Small Private Key MQPKS on an Embedded Microprocessor

1. Introduction

The technology related to embedded systems has made significant progress, making many applications, such as home automation, surveillance systems and environment monitoring services, feasible. However, without secure and robust data protection from security threats, these services cannot be put into practice. To solve these problems, public key cryptography has been studied for several decades. The current main stream is Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), which is an approach based on the algebraic structure of elliptic curves over finite fields. The use of elliptic curves in cryptography was suggested independently by Koblitz [1] and Miller [2] in 1985. The technology provides a short key-size and various applications, including Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA), Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH).

The alternative multivariate quadratic (

In this paper, we study an efficient implementation of

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we give an introduction to the basic structure of Multivariate Quadratic Public Key Scheme (

2. Related Work

2.1. Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar

The idea of Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar (UOV)-signature schemes is to use a public multivariate quadratic map, , with:

In order to hide this trapdoor, secret linear transformation

The number of vinegar variables is twice the number of oil variables to make the protocol secure. The transformation involves fully mixing the oil and vinegar variables, so that malicious users cannot obtain secret values by separating the oil and vinegar variables.

2.1.1. Signature Generation

To sign a document, d, a hash function,

, is used to compute the hash value

. Next, one computes y =

2.1.2. Signature Verification

To verify the authenticity of a signature, the hash value, h, of the corresponding document and the value h′ =

2.1.3. Public Key Optimization

At CHES2011 (Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, 2011), the 0/1 UOV method for reducing the size of the public key was presented [7]. Choosing the special structure (

2.1.4. Private Key Optimization

To reduce the private key size of

2.2. Previous Implementations on Embedded Microprocessors

A software implementation of enTTS (20, 28) on a MSP 430 microprocessor was reported in [11]. The signing and verification operations were executed within 71 ms and 726 ms, respectively. At CHES2004, Yang et al. reported signs of TTS(20, 28) in 144 ms, 170 ms and 60 ms and TTS(24, 32) in 191 ms, 227 ms and 85 ms for i8032AH, i8051AH and W77E59, respectively [12]. Recently, at CHES2012, implementations of UOV, Rainbow and enTTS on an eight-bit microprocessor were reported. The author implemented

2.3. Target Platform and Tools

We used ATxmega128a1on an Xplain board as our target platform. This microprocessor has a clock frequency of 32 MHz, 128 KB flash program memory and 8 KB SRAM. Furthermore, the device provides an AES crypto-accelerator that computes the encryption within 375 clock cycles. This is significant progress compared to the software implementation of AES on the ATmega128 processor, which requires 1,993 ∼ 3,766 clock cycles [13,14] with pre-computations. In this paper, we provide a novel signature generation for modern microprocessors that uses an embedded AES accelerator for the PRNG and hash function. These approaches significantly reduce the size of the private key and optimize the computational performance, as well. To use AES module, we should trigger AES operation by following instructions as described in Algorithm 1. First, a status bit for AES operation is set. Second, a key and plain text are allocated to the AES accelerator, and then, we trigger the AES execution, which takes 375 clock cycles. During the execution, we can perform other operations using the microprocessor, because AES operations are independently executed on the AES accelerator. After the execution, we obtain the cipher-text generated from the AES accelerator by accessing the storage address. Our program is written in assembly for the main computations and partly C language for the interface. The development tool is the latest version of Atmel Studio 6.0.

| Algorithm 1: AES encryption using AES accelerator | |

| Input: Secret key k, plain text p | |

| Output: Cipher-text c | |

| 1. | AES accelerator setting |

| 2. | Move k to key storage in AES accelerator |

| 3. | Move p to plain text storage in AES accelerator |

| 4. | Execute the AES accelerator |

| 5. | Wait for completion (375 clock cycles) |

| 6. | Get c from cipher-text storage in AES accelerator |

2.4. Random Number Generator Based on a Block Cipher

Random numbers are widely used as seeds for cryptographic operations and secret key generation. Among various types of random number generators, a block cipher-based random number generator is considered in this paper to exploit the AES module in an embedded board. The following equation outlines the process of random number generation. The notations, enc, C, k and R, represent the encryption process, counter (secret seed), secret key and random number stream. First, the counter is encrypted with secret key, k. The output is then bitwise XORedwith counter value Ci, and the encryption can proceed. This process is iterated until we obtain a suitable size of random numbers.

The purpose of introducing the block cipher-based random number generator is that we will use it to generate the secret coefficients. This is possible using the AES accelerator on modern embedded boards, which can generate encrypted data conveniently. The AES accelerator is a peripheral device, so it operates independently of the microprocessor. We can order the encryption on the AES accelerator while simultaneously computing a signature on the microprocessor. This method can boost performance and reduce the required program memory. Furthermore, the PRNG process follows cipher-block chaining (CBC); this is efficiently executed using the CBC option on an embedded processor. In our implementation on ATXmega, timing and ROM cost around 40 (clock/bytes) and 204 (bytes), respectively. This result is reasonable for embedded processors. For randomness characteristic, we evaluated our random sequence on the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)-test suite [15]. Firstly we collected a pseudo random number sequence from block cipher-based PRNG by two gigabytes. Then, we operated the NIST statistical test suite version 1.6 with the number of bit streams and the length of the bit set to 100 and 1,024, respectively. The results are described in Table 1, and reasonable proportion rates are achieved.

For the security concern, the strength is based on the bit-length of block-cipher. If the inner state of the generator is compromised once, the adversary could foresee future outputs. To resolve this problem, we should compute random numbers with refreshed seed values. One possible challenge to AES in counter mode would be a timing attack on the value of the counter. We can prevent these attacks by using a counter that always takes the same amount of time to increment its value, and AES-based PRNG could give a periodic generation. This drawback could be solved by reseeding the secret values on proper timing.

2.5. Hash Function Based on a Block Cipher

Hash functions compress an input of arbitrary length to a string of fixed length. Our main motivation for constructing a hash function based on a block cipher is to minimize the design and implementation effort. The hash function based on the block cipher is conducted according to Equation (2), where H, pi, N and E denote the hash code, plain text, nonce and encryption process, respectively. This structure follows the Davies–Meyer single-block-length compression function. The security level of the one-way hash function is determined by the minimum of the size of the key and the block length [16]. To ensure a sufficient security level, we used a 128-bit secret key for the AES-based hash function.

In our hash function, we exploit the AES-accelerator for the block-cipher-based hash function. Previous

The

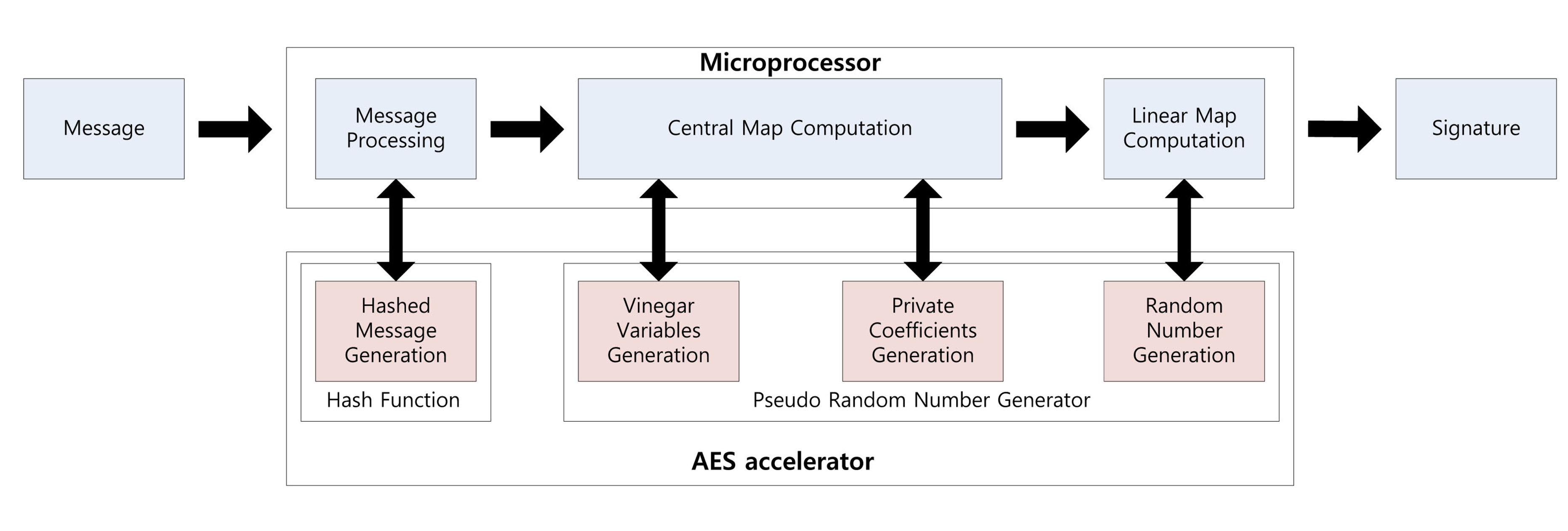

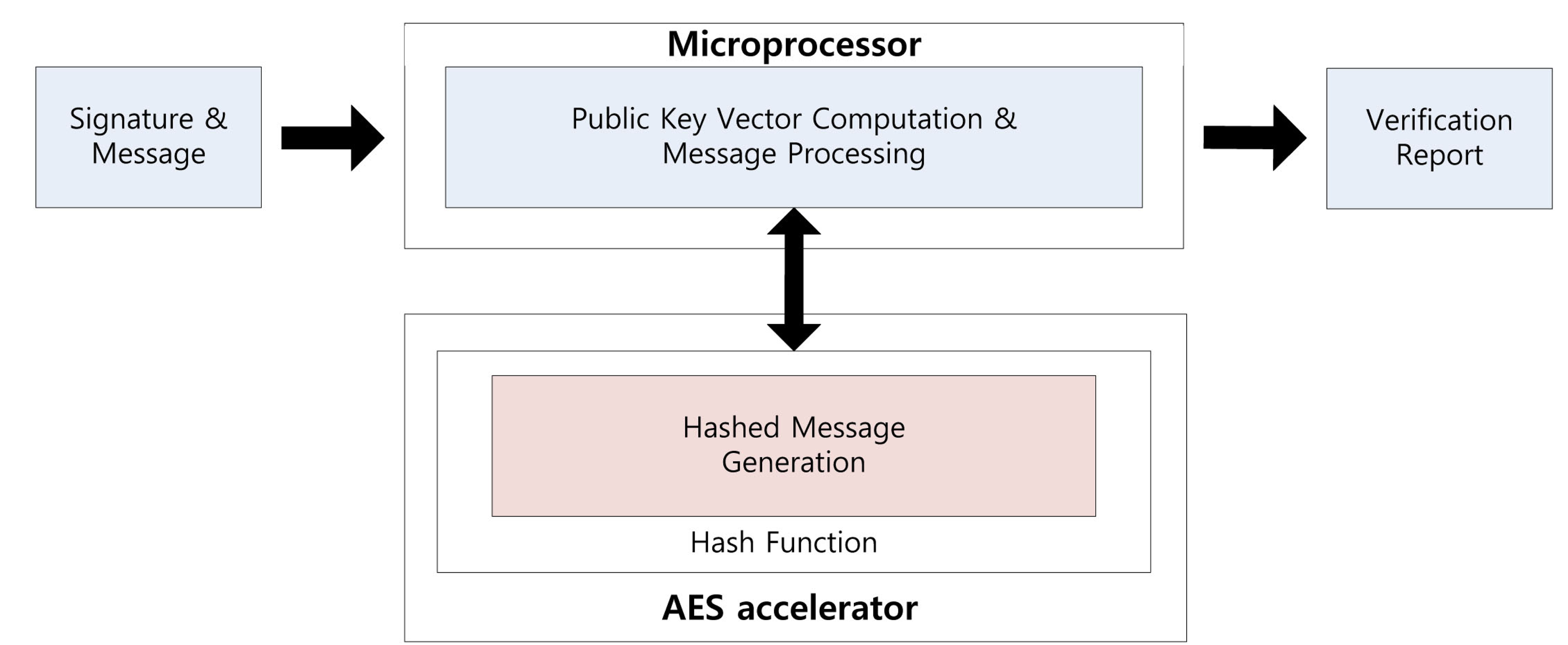

2.6. Parallel Computation

Using the parallel feature of the AES accelerator, we can compute a signature while generating the private coefficients. Signature generation on the embedded processor is described in Figure 1. First, the message is hashed using the hash function. The output is 16 bytes each time and takes 375 clock cycles. Central map computation is then executed, while vinegar variables and private coefficients are generated. These operations are conducted in independent modules, so we can compute both operations together. For this reason, we do not need any additional computation costs to generate the private coefficients. After central map computation, we generate the coefficients of the linear map. As a result of this, the overheads of the key generation process are absorbed in the central and linear map computations. This parallel computation technique can be applied to the verification process for message hashing, which is described in Figure 2. We can the conduct hash function computing the verification process, so one operation is absorbed into other operations.

3. Implementation of Small Private Key

![Sensors 14 05441i1]() PKS

PKS

3.1. Logarithm Representation

Multiplication and inversion operations on GF(28) can be easily computed using logarithm representation in Algorithm 2, which transforms multiplication to a simple addition operation.

| Algorithm 2: Implementation of Gaussian Elimination. | |

| Input: Coefficients of Gaussian map g(i,j), message mi, where 1 < i, j ≤ o, symbol o denotes the number of oil variables, the upper subscript describes the representation transition and the bottom subscript denotes the index. Steps from 1 to 18 describe forward elimination and steps from 19 to 26 describe backward elimination. | |

| Output: Result ri of Gaussian elimination. | |

| 1. | for i = 1 to (o − 1) do |

| 2. | for t = i to o do |

| 3. | |

| 4. | for k = i to o do |

| 5. | |

| 6. | |

| 7. | end for |

| 8. | |

| 9. | |

| 10. | end for |

| 11. | for k = i + 1 to o do |

| 12. | for t = i to o do |

| 13. | |

| 14. | end for |

| 15. | |

| 16. | end for |

| 17. | end for |

| 18. | |

| 19. | count = 1 |

| 20. | for i = o − 2 to 0 do |

| 21. | for j = o − 2 to o − 1 − count do |

| 22. | |

| 23. | end for |

| 24. | |

| 25. | count = count + 1 |

| 26. | end for |

To compute multiplication, values are first converted into their logarithm form by looking up the logarithm table. Then, the relevant values are added, and the sum is returned to a normal representation by looking up the exponential table.

The representation setting is selected in an optimized way when we generate the private coefficients, vinegar values and coefficients of the linear map. The values are randomly generated and are considered to be in logarithm form, because the private coefficients, linear map coefficient and vinegar values are directly multiplied from the first computation. Thus, storing values in logarithm representation is more efficient than leaving them in their normal representation when we consider the next operation. This method has one more advantage. In the logarithm representation, we can express the additional value of “0”, which does not exist in the logarithm look-up table, so it cannot be used in the normal representation. However, the value exists in the exponential table, so we can use this representation for private coefficients.

To find the inverse of a value, we can use an inversion table, which transforms the value using the logarithm table and then subtracts 0xff (255) before returning the resulting value to a normal representation. In our implementation, we use the modified inversion table described in Table A1, which outputs results in logarithm representation with input variables in normal representation. These directly multiply the inverse value in the Gaussian elimination process described in Algorithm 3, in which the first column is inverted and then multiplied with the remaining values in the same row, thus setting the first column to one. After that, each row is bit-wise exclusive-ORed with other rows. This process, called forward elimination, continues to generate triangular form. In the backward elimination, from the last row, the equation is solved by each row.

| Algorithm 3: Multiplication algorithm using logarithm representation written in assembly where ADD, ADC and CLR is addition, addition with carry and clear and Rd and Rr are destination and source registers, (ADD Rd, Rr : Rd←Rd+Rr, ADC Rd, Rr: Rd←Rd+Rr+C, CLR Rd: Rd←Rd ⊕Rd, Rd: destination register, Rr: source register, r1 is cleared.) | |

| Input: Unsigned bytes Al(R2), Bl(R3) | |

| Output: Unsigned byte Al(R2) = Al(R2) + Bl(R3) | |

| 1. | ADD R2, R3 |

| 2. | ADC R2, R1 |

3.2. Assembly Programming

Assembly programming generally exhibits higher performance than high-level programming, such as C and JAVA. This is because we can optimize register allocation and use the status register, which provides a carry bit to determine a certain condition. In our implementation, we adopt assembly programming throughout the whole process to reach to highest performance. Multiplication in logarithm representation can be simplified in addition by using the assembly described in Algorithm 3. First, register r1 is reset. Second, the operands are added. However, if the result is bigger than 0xff, an addition operation on the eight-bit microprocessor generates an output that is subtracted from 256, setting the carry bit. Therefore, this does not give the expected result. However, conducting an addition with the carry bit on the results, we can output the correct result, as we expected.

There is another case that exists. Algorithm 4 describes the exception condition. After central map computations, every parameter is stored into normal representation. The representation cannot map a zero variable into logarithm representation, so we should conduct exception handling for the zero variable. In this case, we directly output zero as a result without computation. In Algorithm 4, Step 1 clears destination register R8. From Steps 2 to 5, input variables (R2 and R3) are compared with zero (R1) to determine the zero variable. From Steps 6 to 13, logarithm mapping is conducted. In Steps 14 and 15, multiplication of R2 and R3 is conducted in logarithm representation. In Steps 16 to 19, mapping to normal representation is conducted.

| Algorithm 4: Exception handling in multiplication for zero variables, where CP, BRCC and MOVW are compare, branch with carry and move register, (CP Rd, Rr: Rd-Rr, BRCC k: if (C=0) then PC ← PC+k+1, MOVW Rd, Rr: Rd+1:Rd ← Rr+1:Rr, ADD Rd, Rr: Rd←Rd+Rr, ADC Rd, Rr: Rd←Rd+Rr+C, CLR Rd: Rd←Rd ⊕Rd, Rd: destination register, Rr: source register, k: label, R1 is cleared, R4, R5 indicate logarithm table, R6, R8 indicate exponential table, R28, R29 indicate Y pointer, ZERO: label name.) | |

| Input: Unsigned bytes An(R2), Bn(R3) | |

| Output: Unsigned byte Cn(R8) = An(R2) × Bn(R3) | |

| 1. | CLR R8 |

| 2. | CP R1, R2 |

| 3. | BRCC ZERO |

| 4. | CP R1, R3 |

| 5. | BRCC ZERO |

| 6. | MOVW R28, R4 |

| 7. | ADD R28, R2 |

| 8. | ADC R29, R1 |

| 9. | LD R2, Y |

| 10. | MOVW R28, R4 |

| 11. | ADD R28, R3 |

| 12. | ADC R29, R1 |

| 13. | LD R3, Y |

| 14. | ADD R2, R3 |

| 15. | ADC R2, R0 |

| 16. | MOVW R28, R6 |

| 17. | ADD R28, R2 |

| 18. | ADC R29, R1 |

| 19. | LD R8, Y |

| 20. | ZERO: |

3.3. Vinegar Monomials

Central map computation is multiplying private coefficients with vinegar variables by the following equation: . These vinegar computations are executed in every central map computation, so vinegar monomials can reduce the vinegar variable computations throughout the whole processes by removing multiplication operations between each vinegar variable. Algorithm 5 describes the pre-computation of vinegar variables, in which we can generate vinegar monomials. The vinegar variables are generated in logarithm form. We left vinegar monomials as a logarithm form, because these variables are directly used for multiplication operations in ∑i∈V,j∈V γijp(i,j), where γ and p are the private coefficient and vinegar monomials, respectively.

| Algorithm 5: Pre-computation of vinegar variables; symbols V and n denote the number of vinegar variables and the total number of vinegar and oil variables, respectively. | |

| Input: Vinegar variables ui. | |

| Output: vinegar monomials p(i,j), 0 < i, j < V. | |

| 1. | for i = 1 to V do |

| 2. | for j = i to V do |

| 3. | p(i,j) = ui × uj |

| 4. | end for |

| 5. | end for |

3.4. On-the-Fly Computation

3.5. Overview of the Computation Process

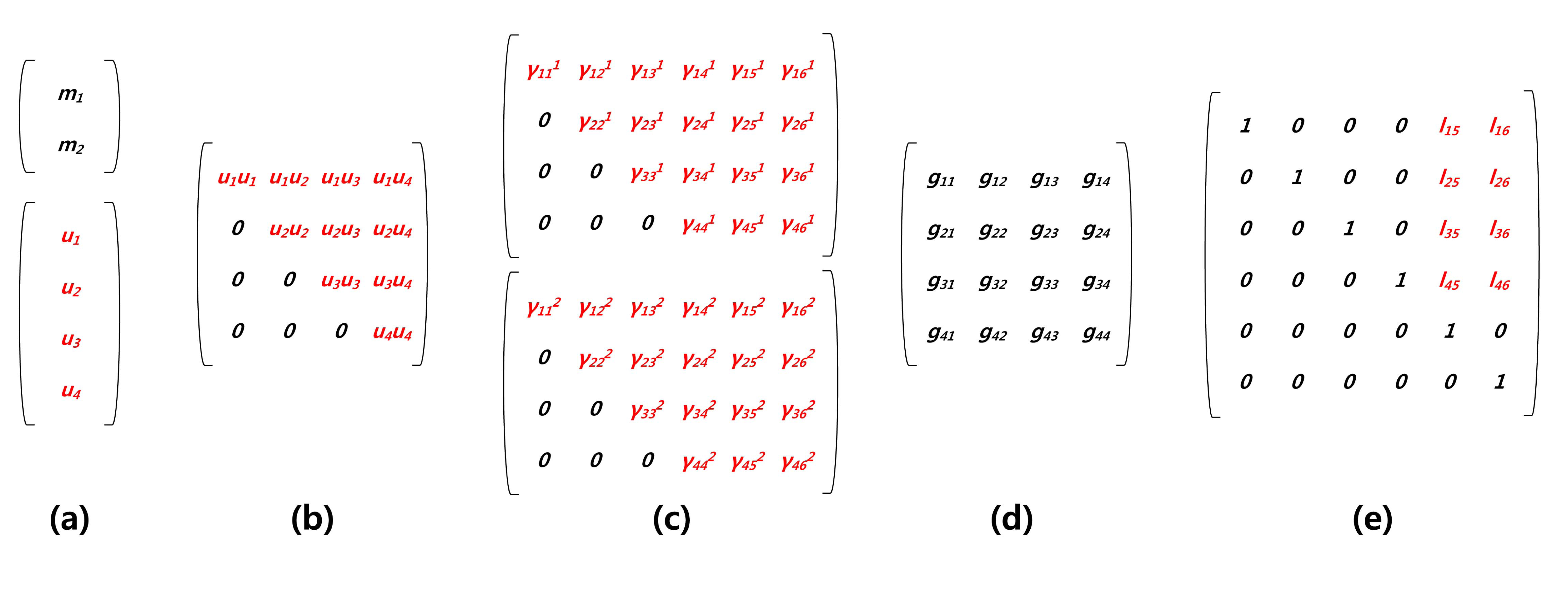

In Figure 3, briefly, we describe the representation of variables for each computation. Firstly, in Figure 3a, a message is hashed and outputted in normal representation. In the case of vinegar variables, logarithm representation is selected. In Figure 3b, ∑i∈V,j∈Vuiuj are the vinegar monomials for efficient computation and are stored in logarithm form. In Figure 3c, we firstly compute ∑i∈V, j∈Vγijp(i,j), where γ and p are private coefficient and vinegar monomials, respectively. After that, we compute the remaining part, ∑i∈V ,j∈OVγiju(i,j), to complete central map computation. In Figure 3d, Gaussian elimination is conducted with the results of the previous step. Finally, in Figure 3e, we generate linear map coefficients in logarithm representation and then compute the linear map computations.

4. Results

In this section, we provide evaluation results on a UOV scheme implementation in terms of memory consumption and computational complexity. Memory consumption is mainly used for key storage. The private key size is for central map and linear map coefficients.

To compute the signature generation, previous implementations stored the private key in memory. However, our implementation stores only the seed values for the random number generator used for secret coefficient generation. For this reason, we can reduce the size of the private key by up to 99.9%. Furthermore, we show a performance enhancement by about 5.78% and 12.19% in signature generation and verification, respectively. This performance is achieved by adopting various optimization techniques that we explored before. The detailed evaluation results are available in Table 3 and 4, respectively.

4.1. Computational Costs

Table 5 shows a detailed analysis of the computation costs for each operation. We separate whole computations into six categories. In central map computation, we divide into vinegar and oil parts. In Gaussian elimination, we divide into forward and backward eliminations. Our method exploits the AES operation for PRNG, so computations that need many private coefficients take many clock cycles. In our implementation, central map computation is the most expensive operation, because the private coefficient size is o(oυ), and it needs 882 AES operations. This result could be reduced more, because we compute two AES operations (32 outputs) in each column for 28 coefficients and did not use four remaining outputs, due to the difficult variable handling. If we fully use 32 outputs, the speed would be improved further.

4.2. Source Code Storage (ROM) Requirements

Table 3 shows the reduction in size of the private key compared with traditional implementations. The size of the seed is computed with the following requirements (security level bit × 3, two for PRNG and one for the hash function). For all parameter variations, our implementation shows a 99.9% reduction in private key size. This is because our method generates private coefficients on the spot, so we store small seed values instead of whole private key values.

4.3. Variable Storage (RAM) Requirements

RAM stores persistent, counting or temporary variables for computation. The minimal RAM requirements are those for storing Gaussian elimination variables, which are generally of o2 complexity. For better performance, we used more RAM to compute the vinegar variables and look-up tables. The computed vinegar variables, which multiply two vinegar variables, are used several times in the central map, so maintaining these values is more beneficial than computing them each time. These have a size of . Second, the logarithm, exponential and inversion tables are used for converting the representations, and each table has a size of 256 bytes. By storing values in RAM, we can access data that is frequently required with lower overheads. The detailed information is available in Table 6.

4.4. Security Analysis

In this paper, we used representative block cipher AES as a core operation of random number generator and hash function to reduce the private key size. Therefore, the security levels highly rely on the strength of the block cipher. Recently, the vulnerability of a symmetric cryptosystem toward a quantum system has been proven by applying Grover’s algorithm to break a symmetric algorithm by brute force, requiring 2n/2 of time, where n is the security bit [21,22]. For this reason, we should select a double-bit size to maintain the same security level of

4.5. Impacts on Other Protocols and Target Devices

We selected ATxmega128a1 as a target device to implement

In the case of this scheme, our method would have huge impacts on other

5. Conclusions

The majority of previous results focused on small public key

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program (no. 10043907, Development of high performance IoT device and Open Platform with Intelligent Software) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIF, Korea).

Appendix

Inversion Table

Table A1 describes the inversion look-up table on GF(28). I = The input is the normal representation, but the output value is the inverse of the input in logarithm representation form.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | a | b | c | d | e | f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | — | 00 | e6 | fe | cd | fd | e5 | 39 | b4 | 38 | e4 | 97 | cc | 11 | 20 | fc |

| 1 | 9b | fb | 1f | f1 | cb | 72 | 7e | 10 | b3 | 8e | f7 | 37 | 07 | 96 | e3 | 3e |

| 2 | 82 | 3d | e2 | 4a | 06 | 46 | d8 | 95 | b2 | 1b | 59 | 8d | 65 | 36 | f6 | 87 |

| 3 | 9a | d0 | 75 | fa | de | f0 | 1e | db | ed | 0f | 7d | ba | ca | 6c | 25 | 71 |

| 4 | 69 | 70 | 24 | 42 | c9 | 2f | 31 | 6b | ec | a3 | 2d | 0e | bf | b9 | 7c | c7 |

| 5 | 99 | 22 | 02 | cf | 40 | f9 | 74 | 9d | 4c | da | 1d | 67 | dd | 77 | 6e | ef |

| 6 | 81 | 91 | b7 | 3c | 5c | 49 | e1 | bd | c5 | 94 | d7 | ab | 05 | 7a | c2 | 45 |

| 7 | d4 | 86 | f5 | ea | 64 | 60 | a1 | 35 | b1 | 2b | 53 | 1a | 0c | 8c | 58 | a8 |

| 8 | 50 | a7 | 57 | af | 0b | 15 | 29 | 8b | b0 | 51 | 16 | 2a | 18 | 19 | 52 | 17 |

| 9 | d3 | 28 | 8a | 85 | 14 | e9 | f4 | 0a | a6 | 34 | a0 | 4f | 63 | 56 | ae | 5f |

| a | 80 | f3 | 09 | 90 | e8 | 3b | b6 | 13 | 27 | bc | e0 | d2 | 5b | 89 | 84 | 48 |

| b | 33 | 44 | c1 | a5 | 04 | 9f | 4e | 79 | c4 | ad | 5e | 93 | 55 | aa | d6 | 62 |

| c | 68 | 4d | 78 | 6f | 9e | 41 | 23 | 03 | 43 | 6a | 30 | 32 | c8 | c0 | a4 | 2e |

| d | ac | c6 | 7b | c3 | be | 5d | 92 | b8 | eb | d5 | 61 | a2 | a9 | 0d | 2c | 54 |

| e | bb | ee | 6d | 26 | dc | df | d1 | 76 | 4b | 83 | 47 | d9 | 88 | 66 | 1c | 5a |

| f | 98 | b5 | 12 | 21 | 3a | ce | 01 | e7 | f2 | 9c | 73 | 7f | 3f | 08 | 8f | f8 |

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koblitz, N. Elliptic curve cryptosystems. Math. Comput. 1987, 48, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, V.S. Use of Ellipticin Curves in Cryptography. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO85 Proceedings; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1986; pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Schmidt, D. Multivariate Public Key Cryptosystems. In Advances in Information Security; Citeseer: Forest Grove, OR, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, L.B.; Aranha, D.F.; Gouvêa, C.P.; Scott, M.; Câmara, D.F.; López, J.; Dahab, R. Tinypbc: Pairings for authenticated identity-based non-interactive key distribution in sensor networks. Comput. Commun. 2011, 34, 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Braeken, A.; Wolf, C.; Preneel, B. A Study of the Security of Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar Signature Schemes. In Topics in Cryptology–CT-RSA 2005; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kipnis, A.; Patarin, J.; Goubin, L. Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar Signature Schemes. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT99; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 206–222. [Google Scholar]

- Petzoldt, A.; Thomae, E.; Bulygin, S.; Wolf, C. Small Public Keys and Fast Verification for Ultivariate Mathcal {Q} Uadratic Public Key Systems. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems–CHES 2011; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, F.; Petzoldt, A.; Portugal, R. Small Private Keys for Systems of Multivariate Quadratic Equations Using Symmetric Cryptography. Avaliable online: http://www.informatik.tu-darmstadt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Group_TK/UOV_cnmac2012-final.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2014).

- Von Maurich, I.; Güneysu, T. Embedded Syndrome-Based Hashing. In Progress in Cryptology-INDOCRYPT 2012; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, T. Random Number Generation Using Aes. Technical Report, Atmel, Availabel online: http://www.atmel.com/ja/jp/Images/article_random_number.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2014).

- Yang, B.-Y.; Cheng, C.-M.; Chen, B.-R.; Chen, J.-M. Implementing Minimized Multivariate Pkc on Low-resource Embedded Systems. In Security in Pervasive Computing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.-Y.; Chen, J.-M.; Chen, Y.-H. Tts: High-speed Signatures on a Low-cost Smart Card. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2004; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 371–385. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth, T.; Kumar, S. A survey of lightweight-cryptography implementations. IEEE Des. Test Comput. 2007, 24, 522–533. [Google Scholar]

- Osvik, D.A.; Bos, J.W.; Stefan, D.; Canright, D. Fast software aes encryption. In Fast Software Encryption; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rukhin, A.; Soto, J.; Nechvatal, J.; Smid, M.; Barker, E. A Statistical Test Suite for Random and Pseudorandom Number Generators for Cryptographic Applications; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Preneel, B.; Govaerts, R.; Vandewalle, J. Hash Functions Based on Block Ciphers: A Synthetic Approach. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO93; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1994; pp. 368–378. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, D. Avrcryptolib.2009. Technical Report, 2009. Availabel online: http://www.daslabor.org/wiki/AVRCryptoLib/en (accessed on 10 January 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Osvik, D.A. Fast embedded software hashing. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2012, 156, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth, T.; Heyse, S.; Von Maurich, I.; Poeppelmann, T.; Rave, J.; Reuber, C.; Wild, A. Evaluation of Sha-3 Candidates for 8-bit Embedded Processors. Proceedings of the Second SHA-3 Candidate Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 23–24 August 2010.

- Czypek, P.; Heyse, S.; Thomae, E. Efficient Implementations of Mqpks on Constrained Devices. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems–CHES 2012; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 374–389. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.H.; Bernstein, E.; Brassard, G.; Vazirani, U. Strengths and weaknesses of quantum computing. SIAM J. Comput. 1997, 26, 1510–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, H.; Gall, F.L. Dihedral hidden subgroup problem: A survey. IPSJ Digital Courier 2005, 1, 470–477. [Google Scholar]

| Statistical Test | Proportion(%) |

|---|---|

| Frequency | 99 |

| Block-Frequency | 99.4 |

| Cumulative-sums | 99.2 |

| Runs | 99.5 |

| Longest-run | 100 |

| Rank | 100 |

| FFT | 100 |

| Serial | 100 |

| Lempel–Ziv | 100 |

| Linear-complexity | 100 |

| Algorithm | Time (cycles/byte) | RAM (bytes) | ROM (bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHA-1 [17] | 579 | 198 | 1,022 |

| SHA-1 [18] | 177 | 122 | 1,352 |

| SHA-256 [17] | 783 | 416 | 1,598 |

| SHA-256 [18] | 335 | 158 | 2,720 |

| Blake-32 [17] | 1,115 | 245 | 6,684 |

| Blake-32 [19] | 324 | 251 | 1,804 |

| Blake-32 [18] | 263 | 206 | 2,076 |

| Skein-256 [18] | 287 | 123 | 2,464 |

| Ours (Davies et al.) | 50 | 48 | 144 |

| Scheme | Private Key (Byte) | Cycles ×103 | Time (ms) 32 MHz | ROM (Byte) | RAM (Byte) | Program Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UOV (21,28) [20] | 21,462 | 1,615 | 50.49 | 2,188 | 441 | C + ASM |

| 0/1 UOV (21,28) [20] | 21,462 | 1,577 | 49.29 | 2,258 | 441 | C + ASM |

| Our UOV (21,28) | 48 | 1,486 | 46.37 | 4,814 | 2,499 | ASM |

| Scheme | Private Key (Byte) | Cycles × 103 | Time (ms) 32 MHz | ROM (Byte) | RAM (Byte) | Program Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UOV (21,28) [20] | 25,725 | 1,690 | 52.83 | 466 | n/a | C + ASM |

| 0/1 UOV (21,28) [20] | 4,851/20,874 | 1,395 | 43.60 | 578 | n/a | C + ASM |

| Our UOV (21,28) | 25,725 | 1,225 | 38.30 | 2,069 | 562 | ASM |

| Operation | Clock Cycle | Proportion (%) | Number of AES Operation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vin-genand pre-com | 9,396 | 0.63 | 2 |

| Central-vinegar | 514,070 | 34.59 | 546 |

| Central-oil | 769,107 | 51.75 | 882 |

| Gaussian-forward | 128,253 | 8.69 | - |

| Gaussian-backward | 1,460 | 0.09 | - |

| Linear | 62,896 | 4.23 | 42 |

| Total | 1,486,182 | 100 | 1,367 |

| Scheme | UOV (21,28) | UOV (28,37) | UOV (44,59) | General |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | 441 | 784 | 1,936 | o2 |

| Our | 1,615 | 2,255 | 4,474 |

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, H.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.; Park, T.; Liu, Z.; Kim, H. Small Private Key MQPKS on an Embedded Microprocessor. Sensors 2014, 14, 5441-5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140305441

Seo H, Kim J, Choi J, Park T, Liu Z, Kim H. Small Private Key MQPKS on an Embedded Microprocessor. Sensors. 2014; 14(3):5441-5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140305441

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Hwajeong, Jihyun Kim, Jongseok Choi, Taehwan Park, Zhe Liu, and Howon Kim. 2014. "Small Private Key MQPKS on an Embedded Microprocessor" Sensors 14, no. 3: 5441-5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140305441

APA StyleSeo, H., Kim, J., Choi, J., Park, T., Liu, Z., & Kim, H. (2014). Small Private Key MQPKS on an Embedded Microprocessor. Sensors, 14(3), 5441-5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/s140305441