Surface Functionalization of Exposed Core Glass Optical Fiber for Metal Ion Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Synthesis and Fiber Fabrication

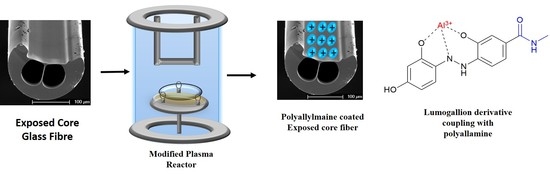

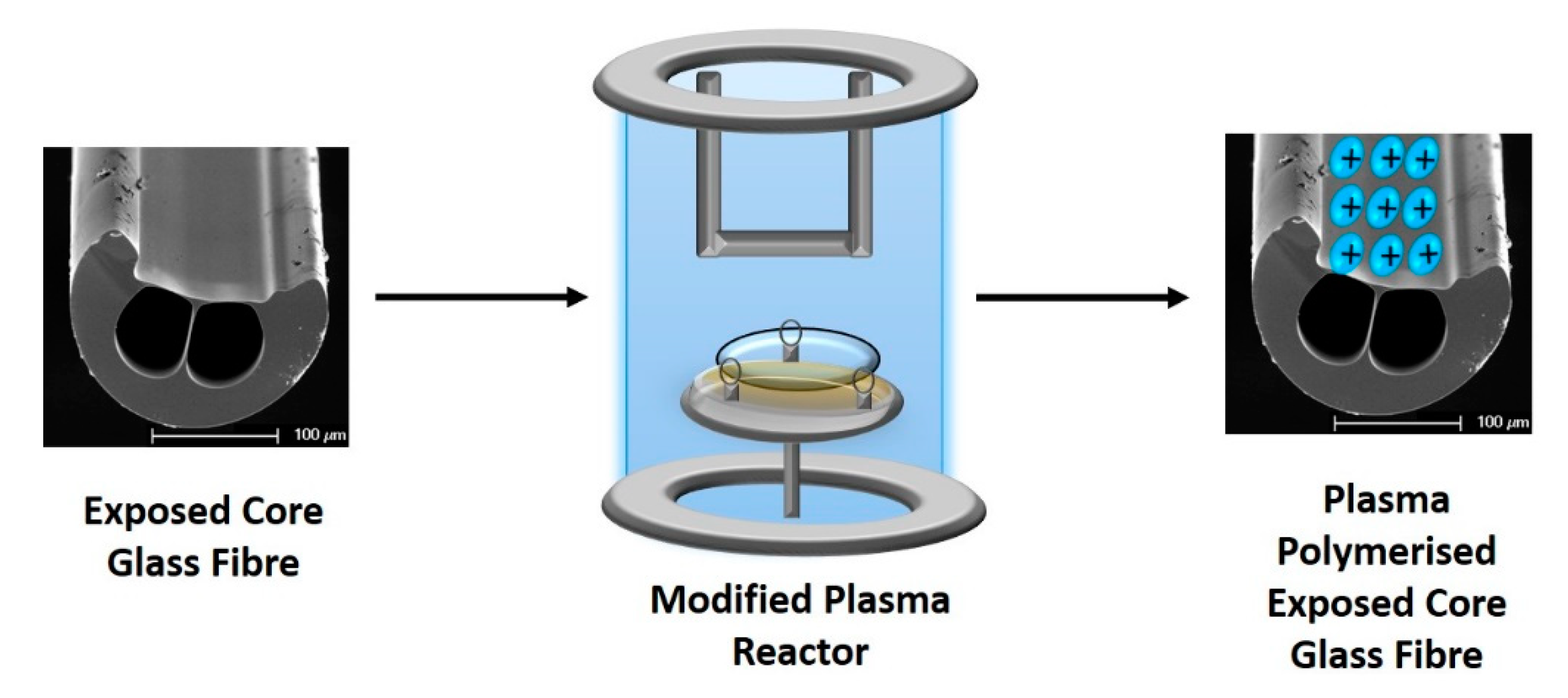

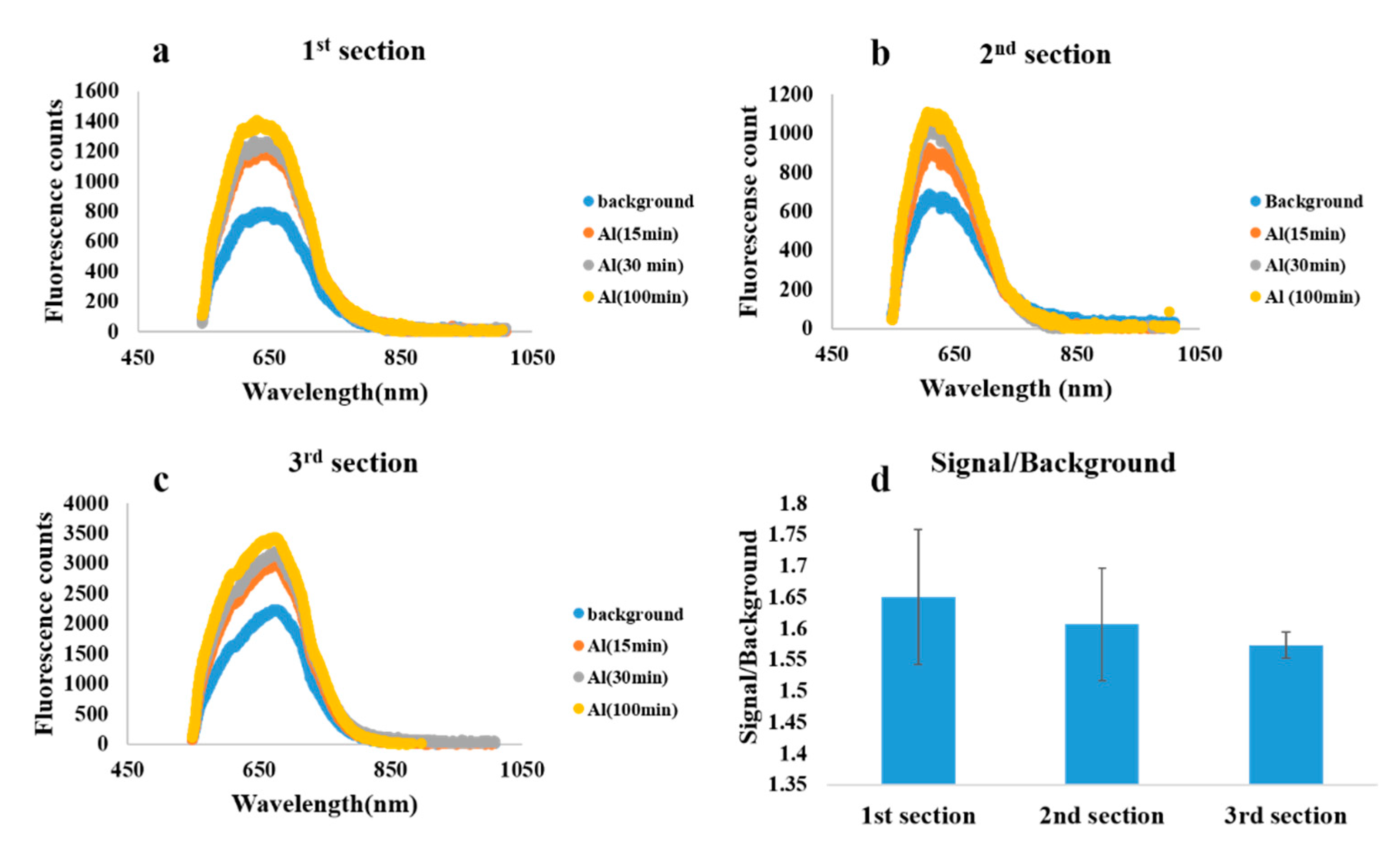

2.2. Plasma Polymerization

2.3. Immobilization of Lumogallion Derivative on ECF

2.4. Fluorescence Measurements

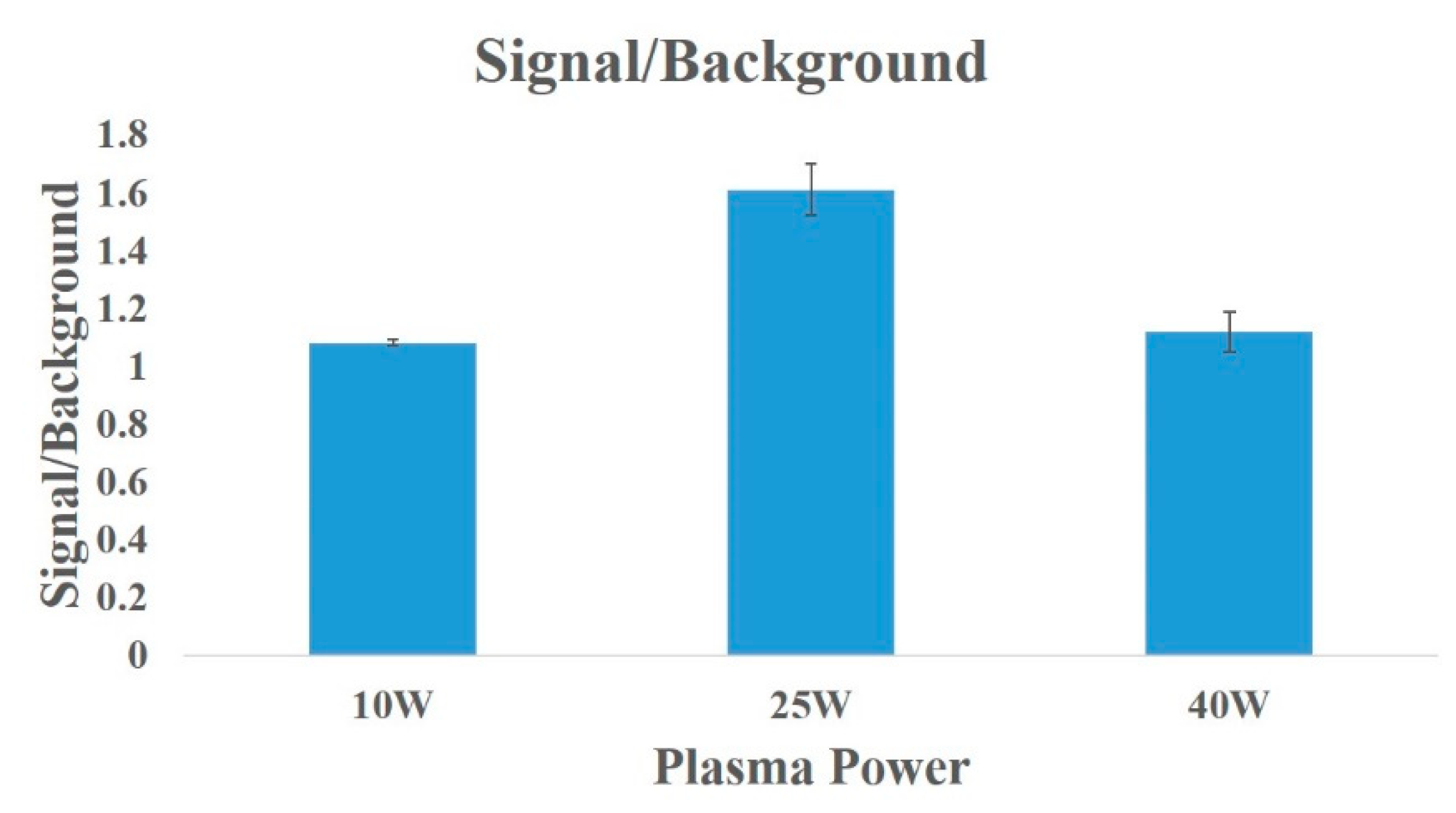

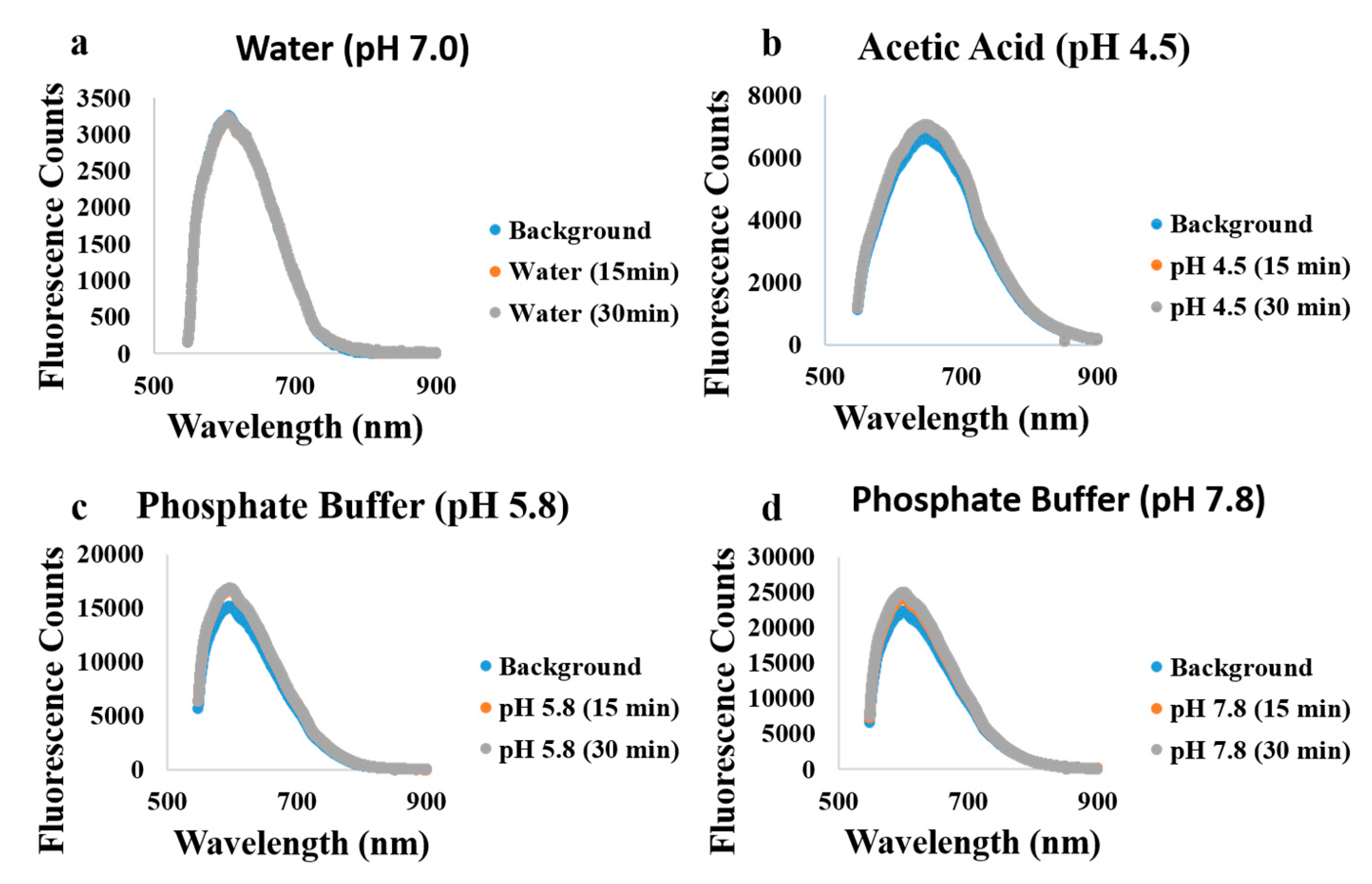

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chasapis, C.T.; Loutsidou, A.C.; Spiliopoulou, C.A.; Stefanidou, M.E. Zinc and Human Health: An Update. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, A.M.; Vaquero, M.P. Silicon, Aluminium, Arsenic and Lithium: Essentiality and Human Health Implications. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2002, 6, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ščančar, J.; Milačič, R. Aluminium Speciation in Environmental Samples: A Review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 386, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, E.; Collingwood, J.; Khan, A.; Korchazkina, O.; Berthon, G.; Exley, C. Aluminium, Iron, Zinc and Copper Influence the In Vitro Formation of Amyloid Fibrils of Aβ_ {42} in a Manner which may have Consequences for Metal Chelation Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2004, 6, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, B.; Taylor, S. The High Throughput Assessment of Aluminium Alloy Corrosion Using Fluorometric Methods. Part I–Development of a Fluorometric Method to Quantify Aluminium Ion Concentration. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyrailo, R.A.; Hobbs, S.E.; Hieftje, G.M. Near-Ultraviolet Evanescent-Wave Absorption Sensor Based on a Multimode Optical Fiber. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Narayanaswamy, R. Optical Fibre Al (III) Sensor Based on Solid Surface Fluorescence Measurement. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2002, 81, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, G.; Newman, P.; McKenzie, I.; Davis, C.; Hinton, B. Fiber Optic Sensors for Detection of Corrosion within Aircraft. Struct. Health Monit. 2005, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Smith, S.C.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Foo, T.C.; Moore, R.; Davis, C.; Monro, T.M. Exposed-Core Microstructured Optical Fibers for Real-Time Fluorescence Sensing. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 18533–18542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schartner, E.P.; Tsiminis, G.; François, A.; Kostecki, R.; Warren-Smith, S.C.; Nguyen, L.V.; Heng, S.; Reynolds, T.; Klantsataya, E.; Rowland, K.J.; et al. Taming the light in microstructured optical fibers for sensing. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2015, 6, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.C.; Birks, T.A.; Russell, P.S.J.; Atkin, D.M. All-Silica Single-Mode Optical Fiber with Photonic Crystal Cladding. Opt. Lett. 1996, 21, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monro, T.M.; Richardson, D.; Bennett, P. Developing Holey Fibres for Evanescent Field Devices. Electron. Lett. 1999, 35, 1188–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monro, T.M.; Belardi, W.; Furusawa, K.; Baggett, J.C.; Broderick, N.; Richardson, D. Sensing with Microstructured Optical Fibres. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren-Smith, S.C.; Heng, S.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Abell, A.D.; Monro, T.M. Fluorescence-Based Aluminum Ion Sensing Using a Surface-Functionalized Microstructured Optical Fiber. Langmuir 2011, 27, 5680–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostecki, R.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Davis, C.; McAdam, G.; Warren-Smith, S.C.; Monro, T.M. Silica Exposed-Core Microstructured Optical Fibers. Opt. Mater. Express 2012, 2, 1538–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecki, R.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Warren-Smith, S.C.; McAdam, G.; Davis, C.; Monro, T.M. Optical Fibres for Distributed Corrosion Sensing—Architecture and Characterisation. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 558, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Gibson, B.C.; Greentree, A.D.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Jia, P.; Kostecki, R.; Liu, G.; Orth, A.; Ploschner, M.; et al. Perspective: Biomedical sensing and imaging with optical fibers—Innovation through convergence of science disciplines. APL Photonics 2018, 3, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. The Potential Role of Aluminium in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17 (Suppl. 2), 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, D.C.; Lukiw, W.; Kruck, T. New Evidence for an Active Role of Aluminum in Alzheimer’s Disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1989, 16, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H. Cell Biology of Aluminum Toxicity and Tolerance in Higher Plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000, 200, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Piñeros, M.A.; Kochian, L.V. The Role of Aluminum Sensing and Signaling in Plant Aluminum Resistance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Gaurav, S.S.; Kumar, A. Molecular Basis of Aluminium Toxicity in Plants: A Review. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.R.; Hu, Q.; Baimpos, T.; Kristiansen, K.; Israelachvili, J.N.; Valtiner, M. Real-Time Monitoring of Aluminum Crevice Corrosion and Its Inhibition by Vanadates with Multiple Beam Interferometry in a Surface Forces Apparatus. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, C327–C332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecki, R.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Davis, C.; McAdam, G.; Wang, T.; Monro, T. Fiber Optic Approach for Detecting Corrosion. In Proceedings of the SPIE Smart Structures and Materials + Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 20–24 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, S.; McDevitt, C.A.; Kostecki, R.; Morey, J.R.; Eijkelkamp, B.A.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Monro, T.M.; Abell, A.D. Microstructured Optical Fiber-based Biosensors: Reversible and Nanoliter-Scale Measurement of Zinc Ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 12727–12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostecki, R.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Afshar, S.V.; McAdam, G.; Davis, C.; Monro, T.M. Novel Polymer Functionalization Method for Exposed-Core Optical Fiber. Opt. Mater. Express 2014, 4, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelmore, A.; Martinek, P.; Sah, V.; Short, R.D.; Vasilev, K. Surface Morphology in the Early Stages of Plasma Polymer Film Growth from Amine-Containing Monomers. Plasma Processes Polym. 2011, 8, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, K.; Michelmore, A.; Griesser, H.J.; Short, R.D. Substrate influence on the initial growth phase of plasma-deposited polymer films. Chem. Commun. 2009, 28, 3600–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Keudell, A.; Benedikt, J. A physicist’s perspective on “views on macroscopic kinetics of plasma polymerisation”. Plasma Processes Polym. 2010, 7, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, K.K. A chemical engineering perspective on “Views on macroscopic kinetics of plasma polymerisation”. Plasma Processes Polym. 2010, 7, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinsch, C.L.; Chen, X.; Panchalingam, V.; Eberhart, R.C.; Wang, J.-H.; Timmons, R.B. Pulsed radio frequency plasma polymerization of allyl alcohol: Controlled deposition of surface hydroxyl groups. Langmuir 1996, 12, 2995–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelmore, A.; Steele, D.A.; Whittle, J.D.; Bradley, J.W.; Short, R.D. Nanoscale deposition of chemically functionalised films via plasma polymerisation. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 13540–13557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubing, D.B.; Heng, S.; Monro, T.M.; Abell, A.D. A comparative study of the fluorescence and photostability of common photoswitches in microstructured optical fibre. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 239, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruiz, J.C.; Taheri, S.; Michelmore, A.; Robinson, D.E.; Short, R.D.; Vasilev, K.; Förch, R. Approaches to Quantify Amine Groups in the Presence of Hydroxyl Functional Groups in Plasma Polymerized Thin Films. Plasma Processes Polym. 2014, 11, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, K.; Britcher, L.; Casanal, A.; Griesser, H.J. Solvent-Induced Porosity in Ultrathin Amine Plasma Polymer Coatings. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 10915–10921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilev, K.; Michelmore, A.; Martinek, P.; Chan, J.; Sah, V.; Griesser, H.J.; Short, R.D. Early Stages of Growth of Plasma Polymer Coatings Deposited from Nitrogen-and Oxygen-Containing Monomers. Plasma Processes Polym. 2010, 7, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bachhuka, A.; Heng, S.; Vasilev, K.; Kostecki, R.; Abell, A.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H. Surface Functionalization of Exposed Core Glass Optical Fiber for Metal Ion Sensing. Sensors 2019, 19, 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19081829

Bachhuka A, Heng S, Vasilev K, Kostecki R, Abell A, Ebendorff-Heidepriem H. Surface Functionalization of Exposed Core Glass Optical Fiber for Metal Ion Sensing. Sensors. 2019; 19(8):1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19081829

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachhuka, Akash, Sabrina Heng, Krasimir Vasilev, Roman Kostecki, Andrew Abell, and Heike Ebendorff-Heidepriem. 2019. "Surface Functionalization of Exposed Core Glass Optical Fiber for Metal Ion Sensing" Sensors 19, no. 8: 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19081829

APA StyleBachhuka, A., Heng, S., Vasilev, K., Kostecki, R., Abell, A., & Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H. (2019). Surface Functionalization of Exposed Core Glass Optical Fiber for Metal Ion Sensing. Sensors, 19(8), 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19081829