3.2. Viscosity

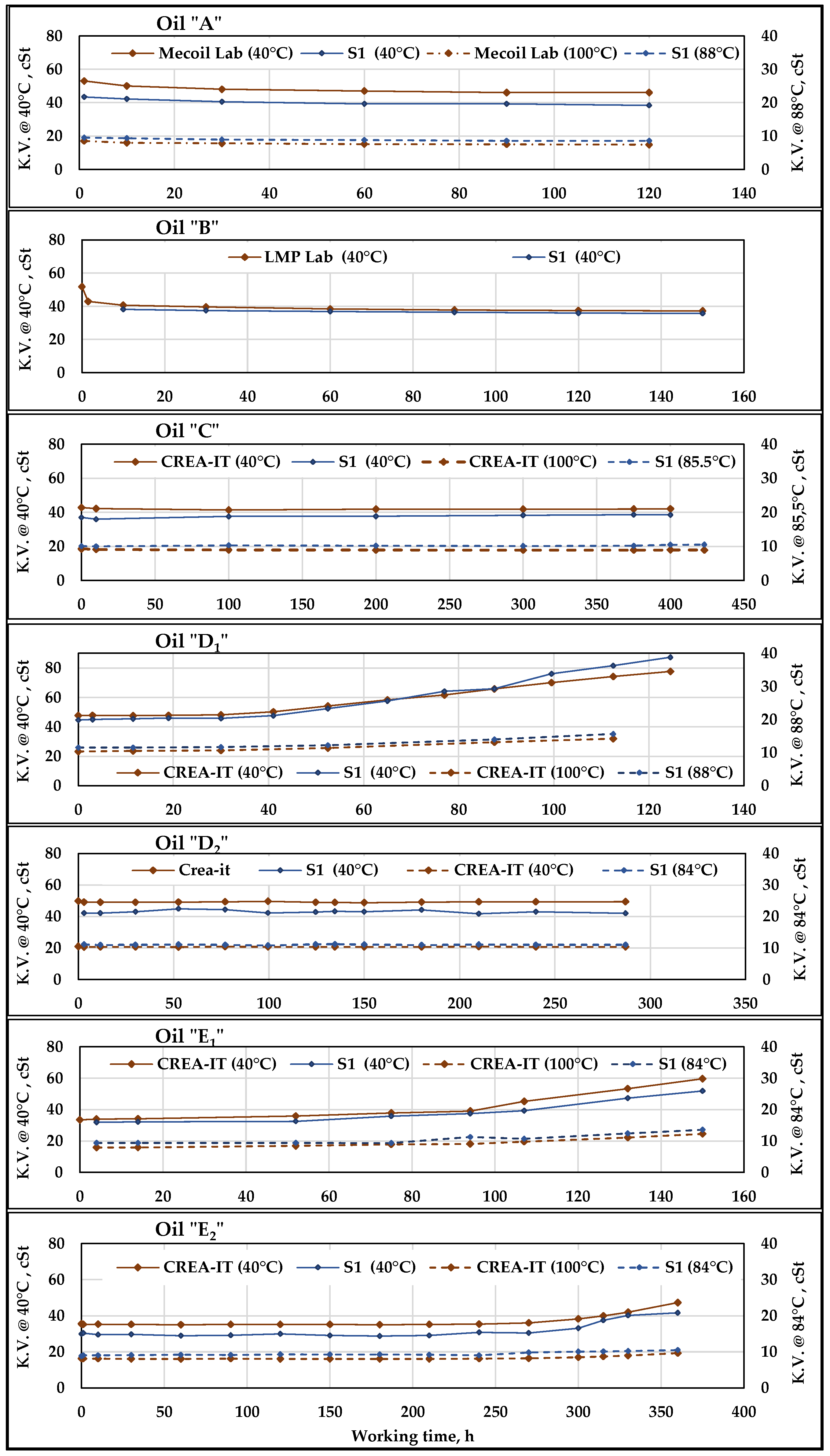

The results of the viscosity measurements, both by the sensor

S1, and the laboratory involved time by time, are shown in

Figure 8 for the seven oils described in

Section 2.5. Each viscosity value should be accompanied by the relating uncertainty value reported in the

Table 9 and

Table 10, respectively for laboratories and sensor. Despite their higher extended uncertainty, which ranges from 6.18% to 9.54%, the sensor

S1 seemed to be capable of correctly monitoring the trend of the viscosity.

Figure 8.

Kinematic Viscosity (K.V.) measurements provided by S1 compared to the Lab-data at 40 and 100 °C. The diagrams refer to the seven oils subjected to working cycles of different duration. S11 measurements were made with oil at 40 °C while S12 provides the highest temperature values observed at the 40 MPa overpressure valve outlet (indicated in the legenda).

Figure 8.

Kinematic Viscosity (K.V.) measurements provided by S1 compared to the Lab-data at 40 and 100 °C. The diagrams refer to the seven oils subjected to working cycles of different duration. S11 measurements were made with oil at 40 °C while S12 provides the highest temperature values observed at the 40 MPa overpressure valve outlet (indicated in the legenda).

The lab viscosity was measured at 40 and 100 °C.

S11 measurements at 40 °C were possible by suitably adjusting the flowrate in the related section (

Figure 6b) in order to allow the oil to cool to the lower ambient temperature, passing from about 60 °C, typical for the delivery line of the test rig, to the new thermal equilibrium point of 40 °C, with very small oscillations. As to the oil at high temperature, despite the thermocouple, installed at the very outlet of the 40 MPa overpressure valve, normally indicate temperature levels of 99–100 °C, the viscosity measurements were made by

S12 about 40 cm downstream and suffered the same oil cooling phenomenon just described for

S11. Thus, the average temperature of the oil entering varies from 84 to 88 °C, depending on the ambient temperature. The

S12 viscosity values and the Lab-data at 100 °C were, however, compared to evaluate the behaviour of the sensor under high temperature conditions.

The diagrams of

Figure 8 show that in Oil

B test,

S12 measurements were not carried out, due to a sensor failure, while

S11 measurements at 40 °C started at 10 h working time. In the Oil

D2,

S11 data collection started after 90 h from test start, due to problems in the data acquisition system.

Despite some differences in the viscosity values, those provided by both

S11 and

S12 have trends similar to those of the Lab-data. It can be observed that the related curves are parallel, describing the evolution of the parameter during each test depending on the characteristics of the related oil. It can be noticed that for the oils

A and

B (UTTOs) there is an initial, rapid drop in viscosity (caused by intense transmission shear stress) which then remains quite stable, while the viscosity of

C (hydraulic bio-based synthetic ester) keeps constant in a far longer test.

D1 and

E1 were refined vegetable oils added with antioxidant [

4]. They underwent a progressive oxidation process from 40 to 50 h of work until the end of the test, which caused a progressive increase in viscosity, both at 40 °C and at high temperature. According to the diagram’s trends, such variations were contemporaneously detected by Lab data and sensors, which provided very similar trends of the curves of Lab-data and of

S11 and

S12, in both thermal conditions. Considering that in real working conditions the frequency of oil sampling for analysis is rather lower than in our test and that the laboratory needs time to provide its results, the sensor

S1 proved to be effective in detecting the variations in viscosity.

Increasing the concentration of antioxidant to the same vegetable oil bases provided the oils

D2 and

E2 whose performance was significantly improved, as their viscosity remained substantially stable up to about 275 h, when the increase started, although following a less marked trend than in

D1 and

E1. Moreover, in this case, the curves provided by laboratory and sensors had very similar, parallel trends. As mentioned above, the parallelism of the curves of Lab-data (taken as a reference) and of the sensors depends on the differences between the values obtained, point by point, in the two modes: since the chemical–physical characteristics of the oils vary type-by-type, they can differently affect the measurements carried out of by the sensors according to the factory pre-set calibration. Apart from this, what seems to be more important is the capability of

S1 sensors to monitor the viscosity variations, considering that one of the basic criteria to assess oil oxidation stability indicates a 20% increase in the viscosity at 40 °C as the limit for oil replacement (ISO 4263-3: 2015) [

36]. In

Table 11, the variations in viscosity observed at the end of each oil test are reported, both absolute and in percentage. The

S1 percent variations are sometimes higher and sometimes lower than those of the laboratory, but they are always of the same order of magnitude. The presence of such sensors in a plant would be therefore useful to continuous monitoring, to promptly detect any variations in viscosity measurement. The use of sample analysis would be greatly reduced and limited to punctual analyses to dispel any doubts about the correctness of the variations detected by the sensors.

The series of measurements provided by

S1 and by the laboratory underwent the test of Pearson. The resulting coefficients of correlation “

r” and the probability “

p” of uncorrelation are also reported in

Table 11.

The results of the test of Pearson confirmed the above considerations, with high correlation between lab and sensor series of values during of all oils tests except for “

C”. In this case, the low or negative correlation of data is explained by the very small viscosity variation, which testify that the viscosity remined substantially stable during more than 400 h in both lab and sensor series, as can be observed in

Figure 8 (oil “

C”).

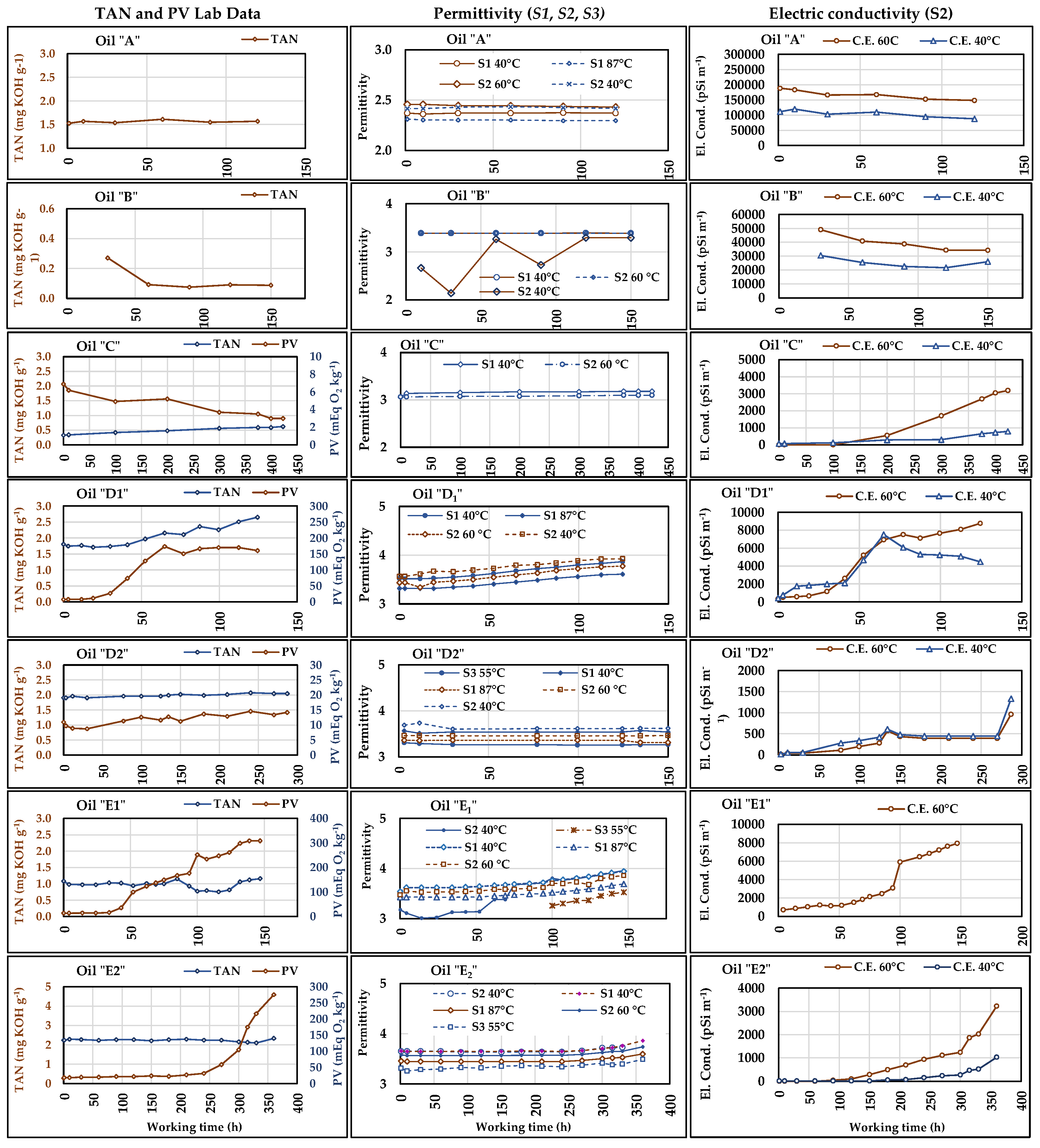

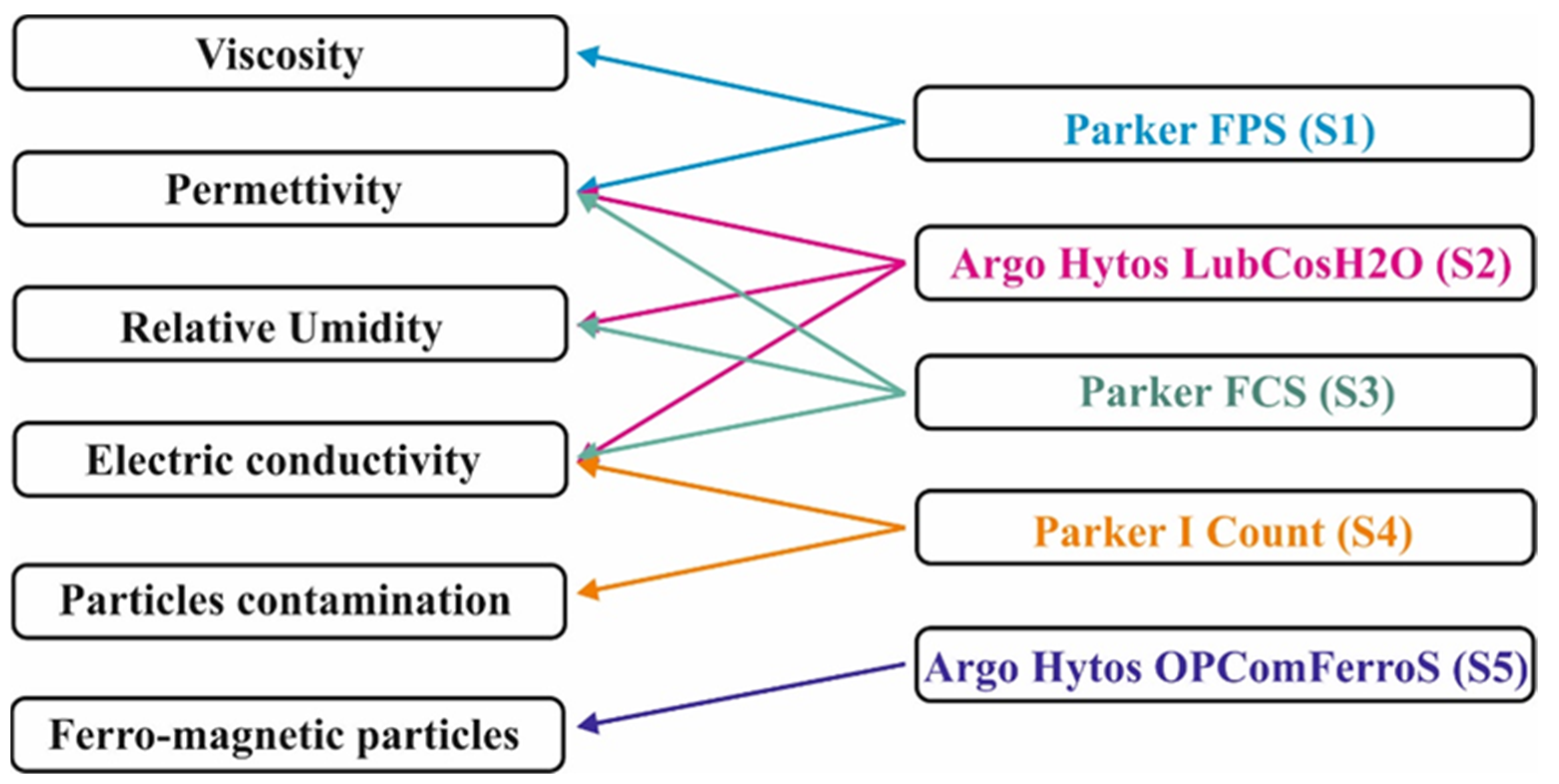

3.3. Permittivity

The permittivity was measured by the sensors

S11 (T = 40 °C),

S12 (T = 88 °C),

S2 (T = 60 °C), and

S4 (T = 55 °C). The trends of the permittivity provided by the sensors were compared to the lab analyses results of

PV and

TAN to assess the capability of permittivity to detect the presence of any primary or secondary oxidation processes. The average extended uncertainty in permittivity measurements (

Table 10) resulted lower than in lab determination of

TAN and

PV (

Table 9). The trends of the measurements are shown in

Figure 9. The diagrams of

PV and

TAN are reported in the left column, while those of the permittivity are in the central column. The missing Lab-data indicate the tests in which the relative analyses were not carried out, such as for

PV in oils

A and

B. The lack of the data of a particular sensor means that it had not yet been installed or that some problem occurred in the acquisitions system.

The diagrams in

Figure 9 show that the

TAN never had relevant variations but, in the oil,

D1, from an initial value of about 1.8 mg KOH g

−1, it started to increase after 40 h and rose up to 2.7 mg KOH g

−1. “

D1” was one of the vegetable oils with lower concentration of antioxidant, and the same diagram shows that the increase in

TAN was preceded by an increase in

PV (started at about 20 h), which means that both primary and secondary oxidation processes were occurring in

D1.

Despite the differences among the values the sensors provided, their permittivity curves are substantially parallel, and their trends start to increase contemporaneously to the PV/TAN trends, similar to what was observed for the viscosity (see

Section 3.2). With reference to the beginning of the test, the permittivity measured at the end of test increased by 11.56% and 11.58%, respectively for

S11 (40 °C) and

S2 (60 °C), while for

S12 (88 °C) the variation resulted in being slightly lower (10.28%). On the contrary, for the permittivity calculated at 40 °C by

S2, the variation was slightly higher (12.1%). Therefore, there is concordance between the laboratory results and sensors. According to the recommendations reported in

Section 2.1 about the permittivity, a hypothetic detecting the above variations in a working plant should induce the checking of the oil’s condition, and probably to replace it.

The considerations made for the permittivity in

D1 can be extended to the tests with “

E1” and “

E2”, i.e., the tests with the same vegetable oil that respectively lasted 150 h and 360 h due to the presence in “

E2” of a higher antioxidant concentration. In

Figure 9, relevant permittivity variations can be observed in these tests. In these cases, the increase in permittivity accompanied the increase in

PV, as the

TAN, apart from some oscillations, remained stable in both cases. In

E1 the

PV variation started around 40 h of work, as the permittivity started to increase at about 50 h, when the peroxide value became relevant (≅100 mEq O

2 kg

−1). In

E1, the curves of permittivity of

S11 (40 °C),

S2 (60 °C), and

S12 (88 °C) were parallel, and the variations referred to the test start value were respectively 0.32 mg KOH g

−1 (10.25%), 0.31 mg KOH g

−1 (10.16%), and 0.26 mg KOH g

−1 (8.78%). The curve of the permittivity calculated at 40 °C by

S2 appears very irregular probably due to some problem that occurred in the sensor. At 100 h of test, the sensor

S3 was installed and had begun to measure the permittivity (at 55 °C), showing an increasing trend someway similar to the previous ones. In

E2, the sensors detected the oil alteration at about 250 h of work, corresponding to the sampling time of the oil that showed an increase in

PV in lab analyses. In this case, all sensors had similar trends, with constant differences among the values provided point by point, which determined the parallelism of their curves that substantially follow the trend of the

PV in the relative diagram. The percent variations in permittivity were of about 5% for all sensors.

Figure 9.

Trends of the permittivity measured by S1, S2, and S4 and of the electric conductivity (EC) measured by S2, both compared to the Lab-data of TAN and PV. The diagrams refer to the seven oils subjected to working cycles of different duration. The two S1 worked with oil at 40 °C and at high temperature (about 87 °C) at the 40 MPa valve outlet; S2 and S4 data refer to the actual oil temperature in the delivery section (around 60 °C). S2 also provided the permittivity and E.C. values measured at the actual oil temperature in the delivery section (values indicated in the legenda) and the calculated values at 40 °C.

Figure 9.

Trends of the permittivity measured by S1, S2, and S4 and of the electric conductivity (EC) measured by S2, both compared to the Lab-data of TAN and PV. The diagrams refer to the seven oils subjected to working cycles of different duration. The two S1 worked with oil at 40 °C and at high temperature (about 87 °C) at the 40 MPa valve outlet; S2 and S4 data refer to the actual oil temperature in the delivery section (around 60 °C). S2 also provided the permittivity and E.C. values measured at the actual oil temperature in the delivery section (values indicated in the legenda) and the calculated values at 40 °C.

As previously said, the TAN variations were also very small in the longer tests. For instance, in “C” the TAN started from 0.33 mg KOH g−1 and following a constant trend, it reached 0.62 mg KOH g−1 after 423 h, with an absolute variation of 0.29 mg KOH g−1, while, for TAN variations, the attention level was 2 mg KOH g−1. In this test, the permittivity measured by S11 (40 °C) and S2 (60 °C) had similar behaviour. The increase was by 1.3% (0.04 in absolute value) in both cases, confirming the tendency of TAN, despite the decreasing of PV whose values, however, were probably always too low to affect the permittivity.

The results of the test of Pearson to assess the correlation between the series of permittivity values of each sensor and those of

TAN and

PV are reported in

Table 12. In the test with “

C”, we can see a high positive correlation between permittivity and

TAN and high negative correlation with

PV, which confirms the above comments to the diagrams of the same test

C about the low

PV level. High “

r” values and very low “

p” values can be observed in the tests on the oils

D1,

E1, and

E2, confirming that the sensors are suitable for monitoring the oil status relating to the risk of occurrence of any oxidation processes.

The test of Pearson was also carried out on the series of data provided by the sensors and indicated high correlation among the sensors in the same cases in which they were highly correlated to

TAN or

PV (tests on

C,

D1,

E1, and

E2”).

Table 13 shows these results, with always high “

r” values, while “

p” resulted higher (

p > 0.05) for

S3, which reflects some irregularities observed in

Figure 9.

Although any detected variation in permittivity requires laboratory analysis of the samples in order to establish the causes and exactly quantify the alteration in progress, the use of sensors can help to significantly reduce the number of analyses and at the same time allow continuous monitoring of plants and machines in operating conditions. Beyond the generally similar parallel trends provided by the three sensors,

S1 measurements appeared more regular and reliable, including at high temperature, while some irregularities occurred to

S2 (

S2 60 °C in

Figure 9), and less data were available for

S3.

S1 also showed the lowest uncertainty (

Table 9). Eventually, it is important to underline that the temperature influences the permittivity. If oil temperature during monitoring is not constant, it will not be possible to correctly evaluate any permittivity variations. From this point of view, the

S2 function which calculates the permittivity at 40 °C from the permittivity at oil actual temperature, would be very useful in oil monitoring. However, due to several anomalous trends observed in the curves for the

S2 40 °C tests on

B,

D2, and

E1, (

Figure 9), its reliability needs to be verified in further tests.

3.4. Electric Conductivity

The electric conductivity (

E.C.) was measured by

S2 at fluid operating temperature (60 °C).

E.C. measurements were compared to those of

TAN,

PV, and

RH, parameters which could actually affect the electric conductivity of liquids. As regards the determination of

Ū(x)%, the manufacturer of

S2, declared that in the interval, 2000 pSi m

−1 < E.C. < 800,000 pSi m

−1, the sensor accuracy was 15 pSi m

−1, i.e., ranging from 0.002% to 0.75%. For E.C. < 2000 pSi m

−1, the accuracy decreased to 200 pSi m

−1, which results in very high percent uncertainty. Therefore, in

Table 10,

Ū(x)% was reported only for E.C. > 2000 pSi m

−1 (in the test with the oil

D2,

E.C. always remained below 2000 pSi m

−1). As for the permittivity,

S2 also provided the calculated values of

E.C. referred to 40 °C. The series of

E.C. values measured in the seven oil tests are shown in

Figure 9 (right column diagrams). It can be noticed that in tests

A and

B, the

E.C. was much higher than in all other tests, probably due to specific characteristics and additives of the two UTTOs compared to those of hydraulic fluids and refined vegetable oils. On the contrary,

Ū(x)% resulted lower in tests

A and

B, with values respectively of 1.1% and 1.3%, compared to an average of 7.5% for the other oils. In general, similar to what was observed for the permittivity, the

E.C. trends seem to follow those of

TAN and

PV and to well describe the start and progression of oil status alteration, also when

E.C. < 2000 pSi m

−1, with very high uncertainty level. The curves of

E.C. calculated at 40 °C followed the expectably lower trends than those of

E.C. measured at 60 °C only in oils

A,

B,

C, and

E2, while the anomalous trends observed in the other oils confirm the low reliability of calculated data.

The test of Pearson was carried out to verify the presence of correlation between

E.C. (both measured, at 60 °C, and calculated, at 40 °C) and

TAN and

PV. Moreover, since

S2 also measures the oil relative humidity (

RH), the test of Pearson also regarded the possible correlation between

EC and

RH. The results are reported in

Table 14.

The results reported in

Table 14 are similar to those of permittivity, with the highest “

r” and lowest “

p” values in correspondence of the most relevant variations of

TAN and/or

PV, i.e., in the tests with oils

C,

D1,

E1, and

E2. As to the negative correlation between

EC and

PV, it is similar to that observed for permittivity in the same test and can be explained in the same way. In the test with the oil “

B”, the high “

r” values were accompanied by “

p” slightly higher than 0.05, which reduced the significance of the correlation. The

RH values provided by

S2 are shown in the diagrams of

Figure 11 (together with those of other sensors). The correlation between

RH and

EC is not evident in the seven tests carried out, probably because of the substantial stability of the humidity observed during all the work cycles against the variations of

EC, which was evidently caused by the increase in

TAN and

PV. The relationship between oil

RH values and the corresponding

EC measurements will be deepened in subsequent specific tests.

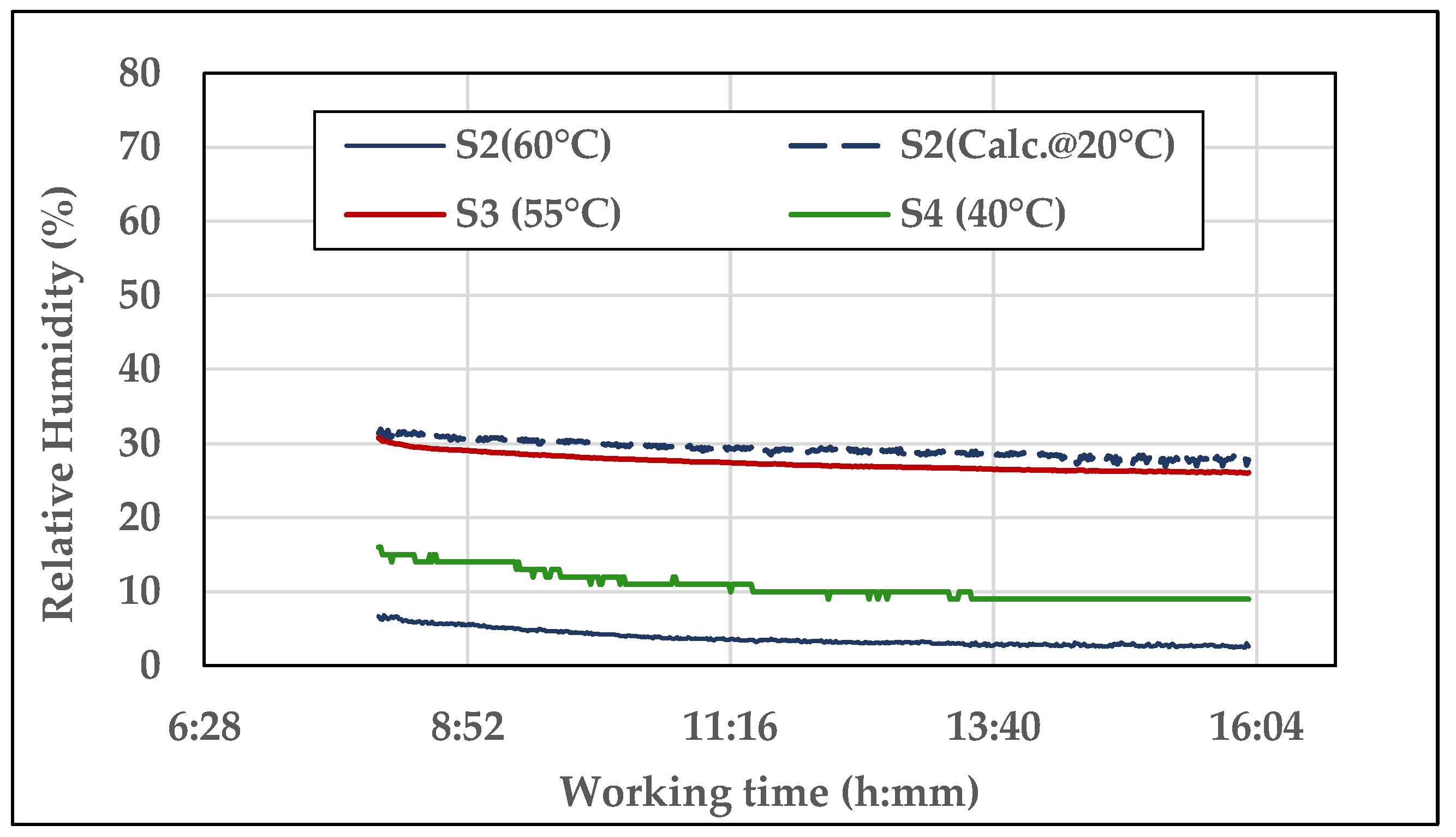

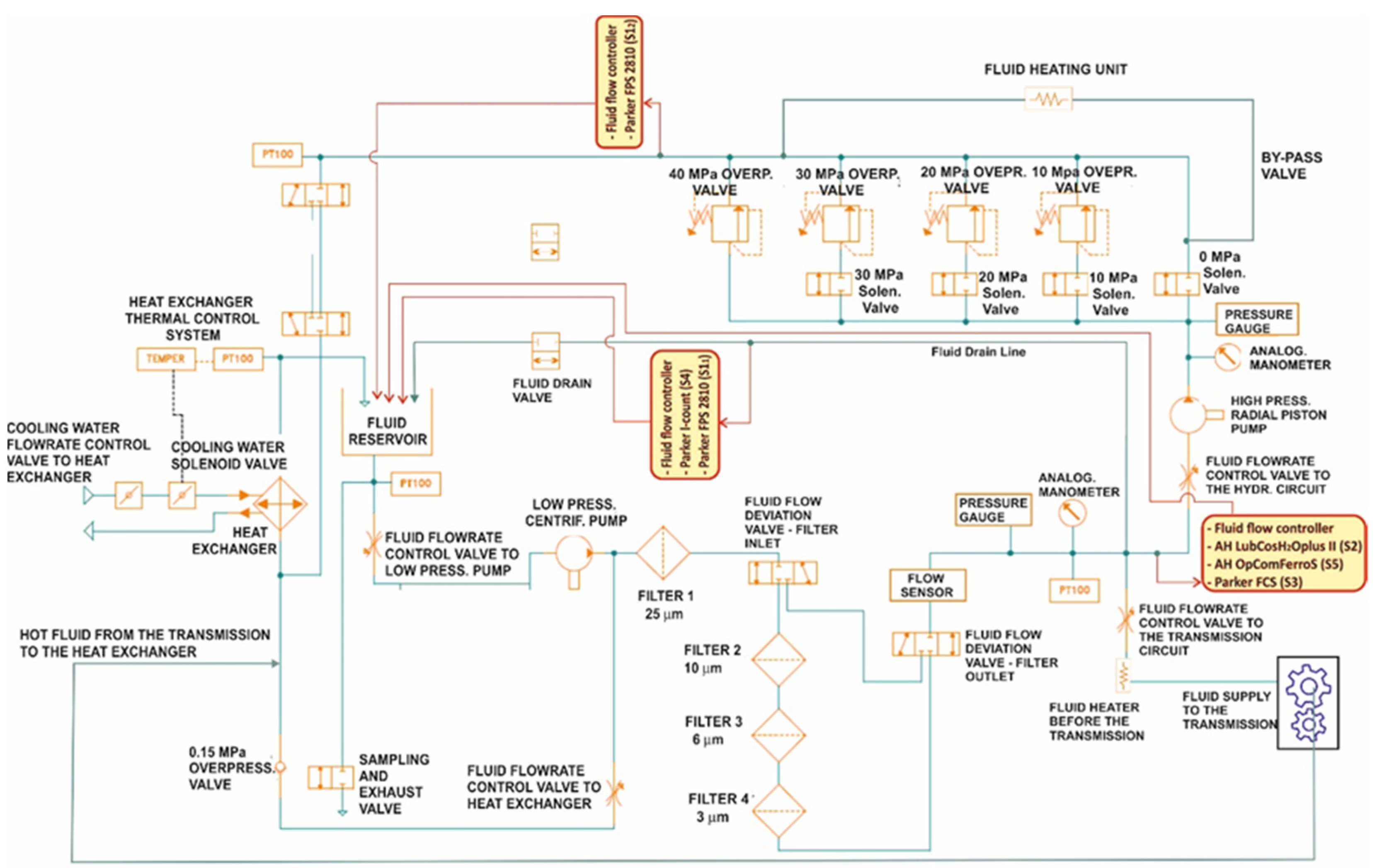

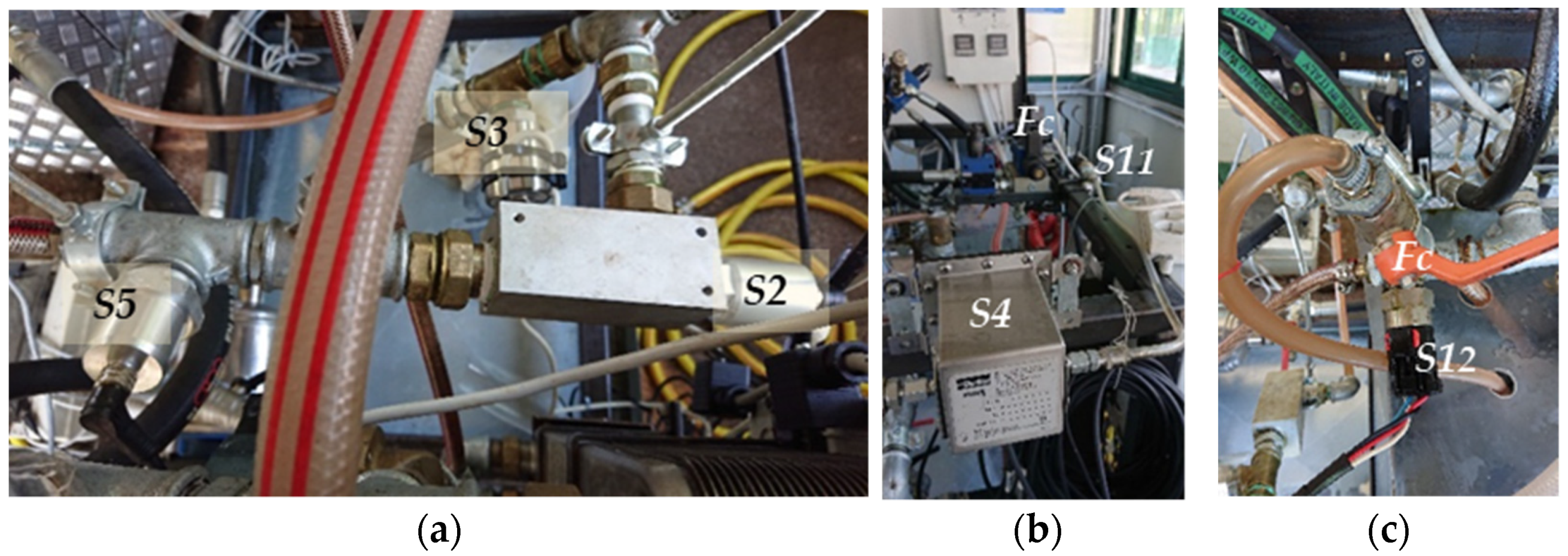

3.5. Water Content

The presence of water in the oils was measured as parts per million (ppm) in laboratory analysis and as relative humidity,

RH (%), by the sensors

S2,

S3, and

S4, at the temperature of the oil as it passes through each sensor, whose values were respectively 60 °C, 55 °C, and 40 °C. The differences depended on each sensor position and flowrate, differently set in order to achieve the most correct working conditions, which could favour the heat exchange between oil and external environment. As for the permittivity and the electric conductivity,

S2 also provided the

RH calculated at a reference temperature that in this case was 20 °C. Said differences in oil temperatures affect the measurement of

RH. The diagram in

Figure 10 shows the trends of

RH recorded by the sensors during one day of test.

Figure 10.

Example of the trends of the Relative Humidity measured by S2, S3, and S4 during one day of test (day 4, oil E2, time of test: about 9 h).

Figure 10.

Example of the trends of the Relative Humidity measured by S2, S3, and S4 during one day of test (day 4, oil E2, time of test: about 9 h).

The oil heating initial phase does not appear in the diagram and the data refer to constant oil temperature in each sensor. Although the different RH levels provided by the sensors, their curves follow similar trends, slightly decreasing during the day as the oil progressively loses part of the water it contains (which increased before the daily test starting due to the night drop in temperature), until the equilibrium point. The RH calculated at 20 °C by S2 is at the highest level (≅28%), while the RH at 60 °C, provided by the same sensor, is at the lowest (≅3%). The curve at 40 °C (by S4) is immediately over (RH ≅ 10%). The S3 curve at 55 °C (RH ≅ 26%) is anomalous because of its proximity to the S2 curve at 20 °C. It can be noticed that the trend of the curve S4 is less gradual than the others. From the observation of the recorded data, it resulted that the acquisition proceeds with a resolution of ±1.00 °C (resolution and accuracy were not reported in the data sheet o S4). As the calculation of the uncertainty in measurement refers to constant temperature, RH resulted in being constant as well, with s = 0. As a consequence, Ū(x)% could not be provided for S4.

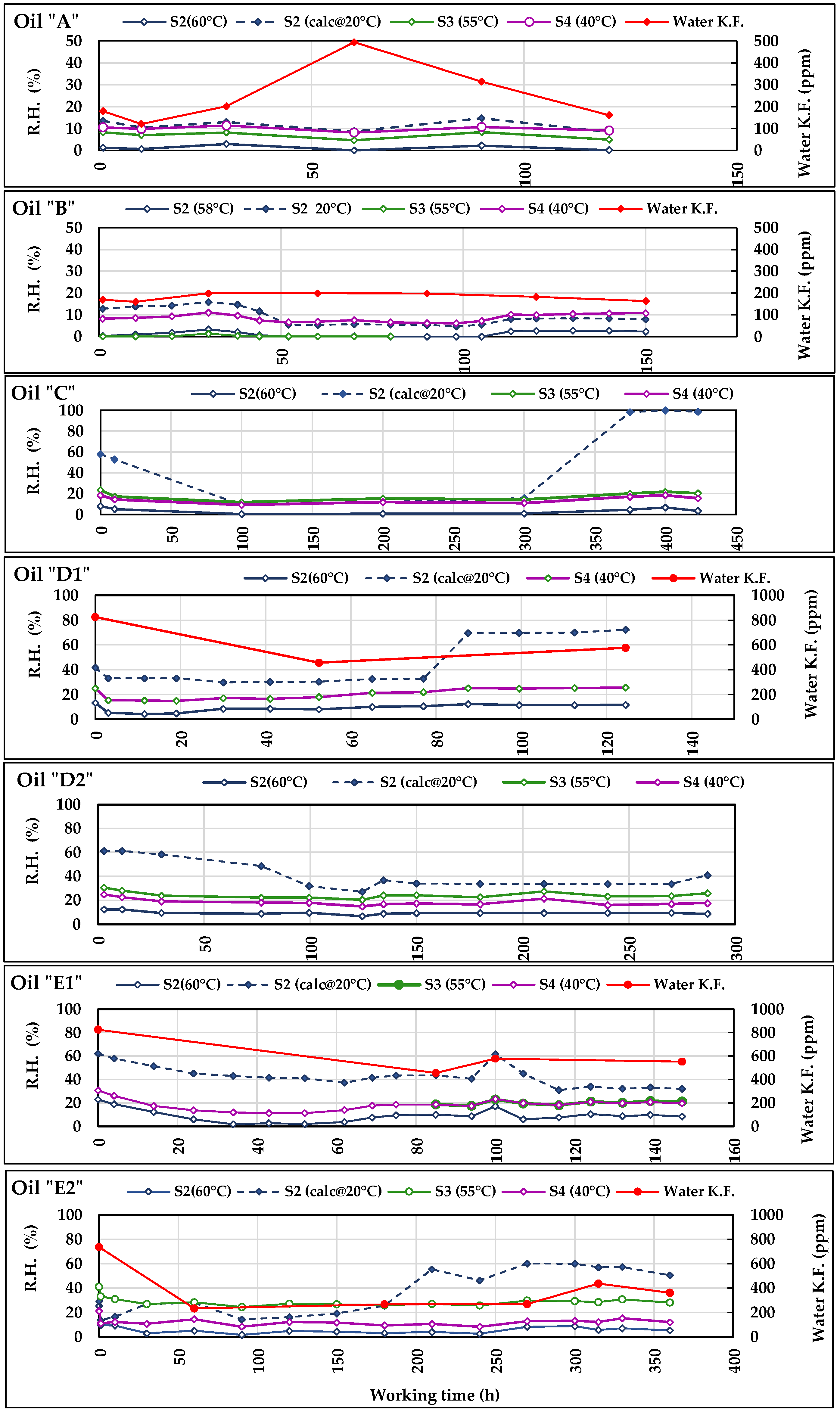

The laboratory analyses were carried out on the samples of oils

A,

B,

D1,

E1, and

E2 using the Karl Fisher method (ISO 8534:2017). They were compared to the average daily

RH values provided by the sensors recorded in the same days of oil sampling (

Figure 11). The uncertainty in lab and sensors measurements are reported, respectively, in

Table 9 and

Table 10. In particular,

Table 10 shows that, for

S2,

Ū(x)% greatly varies from oil to oil and this is probably due to the generally low humidity levels in the oils, often below the 10% limit that defines the interval (10–90%) of highest

S2 accuracy.

Ū(x)% appears more regular for

S3.

Figure 11.

Trends of the Relative Humidity measured by S2, S3, and S4 during the tests with the seven oils. In the diagram of oils A, B, D1, E1, and E2, RH trends are compared to those of the water content measured in laboratory according to Karl Fisher method.

Figure 11.

Trends of the Relative Humidity measured by S2, S3, and S4 during the tests with the seven oils. In the diagram of oils A, B, D1, E1, and E2, RH trends are compared to those of the water content measured in laboratory according to Karl Fisher method.

The comparison between absolute data as the water contents in ppm and relative data as

RH is difficult because of the above cited influence of temperature on the

RH level, the different units of measurement, and the risk of oil samples contamination by atmospheric water which could occur during the samplings or also in laboratory. However, the diagrams of

Figure 11 provide some general indications:

- −

The trends of

RH measured by the sensors

S2,

S3, and

S4 reflect what was observed in

Figure 10. Despite the different measured

RH levels, they follow parallel trajectories indicating the same variations, peaks, etc. This common behaviour of the sensors contributes to accrediting the general correctness of the measurements provided and above all their usefulness in highlighting any anomalous trends of the measured parameters.

- −

The trend of RH calculated at 40 °C by S2 is sometimes irregular (e.g., in C, D1, and E2 oils) and differs from the other curves of RH confirming the above doubts about the reliability of the calculated values of permittivity and electric conductivity provided by S2.

- −

The water contained in the oil is normally higher at the start of tests, and tends to decrease during the first period, then remaining substantially stable. Such a behaviour always occurred, except for B, both in Water-KF and RH.

- −

In the test with the oil A, the Water-KF trend shows an anomalous peak, which is in contrast with the trends of the curves of the sensors. Such a peak is probably an outlier and in the subsequent statistical elaboration the series was analysed both with and without its corresponding value.

- −

Most differences between the curves of Water-KF and those of RH are sometimes caused by the different number of available data: e.g., in B, D1, E1, and E2, the number of analyses is far lower than the daily RH values. In the case of E2, in which many more analyses have been carried out, a greater adherence of behaviour can be observed between the trends of water Water-KF and RH.

Furthermore, in this case, the statistical analysis was based on the test of Person and aimed at verifying any correlation at first between the data from lab analyses and sensors measurements, then, among the sensors. The results of this comparison are reported in

Table 15. In

C and the lab analyses were not carried out, as in

D2 the measurements by

S3 started at about 80 h of test. In

A and

B no correlation appeared. In

Table 15 appears the test

A1: here, the correlation analysis was made on the same dataset of the test

A from which the

Water-KF value at 60 h was eliminated as a probable outlier. The coefficients of correlation between sensors and Lab-data increased relating to “

A”, but the probability of uncorrelation remained high. Among the other tests, we find very high correlation coefficients in

D1 and

E1 for all sensors data (except for the

S2(calc@20 °C)) where, however, the probability of uncorrelation is higher than 0.05, probably due to the low number of data available for the test. Eventually, in

E2, in presence of more data than in previous tests, the correlation between

Water-KF data and those provided by

S2(60 °C),

S3(55 °C), and

S4(40 °C), was very strong, with high “

r” values corroborated by “

p” always lower than 0.05. Moreover, in this case, the

RH calculated at 20 °C was uncorrelated to the Lab-data.

The correlations between the data of sensors, considered pair by pair, are reported in

Table 16. Strong and very strong correlations are more frequent now, often confirmed by very low “

p” values, which reflect the parallel trends of the different

RH curves observed in

Figure 11. The cases of uncorrelation mostly occur in when the test regards the

RH calculated at 20 °C by

S2.

The above results indicate that the sensors seem capable of following the trend of the humidity in the oils and could be conveniently installed in plants where the risk exists of oil contamination by water, such as in presence of oil–water heat exchangers, taking care that monitoring is carried out at oil constant temperature. The variability among the levels of RH detected by the sensors was probably caused by the different characteristics of both sensors and oils and by their interactions. Despite this, all sensors answer to RH variations in the same way. Based on the relating uncertainty in measurements, S3 measurements appeared more reliable, while S4 was less precise and accurate. The calculation of RH at 20 °C provided by S2 was often irregular and does not seem reliable. As for the relationship between RH and the absolute water content, it could be clarified through specific tests that provide an adequate number of samples (and relative analysis results) and RH, taking care to avoid any contamination of the samples by environmental water.

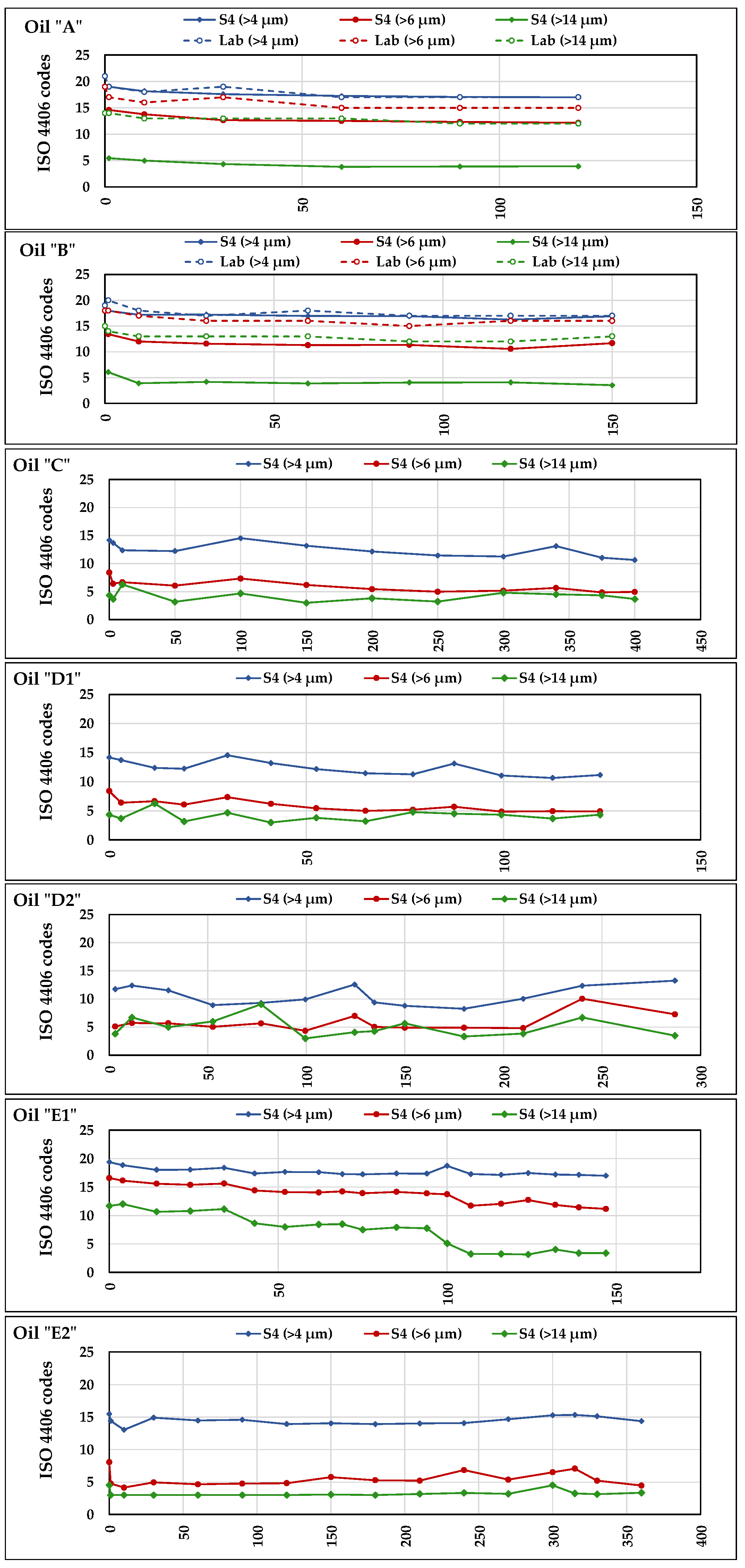

3.6. Particle Contamination

The level of particle contamination was determined in laboratory only for oils

A an

B at intervals of 30 h, while

S4 measurements were continuously carried out in all tests. Based on the number of particles detected in different dimensional classes, both methods provided the class of oil contamination according to the standards NAS 1638-2001 and ISO 4406:2021. Since no accuracy values were reported for the lab method and sensors, their uncertainty could not be calculated.

Figure 12 shows the results for the seven oils according to the ISO standard: each test diagram reports the trends of the codes assigned to the oil in each of the three-dimensional classes “<4 μm”, “<6 μm”, and “<14 μm”. It can be noticed that, in the diagrams, the ISO code values provided by

S4 do not correspond to integers, but decimal numbers. This depends on the fact that, as said in “

Section 2.7—Data collection and analysis”, all sensors’ data used in the comparison with Lab-data represented the averages of all daily measurements. The comparison between Lab-data and

S4-data was possible only for

A and

B. In the relating diagrams we can observe that in all dimensional classes the curves of Lab-data are higher than those of

S4: in the class “<4 μm”, the curves of laboratory and of

S4 almost overlay; in the classes “<6 μm” and “<14 μm”, the distance progressively increases, which means a lower sensibility of

S4 towards bigger particles. However, all curves of the tests with oils

A and

B start from higher contamination values and follow similar decreasing trends, testifying the effectiveness of the filtration system of the test rig. Such decreasing trends are similar to the trends of the electric conductivity in the same oils (

Figure 9). This suggests the possibility of a link between the particulate and the electric conductivity, given the absence of variations in other parameters potentially affecting the latter (e.g., TAN, PV, or RH). Such a link could be verified by investigating the nature of the particulate.

Figure 12.

Trends of the ISO 4406:2021 particle contamination codes provided by lab analyses (for the oils A and B only) and by S4 (for all seven oils).

Figure 12.

Trends of the ISO 4406:2021 particle contamination codes provided by lab analyses (for the oils A and B only) and by S4 (for all seven oils).

Despite said differences among the levels of the measurements, the test of Pearson applied to the paired data of laboratory and

S2 (

Table 17) confirmed the strong (

r > 0.6) or very strong (

r > 0.8) correlation between their trends. The values of “

p” resulted always lower than 0.05 except for the oil

A, in the class “>6 μm” (

p = 0.103) and the oil

B in the class “>14 μm” (

p = 1.126).

Figure 12 also reports the diagrams of the levels of contamination provided by

S4 in the tests with

C,

D1,

D2,

E1, and

E2 where, in general, they remained stable and lower than in

A and

B, except for

E1, which started from higher contamination levels in the three-dimensional classes and decreased during the test. Considering the substantially strong correlation between Lab-data and

S4-data, despite some differences in the contamination levels provided by the sensor, the latter seems capable to detect their variations and represents a useful device for in-line oil monitoring.

3.7. Ferromagnetic Particles

The results of lab determination of the iron (Fe) in the samples of the seven oils are reported in

Table 18, together with the relating sampling times. In all samples the Fe amounts were below the detection threshold of the standard method adopted.

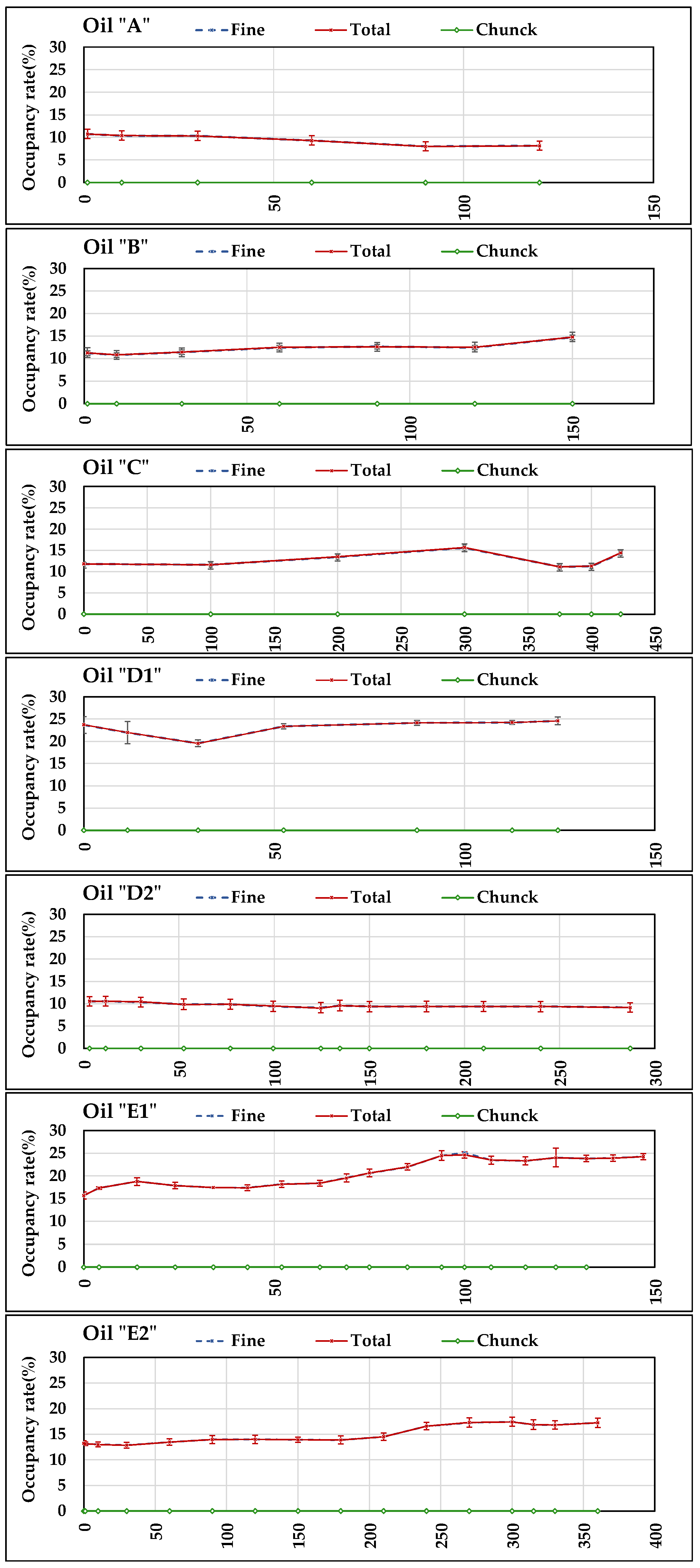

Figure 13 reports the diagrams of the daily averages of occupancy rate (fine fraction, chunk, and total) measured by

S5 in all days of tests. The accuracy of

S5 was not reported in the datasheet. However, the standard deviations of the daily measurements are reported in the diagrams. It can be noticed that all measurements relating to “fine fraction” and “total” start (at time 0 h) from values >0, which derive from the Fe particles retained by

S5 in previous tests, as explained in

Section 2.2. Therefore, the occupancy rate in each test, referred to the starting value, in general seems to be rather stable with small variations positive or negative, which mainly occurred however in the oils that were less stable relating to the other measured parameters discussed above (

A,

B,

D1, and

E1). The standard deviations values did not exceed 10% except in

D1 (second value) testifying a good stability in daily measurements. No coarse particles (chunk) were ever retained by

S5 magnetic head.

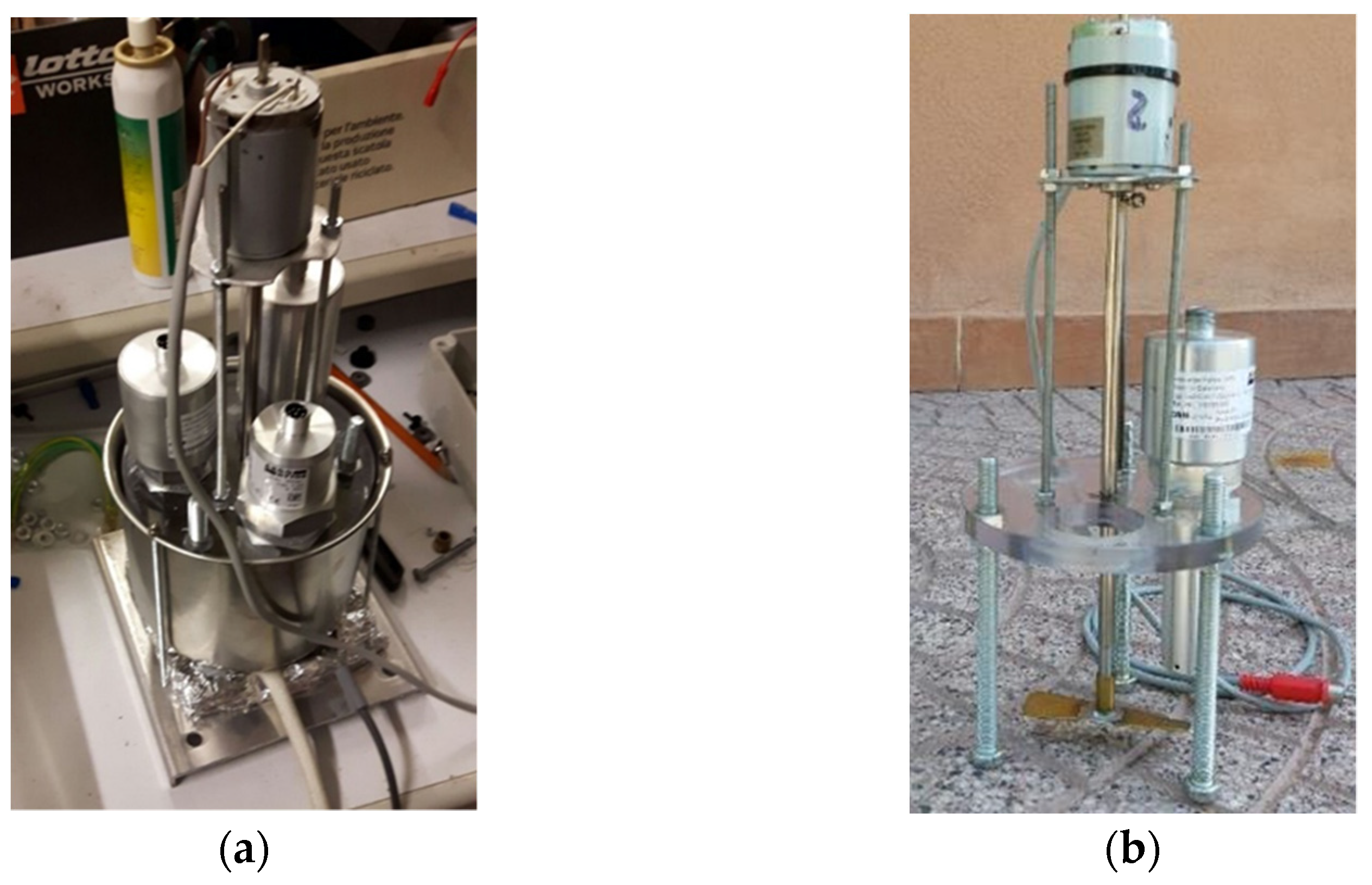

In order to clarify the meaning of such behaviour,

S5 underwent a specific test, in the equipment of

Figure 7, based on controlled conditions of Fe

2O

3 contamination of a mineral UTTO oil (density: 0.89 g mL

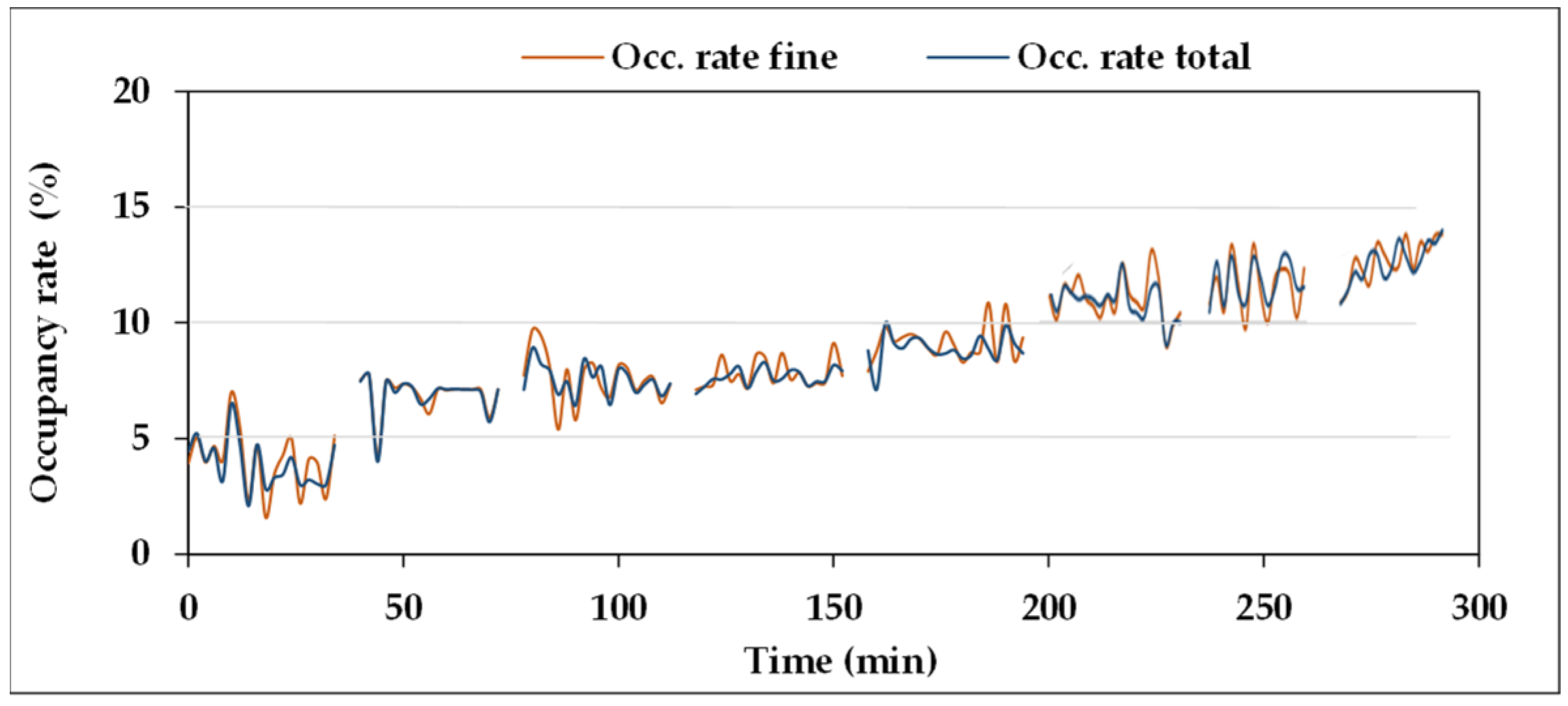

−1). The trends of the occupancy rates at seven increasing levels of Fe

2O

3 contamination are reported in

Figure 14 for “fine fraction” and “total”. Furthermore, in this case, the test started from an initial occupancy rate value >0 (about 5%), derived from previous tests, and progressively increased with further Fe additions to the oil. No chunks were detected.

The seven amounts of Fe

2O

3 powder added to the oil are reported in

Table 19, together with the total amount obtained at each step, the resulting Fe concentrations (ppm), and the averages of the occupancy rates values of the eight measurements reported in

Figure 14, both for “fine fraction” and “total”, whose values are very similar due to the absence of coarse particles to be summed to the fine fraction.

The diagram of

Figure 14 and the data reported in

Table 19 indicate that the occupancy rate increases with Fe

2O

3 concentration in the oil. The results of the test of Pearson confirm the presence of very strong correlation between the two variables, with very low “

p” values. Therefore,

S5 could effectively concur with the monitoring of the status of plants and machines, through the detection of ferromagnetic particles, preventing any damage caused by wear of some components.