On the Security and Privacy Challenges of Virtual Assistants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

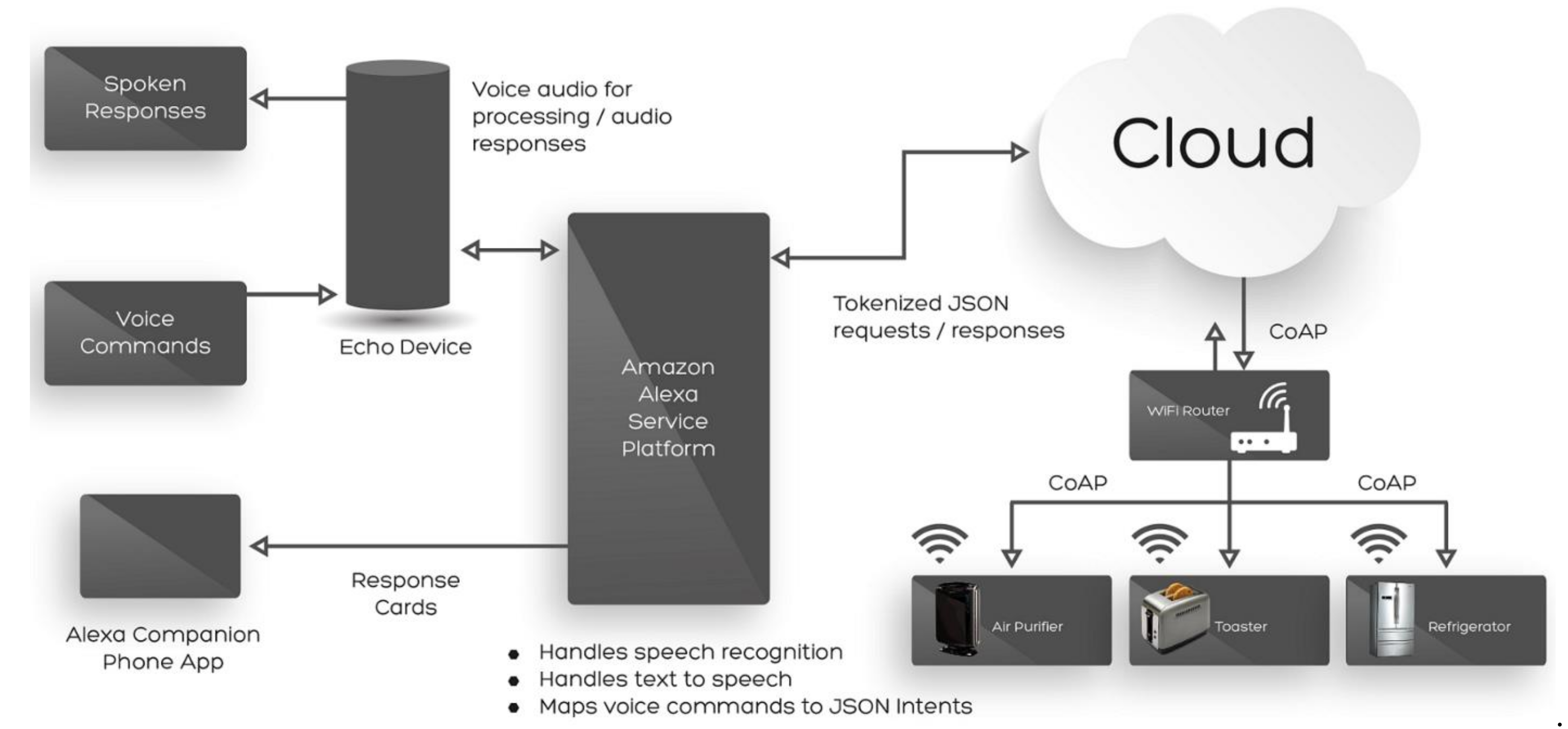

- The VA client—the ‘Echo Device’ in the diagram—is always listening for a spoken ‘wake word’; only when this is heard does any recording take place.

- The recording of the user’s request is sent to Amazon’s service platform where the speech is turned into text by speech recognition, and natural language processing is used to translate that text into machine-readable instructions.

- The recording and its text translation are sent to cloud storage, where they are kept.

- The service platform generates a voice recording response which is played to the user via a loudspeaker in the VA client. The request might activate a ‘skill’—a software extension—to play music via streaming service Spotify, for example.

- Further skills offer integration with IoT devices around the home; these can be controlled by messages sent from the service platform, via the Cloud.

- A companion smartphone app can see responses sent by the service platform; some smartphones can also act like a fully-featured client.

1.2. Prior Research and Contribution

1.3. Research Goals

2. Research Methodology

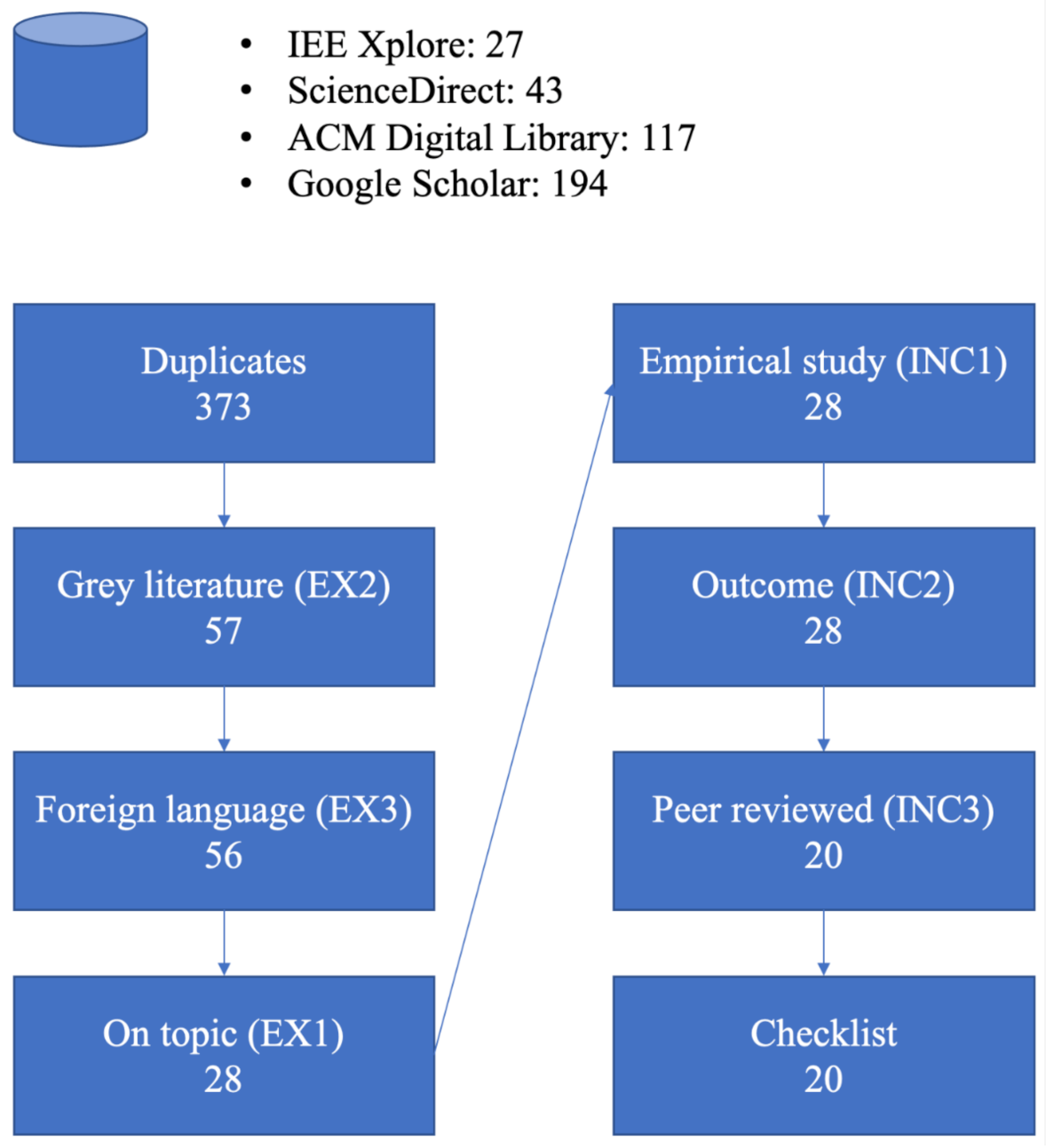

2.1. Selection of Primary Studies

- IEEE Xplore Library

- ScienceDirect

- ACM Digital Library

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Results Selection

- IEEE Xplore: 27

- ScienceDirect: 43

- ACM Digital Library: 117

- Google Scholar: 194

- Does the study clearly show the purpose of the research?

- Does the study adequately describe the background of the research and place it in context?

- Does the study present a research methodology?

- Does the study show results?

- Does the study describe a conclusion, placing the results in context?

- Does the study recommend improvements or further works?

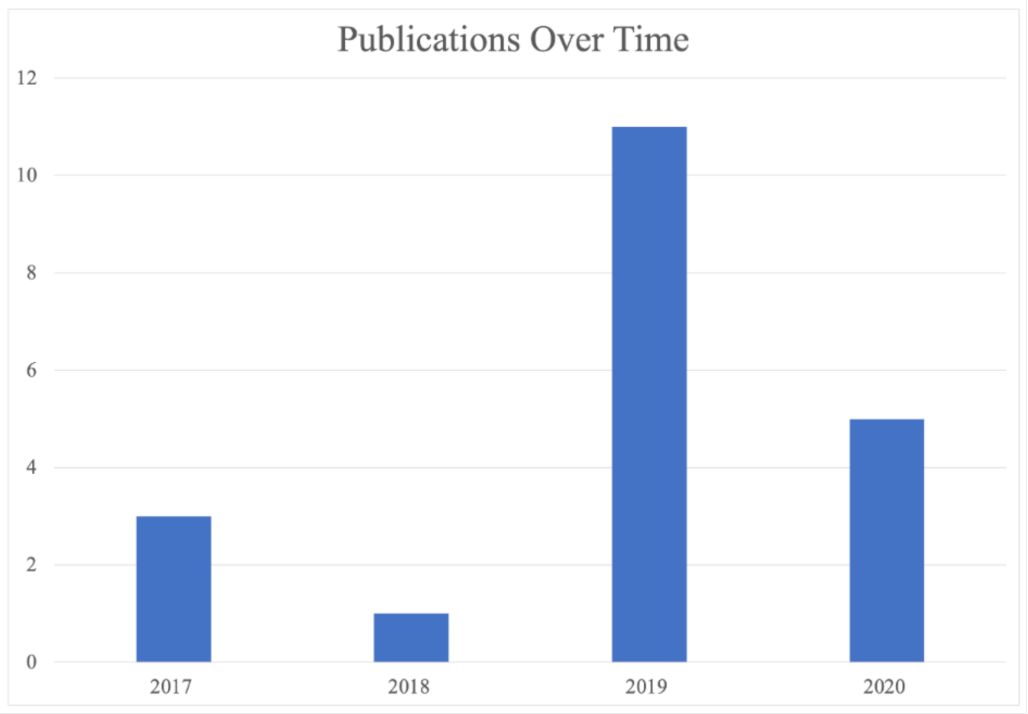

2.4. Publications over Time

3. Findings

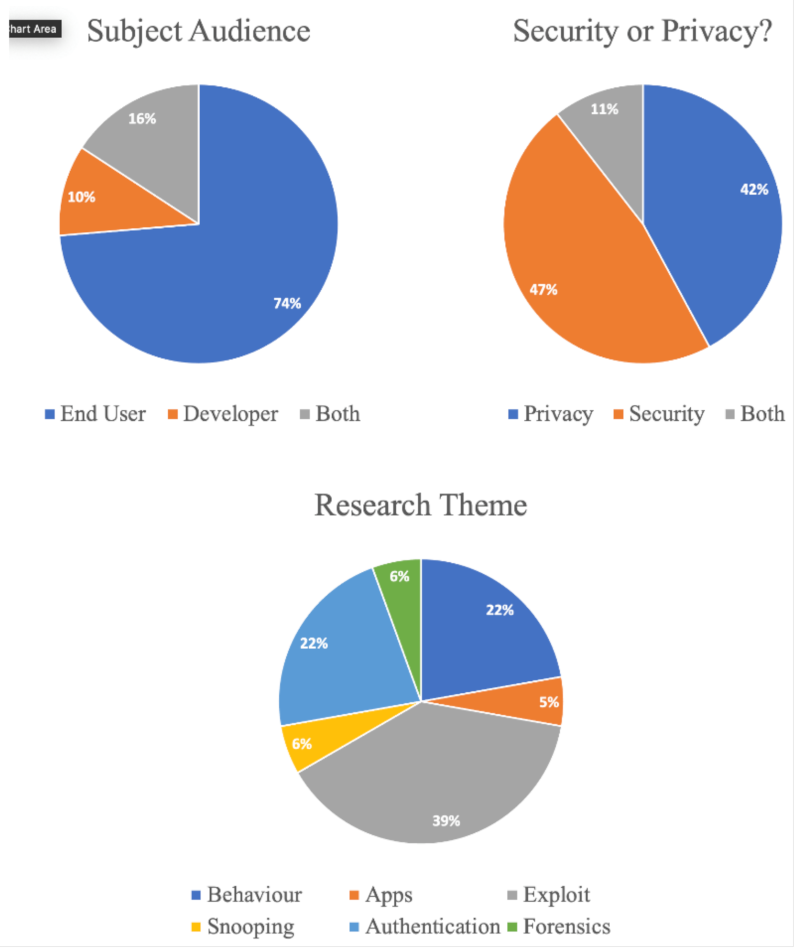

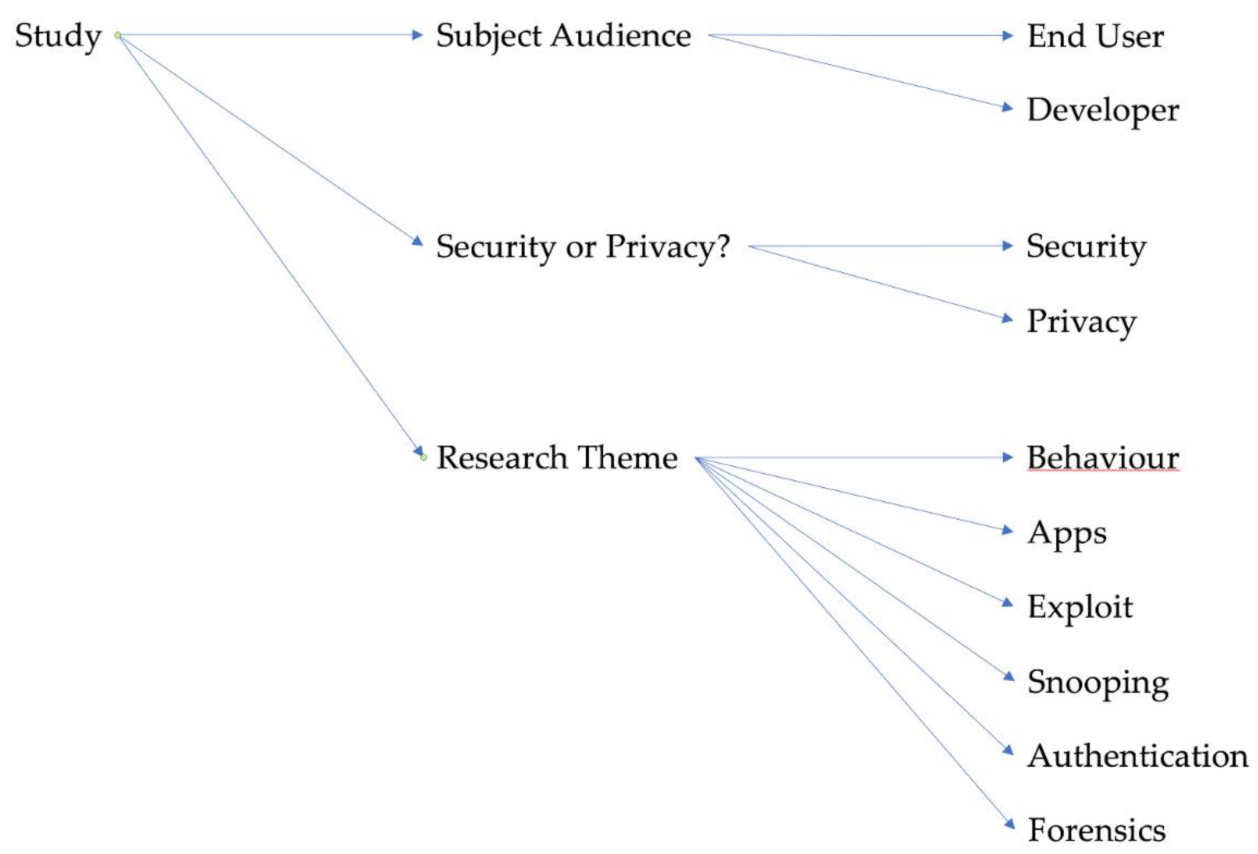

3.1. Category 1: Subject Audience

- End-user—a person who uses the VA in everyday life. This person may not have the technical knowledge and may be thought of as a ‘customer’ of the company whose VA they have adopted.

- Developer—one who writes software extensions, known as ‘skills’ (Amazon) and ‘apps’ (Google). These extensions are made available to the end-user via online marketplaces.

3.2. Category 2: Security or Privacy?

3.3. Category 3: Research Theme

- Behaviour—the reviewed study looks at how users perceive selected aspects of VAs, and factors influencing the adoption of VAs. All except one of the behavioural studies were carried out on a control group of users [11].

- Apps—the paper focuses on the development of software extensions and associated security implications.

- Exploit—the reviewed paper looks at malicious security attacks (hacking, malware) where a VA is the target of the threat actor.

- Snooping—the study is concerned with unauthorised listening, where the uninvited listening is being carried out by the device itself, as opposed to ‘Exploit’, where said listening is performed by a malicious threat actor.

- Authentication—the study looks at ways in which a user might authenticate to the device to ensure the VA knows whom it is interacting with.

- Forensics—the study looks at ways in which digital forensic artefacts can be retrieved from the device and its associated cloud services, for the purposes of a criminal investigation.

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ 1: What Are the Emerging Security and Privacy Concerns Surrounding the Use of VAs?

4.1.1. Key Findings

- Personally identifiable information can be extracted from an unsecured VA with ease.

- The GDPR appears to be of limited help in safeguarding users in its current form.

4.1.2. Discussion

4.2. RQ2: To What Degree Do Users’ Concerns Surrounding the Privacy and Security Aspects of VAs Affect Their Choice of VA and Their Behaviour around the Device?

4.2.1. Key Findings

- Rationalising of security and privacy concerns is more prevalent among those who choose to use a VA; those who don’t use one cite privacy and trust issues as factors affecting their decision.

- Conversely, amongst those who do choose to use a VA, privacy is the main factor in the acceptance of a particular model.

- ‘Unwanted’ recordings—those made by the VA without the user uttering the wake word—occur in significant numbers.

- Children see no difference between a connected toy and a VA designed for adult use.

4.2.2. Discussion

4.3. RQ3: What Are the Security and Privacy Concerns Affecting First-Party and Third-Party Application Development for VA Software?

4.3.1. Key Findings

- The processes that check third-party extensions submitted to the app stores of both Amazon and Google do a demonstrably poor job of ensuring that the apps properly authenticate from the third-party server to the Alexa/Google cloud.

- Each of the user authentication methods do go some way to mitigating the voice/replay attacks outlined in the findings of RQ1.

4.3.2. Discussion

5. Open Research Challenges and Future Directions

5.1. GDPR and the Extent of Its Protections

5.2. Forensics

5.3. Voice Authentication without External Device

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoy, M.B. Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and More: An Introduction to Voice Assistants. Med Ref. Serv. Q. 2018, 37, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Report: Smart Speaker Adoption in US Reaches 66M Units, with Amazon Leading. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/05/report-smart-speaker-adoption-in-u-s-reaches-66m-units-with-amazon-leading/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Wolfson, S. Amazon’s Alexa Recorded Private Conversation and Sent It to Random Contact. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/may/24/amazon-alexa-recorded-conversation (accessed on 24 May 2018).

- Cook, J. Amazon employees listen in to thousands of customer Alexa recordings. 2019. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2019/04/11/amazon-employees-listen-thousands-customer-alexa-recordings/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Chung, H.; Park, J.; Lee, S. Digital forensic approaches for Amazon Alexa ecosystem. Digit. Investig. 2017, 22, S15–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolias, C.; Kambourakis, G.; Stavrou, A.; Voas, J. DDoS in the IoT: Mirai and Other Botnets. Computer 2017, 50, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.; Quesada, L.; Guerrero, L.A. Alexa vs. Siri vs. Cortana vs. Google Assistant: A Comparison of Speech-Based Natural User Interfaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–21 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siebra, C.; Correia, W.; Penha, M.; Macedo, J.; Quintino, J.; Anjos, M.; Florentin, F.; da Silva, F.Q.B.; Santos, A.L.M. Virtual assistants for mobile interaction: A review from the accessibility perspective. In Proceedings of the 30th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction, Melbourne, Australia, 4–7 December 2018; pp. 568–571. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon Alexa Integrated with IoT Ecosystem Service. Available online: https://www.faststreamtech.com/blog/amazon-alexa-integrated-with-iot-ecosystem-service/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Mun, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y. A smart speaker performance measurement tool. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, SAC ’20, Brno, Czech Republic, 30 March–3 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burbach, L.; Halbach, P.; Plettenberg, N.; Nakayama, J.; Ziefle, M.; Valdez, A.C. “Hey, Siri”, “Ok, Google”, “Alexa”. In Proceedings of the Acceptance-Relevant Factors of Virtual Voice-Assistants, Aachen, Germany, 23–26 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, M.; Palmer, W. Alexa, are you listening to me? An analysis of Alexa voice service network traffic. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2019, 23, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.D.B.; Gomes, M.M.; da Costa, C.A.; Righi, R.D.R.; Barbosa, J.L.V.; Pessin, G.; De Doncker, G.; Federizzi, G. Intelligent personal assistants: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 147, 113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, C. Examining the Use of Voice Assistants: A Value-Focused Thinking Approach; Association for Information Systems. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2019/human_computer_interact/human_computer_interact/20/ (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Zhang, N.; Mi, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Qian, F. Dangerous Skills: Understanding and Mitigating Security Risks of Voice-Controlled Third-Party Functions on Virtual Personal Assistant Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Paccagnella, R.; Murley, P.; Hennenfent, E.; Mason, J.; Bates, A.; Bailey, M. Emerging Threats in Internet of Things Voice Services. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2019, 17, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Bagci, I.E.; Yan, J.; Roedig, U. Smart Speaker privacy control—Acoustic tagging for Personal Voice Assistants. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J.; Zimmerman, B.; Schaub, F. Alexa, Are You Listening? Privacy Perceptions, Concerns and Privacy-seeking Behav-iors with Smart Speakers. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 2018; Available online: https://www.key4biz.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/cscw102-lau-1.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Turner, H.; Lovisotto, G.; Martinovic, I. Attacking Speaker Recognition Systems with Phoneme Morphing. In Proceedings of the ESORICS 2019: Computer Security, Luxembourg, 23–27 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mitev, R.; Miettinen, M.; Sadeghi, A.R. Alexa Lied to Me: Skill-based Man-in-the-Middle Attacks on Virtual Assistants. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Asia CCS ’19, Auckland, New Zeland, 9–12 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castell-Uroz, I.; Marrugat-Plaza, X.; Solé-Pareta, J.; Barlet-Ros, P. A first look into Alexa’s interaction security. In Proceedings of the CoNEXT ’19 Proceedings, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–12 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, Y.; Sethi, S.; Jadoun, A. Alexa’s Voice Recording Behavior: A Survey of User Understanding and Awareness. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, ARES ’19, Canterbury, UK, 26–29 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Furey, E.; Blue, J. Can I Trust Her? Intelligent Personal Assistants and GDPR. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), Istanbul, Turkey, 18–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.; Fawaz, K.; Shin, K.G. Continuous Authentication for Voice Assistants. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, MobiCom ’17, Snowbird, UT, USA, 16–20 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Yan, C.; Ji, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, T.; Xu, W. DolphinAttack: Inaudible Voice Commands. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications, CCS ’17, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, İ.; Bostancı, E.; Güzel, M.S. Forensic Analysis with Anti-Forensic Case Studies on Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant Build-In Smart Home Speakers. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Samsun, Turkey, 10–15 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ni Loideain, N.; Adams, R. From Alexa to Siri and the GDPR: The gendering of Virtual Personal Assistants and the role of Data Protection Impact Assessments. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2020, 36, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Sun, W. I Can Hear Your Alexa: Voice Command Fin-gerprinting on Smart Home Speakers. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Washington, DC, USA, 10–12 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sangal, S.; Bathla, R. Implementation of Restrictions in Smart Home Devices for Safety of Children. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Networks (ISCON), Mathura, India, 21–22 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds, E.; Hubbard, S.; Lau, T.; Saraf, A.; Cakmak, M.; Roesner, F. Toys that Listen: A Study of Parents, Children, and Internet-Connected Toys. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’17, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, H.; Tang, C. Using Granule to Search Privacy Preserving Voice in Home IoT Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 31957–31969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shi, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Saxena, N. WearID: Wearable-Assisted Low-Effort Authentication to Voice Assistants using Cross-Domain Speech Similarity. In Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, ACSAC ’20, Austin, TX, USA, 7–11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub, G.; Flechais, I. “Alexa, Are You Spying on Me?”: Exploring the Effect of User Experience on the Security and Privacy of Smart Speaker Users. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 305–325. [Google Scholar]

| Research Question | Discussion |

|---|---|

| RQ1: What are the emerging security and privacy concerns surrounding the use of VAs? | Virtual assistants have become more and more commonplace; as a consequence, the amount of data associated with their use and stored by the VA companies will have commensurately increased [2]. A review of current research will help to understand exactly how private and secure these data are from a user’s perspective. As well as this, we will better understand what risks there are and how they can, if possible, be mitigated. |

| RQ2: To what degree do users’ concerns surrounding the privacy and security aspects of VAs affect their choice of VA and their behaviour around the device? | As consumers adopt more technology, do they become more aware of the security and privacy aspects around the storage of these data? In the current climate, ‘big data’ is frequently in the news, and not always in a positive light [3,4]. Do privacy and security worries affect users’ decisions to select a particular device more than the factor of price, for instance, and do these worries alter their behaviour when using the device? Reviewing current research will give us empirical data to answer this question. |

| RQ3: What are the security and privacy concerns affecting first-party and third-party application development for VA software? | A review of research into how the development of VA software and its extensions is changing will highlight the privacy and security concerns with regard to these extensions, and how developers and manufacturers are ensuring that they are addressed. Additional insights might come from those in the research community proposing novel ideas. |

| Criteria for Inclusion | Criteria for Exclusion |

|---|---|

| INC1: The paper must present an empirical study of either security or privacy aspects of digital assistants. | EX1: Studies focusing on topics other than security or privacy aspects of digital assistants, such as broader ethical concerns or usage studies. These studies might have a passing interest in security or privacy, but not focus on these as the main investigation. |

| INC2: The outcome of the study must contain information relating to tangible privacy or security elements. | EX2: Grey literature—blogs, government documents, comment articles. |

| INC3: The paper must be full research, peer reviewed, and published in a journal or conference proceedings. | EX3: Papers not written in English. |

| Research Paper | Key Findings | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Burbach et al. [11] | This paper studied user acceptance of particular VAs, and the factors influencing the decision to adopt one over the other. The relative importance of language performance, price, and privacy were observed among a control group of participants. The authors devised a choice-based conjoint analysis to examine how each of these attributes might affect the acceptance or rejection of a VA. The analysis took the form of a survey divided into three parts—user-related factors (age, gender), participants’ previous experience with VAs (in the form of a Likert scale), and self-efficacy (the users’ ability to operate the technology). The results found a fairly representative female–male split (53% to 47%) in terms of who tended towards an affinity with technology. Of particular interest was one question asked of the participants—“how would you react if someone were to install a VA without asking”—at which most of the participants protested. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Behaviour |

| Zhang et al. [14] | A case study of voice masquerading and voice squatting attacks using malicious skills; in this paper, the authors were able to successfully circumvent security vetting mechanisms used by Amazon and Google for checking submissions of apps written by third-party extension developers. The paper demonstrated that malicious applications can pass vetting, and the authors suggested novel techniques for mitigating this loophole. The authors have subsequently approached both Amazon and Google with their findings and have offered advice on how such voice squatting attacks via malicious skills might be prevented from entering their app stores. | 1. Developer 2. Security 3. Apps |

| Castell-Uroz et al. [20] | This paper identified and exploited a potential flaw in Amazon’s Alexa which allows the remote execution of voice commands. The authors first analysed network traffic to and from an Echo Dot smart speaker using man-in-the-middle techniques in Burp Suite; however, the privacy of the communications was deemed to be sufficiently robust. The flaw was uncovered using an audio database of some 1700 Spanish words played near the device. Using those words which were able to confuse the device into waking, in combination with a voice command as part of a reminder, the device was found to ‘listen’ to itself and not discard the command. The attack, although not developed further, was deemed by the authors to be sufficient for a malicious user to make online purchases with another user’s VA. | 1. End-User/Developer 2. Security 3. Exploit |

| Mitev et al. [19] | This paper demonstrated a man-in-the-middle attack on Alexa using a combination of existing skills and new, malicious skills (third-party extensions). It showed more powerful attacks than those previously thought possible. The authors found that skill functionality can be abused in combination with known inaudible (ultrasound) attack techniques to circumvent Alexa’s skill interaction model and allow a malicious attacker to “arbitrarily control and manipulate interactions between the user and other benign skills.” The final result was able to hijack a conversation between a user and VA and was very hard to detect by the user. The new-found power of the attack stemmed from the fact that it worked in the context of active user interaction, i.e., while the user is talking to the device, thus maintaining the conversation from the user’s perspective. Instead of launching simple pre-prepared commands, the attack was able to actively manipulate the user. | 1. Developer 2. Security 3. Exploit |

| Lau et al. [17] | A study demonstrating end-user VA behaviour, along with users’ privacy perceptions and concerns. The paper presented a qualitative analysis based on a diary study and structured interviews. The diary study took the form of semi-structured interviews with 17 users and, for balance, 17 non-users of VAs. Users were asked to diarise instances of using the device and of accidental wake-word triggerings at least once per day for a week. This was followed up by an interview in the homes of the users, taking into account details such as where the device was placed and why. Non-users were interviewed separately and asked questions pertaining to their choice to not use a VA and privacy implications that might have had a bearing in the choice. Qualitative analysis of the interviews used a derived codebook to analyse and identify running themes and emergent categories. Results identified who was setting up the speaker (the user or another person), speaker usage patterns, and placement of the speaker according to perceived privacy of certain house rooms. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Behaviour |

| Javed et al. [21] | A study based on the hypotheses that Alexa is recording conversations without being woken, users are not aware of this, and it is a concern of users. In this paper, a study was made of Alexa’s recording, a survey of users was undertaken, and quantitative analysis performed. Participants in the survey were first screened to ensure they owned an Alexa-enabled device; records were made of the participants’ demographics. The main part of the survey asked participants about the VA’s data storage, access, and deletion behaviour; questions asked of the participants were also designed to demonstrate their awareness and perceptions of the VA’s unintended voice recording. Finally, the participants were asked questions according to Westin’s privacy classification to determine their level of concern about privacy, which were then used to make a quantitative analysis. Further results were obtained by forming three hypotheses about users’ perceptions in certain areas to see how many participants have correct or incorrect ideas about how Alexa works. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy/Security 3. Snooping |

| Turner et al. [18] | This paper presented a demonstration of a security attack, ‘phoneme morphing’, in which a VA is tricked into thinking a modified recording of an attacker’s voice is the device’s registered user, thus fooling authentication. It demonstrated the attack and quantitively analysed the variance in several attack parameters. The attack was predicated on a method which mapped phenomes (of which there are 44 in the English language) uttered by a known speaker, into phenomes resembling those spoken by the victim. Three stages of the attack were determined: offline, the phenome clustering of the source voice was performed; a recording of the victim’s voice was obtained to map phenomes between the source and target; finally, the transformed audio was played to the system. The attack’s success was measured using four key phrases, with significant variance in success—the lowest being 42.1% successful, and the highest being 89.5% effective. | 1. End-User 2. Security 3. Exploit |

| Furey et al. [22] | The paper examined the relationship between trust, privacy, and device functionality and the extent to which personally identifiable information (PII) was retrievable by an unauthorized individual via voice interaction with the device. The authors made a qualitative analysis of privacy breaches, and the extent to which General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has helped to address these. Using a script of voice queries to be asked of the target device (an Amazon Echo Dot), an unauthorized user was granted a five-minute session with the speaker to determine which of the script’s questions could extract PII from the device. The device itself was linked to several other accessories—a smartphone and a fitness watch—and the questions asked corresponded with GDPR’s definition of what may constitute PII. Results of PII were tabulated, as a demonstration of such information (sleep location, contacts, schedule) could be obtained. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Exploit |

| Feng et al. [23] | The study proposed and demonstrated a continuous authentication model through the use of wearables. Quantitative analysis of the demonstration’s results, when compared with existing methods, was presented. The authors’ proposed solution, ‘VAuth’, continuously samples the user’s speech to ensure that commands originate from the user’s throat. VAuth, shown as a prototype device attached to a pair of spectacles, connects to the VA via Bluetooth and performs the speech comparison using an extension app, or skill. By using a skill, the comparison code can make use of server-side computing power. Built using Google Now in an Android host, VAuth was tested on 18 participants who each uttered 30 separate voice commands. The system detected the users with an overall 97% accuracy rate. | 1. End-User/Developer 2. Security 3. Authentication |

| Zhang et al. [24] | The paper demonstrated the ‘dolphin attack’, in which inaudible (freq. > 20 KHz) voice commands can be used to communicate with VAs, evading detection by human hearing. The paper presented a quantitative analysis of various attack parameters, and performed a successful demonstration on a number of Vas, including Siri, Google Now, Samsung S Voice, Cortana, and Alexa. Results of the experiment were ultimately tabulated, showing the device used, whether the command was recognized by the device, and then whether the command resulted in device activation. The maximum distances from the VA device’s microphone were also recorded—an important point of note, as the maximum distance was 1650 mm, indicating that the attack, although successful, does rely on being proximate to the device in question. | 1. End-User 2. Security 3. Exploit |

| Kumar et al. [15] | This paper was a demonstration of ‘skill squatting’ attacks on Alexa, in which a malicious skill is used to exploit the VA’s misinterpretation of speech to perform complex phishing attacks. Kumar et al. presented a successful demonstration and quantitative analysis and classification of misinterpretation rates and parameters, and highlighted the potential for exploitation. The attack was predicated on the use of speech misinterpretations to redirect a user towards a malicious skill without their knowledge. The authors first used a speech corpus to provide structured speech data from a range of American subjects. Finding that Alexa only managed to correctly interpret 68.9% of the words in the corpus, the authors were able to classify interpretation errors (homophone, phonetic confusion). They were then able to identify existing genuine skills with easily confusable names (“cat facts” becomes “cat fax”) and use predictable errors to redirect users to a malicious skill of their construction. As a counterpoint, the authors offered some measures which Amazon et al. might take to prevent such malicious skills from entering the app store, including phoneme-based analysis of a new skill’s name during the store’s certification process. | 1. End-User/Developer 2. Security 3. Exploit |

| Yıldırım et al. [25] | This study presented an overview of Amazon and Google VAs as a source of digital forensic evidence. A brief study was undertaken with qualitative analysis. The study was predicated on searching a VA device (a Samsung smartphone) for activity history entries relating to voice commands that had been issued. Data including the voice command in text form, timestamps, and the assistant’s response were found. No study was made of the cloud service platforms used to power the VAs in question; only the local device was examined. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Forensics |

| Loideain et al. [26] | Loideain et al. presented a qualitative study on the gendering of VAs, and the consequential societal harm which might result. VAs are generally gendered decisively as female and the authors argued that this gendering may enforce normative assumptions that women are submissive and secondary to men. The paper examines how GDPR and other data protection regulations could be used to address the issue; in particular, the study branched out into asking questions about the further role that data regulation might take in in AI design choices in areas such as equality and consumer law. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Behaviour |

| Kennedy et al. [27] | This paper studied a fingerprinting attack in which an eavesdropper with access to encrypted VA network traffic can use the data to correctly infer voice commands using machine-learning-derived fingerprints. An in-depth quantitative analysis of the attack metrics and success rate was introduced. The programming language Python was used to process traffic obtained from the network using the tool Wireshark; over 1000 network traces were obtained. The author’s software, ‘eavesdroppercollecting’, inferred voice commands from encrypted traffic with 33.8% accuracy. The authors went on to address the limitation in similar attacks which adopt this accuracy as their only metric; they proposed ‘semantic distancing’ as a further metric, whereby an attacker might infer a voice command that was different from, yet similar to, the original command. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Exploit |

| Sangal et al. [28] | A study of safety issues surrounding the use of VAs by children. The paper offered a qualitative analysis of the problem and a proposal for a solution, with an analysis of the success rate thereof. The proposed solution aimed to address the problem that a VA, in normal circumstances and with no authentication enabled, can be used by anyone in its vicinity, whether child or adult. Several AI algorithms were posited, based on such metrics as voice frequency (assumed to be higher in a child), intended to form part of an improved service by the VA provider. Google and Amazon were used in the study. | 1. End-User 2. Security/Privacy 3. Authentication |

| Cheng et al. [16] | The paper proposed a novel method of ‘watermarking’ user interaction with a VA (Google Home). The authors presented a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the problem and the success of the proposed solution. The proposed solution took the form of an acoustic ‘tag’—a small, wearable device that emits an audible signal unique to that tag which can act as a form of authentication that is far more sophisticated than a standard VA wake word. In this instance, the authentication is not continuous—that is, it is only used at the start of a transaction, similar to any PIN or password. The authors experimented with tags that emitted audible, unnoticeable, or hidden signals. An analysis of the chosen design implementation (an audible tag) was carried out using a Google Home smart speaker, of which the audio capabilities (recording fidelity and sampling rates) were known beforehand. | 1. End-User 2. Security 3. Authentication |

| McReynolds et al. [29] | The paper presented a study of privacy perceptions surrounding ‘connected toys’. It introduced a quantitative analysis of data gathered through interviews and observation. Two connected toys were used, ‘Hello Barbie’ and ‘CogniToys Dino’. Semi-structured interviews with parent-child pairs were conducted, covering three research questions—general interaction, privacy, and parental controls. Child participants were aged between six and 10 years. While watching the child play with the toys, the parents were asked the first set of questions. The second and third sets of questions were asked after the parent and child had been separated. The interviews were transcribed, and a codebook was developed to categorise the responses to the interview questions. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Behaviour |

| Wei Li et al. [30] | The authors proposed a novel way of ‘encrypting’ user voice commands using the granule computing technique. The paper detailed a quantitative analysis of the problem and the proposal’s success. Unlike existing VA client endpoints—of which the computing is used primarily to listen for a wake word and to sample subsequent audio information for transportation to the cloud for processing—the author’s model performed most of the computing on the VA device. Each sound could be encrypted using the advanced encryption standard (AES), using a different key for each voice, decreasing the likelihood that a malicious attacker could decrypt the content. | 1. End-User 2. Privacy 3. Authentication |

| Wang et al. [31] | Wang et al. proposed ‘WearID’, whereby a smartwatch or other wearable is used as a secure token as a form of two-factor authentication to a VA. The paper presented a quantitative analysis of the proposal’s success rate and an in-depth analysis of the problem. WearID uses motion sensors—accelerometers—to detect the airborne vibrations from the user’s speech and compares it to known values using cross-domain analysis (sampled audio vs. vibration) to authenticate the user. The authors proposed that the technology could be used “under high-security-level scenarios (e.g., nuclear power stations, stock exchanges, and data centers), where all voice commands are critical and desire around-the-clock authentication.” WearID was shown, using two prototype devices (smartwatches) and 1000 voice commands, to correctly authenticate users with 99.8% accuracy, and detect 97.2% of malicious voice commands, both audible and inaudible. | 1. End-User 2. Security 3. Authentication |

| Chalhoub and Flechais [32] | The paper presented a study on the effect of user experience on security and privacy considerations of smart speakers. It introduced qualitative and quantitative analysis of data gathered through theoretical reasoning and interviews. The authors discovered factors influencing smart speaker adoption and security/privacy perception and trade-offs between the two. Interviews were coded with grounded theory for analysis; 13 participants were involved in the study. The themes of the interview included perceptions and beliefs towards privacy resignation, the usability of security controls, trigger points for security and privacy considerations, factors for adoption, and privacy/security tradeoffs with User Experience (UX) personalization. The study found that users reported ‘compensatory behaviour’ towards non-user-friendly security and privacy features. | 1. End-User 2. Security and Privacy 3. Behaviour |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bolton, T.; Dargahi, T.; Belguith, S.; Al-Rakhami, M.S.; Sodhro, A.H. On the Security and Privacy Challenges of Virtual Assistants. Sensors 2021, 21, 2312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072312

Bolton T, Dargahi T, Belguith S, Al-Rakhami MS, Sodhro AH. On the Security and Privacy Challenges of Virtual Assistants. Sensors. 2021; 21(7):2312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072312

Chicago/Turabian StyleBolton, Tom, Tooska Dargahi, Sana Belguith, Mabrook S. Al-Rakhami, and Ali Hassan Sodhro. 2021. "On the Security and Privacy Challenges of Virtual Assistants" Sensors 21, no. 7: 2312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072312

APA StyleBolton, T., Dargahi, T., Belguith, S., Al-Rakhami, M. S., & Sodhro, A. H. (2021). On the Security and Privacy Challenges of Virtual Assistants. Sensors, 21(7), 2312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072312