The Swedish Fauna of Freshwater Snails—An Overview of Zoogeography and Habitat Selection with Special Attention to Red-Listed Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. The Geographical Area and Its Freshwater Habitats

2.2. The Exploration of the Swedish Freshwater Snail Fauna

2.3. Compilation of the Investigated Material

2.4. Taxonomic, Nomenclatural and Determination Problems

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Taxonomic Overview

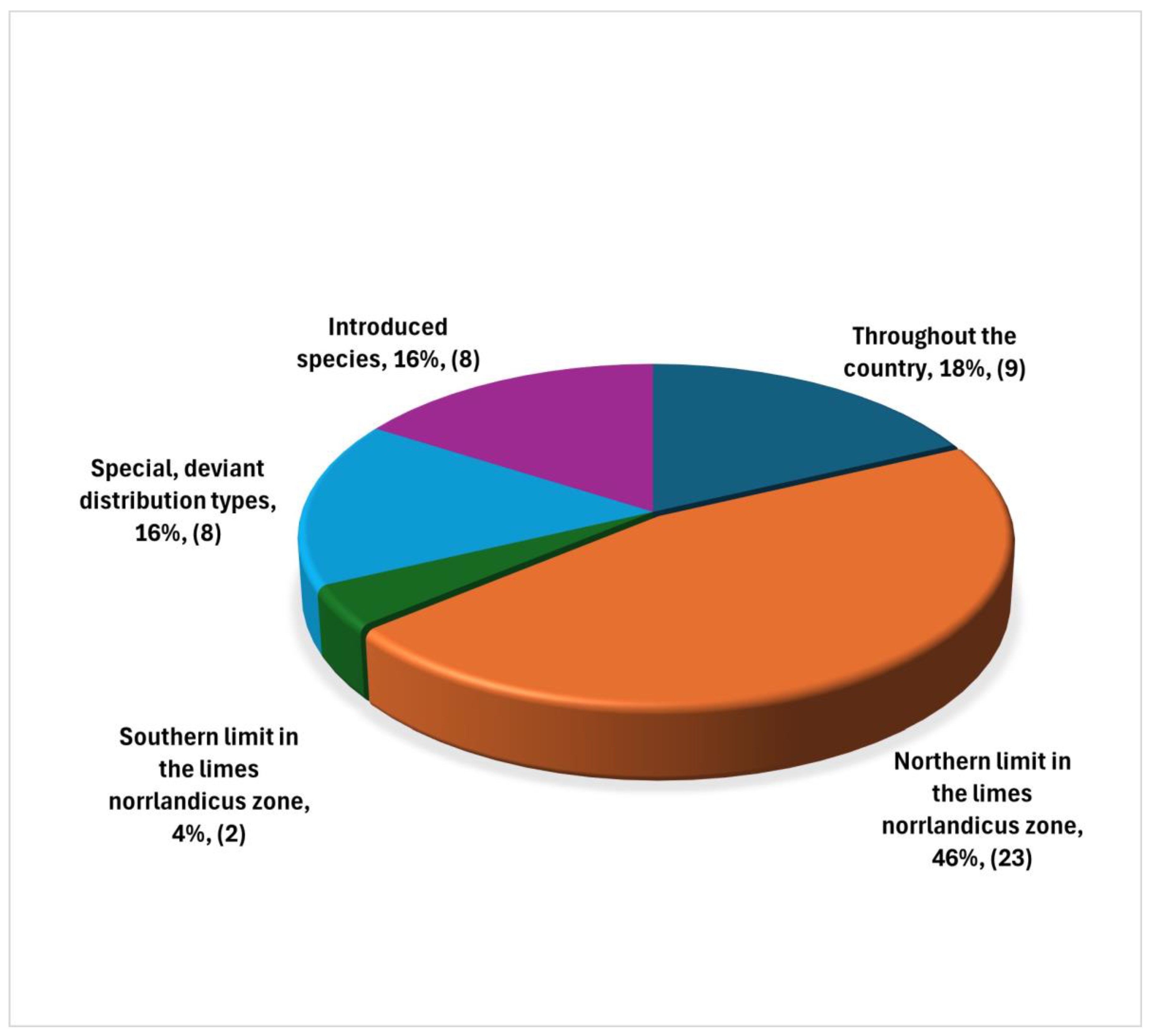

3.2. Zoogeographical Overview

| Species | Remarks | Habitat | Red List Sweden | Red List Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valvata piscinalis (O. F. Müller, 1774) | Lakes and slowly flowing waters. Also in brackish waters. (A) | LC | LC | |

| Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Rare in an approximately 10 km wide zone along the west coast. | Lakes, smaller water bodies and slowly flowing waters. Also in brackish waters (B) | LC | LC |

| Galba truncatula (O. F. Müller, 1774) | Host species of Fasciola hepatica (Linnaeus, 1758). | Prefers smaller waters, ponds and ditches. Amphibious. Also in wet meadows and fens. (D) | LC | LC |

| Stagnicola palustris (O. F. Müller, 1774) | Details in distribution and ecology are partly unclear due to previous unclear taxonomy. | Shore zones of lakes, small water bodies and slow-running parts of watercourses. Also in brackish waters. (B) | LC | LC |

| Stagnicola fuscus (C. Pfeiffer, 1821) | Details in distribution and ecology are partly unclear due to previous unclear taxonomy. | Shore zones of lakes, small water bodies and slow-running parts of watercourses. Also in temporary waters. (B) | LC | LC |

| Ampullaceana balthica (Linnaeus, 1758) | All kinds of freshwaters. Also in brackish waters. Most common freshwater snail in Sweden. (A) | LC | LC | |

| Peregriana labiata (Rossmässler, 1835) | Details in distribution and ecology are partly unclear due to previous unclear taxonomy. | Oligo-mesotrophic smaller lakes and tarns and forest and fen ponds. (D) | LC | LC |

| Bathyomphalus contortus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Lakes, ponds and watercourses. Also in brackish waters. (A) | LC | LC | |

| Gyraulus laevis (Alder, 1838) | Extremely rare. See taxonomical remarks. | Lakes, smaller waters and slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (B) | NT | LC |

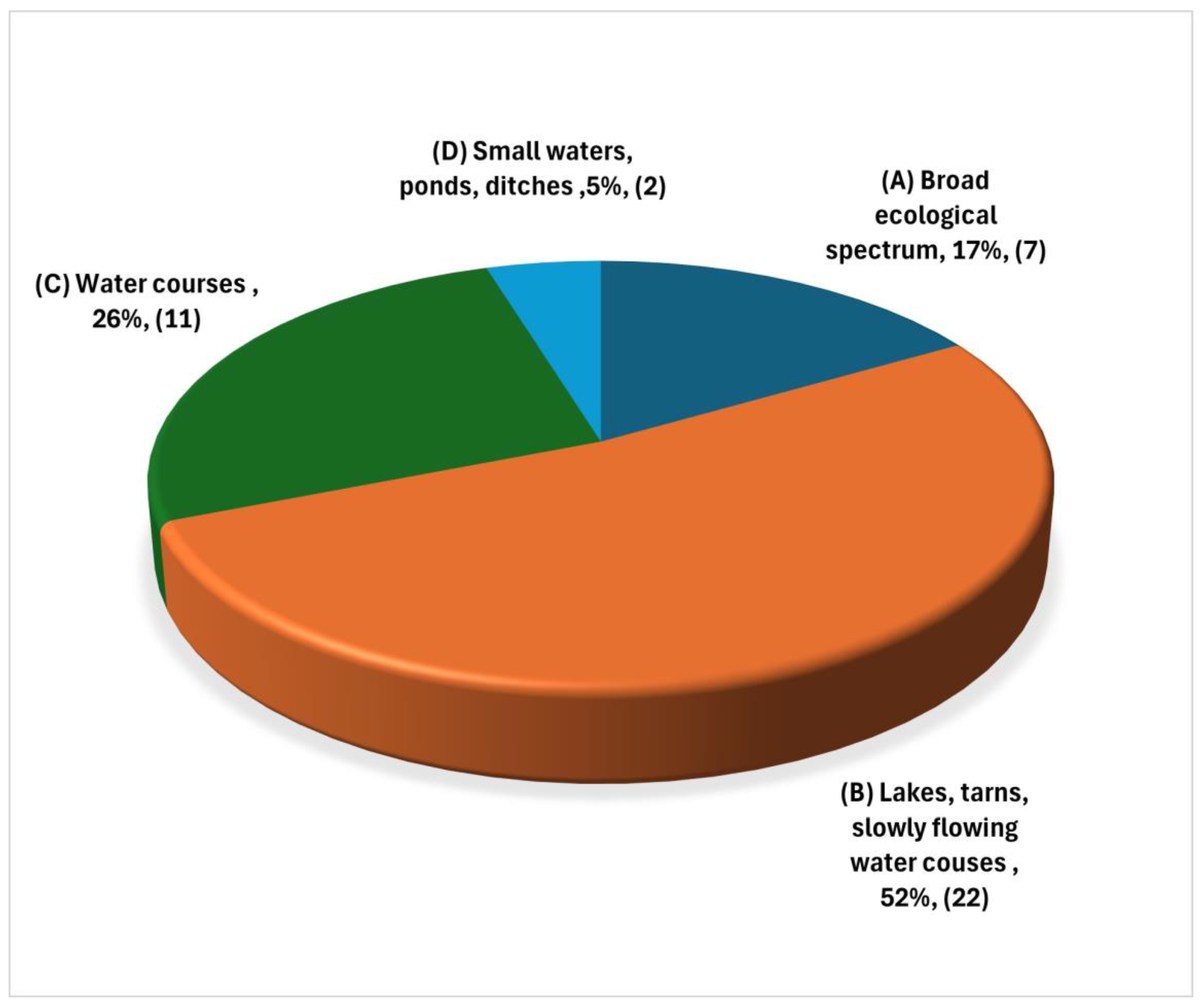

3.3. Habitat Selection and Salinity Tolerance

3.4. Red-Listed Species, Threats and Conservation

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lydeyard, C.; Cummings, K.S. (Eds.) Freshwater Mollusks of the World. A Distribution Atlas; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boycott, A.E. The Habitats of Fresh-Water Mollusca in Britain. J. Anim. Ecol. 1936, 5, 116–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frömming, E. Biologie der Mitteleuropäischen Süsswasserschnecken; Duncker & Humblot: Berlin, Germany, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Hubendick, B. Factors conditioning the Habitat of Freshwater snails. Bull. World Health Organ. 1958, 18, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Økland, J. Lakes and Snails. Environment and Gastropoda in 1500 Norwegian Lakes, Ponds and Rivers; Universal Book Services/Dr. W. Backhuys: Oestgeest, The Netherlands, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, R.T., Jr. The Ecology of Freshwater Molluscs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, E.E.; Gargominy, O.; Ponder, F.W.; Bouchet, P. Global diversity of gastropods (Gastropoda; Mollusca) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, E.; Neubauer, T.A.; Harzhauser, M.; Kroh, A.; Mandic, O. Distribution patterns of Europaean lacustrine gastropodes; a result of environmental factors and deglaciation history. Hydrobiologia 2016, 775, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Quintero, J.C. Latitudinal gradients of freshwater gastropods from the Western Palearctics. Aquar. Sci. 2025, 77, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.S. Freshwater Snails of Africa and Their Medical Importance, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kappes, H.; Haase, P. Slow, but steady: Dispersal of freshwater molluscs. Aquat. Sci. 2012, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilton, D.T.; Freeland, J.R.; Okamura, B. Dispersal in freshwater invertebrates. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Proschwitz, T. Amerikansk blåssnäcka—Fripassagerare på stavformad vattenskorpion. Fauna Flora 2009, 104, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kew, H.W. The Dispersal of Shells. An Inquiry into the Means of Dispersal possessed by Fresh-water and Land Mollusca. International Scientific Series 75; Paul, Trench & Trübner: London, UK, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, B.B.; Das, N.K.; Jadhav, A.; Roy, A.; Aravind, N.A. Global freshwater mollusc invasion: Pathways, potential distribution, and niche shift. Hydrobiologia 2023, 852, 1431–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Lima, M.; Lopes-Lima, A.; Burlakova, L.; Douda, K.; Alonzo, Á.; Karatayev, A.; Ng, T.H.; Vinarski, M.; Ziertz, A.; Sousa, R. Non-native freshwater molluscs: A brief global review of species, pathways, impacts and management strategies. Hydrobiologia 2025, 852, 1005–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, Á.; Collado, G.A.; Gérard, C.; Levri, E.P.; Salvador, R.B.; Castro-Diez, P. Effects of the invasive aquatic snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1853) on ecosystem properties and services. Hydrobiologia 2025, 852, 1339–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttelod, A.; Seddon, M.; Neubert, E. European Red List of Non-Marine Molluscs; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/rl-4-014.pdf. (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Böhm, M.; Dewhurst-Richman, N.I.; Seddon, M.; Ledger, S.E.H.; Albrecht, C.; Allen, D.; Bogan, A.E.; Cordeiro, J.; Cummings, K.S.; Cuttelod, A.; et al. The conservation status of the world’s freshwater molluscs. Hydrobiologia 2020, 848, 3231–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöer, P. The Freshwater Gastropodes of the West-Palearctic; I. Fresh- and brackish waters except spring and subterranean snails; II. Moitesieridae, Bythinellidae, Stenothyridae; III. Hydrobiidae Published by the author/S. Muchow, Neustadt, Holstein, Germany, 2019–2022; Biodiversity Research Lab: Hetlingen, Germany.

- SLU Artdatabanken (Ed.) Rödlistade arter i Sverige 2020; SLU Uppsala: Uppsala, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Selander, S. Det levande Landskapet i Sverige, 3rd ed.; Bokskogen Förlag: Gothenburg, Sweden, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Naturhistorisk Regionindelning av Norden, 2nd ed.; Liber Distribution: Stockholm, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- SMHI. Available online: https://www.smhi.se/data/meteorologi/kartor/normal/arsmedeltemperatur-normal (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Fries, M. Limes norrlandicus-studier, en växtgeografisk gränsfråga historiskt belyst och exemplifierad. Sven. Bot. Tidskr. 1948, 43, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hård af Segerstad, F. Pflanzengeographische Studien im nordwestlichen Teil der Eichenregion Schwedens, I und II. Ark. Bot. 1935, 27, 1–405. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T.; Wengström, N. Zoogeography, ecology, and conservation status of the large freshwater mussels in Sweden. Hydrobiologia 2020, 848, 2869–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrikson, L.; Hindar, A.; Abrahamson, I. Restoring Acidified Lakes: An Overview. In The Lakes Handbook: Lake Restoration and Rehabilitation; O’Sullivan, P.E., Reynolds, C.S., Eds.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturae per Regna tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus, I. Editio Decima Reformata; Laurentius Salvius: Holmiae, Sweden, 1758. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund, C.A. Fauna Molluscorum Terrestrium et Fluviatilum Sveciae, Norvegiae et Daniae. 2 [Freshwater Molluscs]; A. Bonnier: Stockholm, Sweden, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund, C.A. Sveriges, Norges, Danmarks och Finlands land- Och Sötvatten-Mollusker. Excursionsfauna; Central-Tryckeriet: Stockholm, Sweden, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund, C.A. Sveriges, Norges, Danmarks och Finlands land- Och Sötvatten-Mollusker. Excursionsfauna. [Addition 1904]; A. Bonnier: Stockholm, Sweden, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, R.A.; von Proschwitz, T. The Swedish malacologist Carl Agardh Westerlund (1831–1908) a catalogue of his genus-group names and a bibliography of his malacological publications. Basteria 2021, 85, 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. In Memoriam Bengt Hubendick, 1916–2012. Fauna Flora 2012, 107, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hubendick, B. Recent Lymnaeidae. Their Variation, Morphology, Taxonomy, Nomenclature and Distribution; Almqvist & Wiksell: Stockholm, Sweden, 1951; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vinarski, M.V.; Vázquez, A.A. (Eds.) The Lymnaeidae—A Handbook on Their Natural History and Parasitological Significance; Zoological Monographs 7; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubendick, B. Die Verbreitungsverhältnisse der limnischen Gastropoden in Südschweden. Zool. Bidr. Upps. 1947, 24, 419–559. [Google Scholar]

- Hubendick, B. Våra snäckor i sött och bräckt vatten. In Illustrerad Handbok; A. Bonnier: Stockholm, Sweden, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Svenska sötvattensmollusker (snäckor och musslor)—En uppdaterad checklista med vetenskapliga och svenska namn. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2001, 2001, 37–47, [With English summary: Swedish Freshwater Mollusca: An up-dated Check-List with scientific and common names for all species.]. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T.; Roth, J.; Lundin, K.; Back, R. Nationalnyckeln till Sveriges Flora och Fauna. Blötdjur: Snyltsnäckor-Skivsnäckor. Mollusca: Pyramidellidae-Planorbidae; SLU Artdatabanken: Uppsala, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Degerman, E.; Fernholm, B.; Lingdell, P.-E. Bottenfauna och fisk i sjöar och vattendrag; Rapport 4345; Utbredning i Sverige Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, C.; Ericsson, U.; Medin, M.; Sundberg, I. Sötvattenssnäckor i Södra Sverige—En Jämförelse Med 1940-Talet; Rapport 4903; Naturvårdsverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schäffer, M.; Hausdorf, B. An Integrative Analysis of the Specific Distinctness of Valvata (Cincinna) ambigua Westerlund, 1873 and Valvata (Cincinna) piscinalis (Müller, 1774) (Gastropoda: Valvatidae). Diversity 2024, 16, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniebs, K.; Glöer, P.; Vinarski, M.V.; Hundsdoerfer, A.K. Intraspecific morphological and genetic variation in Radix balthica (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda; Basommatophora; Lymnaeidae) with morphological comparison to other European Radix species. J. Conchol. 2011, 40, 657–678. [Google Scholar]

- Schniebs, K.; Glöer, P.; Vinarski, M.V.; Hundsdoerfer, A.K. Intraspecific morphological and genetic variation in the European freshwater snail Radix labiata (Rossmaessler, 1835) (Gastropoda; Basommatophora; Lymnaeidae). Contrib. Zool. 2013, 82, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Glöer, P.; Vinarski, M.V. Taxonomical notes on Euro-Sibirian freshwater molluscs: 2. Redescription of Planorbis (Gyraulus) stroemi Westerlund, 1881 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Planorbidae). J. Conchol. 2009, 39, 717–725. [Google Scholar]

- Lorencová, E.; Beran, L.; Nováková, M.; Horsaková, V.; Rowson, B.; Havláč, Č.H.; Nekola, J.C.; Horsák, M. Invasion at the population level: A story of the freshwater snails Gyraulus parvus and G. laevis. Hydrobiologia 2021, 84, 4661–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C.D.; Vega, R.; Rahman, F.; Hornsburg, G.J.; Dawson, D.A.; Harvey, C.D. Population genetics and geometric morphometrics of the freshwater snail Segementina nitida reveal cryptic sympatric species of conservation value in Europe. Conserv. Genet. 2021, 22, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistical news from the Göteborg Natural History Museum 2010—Snails, slugs and mussels—With some notes on Gyraulus stroemi (Westerlund)—A freshwater snail species new to Sweden. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2011, 2011, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T.; Lingdell, P.-E.; Engblom, E. Distribution and ecology of Valvata sibirica Middendorff in Sweden. In Proceedings of the Abstractband, Symposium: Ökologie und Taxonomie von Süßwassermollusken, International Congress on Palaearctic Mollusca, Salzburg, Austria, 21–22 Februar 1997; Patzner, R.A., Müller, D., Rathmayr, U., Kornushin, A.V., Eds.; Institute für Zoologie, Universität Salzburg: Salzburg, Österreich, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Valvatoidea. In Nationalnyckeln Till Sveriges Flora och Fauna. Blötdjur: Sidopalpssnäckor-Taggsäcksnäckor. Mollusca: Cimidae-Asperspinidae; Lundin, K., Malmberg, K., Plejel, F., Eds.; SLU, Artdatabanken: Uppsala, Sweden, 2020; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Rödlistade sötvattensmollusker i Sverige—Utbredning, levnadssätt och status: I. Smal dammsnäcka. [Omphiscola glabra (O. F. Müller)]. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 1997, 1997, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistical news from the Göteborg Natural History Museum 2023—Land- and freshwater snails and slugs. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2024, 2024, 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistiskt nytt 2005—Snäckor, sniglar och musslor samt något om östlig snytesnäcka Bithynia transsilvanica (E. A. Bielz)—Återfunnen i Sverige och något om kinesisk dammussla Sinanodonta woodiana (Lea)—En för Sverige ny sötvattensmussla. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2006, 2006, 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistical news from the Göteborg Natural History Museum 2008—Snails, slugs and mussels—With some notes on the slug Limacus flavus (Linnaeus)—Refound in Sweden, and Balea heydeni von Maltzan—A land snail species new to Sweden. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2009, 2009, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zettler, M.L.; Jueg, U.; Menzel-Harloff, H.; Göllnitz, U.; Petrick, S.; Weber, E.; Seemann, R. Die Land-Und Süßwassermollusken Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns; Obotritendruck: Schwerin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Økland, J.; Økland, K.A. Innsjøer og dammer i Norge—Hva må vi gjøre for å beskytte virvelløse dyr. Fauna 1992, 45, 124–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hubendick, B. The Effectiveness of passive Dispersal in Hydrobia jenkinsi. Zool. Bidr. Från Upps. 1950, 28, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Artportalen. Available online: https://www.artportalen.se/ViewSighting/ViewSightingAsMap (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- von Proschwitz, T. Ekoparkens land och Sötvattensmollusker. Nyundersökningar, Sammanställning av Olika Inventerings-och Museimaterial Samt Utvärdering; Mimeographed Report; Göteborgs Naturhistoriska Museum: Gothenburg, Sweden, 1995; 58. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistiskt nytt 2004—Snäckor, sniglar och musslor inklusive något om kinesisk skivsnäcka Gyraulus chinensis (Dunker) och amerikansk tropiksylsnäcka Subulina octona (Brugière)—Två för Sverige nya, människospridda snäckarter. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2005, 2005, 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Odhner, N. Physa acuta, en i spridning stadd sötvattenssnäcka. Fauna Flora 1911, 6, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistiskt nytt 1999—Snäckor, sniglar och musslor. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2020, 2020, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Falkner, G.; von Proschwitz, T. A record of Ferrissia (Pettancylus) clessiniana (Jickeli) in Sweden, with remarks on the identity and distribution of the European Ferrissia species. J. Conchol. 1998, 36, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björck, S. The late Quaternary development of the Baltic Sea basin. In Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin; The BACC Author Team, Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 398–407. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeckel, S.G.A. Ergänzungen und Berichtigungen zum rezenten und quartären Vorkommen der mitteleuropäischen Mollusken. In Die Tierwelt Mitteleuropas 2; Brohmer, P., Ehrmann, P., Ulmer, G., Eds.; Quelle & Meyer: Leipzig, Germany, 1962; pp. 25–294. [Google Scholar]

- von Proschwitz, T. Faunistical news from the Göteborg Natural History Museum 2020—Land and freshwater snails, slugs, and mussels, with some notes on Krynickillus melanocephalus Kaleniczenko, 1851 a new invasive slug species spreading rapidly in Sweden. Göteborgs Nat. Hist. Mus. Årstr. 2021, 2021, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bjelke, U.; Ljungberg, H.; Sandström, J.; Andrén, B.; Brodin, Y.; Coulianos, C.-C.; Gullefors, B.; Hobro, R.; Lundberg, S.; von Proschwitz, T.; et al. Limniska evertebrater. In Tillstånd och Trender för Arter Och Deras Livsmiljöer—Rödlistade Arter i Sverige 2020; Wenche, E., Ahrné, K., Bjelke, U., Nordström, S., Ottosson, E., Sandström, S., Eds.; SLU Artdatabanken Rapporterar: Uppsala, Sweden, 2020; Volume 24, p. 64. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Indigenous | Introduced | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valavatoidea | 4 | - | 4 |

| Hygrophila | 31 | 6 | 37 |

| Neriotomorpha | 1 | - | 1 |

| Caenogastropoda | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Total | 42 | 8 | 50 |

| Species | Remarks | Habitat | Red List Sweden | Red List Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marstoniopsis insubrica (Küster, 1853) | Shore zones of lakes, in the space between stones. (B) | LC | LC | |

| Bithynia tentaculata (Linnaeus, 1758) | Extension further northwards along the coastal area of the Bothnian Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia. | Lakes and ponds of eutrophic character, slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (A) | LC | LC |

| Bithynia leachii (Sheppard, 1823) | Vegetation-rich lakes and ponds of eutrophic character, slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (B) | LC | LC | |

| Valvata cristata O. F. Müller, 1774 | Extension further northwards along the coastal area of the Baltic Sea into the province of Jämtland. | Vegetation-rich lakes and ponds with soft bottoms. (B) | LC | LC |

| Valvata macrostoma Mörch, 1864 | Extremely rare. A few isolated localities further northwards. | Smaller water bodies and ponds with rich vegetation, temporal ponds in woods. (D) | NT | NT |

| Stagnicola corvus (Gmelin, 1791) | Details in distribution and ecology are partly unclear due to previous unclear taxonomy. | Naturally eutrophic, vegetation-rich ponds and shore zones of lakes, also in slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (B) | LC | LC |

| Myxas glutinosa (O. F. Müller, 1774) | Extension further northwards along the coastal area of the Bothnian Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia. | Lakes, with hard water, mainly on hard bottoms. Also in brackish waters. (B) | LC | LC |

| Radix auricularia (Linnaeus, 1758) | Extension further northwards along the coastal area of the Bothnian Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia. | Naturally eutrophic lakes and ponds with hard water. Also in brackish waters. (B) | LC | LC |

| Ampullaceana ampla (W. Hartmann, 1821) | Details in distribution and ecology are partly unclear due to previous unclear taxonomy. | Naturally eutrophic and vegetation-rich lakes and ponds. (D) | LC | LC |

| Acroloxus lacustris (Linnaeus, 1758) | Natural eutrophic, vegetation-rich ponds, also in slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (D) | LC | LC | |

| Physa fontinalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | A few isolated localities further northwards. | Vegetation-rich ponds and shore zones of lakes, also in slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (A) | LC | LC |

| Aplexa hypnorum (Linnaeus, 1758) | Rare. A few isolated localities further northwards. | Ponds (also of temporary character), stagnant water between tussocks in fens. (D) | LC | LC |

| Planorbis planorbis (Linnaeus, 1758) | A few isolated localities further northwards. | Vegetation-rich ponds and shore zones of lakes, also in slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (A) | LC | LC |

| Planorbis carinatus O. F. Müller, 1774 | Rare in the west. | Natural eutrophic, vegetation-rich ponds, also in slowly flowing parts of watercourses (B). | LC | LC |

| Anisus leucostoma (Millet, 1813) | Ponds (also of temporary character), ditches, oxbow lakes. (D) | LC | LC | |

| Anisus vortex (Linnaeus, 1758) | A few isolated localities further northwards. | Vegetation-rich ponds and shore zones of lakes, also in slowly flowing parts of smaller watercourses and ditches. (B) | LC | LC |

| Gyralus crista (Linnaeus, 1758) | Extension further northwards along the coastal area of the Baltic Sea and the Sea of Bothnia and westwards into the province of Jämtland. | Vegetation-rich, eutrophic ponds and ditches, also in shore zones of lakes. Also in brackish waters. (D) | LC | LC |

| Gyraulus albus (O. F. Müller, 1774) | A few isolated localities further northwards. | All kinds of freshwaters. Also in brackish waters. (A) | LC | LC |

| Gyraulus riparius (Westerlund, 1865) | Also in an isolated locality further northwards (in the province of Medelpad). | Shore zone of naturally meso-eutrophic lakes. (B) | LC | LC |

| Ancylus fluviatilis O. F. Müller, 1774 | A few isolated localities further northwards. | Streaming, well-oxygenated watercourses with hard bottoms of rocks and stones, also in rocky, wave-exposed shores of big lakes. (C) | LC | LC |

| Planorbarius corneus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eastern, introduced in a few localities in the west. | Natural eutrophic, vegetation-rich ponds and lakes, also in slowly flowing parts of watercourses. (B) | LC | LC |

| Segmentina cf. clausulata (J. Férussac, 1807) | See taxonomic remarks. | Natural eutrophic, vegetation-rich ponds, also in slowly flowing parts of smaller watercourses. (D) | LC | Not rated. |

| Hippeutis complanatus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Natural meso-eutrophic, vegetation-rich ponds, also in slowly flowing parts of smaller watercourses. (B) | LC | LC |

| Species | Remarks | Habitat | Red List Sweden | Red List Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gyraulus acronicus (A. Férussac, 1807) | Occurs also in the inlands of the south. | Lakes and tarns of oligo-mesotrophic character, also in large-middle-sized watercourses. (B) | LC | DD |

| Gyraulus stromi (Westerlund, 1881) | Details in distribution are unclear due to confusion with G. acronicus. | Lakes and tarns of oligo-mesotrophic character, also in large-middle-sized watercourses. (B) | LC | Not rated |

| Species | Remarks | Habitat | Red List Sweden | Red List Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theodoxus fluviatilis (Linnaeus, 1758) | Southern-eastern Sweden, with an extension northward in the coastal area of the Baltic Sea, the Sea of Bothnia and the Gulf of Bothnia. | Lakes and watercourses with hard bottoms. Also in brackish waters. (B) | LC | LC |

| Viviparus viviparus (Linnaeus, 1758) | Eastern Middle Sweden. | Vegetation-rich shore zones of lakes and watercourses. Also in brackish waters. (B) | LC | LC |

| Viviparus contectus (Millet, 1813) | Southern Sweden. | Vegetation-rich shore zones of lakes and watercourses. (B) | LC | LC |

| Bithynia transsilvanica (Bilelz, 1853) | Extremely rare, two localities in middle Sweden. | Vegetation-rich, slowly flowing watercourses. (C) | VU | VU |

| Valvata sibirica Middendorff, 1851 | Inland of northernmost Sweden. | Shallow, vegetation-rich lakes and tarns, oxbow lakes, also in slowly flowing watercourses. (B) | NT | Not rated |

| Omphicsola glabra (O. F. Müller, 1774) | Pronounced western-suboceanic with markedly decreasing frequency eastwards. | Small ponds, woodland puddles, often of temporary character, ditches and slow-flowing smaller watercourses. (D) | NT | NT |

| Anisus vorticulus (Trochel, 1834) | Extremely rare, only found in the southernmost part (Skåne). Possibly extinct. | Ponds, ditches and slow-flowing watercourses, also in vegetation-rich shore zones of lakes. (D) | DD | NT |

| Segmentina nitida (O. F. Müller, 1774) s.s. | Extremely rare, only found in the southernmost part (Skåne). Earlier not separated from S. cf. clausulata (cf. above). | Naturally eutrophic, vegetation-rich shore zones of lakes and watercourses. (B) | LC (but not rated s.s). Suggested VU. | Not rated (s.s). |

| Species | First Record | Habitat |

|---|---|---|

| Melanoides tuberculata (O. F. Müller, 1774) | 1982 | Only artificially heated waters. |

| Potamopyrgus antipodarum (J. E. Gray, 1843) | 1920s [58] | Established and spread. Fresh and brackish waters. |

| Pseudosuccinea columella (Say, 1817) | 1943 [60,61] | Only artificially heated waters. |

| Physella acuta (Draparnaud, 1805) | 1895 [61,62] | Established outdoors. |

| Gyraulus parvus (Say, 1817) | 1999 [63] | Established outdoors. See taxonomical remarks. |

| Gyraulus chinensis (Dunker, 1848) | 2001 [61] | Only artificially heated waters. |

| Ferrissia californica B. Walker, 1903 | 1943 [64] | Established outdoors. |

| Planorbella duryi (Wetherby, 1879) | 1994 [60] | Only artificially heated waters. |

| Species | Limit Salinity Tolerance ‰ |

|---|---|

| Myxas glutinosa (O. F. Müller, 1774) | <3 [66] |

| Gyraulus albus (O. F. Müller, 1774) | <3 ([66], personal observation) |

| Gyralus crista (Linnaeus, 1758) | <3 [66] |

| Valvata piscinalis (O. F. Müller, 1774) | <4 [66] |

| Radix auricularia (Linnaeus, 1758) | <6 ([66], personal observation) |

| Bathyomphalus contortus (Linnaeus, 1758) | <6 [66] |

| Viviparus viviparus (Linnaeus, 1758) | <6 [59,66] |

| Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | <7 [66] |

| Stagnicola palustris (O. F. Müller, 1774) | <8 [66] |

| Ampullaceana balthica (Linnaeus, 1758) | <14 ([66], personal observation) |

| Potamopyrgus antipodarum (J. E. Gray, 1843) | <17 [66] |

| Theodoxus fluviatilis (Linnaeus, 1758) | <19 ([66], personal observation) |

| Species | Red List Category Swedish National Level | Red List Category European Level |

|---|---|---|

| Bithynia transsilvanica (Bilelz, 1853) | VU | LC |

| Valvata sibirica Middendorff, 1851 | NT | Not rated |

| Valvata macrostoma Mörch, 1864 | NT | NT |

| Omphiscola glabra (O. F. Müller, 1774) | NT | NT |

| Gyraulus laevis (Rossmässler, 1835) | NT | LC |

| Anisus vorticulus (Trochel, 1834) | DD | NT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Proschwitz, T. The Swedish Fauna of Freshwater Snails—An Overview of Zoogeography and Habitat Selection with Special Attention to Red-Listed Species. Diversity 2025, 17, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17040251

von Proschwitz T. The Swedish Fauna of Freshwater Snails—An Overview of Zoogeography and Habitat Selection with Special Attention to Red-Listed Species. Diversity. 2025; 17(4):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17040251

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Proschwitz, Ted. 2025. "The Swedish Fauna of Freshwater Snails—An Overview of Zoogeography and Habitat Selection with Special Attention to Red-Listed Species" Diversity 17, no. 4: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17040251

APA Stylevon Proschwitz, T. (2025). The Swedish Fauna of Freshwater Snails—An Overview of Zoogeography and Habitat Selection with Special Attention to Red-Listed Species. Diversity, 17(4), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17040251