Abstract

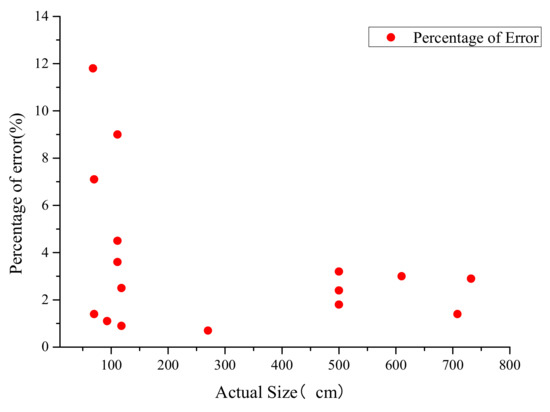

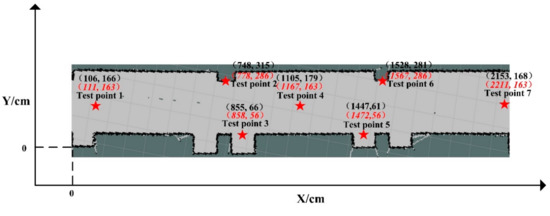

Due to hot toxic smoke and unknown risks under fire conditions, detection and relevant reconnaissance are significant in avoiding casualties. A fire reconnaissance robot was therefore developed to assist in the problem by offering important fire information to fire fighters. The robot consists of three main systems, a display operating system, video surveillance, and mapping and positioning navigation. Augmented reality (AR) goggle technology with a display operating system was also developed to free fire fighters’ hands, which enables them to focus on rescuing processes and not system operation. Considering smoke disturbance, a thermal imaging video surveillance system was included to extract information from the complicated fire conditions. Meanwhile, a simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) technology was adopted to build the map, together with the help of a mapping and positioning navigation system. This can provide a real-time map under the rapidly changing fire conditions to guide the fire fighters to the fire sources or the trapped occupants. Based on our experiments, it was found that all the tested system components work quite well under the fire conditions, while the video surveillance system produces clear images under dense smoke and a high-temperature environment; SLAM shows a high accuracy with an average error of less than 3.43%; the positioning accuracy error is 0.31 m; and the maximum error for the navigation system is 3.48%. The developed fire reconnaissance robot can provide a practically important platform to improve fire rescue efficiency to reduce the fire casualties of fire fighters.

1. Introduction

Fire casualties occur not only for occupants but also for firefighters. Recently, many firefighters have lost their lives during fire rescuing processes. A statistical study [1] indicated that 742 firefighters were killed in the U.S. during 2006–2014, while the average deaths were 73 during 2011– 2016 [2]. One of the main reasons is because of the unknown and hazardous fire environment with toxic gases, high temperature, dense smoke, and low amount of oxygen [3,4].

One of the major challenges for fire rescue is detection, such as fire location, temperature and smoke density, and the available route. The accuracy of the detection not only determines the selection of rescue plan but also the result of the selected rescue plan [5]. It is crucial for the firefighters to clearly understand the relevant information under complicated fire conditions before entering the building. Normally, fire detection includes external inspection, consulting the evacuees from the fire, and internal detection. The external inspection is very much based on the experience of firefighters but they usually can only obtain limited information, such as based on flame type, direction, the color and smell of smoke, and movement characteristics. Consultation with the escapers from a fire usually lacks accuracy as the evacuees are quite stressful after escaping from the fire and the fire scenarios are also changing all the time.

Among these three methods, internal detection may be currently the most direct one for firefighters. Before entering the building, firefighters should be equipped with a breathing device, oriented rope, high-power flashlight, etc. However, the acquirement of the information is limited by the carried oxygen cylinder and flashlight. Moreover, the firefighters are always under high risk. Based on the above analysis, it is critically important to develop a fire reconnaissance robot to overcome the problems mentioned above.

A large number of studies have been carried out regarding the development of a fire robot. Based on their equipped devices and functions, these robots can be further divided into four types, namely auxiliary rescue robot, inspection robot, fire suppression robot, and reconnaissance robot. An auxiliary rescue robot is designed to assistant firefighters regarding their walking, transport of devices, and fire suppression. For example, Li et al. [6] developed a walking assist device based on a modified ultrasonic obstacle avoidance technology. Figure 1 shows a robot, called Longcross [7], which can follow the firefighters and offer assistance under fire conditions. It can help to transport occupants and devices under emergency conditions, and also suppress fire together with the firefighters. Another example is Octavia [8], which is a humanoid robot that is equipped with a fire extinguisher. It can suppress fire together with firefighters and also clear obstacles with control of gesture and voice.

Figure 1.

Firefighter follower robot called Longcross.

The inspection robot aims to inspect the specified areas under fire conditions, which can also suppress the fire independently. For example, Sucuoglu et al. [9] designed an obstacle avoidance robot equipped with smoke, temperature and flame sensors, which can detect the fire within 1 m with an accuracy of 92%. SAFFiR [10] is a humanoid firefighting robot, which can avoid obstacles on a ship, maintain balance, and walk upright. It can control a fire extinguisher even though it is not directly equipped with firefighting equipment. Alhaza et al. [11] designed an indoor firefighting robot equipped with fire extinguisher. It can detect the fire source based on flame detection technology and firefighters can confirm the fire from a camera and then take the relevant actions. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is another type of fire inspection. It shows excellent maneuverability and a broad working area, which can be adopted for aerial inspection and suppression of early-stage fire [12].

A fire suppression robot is used to suppress the fire through remote control of the firefighters. For example, Zhang and Dai [13] designed a remotely controllable robot that is able to replace firefighters in the hazardous areas for rescuing processes. Another robot, called JMX-LT50 [14], is equipped with a high-pressure water jet, where a camera on it is used to assist the remote control of a water jet. Figure 2 shows a firefighting robot, called LUF60 [15]. The high-power nozzle equipped in LUF60 can spray water in the form of water mist that can reduce the ambient temperature in a short time, move the toxic gases away, change the direction of smoke movement, and broaden the view during the rescuing process.

Figure 2.

A firefighting robot called LUF60.

A reconnaissance robot is a type of robot mainly focusing on fire inspection. Its function is on passing important fire information to fire fighters but not direct fire suppression. For example, Kim et al. [16] developed an intelligent firefighting mobile robot. The robot is equipped with an obstacle avoidance function, which can find the fire source and plan the path to it through an infrared camera. Berrabah [17] designed a reconnaissance robot for the outdoor environment, which is equipped with GPS, inertial navigation, cameras, ultrasonic sensors, and various chemical sensors while the obtained information can be transferred to the control center for decision making.

Although many types of robots have been introduced above, the development of a firefighting robot is still at its starting stage. Several challenges and shortcomings still exist: (a) most of the firefighting robots focus on fire suppression, ignoring the detection in the surrounding environment. So their volume is quite big, which limits their mobility and applicability; (b) The function of mapping construction for the robots is hampered under the fire conditions. Although they are equipped with the original map of the building, they lack real-time mapping construction as the map could be changed quite significantly under fire conditions; (c) The controller of the robots is quite heavy so that it is inconvenient to carry. Therefore, the robot needs to be standing still to enable the relevant operation. It cannot free the hands of the firefighters, which limits the capability of their rescuing tasks, as shown in Figure 2.

Therefore, to overcome the above challenges, a small and flexible robot was developed for fire reconnaissance in this study, with the functions of operation display, map construction, and video monitoring. It enables the monitoring and operation of the robot based on AR technology, real-time map construction under fire conditions based on SLAM technology, and fire detection and rescuing based on the infrared thermos image technology and video surveillance system.

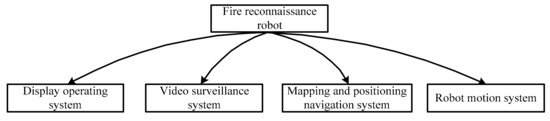

2. Description of the Robot System

For a robot dedicated to environmental reconnaissance, the video surveillance system is an indispensable part that can provide extensive information through images. Considering the complexity of the indoor environment, the mapping and positioning navigation system can then offer important support to firefighters to quickly reach the target position. Also, the display operation equipment carried by firefighters is an important part of a fire reconnaissance robot. Therefore, based on the above considerations, the developed fire reconnaissance robot in this study contains several systems, including a display operating system, a video surveillance system, a mapping, and positioning navigation system, and a motion system. The detailed structure of the developed robot can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The structure of the developed fire reconnaissance robot.

2.1. Display Operation System

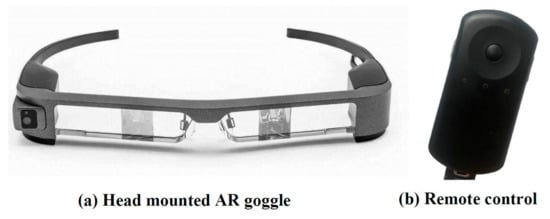

To free the hands of the firefighters, the display operation system was developed based on the currently most advanced AR goggle technology (e.g., EPSON BT300, as shown in Figure 4). The goggle uses two 4.3-inch high-definition silicon OLEDs as the projection unit, which is equivalent to an 80-inch screen displayed in front of the firefighters. The resolution is as high as 1280 × 720, which can provide very comprehensive and clear images.

Figure 4.

EPSON BT300.

EPSON BT300 (Epson (China) Co., Ltd. Beijing, China) is equipped with remote control, as shown in Figure 4b. It is equipped with an Android 5.1 processing system, Intel Atom x 5 CPU, 2 GB RAM, and 48 G memory. It also adopts a touch sensor so that the control can be based on inputs such as touch and drag.

2.2. Video Surveillance System

When compared with other scenarios, the requirements of the video surveillance system for fire conditions is much higher. Due to the attenuation of smoke on the light, ordinary cameras cannot be applied under fire conditions. To solve the problem, a thermal imaging camera is usually adopted to construct the video surveillance system. In this study, the thermal imaging camera was supplied by Zhejiang Dahua Technology in China (DH-TPC-BF5400), as shown in Figure 5. The system uses uncooled Vox infrared focal plane array, where the thermal imaging detector pixel is 400 × 300, and the imaging resolution is as high as 1280 × 1024. The system shows the advantages of low energy consumption, which enable 24 h of uninterrupted working.

Figure 5.

Thermal imaging camera DH-TPC-BF5400.

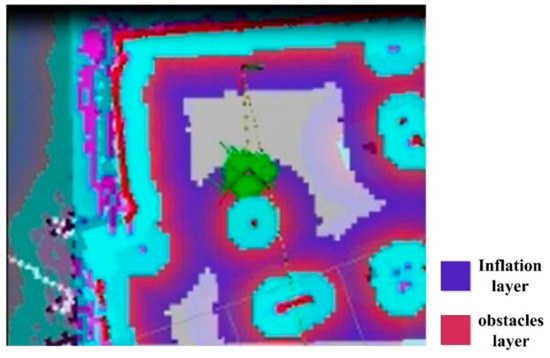

2.3. Mapping and Positioning Navigation System

The mapping and positioning are based on technologies, such as AutoCAD map, ultra-wide band (UWB), wireless local area network (WLAN), Bluetooth, radio frequency identification (RFID), and ZigBee [18]. However, under fire conditions, the original map may be not applicable due to the collapse of walls or structural components under fire conditions. At the same time, the base station for the systems may encounter power failure and is not able to offer continuing support [19,20]. Therefore, a real-time mapping and positioning navigation system may be the best solution currently under fire conditions.

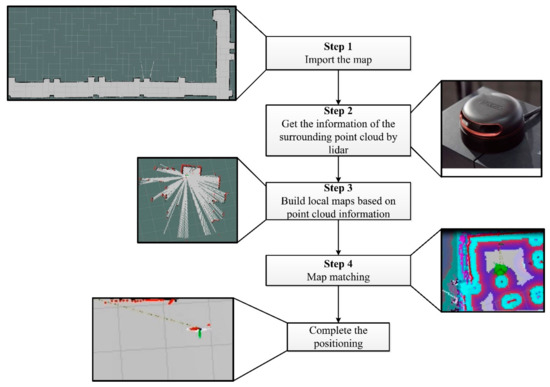

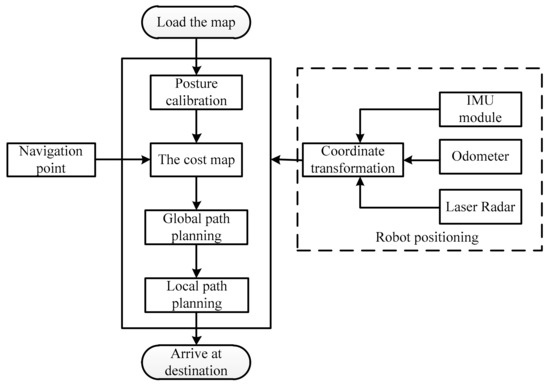

Based on the above analysis, a mapping and positioning navigation system was developed based on a SLAM technology. The advantage is that the map can be built in real time that does not rely on AutoCAD maps. There is also no need to pre-arrange additional infrastructure such as the base station. It can be seen from Table 1 that the SLAM technology does not require support from base station and shows high positioning accuracy. Due to the above-mentioned advantages, the developed system is suitable for the fire environment.

Table 1.

Technical parameters of commonly adopted indoor positioning technology.

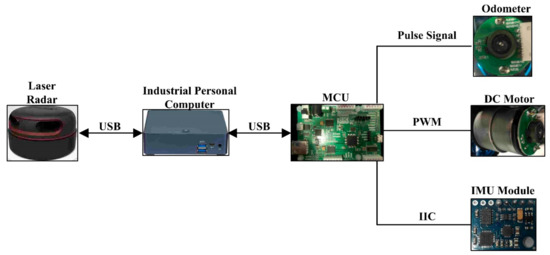

Laser SLAM technology refers to a technique where the robot uses its own sensor to realize positioning during movement in an unexplored environment, and to inspect the surrounding environment to construct an incremental mapping to realize the positioning and navigation. The related hardware can be seen in Figure 6. Light detection and ranging (LiDAR, RPLIDAR-A2, SLAMTEC, shanghai, China) was adopted as the core detection unit to scan the surrounding area based on laser triangulation technology and to detect 2D point cloud information at the surfaces of the surrounding obstacles. The related information is then used to construct the map in an industrial personal computer (IPC) based on the SLAM algorithm. The technical parameters for the LiDAR are listed in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Hardware for the positioning and navigation of SLAM (MCU (microcontroller unit); DC Motor (Direct-Current Motor); IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit)).

Table 2.

The main technical parameters of the adopted LiDAR (RPLIDAR-A2).

Inertial measurement unit (IMU, GY-85, ADI, Norwood, America) was also adopted to collect the gesture information, such as walking speed and yaw. Also, an odometer was used to obtain the distance information of the walking robot. A microcontroller unit (MCU, STM32F103, STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) was adopted to transfer the information to the IPC for post-processing. The movement of the robot is then realized by the DC motor driven by the MCU.

The robot has a problem in that the data collected by the sensor includes data of noise and measurement failure in the process of map construction. The problem will have a great impact on the accuracy of map construction because this system has uncertainty and external interference [21]. To solve this problem, Du et al used Kalman filters (KFs) and particle filters (PFs) to fuse the sensor data, thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of the system [22,23]. Therefore, in this research, the motion system of the robot is modeled by analyzing the data of the odometer, this model is regarded as the nonlinear model of the extended KFs. Then, the collected data of the odometer, IMU and LIDAR are respectively taken as the observation quantity and observation covariance matrix for status update, so as to obtain the updated system state and system covariance matrix. Finally, the updated state quantity and covariance matrix are the attitude information of the robot itself. The current position of the robot is estimated through the PFs to determine the position of the robot in the map.

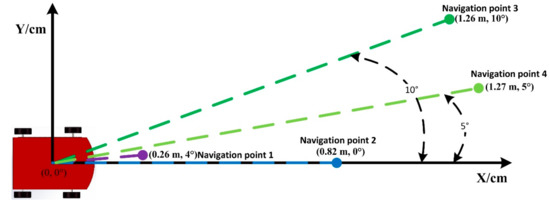

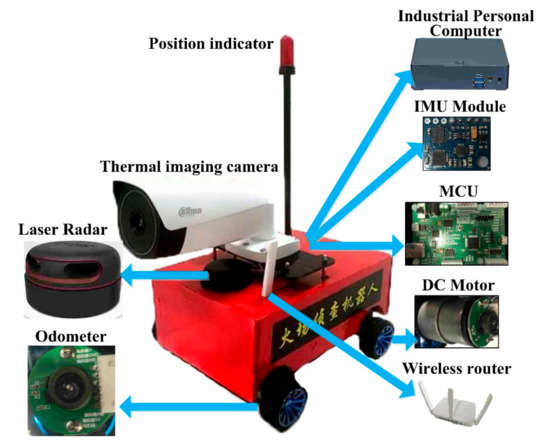

2.4. The Overall Fire Reconnaissance Robot System

For the overall operation of the developed fire reconnaissance robot through this study please refer to Figure 7. Under fire conditions, the firefighters with AR goggles can follow the robot, while the firefighters do not need to carry anything as all the hardware can be placed on the robot, as shown in Figure 8. The robot is equipped with a router, and AR goggle and can communicate with the robot through a WIFI signal to acquire information such as video and map. Based on the communication, the robot can be controlled when it is within 50 m. The dimension of the robot is 30 cm (L) × 29 cm (W) × 30 cm (H), which can be driven by four 12 V DC motors. It has the advantages of small volume, excellent mobility, and applicability.

Figure 7.

The operation of the developed fire reconnaissance robot.

Figure 8.

The structure of the developed fire reconnaissance robot (MCU (microcontroller unit); DC Motor (Direct-Current Motor); IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit)).

3. Performance Test of the Video Surveillance System

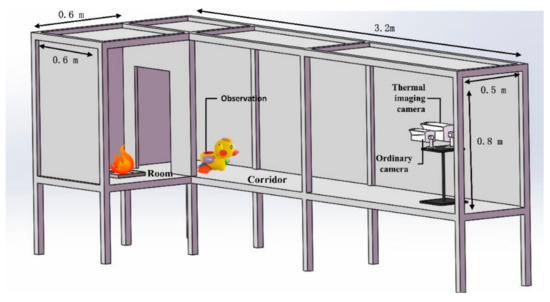

To address the applicability of the thermal imaging camera under fire conditions, an experimental model was developed to simulate the typical fire scenario, as shown in Figure 9. The experimental model includes a room connected to a corridor, while the fire source is located inside the room. The dimension of the room is 0.6 m × 0.6 m × 0.8 m (H), while for the corridor it is 3.2 m (L) × 0.5 m (W) × 0.8 m (H). The produced smoke inside the room can spread to the corridor through the door between them.

Figure 9.

Experimental model to simulate a typical fire scenario with both room and corridor.

To test the performance of the video surveillance system, a color duck was adopted. Experimental results between the thermal imaging camera and ordinary camera were also compared. The ordinary camera was purchased from the same company with a thermal imaging camera, namely Zhejiang Dahua Technology in China. The ordinary camera is equipped with both visible and infrared imaging functions, where the infrared function can be automatically turned on when the ambient environment is dark. The fire source adopted typically n-heptane together with a smoke cake with ammonium, where the burning of the n-heptane and smoke cake can release a large amount of heat and smoke, respectively, to simulate the real fire conditions. The advantage of the combination is that it can quickly form an experimental environment with high temperature and dense smoke.

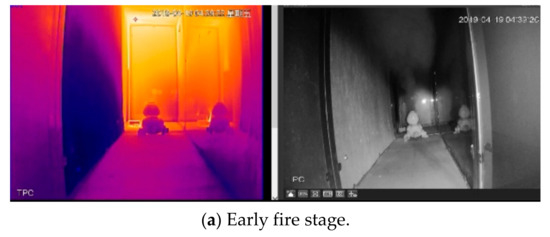

The experimental results are shown in Figure 10, while the left and right figures show the outputs from thermal imaging and ordinary cameras, respectively. After the ignition of the fire, the ordinary camera changes to the infrared mode automatically when the surrounding environment is getting dark. This is the reason why the ordinary camera shows a gray-scale image. At the beginning of the test, the areas on both sides can be reflected by the ordinary camera. However, after the smoke becomes dense, the ordinary camera is unable to provide a clear image anymore. For the thermal imaging camera, the figures stay quite clear all the time, no matter which fire stage it is. The smoke shows a limited influence on the performance of the thermal imaging camera, as shown in Figure 10b. Even after more smoke is released, the thermal imaging camera is still capable of offering a clear figure, as shown in Figure 10c). Therefore, the viability of the adopted thermal imaging camera for fire conditions can be confirmed through experimental test. It can be considered as one of the feasible solutions for the current situation.

Figure 10.

Comparisons between the obtained figures of thermal imaging and ordinary cameras under different fire stages.

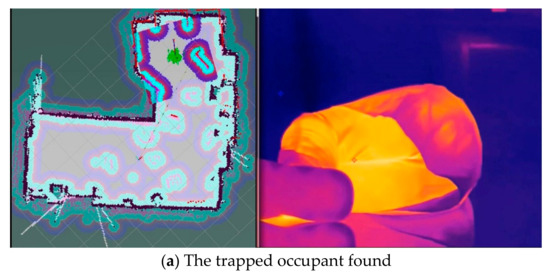

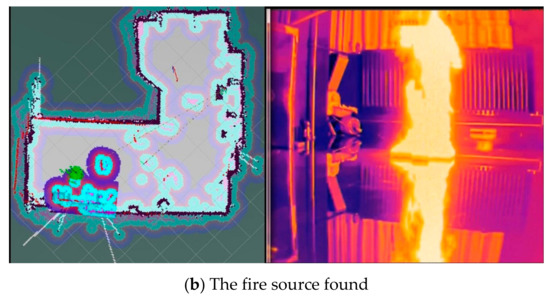

5. A Comprehensive Test under Fire Conditions

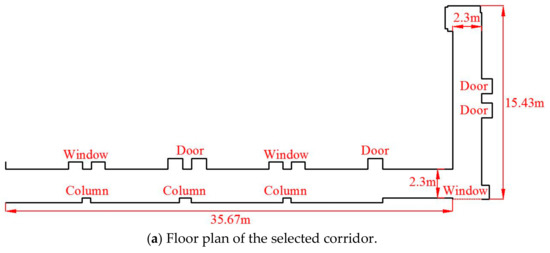

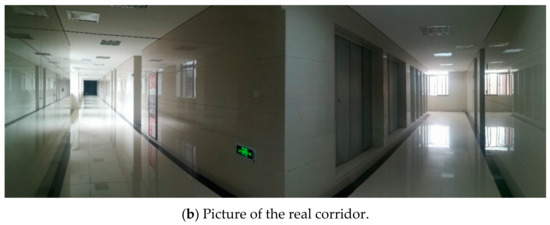

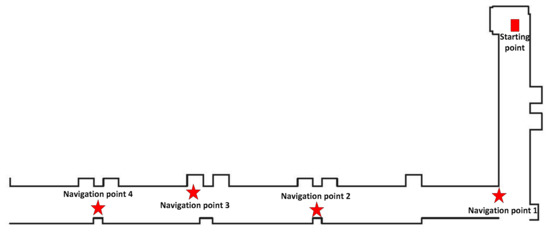

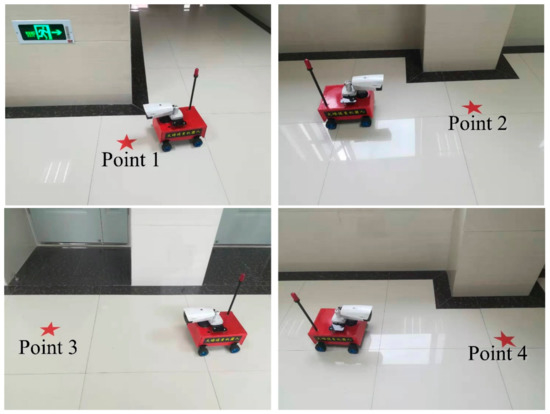

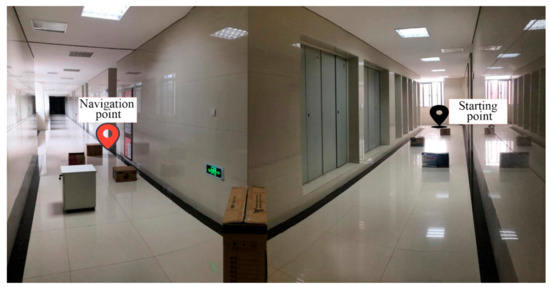

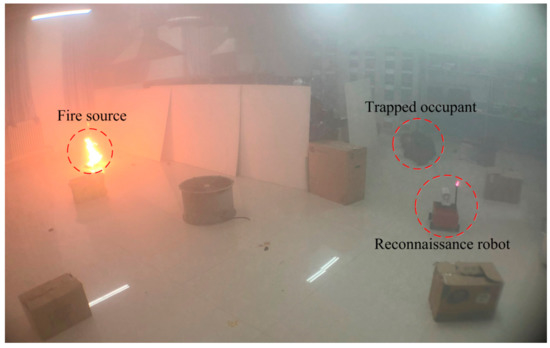

To test the viability of the developed robot in this study, a comprehensive test was undertaken under fire conditions. To simulate the fire scenario, an indoor environment was selected, while fireproof panels were adopted to construct an L-shaped area. The constructed L-shaped area was about 50 m2, as shown in Figure 26.

Figure 26.

Simulated fire scenario inside an indoor environment.

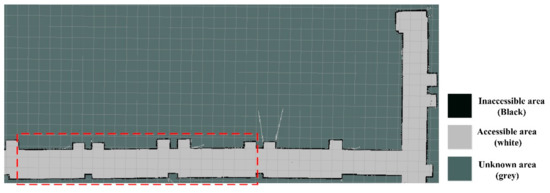

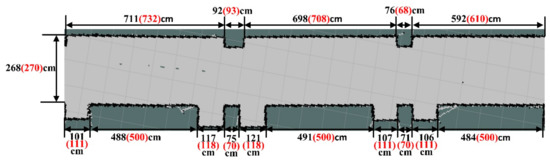

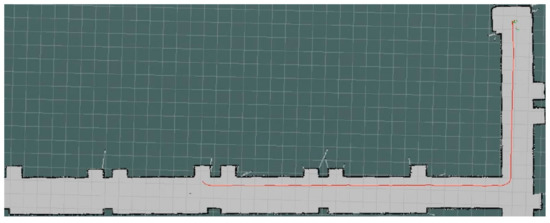

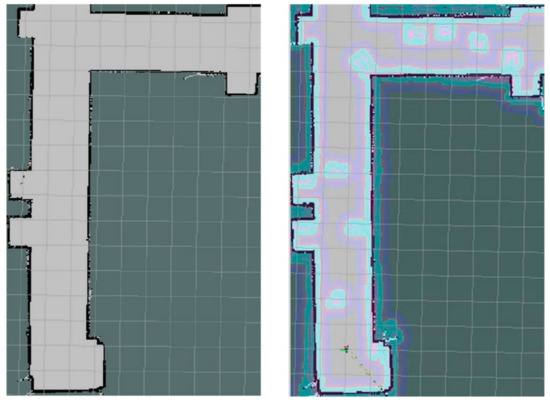

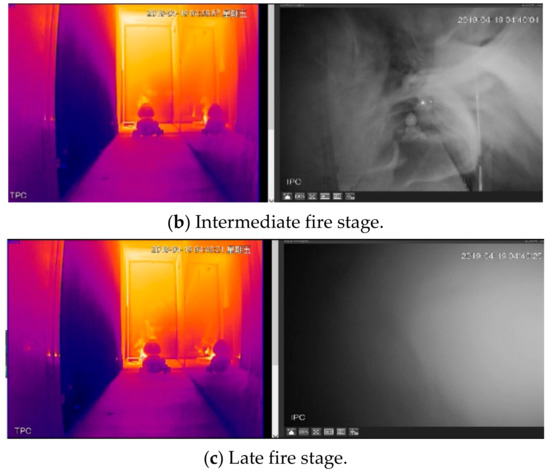

Before the experiment, the map of the experimental environment was constructed, as shown in Figure 27. Compared with Figure 26, it can be seen that the constructed map shows good reducibility when compared to the real situation.

Figure 27.

Constructed occupancy grid mapping for the simulated fire environment.

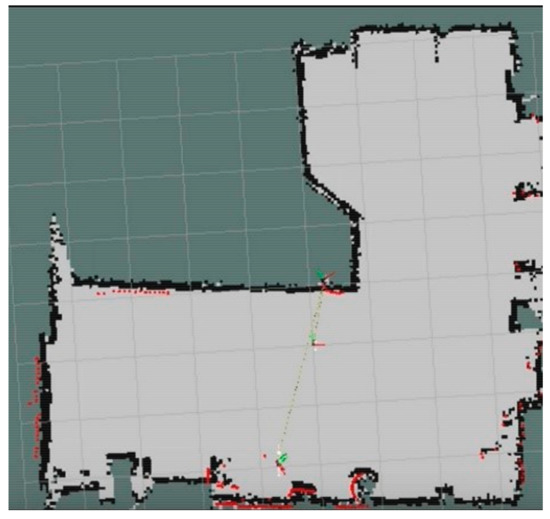

During the experiment, to be more consistent with the real fire scenario, several obstacles were positioned randomly inside the tested environment to simulate collapsed walls or other structures under fire. The performance of obstacle avoidance for the developed fire reconnaissance robot can also be tested by these obstacles. A combined n-heptane pool fire and smoke cake with ammonium at the left end of the L-shaped area was adopted to simulate a fire scenario of both high temperature and dense smoke. A volunteer lay on the floor at the right end of the L-shaped area, which was to simulate a trapped occupant under fire conditions, as shown in Figure 28.

Figure 28.

A simulated fire scenario with random obstacles, the fire source is on the left side of the L- shaped area, and a trapped occupant is on the right side of the L-shaped area. (This picture was taken at the beginning of the experiment, and the smoke completely covered the experimental environment after that).

The developed fire reconnaissance robot was positioned inside the target area. The searching function of the robot was triggered and started to search for the trapped occupant and the fire source. The results after the search are shown in Figure 29. It can be seen from this figure that the video surveillance system clearly displays the information of both occupant and flame and the positions of the occupant and flame can be easily obtained by the robot, which is significant for the rescuing processes under fire conditions. Several areas in white can also be observed from the constructed map, which shows the position and size of the obstacles. It was indicated that the robot can easily avoid the obstacles and also update the constructed map according to the acquired obstacle information during the navigation.

Figure 29.

The results of the comprehensive test under fire conditions.

6. Conclusions

A fire reconnaissance robot was developed in this study to benefit detection and rescuing processes under fire conditions. It adopts an infrared thermal image technology to detect the fire environment, uses SLAM technology to construct the real-time map, and utilizes A* and D* mixed algorithms for path planning and obstacle avoidance. The obtained information such as videos are transferred simultaneously to an AR goggle worn by the firefighters to ensure that they can focus on the rescue tasks by freeing their hands. To verify the performance of the developed robot, experimental tests were undertaken in a typical L-shaped space with both room and corridor. It was found that the robot showed a low mapping error of 3.43% and a high positioning accuracy of 0.31 m. A comprehensive test in a fire environment was simulated by an n-heptane pool fire together with an ammonium smoke cake, where the video surveillance system clearly displayed accurately the information of both trapped occupant and flame, and their positions could be easily obtained by the robot. The developed fire reconnaissance robot can enhance firefighters’ ability to understand the surrounding environment and improve their firefighting and rescuing efficiency while ensuring their safety under fire conditions.

In the next research, we will simulate a more realistic fire scenario, with a scenario testing for fire protection, system stability, and functional realization of the robot, together with attempts to increase robot data error correction capability testing, and exploring data fusion technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. (Sen Li), Y.N. and C.F.; methodology, S.L. (Sen Li), L.S. (Long Shi); software, Y.N. and C.F.; validation, L.S. (Long Shi), Z.W. and H.S.; investigation, S.L. (Sen Li), C.F., and Y.N.; data curation, Z.W. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. (Sen Li), L.S. (Long Shi); C.F., and Y.N.; writing—review and editing, S.L. (Sen Li), L.S. (Long Shi); supervision, S.L. (Sen Li) and L.S. (Long Shi).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists of China (Grant No. 51504219, 51804278), and the Key Scientific Research Projects of Universities of Henan (Grant No. 20A620005).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the foundations’ supports.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hard, D.L.; Marsh, S.M.; Merinar, T.R.; Bowyer, M.E.; Miles, S.T.; Loflin, M.E.; Moore, P.H. Summary of recommendations from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program 2006–2014. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 68, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, R.F.; LeBlanc, P.R.; Molis, J.L. Firefighter Fatalities in the United States–2016. National Fire Protection Association, July 2017, pp. 7–8. Available online: https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/ff_fat16.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Fahy, R.F.; LeBlanc, P.R.; Molis, J.L. Firefighter fatalities in the United States-2011. Emmitsburg, MD: NFPA, July 2012, pp. 4–5. Available online: https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/ff_fat11.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Karter, M.J. Fire loss in the United States during 2010. National Fire Protection Association Quincy, 1 September 2011; 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Xin, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, J.; Sun, H.; Yang, Z.; Yu, M.; Yang, J.; Cheng, L. A Fire Protection Robot System Based on SLAM Localization and Fire Source Identification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Electronics Information and Emergency Communication (ICEIEC), Beijing, China, 12–14 July 2019; pp. 555–560. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Feng, C.; Liang, X.; Qin, H. A guided vehicle under fire conditions based on a modified ultrasonic obstacle avoidance technology. Sensors 2018, 18, 4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, F.E.; Wildermuth, D. Using robots for firefighters and first responders: Scenario specification and exemplary system description. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2017 18th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), Sinaia, Romania, 28–31 May 2017; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Martinson, E.; Lawson, W.E.; Blisard, S.; Harrison, A.M.; Trafton, J.G. Fighting fires with human robot teams. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 7–12 October; pp. 2682–2683.

- Sucuoglu, H.S.; Bogrekci, I.; Demircioglu, P. Development of Mobile Robot with Sensor Fusion Fire Detection Unit. IFAC-Papers OnLine 2018, 51, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Starr, J.W.; Lattimer, B.Y. Firefighting robot stereo infrared vision and radar sensor fusion for imaging through smoke. Fire Technol. 2015, 51, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaza, T.; Alsadoon, A.; Alhusinan, Z.; Jarwali, M. New Concept for Indoor Fire Fighting Robot. Procedia–Social Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 2343–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shaffer, J.A.; Carrillo, E.; Xu, H. Hierarchal Application of Receding Horizon Synthesis and Dynamic Allocation for UAVs Fighting Fires. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 78868–78880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dai, C. Development of a new remote controlled emergency-handling and fire-fighting robot. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2009 WRI World Congress on Computer Science and Information Engineering, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 31 March–2 April 2009; Volume 7, pp. 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.F.; Liew, S.M.; Alkahari, M.R.; Ranjit, S.S.S.; Said, M.R.; Chen, W.; Rauterberg, G.W.M.; Sivakumar, D.; Sivarao. Firefighting mobile robot: state of the art and recent development. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Yu, H.; Cang, S.; Vladareanu, L. Robot-assisted smart firefighting and interdisciplinary perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2016 22nd IEEE International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC), Colchester, UK, 7–8 September 2016; pp. 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Keller, B.; Lattimer B, Y. Sensor fusion based seek-and-find fire algorithm for intelligent firefighting robot. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 9–12 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berrabah, S.A.; Baudoin, Y.; Sahli, H. SLAM for robotic assistance to fire-fighting services. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 8th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, Jinan, China, 7–9 July 2010; pp. 362–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H. Mobile Fire Evacuation System for Large Public Buildings Based on Artificial Intelligence and IoT. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 64101–64109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrero, S.; Paneda , X.G.; Melendi, D.; García, R.; Plagemann, T. Using Firefighter Mobility Traces to Understand Ad-Hoc Networks in Wildfires. IEEE Access 2017, 6, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, J.; Wang, P.; Pahlavan, K.; Ning, H.; Wang, Q. Toward Emergency Indoor Localization: Maximum Correntropy Criterion Based Direction Estimation Algorithm for Mobile TOA Rotation Anchor. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 35867–35878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Zhang, P.; Li, D. Human–manipulator interface based on multisensory process via Kalman filters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 5411–5418. [Google Scholar]

- Du, G.; Zhang, P. A markerless human–robot interface using particle filter and Kalman filter for dual robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 62, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X. Markerless human–manipulator interface using leap motion with interval Kalman filter and improved particle filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2016, 12, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Schiller, J. An indoor positioning system based on inertial sensors in smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–12 March 2015; pp. 2221–2226. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, M.; Mut, V.; Sisterna, C. Ultra wideband indoor navigation system. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2012, 6, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, R.; Xiong, H. Image-based localization aided indoor pedestrian trajectory estimation using smartphones. Sensors 2018, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Shen, C.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H.; Gao, Q.; Chen, Y. A combined GPS UWB and MARG locationing algorithm for indoor and outdoor mixed scenario. Cluster Comput. 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Tong, J. An Indoor Navigation System Based on Stereo Camera and Inertial Sensors with Points and Lines. J. Sens. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Madani, B.; Orujov, F.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R.; Venčkauskas, A. Fuzzy Logic Type-2 Based Wireless Indoor Localization System for Navigation of Visually Impaired People in Buildings. Sensors 2019, 19, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).