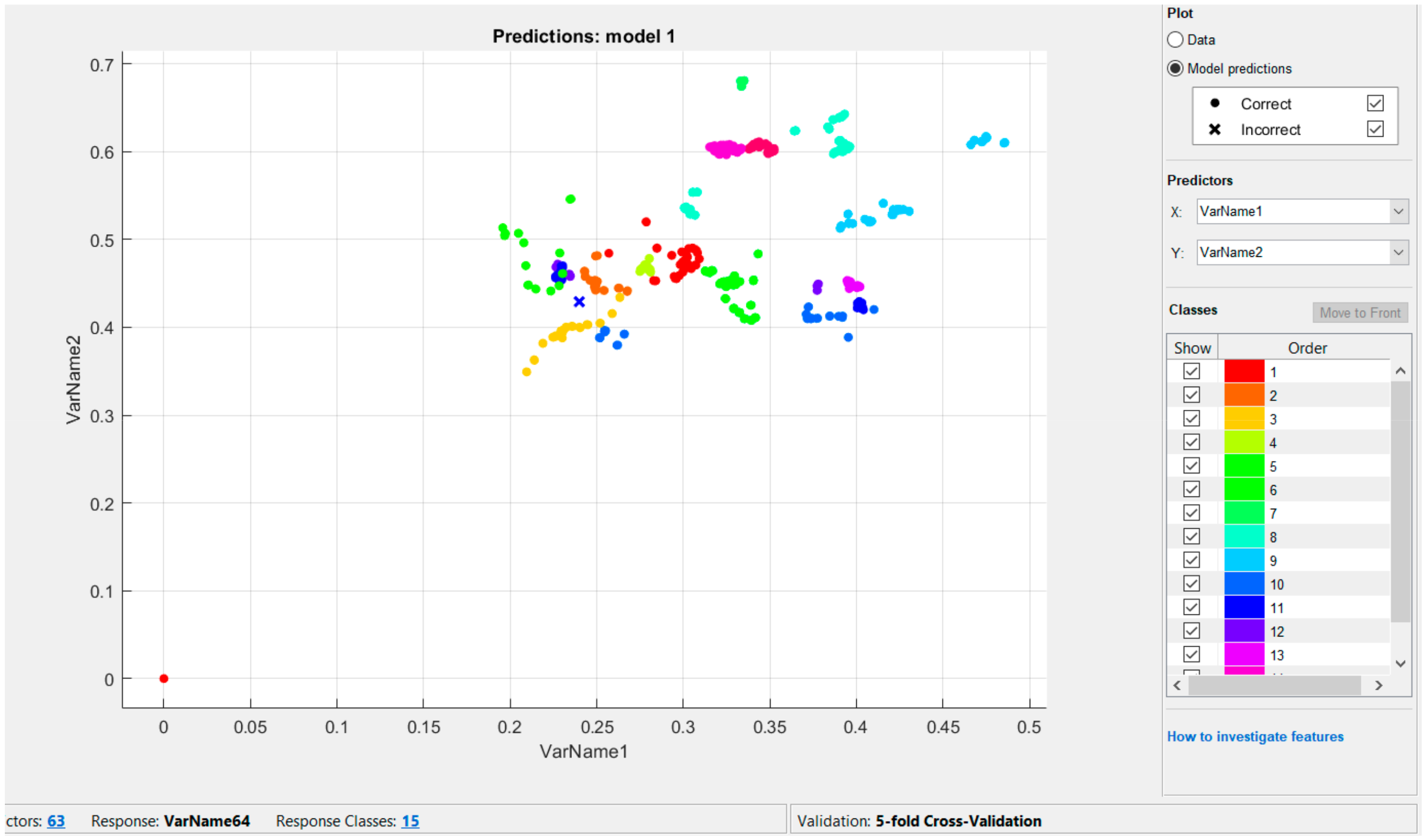

3.2.3. Get Train and Get Classification

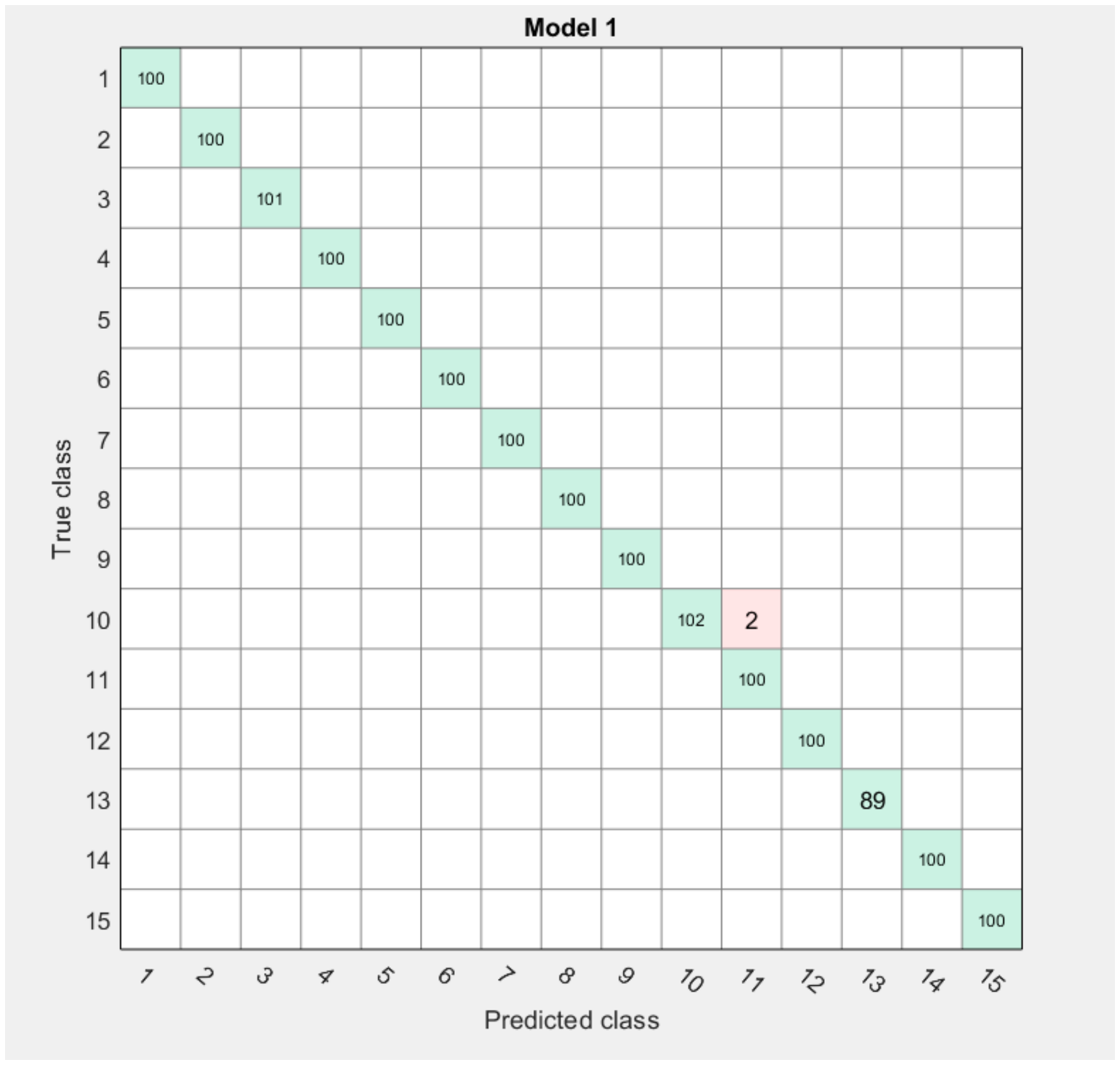

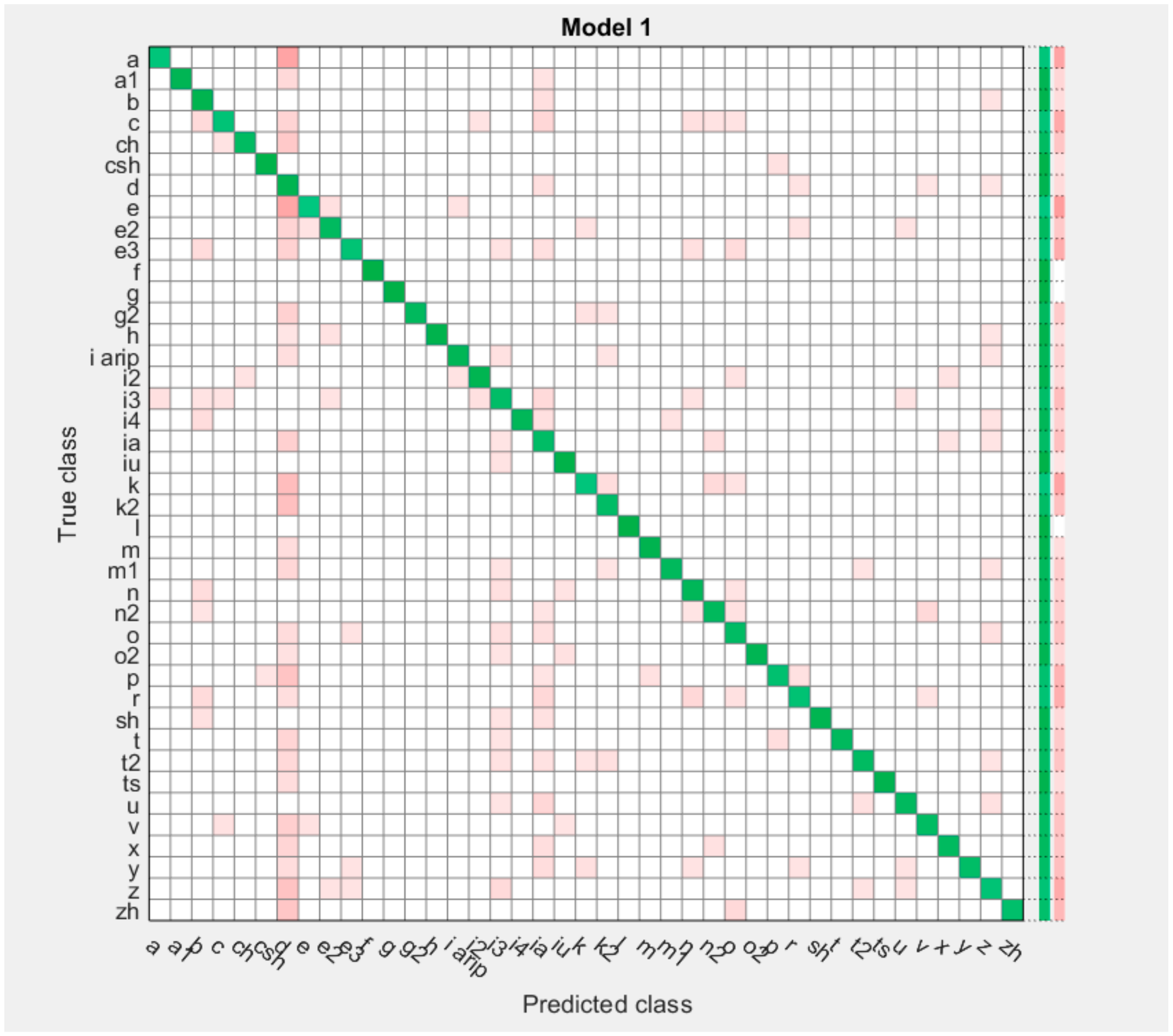

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Deafness and Hearing Loss. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Education”. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z070000319_ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- The Concept of Development of Inclusive Education in Kazakhstan. Available online: https://legalacts.egov.kz/application/downloadconceptfile?id=2506747 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Amangeldy, N.; Kudubayeva, S.A.; Tursynova, N.A.; Baymakhanova, A.; Yerbolatova, A.; Abdieva, S. Comparative analysis on the form of demonstration words of kazakh sign language with other sign languages. TURKLANG 2022, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Gani, E.; Kika, A. Albanian Sign Language (AlbSL) Number Recognition from Both Hand’s Gestures Acqu4red by Kinect Sensors. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Mittal, A.; Singh, S.; Awatramani, V. Hand Gesture Recognition using Image Processing and Feature Extraction Techniques. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 173, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.S.A.; Kousar, N.; Abdullah, T.; Ahmed, M.; Rasheed, F.; Awais, M. Pakistan Sign Language Detection using PCA and KNN. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Tavade, C.M. Performance analysis and high recognition rate of automated hand gesture recognition though GMM and SVM-KNN classifiers. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 7712–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagalkar, R.M.; Gumaste, S.V. Mobile Application Based Translation of Sign Language to Text Description in Kannada Language. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2018, 12, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; He, G. Gesture Recognition with Multiple Spatial Feature Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on Machinery, Materials and Computing Technology, Changsha, China, 18–20 March 2016; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Chen, X.; Cao, S.; Zhang, X. Random Forest-Based Recognition of Isolated Sign Language Subwords Using Data from Accelerometers and Surface Electromyographic Sensors. Sensors 2016, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenshimov, C.; Buribayev, Z.; Amirgaliyev, Y.; Ataniyazova, A.; Aitimov, A. Sign language dactyl recognition based on machine learning algorithms. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2021, 4, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, O.; Zargaran, S.; Ney, H.; Bowden, R. Deep Sign: Enabling Robust Statistical Continuous Sign Language Recognition via Hybrid CNN-HMMs. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2018, 126, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, O.; Zargaran, S.; Ney, H.; Bowden, R. Deep Sign: Hybrid CNN-HMM for Continuous Sign Language Recognition. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2016, York, UK, 19–22 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, H.; Duggal, A.; Uppara, S. Hand Motion Analysis using CNN. Int. J. Soft Comput. Eng. 2020, 9, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendarkar, D.S.; Somase, P.A.; Rebari, P.K.; Paturkar, R.R.; Khan, A.M. Web Based Recognition and Translation of American Sign Language with CNN and RNN. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2021, 17, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Islam, R.; Shin, J. Non-Touch Sign Word Recognition Based on Dynamic Hand Gesture Using Hybrid Segmentation and CNN Feature Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafis, A.F.; Suciati, N. Sign Language Recognition on Video Data Based on Graph Convolutional Network. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2021, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Adithya, V.; Rajesh, R. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network Approach for Static Hand Gesture Recognition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.; Jain, D.; Sachdeva, D.; Garg, A.; Rajput, C. Convolutional Neural Network Based American Sign Language Static Hand Gesture Recognition. Int. J. Ambient Comput. Intell. 2019, 10, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Shin, J.; Yun, K.S. Hand Gesture-based Sign Alphabet Recognition and Sentence Interpretation using a Convolutional Neural Network. Ann. Emerg. Technol. Comput. 2020, 4, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastwesy, M.R.M.; Elshennawy, N.M.; Saidahmed, M.T.F. Deep Learning Sign Language Recognition System Based on Wi-Fi CSI. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2020, 12, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Chang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Multi-Information Spatial–Temporal LSTM Fusion Continuous Sign Language Neural Machine Translation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 216718–216728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, B.; Adhikary, A.; Soheli, S.J. Sign Language Digit Recognition Using Different Convolutional Neural Network Model. Asian J. Res. Comput. Sci. 2020, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai-Kumar, S.; Sundara-Krishna, Y.K.; Tumuluru, P.; Ravi-Kiran, P. Design and Development of a Sign Language Gesture Recognition using Open CV. Int. J. Adv. Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 9, 8504–8508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.Q.; Lv, J.; Islam, S. A Deep Learning-Based End-to-End Composite System for Hand Detection and Gesture Recognition. Sensors 2019, 19, 5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khari, M.; Garg, A.K.; Gonzalez-Crespo, R.; Verdu, E. Gesture Recognition of RGB and RGB-D Static Images Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2019, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ding, R.; Ren, W.; Shu, J.; Jin, A. Gesture Recognition of Somatosensory Interactive Acupoint Massage Based on Image Feature Deep Learning Model. Trait. Signal 2021, 38, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Giachetti, A.; Soso, S.; Pintani, D.; D’Eusanio, A.; Pini, S.; Borghi, G.; Simoni, A.; Vezzani, R.; Cucchiara, R.; et al. SHREC 2021: Skeleton-based hand gesture recognition in the wild. Comput. Graph. 2021, 99, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Tayade, A. Sign Language to Text and Speech Translation in Real Time Using Convolutional Neural Network. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2021, 8, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gomase, K.; Dhanawade, A.; Gurav, P.; Lokare, S. Sign Language Recognition using Mediapipe. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Alvin, A.; Husna-Shabrina, N.; Ryo, A.; Christian, E. Hand Gesture Detection for American Sign Language using K-Nearest Neighbor with Mediapipe. Ultim. Comput. J. Sist. Komput. 2021, 13, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bandyopadhyay, N.; Chakraverty, P.; Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, Z.; Ghosh, S. Indian Sign Language Classification (ISL) using Machine Learning. Am. J. Electron. Commun. 2021, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Meng, W.; Li, H.; Cui, X. Multimodal Spatiotemporal Networks for Sign Language Recognition. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 180270–180280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Jin, H.; Tan, W.-T.; Nahrstedt, K. SKEPRID. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 2018, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, H.; El-Alfy, E.-S. Towards Hybrid Multimodal Manual and Non-Manual Arabic Sign Language Recognition: mArSL Database and Pilot Study. Electronics 2021, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagirov, I.; Ivanko, D.; Ryumin, D.; Axyonov, A.; Karpov, A. TheRuSLan: Database of Russian sign language. In Proceedings of the LREC 2020—12th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Conference Proceedings, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ryumin, D.; Kagirov, I.; Ivanko, D.; Axyonov, A.; Karpov, A.A. Automatic detection and recognition of 3d manual gestures for human-machine interaction. ISPRS Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W12, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimskis, L.S. We Study Sign Language; Academia Publishing Center: Moscow, Russia, 2002; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva, G.L. Signed speech. In Dactylology; Vlados: Moscow, Russia, 2000; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Kudubayeva, S.; Amangeldy, N.; Sundetbayeva, A.; Sarinova, A. The use of correlation analysis in the algorithm of dynamic gestures recognition in video sequence. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Engineering and MIS, Pahang, Malaysia, 6–8 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggio, G.; Cavallo, P.; Ricci, M.; Errico, V.; Zea, J.; Benalcázar, M. Sign Language Recognition Using Wearable Electronics: Implementing k-Nearest Neighbors with Dynamic Time Warping and Convolutional Neural Network Algorithms. Sensors 2020, 20, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Li, X.-Y.; Zhu, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qian, J.; Yang, P. SignSpeaker: A Real-time, High-Precision SmartWatch-based Sign Language Translator. Proceeding of the MobiCom’19: The 25th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, Los Cabos, Mexico, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Gowda, M. Finger Gesture Tracking for Interactive Applications. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Yang, J.; Qu, Y.; Liu, W.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, D. Research on Gesture Recognition Technology of Data Glove Based on Joint Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Mechanical, Electronic, Control and Automation Engineering, Qingdao, China, 30–31 March 2018; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairagi, V.K. Gloves based hand gesture recognition using indian sign language. Int. J. Latest Trends Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Chen, S.-W.; Pao, Y.-P.; Huang, M.-Z.; Chan, S.-W.; Lin, Z.-H. A smart glove with integrated triboelectric nanogenerator for self-powered gesture recognition and language expression. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummadi, C.K.; Leo, F.P.P.; Verma, K.D.; Kasireddy, S.; Scholl, P.M.; Kempfle, J.; van Laerhoven, K. Real-time and embedded detection of hand gestures with an IMU-based glove. Informatics 2018, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://pypi.org/project/mediapipe/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

| Localization | Ω | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | in_the_head_area | HA |

| 1.1 | over_the_head | HA/OH |

| 1.2 | right_left_of_the_head | HA/RLH |

| 1.3 | touching_face | HA/TF |

| 1.4 | touches_the_neck | HA/TN |

| 2 | neutral_zone | NZ |

| 3 | near_the_right_shoulder | NRLSH |

| 4 | at_the_waist | W |

| Palm Orientation | ψ | |

| 1 | palm_look_right_or_left | PLRLUD |

| 2 | palm_looks_to_from_speaker | PTFS |

| Direction of Movement | ↔ | |

| 1 | from_to_the_speaker | TFS |

| 2 | down_up_ward_Left_right_movement | DULRS |

| 3 | circular_movement | CM |

| 4 | Motionless | ML |

| Types | K | |

| 1 | one-handed | 1H |

| 2 | two-handed | 2H |

| 2.1 | do not intersect- | NTINT |

| 2.2 | Intersect | INT |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amangeldy, N.; Kudubayeva, S.; Kassymova, A.; Karipzhanova, A.; Razakhova, B.; Kuralov, S. Sign Language Recognition Method Based on Palm Definition Model and Multiple Classification. Sensors 2022, 22, 6621. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22176621

Amangeldy N, Kudubayeva S, Kassymova A, Karipzhanova A, Razakhova B, Kuralov S. Sign Language Recognition Method Based on Palm Definition Model and Multiple Classification. Sensors. 2022; 22(17):6621. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22176621

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmangeldy, Nurzada, Saule Kudubayeva, Akmaral Kassymova, Ardak Karipzhanova, Bibigul Razakhova, and Serikbay Kuralov. 2022. "Sign Language Recognition Method Based on Palm Definition Model and Multiple Classification" Sensors 22, no. 17: 6621. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22176621

APA StyleAmangeldy, N., Kudubayeva, S., Kassymova, A., Karipzhanova, A., Razakhova, B., & Kuralov, S. (2022). Sign Language Recognition Method Based on Palm Definition Model and Multiple Classification. Sensors, 22(17), 6621. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22176621