Design and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS ReceiverDesign and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS Receiver

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

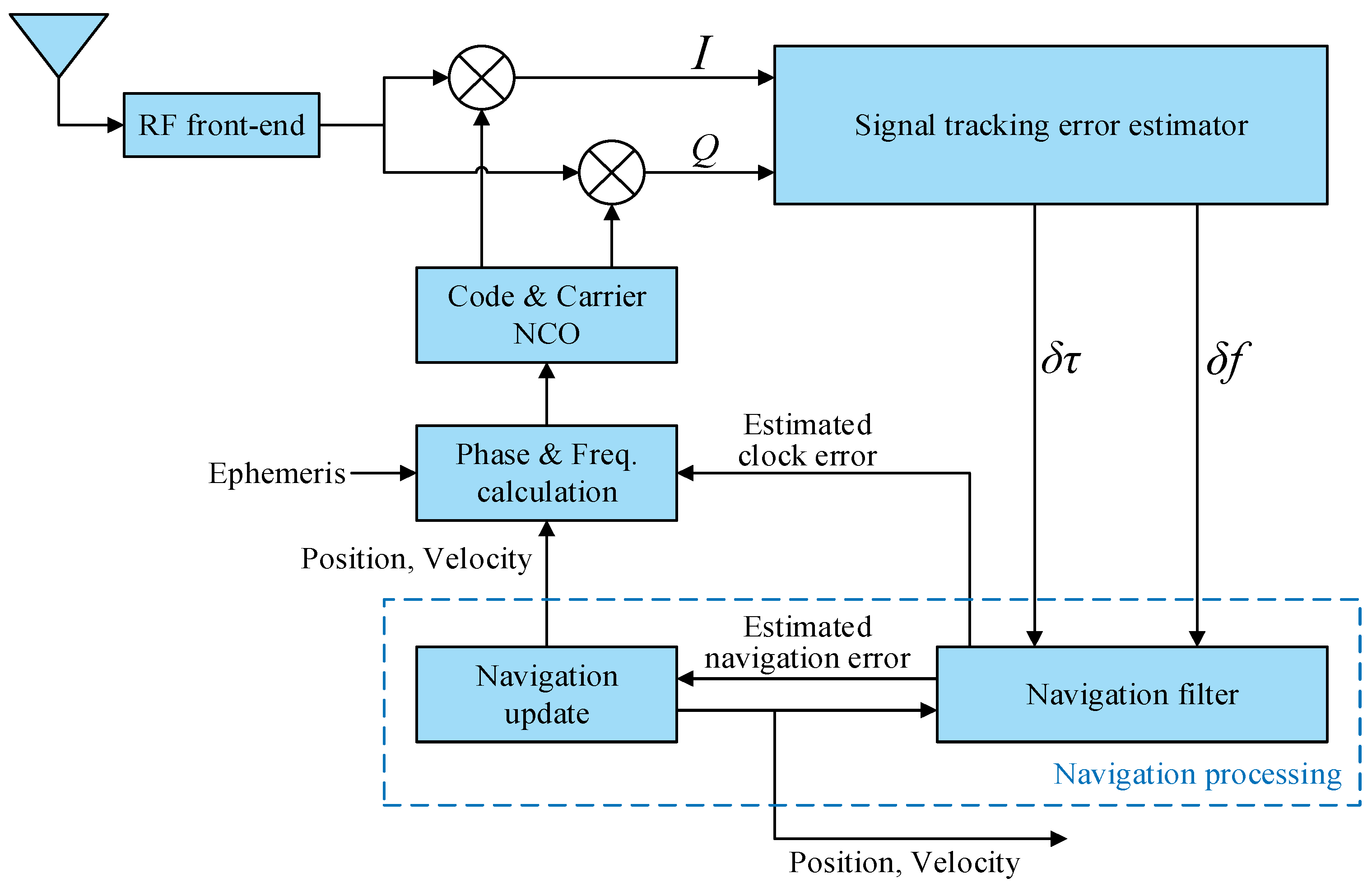

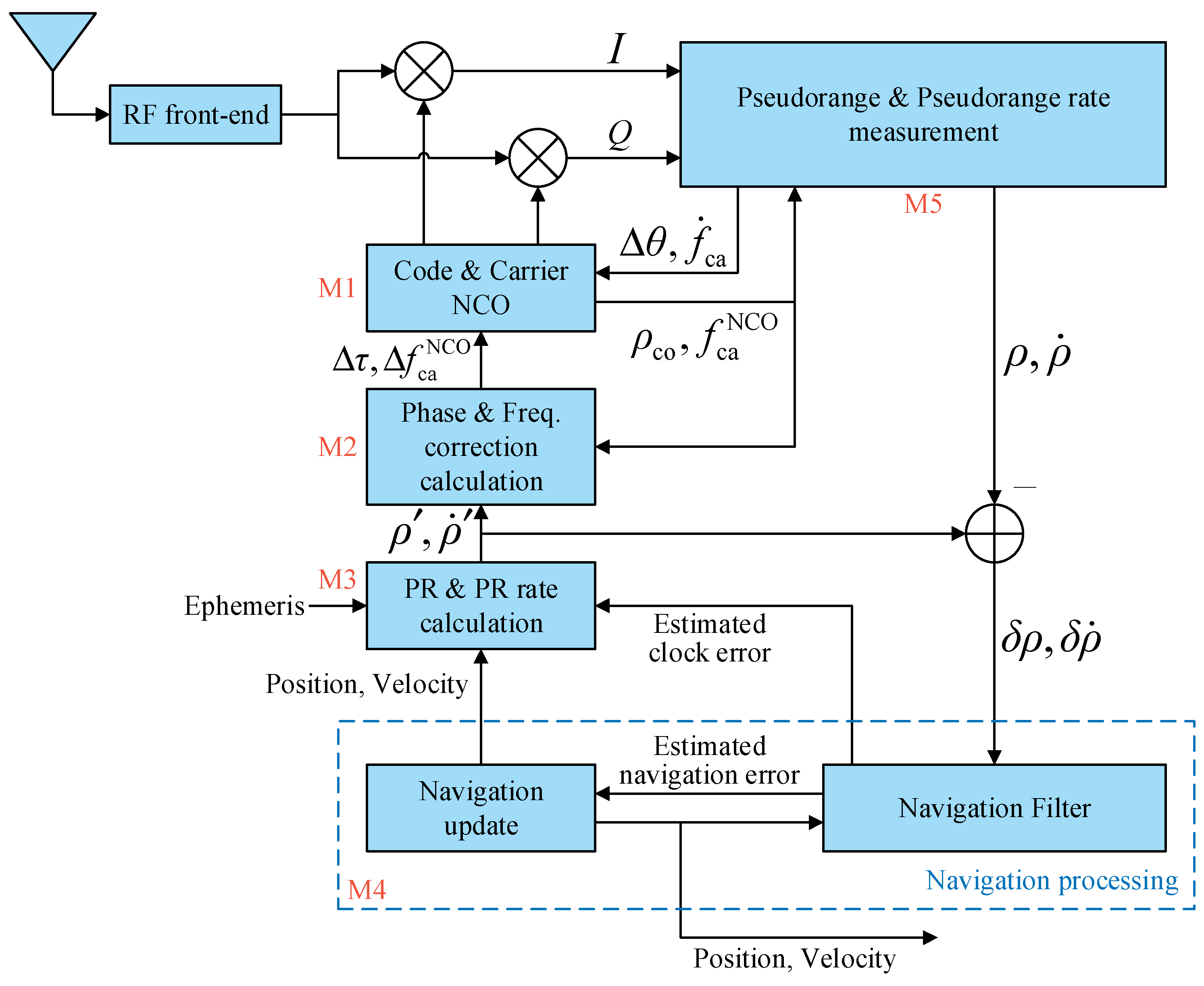

2.1. Vector Tracking Loop

2.1.1. Loop Structure

- Symbols in Figure 2:

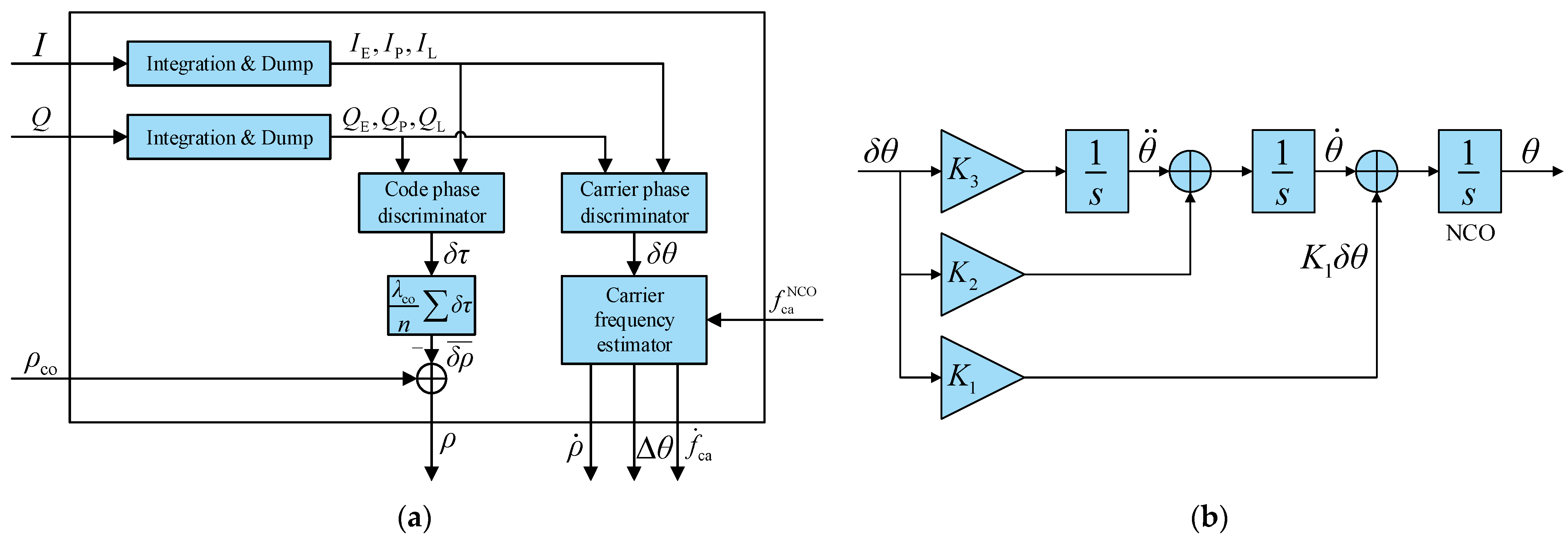

2.1.2. Pseudorange and Pseudorange Rate Measurement

2.2. Navigation Processing

2.2.1. Navigation Update

2.2.2. Navigation Filter

| Algorithm 1. Huber-based Kalman filter for the navigation filter | |

| Step 1 | Calculate one-step prediction variance matrix: . |

| Step 2 | Calculate initial state vector: , . |

| Step 3 | Calculate residual vector: , . is the number of iterations, and its initial value is 0. |

| Step 4 | Calculate Huber weight matrix: , . is Huber function, , is a parameter. |

| Step 5 | Calculate and :, . |

| Step 6 | Calculate state vector: , . |

| Step 7 | Check if is larger than a threshold. If yes, go back to Step 3. |

| Step 8 | Calculate state vector error variance matrix: . |

2.3. Weak Signal Channel Strategy

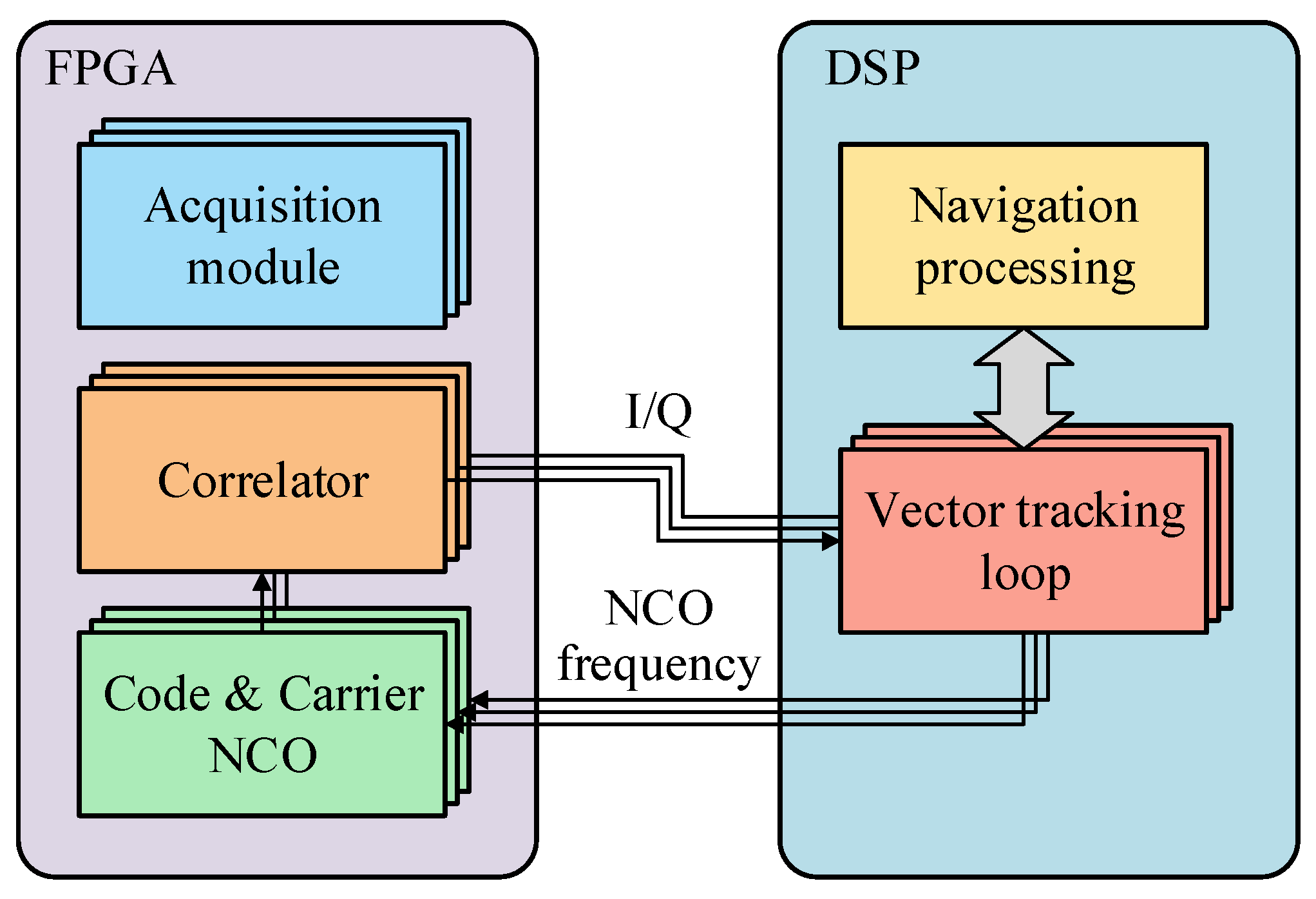

2.4. Implementation of Hardware Platform

2.4.1. Structure of Hardware Platform

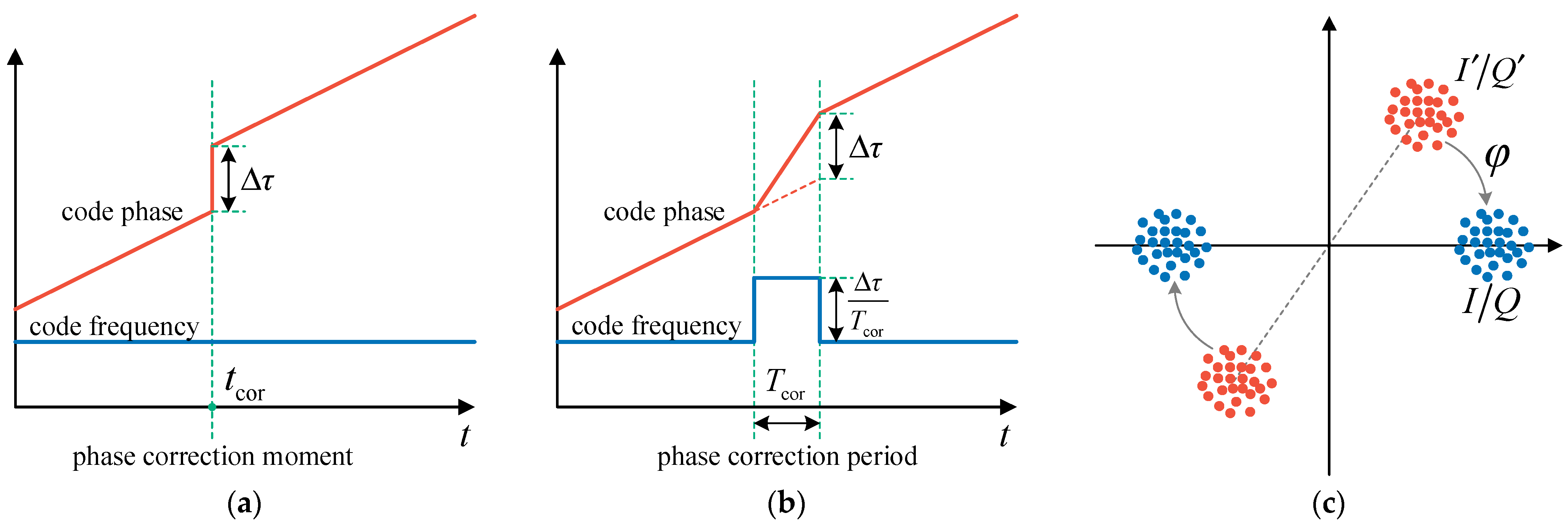

2.4.2. Code Phase Correction

2.4.3. Carrier Phase Correction

2.4.4. Time Control

2.4.5. Pseudorange Rate Measurement Synchronization

2.4.6. Workflow of Vector Receiver

3. Experiments and Results

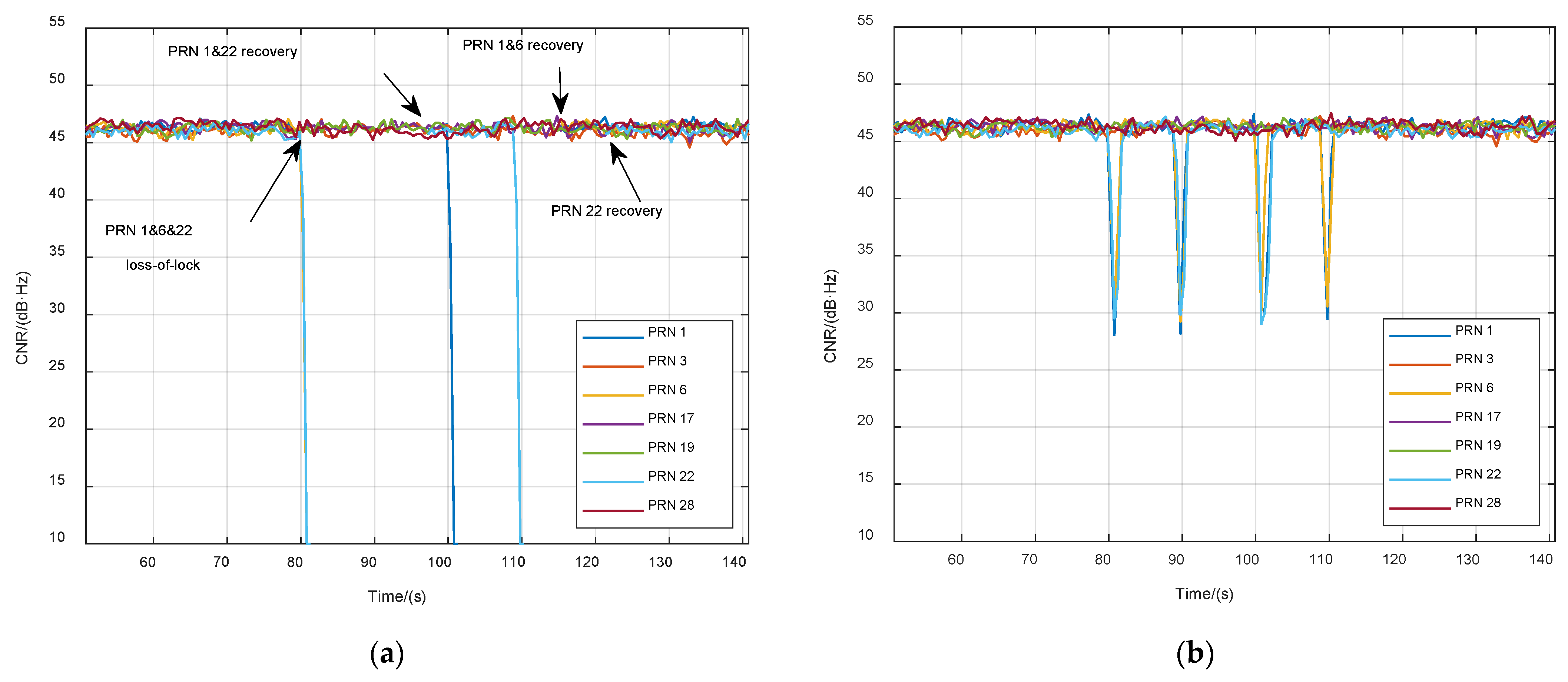

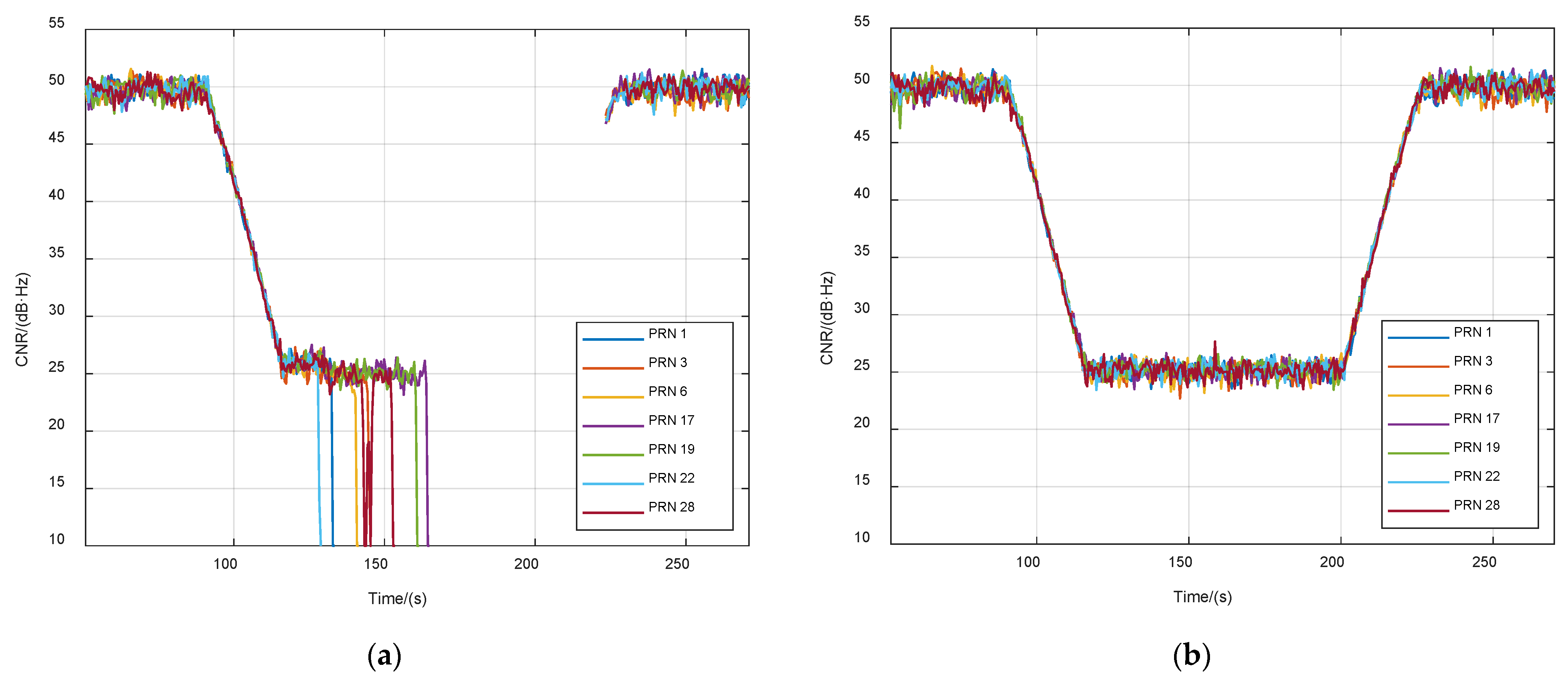

3.1. Ultrahigh-Dynamic Scenario Experiment

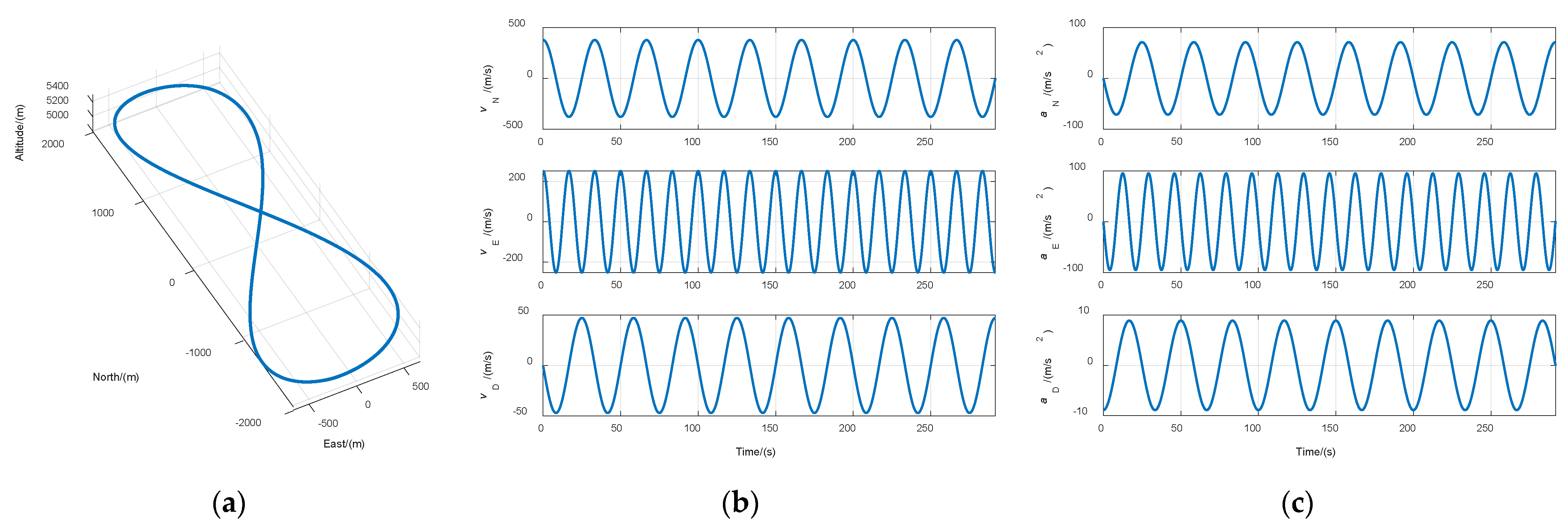

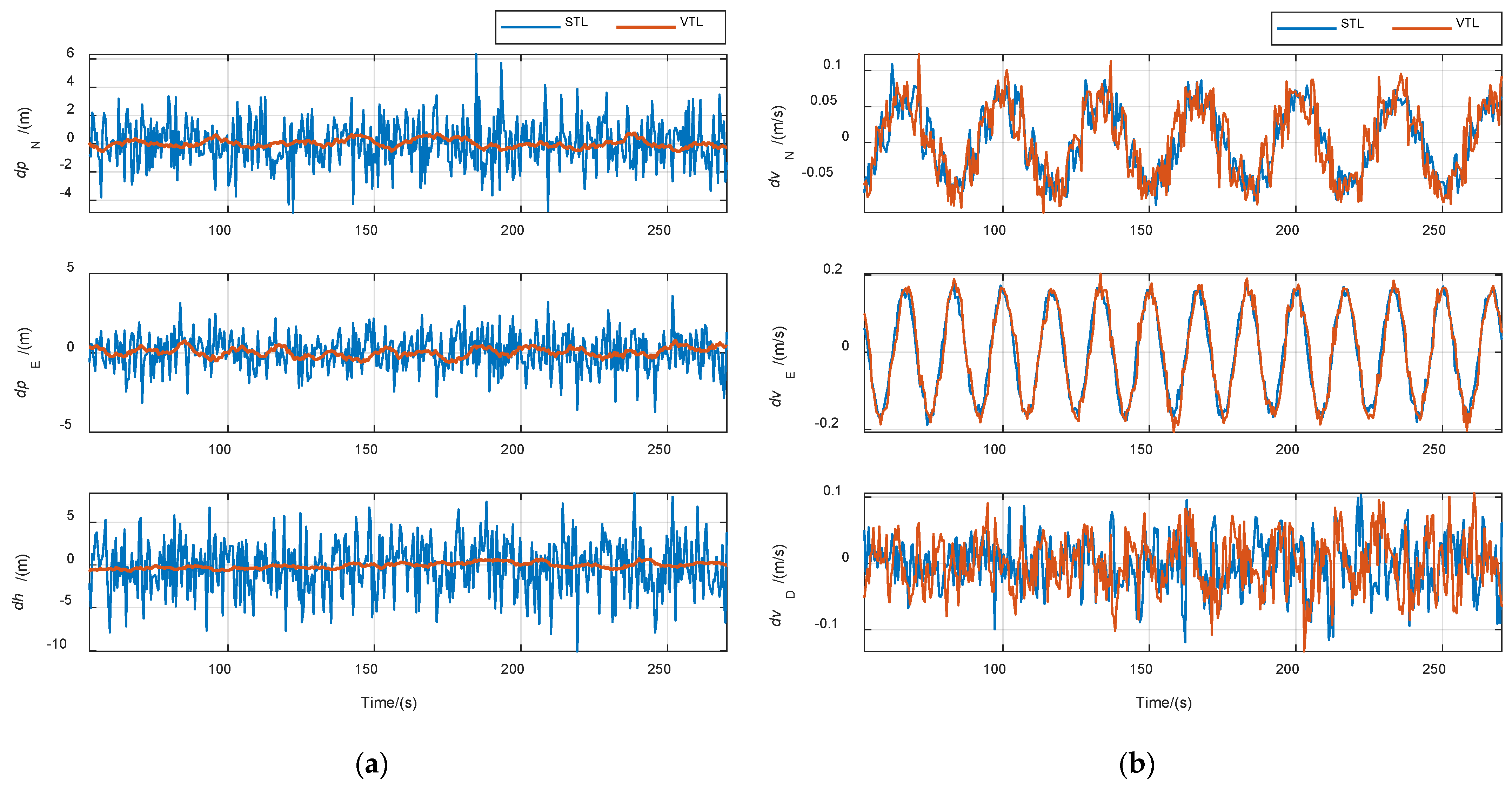

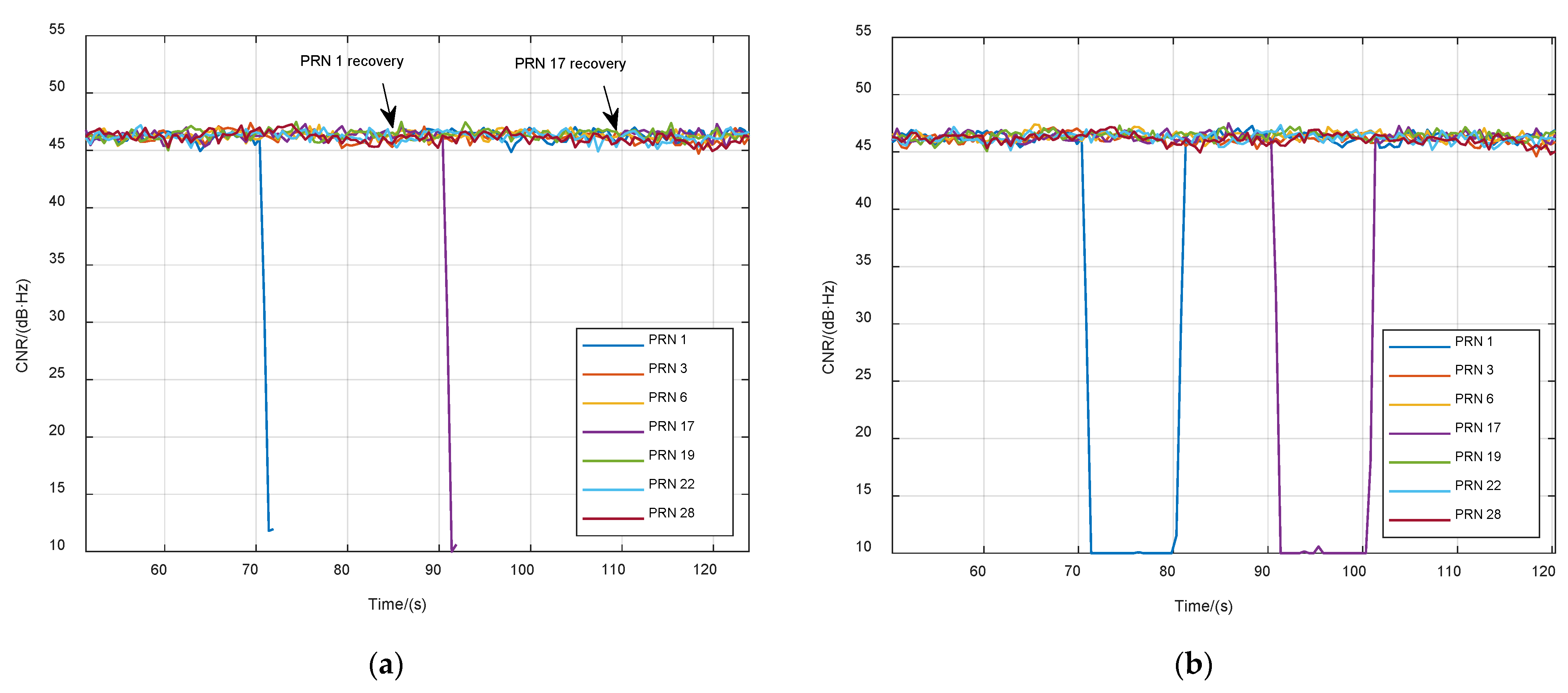

3.2. Normal High-Dynamic Scenario Experiment

3.3. Calculation Time Statistics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinedi, S.; Statman, J.I. High-Dynamic GPS Tracking Final Report; Jet Propulsion Laboratory: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, L.; Skone, S.; Raquet, J. Adaptive Antenna Arrays, Multi-GNSS Tropospheric Monitoring, and High-Dynamic Receivers. Inside GNSS 2006, 4, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, M.; Jin, T. Improvement in tracking loop threshold of high dynamic GNSS receiver by installation of crystal oscillator on gyroscopic mounting. In Proceedings of the 2015 Joint Conference of the IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium and the European Frequency and Time Forum, Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 April 2015; pp. 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shi, L.; Wang, Z. Performance analysis of a second order FLL assisted third order PLL for tracking doppler rates. WSEAS Trans. Commun. 2014, 13, 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z.; Lu, T.; Chen, Q. A Novel Carrier Loop Based on Unscented Kalman Filter Methods for Tracking High Dynamic GPS Signals. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 18th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Chongqing, China, 8–11 October 2018; pp. 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.-H.; Pany, T.; Eissfeller, B. Iterative Maximum Likelihood Estimators for High-Dynamic GNSS Signal Tracking. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 2875–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhao, J.; Long, H.; Yang, G.; Sun, J.; Yang, W. Fractional Fourier transform-based unassisted tracking method for Global Navigation Satellite System signal carrier with high dynamics. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2016, 10, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yu, C.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Ruan, H.; El-Sheimy, N. A Novel Doppler Rate Estimator Based on Fractional Fourier Transform for High-Dynamic GNSS Signal. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 29575–29596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilker, J.J., Jr.; Axelrad, P.; Parkinson, B.W.; Enge, P. Global Positioning System: Theory and Applications, Volume I; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Washington DC, USA, 1996; pp. 290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Petovello, M.G.; Lachapelle, G. Comparison of Vector-Based Software Receiver Implementations with Application to Ultra-Tight GPS/INS Integration. In Proceedings of the 19th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2006), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 26–29 September 2006; pp. 1790–1799. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Falco, G.; Falletti, E.; Presti, L.L. Performance comparison of a KF-based and a KF+VDFLL vector tracking-loop in case of GNSS partial outage and low-dynamic conditions. In Proceedings of the 2014 7th ESA Workshop on Satellite Navigation Technologies and European Workshop on GNSS Signals and Signal Processing (NAVITEC), Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 3–5 December 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.; Wang, J. Ultra-tight GPS/INS/PL integration: A system concept and performance analysis. GPS Solut. 2008, 13, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.H.; Lim, D.W.; Cho, S.L.; Lee, S.J. Unified approach to ultra-tightly-coupled GPS/INS integrated navigation system. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2011, 26, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Akos, D. An Open Source GPS/GNSS Vector Tracking Loop-Implementation, Filter Tuning, and Results. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Technical Meeting of the Institute of Navigation, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–26 January 2011; pp. 1293–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, A.S.; Lillo, W.E. Global Positioning Systems and Inertial Measuring Unit Ultratight Coupling Method. U.S. Patent US6516021, 4 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- So, H.; Lee, T.; Jeon, S.; Kim, C.; Kee, C.; Kim, T.; Lee, S. Implementation of a vector-based tracking loop receiver in a pseudolite navigation system. Sensors 2010, 10, 6324–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tu, Z.; Lou, Y.; Guo, W.; Song, W.; Wang, Y. Design and Validation of a Cascading Vector Tracking Loop in High Dynamic Environments. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T.M. A GPS and GLONASS L1 Vector Tracking Software-Defined Receiver. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, E.D.; Hegarty, C.J. Understanding GPS: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed.; Artech House: Norwood, UK, 2006; p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen, P.J.G.; Montenbruck, O. Springer Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cui, N.; Guo, J. Huber-based unscented filtering and its application to vision-based relative navigation. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2010, 4, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-H.; Lin, S.-F.; Jwo, D.-J. Robust Huber-Based Cubature Kalman Filter for GPS Navigation Processing. J. Navig. 2016, 70, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.; Grenfell, R.; Deakin, R. GPS Satellite Velocity and Acceleration Determination using the Broadcast Ephemeris. J. Navig. 2006, 59, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, B.F.; Lewis, S.W.; Brown, S.A.; Scott, T.M. Computing GPS satellite velocity and acceleration from the broadcast navigation message. NAVIGATION J. Inst. Navig. 2019, 66, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, M.S.; Weill, L.R.; Andrews, A.P. Global Positioning Systems, Inertial Navigation, and Integration; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, J.W. Binary Offset Carrier Modulations for Radionavigation. J. Inst. Navig. 2001, 48, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovaltsev, A. Antenna Arrays for Robust GNSS in Challenging Environments. In Proceedings of the International Technical Symposium on Navigation and Timing (ITSNT), Toulouse, France, 17 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Coherent integration time | This depends on signal intensity. The weaker the signal is, the longer the coherent integration time. | |

| Code and carrier NCO update period | For better tracking of high-dynamic signals, this period needs to be as small as possible, even if the coherent integration time is long. This is usually equal to the minimal integration time of the correlator, which was 1 ms on our hardware platform. | |

| Navigation update period | Theoretically, the faster the navigation update, the better. But fast navigation update has the problem of real-time computation. So, there is a trade-off to be made. Besides that, this period also depends on the hardware design. This was 50 ms on our hardware platform. |

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Before vector tracking | The receiver starts in scalar tracking mode and tracks satellite signals using conventional acquisition and tracking methods. |

| Enter vector tracking | When the number of satellites that are tracking and have ephemeris is greater than or equal to 4, the receiver enters vector tracking mode. The channels that are tracking signals are switched to use VTL. |

| Vector tracking running | Continuously acquire untracked satellites. When a new satellite is tracked, it is switched to use VTL. |

| Exit vector tracking | When the number of effective satellites (such as the CNR is larger than 23 dB·Hz) is less than 4 for a period of time, the navigation filter becomes untrusted, and the receiver exits vector tracking mode and returns to scalar tracking for a new working cycle. |

| Parameter | Value | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| STL | Bandwidth of 2nd-order DLL | 2 | Hz |

| Bandwidth of 3rd-order PLL | 18 | Hz | |

| Coherent integration time * | 1/5/20 | ms | |

| Loss-of-lock threshold | 18 | dB·Hz | |

| VTL | Bandwidth of 3rd-order carrier frequency estimator | 18 | Hz |

| Coherent integration time * | 1/5/20 | ms | |

| Navigation update period | 50 | ms | |

| Loss-of-lock threshold | 18 | dB·Hz | |

| 0 | m2 | ||

| 0 | (m/s)2 | ||

| 1002 | (m/s2)2 | ||

| 0 | m2 | ||

| † | 0.32 | (m/s)2 |

| STL | 1.68 | 1.17 | 3.21 | 0.047 | 0.115 | 0.039 |

| VTL | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.051 | 0.120 | 0.042 |

| Number of Satellites | Average Calculation Time/(ms) |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1.3 |

| 6 | 2.6 |

| 8 | 4.7 |

| 10 | 8 |

| 12 | 12.8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mu, R.; Long, T. Design and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS ReceiverDesign and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS Receiver. Sensors 2021, 21, 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21165629

Mu R, Long T. Design and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS ReceiverDesign and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS Receiver. Sensors. 2021; 21(16):5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21165629

Chicago/Turabian StyleMu, Rongjun, and Teng Long. 2021. "Design and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS ReceiverDesign and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS Receiver" Sensors 21, no. 16: 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21165629

APA StyleMu, R., & Long, T. (2021). Design and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS ReceiverDesign and Implementation of Vector Tracking Loop for High-Dynamic GNSS Receiver. Sensors, 21(16), 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21165629