1. Introduction

Reproductive interactions (e.g., courtship and copulation) between members of different species have been observed in several taxa [

1,

2]. Their potential evolutionary consequences depend on the sign and magnitude of their effects on the fitness of the interacting species. In some cases, the effects could be negligible, for example when the interactions occur very rarely. In other cases, one of the species is selected to induce these interactions against the interests of the other species, as is the case of predatory female

Photuris fireflies that respond to the mating signals of the males of their firefly prey species to attract them and feed on them. When these interactions have a negative fitness effect on one or more of the interacting species, the interaction is called reproductive interference [

1,

2]. Reproductive interference is a potentially powerful selective pressure that can affect the evolution of mating signals and genitalia and promote isolation mechanisms, but it could also result in hybridization [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Stanger-Hall and Lloyd [

6] performed a phylogeny-controlled comparative study of the mating signals of 34 North American

Photinus firefly species, finding that reproductive character displacement explained male flash duration divergence among sympatric species and suggesting that reproductive interference has been an important selective pressure in this insect group. However, we were not able to find published reports of naturally occurring interspecific sexual interactions between firefly species other than those induced by the aggressive mimicry of the predatory

Photuris spp. females [

7].

The existence of synchronous fireflies is an intriguing problem for scientists [

8,

9,

10] and a fascinating phenomenon for non-scientists [

11,

12]. This magnificent spectacle is produced by thousands of mostly male fireflies signaling synchronously to prospective mates during a relatively short period of time every night. Why these fireflies congregate in such large numbers and why they synchronize their luminous signals is not understood for any particular species, although there are hypotheses on the mechanisms responsible for the synchronization and on the potential reproductive advantages, e.g., [

7,

8,

10]. Evidence indicates that the operational sex ratio (OSR: the number of sexually receptive females divided by the number of sexually active males) is male-biased in synchronous fireflies of North America and Asia, and this kind of bias is known to produce strong competition for mates between males [

13,

14]. This bias is present in synchronous fireflies of North America and Asia despite their behavioral differences: in North America, males mostly signal in flight while females remain perched, while in most (but not all [

8]) Asian species, the males signal while perching on trees where females are also perched but do not participate in the synchronous flashing. We are aware of direct measurements of OSRs for only three synchronic species from Asia, and the values observed in each species were 60%, 70% and 74% of males in mating “congregations” (data summarized in [

8]). Direct evidence of strong competition for females, most likely resulting from a male-biased OSR, is the formation of “mating clusters”, groups consisting of one female and two or more courting males [

15]. In these clusters, the males walk or fly very close to the female, frequently sending signals, and in many cases, they are in physical contact with the female and with each other. Copeland et al.’s [

16] description of male behavior in clusters of the synchronous

P. carolinus clearly indicates the competitive character of this behavior: “males…vigorously mount each other or the courting female or both. Piles of grappling males formed and engaged in extensive grappling, walking, attempted coupling”. Faust [

9], p. 216 also mentions that “Direct interference competition among males appears intense in

P. carolinus, and the mating clusters described [for this species] are similar to…[the] “love knots” described in

P. pyralis” (

P. pyralis is considered a synchronic species by Copeland et al. [

16]). Copeland et al. [

16], p. 20, also mention that mating males in “stage I” (this stage is when the male, at the beginning of copulation, is on top of and looking in the same direction as the female; stage II is when the copulating pair is in the tail-to-tail position, looking in more or less opposite directions) can be displaced by other males. Copeland et al. [

16], p. 111 say that cluster formation is “only regularly found” in synchronous fireflies in North America (they mention four more

Photinus species including

P. carolinus) and in Southeast Asia. Wing et al. [

15], p.89, mention that the copulation of

Pteroptyx valida, a synchronous firefly from Thailand, “occurs amidst high densities of intensely competing males” and suggest that the male mating “clamp” formed by the terminal part of the abdomen and the posterior tip of the elytra could have evolved to “prevent take-over of the female by other males during copulation”.

The very large numbers of males competing for the attention of the relatively scant receptive females makes synchronous fireflies a potential problem for the non-synchronous, much less abundant, sympatric firefly species. The male-biased OSR observed in synchronous fireflies results in intense competition for mates that could select for decreased male choosiness and increased willingness to approach, court, and attempt mating with any signaling female (or even male) firefly including heterospecific individuals [

1,

2,

17]. The similitude of the mating signals of the interacting species could also affect the occurrence and frequency of interspecific sexual interactions [

17]. This situation could result in mistaken approaches and courtship or mating attempts with females of other sympatric firefly species that also employ bioluminescent signals. If these interactions have a negative effect on female and/or male fitness, we have a case of reproductive interference [

1,

2,

4,

5], a potentially powerful selective pressure that could affect the evolution of bioluminescent signals and other elements of the mating sequence [

18]. However, as mentioned above, we could not find reports of naturally occurring interspecific sexual interactions between firefly species, with the exception of those induced by the aggressive mimicry of

Photuris spp. females [

7]. Lloyd [

17] explored the possibility of interspecific sexual interactions between

Photinus species of the USA by employing an experimental approach; we consider this work in the discussion.

In this paper, we report the results of an observational field study of the interactions between males of the synchronous firefly

Photinus palaciosi Zaragoza-Caballero attempting to court and mate with females of the much larger, and much less abundant, non-synchronous

P. extensus Gorham (

Figure 1A,B), two endemic species of Central Mexico [

19,

20]. Our investigation was inspired by the similarities in the mate location and courtship behavior (together, the mating sequence) of both species (although we have not yet studied their luminous signals), which also share female brachyptery (elytra and wing reduction that makes females unable to fly), and by three serendipitous observations of this type of interaction in a locality where both species coexist (see

Section 3.1).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of spontaneous interspecific courtship and mating attempts in fireflies under natural conditions. Of course, predatory females of many

Photuris species rely on sexual deception to attract male prey from other firefly species [

7], but in the case we report here, males and females emitted and/or responded to signals produced to obtain mates. Lloyd [

17] explored the possibility of interspecific sexual interactions between

Photinus species of the USA (he did not include the synchronous

P. carolinus) with an experimental approach by exposing, in “glass cages” or petri dishes, females of one species in places where males of a different species were actively looking for females. Lloyd tested ten different pairs of species using 12 different species. Sample sizes were usually small (in six species pairs, the number of females tested was six or less), although in two cases, he tested “numerous”/“several” females. In four species pairs, Lloyd [

17] observed interactions similar to courtship, and in three of them, there was physical contact between males and females, including one copula between the only tested female of

P. granulatus and a

P. tenuicinctus male. It is interesting that the case that resulted in copulation involved species with brachypterous females, whereas in two species pairs that interacted but did not attempt copulation, the females of only one of the species were brachypterous. The overlap of mating sites also did not explain the patterns: although five species pairs in which no interactions were observed were sympatric, two of the four species pairs in which males and females interacted were also sympatric. Differences between signals do not explain the results because in eight pairs of species, the signals of each species were different. However, it is interesting that the case in which a copula was observed involved allopatric species with similar signals. In our opinion, Lloyd’s [

17] experimental observations of interactions similar to courtship in four out of the ten tested species pairs (including one interspecific copulation) suggest that interspecific courtship in nature is probably more common than we know. Furthermore, we suggest that this could be especially true when one of the involved species is a synchronous firefly, as explained below.

We think that the simplest explanation for our behavioral observations is that

P. palaciosi males mistakenly courted

P. extensus females. These females were sexually receptive because they were actively emitting luminous signals during the mating period. We suggest that the

P. extensus females mistakenly responded to the bioluminescent signals of

P. palaciosi, which, in turn, mistakenly interpreted these responses as produced by females of their own species and courted the heterospecific females. The males of

P. palaciosi, as all synchronous fireflies, experience intense competition for females as a result of the typically large number of males looking for females every night (see [

15,

16]). Although we have not measured the operational sex ratio (OSR: the number of sexually receptive females divided by the number of sexually active males) in

P. palaciosi, our experience in the studied population, as well as in other populations of Central Mexico, indicates that the OSR is biased, probably heavily, towards males, which could increase the intensity of male competition for mates. As discussed in the Introduction, male-biased OSRs are probably typical of synchronous fireflies. This intense competition for females could have selected for males with enhanced willingness to approach, court, and attempt mating with any firefly roughly resembling a female of their own species [

1,

2], and this could explain the male mistakes reported in this paper. Furthermore, factors such as a preference for large females could facilitate even more of this type of mistake. Although a previous study failed to detect an effect of female size on the probability of mating in

P. palaciosi, that study was correlative and based on the natural variation in female size observed in the field [

21]. Thus, we cannot discard the possibility that the large females of

P. extensus (and their signals) are a supernormal stimulus [

25] for the mate searching males of

P. palaciosi. The observations that some

P. palaciosi males approached and courted perched males of

P. extensus provides further support to the idea that

P. palaciosi males are somewhat indiscriminate in their responses. What is more difficult to explain is the behavior of

P. extensus females. Their behavior during interactions was similar to that exhibited when interacting with conspecific males. If the females do not pay any fitness cost from these interactions, no discriminatory behavior is expected to evolve. However, there are reasons to think that these interactions are costly for them.

We do not know for certain if the interspecific courtship between

P. palaciosi males and

P. extensus females results in reproductive interference because we have no data on the effects of these interactions on the fitness of males and females of

P. palaciosi and

P. extensus. However, our observations led us to suggest that it is possible that the fitness of

P. extensus females is negatively affected, even though their “passivity” does not suggest a large investment of energy in these interactions. The large disparity in the density of mate-locating males of both species and the possibly male-biased OSR of

P. palaciosi are, very probably, responsible for the high frequency of interspecific courtship interactions [

1,

2,

4,

5]. Considering that the

P. extensus females courted by

P. palaciosi males stop signaling and responding to their own males and that a significant proportion of the interspecific interactions encompasses most of the nightly

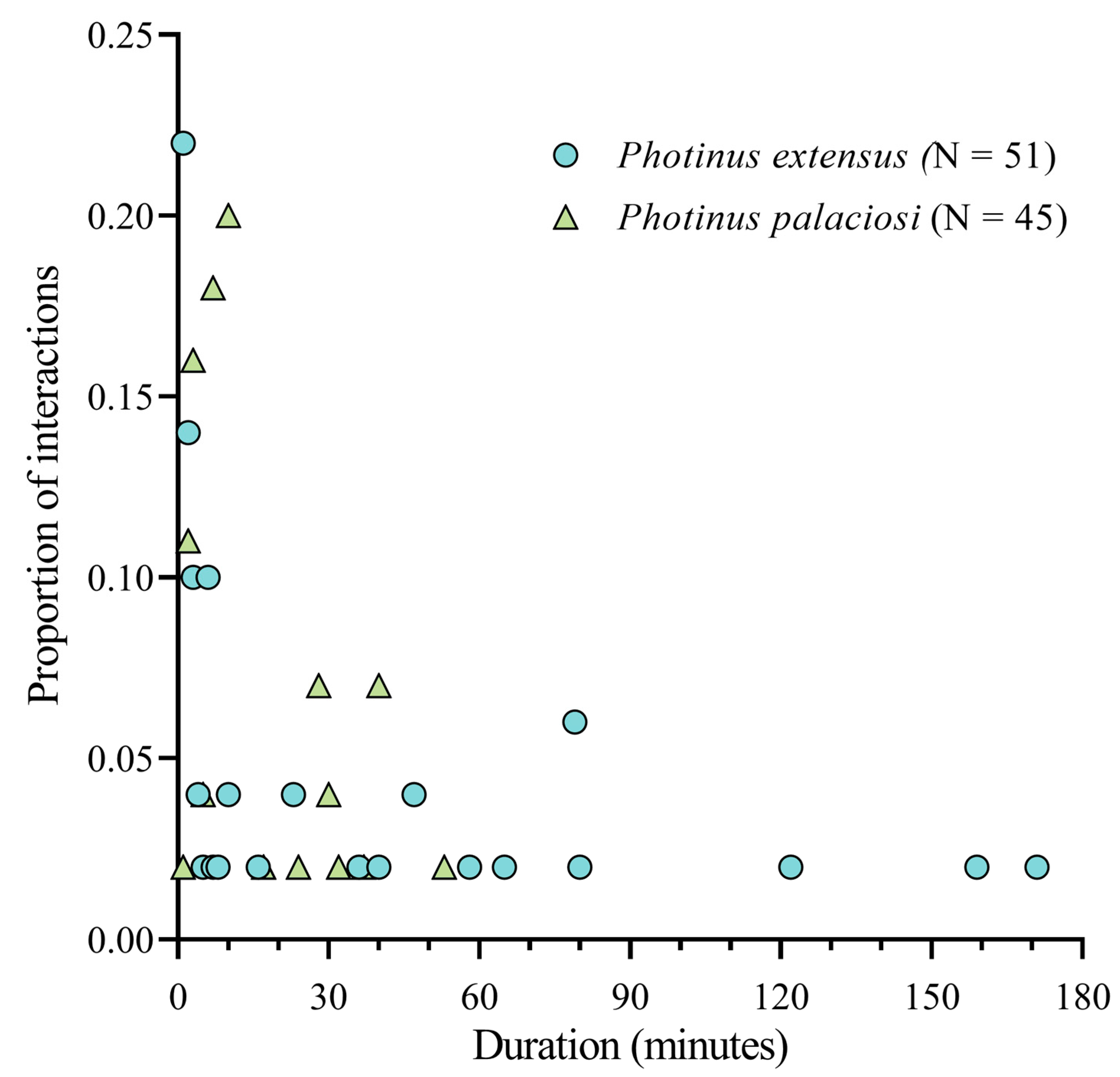

P. extensus mate location and courtship period (

Figure 4), it is possible that the females courted by heterospecific males will mate days later than other females or, in the worst case, fail to find a mate, which could result in a fitness decrease. Additionally, we have evidence that

P. extensus females are polyandrous (of the 10 females observed more than one night, two mated two times and one three times) and that males transfer spermatophores during copulation (AV, YM and CC, unpublished observations). Since spermatophores have been shown to contain valuable resources for females beyond sperm [

26,

27,

28,

29], interspecific courtship could reduce the amount of spermatophore resources obtained by the females. Furthermore, possible negative effects of interspecific courtship on future intraspecific courtships, such as the impaired receptivity observed in female

Nasonia longicornis wasps courted by males of a

N. vitripennis [

30], must also be investigated. In the case of

P. palaciosi males, they obviously spent more energy in the interspecific interactions than

P. extensus females. However, we think that due to the male-biased OSR, many (probably most) male

P. palaciosi do not mate in any given night, thus reducing the negative impact of these interactions on male fitness. Of course, this is a hypothesis that also needs to be tested. On the other hand, although the benefits of interspecific sexual interactions seem unlikely in this case, until experimental investigations are conducted, we cannot discard the possibility. Two hypothetical benefits (without any empirical support) help us to illustrate this possibility: females courted by heterospecific males could improve their mate choice abilities or males courting heterospecific females could improve their courting ability. Although these potential benefits could sound far-fetched, examples of unexpected benefits of other kinds of non-reproductive sexual behaviors (see, for example, ref. [

31] for a reproductive benefit of receiving homosexual courtship when immature for male

Drosophila melanogaster) suggest we should not hurry in discarding ideas without experimental tests.

If our suspicions about the costs involved are true, reproductive interference is acting as a selective pressure on the fireflies we studied. The consequences of this interaction could affect the evolution of the sexual communication systems (i.e., the signals and responses) of both species [

6] and even have an impact on the diversity of fireflies. For example, if the negative effects on

P. extensus are strong, the populations interacting with the synchronous

P. palaciosi could become extinct. Since

P. extensus is a species endemic to Central Mexico, an area heavily impacted by human activity, its risk of extinction could increase. Alternatively, if the communication system of

P. extensus evolves to prevent reproductive interference, populations interacting with

P. palaciosi could diverge from those not suffering reproductive interference, possibly initiating a speciation process. Thus, further study of reproductive interference by synchronous fireflies seems a promising avenue of research.