1. Introduction

According to the 2020 FAO report, 11% and 14% of worldwide rainfed cropland and pastureland (1.3 × 10

6 ha and 6.6 × 10

6 ha), respectively, are negatively affected by drought [

1], with climate change as the major contributing factor. Drought is a major limitation to the development and production of many crop plants, such as tomato [

2], wheat [

3], and olive [

4]. Plant species exhibit a wide range of drought tolerance and can be classified into five broad categories: sensitive, low, moderate, high, and extreme (xerophytes). Xerophytes are among the most drought-tolerant plants and include halophytic species such as

Atriplex, e.g.,

A. leucoclada [

5] and

A. canescens [

6], which can grow with as little as 100 mm of annual rainfall [

7].

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) have been characterized in several crops [

2,

3,

4] in order to understand their unique and shared strategies for drought mitigation. The activation of stress-responsive genes initiates signaling cascades that lead to biochemical, physiological, and morphological adjustments involved in adaptation [

8,

9]. Transcriptome profiling of key regulatory genes has become an important tool for dissecting plant responses to abiotic stress [

4]. These genes include transcription factors, stress sensors, and protein kinases that regulate pathways involved in osmotic adjustment, antioxidant defense against reactive oxygen species (ROS), hormonal signaling (ABA, JA, and SA), bZIP and AP2/ERF transcription factors, LEA proteins, heat shock proteins, Ca

2+ signaling, membrane stabilization, and C/N ratio regulation [

2,

3,

4,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Mediterranean saltbush (

A. halimus L.) and orache (

A. leucoclada Boiss.) are two important xerophytic fodder plants traditionally used in arid and semi-arid regions due to their high protein content, nutritional value, and ability to thrive under drought and salinity stress [

5,

8,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Both species are perennial C

4 shrubs; however,

A. halimus is widely distributed around the Mediterranean basin and is valued for its higher biomass and protein yield, whereas

A. leucoclada is native to the Fertile Crescent and Arabian Peninsula and is considered more drought adapted, although it remains less widely studied [

5,

15,

18,

19].

Despite their ecological and agricultural importance as stress-tolerant fodder plants, molecular-level studies on drought-response regulation in these species remain scarce. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to conduct a comparative transcriptomic analysis of A. halimus and A. leucoclada under short-term drought stress. This approach is expected to identify novel DEGs and regulatory components that may contribute to drought adaptation. While the primary purpose is to understand drought-responsive genes in Atriplex species, the resulting data are expected to provide novel genetic resources that could inform breeding strategies for improving stress resilience in related cultivated crops.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Growth Conditions, Stress Treatment and Physiological Parameters

Two Atriplex species, Atriplex leucoclada (A.l.) and Atriplex halimus (A.h.), were used in this study, conducted under greenhouse conditions at the Agricultural Research Station in Jubaiha, University of Jordan. The seeds of both species were sown in small pots (100 mL) with “peat moss” under greenhouse conditions, with diurnal temperatures of 25 ± 1 °C (day) and 29 ± 1 °C (night). One-month-old seedlings were transplanted into soil in larger pots (10 L) with 1:1:1 soil:peat moss:sand in the same greenhouse. The soil EC was around 2 dS m−1. Fertilization was added after one week of transplanting (NPK 20:20:20). Seedlings were irrigated every other day with 500 mL tap water (EC around 0.5 dS m−1).

Four-month-old plants were used for the onset of the experiment. Drought stress treatment was applied to stress plants for both species (5 pots, each a replicate) by withholding irrigation for two consecutive weeks, while control plants (another 5 pots, each a replicate) remained under irrigation as previously indicated.

For physiological parameters, relative water content (RWC), leaf dry weight percentage, shoot dry weight percentage and root dry weight percentage were measured for all five replicates for drought and for control plants. RWC was calculated for leaves immersed overnight in distilled water for turgid weight, dried at 65 °C for 3 days, as fresh weight–dry weight/turgid weight–dry weight. Dry weight percentage was calculated as (dry weight/fresh weight) after oven drying at 65 °C for 3 days.

2.2. RNA Isolation and cDNA Preparation

After completion of the drought stress treatment, leaves from the two species were collected from both control and stressed plants. For each treatment and each species, three biological replicates were taken randomly from the five replicates used for the physiological parameters above. Total RNA from leaves was isolated using the RNeasy Plant Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All materials were treated with RNase Away (RNase Away, Molecular Bio Products, San Diego, CA, USA) to avoid the degradation of RNA by RNase. The RNA (5 μg) was used for the subsequent preparation of cDNA for each sample using the SMARTer cDNA Synthesis kit (Clontech, San Jose, CA, USA). The reaction was performed in 0.2 mL nuclease-free PCR tubes (Axgen, Stanford, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The tubes were placed in a thermal cycler (Veriti 96-well; Applied Biosystems, Singapore, Singapore) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.3. RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis of Transcriptome

High-throughput RNA sequencing was essential for obtaining a comprehensive, unbiased profile of transcript abundance in both Atriplex species under drought and control conditions. NGS allows detection of thousands of differentially expressed genes, including novel transcripts and low-abundance regulatory genes, which cannot be reliably captured using targeted methods, such as qPCR or microarrays.

The RNA sequencing was performed at Macrogen (Seoul, Republic of Korea). All samples were bar-coded using dedicated primer adapters (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The amplified and coded libraries were run as paired-end reads with 101 cycles in GAIIx (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The RNA sequencing was analyzed using CLC Genomics Workbench v. 9.1. The RNA-seq analysis was performed in several steps.

First, all

A. halimus reads were de novo assembled (200 cut off for contig lengths). Assembled contigs for the new ESTs were annotated using Blast2Go software [

20]. The annotated file was used as our reference sequence for

Atriplex spp. Second, all reads of RNA sequencing and the reference cDNA, with their annotation, were imported into the program. The 92 bp reads were mapped with the reference

Atriplex spp. cDS with the mapping set, as described; up to three mismatches were allowed. The minimum length of the fraction was 0.9, the minimum similarity fraction was 0.8, and the maximum number of hits for a read was 10.

The expression levels based on the number of mapped reads for the A. leucoclada (A.l.) transcriptome under drought stress and control conditions (A.l. d/c) were compared with each other, as were those of the A. halimus (A.h.) transcriptome under drought stress and control conditions (A.h. d/c). In addition, the expression levels of A.l. and A.h. transcriptomes under the drought condition were also compared (A.l._d/A.h._d). The majority of reads could be mapped uniquely to one location within the Atriplex spp. reference (cDNA) sequence. To normalize for sequencing depth and gene length, reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM) were calculated. DEGs with a p-value ≤ 0.05 were selected. CLC Genomics Workbench (Version 9.5) uses Student’s t-test as a statistical model to calculate the p-values for each DEG for two or more conditions. In addition, the software automatically adjusts the p-values using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR).

2.4. Estimation of Gene Expression Level Using qPCR

Following transcriptome analysis, several DEGs were randomly selected for independent validation. Gene-specific qPCR primers were designed for each selected transcript using Vector NTI 10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primer parameters were set as follows: length 22–28 bp, Tm 58–60 °C, GC content ~60%, amplicon size 150–200 bp, and a CG clamp at the 3′ end (

Supplementary Table S1).

Total RNA from control and drought-treated samples was diluted to a final concentration of 10 ng μL−1 and used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with the GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized in multiple reactions to produce a sufficient template for all qPCR assays.

Quantitative PCR was performed in 96-well plates (Applied Biosystems) using the QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). All reactions were run in triplicate (technical replicates) for each of the three biological replicates. Melting-curve analysis was conducted after each run to verify specificity and to exclude primer dimer formation.

Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method [

21]. For each sample, the Ct of the target gene was normalized to the Ct of the internal reference gene actin (ΔCt = Ct_target − Ct_actin). Actin was selected because it displayed stable Ct values across all treatments (variation < 0.5 cycles). Fold changes were obtained by comparing ΔCt values of drought-treated samples with their corresponding controls (ΔΔCt).

3. Results

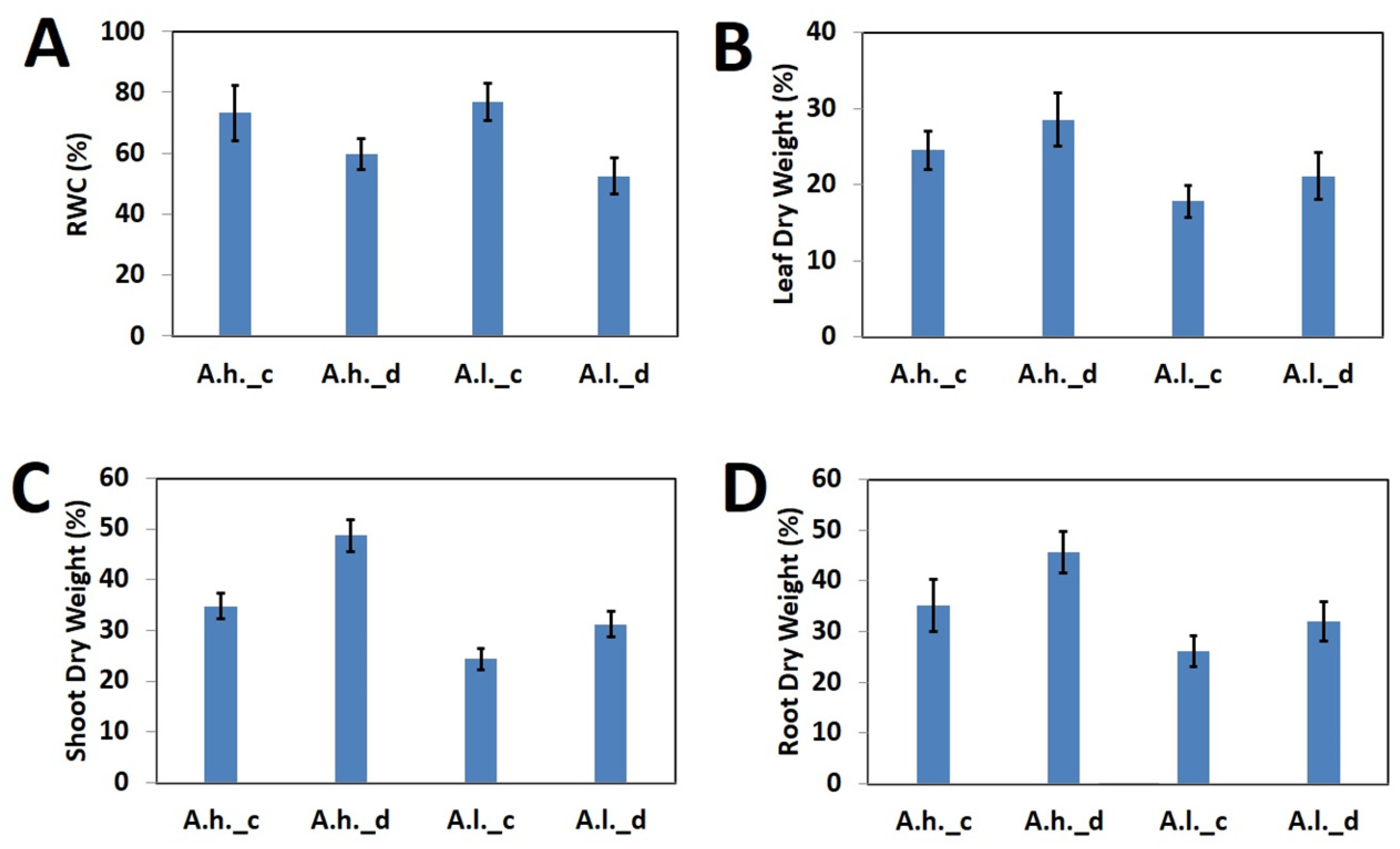

The assessed physiological parameters showed a dramatic effect of drought stress over both species as compared to the control (

Figure 1). RWC dramatically dropped for both

A. halimus and

A. leucoclada after drought stress (

Figure 1A). On the other hand, this was reflected by increased dry weight percentage for leaves (

Figure 1B), shoots (

Figure 1C) and roots (

Figure 1D).

RNA-seq libraries were generated for both A. leucoclada (A.l.) and A. halimus (A.h.) under control (_c) and drought (_d) conditions. Across three biological replicates per treatment, each library produced approximately 60 million reads. Following quality filtering, approximately 5% of reads required trimming to remove low-quality ends, and ambiguous nucleotides represented <1% of all bases, indicating high sequencing quality.

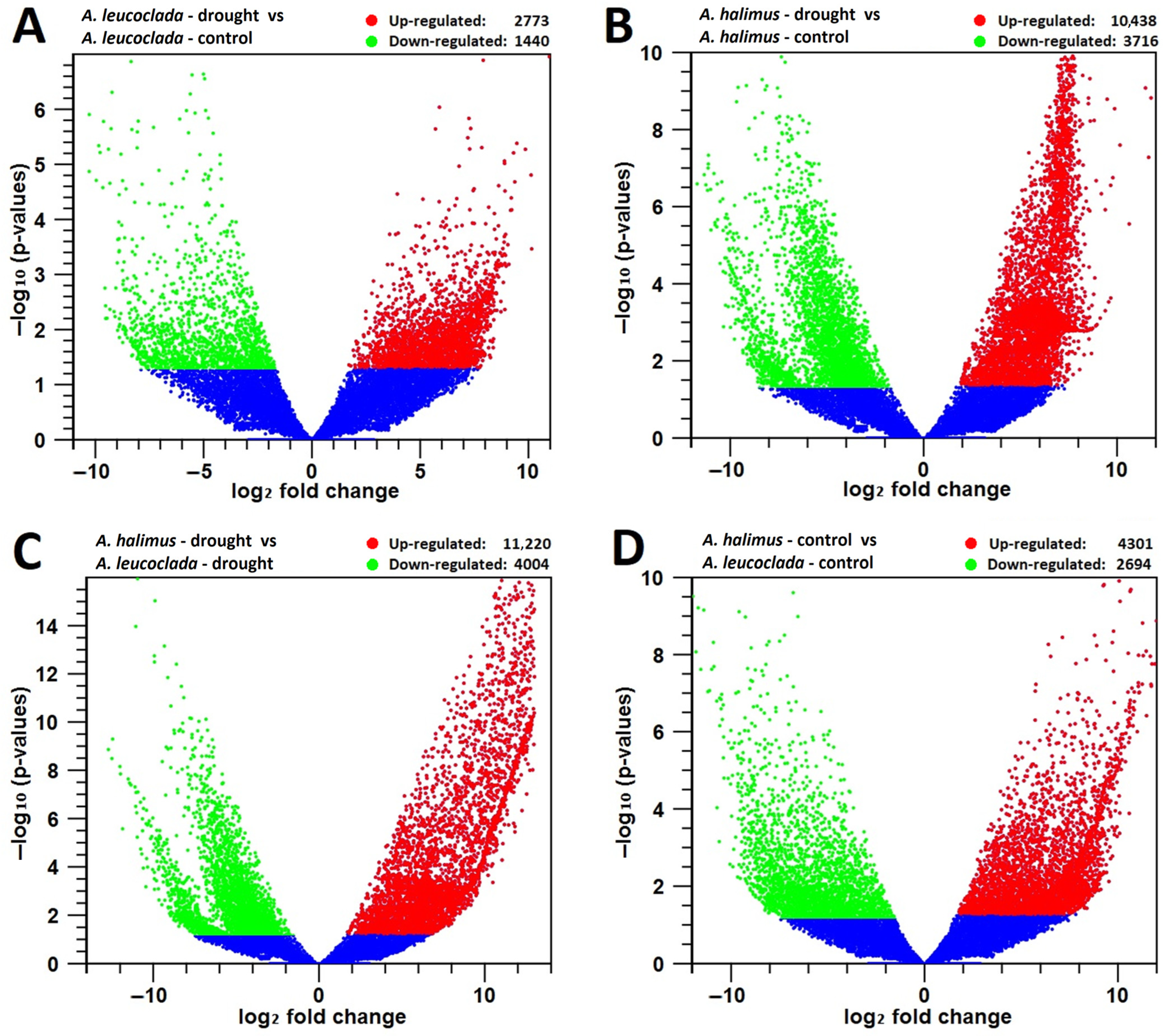

Principal component analysis (PCA) showed tight clustering of biological replicates within each treatment group (

Supplementary Figure S1).Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using a significance threshold of

p ≤ 0.05 (

Figure 2), enabling the characterization of transcriptional responses to drought in both

Atriplex species.

In the case of the

A.l._d vs.

A.l._c pair comparison and with a threshold of Log2FC ≥ 2, a total of 4213 DEGs were identified: 2773 with up-regulated expression and 1440 with down-regulated expression (

Figure 2A). On the other hand, for the

A.h._d vs.

A.h._c pair comparison and with a threshold of Log2FC ≥ 2, a total of 14,154 DEGs were identified; 10,438 with up-regulated expression and 3716 with down-regulated expression (

Figure 2B). However, when comparing the two species under drought stress, for the

A.h._d vs.

A.l._d pair comparison and with a threshold of Log2FC ≥ 2, a total of 15,224 DEGs were identified: 11,220 with up-regulated expression and 4004 with down-regulated expression (

Figure 2C). With similar comparison of the two species under control conditions, for the

A.h._c vs.

A.l._c pair comparison and with a threshold of Log2FC ≥ 2, a total of 6995 DEGs were identified: 4301 with up-regulated expression and 2694 with down-regulated expression (

Figure 2D). qPCR data confirm the RNAseq data, as they showed similar trends in gene expression (

Supplementary Figure S2).

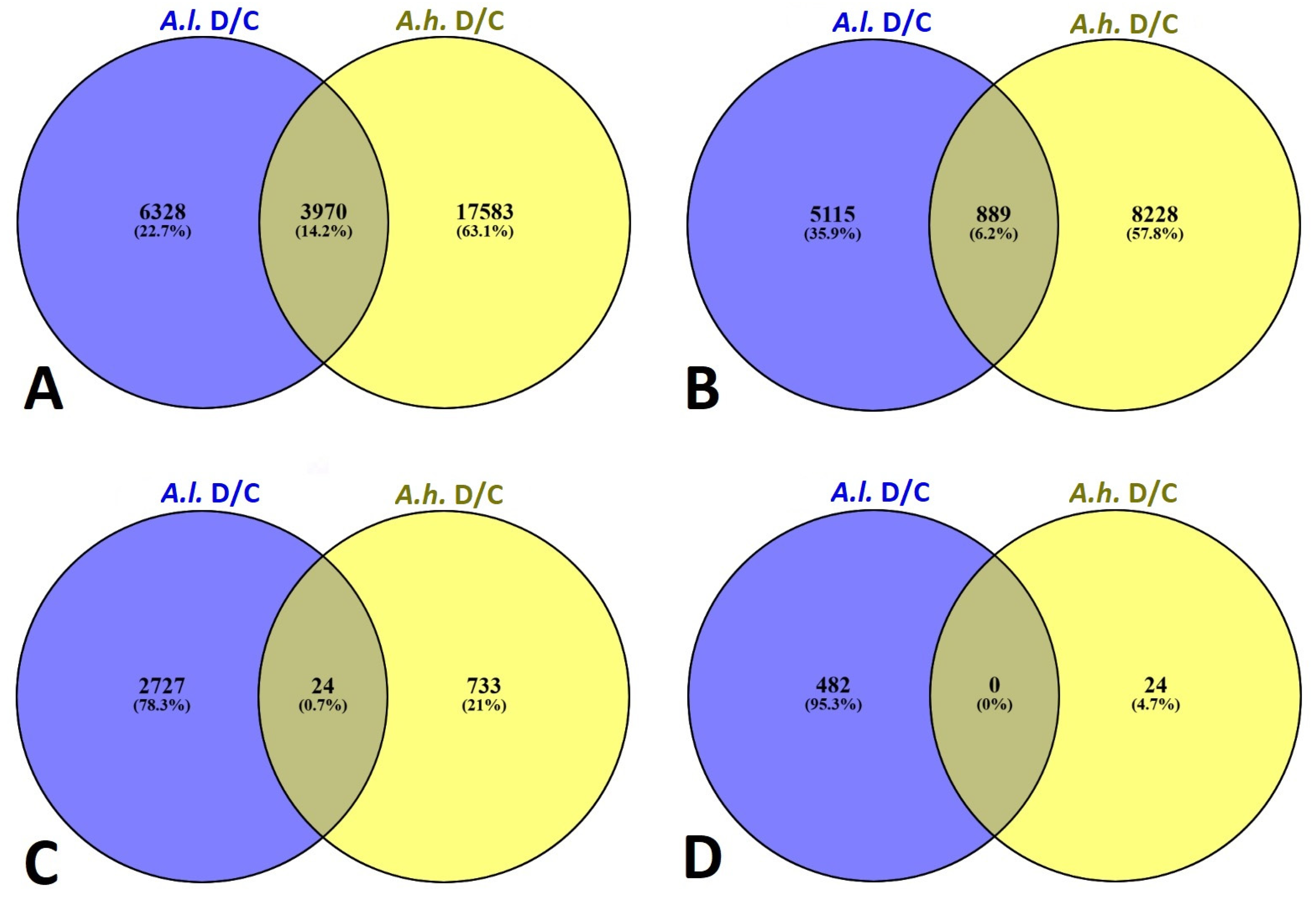

A representative group of Venn diagrams were compiled for major possible combinations of

Atriplex leucoclada (

A.l.) and

Atriplex halimus (

A.h.) under drought stress relative to the control (as baseline) at a cutoff of fold changes ≥ 2, 4, 6 and 8 for up-regulated DEGs (

Figure 3A–D).

A.l. showed an up-regulation of 6328, 5115, 2727 and 482 unique DEGs with fold changes ≥ 2, 4, 6 and 8, respectively. With the same baseline (control), unique DEGs were also evident for

A.h., showing an up-regulation of 17,583, 8228, 733 and 24 unique DEGs with fold changes ≥ 2, 4, 6 and 8, respectively.

Because

A.l. is more tolerant to drought compared with

A.h., the number of drought-responsive genes are much higher in

A.h. to mitigate the drought stress. Nonetheless, major common drought responsive genes were also evident in the overlap section between the two species (

Figure 3A–D), showing 3970, 889, 24 and 0 common DEGs between the two species under drought stress with fold changes ≥ 2, 4, 6 and 8, respectively.

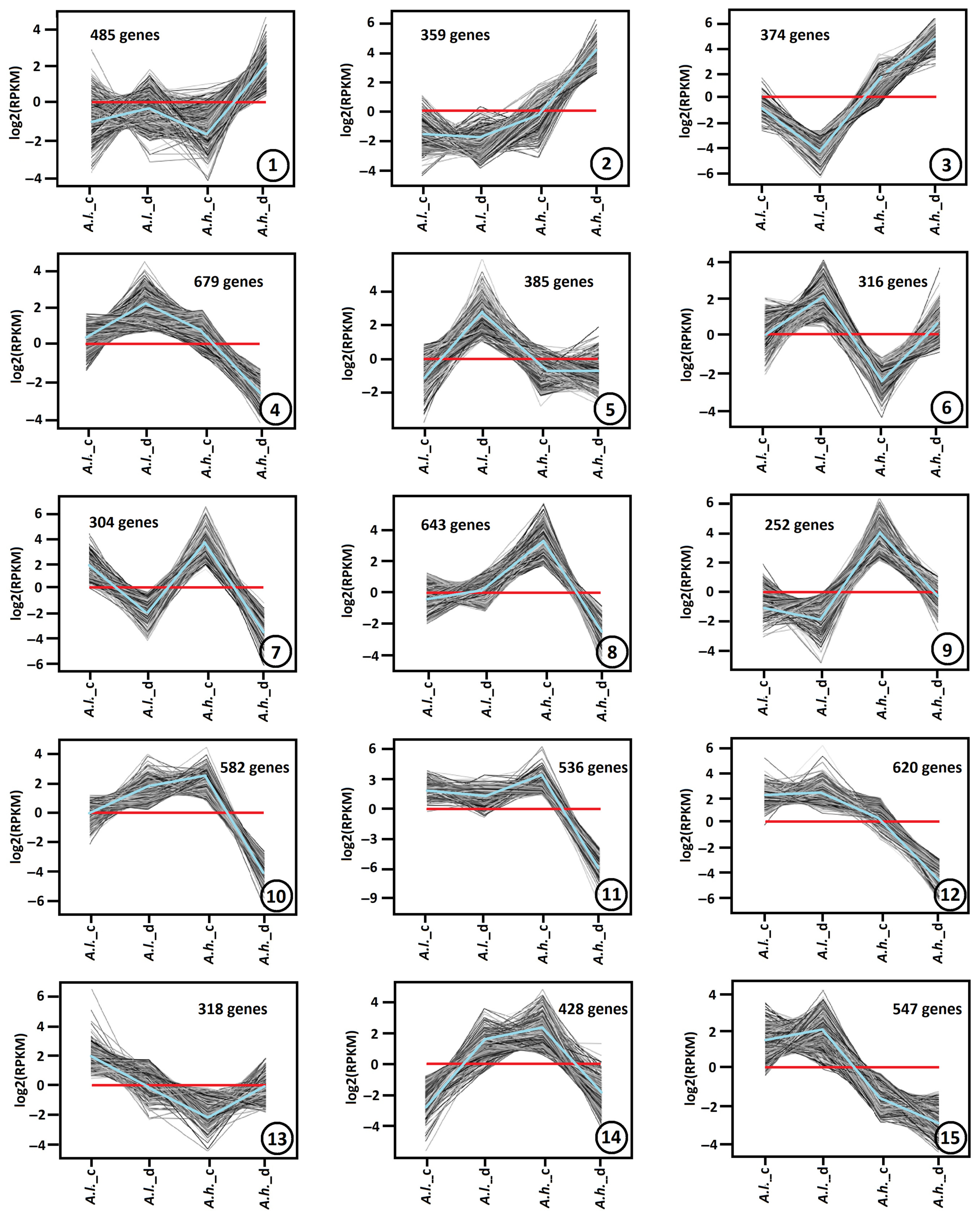

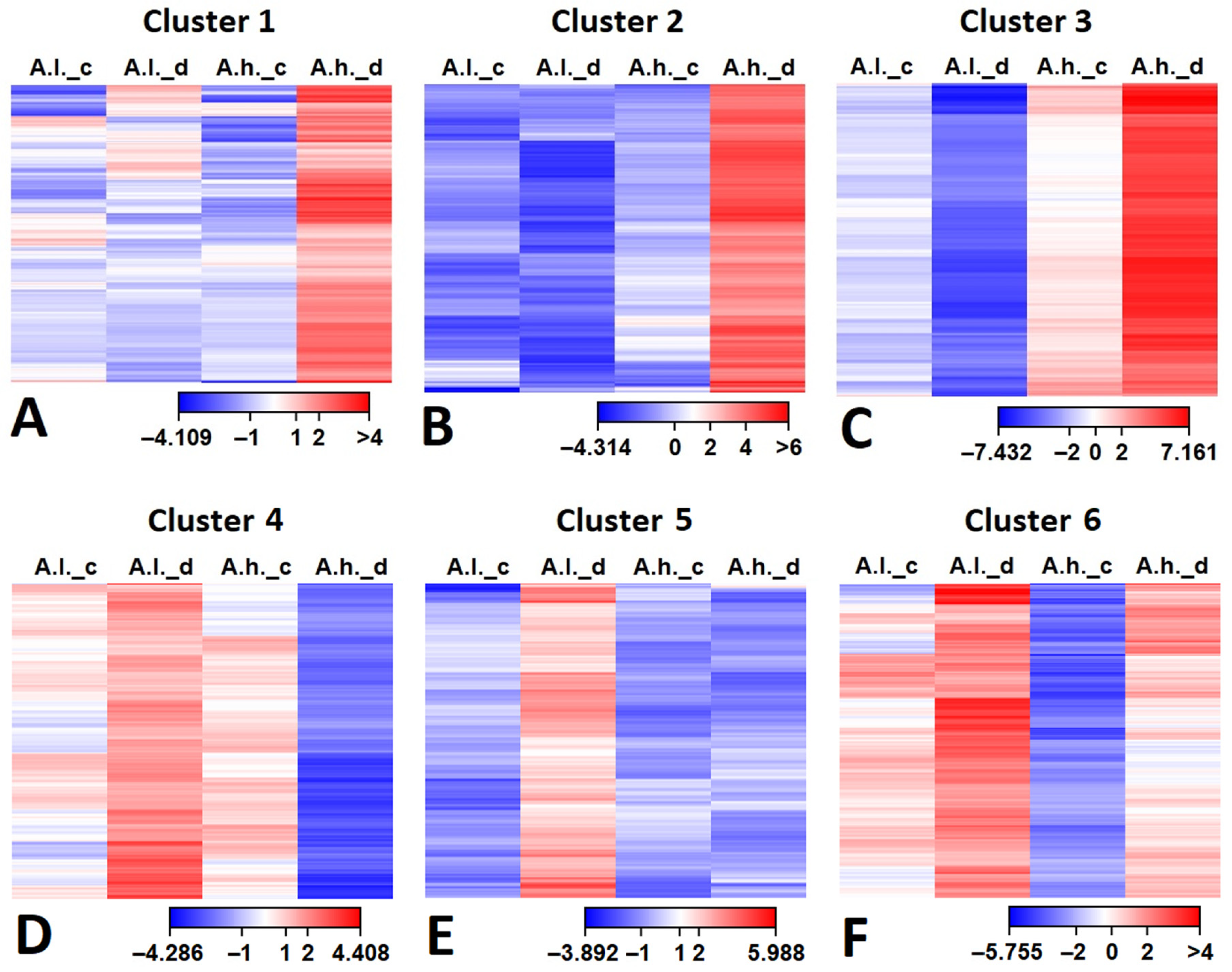

Several thousand DEGs during drought stress showed significant up-regulation or down-regulation (

p-value < 0.01, fold change > 2 or <0.5). On the basis of similar kinetic patterns of expression, all DEGs were classified into unique gene expression patterns (clusters) (

Figure 4). In our dataset, the optimal number of distinct expression profiles produced by the algorithm was 15. Even if some patterns appear visually close (such as clusters 11 and 12), their underlying expression values differ sufficiently for the algorithm to classify them as unique groups.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of Atriplex leucoclada (A.l.) and Atriplex halimus (A.h.) species under both control (_c) and drought stress (_d) conditions were used to reveal these 15 clusters. Each cluster was built from a large number of DEGs, ranging from 252 up to 679 genes.

The gene expression patterns of cluster 1 (485 DEGs), cluster 2 (359 DEGs) and cluster 3 (374 DEGs) exhibit similar changes, where DEGs are up-regulated mainly in

A.h. (under drought stress). The major difference between them is the fold change, which is minimal in cluster 1, moderate in cluster 2 and prominent in cluster 3 (

Figure 3). In addition, it was deeply down-regulated in

A.l. (under drought stress) in cluster 3. On the contrary, cluster 4 (679 DEGs), cluster 5 (385 DEGs) and cluster 6 (316 DEGs) show the opposite pattern for

A.l., where DEGs are up-regulated in

A.l. compared to

A.h. (under drought stress). However, the major difference between them is the expression level in

A.h. (under drought stress), which is down-regulated in cluster 4, flat in cluster 5 and slightly up-regulated in cluster 6.

All DEGs in the first six clusters (

Figure 5) were retrieved from the RNA-seq data along with their annotation. Their expression (FRKM calibration) were subjected to hierarchal clustering for

Atriplex leucoclada (

A.l.) and

Atriplex halimus (

A.h.) under both control (_c) and drought (_d) conditions, and their expression levels are presented as a heat map (

Figure 5A–F). It was clear from the heat maps for clusters 1, 2 and 3 (

Figure 5A–C) that most DEGs were more up-regulated in

A.h. (under drought stress), indicating unique gene expression mainly under drought stress in

A. halimus in comparison to its control counterpart and to

A. leucoclada.

Extensive tables covering major gene families were compiled (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6). They contain essential information generated from the RNA-seq analysis, including differential expression results, annotations, and pathway details. These datasets are crucial for transparency and reproducibility in transcriptomics research.

When comparing DEGs between the three clusters (1, 2 and 3) in

Atriplex halimus (

A.h.) (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3), four common gene families were prominent: transcriptional regulation, protective proteins and enzymes, metabolism and osmotic adjustment, and finally hormone signaling. While transporters were common between clusters 1 and 2 (

Table 1 and

Table 2), stress perception and signaling were common between clusters 1 and 3 (

Table 1 and

Table 3), while photosynthesis and energy balance were common between clusters 2 and 3 (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Major DEGs with high expression in cluster 1 included F-box protein (2.83 fold) and WRKY TF (3.47 fold) (

Table 1). In cluster 2, highly expressed genes included zinc knuckle family protein (3.89 fold) and cation calcium exchanger 4 (CAX4) (4.59 fold) (

Table 2). In cluster 3, top up-regulated genes were recorded for calcineurin-like phosphoesterase-like protein (5.85 fold) and ARM repeat protein interacting with ABF2 (ARIA) (6.21) (

Table 3).

On the other hand, when comparing DEGs between the three clusters (4, 5 and 6) in

Atriplex leucoclada (

A.l.) (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6), six common gene families were prominent: stress perception and signaling, transcriptional regulation, protective proteins and enzymes, metabolism and osmotic adjustment and finally transporters and hormone signaling, while cell wall structural proteins were common between clusters 4 and 5 (

Table 4 and

Table 5). Major DEGs with high expression in cluster 4 included casein kinase I (4.41 fold) and JAZ-like protein (2.49 fold) (

Table 4). In cluster 5, highly expressed genes included Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK) (3.55 fold) and Sodium bile acid cotransporter 7-like (BASS, SLC10-like) (2.26 fold) (

Table 5). In cluster 6, top up-regulated genes were recorded for calmodulin-binding (4.12 fold) and protein Clp1 homolog (chaperone) (4.07 fold) (

Table 6).