Long-Term Responses of Crustacean Zooplankton to Hydrological Alterations in the Danube Inland Delta: Patterns of Biotic Homogenization and Differentiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Description of Danube Inland Delta and Monitored Sites

2.2. Field Sampling and Data Processing

2.3. Homogenization Measurement and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

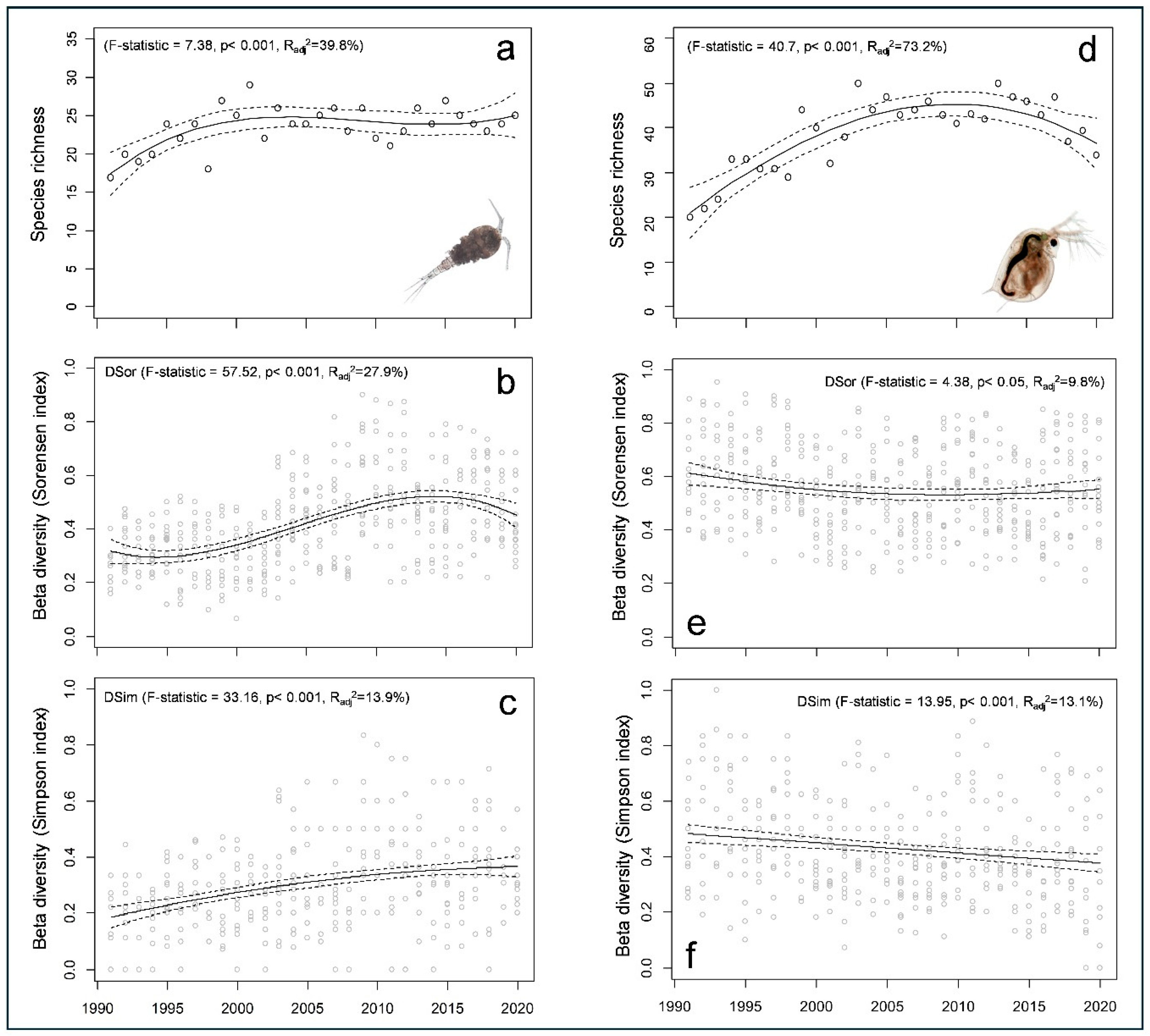

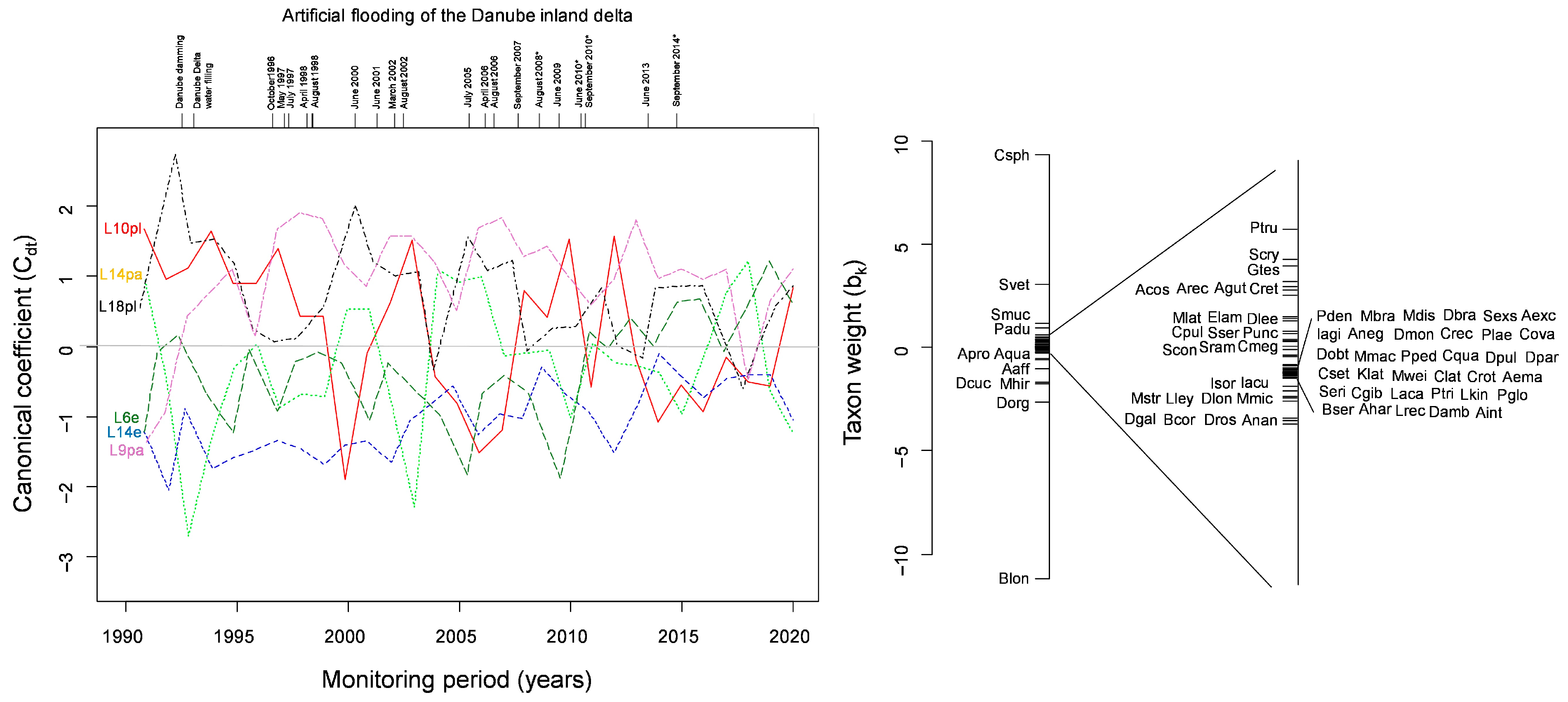

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Patterns in Taxonomic Diversity

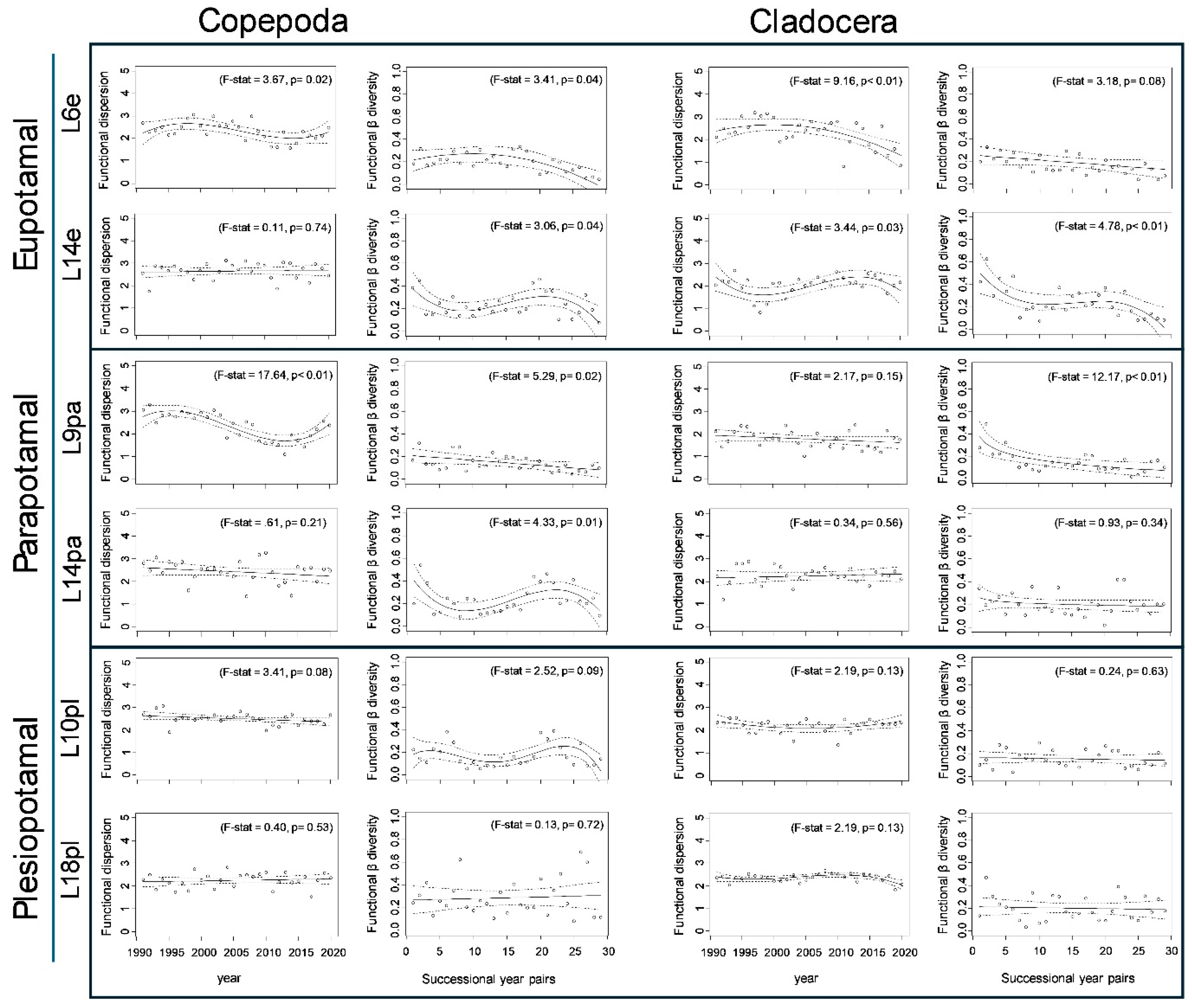

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Patterns in Functional Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Trait | Modality | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Mesohabitat affinity | tychoplanktonic species | Species preferred a benthic/littoral habitat |

| euplanktonic species | Species adapted for a planktonic/pelagic habitat | |

| small forms | species with maximum body size up to 1 mm | |

| Maximum body size | medium forms | species with the maximum body size between 1 and 2 mm |

| big forms | species with maximum body size over 2 mm | |

| capturer | Feeding strategy in which an organism actively seizes, traps, or ensnares its food | |

| primary filtrator | Feeding strategy in which an organism filters suspended particles directly from the water | |

| Feeding type | secondary filtrator | Feeding strategy in which an organism filters small particles or microorganisms that are resuspended from surfaces or loosely associated with biofilm |

| gatherer | Feeding strategy in which an organism collects fine particulate organic matter that has settled on surfaces as macrophytes, sediments, or biofilms. | |

| swimmer | Active, often continuous movement through water | |

| Locomotion type | crawler | Movement across surfaces, typical for benthic or epibenthic species. |

| clinger | Ability to attach to substrates; can be temporary or permanent. |

| Mesohabitat Affinity | Maximum Body Size | Feeding Type | Locomotion Type | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Copepoda | ||||||||||||

| Calanoida | ||||||||||||

| Diaptomus castor | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eudiaptomus gracilis | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eudiaptomus transylvanicus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eurytemora velox | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyclopoida | ||||||||||||

| Acanthocyclops einslei | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Acanthocyclops robustus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Acanthocyclops trajani | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Acanthocyclops vernalis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cryptocyclops bicolor | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Cyclops furcifer | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyclops heberti | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyclops strenuus | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyclops vicinus | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diacyclops bicuspidatus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diacyclops bisetosus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diacyclops crassicaudis | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diacyclops languidoides | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ectocyclops phaleratus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ergasilus sieboldi | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eucyclops denticulatus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eucyclops macruroides | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eucyclops macrurus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eucyclops serrulatus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eucyclops speratus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Macrocyclops albidus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Macrocyclops distinctus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Macrocyclops fuscus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Megacyclops viridis | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mesocyclops leuckarti | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Metacyclops gracilis | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Microcyclops rubellus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Microcyclops varicans | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Paracyclops affinis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Paracyclops fimbriatus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Paracyclops poppei | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Thermocyclops crassus | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Thermocyclops oithonoides | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Harpacticoida | ||||||||||||

| Attheyella trispinosa | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Attheyella crassa | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bryocamptus mrazeki | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bryocamptus vejdovskyi | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bryocamptus pygmaeus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bryocamptus zschokkei | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Canthocamptus staphylinus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ectinosoma abrau | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Echinocamptus pilosus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Elaphoidella bidens | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nitocra hibernica | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Tisbe furcata | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cladocera | ||||||||||||

| Anomopoda | ||||||||||||

| Acroperus harpae | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Acroperus neglectus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona affinis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona costata | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona guttata | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona intermedia | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona protzi | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona quadrangularis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alona rectangula | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alonella excisa | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Alonella nana | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Anchistropus emarginatus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Bosmina coregoni | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bosmina longirostris | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bunops serricaudata | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Camptocercus rectirostris | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia laticaudata | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia megops | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia pulchella | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia quadrangula | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia reticulata | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia rotunda | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceriodaphnia setosa | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia ambigua | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia cucullata | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia galeata | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia longispina | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia obtusa | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia parvula | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Daphnia pulicaria | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Disparalona leei | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Disparalona rostrata | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eurycercus lamellatus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Graptoleberis testudinaria | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Chydorus gibbus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Chydorus ovalis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Chydorus sphaericus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ilyocryptus acutifrons | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ilyocryptus agilis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ilyocryptus sordidus | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kurzia latissima | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lathonura rectirostris | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Leydigia acanthocercoides | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Leydigia leydigii | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Macrothrix hirsuticornis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Macrothrix laticornis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixopleuroxus striatoides | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Moina brachiata | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Moina macrocopa | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Moina micrura | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Moina weismanni | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Monospilus dispar | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Peracantha truncata | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleuroxus aduncus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleuroxus denticulatus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleuroxus laevis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleuroxus trigonellus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleuroxus uncinatus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pseudochydorus globosus | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Scapholeberis erinaceus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Scapholeberis mucronata | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Scapholeberis rammneri | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Simocephalus congener | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Simocephalus exspinosus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Simocephalus serrulatus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Simocephalus vetulus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ctenopoda | ||||||||||||

| Diaphanosoma brachyurum | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diaphanosoma mongolianum | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diaphanosoma orghidani | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sida crystallina | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Haplopoda | ||||||||||||

| Leptodora kindtii | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Onychopoda | ||||||||||||

| Polyphemus pediculus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Monitored Sites | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | L6e | L14e | L9pa | L14pa | L10pl | L18pl |

| Copepoda | ||||||

| Calanoida | ||||||

| Diaptomus castor | 1 | |||||

| Eudiaptomus gracilis | 16 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 20 | 14 |

| Eudiaptomus transylvanicus | 1 | |||||

| Eurytemora velox | 21 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 27 |

| Cyclopoida | ||||||

| Acanthocyclops einslei | 6 | 5 | 6 | 12 | 14 | 10 |

| Acanthocyclops robustus | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Acanthocyclops trajani | 4 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 8 |

| Acanthocyclops vernalis | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Cryptocyclops bicolor | 2 | 14 | 10 | 29 | 23 | |

| Cyclops furcifer | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Cyclops heberti | 2 | |||||

| Cyclops strenuus | 3 | 4 | 10 | |||

| Cyclops vicinus | 13 | 18 | 13 | 23 | 6 | 13 |

| Diacyclops bicuspidatus | 10 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 8 | |

| Diacyclops bisetosus | 1 | |||||

| Diacyclops crassicaudis | 1 | |||||

| Diacyclops languidoides | 3 | |||||

| Ectocyclops phaleratus | 1 | 7 | 5 | 23 | ||

| Ergasilus sieboldi | 1 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Eucyclops denticulatus | 1 | |||||

| Eucyclops macruroides | 8 | 4 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 11 |

| Eucyclops macrurus | 3 | 5 | 23 | 15 | 23 | 3 |

| Eucyclops serrulatus | 30 | 19 | 30 | 27 | 30 | 29 |

| Eucyclops speratus | 13 | 5 | 24 | 13 | 15 | 17 |

| Macrocyclops albidus | 17 | 5 | 27 | 30 | 28 | 30 |

| Macrocyclops distinctus | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Macrocyclops fuscus | 8 | 2 | 17 | 15 | ||

| Megacyclops viridis | 6 | 2 | 14 | 17 | 25 | |

| Mesocyclops leuckarti | 8 | 7 | 10 | 28 | 26 | 28 |

| Metacyclops gracilis | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Microcyclops rubellus | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Microcyclops varicans | 9 | 14 | ||||

| Paracyclops affinis | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Paracyclops fimbriatus | 26 | 9 | 16 | 9 | ||

| Paracyclops poppei | 1 | 7 | ||||

| Thermocyclops crassus | 11 | 13 | 6 | 27 | 30 | 25 |

| Thermocyclops oithonoides | 8 | 24 | 17 | 30 | 30 | 27 |

| Harpacticoida | ||||||

| Attheyella trispinosa | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Attheyella crassa | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Bryocamptus mrazeki | 1 | |||||

| Bryocamptus vejdovskyi | 1 | |||||

| Bryocamptus pygmaeus | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Bryocamptus zschokkei | 1 | |||||

| Canthocamptus staphylinus | 1 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 9 | |

| Ectinosoma abrau | 18 | 18 | 21 | 1 | 3 | |

| Echinocamptus pilosus | 1 | |||||

| Elaphoidella bidens | 2 | |||||

| Nitocra hibernica | 28 | 26 | 30 | 18 | 17 | 2 |

| Tisbe furcata | 8 | |||||

| Cladocera | ||||||

| Anomopoda | ||||||

| Acroperus harpae | 5 | 6 | 22 | 11 | 17 | 11 |

| Acroperus neglectus | 1 | 9 | 10 | 22 | 11 | |

| Alona affinis | 24 | 19 | 26 | 25 | 11 | 4 |

| Alona costata | 20 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Alona guttata | 5 | 3 | 25 | 11 | 22 | 8 |

| Alona intermedia | 1 | |||||

| Alona protzi | 17 | 17 | 16 | 2 | ||

| Alona quadrangularis | 19 | 15 | 18 | 10 | 2 | |

| Alona rectangula | 10 | 8 | 28 | 24 | 30 | 12 |

| Alonella excisa | 4 | 1 | 19 | 10 | ||

| Alonella nana | 11 | 8 | 15 | 3 | ||

| Anchistropus emarginatus | 2 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Bosmina coregoni | 10 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Bosmina longirostris | 26 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 28 | 23 |

| Bunops serricaudata | 5 | |||||

| Camptocercus rectirostris | 2 | 2 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Ceriodaphnia laticaudata | 6 | |||||

| Ceriodaphnia megops | 5 | 9 | 6 | 19 | ||

| Ceriodaphnia pulchella | 3 | 7 | 4 | 23 | 22 | 25 |

| Ceriodaphnia quadrangula | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Ceriodaphnia reticulata | 1 | 5 | 17 | |||

| Ceriodaphnia rotunda | 2 | |||||

| Ceriodaphnia setosa | 2 | |||||

| Daphnia ambigua | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Daphnia cucullata | 7 | 20 | 4 | 14 | 2 | 6 |

| Daphnia galeata | 17 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 11 |

| Daphnia longispina | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Daphnia obtusa | 4 | |||||

| Daphnia parvula | 1 | |||||

| Daphnia pulicaria | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Disparalona leei | 10 | 3 | 12 | 9 | ||

| Disparalona rostrata | 17 | 9 | 27 | 21 | 8 | |

| Eurycercus lamellatus | 8 | 7 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Graptoleberis testudinaria | 2 | 19 | 7 | 19 | 13 | |

| Chydorus gibbus | 2 | |||||

| Chydorus ovalis | 2 | |||||

| Chydorus sphaericus | 30 | 19 | 30 | 28 | 30 | 30 |

| Ilyocryptus acutifrons | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Ilyocryptus agilis | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | |

| Ilyocryptus sordidus | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Kurzia latissima | 1 | |||||

| Lathonura rectirostris | 8 | 1 | ||||

| Leydigia acanthocercoides | 1 | |||||

| Leydigia leydigii | 17 | 3 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Macrothrix hirsuticornis | 23 | 18 | 4 | 12 | 2 | |

| Macrothrix laticornis | 17 | 2 | 28 | 18 | 4 | |

| Mixopleuroxus striatoides | 6 | |||||

| Moina brachiata | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Moina macrocopa | 1 | |||||

| Moina micrura | 5 | 10 | 9 | 30 | 18 | 8 |

| Moina weismanni | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Monospilus dispar | 7 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Peracantha truncata | 2 | 26 | 4 | 9 | 9 | |

| Pleuroxus aduncus | 5 | 3 | 28 | 23 | 29 | 20 |

| Pleuroxus denticulatus | 7 | 5 | 27 | 24 | 22 | 15 |

| Pleuroxus laevis | 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Pleuroxus trigonellus | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Pleuroxus uncinatus | 21 | 13 | 10 | |||

| Pseudochydorus globosus | 3 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Scapholeberis erinaceus | 2 | |||||

| Scapholeberis mucronata | 10 | 3 | 24 | 28 | 26 | 27 |

| Scapholeberis rammneri | 3 | 15 | 13 | 19 | 15 | |

| Simocephalus congener | 8 | 12 | ||||

| Simocephalus exspinosus | 2 | |||||

| Simocephalus serrulatus | 18 | 20 | 23 | 12 | ||

| Simocephalus vetulus | 17 | 6 | 27 | 27 | 28 | 30 |

| Ctenopoda | ||||||

| Diaphanosoma brachyurum | 1 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 21 | 7 |

| Diaphanosoma mongolianum | 1 | 6 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Diaphanosoma orghidani | 6 | 23 | 5 | 17 | 10 | 9 |

| Sida crystallina | 8 | 3 | 24 | 21 | 25 | 23 |

| Haplopoda | ||||||

| Leptodora kindtii | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Onychopoda | ||||||

| Polyphemus pediculus | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

References

- Sommerwerk, N.; Hein, T.; Schneider-Jacoby, M.; Baumgartner, C.; Ostojic, A.; Siber, R.; Bloesch, J.; Paunovic, M.; Tockner, K. The Danube River Basin. In Rivers of Europe; Tockner, K., Robinson, C.T., Uehlinger, U., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 59–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tockner, K.; Schiemer, F.; Baumgartner, C.; Kum, G.; Weigand, E.; Zweimüller, I.; Ward, J.V. The Danube restoration project: Species diversity patterns across connectivity gradients in the floodplain system. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 1999, 15, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.V.; Tockner, K.; Arscott, D.B.; Claret, C. Riverine Landscape Diversity: Riverine Landscape Diversity. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănoiu, V.M.; Crăciun, A.I. Danube River water quality trends: A qualitative review based on the open access web of science database. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2021, 21, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittizer, T.; Banning, M. Biological assessment in the Danube catchment area: Indications of shifts in species composition induced by human activities. Eur. Water Manag. 2001, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bloesch, J. The International Association for Danube Research (IAD)—Portrait of a transboundary scientific NGO. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009, 16, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Naiman, R.J.; Magnuson, J.J.; McKnight, D.M.; Stanford, J.A.; Karr, J.R. Freshwater ecosystems and management: A national initiative. Science 1995, 270, 584–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Reich, P.B.; Knops, J.M.H. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment. Nature 2006, 441, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhotin, A.; Berger, V. Long-term monitoring studies as a powerful tool in marine ecosystem research. Hydrobiologia 2013, 706, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Callaway, R.M.; Van der Putten, W.H. Terrestrial ecosystem responses to species gains and losses. Science 2011, 332, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, S.; Iritani, R.; Cadotte, M.W. Temporal changes in spatial variation: Partitioning the extinction and colonisation components of beta diversity. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, D.F.; Gaines, S.D. Species diversity: From global decreases to local increases. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.D. Local diversity stays about the same, regional diversity increases, and global diversity declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19187–19188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellend, M.; Baeten, L.; Myers-Smith, I.H.; Elmendorf, S.C.; Beauséjour, R.; Brown, C.D.; De Frenne, P.; Verheyen, K.; Wipf, S. Global meta-analysis reveals no net change in local-scale plant biodiversity over time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19456–19459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Rooney, T.P. On defining and quantifying biotic homogenization. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2006, 15, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmendorf, S.C.; Harrison, S.P. Is plant community richness regulated over time? Contrasting results from experiments and long-term observations. Ecology 2011, 92, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sax, D.F.; Gaines, S.D. Species invasions and extinction: The future of native biodiversity on islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11490–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blowes, S.A.; McGill, B.; Brambilla, V.; Chow, C.F.Y.; Engel, T.; Fontrodona-Eslava, A.; Martins, I.S.; McGlinn, D.; Moyes, F.; Sagouis, A.; et al. Synthesis reveals approximately balanced biotic differentiation and homogenization. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, H.; Cohen, J.E. Communities in patchy environments: A model of disturbance, competition, and heterogeneity. In Ecological Heterogeneity; Kolasa, J., Pickett, S.T.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, L.; Baker, S.C.; Bauhus, J.; Beese, W.J.; Brodie, A.; Kouki, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Lõhmus, A.; Pastur, G.M.; Messier, C. Retention forestry to maintain multifunctional forests: A world perspective. BioScience 2012, 62, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, J.; Salo, K. Forest disturbances affect functional groups of macrofungi in young successional forests: Harvests and fire lead to different fungal assemblages. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 463, 118039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Poff, N.L.; Douglas, M.R.; Douglas, M.E.; Fausch, K.D. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of biotic homogenization. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Poff, N.L. Toward a mechanistic understanding and prediction of biotic homogenization. Am. Nat. 2003, 162, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.; Beisner, B.E. Zooplankton biodiversity and lake trophic state: Explanations invoking resource abundance and distribution. Ecology 2007, 88, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, N.R.; Braghin, L.S.M.; Duré, G.A.V.; Santos, J.S.; Sonoda, S.L.; Bonecker, C.C. Changing taxonomic and functional β-diversity of cladoceran communities in Northeastern and South Brazil. Hydrobiologia 2020, 847, 3845–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Wright, J.P. Disentangling biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning: Deriving solutions to a seemingly insurmountable problem. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodré, E.d.O.; Bozelli, R.L. How planktonic microcrustaceans respond to environment and affect ecosystem: A functional trait perspective. Int. Aquat. Res. 2019, 11, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, E.K.; Wilkinson, G.M. Functional shifts in lake zooplankton communities with hypereutrophication. Freshw. Biol. 2019, 64, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkić, A.G.; Ternjej, I.; Špoljar, M. Hydrology-driven changes in the rotifer trophic structure and implications for food web interactions. Ecohydrology 2018, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Obertegger, U.; Flaim, G. Taxonomic and functional diversity of rotifers, what do they tell us about community assembly? Hydrobiologia 2018, 823, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goździejewska, A.M.; Koszałka, J.; Tandyrak, R.; Grochowska, J.; Parszuto, K. Functional responses of zooplankton communities to depth, trophic status, and ion content in mine pit lakes. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 2699–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, P. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadotte, M.; Albert, C.H.; Walker, S.C. The ecology of differences: Assessing community assembly with trait and evolutionary distances. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goździejewska, A.M.; Gwoździk, M.; Kulesza, S.; Bramowicz, M.; Koszałka, J. Effects of suspended micro- and nanoscale particles on zooplankton functional diversity of drainage system reservoirs at an open-pit mine. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, J.; Prairie, Y.T.; Beisner, B.E. Thermocline deepening and mixing alter zooplankton phenology, biomass and body size in a whole-lake experiment. Freshw. Biol. 2014, 59, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.D.; Simões, N.R.; Meerhoff, M.; Lansac-Tôha, F.A.; Velho, L.F.M.; Bonecker, C.C. Hydrological dynamics drives zooplankton matacommunity structure in a Neotropical floodplain. Hydrobiologia 2016, 781, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, J.; Dias, J.D.; Bonecker, C.C.; Lansac-Tôha, F.A.; Padial, A.A. Importance of temporal variability at different spatial scales for diversity of floodplain aquatic communities. Freshw. Biol. 2016, 61, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.M.A.; Bonecker, C.C. Rotifers in different environments of the Upper Parana River floodplain (Brazil): Richness, abundance and the relationship with connectivity. Hydrobiologia 2004, 522, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöll, K.; Kiss, A.; Dinka, M.; Berczik, A. Flood-Pulse effects on zooplankton assemblages in a river-floodplain system (Gemenc Floodplain of the Danube, Hungary). Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 2012, 97, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Ralph, T.J.; Ryder, D.S.; Hunter, S.J.; Shiel, R.J.; Segers, H. Spatial dissimilarities in plankton structure and function during flood pulses in a semi-arid floodplain wetland system. Hydrobiologia 2015, 747, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M.J.; Paver, S.F.; Dungey, K.E.; Velho, L.F.M.; Kent, A.D.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Kellerhals, D.M.; Randle, M.R. Diversity and succession of pelagic microorganisms communities in a newly restored Illinois River floodplain lake. Hydrobiologia 2017, 804, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, T.; Baranyi, C.; Reckendorfer, W.; Schimer, F. The impact of surface water exchange on the nutrient and particle dynamics in side-arms along the River Danube, Austria. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 328, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasten, J. Innundation and isolation: Dynamics of phytoplankton communities in seasonal inundated flood plain waters of the Lower Odra Valley National Park—Northeast Germany. Limnologica 2003, 33, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiler, G.; Hein, T.; Schiemer, F. The significance of hydrological connectivity for limnological processes in Danubian backwaters. Verhandlungen Des Int. Ver. Limnol. 1994, 25, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyás, P. Tägliche Zooplankton Untersuchungen im Donau-Nebenarm bei Ásványráró im Sommer 1985. Wissenschaftliche Kurzreferate, 26; Arbeitstagung der IAD: Passau, Deutschland, 14–18 September 1987; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gulyás, P. Studies on Rotatoria and Crustacea in the various water-bodies of Szigetköz. Limnol. Aktuelle 1994, 2, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bothár, A.; Ráth, B. Abundance dynamics of Crustacea in different littoral biotopes of the “Szigetköz” side arm system, River Danube, Hungary. Verhandlungen Des Int. Ver. Limnol. 1994, 25, 1684–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Vranovský, M. Zooplankton of two side arms of the Danube at Baka (1820.5–1822.5 river km). Work. Inst. Fish. Res. Hydrobiol. 1985, 5, 47–100. [Google Scholar]

- Vranovský, M. Zooplankton of the Danube side arm under regulated ichthyocoenosis conditions. Verhandlungen Des Int. Ver. Limnol. 1991, 24, 2505–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranovský, M. Impact of the Gabčíkovo hydropower plant operation on planktonic copepod assemblages in the River Danube and its floodplain downstream of Bratislava. Hydrobiologia 1997, 347, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illyová, M. Cladoceran taxocoenoses in the territory affected by the Gabčíkovo barrage system. Biologia 1996, 51, 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- Illyová, M. Planktonic crustaceans (Crustacea) in the littoral zone of the Danube inland delta (r km 1841–1804). Folia Faun. Slovaca 1998, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Illyová, M.; Némethová, D. Long-term changes in cladoceran assemblage in the Danube floodplain area (Slovak–Hungarian stretch). Limnologica 2005, 35, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Illyová, M.; Matečný, I. Ecological validity of river-floodplain system assessment by planktonic crustacean survey (Branchiata: Branchiopoda). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 4195–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illyová, M.; Beracko, P.; Vranovský, M.; Matečný, I. Long-term changes in copepod assemblages in the area of the Danube floodplain (Slovak–Hungarian stretch). Limnologica 2017, 65, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waringer, J.; Chovanec, A.; Straif, M.; Graf, W.; Reckendorfer, W.; Waringer-Löschenkohl, A.; Waidbacher, H.; Schultz, H. The Floodplain Index—Habitat values and indication weights for molluscs, dragonflies, caddisflies, amphibians and fish from Austrian Danube floodplain waterbodies. Lauterbornia 2005, 54, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mucha, I. (Ed.) Gabčíkovo Part of the Hydroelectric Power Project Environmental Impact Review (Evaluation Based on Two Year Monitoring); Comenius University: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1995. Available online: http://www.gabcikovo.gov.sk/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Mack, H.R.; Conroy, J.D.; Blocksom, K.A.; Stein, R.A.; Ludsin, S.A. A comparative analysis of zooplankton field collection and sample enumeration methods. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2012, 10, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, L.A.; Rybak, J.I. (Eds.) Freshwater Crustacean Zooplankton of Europe: Cladocera & Copepoda (Calanoida, Cyclopoida). Key to Species Identification, with Notes on Ecology, Distribution, Methods and Introduction to Data Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. XV–918. [Google Scholar]

- Šrámek-Hušek, R. Naši klanonožci; Nakladetelstí ČSAV: Praha, Československo, 1953; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dussart, B.H.; Defaye, D. Copepoda: Introduction to the Copepoda; SPB Academic Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; The Hague, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 1–277. [Google Scholar]

- Janetzky, W.; Enderle, R.; Noodt, W. Crustacea: Copepoda: Gelyelloida und Harpacticoida. In Süsswasserfauna von Mitteleuropa; Schwoerbel, J., Zwick, P., Eds.; Gustav Fischer Verlag, Bd.: Stuttgart, Germany, 1996; Volume 8, pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Přikryl, I.; Bláha, M. Klíče středoevropských Cyclopidae a Diaptomidae (bez druhů podzemních vod). Unpublished work.

- Amoros, C. Introduction pratique à la systématique des organismes des eaux continentales françaises—5. Crustacés cladocères. Publ. De La Société Linnéenne De Lyon 1984, 53, 72–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gulyás, P.; Forró, L. Az ágascsápú rárok (Cladocera) kishatározója; Környezetgazdálkodási Intézet (KGI): Budapest, Hungary, 1999; pp. 1–237. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon 1972, 21, 213–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E.; Dornelas, M.; Moyes, F.; Gotelli, N.J.; McGill, B. Rapid biotic homogenization of marine fish assemblages. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleff, P.; Gaston, K.J.; Lennon, J.J. Measuring beta diversity for presence–absence data. J. Anim. Ecol. 2003, 72, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberté, E.; Legendre, P. A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 2010, 91, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, I. Fauna Slovenska III—Anomopoda, Ctenopoda, Haplopoda, Onychopoda (Crustacea: Branchiopoda); VEDA: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010; p. 496. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilko, D.E.; Shurganova, G.V.; Kudrin, I.A.; Yakimov, B.N. Identification of freshwater zooplankton functional groups based on the functional traits of species. Povolzhskiy J. Ecol. 2020, 3, 290–306. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package, R package version 2.6-4; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté, E.; Legendre, P.; Shipley, B. FD: Measuring Functional Diversity from Multiple traits, and Other Tools for Functional Ecology; R package version 1.0-12.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A. The ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A. Long-term changes of Crustacean (Cladocera, Ostracoda, Copepoda) assemblages in Szigetkoz Floodplain Area (Hungary) 1991–2002. Int. Assoc. Danub. Res. 2004, 35, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schöll, K.; Kiss, A. Spatial and temporal distribution patterns of zooplankton assemblages (Rotifera, Cladocera, Copepoda) in the water bodies of the Gemenc Floodplain (Duna-Dráva National Park, Hungary). Opusc. Zool. Bp. 2008, 39, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, A.; Schöll, K. Checklist of the Crustacea (Cladocera, Ostracoda, Copepoda) fauna in the active floodplain area of the Danube (1843–1806, 1669 and 1437–1489 rkm). Opusc. Zool. Bp. 2009, 40, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, A.; Ágoston-Szabó, E.; Dinka, M.; Schöll, K.; Berczik, Á. Microcrustacean (Cladocera, Copepoda, Ostracoda) diversity in three side arms in the Gemenc floodplain (Danube River, Hungary) in different hydrological situations. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2014, 7, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kazakov, S.; Schöll, K.; Kalchev, R.; Pehlivanov, L.; Kiss, A. Comparison of zooplankton species diversity in Hungarian and Bulgarian Danube sections. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2014, 7, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Community (CEC). Working Group Report of Variant C of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Project; Commission of the European Community, Czech and Slovak Federative Republic, Republic of Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, C.M.; Freeman, M.C.; Freeman, B.J. Regional effects of hydrological alterations on riverine macrobiota in the new world: Tropical temperate comparisons. BioScience 2000, 50, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J.; Bayley, P.B.; Sparks, R.E. The flood-pulse concept in river-floodplain systems. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. Spec. Publ. 1989, 106, 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bothár, A. Qualitative und quantitative Planktonuntersuchungen in der Donau bei God/Ungarn (1969 Strom km) II. Zooplankton 30; Arbeitstagung der IAD: Dubendorf, Switzerland, 1994; pp. 4–144. [Google Scholar]

- Štifter, P. A review of the genus Ilyocryptus (Crustacea, Anomopoda) from Europe. Hydrobiologia 1991, 225, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natho, S.; Tschikof, M.; Bondar-Kunze, E.; Hein, T. Modelling the effect of enhanced lateral connectivity on nutrient retention capacity in large river floodplains: How much connected floodplain do we need? Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beracko, P.; Kubalová, S.; Matečný, I. Aquatic macrophyte dynamics in the Danube Inland Delta over the past two decades: Homogenisation or differentiation of taxonomic and functional community composition? Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, H.J.; Negrea, S. A conspectus of the Cladocera of the subterranean waters of the world. Hydrobiologia 1996, 325, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illyová, M.; Némethová, D. Littoral cladoceran and copepod (Crustacea) fauna in the Danube and Morava river floodplains. Biologia 2002, 57, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Hudec, I. Origin and penetrating ways of cladocerans (Crustacea, Branchiopoda) in Slovakia. Ochr. Prírody 1998, 16, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Goździejewska, A.; Glińska-Lewczuk, K.; Obolewski, K.; Grzybowski, M.; Kujawa, R.; Lew, S.; Grabowska, M. Effects of lateral connectivity on zooplankton community structure in floodplain lakes. Hydrobiologia 2016, 774, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, G.; O’Farrell, I.; Hein, T. Hydrological conditions determine shifts of plankton metacommunity structure in riverine floodplains without affecting patterns of species richness along connectivity gradients. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 85, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.V.; Tockner, K. Biodiversity: Towards a unifying theme for river ecology. Freshw. Biol. 2001, 46, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napiórkowski, P.; Bakowska, M.; Mrozińska, N.; Szymańska, M.; Kolarova, N.; Obolewski, K. The Effect of Hydrological Connectivity on theZooplankton Structure in Floodplain Lakes of aRegulated Large River (the Lower Vistula, Poland). Water 2019, 11, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galir, A.; Stević, F.; Čmelar, K.; Špoljarić Maronić, D.; Žuna Pfeiffer, T.; Bek, N. A Decade of Change in the Floodplain Lake: Does Zooplankton Yield or Resist? Water 2025, 17, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Jeong, K.S.; Kim, S.K.; La, G.H.; Chang, K.H.; Joo, G.J. Role of macrophytes as microhabitats for zooplankton community in lentic freshwater ecosystems of South Korea. Ecol. Inform. 2014, 24, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaz, S.M.; Bini, L.M.; Bozelli, M. Floods increase similarity among aquatic habitats in river-floodplain systems. Hydrobiologia 2007, 579, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, F.W.B.; Van Katwijk, M.M.; Van der Velde, G. Impact of hydrology on phyto- and zooplankton community composition in floodplain lakes along the Lower Rhine and Meuse. J. Plankton Res. 1994, 16, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Designation | Site Name | Coordinates (Word Geodetic System—WGS84) | Danube River Kilometers | Biotop | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Longitude | ||||

| L6e | Dunajské kriviny | 47.988222° N | 17.342472° E | 1840.5 | Eupotamal |

| L14e | Gabčíkovo | 47.861306° N | 17.533917° E | 1817.5 | Eupotamal |

| L9pa | Bodíky gate | 47.921194° N | 17.445028° E | 1830 | Parapotamal |

| L14pa | Istragov | 47.827525° N | 17.561027° E | 1816 | Parapotamal |

| L10pl | Kráľovská lúka | 47.903667° N | 17.487972° E | 1825 | Plesiopotamal |

| L18pl | Sporná sihoť | 47.787194° N | 17.677417° E | 1804.5 | Plesiopotamal |

| Sites | Mean Species Richness | Maximal Species Richness | Minimal Species Richness | Trend Line (Within-Site Temporal Change in Species Richness) | Adjusted R2 (%) | Akaike Information Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L6e | 9.2 | 15 | 5 | cubic | 50.25 | 134.37 |

| L14e | 8.4 | 16 | 4 | cubic | 48.98 | 145,49 |

| L9pa | 13.1 | 18 | 9 | cubic | 30.17 | 137.31 |

| L14pa | 13 | 18 | 8 | cubic | 18.42 | 150.76 |

| L10pl | 14.6 | 18 | 11 | quadratic | 20.12 | 129.89 |

| L18pl | 12.1 | 17 | 8 | quadratic | 12.94 | 136.04 |

| Totally | 23.3 | 29 | 17 | cubic | 39.77 | 136.63 |

| Sites | Mean Species Richness | Maximal Species Richness | Minimal Species Richness | Trend Line (Within-Site Temporal Change in Species Richness) | Adjusted R2 (%) | Akaike Information Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L6e | 12.8 | 20 | 5 | quadratic | 37.33 | 158.56 |

| L14e | 9.1 | 16 | 4 | quadratic | 37.93 | 138.33 |

| L9pa | 20.4 | 28 | 10 | quadratic | 71.36 | 155.99 |

| L14pa | 19.2 | 30 | 4 | quadratic | 66.43 | 168.68 |

| L10pl | 19.7 | 31 | 11 | quadratic | 51.59 | 177.41 |

| L18pl | 15.3 | 24 | 7 | quadratic | 51.34 | 160.71 |

| Totally | 38.5 | 50 | 20 | quadratic | 75.09 | 176.23 |

| Sites | Mean Functional Dispersion | Maximal Functional Dispersion | Minimal Functional Dispersion | Trend Line (Within-Site Temporal Change in Functional Dispersion) | Adjusted R2 (%) | Akaike Information Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L6e | 2.33 | 3.06 | 1.42 | cubic | 21.67 | 32.93 |

| L14e | 2.67 | 3.12 | 1.76 | linear | 0.03 | 27.07 |

| L9pa | 2.36 | 3.29 | 1.11 | cubic | 63.26 | 30.36 |

| L14pa | 2.43 | 3.27 | 1.36 | linear | 2.07 | 43.68 |

| L10pl | 2.5 | 3.06 | 1.9 | linear | 7.67 | 5.29 |

| L18pl | 2.26 | 2.83 | 1.54 | linear | 2.09 | 21.06 |

| Totally | 3.04 | 3.44 | 2.72 | linear | 42.19 | −33.34 |

| Sites | Mean Functional Dispersion | Maximal Functional Dispersion | Minimal Functional Dispersion | Trend Line (Within-Site Temporal Change in Functional Dispersion) | Adjusted R2 (%) | Akaike Information Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L6e | 2.33 | 3.19 | 0.81 | quadratic | 36.00 | 49.03 |

| L14e | 2.01 | 2.69 | 0.35 | cubic | 20.14 | 45.80 |

| L9pa | 1.79 | 2.41 | 1.03 | linear | 3.88 | 30.29 |

| L14pa | 2.24 | 2.87 | 1.12 | linear | 2.32 | 41.32 |

| L10pl | 2.2 | 2.53 | 1.36 | quadratic | 7.59 | 11.42 |

| L18pl | 2.35 | 2.67 | 1.83 | cubic | 24.19 | −18.70 |

| Totally | 2.25 | 2.89 | 1.81 | cubic | 19.9 | −9.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beracko, P.; Kokavec, I.; Matečný, I. Long-Term Responses of Crustacean Zooplankton to Hydrological Alterations in the Danube Inland Delta: Patterns of Biotic Homogenization and Differentiation. Diversity 2025, 17, 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17100670

Beracko P, Kokavec I, Matečný I. Long-Term Responses of Crustacean Zooplankton to Hydrological Alterations in the Danube Inland Delta: Patterns of Biotic Homogenization and Differentiation. Diversity. 2025; 17(10):670. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17100670

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeracko, Pavel, Igor Kokavec, and Igor Matečný. 2025. "Long-Term Responses of Crustacean Zooplankton to Hydrological Alterations in the Danube Inland Delta: Patterns of Biotic Homogenization and Differentiation" Diversity 17, no. 10: 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17100670

APA StyleBeracko, P., Kokavec, I., & Matečný, I. (2025). Long-Term Responses of Crustacean Zooplankton to Hydrological Alterations in the Danube Inland Delta: Patterns of Biotic Homogenization and Differentiation. Diversity, 17(10), 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17100670