A History of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Implementation in Nepal

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. CITES in Nepal

3. Research Framework

3.1. Nepal’s CITES Act, 2017, and Regulations

“…We have enough laws to implement CITES, and now, by enacting CITES, 2017, we have made the use of natural resources so complex that even collecting wild vegetables can be in the same basket as wildlife-related crimes …. poor people suffer while following traditional practices. Crime should be seen in relative terms. I was not in favor of the CITES Act, 2017.”KI from the Ministry of Forests and Environment

“….In Nepal, we follow the rules and regulations and often create stricter regulations, though we don’t have the mechanism to check whether the actuated rules and regulations are either working properly or need changes based on evidence.”KI from DoFSC

“…The most important challenge for implementing CITES is that the 2017 Act is federal and the Division Forests Offices are under provincial governments; that is why we cannot get easy access to data on traded species from some districts. When we ask about data, they don’t send it; the Division Forest Offices are not under the DoFSC chain of command. So, the federal system is a hurdle for the implementation of these laws and policies.”KI from DOFSC

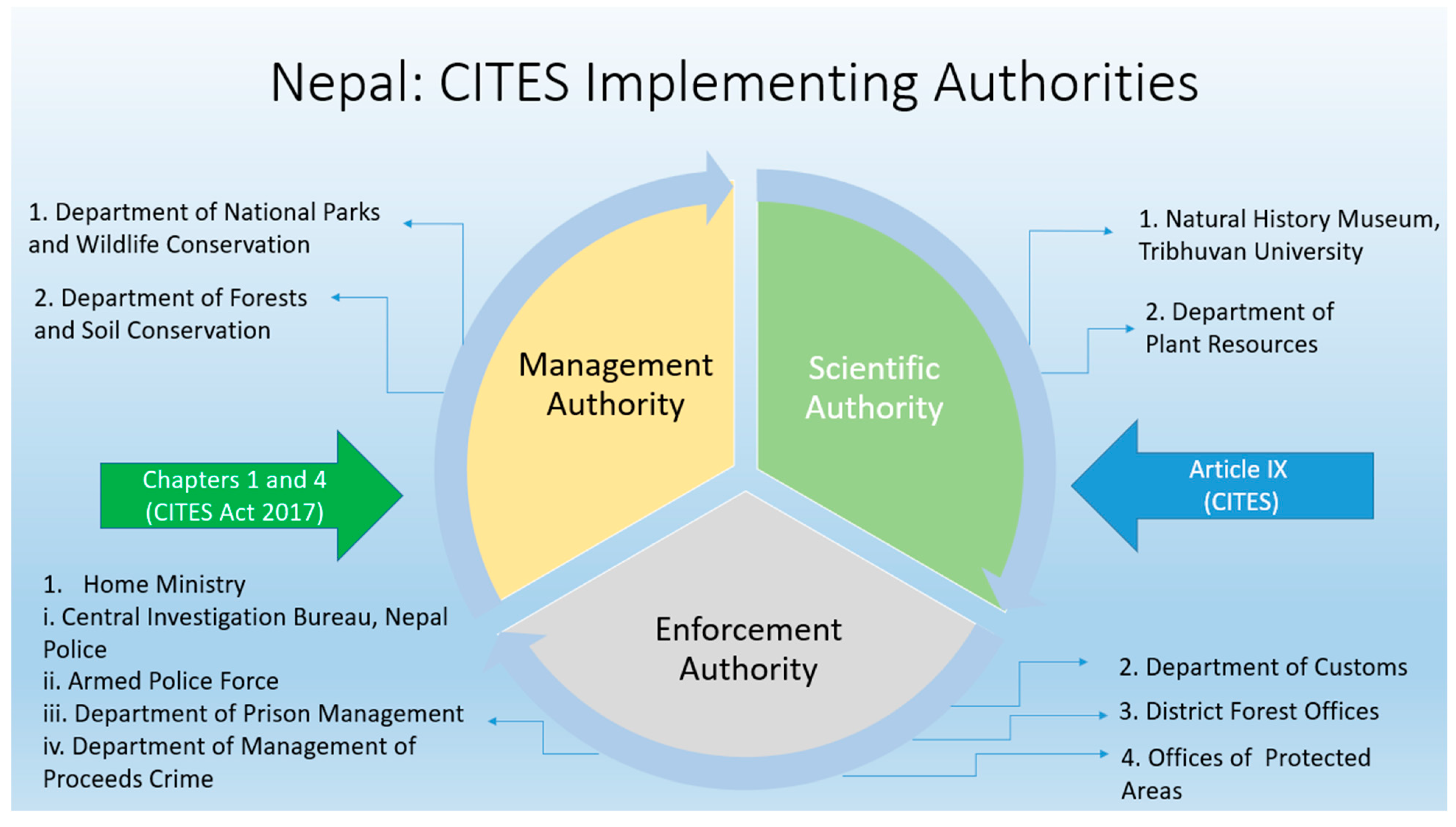

3.2. CITES-Implementing Authorities and Their Responsibilities

“…Our role on behalf of NHM is to give suggestions, feedback, and consultation related to fauna to the Government of Nepal. District Forest Offices (previously) now changed to Division Forest Offices (DFOs) are responsible for enforcing CITES. DFOs collect live wildlife or body parts confiscated by the Central Investigation Bureau. The CIB arrests people who trade in wildlife and specimens are brought to us for identification. We issue a letter after identification and the case is registered”.KI from NHM

“…The permission for CITES-related documents on plant resources used to be provided by DPR, but now, this responsibility is given to DoFSC. The responsibility of DPR is to provide advice and suggestions related to plants on the CITES list”.KI from DPR

“…There are regular meetings with the DPR and the DNPWC as necessary. These meetings can be formal, with “minutes.” However, we don’t sit in meetings with the scientific authority on fauna”.KI from the DoFSC

“…we have not yet held CITES Coordination meeting as provisioned in the CITES Act 2017”.KI from DNPWC

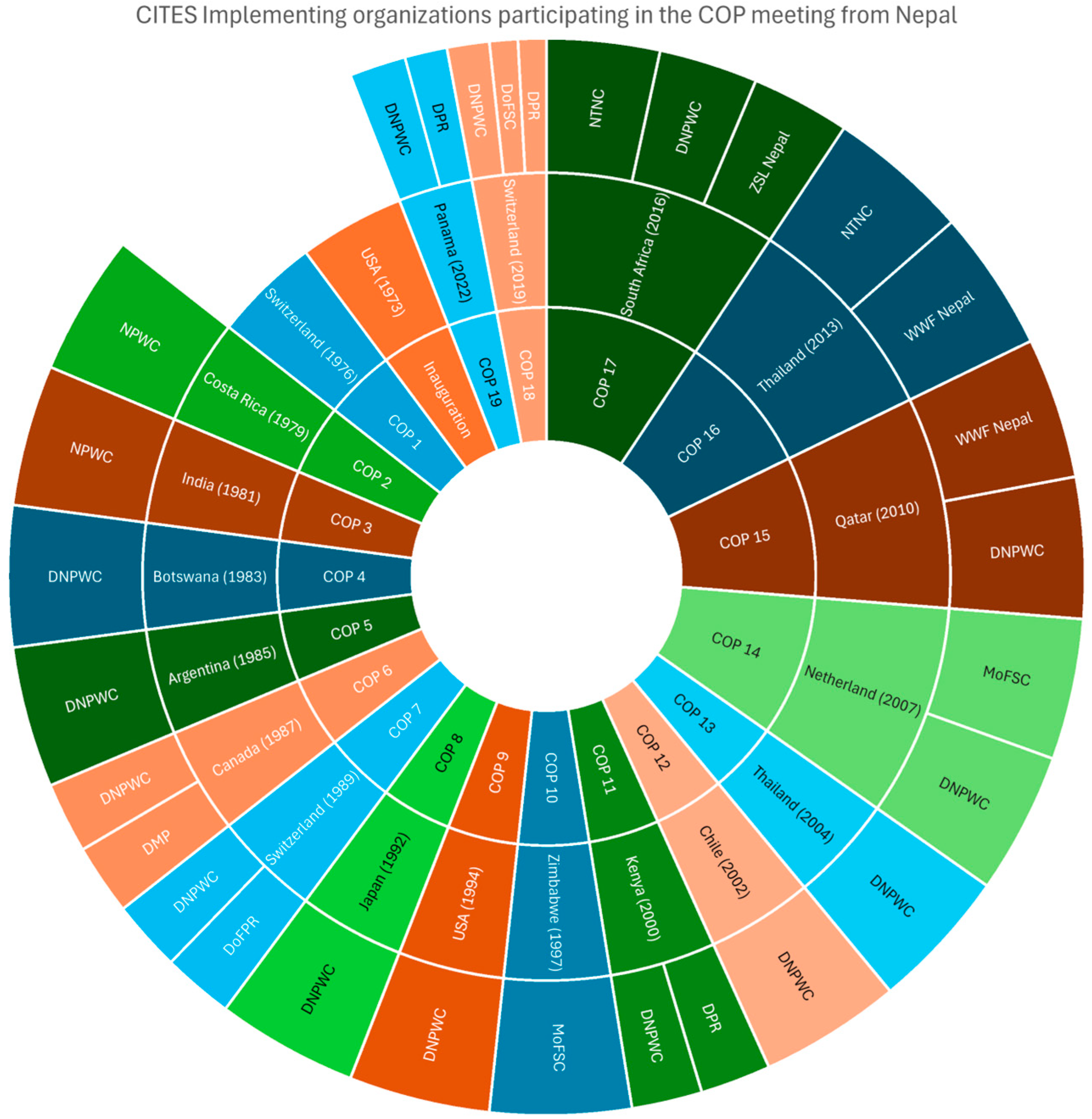

3.3. Nepal’s Participation in CITES Conferences of Parties (COPs)

“…The fact is we (NHM) do not get direct invitations to the meeting. The invitation is sent to the management authority of CITES or to the Ministry, and participants are selected from there.”KI from NHM

“….Meetings are mostly attended by management authorities as there are only two invitees from the CITES Secretariat and any further delegations need to be sponsored by the government. …delegates from the Ministry and the DNPWC participate, but in recent years, the issue has been raised about NHM not participating.”KI from the Ministry of Forests and Environment

“…. I participated in CoP 18 and 19. We published a checklist of CITES listed plants and we also had the 2017 Act by then. We requested a budget from the government a year prior, which was accepted, and I was able to participate in the CoP meeting”.KI from DPR mentioning their achievements after enacting the CITES Act

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cites.org. What Is CITES? Available online: https://cites.org/eng/disc/what.php (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- IUCN. Resolutions Adopted by the General Assembly. In Proceedings of the Seventh General Assembly, Warsaw, Poland, 15–24 June 1960; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Secretary General’s Report 1960–1963. In Proceedings of the Eighth General Assembly, Nairobi, Kenya, 16–24 September 1964; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Resolutions adopted by the Tenth General Assembly of IUCN. In Proceedings of the Tenth General Assembly, New Delhi, India, 24 November–1 December 1970; Volume 2, p. 908. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, M. A Tale of Two CITES: Divergent Perspectives upon the Effectiveness of the Wildlife Trade Convention. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2013, 22, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, A.J.; Gratwicke, B.; Hepburn, C.; Herrera, E.A.; Macdonald, D.W. Tackling Unsustainable Wildlife Trade. Key Top. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 2, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cites.org. List of Parties to the Convention. Available online: https://cites.org/eng/disc/parties/index.php (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Korwin, S.; Denier, L.; Lieberman, S.; Reeve, R. Verification of Legal Acquisition under the CITES Convention: The Need for Guidance 541 on the Scope of Legality. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2019, 22, 274–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klemm, C. Guidelines for Legislation to Implement CITES; IUCN—The World Conservation Union: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 1993; ISBN 2831701163. [Google Scholar]

- Cites.org. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Available online: https://cites.org/eng/disc/text.php#IX (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Heinen, J.T.; Chapagain, D.P. On the Expansion of Species Protection in Nepal: Advances and Pitfalls of New Efforts to Implement and 539 Comply with CITES. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2002, 5, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, D. Debate within the CITES Community: What Direction for the Future? Nat. Resour. J. 1993, 33, 875–918. [Google Scholar]

- Couzens, E. CITES at Forty: Never Too Late to Make Lifestyle Changes. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2013, 22, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez Gomar, J.O.; Stringer, L.C. Moving Towards Sustainability? An Analysis of CITES’ Conservation Policies. Environ. Policy Gov. 2011, 21, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.S.; Harrop, S.R.; MacMillan, D.C. Understanding Markets to Conserve Trade-Threatened Species in CITES. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 187, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, G.E.; Smith, K.F. Summarizing the Evidence on the International Trade in Illegal Wildlife. Ecohealth 2010, 7, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, M.Y.; Choy, C.P.P.; Ip, Y.C.A.; Rao, M.; Huang, D. Diversity and origins of giant guitarfish and wedgefish products in Singapore. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanath, T.; Foster, S.J.; Ramkumar, B.; Vincent, A.J. A practical approach to meeting national obligations for sustainable trade under CITES. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, P.K.; Acharya, K.P.; Baral, H.S.; Heinen, J.T.; Jnawali, S.R. Trends, Patterns, and Networks of Illicit Wildlife Trade in Nepal: A National Synthesis. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Shigueto, J.; Alfaro-Cordova, E.; Mangel, J.C. Review of threats to the Pacific seahorse Hippocampus ingens (Girard 1858) in Peru. J. Fish Biol. 2022, 100, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Burkhart, E.P.; Chen, V.Y.J.; Wei, X. Promotion of in situ forest farmed American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) as a sustainable use strategy: Opportunities and challenges. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 652103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondhali, U.; Merzon, A.; Nunphong, T.; Lo, T.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Petrossian, G.A. Crime script analysis of the illegal sales of spiny-tailed lizards on YouTube. Crime Sci. 2024, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongol, Y.; Heinen, J.T. Pitfalls of CITES implementation in Nepal: A policy gap analysis. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, Ç.; Elvan, O.D. Legal analysis of the CITES convention in terms of Turkish administrative and judicial processes. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2024, 24, 515–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, P.K.; Khatiwadi, A.P.; Ghimirey, Y. Lens for Biodiversity Conservation in Nepal: Status, Challenges and the Way Forward; Society for Conservation Biology Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022; ISBN 978-9937-1-2430-0. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Nepal. National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2029; Nepal Gazette; Ministry of Law and Justice: Kathmandu, Nepal, 1973; Volume 23, pp. 1–27.

- Cites.org. Status of Legislative Progress for Implementing CITES (Updated November 2022). Available online: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/documents/legislation-status/legislation-status.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Wyatt, T. Is CITES Protecting Wildlife? Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 9780367440718. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, N.; Dhakal, K.; Saud, D.S. Checklist of CITES Listed Flora of Nepal, 1st ed.; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Department of Plant Resources: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017; ISBN 9789937029520.

- Bashyal, R.; Paudel, K.; Hinsley, A.; Phelps, J. Making Sense of Domestic Wildlife and CITES Legislation: The Example of Nepal’s Orchids. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 280, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Nepal’s Flora and Fauna in the Current CITES Lists 1995; IUCN Nepal Country Office: Kathmandu, Nepal, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, Y.; Chettri, N.; Dhakal, M.; Asselin, H.; Chand, R.; Chaudhary, R.P. Illegal wildlife trade is threatening conservation in the transboundary landscape of Western Himalaya. J. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 59, 125952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J.T.; Dahal, S. Research Priorities for the Conservation of Nepal’s Lesser Terrestrial Vertebrates. Asian J. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 12, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J.T.; Shrestha-Acharya, R. The non-timber forest products sector in Nepal: Emerging policy issues in plant conservation and utilization for sustainable development. J. Sustain. For. 2011, 6, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, K. Transboundary Biodiversity Conservation Initiative: An Example from Nepal. J. Sustain. For. 2003, 17, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, P.H. International Protection of Endangered Species in the Face of Wildlife Trade: Whither Conservation Diplomacy? Asia Pacific J. Environ. Law 2017, 20, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J.T.; Leisure, B. A New Look at the Himalayan Fur Trade. Oryx 1993, 27, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, B.R.; Wright, W.; Khatiwada, A.P. Illegal Hunting of Prey Species in the Northern Section of Bardia National Park, Nepal: Implications for Carnivore Conservation. Environments 2016, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmacharya, D.; Sherchan, A.M.; Dulal, S.; Manandhar, P.; Manandhar, S.; Joshi, J.; Bhattarai, S.; Bhatta, T.R.; Awasthi, N.; Sharma, A.N.; et al. Species, Sex and Geo-Location Identification of Seized Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) Parts in Nepal—A Molecular Forensic Approach. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.; Shrestha, M.B. The Illegal Trade in Otter Pelts in Nepal. TRAFFIC Bull. 2018, 30, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bashyal, A.; Shrestha, N.; Dhakal, A.; Khanal, S.N.; Shrestha, S. Illegal Trade in Pangolins in Nepal: Extent and Network. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 32, e01940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.G.; Rorres, C.; Joly, D.O.; Brownstein, J.S.; Boston, R.; Levy, M.Z.; Smith, G. Quantitative Methods of Identifying the Key Nodes in the Illegal Wildlife Trade Network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7948–7953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Dahal, B.R.; Chandra Aryal, P.; Sharma, B. Identification of illegal wildlife trade routes from Nepal. GoldenGate J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 4, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, L.; Bouhuys, J. Illegal Otter Trade in Southeast Asia; TRAFFIC: Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 2018; Available online: https://wilderness-society.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/seasia-otter-report.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Katuwal, H.B.; Neupane, K.R.; Adhikari, D.; Sharma, M.; Thapa, S. Pangolins in eastern Nepal: Trade and ethno-medical importance. J. Threat. Taxa 2015, 7, 7563–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, A.; Aguirre, A.A. Infectious Diseases and the Illegal Wildlife Trade. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1149, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, E.R.; Dale, E.; Aguirre, A.A. Illegal Wildlife Trade and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Pervasive Impacts to Species, Ecosystems and Human Health. Animals 2021, 11, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.E. The Black Market for Wildlife: Combating Transnational Organized Crime in the Illegal Wildlife Trade. Vand. J. Transnat’l L. 2003, 36, 1657. [Google Scholar]

- Milledge, S.A.H. Illegal Killing of African Rhinos and Horn Trade, 2000–2005: The Era of Resurgent Markets and Emerging Organized Crime. Pachyderm 2007, 43, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cites.org. Checklist of CITES Species. Available online: https://checklist.cites.org/#/en (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- DNPWC. Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora of Nepal listed in CITES Schedules; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2018. Available online: https://dnpwc.gov.np/media/publication/CITES_Book_DNPWC_2018.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- DNPWC; BCN. Birds of Nepal: An Official Checklist; Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Birds Conservation Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, T.P.; Adhikari, S.; Anton, P.G. An Updated Checklist of Amphibians and Reptiles of Nepal. ARCO-Nepal Newsl. 2022, 23, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNPWC. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2014–2020; Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2024.

- sawen.org. South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network Mission. Available online: https://www.sawen.org/page/mission (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Government of Nepal. The Control of International Trade of Endangered Wild Fauna and Flora Act, 2017; Nepal Gazette; Ministry of Law and Justice: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017; Volume 67, pp. 1–27.

- Jacobson, H.K.; Weiss, E.B. Strengthening Compliance with International Environmental Accords: Preliminary Observations from a Collaborative Project. Glob. Gov. 1995, 1, 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, N.; Heinen, J.T. Regulatory Compliance of Community-Based Conservation Organizations: Empirical Evidence from Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, K.N.; Heinen, J.T. Perceptions of, and Motivations for, Land Trust Conservation in Northern Michigan: An Analysis of Key Informant interviews. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Nepal. Regulations on the Control of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Regulations, 2019; Nepal Gazette; Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019; Volume 69, pp. 1–65.

- Government of Nepal. The Constitution of Nepal; Nepal Gazette: Kathmandu, Nepa, 2015; pp. 1–225. Available online: https://ag.gov.np/files/Constitution-of-Nepal_2072_Eng_www.moljpa.gov_.npDate-72_11_16.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Government of Nepal. dnpwc.gov.np/en/. Objectives. Available online: https://dnpwc.gov.np/en/objective/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Government of Nepal. dofsc.gov.np. Objectives. Available online: https://dofsc.gov.np/view-page/34 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Government of Nepal. dpr.gov.np. Work Description of Department of Forests and Soil Conservation. Available online: https://dpr.gov.np/हाम्रोबारे/परिचय// (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Government of Nepal. nhmnepal.edu.np. Museum Info. Available online: https://nhmnepal.edu.np/museum-info/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Kilonzo, N.; Heinen, J.T.; Byakagaba, P. An Assessment of the Implementation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in Kenya. Diversity 2024, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.; Feng, Y.P.; Hinsley, A.; Lee, T.M.; Possingham, H.P.; Smith, S.N.; Thomas-Walters, L.; Wang, Y.; Biggs, D. Understanding China’s Political Will for Sustainability and Conservation Gains. People Nat. 2023, 5, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, C. Good Governance and Strong Political Will: Are They Enough for Transformation? Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.E.; Ali, S.H. Environmental Diplomacy Negotiating More Effective Global Agreements, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-9397976. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, L.K. Beyond Environmental Diplomacy: The Changing Institutional Structure of International Cooperation. In International Environmental Diplomacy: The Management and Resolution of Transfrontier Environmental Problems; Carroll, J.E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 13–28. ISBN 978-0-521-33437-2. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Nepal. National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (Fifth Amendment) Act 1973; Nepal Gazette; Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017; Volume 66, pp. 1–16.

- Government of Nepal. Forest Act 2019; Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019; pp. 1–38.

- Per, E. Tropikal ormanlardan Türkiye’ye papağan ticaretinin durumu. Turk. J. For. Türkiye Orman. Derg. 2018, 19, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharma, K. The political economy of civil war in Nepal. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1237–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Heinen, J.T. Challenges in the conservation of an over-harvested plant species with high socioeconomic value. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Nepal. National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (Fifth Amendment) Regulations 2030; Nepal Gazette; Ministry of Law and Justice and Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019; Volume 66, pp. 1–54.

- Heinen, J.T.; Thapa, B.B. A feasibility study of a proposed trekking trail in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. J. For. Inst. 1990, 10, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Addison, P.F.E.; Carbone, G.; McCormichj, N. The Development and Use of Biodiversity Indicators in Business: An Overview; IUCN Business and Biodiversity Programme: Gland, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: www.iucn.org/resources/publications (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Garrison, J.L. Conventional in international trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora and eh debate over sustainable use. Pace Environ. Law Rev. 1994, 12, 301–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.J.; Morton, O.; Scfeffers, B.R.; Edwards, D.P. The ecological drivers and consequences of wildlife trade. Biol. Rev. 2022, 98, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayotou, T. Conservation of biodiversity and economic development: The concept of transferable development rights. Environ. Resour. Econ. 1994, 4, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SN | Chapter Number | Article Number | Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preamble | Introduction to the act. | |

| 2 | 1: Preliminary: | I | Short title, extension, and commencement |

| 3 | 1 | II | Definition |

| 4 | 2: Provisions concerning Transactions of Endangered wild fauna or flora or specimen thereof | III | Prohibition on trade or transaction of threatened or vulnerable wild fauna or flora or specimen thereof |

| 5 | 2 | IV | License to be requested |

| 6 | 2 | V | Advice to be required for granting license |

| 7 | 2 | VI | License granting provisions. |

| 8 | 2 | VII | Threatened species of wild fauna or flora or specimen |

| 9 | 2 | VIII | Transaction of protected wild fauna or flora |

| 10 | 2 | IX | Certificate of origin and export permission |

| 11 | 2 | X | Special provisions concerning re export |

| 12 | 2 | XI | No risks to the existence of fauna or flora |

| 13 | 2 | XII | To have become a state party to Convention |

| 14 | 3: Provisions concerning Registration of the Endangered wild fauna or flora or specimen thereof | XIII | Endangered species of wild fauna or flora to be registered |

| 15 | 3 | XIV | Imported endangered wild fauna or flora or specimen thereof to be registered |

| 16 | 3 | XV | Not to Transfer |

| 17 | 4: Provisions concerning Management Authority and Scientific Authority | XVI | Management Authority |

| 18 | 4 | XVII | Functions, Duties and Powers of Management Authority |

| 19 | 4 | XVIII | Scientific Authority |

| 20 | 4 | XIX | Functions, Duties and Powers of Scientific Authority |

| 21 | 5: Offences and Punishment | XX | Offences deemed to be committed |

| 22 | 5 | XXI | Punishment: |

| 23 | 5 | XXII | To be confiscated |

| 24 | 6: Investigation and Filing of Cases | XXIII | Investigation Officer |

| 25 | 6 | XXIV | Accused Person may be remanded to custody: |

| 26 | 6 | XXV | Filing of a Case |

| 27 | 6 | XXVI | Court to Try the Cases |

| 28 | 7: Miscellaneous Provisions | XXVII | Extraordinary Powers of Government of Nepal |

| 29 | 7 | XXVIII | Non-application when in transit |

| 30 | 7 | XXIX | Not to be deemed to be used for commercial use |

| 31 | 7 | XXX | Management of confiscated wild Fauna or Flora or their specimen |

| 32 | 7 | XXXI | Endangered Fauna or Flora National Coordination Committee |

| 33 | 7 | XXXII | Publication of Names of Wild Fauna and Flora |

| 34 | 7 | XXXIII | Records of details to be maintained |

| 35 | 7 | XXXIV | Fund may be created |

| 36 | 7 | XXXV | Awards may be granted |

| 37 | 7 | XXXVI | To be according to the laws in force |

| 38 | 7 | XXXVII | Rules may be formed |

| 39 | 7 | XXXVIII | Directives may be formulated |

| Act | Term | Prosecution | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| CITES ACT 2017 [56] | Appendix I (Threatened Wild Fauna and Flora) | An offender can be sentenced to 5 to 15 years in prison or a fine of five hundred thousand rupees to one million rupees or both. | Species listed in different Appendices of CITES are collectively termed “Endangered wild fauna and flora” |

| Appendix II (Vulnerable Wild Fauna and Flora) | Imprisonment of 2 to 10 years or fine from one hundred thousand rupees to five hundred thousand rupees or both for an offense against fauna and fine of fifty thousand to one hundred thousand rupees or imprisonment of six months to one year or both for an offense against flora. | ||

| Appendix III (Protected Wild Fauna and Flora) | Imprisonment of one to five years or with a fine of from twenty thousand rupees to one hundred thousand rupees or both for an offense against fauna and fine of one thousand to fifty thousand rupees or imprisonment of one month to six months or both for an offense against flora. | ||

| NPWC ACT 1973 (FIFTH AMENDMENT) (GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL, 2017A) [71] | Protected species (rhinoceros, tiger, elephant, musk deer, snow leopard) | Imprisonment of five to fifteen years or a fine of five hundred thousand to one million rupees or both in case of illegally poaching, injuring, buying, selling or providing rhinoceros, tiger, elephant, musk deer, clouded leopard, snow leopard, or bison as well as keeping, buying, selling or transporting musk pod of musk deer, skin of snow leopard and other protected species For other species, the punishment is imprisonment from one to ten years or a fine of forty to seventy thousand rupees or both, and person hunting, killing, or injuring species other than birds and fish inside protected areas is imprisonment of six months to two years or a fine of one thousand rupees to 10 thousand rupees or both. | All the species listed in the NPWC Act 1973 are termed “Schedule I Protected Species” |

| Other protected species | Except for the above-mentioned species hunting, killing, or injuring protected species, the punishment is fine of one hundred thousand rupees to five hundred thousand rupees or imprisonment of one year to ten years or both. | ||

| Species within protected areas | Except for birds and fish, hunting, killing, or injuring species within protected areas without a license is punishable by a fine of twenty thousand rupees to fifty thousand rupees or imprisonment of six months to one year or both. | ||

| Protected birds | Killing, hunting or injuring protected species of birds is punishable by fifteen thousand to thirty thousand rupees or imprisonment of three months to nine months or both. | ||

| Other species of birds inside protected areas | Hunting, killing, or injuring bird species except that in protected lists without a license is punishable by twenty thousand to fifty thousand rupees or imprisonment of six months to one year or both. | ||

| Building inside protected areas | Building any kind of house, hut, lodging place, or infrastructure or using resources inside national parks and reserves is punishable by twenty thousand to fifty thousand rupees or imprisonment for one year or both. | ||

| Removing vegetation, mining, or harming land and wildlife inside protected areas | Removing trees, shrubs, or any kind of vegetation, drying, firing, destroying or transporting vegetation, mining, stone removing, minerals extracting, or soil collection, as well as harming wildlife and land inside the national parks and reserve, is punishable by compensating if the loss is up to one thousand rupees, compensating and imprisonment upto six months or both if the loss is one thousand to ten thousand rupees, or compensating double and imprisonment of one year or both if the loss is more than ten thousand rupees. | ||

| Breeding or rearing wildlife or running a zoo without permission | Rearing, breeding, or running a zoo without a license is punishable by six months of imprisonment, or fifty thousand rupees fine, or both. | ||

| Punishment to the accomplice | An accomplice in any offense described by this act is punishable by half the punishment given to the offender. However, in the case of offense to rhinoceros, tiger, musk deer, and elephant, the accomplice is punished same as the offender. | ||

| Right to seize | An officer has the right to seize any wildlife contraband, arms, vehicle, or other equipment utilized in the offense conducted against the rules made in this act. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dahal, S.; Heinen, J.T. A History of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Implementation in Nepal. Diversity 2025, 17, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17050312

Dahal S, Heinen JT. A History of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Implementation in Nepal. Diversity. 2025; 17(5):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17050312

Chicago/Turabian StyleDahal, Sagar, and Joel T. Heinen. 2025. "A History of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Implementation in Nepal" Diversity 17, no. 5: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17050312

APA StyleDahal, S., & Heinen, J. T. (2025). A History of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Implementation in Nepal. Diversity, 17(5), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17050312