Illegal Wildlife Trade in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia: Species, Prices, and Conservation Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Document the taxonomic diversity, trade volume, and market value of species traded across market, pet shop, farm, and online contexts;

- (2)

- Assess the conservation status of traded species using the IUCN Red List and CITES listings;

- (3)

- Analyze temporal trends in prices and individual numbers.

2. Materials and Methods

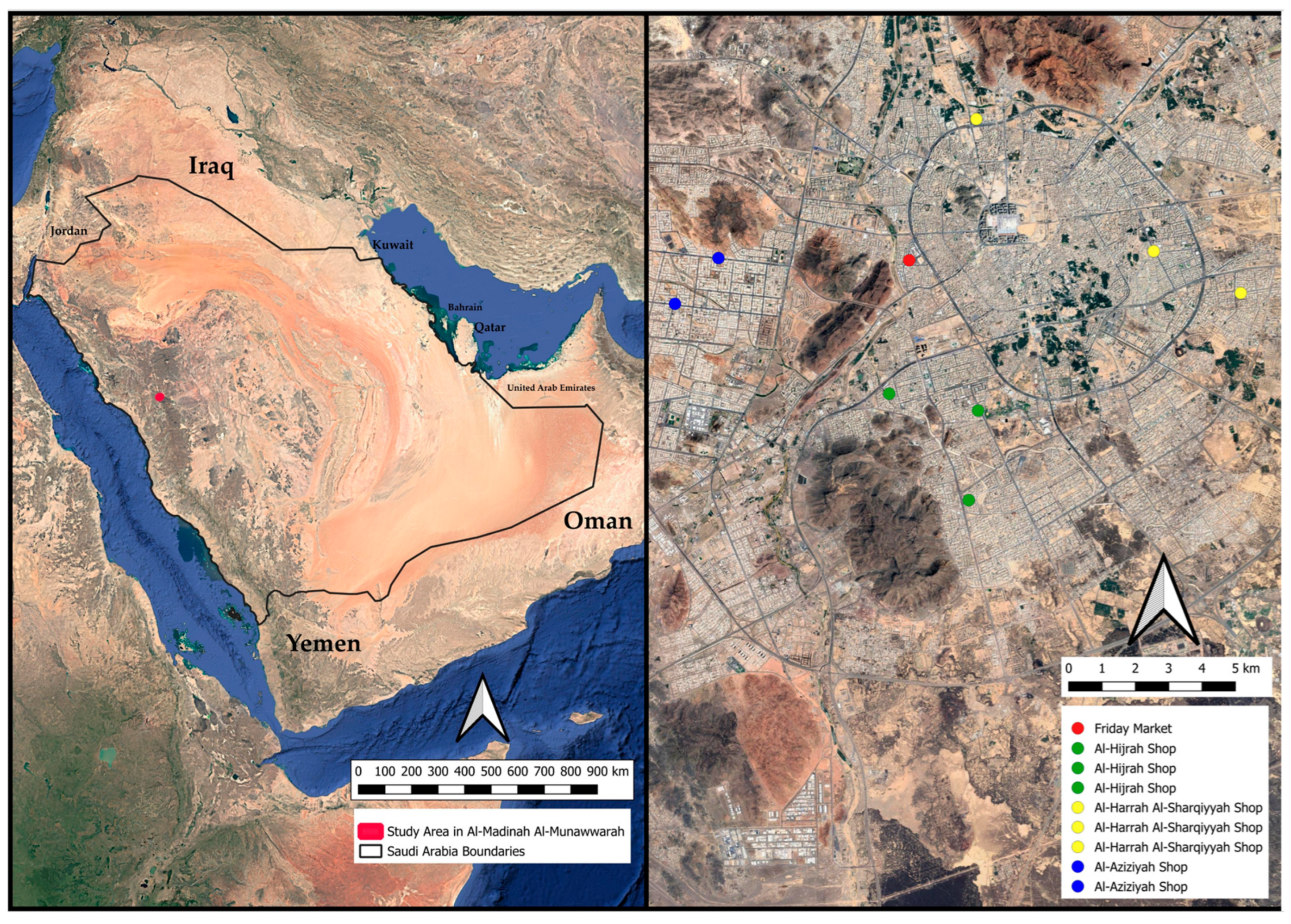

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Friday Market Surveys

2.2.2. Pet Shop Monitoring

2.2.3. Farm Investigations

2.2.4. Online Platform Monitoring

2.2.5. Data Recording and Quality Control

2.3. Statistical Analyses

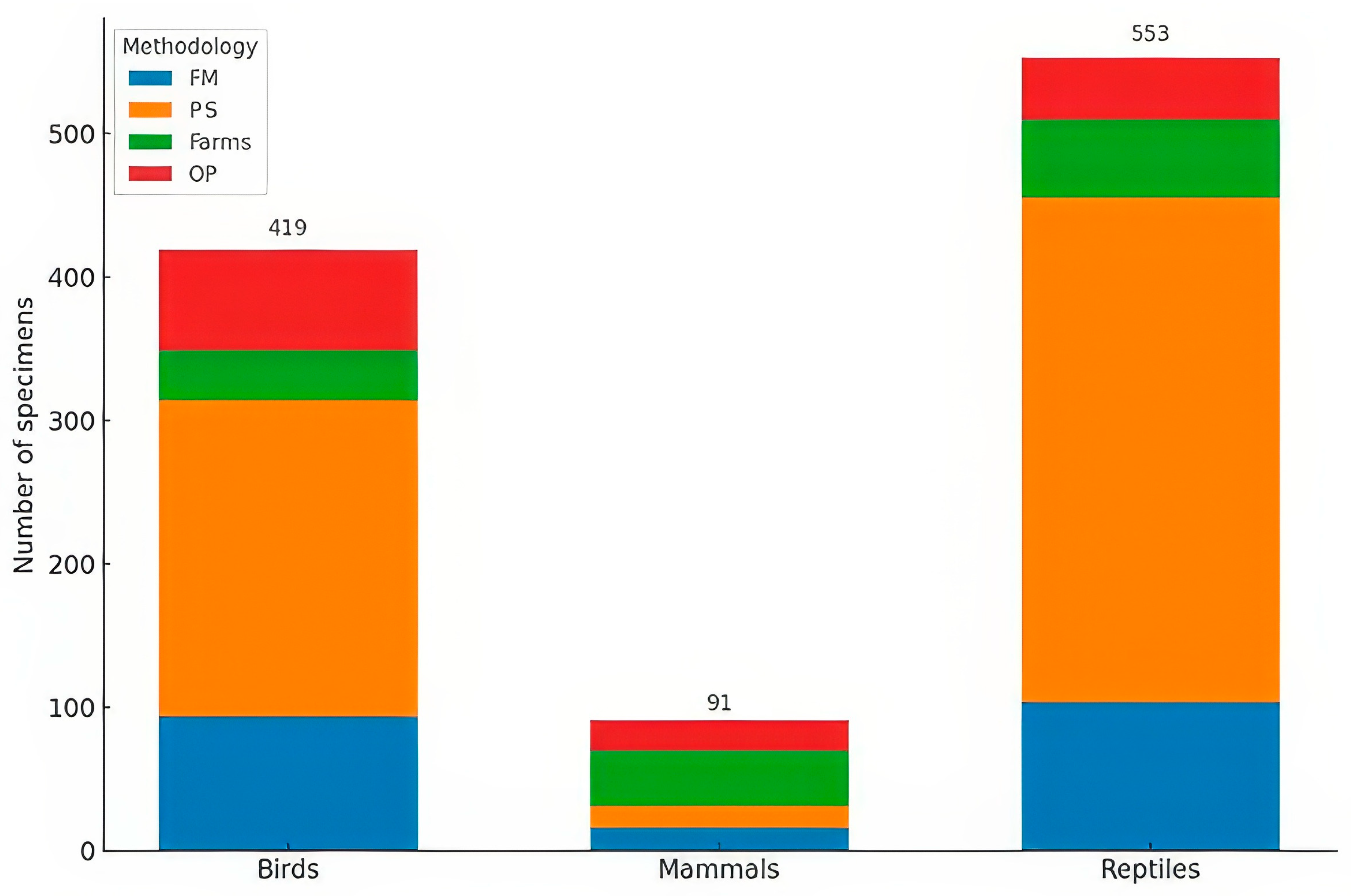

3. Results

3.1. Bird Trade

3.2. Mammal Trade

3.3. Reptile Trade

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. Pet Shops and Friday Market in the Regional Context

4.3. Online Platforms and Displacement

4.4. Implications for Monitoring and Policy

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosen, G.E.; Smith, K.F. Summarizing the evidence on the international trade in illegal wildlife. EcoHealth 2010, 7, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffers, B.R.; Oliveira, B.F.; Lamb, I.; Edwards, D.P. Global wildlife trade across the tree of life. Science 2019, 366, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. Security and Conservation: The Politics of the Illegal Wildlife Trade; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ‘t Sas-Rolfes, M.; Challender, D.W.; Hinsley, A.; Veríssimo, D.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Illegal wildlife trade: Scale, processes, and governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman, V. An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.A.; Tilley, H.B.; Lau, W.; Dudgeon, D.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Dingle, C. CITES and beyond: Illuminating 20 years of global, legal wildlife trade. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, N.; Wintle, B.C.; ’t Sas-Rolfes, M.; Athanas, A.; Beale, C.M.; Bending, Z.; Dai, R.; Fabinyi, M.; Gluszek, S.; Haenlein, C.; et al. Emerging illegal wildlife trade issues in 2020: A global horizon scan. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Vidal, P.; Carrete, M.; Hiraldo, F.; Blanco, G.; Tella, J.L. Discrepancies between national legislation and illegal domestic wildlife trade: The case of Neotropical parrots. Animals 2022, 12, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, E.; Al Hasani, I.; Al Share, T.; Abed, O.; Amr, Z. Animal trade in Amman local market, Jordan. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 4, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Aloufi, A.; Eid, E. Conservation perspectives of illegal animal trade at markets in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Traffic Bull. 2014, 26, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Aloufi, A.; Eid, E. Zootherapy: A study from the northwestern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Said, M.R.; Makhlouf, H.; Amr, Z.S.; Eid, E. Illegal trade in wildlife species in Beirut, Lebanon. Vertebr. Zool. 2018, 68, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, E.; Handal, R. Illegal hunting in Jordan: Using social media to assess impacts on wildlife. Oryx 2018, 52, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handal, E.N.; Amr, Z.S.; Basha, W.S.; Qumsiyeh, M.B. Illegal trade in wildlife vertebrate species in the West Bank, Palestine. J. Asia-Pacific Biodivers. 2021, 14, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman, V.; Bergin, D.; Morcatty, T.Q. Illegal wildlife trade: Surveying open animal markets and online platforms to understand the poaching of wild cats. Biodiversity 2019, 20, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badelu, N.; Sardari, P.; Mohammadi, A.; Mohammadalizadegan, A.; Noorbakhsh, A. Investigating the Illegal Online Trade of Spur-thighed Tortoises on an Iranian Marketplace Website: A Preliminary Survey. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 20, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadinia, M.S.; Maheshwari, A.; Nawaz, M.A.; Ambarlı, H.; Gritsina, M.A.; Koshkin, M.A.; Rosen, T.; Hinsley, A.; Macdonald, D.W. Belt and Road Initiative may create new supplies for illegal wildlife trade in large carnivores. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1267–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardari, P.; Felfelian, F.; Mohammadi, A.; Nayeri, D.; Davis, E.O. Evidence on the role of social media in the illegal trade of Iranian wildlife. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, I.; Balzani, P.; Carneiro, L.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Macêdo, R.; Tarkan, A.S.; Ahmed, D.A.; Bang, A.; Bacela-Spychalska, K.; Bailey, S.A.; et al. Taming the terminological tempest in invasion science. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1357–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Pasqualato, A.; Wingard, J.; Gordine, S. To and Through the Gulf: IWT Routes & Legal Environment—Rapid Review; Legal Atlas, LLC: Missoula, MT, USA, 2022; Available online: https://cheetah.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/gulf_iwt_routes_ver_3_feb_8.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Vu, A.N. Demand reduction campaigns for the illegal wildlife trade in authoritarian Vietnam: Ungrounded environmentalism. World Dev. 2023, 164, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Patoka, J.; Magalhães, A.L.B.; Kouba, A.; Faulkes, Z.; Jerikho, R.; Vitule, J.R.S. Invasive aquatic pets: Failed policies increase risks of harmful invasions. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 3037–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natali, M. Halting the Illegal Trade of Cheetahs as Exotic Pets. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2024, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricorache, P.; Nowell, K.; Wirth, G.; Mitchell, N.; Boast, L.K.; Marker, L. Pets and pelts: Understanding and combating poaching and trafficking in cheetahs. In Cheetahs: Biology and Conservation: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes; Marker, L., Boast, L., Schmidt-Küntzel, A., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2018; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Abaunza, C.M. Human trafficking in the MENA region: Trends and perspectives. In The Evolution of Illicit Flows: Displacement and Convergence among Transnational Crime; Reitano, T., Shaw, M., Hunter, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pence, V.C.; Ballesteros, D.; Walters, C.; Reed, B.M.; Philpott, M.; Dixon, K.W.; Pritchard, H.W.; Culley, T.M.; Vanhove, A.-C. Forty-four years of global trade in CITES-listed snakes: Trends, biological and conservation implications. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 250, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auliya, M.; Altherr, S.; Ariano-Sánchez, D.; Baard, E.H.W.; Brown, C.; Brown, R.M.; Cantu, J.-C.; Gentile, G.; Gildenhuys, P.; Henningheim, E.; et al. Trade in live reptiles, its impact on wild populations, and the role of the European market. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 204, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchamp, F.; Angulo, E.; Rivalan, P.; Hall, R.J.; Signoret, L.; Bull, L.; Meinard, Y. Rarity value and species extinction: The anthropogenic Allee effect. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshamlih, M.; Alzayer, M.; Hajwal, F.; Khalili, M.; Khoury, F. Introduced birds of Saudi Arabia: Status and potential impacts. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, J.L.; Hiraldo, F. Illegal and legal parrot trade shows a long-term, cross-cultural preference for the most attractive species increasing their risk of extinction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scientific Name | Status | Methodology Used | # of Specimens | Avg. Price Per Individual (USD) | Total Prices | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CITES | Red List | CMS | FM | PM | Farms | OP | ||||

| Family: Accipitridae | ||||||||||

| Aquila chrysaetos | II | LC | II | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 270 | 270 |

| Buteo jamaicensis | II | LC | II | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | 270 | 540 |

| Buteo rufinus | II | LC | II | - | 2 | - | 1 | 3 | 41 | 123 |

| Family: Cacatuidae | ||||||||||

| Nymphicus hollandicus | NL | LC | NL | - | 15 | - | 4 | 19 | 95 | 1805 |

| Cacatua galerita | II | LC | NL | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1350 | 1350 |

| Family: Columbidae | ||||||||||

| Geopelia cuneata | NL | LC | NL | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 54 | 108 |

| Streptopelia decaocto | NL | LC | NL | 3 | 9 | - | - | 12 | 3 | 36 |

| Streptopelia roseogrisea | NL | LC | NL | 5 | 4 | 5 | - | 14 | 14 | 196 |

| Metriopelia melanoptera | NL | LC | NL | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 20 | 40 |

| Family: Estrildidae | ||||||||||

| Erythrura gouldiae | NL | LC | NL | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 35 | 35 |

| Family: Falconidae | ||||||||||

| Falco tinnunculus | II | LC | II | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 6 | 25 | 148 |

| Family: Gruidae | ||||||||||

| Anthropoides virgo | II | LC | II | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 405 | 810 |

| Family: Hypocoliidae | ||||||||||

| Hypocolius ampelinus | NL | LC | NL | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 16 | 32 |

| Family: Numididae | ||||||||||

| Numida meleagris | NL | LC | NL | 1 | - | 2 | - | 3 | 14 | 42 |

| Family: Phasianidae | ||||||||||

| Alectoris chukar | NL | LC | NL | - | - | - | 14 | 14 | 135 | 1890 |

| Ammoperdix heyi | NL | LC | NL | 2 | 5 | - | 4 | 11 | 51 | 559 |

| Pavo cristatus | III | LC | NL | - | - | 13 | 3 | 16 | 995 | 15,120 |

| Phasianus colchicus | NL | LC | NL | 1 | - | 5 | - | 6 | 35 | 210 |

| Family: Psittacidae | ||||||||||

| Ara chloropterus | II | LC | NL | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2025 | 2025 |

| Psittacus erithacus | I | EN | NL | 20 | 20 | - | 13 | 53 | 805 | 42,665 |

| Amazona aestiva | II | NT | NL | - | 7 | - | 6 | 13 | 1370 | 17,820 |

| Pseudeos fuscata | II | LC | NL | - | 4 | - | - | 4 | 675 | 2700 |

| Pyrrhura molinae | II | LC | NL | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 135 | 135 |

| Eolophus roseicapilla | II | LC | NL | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 486 | 486 |

| Ara ararauna | II | LC | NL | 2 | 6 | - | 4 | 12 | 1800 | 21,600 |

| Agapornis fischeri | II | NT | NL | - | 2 | - | 4 | 6 | 54 | 324 |

| Pionus menstruus | II | LC | NL | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 189 | 378 |

| Family: Psittaculidae | ||||||||||

| Trichoglossus haematodus subsp. Moluccanus | NA | LC | NL | - | 3 | - | 1 | 4 | 675 | 2700 |

| Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae | I | LC | NL | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 203 | 406 |

| Psittacula krameri | NL | LC | NL | 4 | 7 | - | 9 | 20 | 228 | 4553 |

| Psittacula derbiana | II | LC | NL | - | 6 | - | - | 6 | 320 | 1918 |

| Eos bornea | II | LC | NL | - | 18 | - | - | 18 | 391 | 8235 |

| Family: Pycnonotidae | ||||||||||

| Pycnonotus xanthopygos | NL | LC | NL | 4 | 5 | - | - | 9 | 12 | 112 |

| Pycnonotus leucotis | NL | LC | NL | 33 | 71 | - | - | 104 | 15 | 1604 |

| Family: Strigidae | ||||||||||

| Bubo ascalaphus | NL | LC | NL | 1 | 135 | 135 | ||||

| Asio otus | II | LC | NL | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 351 | 351 |

| Family: Struthionidae | ||||||||||

| Struthio camelus | I | LC | NL | - | - | 8 | - | 8 | 878 | 7020 |

| Family: Sturnidae | ||||||||||

| Gracula religiosa | II | LC | NL | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | 459 | 918 |

| Acridotheres tristis | NL | LC | NL | 12 | 22 | - | - | 34 | 28 | 942 |

| Scientific Name | Status | Methodology Used | # of Specimens | Avg. Price Per Individual (USD) | Total Prices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CITES | Red List | FM | PM | Farms | OP | ||||

| Family: Bovidae | |||||||||

| Gazella leptoceros | I | EN | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 810 | 810 |

| Oryx beisa | NL | EN | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 21,600 | 21,600 |

| Gazella gazella | NL | EN | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 810 | 1620 |

| Tragelaphus derbianus | NL | VU | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 13,500 | 27,000 |

| Antilope cervicapra | III | LC | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 1755 | 3510 |

| Family: Canidae | |||||||||

| Canis aureus | III | LC | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 594 | 1188 |

| Canis lupus | III | LC | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | 540 | 1080 |

| Family: Cercopithecidae | |||||||||

| Colobus vellerosus | II | CR | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 10,800 | 10,800 |

| Papio hamadryas | II | LC | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 362 | 3621 |

| Family: Erinaceidae | |||||||||

| Paraechinus aethiopicus | NL | LC | 1 | 3 | - | 1 | 5 | 20 | 98 |

| Family: Felidae | |||||||||

| Acinonyx jubatus | II | VU | - | - | 9 | 2 | 11 | 71,280 | 784,080 |

| Panthera leo | I | VU | - | - | 7 | 2 | 11 | 13,377 | 147,147 |

| Caracal caracal | I | LC | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 405 | 405 |

| Family: Herpestidae | |||||||||

| Suricata suricatta | NL | LC | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1215 | 1215 |

| Family: Perissodactyla | |||||||||

| Equus quagga | NL | NT | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 2025 | 4050 |

| Family: Petauridae | |||||||||

| Petaurus breviceps | NL | LC | 1 | 5 | - | 2 | 8 | 135 | 1080 |

| Family: Procaviidae | |||||||||

| Procavia capensis | NL | LC | 6 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 25 | 123 | 3075 |

| Family: Sciuridae | |||||||||

| Eutamias sibiricus | NL | LC | 2 | 2 | - | - | 4 | 108 | 432 |

| Sciurus anomalus | NL | LC | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 540 | 540 |

| Callosciurus finlaysonii | NL | LC | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 540 | 540 |

| Scientific Name | Status | Methodology Used | # of Specimens | Avg. Price Per Individual (USD) | Total Prices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CITES | Red List | FM | PM | Farms | OP | ||||

| Family: Testudinidae | |||||||||

| Centrochelys sulcata | II | EN | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | 473 | 946 |

| Family: Chamaeleonidae | |||||||||

| Chamaeleo calyptratus | II | LC | 4 | 14 | - | 2 | 20 | 24 | 480 |

| Chamaeleo chamaeleon | II | LC | 10 | 32 | - | 3 | 45 | 14 | 630 |

| Family: Crocodylidae | |||||||||

| Crocodylus niloticus | II | LC | 1 | 7 | - | 1 | 9 | 226 | 2030 |

| Family: Boidae | |||||||||

| Eryx jaculus | II | LC | 3 | 3 | - | - | 6 | 19 | 114 |

| Boa constrictor | II | LC | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 4 | 676 | 2705 |

| Family: Colubridae | |||||||||

| Hemorrhois nummifer | NL | LC | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | 14 | 28 |

| Platyceps saharicus | NL | LC | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 14 | 14 |

| Spalerosophis diadema | NL | LC | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 4 | 14 | 56 |

| Family: Iguanidae | |||||||||

| Iguana iguana | II | LC | 3 | 7 | - | 2 | 12 | 174 | 2096 |

| Family: Psammophidae | |||||||||

| Malpolon monspessulanus | NL | LC | 2 | - | 3 | 3 | 8 | 27 | 216 |

| Psammophis schokari | NL | LC | 7 | 13 | 7 | 4 | 31 | 41 | 1256 |

| Family: Geoemydidae | |||||||||

| Mauremys rivulata | NL | LC | - | 39 | - | - | 39 | 17 | 686 |

| Family: Pythonidae | |||||||||

| Python bivittatus | II | VU | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2160 | 4320 |

| Python sebae | II | NT | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 3 | 540 | 1620 |

| Family: Testudinidae | |||||||||

| Testudo graeca | II | VU | 11 | 22 | - | - | 33 | 54 | 1769 |

| Family: Emydidae | |||||||||

| Trachemys scripta | NL | LC | - | 156 | - | - | 156 | 14 | 2184 |

| Family: Agamidae | |||||||||

| Uromastyx aegyptia | II | VU | 55 | 53 | 43 | 23 | 174 | 108 | 18,792 |

| Uromastyx ornata | II | LC | 1 | 22 | 22 | ||||

| Family: Varanidae | |||||||||

| Varanus griseus | I | LC | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 68 | 68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aloufi, A.; Eid, E.; Alamri, M. Illegal Wildlife Trade in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia: Species, Prices, and Conservation Risks. Diversity 2025, 17, 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17090615

Aloufi A, Eid E, Alamri M. Illegal Wildlife Trade in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia: Species, Prices, and Conservation Risks. Diversity. 2025; 17(9):615. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17090615

Chicago/Turabian StyleAloufi, Abdulhadi, Ehab Eid, and Mohamed Alamri. 2025. "Illegal Wildlife Trade in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia: Species, Prices, and Conservation Risks" Diversity 17, no. 9: 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17090615

APA StyleAloufi, A., Eid, E., & Alamri, M. (2025). Illegal Wildlife Trade in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia: Species, Prices, and Conservation Risks. Diversity, 17(9), 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17090615