Turnover, Uniqueness, and Environmental Filtering Shape Helminth Parasite Metacommunities in Freshwater Fish Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Community Structure

2.2. Partitioning of β-Diversity

2.3. Local and Species Contribution to β-Diversity

2.4. Elements Metacommunity Structure Framework

2.5. Variance Models to Evaluate Environmental Factors and Host Size

3. Results

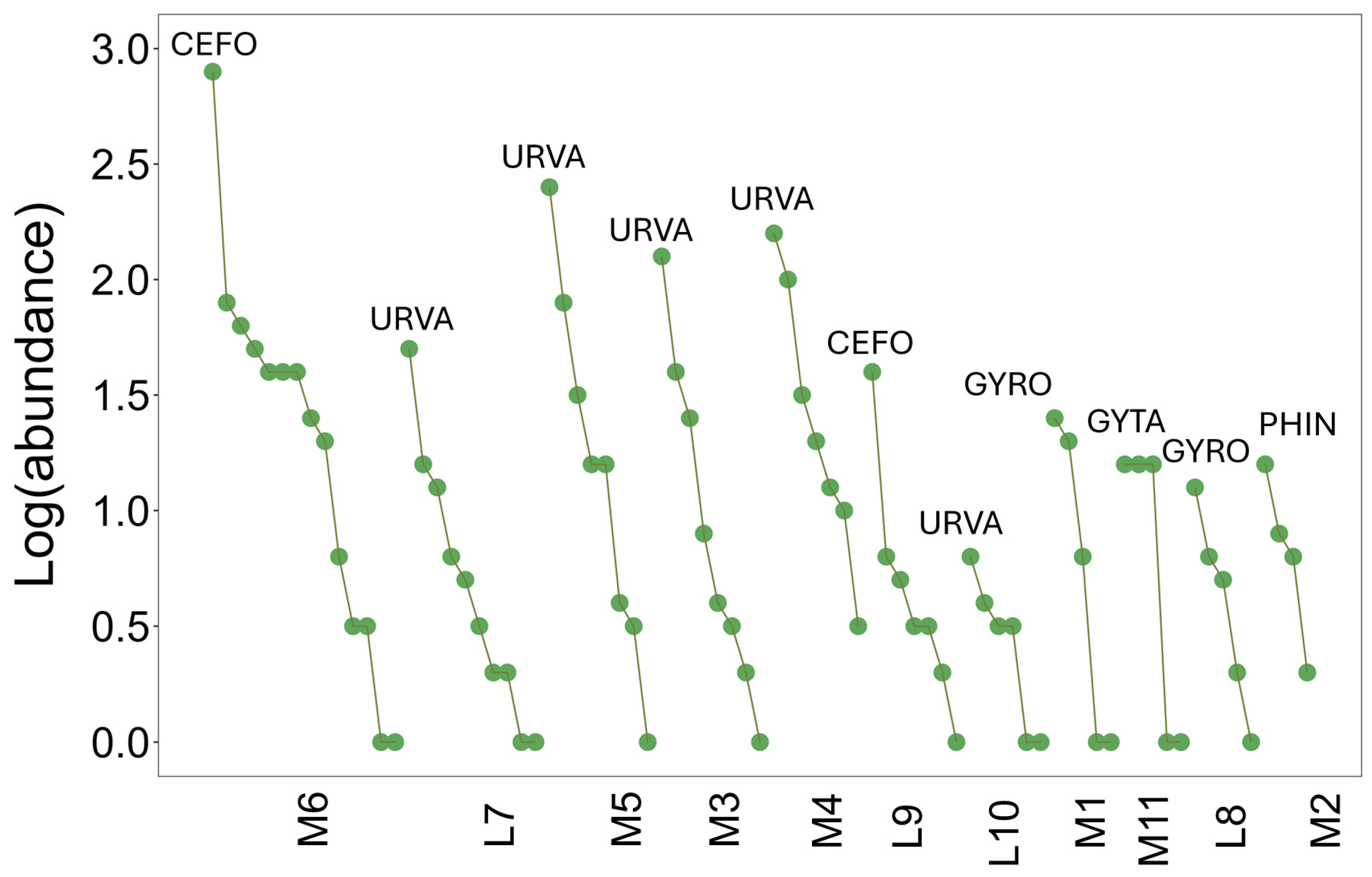

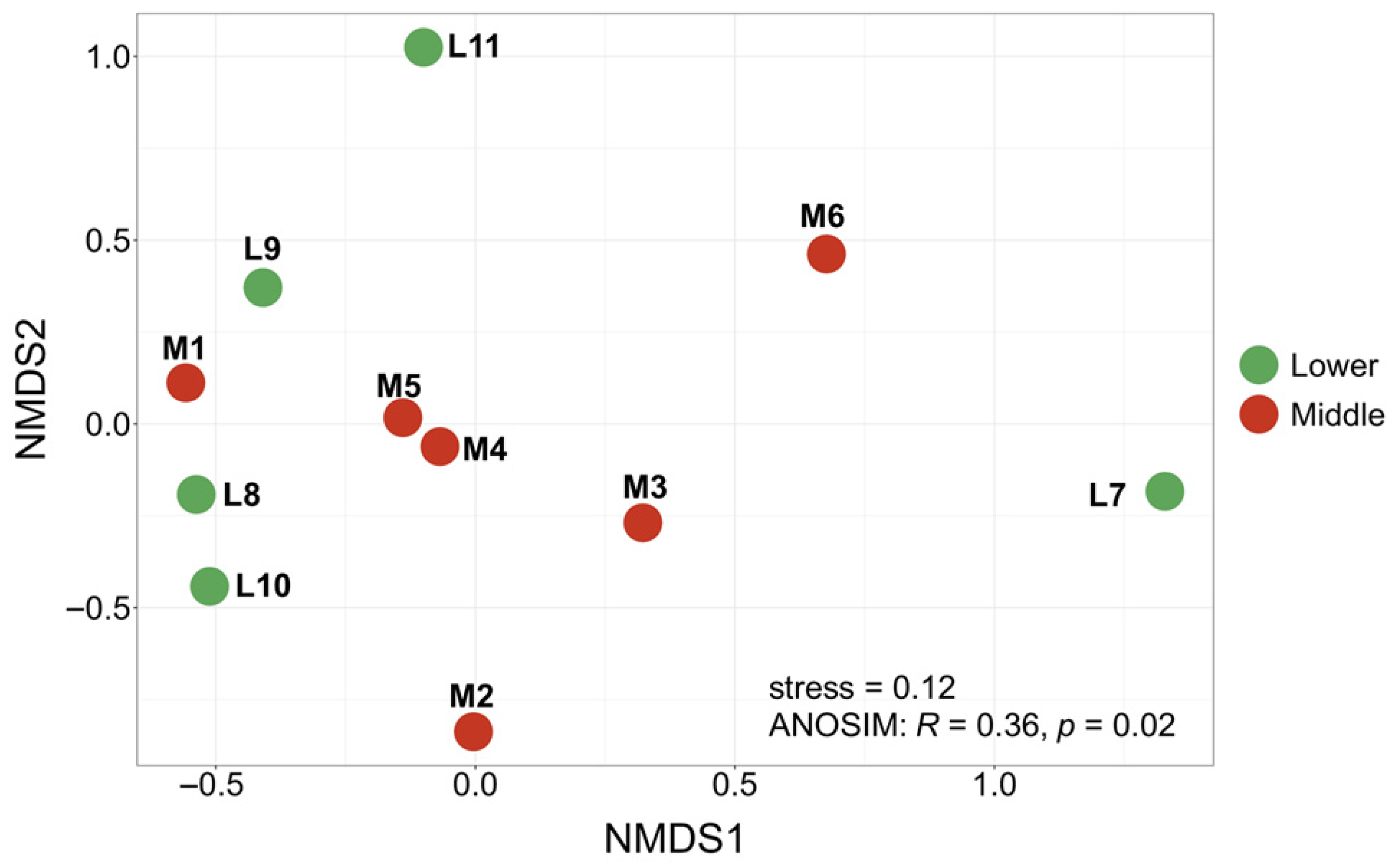

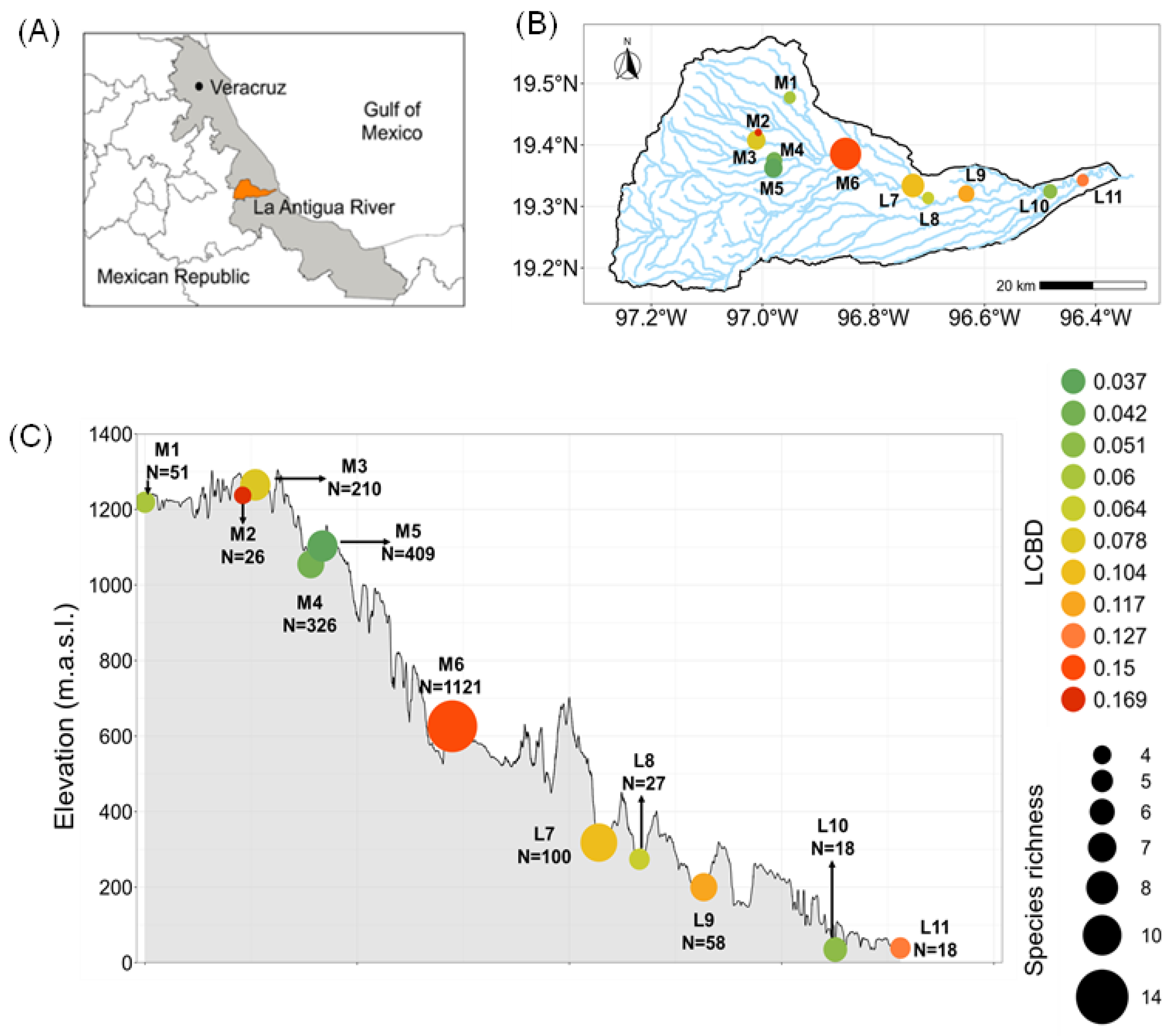

3.1. Community Structure

3.2. Partitioning of β-Diversity

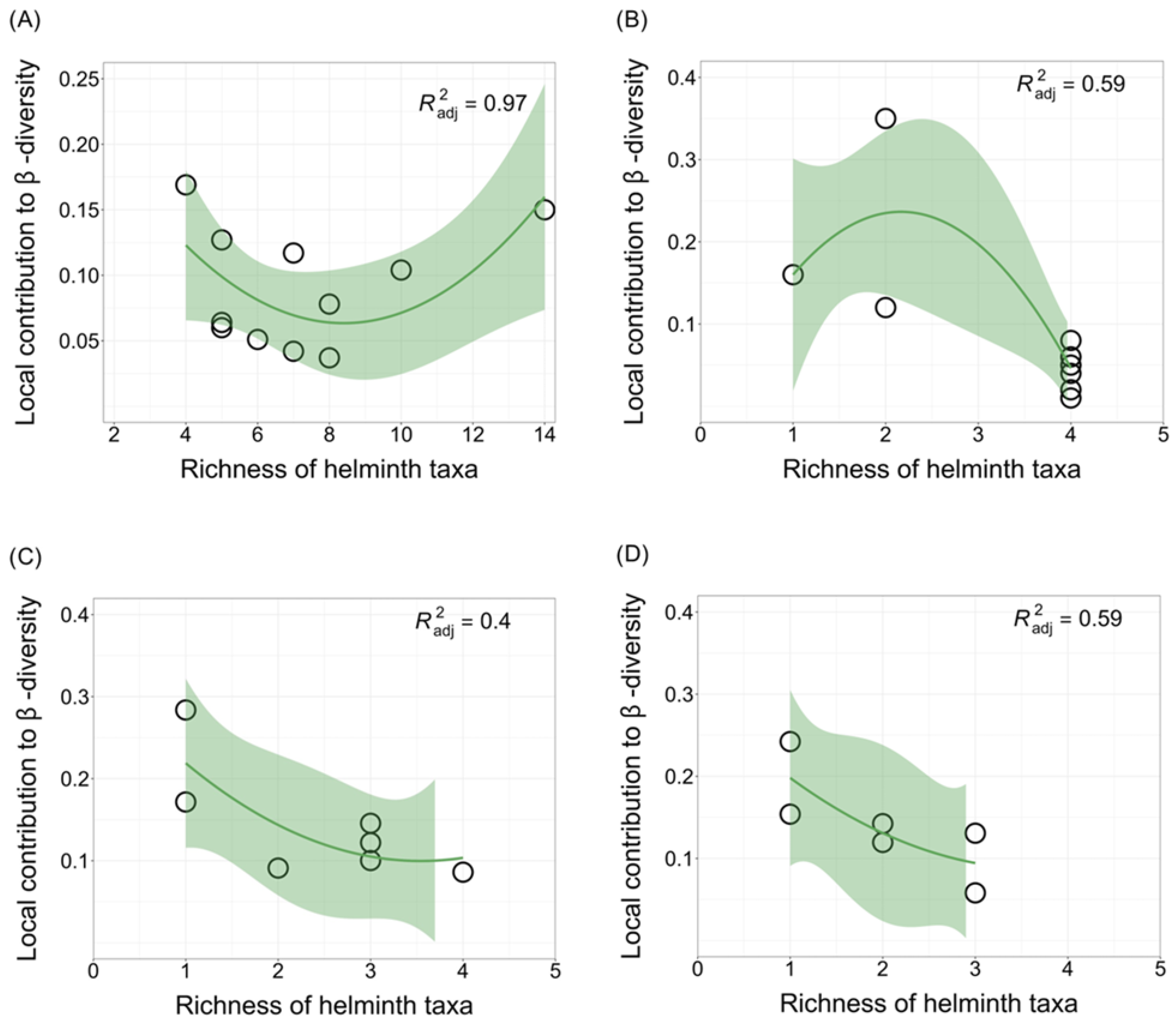

3.3. Local and Species Contributions to β-Diversity

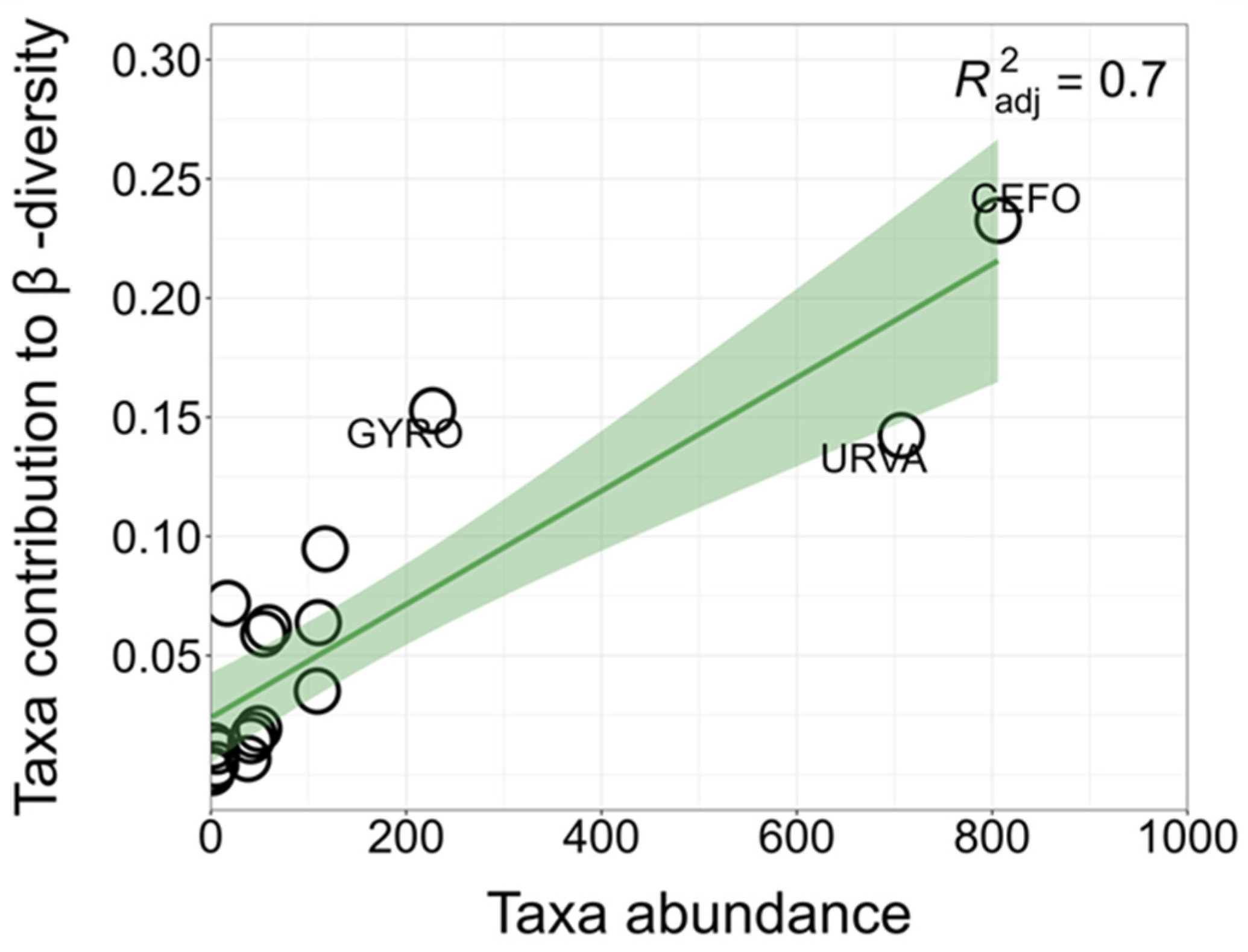

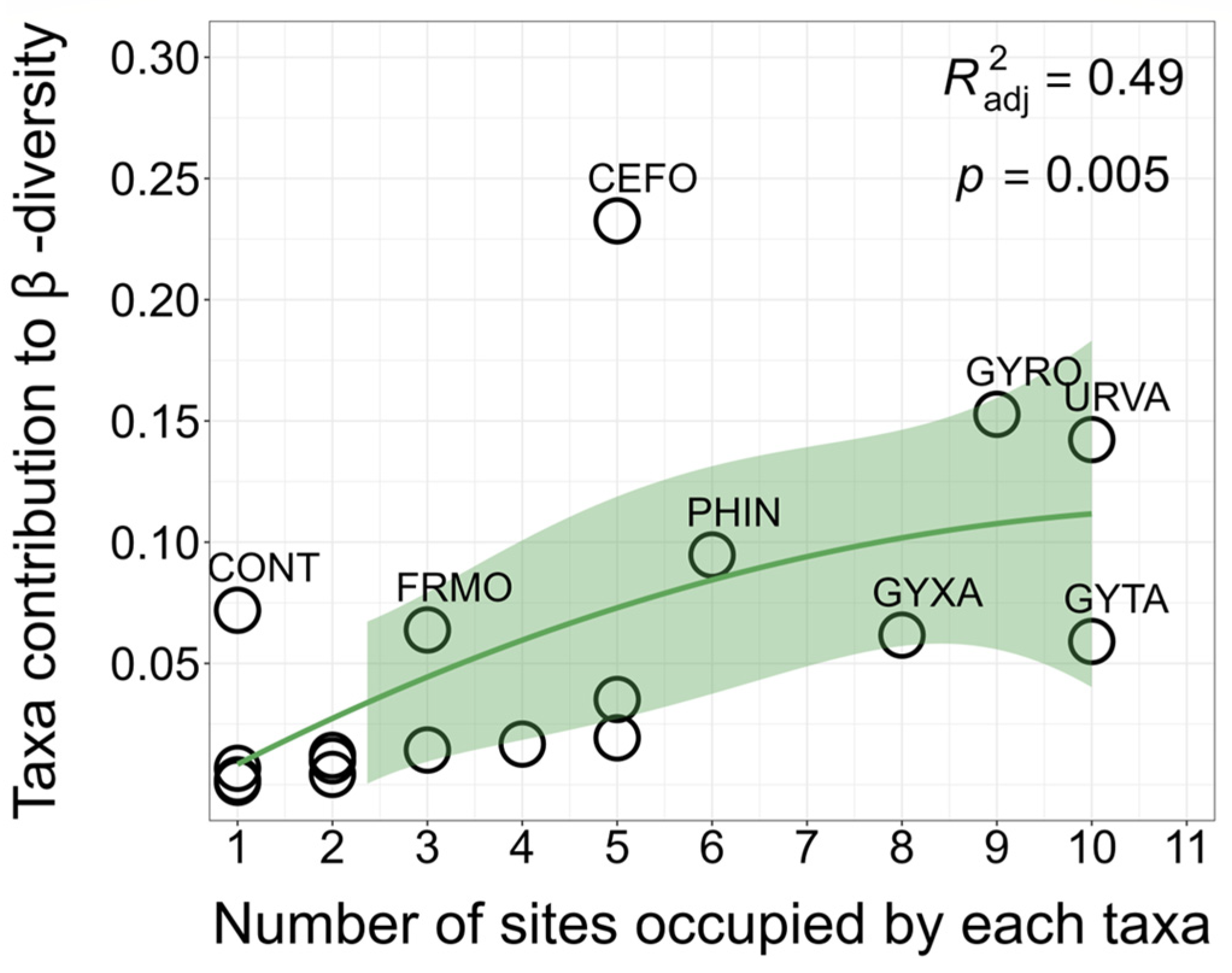

3.4. Metacommunity Structure (EMS Framework)

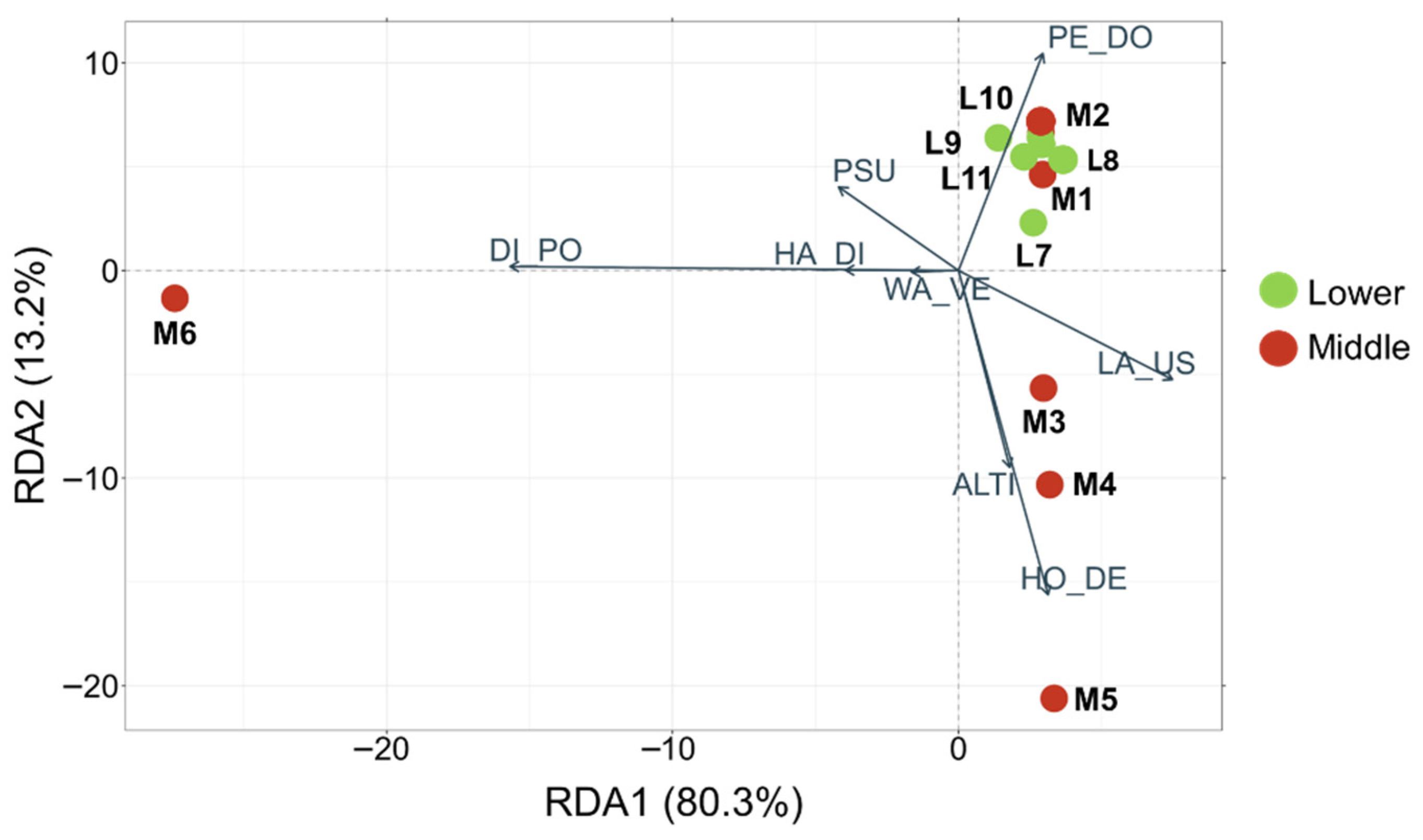

3.5. Environmental Drivers of Community Composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| dBC | Abundance-based multiple-site dissimilarity Bray–Curtis index |

| dBG.GRA | Partitioned beta diversity into abundance gradients |

| dBC.BAL | Partitioned beta diversity into balanced variation in abundance |

| LCBD | Local contribution to beta diversity |

| SCBD | Species contribution to beta diversity |

| EMS | Elements metacommunity structure |

References

- Moss, W.E.; McDevitt-Galles, T.; Calhoun, D.M.; Johnson, P.T.J. Tracking the assembly of nested parasite communities: Using β-diversity to understand variation in parasite richness and composition over time and scale. J. Anim. Ecol. 2020, 89, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, E.M.; Budischak, S.A.; Jolles, A.E.; Ezenwa, V.O. Within-host and external environments differentially shape β-diversity across parasite life stages. J. Anim. Ecol. 2023, 92, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcogliese, D.J. Parasites: Small players with crucial roles in the ecological theater. EcoHealth 2004, 1, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, A.; Lafferty, K.D.; Kuris, A.M.; Hechinger, R.F.; Jetz, W. Homage to Linnaeus: How many parasites? How many hosts? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11482–11489. [Google Scholar]

- Kuris, A.M.; Hechinger, R.F.; Shaw, J.C.; Whitney, K.L.; Aguirre-Macedo, M.L.; Boch, C.A.; Dobson, A.P.; Dunham, E.J.; Fredensborg, B.L.; Huspeni, T.C.; et al. Ecosystem energetic implications of parasite and free-living biomass in three estuaries. Nature 2008, 454, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D.L.; Mischler, J.A.; Townsend, A.R.; Johnson, P.T. Disease ecology meets ecosystem science. Ecosystems 2016, 19, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej-Sobocińska, M. Factors affecting the spread of parasites in populations of wild European terrestrial mammals. Mamm. Res. 2019, 64, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.R. Metapopulation and community dynamics of helminth parasites of eels Anguilla anguilla in the River Exe system. Parasitology 2001, 122, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibold, M.A.; Holyoak, M.; Mouquet, M.; Amarasekare, P.; Chase, J.M.; Hoopes, M.F.; Holt, R.D.; Shurin, J.B.; Law, R.; Tilman, D.; et al. The metacommunity concept: A framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibold, M.A.; Mikkelson, G.M. Coherence, species turnover, and boundary cumpling: Elements of metacommunity structure. Oikos 2002, 97, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, S.J.; Higgins, C.L.; Willing, M.R. A comprehensive framework for the evaluation of metacommunity structure. Oikos 2010, 119, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljevic, J.R. Linking metacommunity theory and symbiont evolutionary ecology. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljevic, J.R.; Hoye, B.J.; Johnson, P.T.J. Parasite metacommunities: Evaluating the roles of host community composition and environmental gradients in structuring symbiont communities within amphibians. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, S.J.; Willing, M.R. Gradients and the structure of Neotropical metacommunities: Effects of disturbance, elevation, landscape structure, and biogeography. In Neotropical Gradients and Their Analysis; Myster, R.W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 419–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H. Vegetation of the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon and California. Ecol. Monogr. 1960, 30, 279–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. The relationship between species replacement, dissimilarity derived from nestedness, and nestedness. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning abundance-based multiple-site dissimilarity into components: Balanced variation in abundance and abundance gradients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017, 8, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: Dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borcard, D.; Legendre, P.; Drapeau, P. Partialling out the spatial component of ecological variation. Ecology 1992, 73, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres-Neto, P.R.; Legendre, P.; Dray, S.; Borcard, D. Variation partitioning of species data matrices estimation and comparison of fractions. Ecology 2006, 87, 2614–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallas, T.; Presley, S.J. Relative importance of host environment, transmission potential and host phylogeny to the structure of parasite metacommunities. Oikos 2014, 123, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickett, A.; Matthee, S.; van der Mescht, L.; Junker, K.; Krasnov, B.; Haukisalmi, V. Beta diversity of gastrointestinal helminths in two closely related South African rodents: Species and site contributions. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 2863–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, J.; Bini, L.M.; Andersson, J.; Bergsten, J.; Bjelke, U.; Johansson, F. Unravelling the correlates of species richness and ecological uniqueness in a metacommunity of urban pond insects. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Trujillo, J.D.; Donato-Rondon, J.C.; Muñoz, I.; Sabater, S. Historical processes constrain metacommunity structure by shaping different pools of invertebrate taxa within the Orinoco basin. Divers. Distrib. 2020, 26, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolnick, D.I.; Resetarits, E.J.; Ballare, K.; Stuart, Y.E.; Stutz, W.E. Scale-dependent effects of host patch traits on species composition in a stickleback parasite metacommunity. Ecology 2020, 101, e03181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolnick, D.I.; Resetarits, E.J.; Ballare, K.; Stuart, Y.E.; Stutz, W.E. Host patch traits have scale-dependent effects on diversity in a stickleback parasite metacommunity. Ecology 2020, 43, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.P.L.; Takemoto, R.M.; Lizama, M.A.P.; Padial, A.A. Metacommunity of a host metapopulation: Explaining patterns and structures of a fish parasite metacommunity in a Neotropical floodplain basin. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 5103–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, T.S.; Costa-Neto, S.F.; Braga, C.; Weksler, M.; Simões, R.O.; Maldonado, A., Jr.; Luque, J.L.; Gentile, R. Helminth metacommunity of small mammals in a Brazilian reserve: The contribution of environmental variables, host attributes and spatial variables in parasite species abundance. Community Ecol. 2020, 21, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnov, B.R.; Korallo-Vinarskaya, N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Khokhlova, I.S. Temporal variation of metacommunity structure in arthropod ectoparasites harboured by small mammals: The effects of scale and climatic fluctuation. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Maldonado, G.; Caspeta-Mandujano, J.M.; Mendoza-Franco, E.F.; Rubio-Godoy, M.; García-Vásquez, A.; Mercado-Silva, N.; Guzmán-Valdivieso, I.; Matamoros, W. Competition from sea to mountain: Interactions and aggregation in low-diversity monogenean and endohelminth communities in twospot livebearer Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Teleostei: Poeciliidae) populations in a neotropical river. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 9115–9131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Silva, N.; Lyons, J.; Díaz-Pardo, E.; Navarrete, S.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, A. Environmental factors associated with fish assemblage patterns in a high gradient river of the Gulf of Mexico slope. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2012, 83, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Maldonado, G.; Caspeta-Mandujano, J.M.; Mendoza-Franco, E.F.; Rubio-Godoy, M.; García-Vásquez, A.; Mercado-Silva, N.; Guzmán-Valdivieso, I.; Matamoros, W. Data from monogenean and endohelminth communities in twospot livebearer Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Teleostei: Poeciliidae) populations in a neotropical river. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindt, R. Tree Diversity Analysis: A Manual and Software for Common Statistical Methods for Ecological and Biodiversity Studies; Using the BiodiversityR Software Within the R 2.6.1 Environment; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, R Package Version 2.4-3; The Comprehensive R Archive Network: Vienna, Austria, 2017. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Baselga, A. Separating the two components of abundance-based dissimilarity: Balanced changes in abundance vs. abundance gradients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A.; Orme, C. betapart: An R package for the study of beta diversity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzobom, U.M.; Heino, J.; Brito, M.T.S.; Landeiro, V.L. Untangling the determinants of macrophyte beta diversity in tropical floodplain lakes: Insights from ecological uniqueness and species contributions. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 82, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, S.J. On the detection of metacommunity structure. Community Ecol. 2020, 21, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, T. metacom: An R package for the analysis of metacommunity structure. Ecography 2014, 37, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Muneepeerakul, R.; Olden, J.D.; Lytle, D.A. The effect of spatial configuration of habitat capacity on β diversity. Ecosphere 2015, 6, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Costa, I.; Anson, V.K.; Martin, A.; Poulin, R. Upstream-downstream gradient in infection levels by fish parasites: A common river pattern? Parasitology 2013, 140, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglioretti, V.; Rossin, M.A.; Levy, E.; Timi, J.T. Parasite β-diversity along a stream: Effect of distance and environment. Int. J. Parasitol. 2024, 54, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, R.; Blanar, C.A.; Thieltges, D.W.; Marcogliese, D.J. The biogeography of parasitism in sticklebacks: Distance, habitat differences and the similarity in parasite occurrence and abundance. Ecography 2011, 34, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Bastiani, E.; Campião, K.M. Disentangling the beta-diversity in anuran parasite communities. Parasitology 2021, 148, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo-Tomás, P.; Olea, P.P.; Selva, N.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. Species and individual replacements contribute more than nestedness to shape vertebrate scavenger metacommunities. Ecography 2019, 42, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, P.G.; Hernández, M.I.M.; Heino, J. Disentangling the correlates of species and site contributions to beta diversity in dung beetle assemblages. Divers. Distrib. 2018, 24, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Lu, J.; Franklin, S.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, M. Beta diversity determinants in Badagongshan, a subtropical forest in central China. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.R.; Martins, R.T.; Bellei, P.M.; Lima, S.S. Aspectos ecológicos da helmintofauna de Hoplias malabaricus (Bloch, 1974) (Characiformes, Erythrinidae) da Represa Dr. João Penido (Juiz de Fora-MG, Brasil). Rev. Bras. Zoociênc. 2017, 18, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, J.; Grönroos, M. Exploring species and site contributions to beta diversity in stream insect assemblages. Oecologia 2017, 183, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, J.; Melo, A.S.; Siqueira, T.; Soininen, J.; Valanko, S.; Bini, L.M. Metacommunity organization, spatial extent, and dispersal in aquatic systems: Patterns, processes, and prospects. Freshw. Biol. 2015, 60, 845–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, K.; Dey, D.; Shruti, M.; Uniyal, V.P.; Adhikari, B.S.; Johnson, J.A.; Hussain, S.A. β-diversity of odonate community of the Ganga River: Partitioning and insights from local and species contribution. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 31, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M. Data for: Local contributions to beta-diversity in urban pond networks: Implications for biodiversity conservation and management. Dryad 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Belenguer, C.; Balbuena, J.A.; Lange, K.; de Bello, F.; Blasco-Costa, I. Towards a unified functional trait framework for parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenn, J.; Wolfenden, A.; Young, S.; Goertz, S.; Lowe, A.; MacColl, A.; Taylor, C.; Bradley, J. It’s all connected: Parasite communities of a wild house mouse population exist in a network of mixed positive and negative associations across guilds. Authorea 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnov, B.R.; Shenbrot, G.I.; Warburton, E.M.; van der Mescht, L.; Surkova, E.N.; Medvedev, S.G.; Pechnikova, N.; Ermolova, N.; Kotti, B.K.; Khokhlova, I.S. Species and site contributions to β-diversity in fleas parasitic on the Palearctic small mammals: Ecology, geography and host species composition matter the most. Parasitology 2019, 146, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Ma, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, C.L. The contribution of common and rare species to species abundance patterns in alpine meadows: The effect of elevation gradients. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goater, C.P.; Baldwin, R.E.; Scrimgeour, G.J. Physico-chemical determinants of helminth component community structure in whitefishes (Coregonus clupeaformes) from adjacent lakes in Northern Alberta, Canada. Parasitology 2005, 131, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanar, C.A.; Hewitt, M.; McMaster, M.; Kirk, J.; Wang, Z.; Norwood, W.; Marcogliese, D.J. Parasite community similarity in Athabasca River trout-perch (Percopsis omiscomaycus) varies with local-scale land use and sediment hydrocarbons, but not distance or linear gradients. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 3853–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.P.; Araújo, S.B.L.; Boeger, W.A. Patterns of interaction between Neotropical freshwater fishes and their gill Monogenoidea (Platyhelminthes). Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimková, A. Host-specific monogeneans parasitizing freshwater fish: The ecology and evolution of host-parasite associations. Parasite 2024, 31, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.A.; Blazek, K.J.; Percival, T.J.; Janovy, J.J. The niche of the gill parasite Dactylogyrus banghami (Monogenea: Dactylogyridae) on Notropis stramineus (Pisces: Cyprinidae). J. Parasitol. 1993, 79, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimková, A.; Desdevises, Y.; Gelnar, M.; Morand, S. Co-existence of nine gill ectoparasites (Dactylogyrus: Monogenea) parasitising the roach (Rutilus rutilus L.): History and present ecology. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000, 30, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, S.; Simková, A.; Matejusová, I.; Plaisance, L.; Verneau, O.; Desdevises, Y. Investigating patterns may reveal processe: Evolutionary ecology of ectoparasitic monogeneans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002, 32, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibold, M.A.; Chase, J.M. Metacommunity Ecology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.E. Helminth host-environment interactions: Looking down from the tip of the iceberg. J. Helminthol. 2023, 97, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmera, D.; Árva, D.; Boda, P.; Bódis, E.; Bolgovics, A.; Borics, G.; Csercsa, A.; Deák, C.; Krasznai, E.A.; Lukács, B.A.; et al. Does isolation influence the relative role of environmental and dispersal-related processes in stream networks? An empirical test of the network position hypothesis using multiple taxa. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 63, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañedo-Argüelles, M.; Gutiérrez-Cánovas, C.; Acosta, R.; Castro-López, D.; Cid, N.; Fortuño, P.; Munné, A.; Múrria, C.; Pimentão, A.R.; Sarremejane, R.; et al. As time goes by: 20 years of changes in the aquatic macroinvertebrate metacommunity of Mediterranean river networks. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 1861–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall Helminths 11 Localities, 220 Hosts | Monogeneans 11 Localities, 144 Hosts | Intestinal Adults 6 Localities; 75 Hosts | Larvae 6 Localities; 48 Hosts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localities | dBC.bal | dBC.gra | dBC | dBC.bal | dBC.gra | dBC | dBC.bal | dBC.gra | dBC | dBC.bal | dBC.gra | dBC |

| Between localities | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.98 |

| Between hosts | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.21 | 0.97 |

| M1 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 0.87 | ||||||

| M2 | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.87 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.68 | |||

| M3 | 0.68 | 0.20 | 0.88 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.87 | |||

| M4 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.88 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.82 | |||

| M5 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.89 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.74 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| M6 | 0.78 | 0.15 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.14 | 0.90 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.93 |

| L7 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.89 |

| L8 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.84 | ||||||

| L9 | 0.88 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.07 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.10 | 0.98 | |||

| L10 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| L11 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.86 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.83 | |||

| Site | Scale | Coherence | Turnover | Boundary Clumping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs | Mean | V | Rep | Mean | V | M. I. | Structure | ||

| Overall | Component communities | 46 * | 87.58 | 8.15 | 264 | 270.10 | 74.97 | 2.15 * | Nestedness (Clustered loss of species) |

| M1 | Infracommunities | 0 | 24.43 * | 5.80 | 111.0 | 57.66 | 29.44 | 0 | Quasi-Gleasonian |

| M2 | Infracommunities | 12.58 | 13.0 * | 3.04 | 47.0 | 26.16 | 15.78 | 4.5 * | Quasi-Clementsian |

| M3 | Infracommunities | 27.0 | 53.51 * | 8.20 | 386.0 | 229.98 | 95.43 | 1.54 | Quasi-Gleasonian |

| M4 | Infracommunities | 28.0 | 59.48 * | 6.55 | 287.0 | 111.36 * | 69.18 | 2.5 * | Clementsian |

| M5 | Infracommunities | 14.0 | 61.91 * | 7.87 | 194 | 170.49 | 58.59 | 2.07 * | Quasi-Clementsian |

| M6 | Infracommunities | 99.0 | 147.791 * | 9.84 | 817.0 | 369.86 * | 149.40 | 0.98 | Gleasonian |

| L7 | Infracommunities | 24.0 | 74.12 * | 11.15 | 258.0 | 161.29 * | 45.72 | 1.75 * | Clementsian |

| L8 | Infracommunities | 4.0 | 15.21 * | 3.71 | 90.0 | 58.20 | 27.12 | 1.79 | Quasi-Gleasonian |

| L9 | Infracommunities | 0 | 17.50 * | 4.64 | 67.0 | 49.35 | 9.69 | 1.8 * | Quasi-Clementsian |

| L10 | Infracommunities | 2.0 | 18.23 * | 4.38 | 70.0 | 53.24 | 14.74 | 1 | Quasi-Gleasonian |

| L11 | Infracommunities | 4.0 | 15.35 * | 3.07 | 48.03 | 39.96 | 20.19 | 1.57 | Quasi-Gleasonian |

| Variable | R2 | p |

|---|---|---|

| FQ + EH + LT | 0.86 | 0.002 * |

| FQ|EH + LT | 0.42 | 0.10 |

| EH|FQ + LT | 0.69 | 0.05 * |

| LT|FQ + EH | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| Residual | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-del-Monte, I.; Rico-Chávez, O.; Caspeta-Mandujano, J.M.; Mendoza-Franco, E.F.; Mercado-Silva, N.; Montoya-Mendoza, J.; Rubio-Godoy, M.; Guzmán-Valdivieso, I.; Quiroz-Martínez, B.; Salgado-Maldonado, G. Turnover, Uniqueness, and Environmental Filtering Shape Helminth Parasite Metacommunities in Freshwater Fish Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae). Diversity 2025, 17, 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120864

López-del-Monte I, Rico-Chávez O, Caspeta-Mandujano JM, Mendoza-Franco EF, Mercado-Silva N, Montoya-Mendoza J, Rubio-Godoy M, Guzmán-Valdivieso I, Quiroz-Martínez B, Salgado-Maldonado G. Turnover, Uniqueness, and Environmental Filtering Shape Helminth Parasite Metacommunities in Freshwater Fish Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae). Diversity. 2025; 17(12):864. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120864

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-del-Monte, Ivonne, Oscar Rico-Chávez, Juan Manuel Caspeta-Mandujano, Edgar Fernando Mendoza-Franco, Norman Mercado-Silva, Jesús Montoya-Mendoza, Miguel Rubio-Godoy, Ismael Guzmán-Valdivieso, Benjamín Quiroz-Martínez, and Guillermo Salgado-Maldonado. 2025. "Turnover, Uniqueness, and Environmental Filtering Shape Helminth Parasite Metacommunities in Freshwater Fish Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae)" Diversity 17, no. 12: 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120864

APA StyleLópez-del-Monte, I., Rico-Chávez, O., Caspeta-Mandujano, J. M., Mendoza-Franco, E. F., Mercado-Silva, N., Montoya-Mendoza, J., Rubio-Godoy, M., Guzmán-Valdivieso, I., Quiroz-Martínez, B., & Salgado-Maldonado, G. (2025). Turnover, Uniqueness, and Environmental Filtering Shape Helminth Parasite Metacommunities in Freshwater Fish Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae). Diversity, 17(12), 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120864