African Small Mammals (Macroscelidea and Rodentia) Housed at the National Museum of Natural History and Science (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

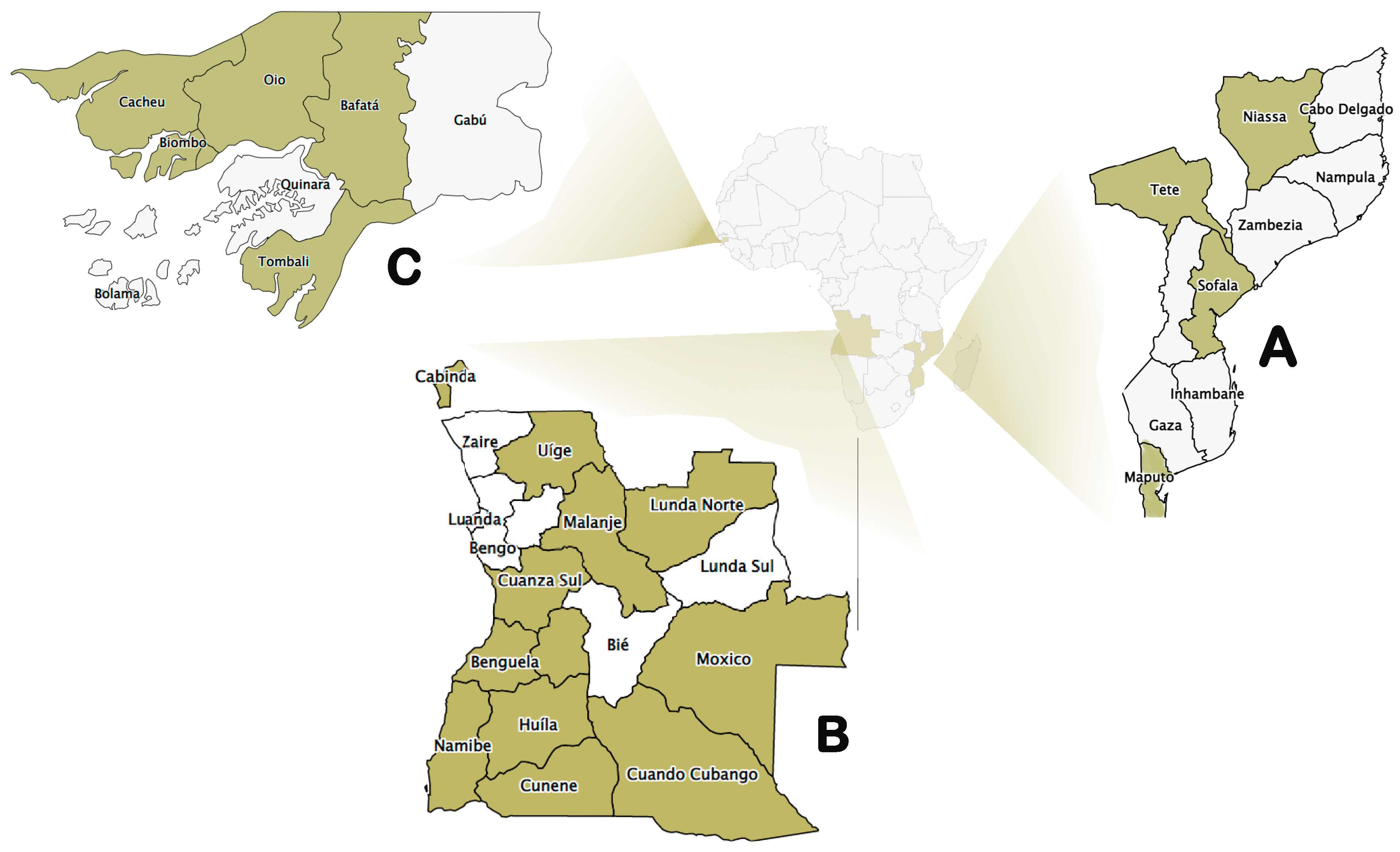

- Brief geographical and ecological description and the mammal diversity in the sub-Saharan countries: Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau

- (i)

- Mozambique

- (ii)

- Angola

- (iii)

- Guinea-Bissau

- 2.

- The Small Mammal Collection

- (i)

- Each specimen was individually checked for labelling information, and corrections were made to the museum databases and digitized records when warranted;

- (ii)

- Specimens with missing information, particularly regarding species-level taxonomic identification, were discarded from the final description list and subsequent analyses unless this information could be completed;

- (iii)

- (iv)

- (v)

- Localities of occurrence were reviewed and, when needed, were updated to the current designation, using the GeoNames database (https://www.geonames.org/, accessed on 20 March 2025);

- (vi)

- To produce the final list, species were arranged alphabetically according to the hierarchy of taxonomic orders and families.

- 3.

- Completeness of the Collection

3. Results

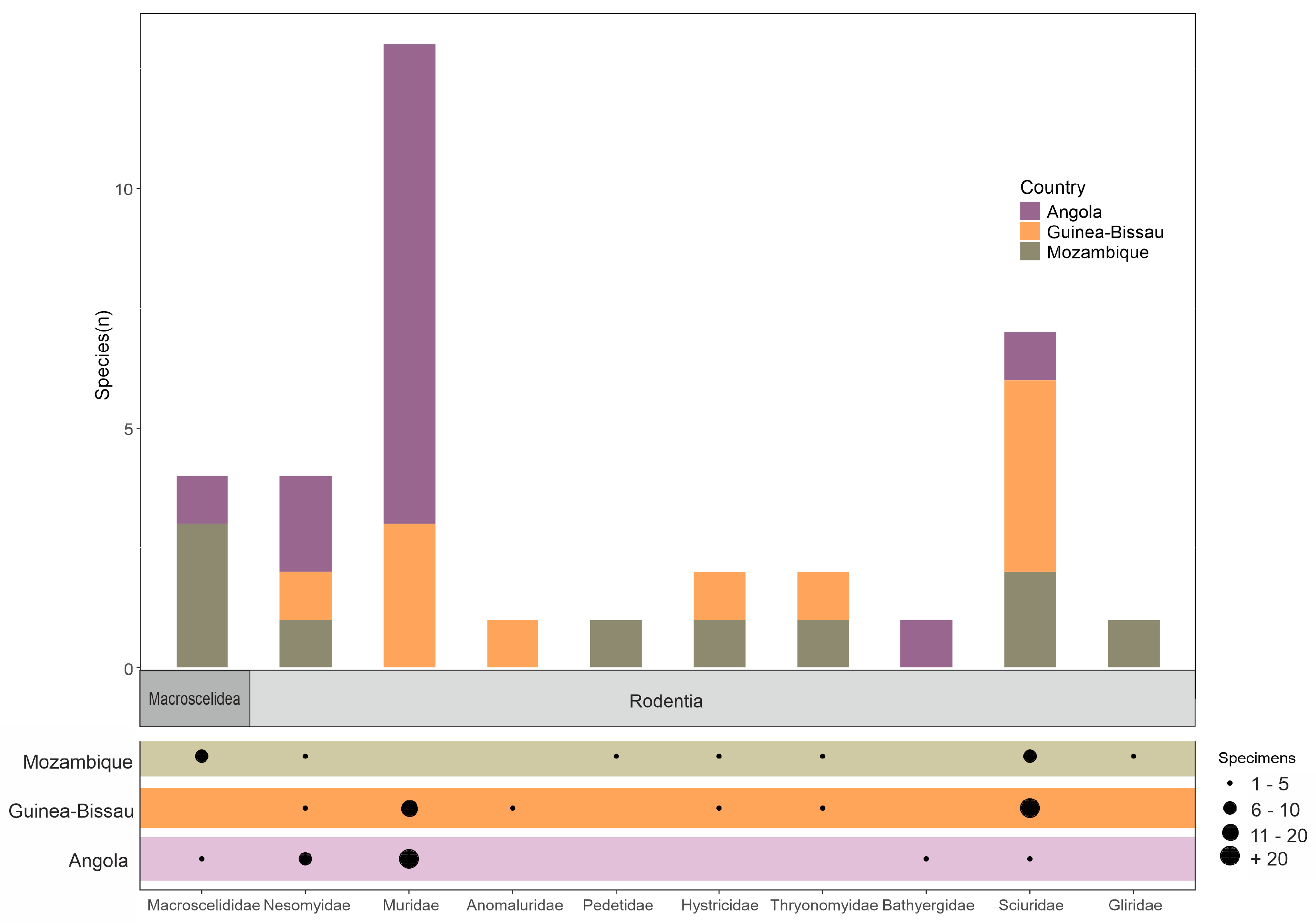

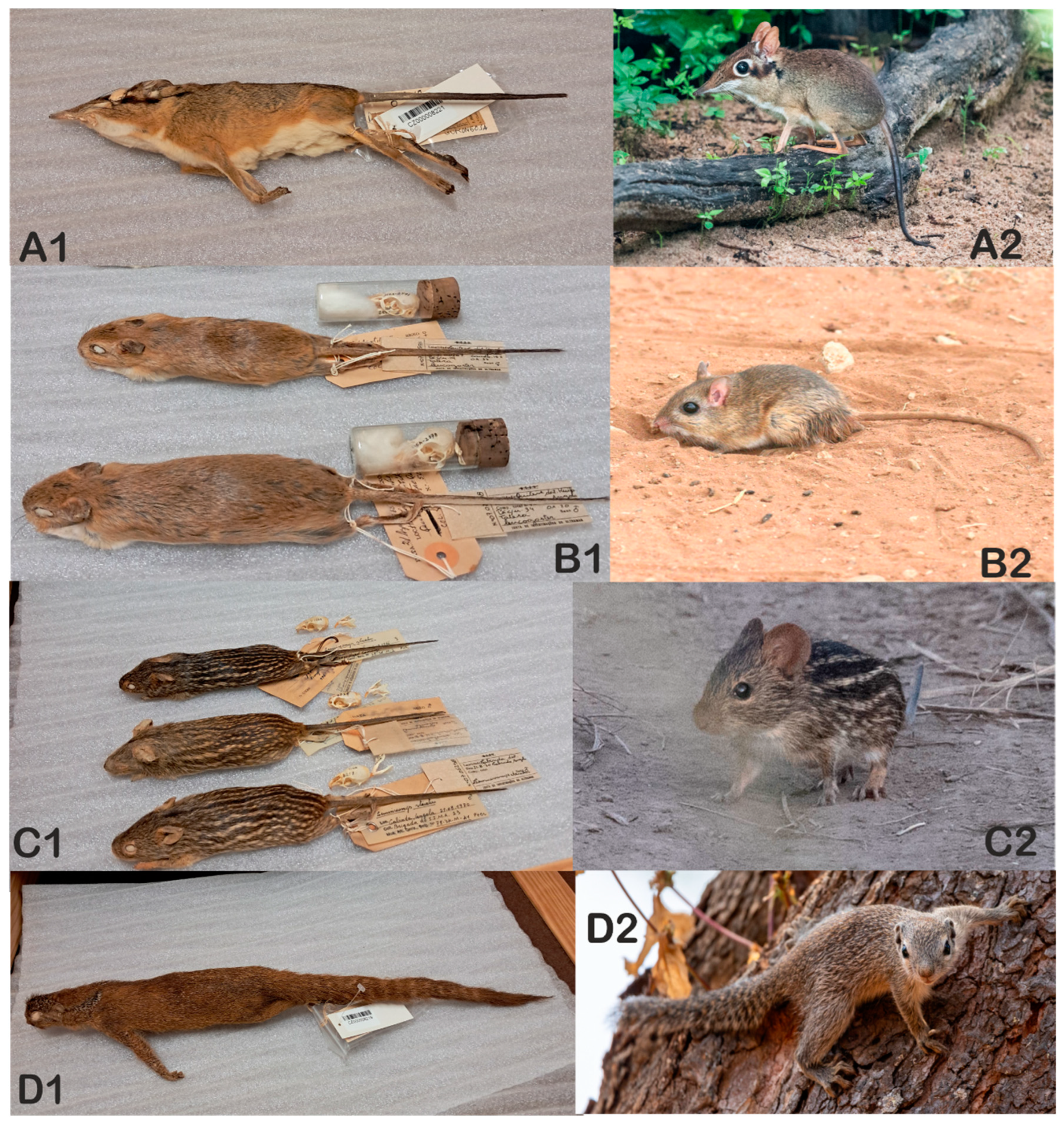

3.1. The Sub-Saharan Mammal Collection

General Overview

3.2. Country Accounts

- (i)

- Mozambique

- (ii)

- Angola

- (iii)

- Guinea-Bissau

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amano, T.; Sutherland, W.J. Four Barriers to the Global Understanding of Biodiversity Conservation: Wealth, Language, Geographical Location and Security. Proc. R. Soc. B 2013, 280, 20122649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amori, G.; Masciola, S.; Saarto, J.; Gippoliti, S.; Rondinini, C.; Chiozza, F.; Luiselli, L. Spatial Turnover and Knowledge Gap of African Small Mammals: Using Country Checklists as a Conservation Tool. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1755–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, A.M. Natural History Collections as Sources of Long-Term Datasets. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, M.W.; Hammond, T.T.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Walsh, R.E.; LaBarbera, K.; Wommack, E.A.; Martins, F.M.; Crawford, J.C.; Mack, K.L.; Bloch, L.M.; et al. Natural History Collections as Windows on Evolutionary Processes. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 864–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, E.W.; Peterhans, J.C.K.; Yonas, M. Leaving More than a Legacy: Museum Collection Reveals Small Mammal Climate Responses in Ethiopian Highlands. In Proceedings of the 98th Meeting of the American Society of Mammalogists, Manhattan, KS, USA, 25–29 June 2018; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Monfils, A.K.; Krimmel, E.R.; Bates, J.M.; Bauer, J.E.; Belitz, M.W.; Cahill, B.C.; Caywood, A.M.; Cobb, N.S.; Colby, J.B.; Ellis, S.A.; et al. Regional Collections Are an Essential Component of Biodiversity Research Infrastructure. BioScience 2020, 70, 1045–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldså, J.; Burgess, N.D.; Blyth, S.; De Klerk, H.M. Where Are the Major Gaps in the Reserve Network for Africa’s Mammals? Oryx 2004, 38, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. State of Biodiversity in Africa; United Nations Environment Programme: Cambridge, UK, 2010; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, E.R.; Dziba, L.; Mulongoy, K.; Maoela, M.A.; Walters, M. The IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Africa; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2018; p. 492. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, W.C.H. Lista de Mammiferos Das Possessões Portuguezas Da Africa Occidental e Diagnoses de Algumas Especies Novas. J. Sci. Math. Phys. E Naturaes 1870, 3, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa du Bocage, J.V. Chiroptéres Africains Nouveaux, Rares Ou Peu Connus. J. Sci. Math. Phys. E Naturaes 1889, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa du Bocage, J.V. Liste Des Antilopes d’Angola. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1878, 46, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa du Bocage, J.V. Sur Une Nouvelle Espèce de Cynonycteris d’Angola. J. Sciências Mathemáticas Phys. E Naturaes 1898, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Frade, F. Notas de Zoogeografia e de História das Explorações Faunísticas da Guiné Portuguesa; Estudos, Ensaios e Documentos, Ministério das Colónias: Lisboa, Portugal, 1950; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Frade, F. Linhas Gerais Da Distribuição Geográfica Dos Vertebrados Em Angola. Mem. Junta De Investig. Do Ultramar 1963, 43, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, O.; Wroughton, R. XVIII.—On a Second Collection of Mammals Obtained by Dr. WJ Ansorge in Angola. J. Nat. Hist. 1905, 16, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Frade, F.; Silva, J. Mamıferos Da Guiné (Colecçao Do Centro de Zoologia). Garcia Orta Série Zool. 1980, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford-Cabral, J. Projecto Estudo do Parque Natural das Lagoas da Cufada (Guiné-Bissau), 2a Missão Zoológica, Relatório Específico Sobre a Fauna de Mamíferos; lnstituto de Investigação Científica Tropical: Lisboa, Portugal, 1998; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, M. As Missões Zoológicas e a Zoologia Tropical. In Viagens e Missões Científicas nos Trópicos 1883–2010; Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010; pp. 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Primack, R.; Wilson, J.W. Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 1-78374-753-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, J.; Couto, M.; Oglethorpe, J. Biodiversity and War: A Case Study of Mozambique; Biodiversity Support Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Guinea-Bissau. Strategy and National Action Plan for the Biodiversity 2015–2020; The State’s General Office of the Environment: Konakry, Guinea, 2015; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, I.Q.; Da Luz Mathias, M.; Bastos-Silveira, C. The Terrestrial Mammals of Mozambique: Integrating Dispersed Biodiversity Data. Bothalia 2018, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, I.Q.; Mathias, M.D.L.; Bastos-Silveira, C. Mapping Knowledge Gaps of Mozambique’s Terrestrial Mammals. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beja, P.; Vaz Pinto, P.; Veríssimo, L.; Bersacola, E.; Fabiano, E.; Palmeirim, J.M.; Monadjem, A.; Monterroso, P.; Svensson, M.S.; Taylor, P.J. The Mammals of Angola. In Biodiversity of Angola: Science & Conservation: A Modern Synthesis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 357–443. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Roadmap for the Conservation of Leopards in Africa; IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group: Gland, Switzerland, 2019; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Lewison, R.; Pluháček, J. Report of the Hippo Specialist Group; IUCN SSC and Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2024; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Itoua, I.; Strand, H.; Morrison, J.; Loucks, C.; Allnutt, T.; Ricketts, T.; Kura, Y.; Lamoreux, J.; Wettengel, W.; Hedao, P. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth. BioScience 2001, 51, 933938. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, F.; Simões, A.P. Mamíferos Selvagens da Guiné-Bissau; Projecto Delfim, Centro Portuguûes de Estudos dos Mamíferos Marinhos: Lisboa, Portugal, 1998; ISBN 972-98180-0-2. [Google Scholar]

- De Nóbrega, Á.C. A Luta Pelo Poder Na Guiné-Bissau; Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003; ISBN 972-8726-19-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sangreman, C.; de Sousa, F., Jr.; Zeverino, G.; Barros, M. A Evolução Política Recente Na Guiné-Bissau: As Eleições Presidenciais de 2005, Os Conflitos, o Desenvolvimento, a Sociedade Civil; ISEG—CesA: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Lacher, T.E.; Mittermeier, R.A. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume 7: Rodents II; Lynx: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-16728-04-6. [Google Scholar]

- Burgin, C.J.; Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Rylands, A.B.; Lacher, T.E.; Sechrest, W. Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World; Volume I Monotremata to Rodentia; Lynx: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; ISBN 84-16728-35-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mammal Diversity Database. Mammal Diversity Database (v2.2); The American Society of Mammalogists: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Happold, D. Mammals of Africa; Volume III: Rodents, Hares and Rabbits; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-399-42033-4. [Google Scholar]

- Loggins, A.A.; Monadjem, A.; Kruger, L.M.; Reichert, B.E.; McCleery, R.A. Vegetation Structure Shapes Small Mammal Communities in African Savannas. J. Mammal. 2019, 100, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbun, G.B. Elephantulus brachyrhynchus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T42658A21288656; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M. Rhynchocyon birnei. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T19709A166489513; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.R.; Rathbun, G.B. Petrodromus Tetradactylus. Mamm. Species 2001, 2001, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbun, G.B.; FitzGibbon, C. Petrodromus tetradactylus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T42679A21290893; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F.; Child, M.F. Saccostomus campestris. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T19808A115153363; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmess, E.L. Hystrix africaeaustralis. Mamm. Species 2006, 2006, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinke, D.; Brown, C. Habitat Use by the Southern Springhare (Pedetes capensis) in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 2006, 36, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cassola, F.; IUCN. Hystrix africaeaustralis. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T10748A115099085; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Child, M.F. Thryonomys swinderianus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21847A115163896; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, M.F. Pedetes capensis. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T16467A115133584; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F. Paraxerus palliatus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T16210A115132374; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F. Paraxerus cepapi. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T16205A115131842; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F.; Child, M.F. Graphiurus murinus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T9487A115093727; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, M.F.; Monadjem, A. Steatomys pratensis. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T20722A115159593; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Kennerley, R. Dasymys nudipes. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T6271A22436918; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.D.; Hill, J.E.; Expedition, P.-B.; Expedition, V.A. The Mammals of Angola, Africa. Bull. AMNH 1941, 78, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Verheyen, W.; Hulselmans, J.; Dierckx, T.; Colyn, M.; Leirs, H.; Verheyen, E. A Craniometric and Genetic Approach to the Systematics of the Genus Dasymys PETERS, 1875 and the Description of Three New Taxa (Rodentia, Muridae, Africa). Bull. L’institut R. Sci. Nat. Belg. 2003, 73, 27–72. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford-Cabral, J. The Angolan Rodents of the Superfamily Muroidea: An Account of Their Distribution; Estudos, ensaios e documents; Ministério da Ciência e da Tecnologia, Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical: Lisboa, Portugal, 1998; ISBN 978-972-672-865-8. [Google Scholar]

- Granjon, L. Mastomys natalensis. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T12868A115107375; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leirs, H.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Sluydts, V.; Sabuni, C.; Borremans, B.; Katakweba, A.; Massawe, A.; Makundi, R.; Mulungu, L.; Machang’u, R.; et al. Twenty-Nine Years of Continuous Monthly Capture-Mark-Recapture Data of Multimammate Mice (Mastomys natalensis) in Morogoro, Tanzania. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Straeten, E.; Decher, J.; Corti, M.; Abdel-Rahman, E.H. Lemniscomys striatus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T11495A134928061; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F. Lemniscomys griselda. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T11489A115102674; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, S.; Faulkes, C. Fukomys mechowi. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T5756A22185092; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F. Funisciurus congicus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T8758A115088669; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Dasymys incomtus (Errata Version Published in 2017). In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T6269A115080446; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granjon, L. Arvicanthis ansorgei. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granjon, L. Uranomys ruddi. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22771A22400326; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, M.D.; Waterman, J.M. Xerus erythropus. Mamm. Species 2004, 748, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cassola, F. Funisciurus pyrropus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T8762A115089084; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F. Heliosciurus rufobrachium. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T9833A115095080; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amori, G.; De Smet, K. Hystrix cristata. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T10746A22232484; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giarla, T.C.; Demos, T.C.; Monadjem, A.; Hutterer, R.; Dalton, D.; Mamba, M.L.; Roff, E.A.; Mosher, F.M.; Mikeš, V.; Kofron, C.P.; et al. Integrative Taxonomy and Phylogeography of Colomys and Nilopegamys (Rodentia: Murinae), Semi-Aquatic Mice of Africa, with Descriptions of Two New Species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 192, 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.A.; Abernathy, K.; Chapman, L.J.; Downs, C.; Effiom, E.O.; Gogarten, J.F.; Golooba, M.; Kalbitzer, U.; Lawes, M.J.; Mekonnen, A.; et al. The Future of Sub-Saharan Africa’s Biodiversity in the Face of Climate and Societal Change. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 790552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Chapman, C.A.; Pimm, S.L.; Turvey, S.T.; Lawes, M.J.; Peres, C.A.; Lee, T.M.; Fan, P. Regional Scientific Research Benefits Threatened-Species Conservation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2019, 6, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford-Cabral, J. Some New Data on Angolan Muridae. Zool. Afr. 1966, 2, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford-Cabral, J. Relatório da Deslocação à Guiné-Bissau 1990; Relatório Interno do IICT: Lisboa, Portugal, 1990; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.J.; Whittaker, R.J. Review: On the Species Abundance Distribution in Applied Ecology and Biodiversity Management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niquisse, S.; Cabral, P.; Rodrigues, Â.; Augusto, G. Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity Trends in Mozambique as a Consequence of Land Cover Change. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacar, F.F.; Faque, H.B. Forest Holds High Rodent Diversity than Other Habitats under a Rapidly Changing and Fragmenting Landscape in Quirimbas National Park, Mozambique. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamba, M.L.; Da Conceição, A.G.; Naskrecki, P.; Ngovene, A.; Dalton, D.L.; Russo, I.-R.M.; Visser, F.; Monadjem, A. An Annotated Checklist of the Mammals of the Chimanimani National Park, Mozambique. CheckList 2024, 20, 1222–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, M.D.; Banasiak, R.A.; Stanley, W.T. A New Species of the Rodent Genus Hylomyscus from Angola, with a Distributional Summary of the H. Anselli Species Group (Muridae: Murinae: Praomyini). Zootaxa 2015, 4040, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntley, B.J. Ecology of Angola: Terrestrial Biomes and Ecoregions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-18922-7. [Google Scholar]

- Huntley, B.J.; Beja, P.; Vaz Pinto, P.; Russo, V.; Veríssimo, L.; Morais, M. Biodiversity Conservation: History, Protected Areas and Hotspots. In Biodiversity of Angola; Huntley, B.J., Russo, V., Lages, F., Ferrand, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 495–512. ISBN 978-3-030-03082-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bout, N.; Ghiurghi, A. Guide des Mamiferes du Parc National de Cantanhez; Acção Para o Desenvolvimento, Guinée-Bissau & Associazione Interpreti Naturalistici ONLUS: Teramo, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, R.; Westra, S. Small Terrestrial Mammal and Amphibian Survey Boé Region, Guinea-Bissau; Silvavir Forest Consultants: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2015; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Rainho, A.; Palmeirim, J. Mamíferos Terrestres. In Parque Nacional Marinho João Vieira e Poilão: Biodiversidade e Conservação; IPAB: Bissau, Republic of Guinea-Bissau, 2018; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Granjon, L. Arvicanthis niloticus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponder, W.F.; Carter, G.A.; Flemons, P.; Chapman, R.R. Evaluation of Museum Collection Data for Use in Biodiversity Assessment. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Family | Previous Lists * | Final List # | MUHNAC Species | Completeness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mozambique | |||||

| Macroscelidea N = 5 | Macroscelididae | 5 | 5 | 3 | 60 |

| Rodentia N = 53 | Nesomyidae | 8 | 9 | 1 | 11.1 |

| Muridae | 27 | 29 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anomaluridae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pedetidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

| Hystricidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

| Thryonomyidae | 2 | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

| Bathyergidae | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sciuridae | 5 | 5 | 2 | 40 | |

| Gliridae | 3 | 3 | 1 | 33.3 | |

| Angola | |||||

| Macroscelidea N = 2 | Macroscelididae | 3 | 2 | 1 | 50 |

| Rodentia N = 89 | Nesomyidae | 15 | 15 | 2 | 13 |

| Muridae | 48 | 52 | 10 | 19 | |

| Anomaluridae | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pedetidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hystricidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Thryonomyidae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bathyergidae | 2 | 2 | 1 | 50 | |

| Petromuridae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sciuridae | 9 | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | |

| Gliridae | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | |||||

| Rodentia N = 28 | Anomaluridae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Nesomyidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

| Muridae | 7 | 17 | 3 | 18 | |

| Hystricidae | 1 | 2 | 1 | 50 | |

| Thryonomyidae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

| Sciuridae | 4 | 4 | 4 | 100 | |

| Gliridae | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Order/Family | Species | Common Name | IUCN | Trend | Location Province/Region | Location Locality and Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mozambique | ||||||

| MACROSCELIDEA | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus (Smith 1836) | Short-snouted sengi | LC | NK | LNK (3) | |

| Macroscelididae | Rhynchocyon cirnei (Peters 1847) | Chequered sengi | LC | D | Niassa (1) | LNK (1) |

| Petrodromus tetradactylus (Peters 1846) | Four-toed sengi | LC | NK | Sofala (4) | Gorongosa (4) 18°40′32″ S/34°4′22″ E | |

| RODENTIA Pedetidae | Pedetes capensis (Forster 1778) | Spring hare | LC | NK | LNK (4) | |

| Nesomyidae | Saccostomus cf.campestris (Peters 1846) | South African pouched mouse | LC | S | Sofala (1) | Gorongosa (1) 18°40′32″ S/34°4′22″ E |

| Hystricidae | Hystrix africaeaustralis (Peters 1852) | Cape porcupine | LC | S | LNK (1) | |

| Thryonomyidae | Thryonomys swinderianus (Temminck 1827) | Greater cane rat | LC | NK | Maputo (2) | Maputo (2) 25°57′55″ S/32°34′59″ E |

| Sciuridae | Heliosciurus gambianus (Ogilby 1835) | Gambian sun squirrel | LC | NK | Sofala (1) | Gorongosa (1) 18°40′32″ S/34°4′22″ E |

| Paraxerus cepapi (A. Smith 1836) | Smith’s bush squirrel | LC | S | LNK (2) | ||

| Paraxerus palliates (Peters 1852) | Red bush squirrel | LC | NK | LNK (4) | ||

| Gliridae | Graphiurus murinus (Desmarest 1822) | Woodland dormouse | LC | S | Maputo (1) | Maputo (1) 25°57′55″ S/32°34′59″ E |

| Angola | ||||||

| MACROSCELIDEA Macroscelididae | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus (Smith 1836) | Short-snouted sengi | LC | NK | Moxico (2) | Cameia (2) 11°41′26″ S/20°50′21″ E |

| RODENTIA Nesomyidae | Saccostomus cf. campestris (Peters 1846) | Southern african pouched mouse | LC | S | Huambo (1) | Calombe (1) 11°50′16″ S/19°55′3″ E |

| Steatomys pratensis (Peters 1846) | Fat mouse | LC | S | Moxico (4) | Cameia (4) 11°41′26″ S/20°50′21″ E | |

| Lunda Norte (1) | LNK(1) | |||||

| Muridae | Aethomys kaiseri (Noak 1887) | Kaiser’s rock rat | LC | NK | Malanje (2) | Quimbango (1) 10°57′49″ S/17°34′28″ E Mulundo (1) 11°23′18″ S/17°43′47″ E |

| Aethomys thomasi (de Winton 1897) | Thomas’s rock rat | LC | NK | Huíla (3) | Humpata (3) 15°4′21″ S/13°22′3″ E | |

| Cuando Cubango (10) | Cuchi (10) 14°38′14″ S/16°57′39″ E | |||||

| Dasymys cf. incomtus (Sundevall 1847) | African marsh rat | LC | NK | Malanje (5) | Quimbango (5) 10°57′49″ S/17°34′28″ E | |

| Cuanza Sul (6) | Mussende (6) 10°12′46″ S/15°58′34″ E | |||||

| Huambo (2) | Massano de Amorim (2) 12°21′13″ S/15°6′8″ E | |||||

| Cuando Cubango (1) | Dirico (1) 17°30′0″ S/20°50′0″ E | |||||

| Dasymys nudipes (Peters 1870) | Angolan shaggy rat | DD | NK | Cuando Cubango (4) | Dirico (1) 17°30′0″ S/20°50′0″ E Cuchi (3) 14°38′14″ S/16°57′39″ E | |

| Huíla (7) | LNK (1) Cuvango (1) 14°27′56″ S/16°17′32″ E Humpata (5) 15°4′21″ S/13°22′3″ E | |||||

| Huambo (1) | Massano de amorim (1) 12°21′13″ S/15°6′8″ E | |||||

| Gerbilliscus leucogaster (Peters 1852) | Bushveld gerbil | LC | S | Huíla (19) | Humpata (8) 15°4′21″ S/13°22′3″ E Quiteve (11) 16°1′4″ S/15°11′6″ E | |

| Malanje (11) | Quimbango (2) 10°57′49″ S/17°34′28″ E Mulundo (9) 11°23′18″ S/17°43′47″ E | |||||

| Cunene (10) | Naulila (10) 17°12′6″ S/14°40′50″ E | |||||

| Namibe (9) | Moçamedes (9) 15°11′46″ S/12°9′8″ E | |||||

| Benguela (1) | Farta (1) 13°8′54″ S/13°6′16″ E | |||||

| Moxico (3) | Cameia (1) 11°41′26″ S/20°50′21″ E Lago Dilolo (2) 11°30′15″ S/22°0′52″ E | |||||

| Gerbilliscus validus (Bocage 1890) | Savanna gerbil | LC | S | Malanje (14) | Luando (2) 11°0′51″ S/17°39′9″ E Quimbango (13) 10°57′49″ S/17°34′28″ E | |

| Lemniscomys griselda (Thomas 1904) | Griselda’s striped grass mouse | LC | S | Cunene (1) | Nehome (1) | |

| Huila (6) | LNK (2) Quiteve (4) 16°1′4″ S/15°11′6″ E | |||||

| Malanje (8) | Quimbango (4) 10°57′49″ S/17°34′28″ E Mulundo (2) 11°23′18″ S/17°43′47″ E Xandel (2) 9°23′11″ S/17°11′39″ E | |||||

| Cuanza Sul (7) | LNK (1) Cariango (2) 10°34′50″ S/15°19′46″ E Carilahongo (1) 10°45′45″ S/14°15′27″ E Ebo (1) 10°55′45″ S/14°44′41″ E Ipumba (1) 10°45′16″ S/14°12′6″ E Seles (1) 11°29′54″ S/14°29′23″ E | |||||

| Benguela (1) | Chongoroi (1) 13°35′21″ S/13°48′44″ E | |||||

| Moxico (3) | Calombe (1) 11°50′16″ S/19°55′3″ E Cameia (2) 11°41′26″ S/20°50′21″ E | |||||

| Lemniscomys striatus (Linnaeus 1758) | Typical striped grass mouse | LC | I | Uíge (20) | LNK (2) 31 de Janeiro (1) 6°53′53″ S/15°19′26″ E Banza Tumba(1) 6°28′28″ S/14°59′50″ E Cabinda (7) 7°19′20″ S/15°5′19″ E Lucunga (1) 7°34′0″ S/15°17′0″ E Negage (6) 7°45′33″ S/15°16′19″ E Quitexe (1) 7°56′24″ S/15°2′26″ E Songo (1) 7°8′0″ S/14°47′21″ E | |

| Malanje (4) | Xandel (2) 9°23′11″ S/17°11′39″ E Quizenga (2) 6°47′40″ S/15°31′49″ E | |||||

| Cabinda (5) | Cabinda (5) 5°33′43″ S/12°11′41″ E | |||||

| Moxico (4) | Calombe (1) 11°50′16″ S/19°55′3″ E Cameia (3) 11°41′26″ S/20°50′21″ E | |||||

| Pelomys fallax (Peters 1852) | Creek groove-toothed swamp rat | LC | NK | Moxico (1) | Cameia (3) 11°41′26″S/20°50′21″ E | |

| Bathyergidae | Fukomys mechowii (Peters 1881) | Mechow’s mole-rat | LC | S | Moxico (1) | Calombe (1) 11°50′16″ S/19°55′3″ E |

| Sciuridae | Funisciurus congicus (Kuhl 1820) | Congo rope squirrel | LC | S | LNK (1) | |

| Guinea-Bissau | ||||||

| RODENTIA Anomaluridae | Anomalurus beecrofti (Fraser 1853) | Beecroft’s scaly-tailed squirrel | LC | NK | LNK (1) | |

| Nesomyidae | Cricetomys gambianus (Waterhouse 1840) | Northern giant pouched rat | LC | S | Tombali (1) | Cacine (1) 11°7′0″ N/15°1′0″ W |

| LNK (2) | ||||||

| Muridae | Arvicanthis ansorgei (Thomas 1910) | Sudanian grass rat | LC | NK | Biombo (4) | Tor (4) 11°51′0″ N/15°54′0″ W |

| Cacheu (1) | Canchungo (1) 12°26′0″ N/16°5′0″ W | |||||

| Mastomys natalensis (Smith 1834) | Natal multimammate mouse | Biombo (1) | Tor (1) 11°51′0″ N/15°54′0″ W | |||

| Bafatá (1) | Chitole (1) 11°44′0″ N/14°49′0″ W | |||||

| Cacheu (4) | Canchungo (4) 12°26′0″ N/16°5′0″ W | |||||

| Tombali (1) | Cacine (1) 11°7′0″ N/15°1′0″ W | |||||

| LNK (2) | ||||||

| Uranomys ruddi (Dollman 1909) | Rudd’s mouse | LC | D | Oio (1) | Bissorã (1) 12°13′23″ N/15°26′51″ W | |

| Hystricidae | Hystrix cristata (Linnaeus 1758) | Crested porcupine | LC | NK | Bissau (2) | Bissau (2) 11°51′48″ N/15°35′51″ W |

| Thryonomyidae | Thryonomys swinderianus (Temminck 1827) | Greater cane rat | LC | NK | LNK (2) | |

| Sciuridae | Funisciurus pyrropus (F. Cuvier 1833) | Fire-footed rope squirrel | LC | S | LNK (4) | |

| Heliosciurus gambianus (Ogilby 1835) | Gambian sun squirrel | LC | NK | Bafatá (2) | LNK (2) | |

| LNK (23) | ||||||

| Heliosciurus rufobrachium (Waterhouse 1842) | Red-legged sun squirrel | LC | NK | LNK (7) | ||

| Bafatá (1) | LNK (1) | |||||

| Oio (1) | LNK (1) | |||||

| Xerus erythropus (Desmarest 1817) | Striped ground squirrel | LC | NK | Biombo (1) | Tor (1) 11°51′0″ N/15°54′0″ W | |

| LNK (15) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathias, M.d.L.; Monarca, R.I. African Small Mammals (Macroscelidea and Rodentia) Housed at the National Museum of Natural History and Science (University of Lisbon, Portugal). Diversity 2025, 17, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070485

Mathias MdL, Monarca RI. African Small Mammals (Macroscelidea and Rodentia) Housed at the National Museum of Natural History and Science (University of Lisbon, Portugal). Diversity. 2025; 17(7):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070485

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathias, Maria da Luz, and Rita I. Monarca. 2025. "African Small Mammals (Macroscelidea and Rodentia) Housed at the National Museum of Natural History and Science (University of Lisbon, Portugal)" Diversity 17, no. 7: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070485

APA StyleMathias, M. d. L., & Monarca, R. I. (2025). African Small Mammals (Macroscelidea and Rodentia) Housed at the National Museum of Natural History and Science (University of Lisbon, Portugal). Diversity, 17(7), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070485