Rethinking Urban Lawns: Rewilding and Other Nature-Based Alternatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- To extend the conceptual framework established earlier [2] toward the practical requirements for implementing nature-based strategies for urban lawns;

- (b)

- To analyse selected case studies in Europe and Asia, complemented by insights from the literature review, in order to develop a comprehensive typology of NBS related to urban lawns, and identify barriers and opportunities for their implementation in diverse urban contexts;

- (c)

- To formulate practical recommendations and a future research direction for promoting NBS alternatives to conventional lawns, including rewilding, to enhance ecological performance, social acceptance, and management adaptability.

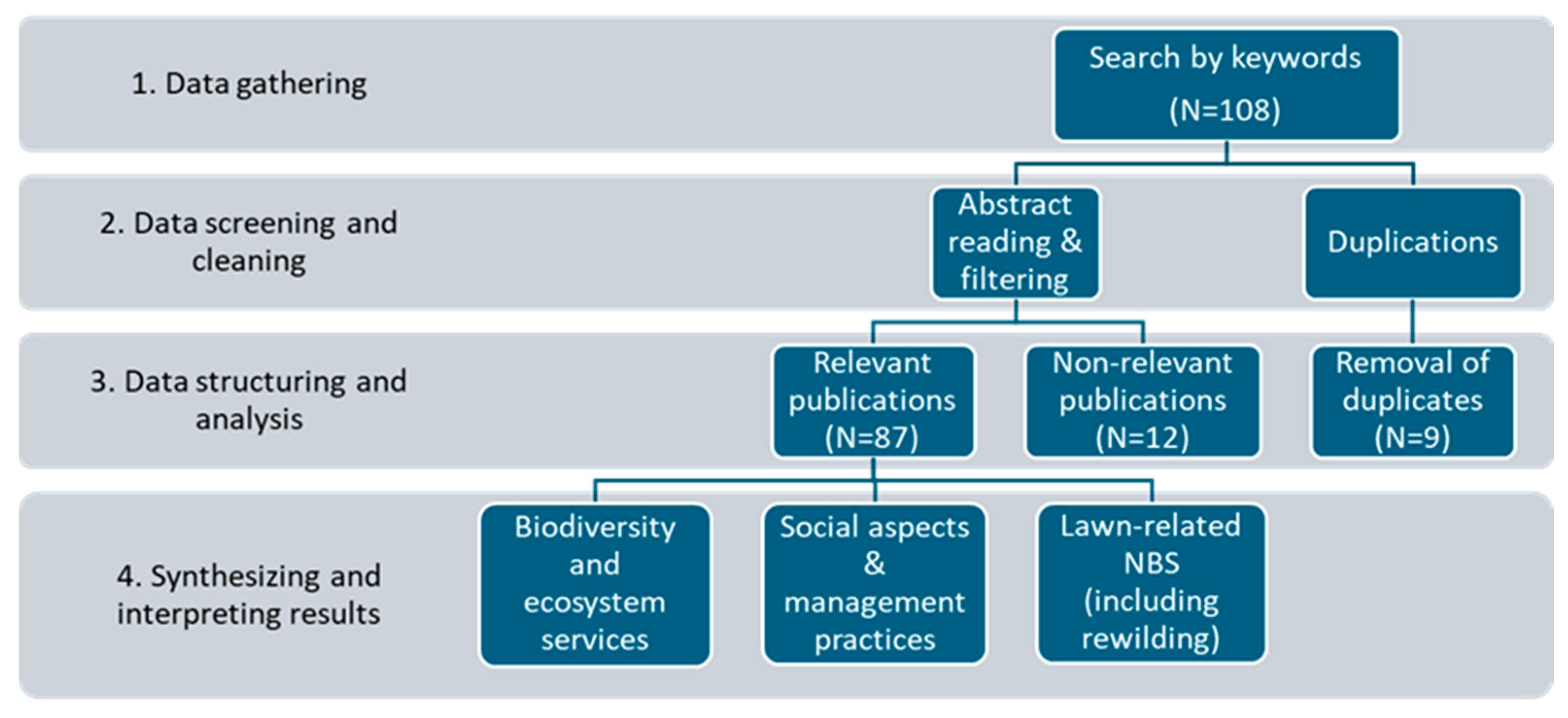

2. Materials and Methods

- Phase 1: Conceptual grounding—conduct a focused narrative review of existing literature to elaborate on the key aspects of lawn research, such as: (a) biodiversity, (b) ecosystem services and ecosystem disservices, (c) public perception, attitude, and preferences, and (d) NBS-related lawn alternatives to identify conceptual and practical gaps.

- Phase 2: Case study analysis—examine ten selected case studies representing various perspectives of lawn research to investigate how they appear in practice, highlighting challenges and opportunities, while linking findings back to the literature to reinforce the theoretical foundation.

- Phase 3: Recommendations for practical application and future research to support the integration of the nature-based lawn alternatives (including rewilding) into the planning, design, and management of UGS.

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Case Study

- (1)

- Conventional lawns (taking the biggest area in the cities, common for most UGS), which are cut on average 8–12 times per season (or more) to a height of 3–4–10 cm according to the official municipal standards; with remaining the clipping on the area and mulching.

- (2)

- Sports lawns (e.g., football fields), which are typically subject to more intensive management. They occupy the UGS of sports facilities and account for only a small proportion of the total urban lawn area.

- (3)

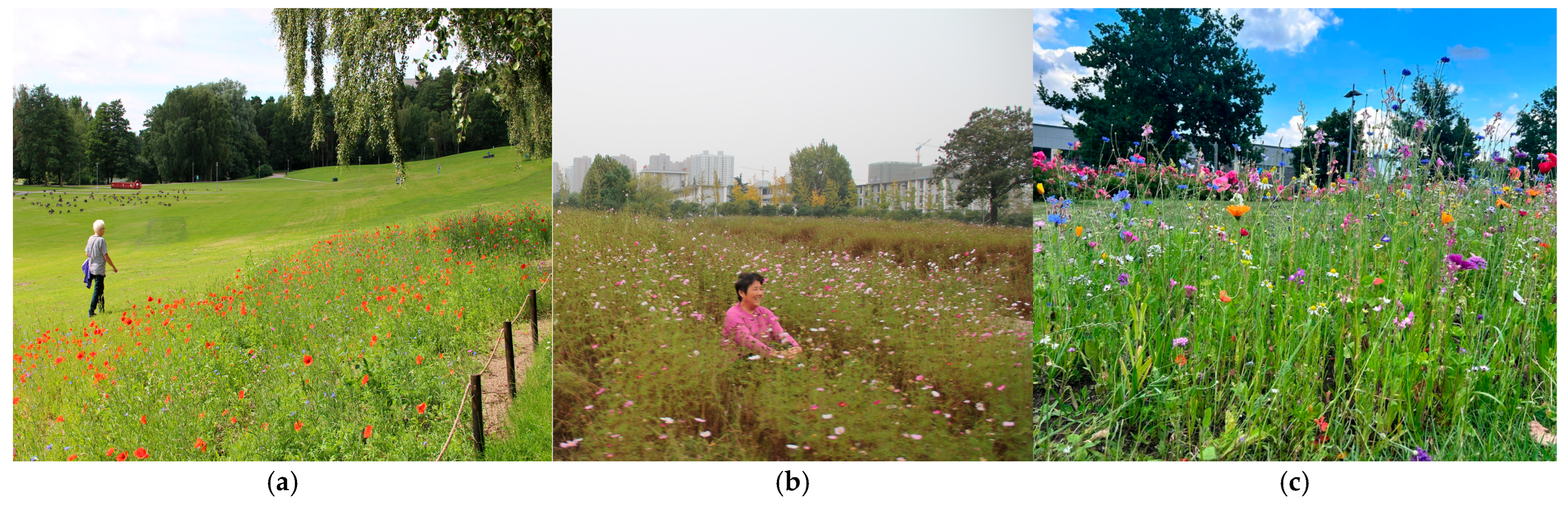

- Meadow-like lawns, representing a lawn alternative, which are mowed one to three times per season, and the clippings removed. In European cities (especially German and Swedish), there is a rise in using this type of lawn not only in public parks, but also in other types of UGS, including private gardens, and road embankments inside or on the outskirts of cities.

- (4)

- Other sustainable lawn alternatives (e.g., permaculture or edible lawns, naturalistic herbaceous plantings, grass-free lawns, lawns comprised exclusively of locally native species, pictorial meadows, and rewilding-oriented lawns) designed to reduce resource inputs and maintenance (mowing once or twice per season or not mowing at all) while enhancing biodiversity, ecosystem services, and habitat quality for urban wildlife (mostly insects); they are increasingly implemented in public parks, institutional landscapes (e.g., university campuses), and experimental urban sites.

2.3. Recommendations for Practical Application

3. Results

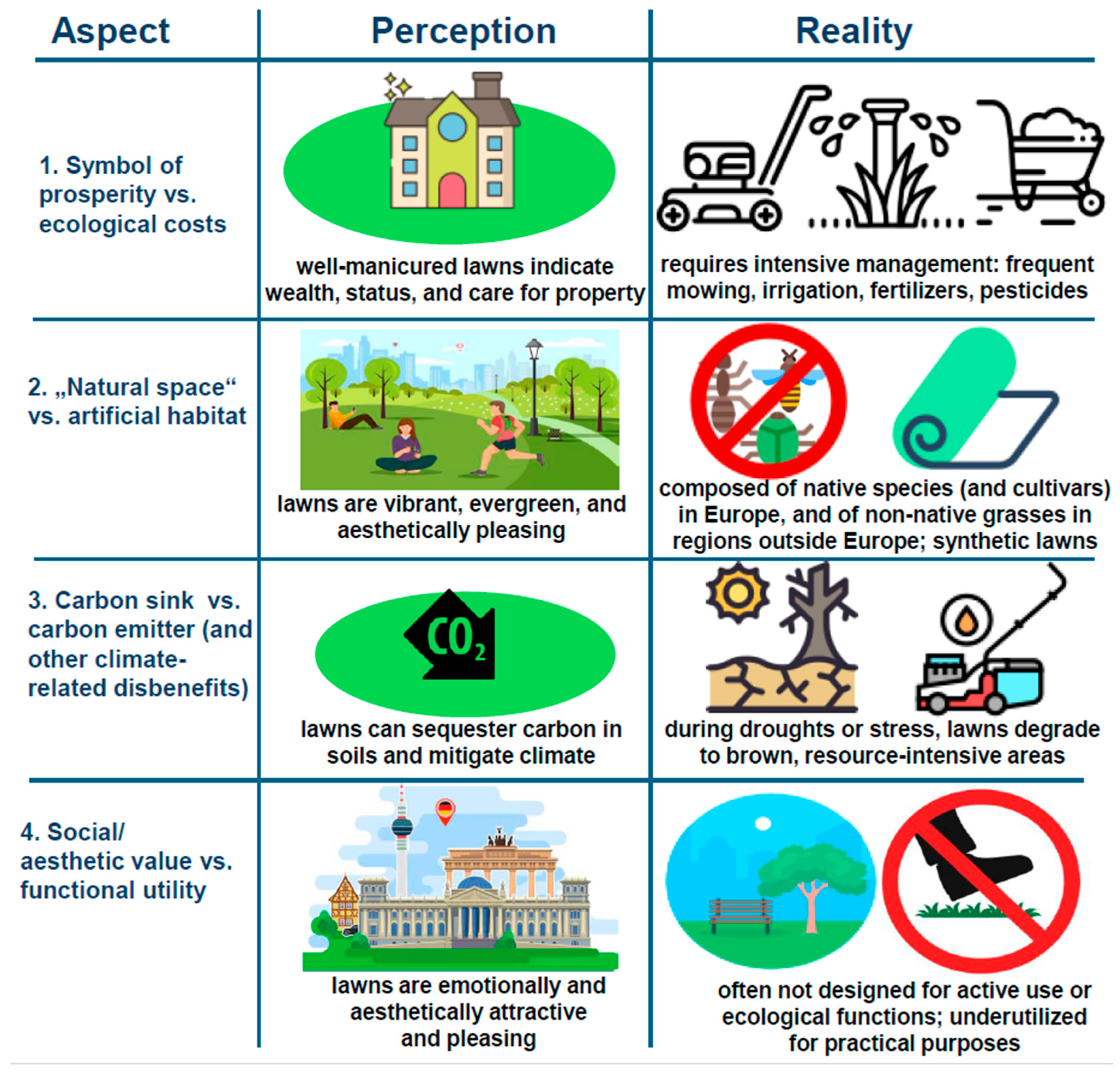

3.1. Lawn as a Contradictory Phenomenon

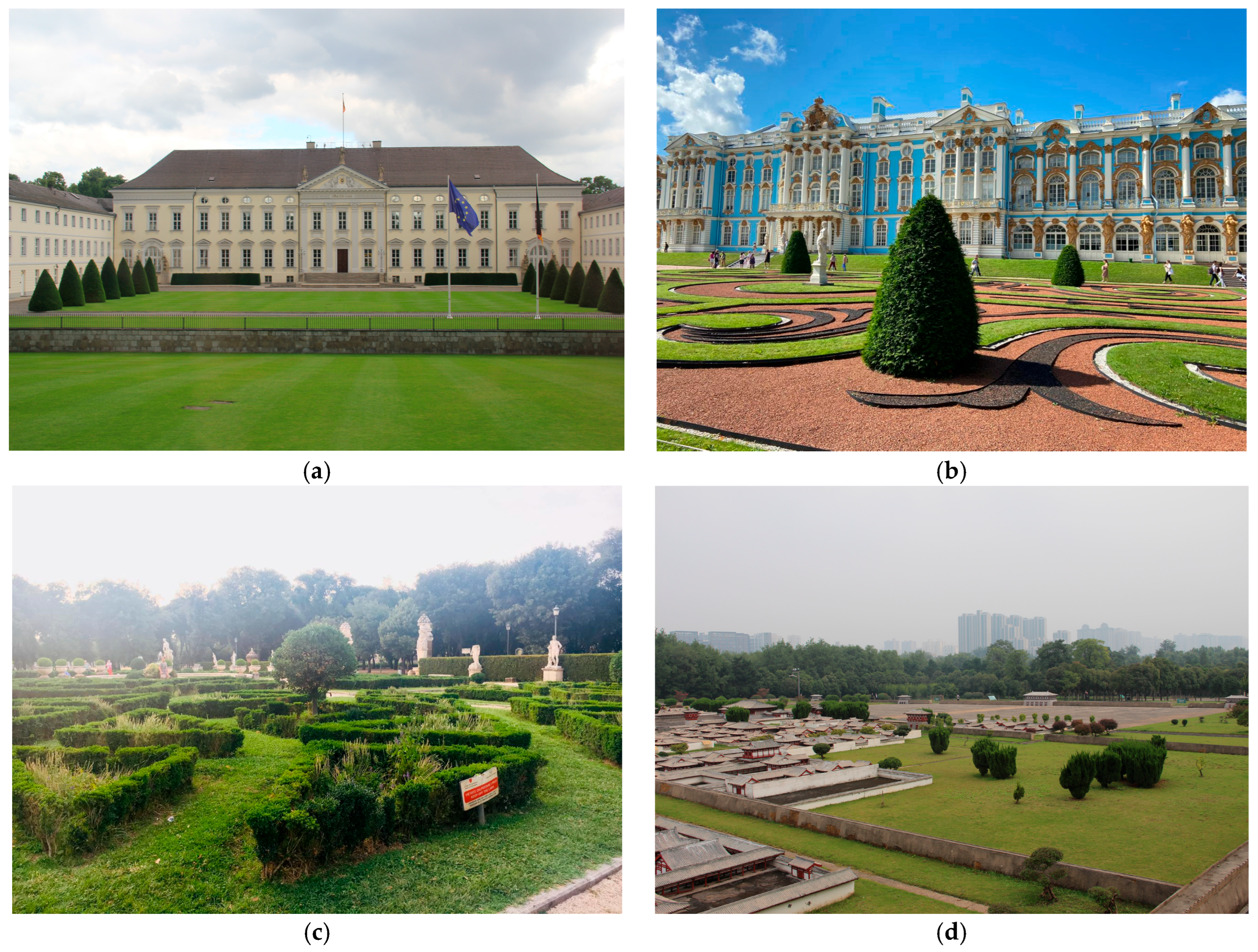

3.1.1. Symbol of Prosperity Versus High Ecosystem Disservices and Maintenance Costs

3.1.2. “Natural” Space Versus Artificial Habitat and Homogenization

3.1.3. Green Space Versus a “Brownscape”

3.1.4. Social and Emotional Value Versus Functional Utility

3.2. Integrating Contradictions: Toward Sustainable Alternatives (NBS) and Rewilding for Urban Lawns

3.2.1. Rationale and Benefits of NBS for Urban Lawns

3.2.2. Typology of NBS for Urban Lawns

- (1)

- Urban semi-natural grasslands retain a close-to-natural or semi-natural composition, often resulting from historical land use such as traditional farming practices (pastures and meadows) rather than intensive management, where grasses and forbs thrive together, providing valuable benefits for people and wildlife through essential ecosystem services. They often include remnants of older grasslands, which are mainly found in old parks like landscape gardens [136], where, before the introduction of the motorized lawn mower in the 1950th, such grasslands were used as pastures and meadows. Further examples can be found in urban parks, road verges, and other green spaces, including Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin (former airport area), Adlershof district in Berlin, and Lene-Voigt Park (former railway station) in Leipzig. Additional examples are provided by interventions within the peri-urban grassland/floodplain restoration projects in Leipzig, including Auwald (Riverside/Floodplain Forest), as well as the metropolitan grassland biodiversity program and Appia Antica Regional Park in Rome (Figure 9).

- (2)

- Rewilded lawns (spontaneous urban vegetation) are represented by areas where largely unmanaged or self-establishing (naturally or spontaneously growing) vegetation, which is not intentionally planted and cultivated by humans. They create more natural, species-rich covers. Our studies found that in Western, Northern (and recently in Eastern) Europe, the “go wild” approach is popular (e.g., Park Gleisdreieck in Berlin), whereas in China, Vietnam, and Russia, a balance is needed between the wild, variable, species-rich qualities of spontaneous vegetation (which can be seen as messy) and a better-kept lawn appearance (Figure 10). Hence, a managed mixed lawn using a “cues to care” approach of Nassauer [137] may be more successful than relying solely on entirely spontaneous growth.

- (3)

- Urban species-rich perennial meadows (meadow-like lawns and grass-free tapestry lawns) use appropriate native perennial species to form dense, low-growing covers that need little mowing. They can be created by sowing seeds or planting pre-grown plugs—the faster but costlier option. Seeded lawns take longer to fill in, and some grasses may eventually return. Once established, they need minimal maintenance and can be walked on, though people often avoid stepping on the flowers. Examples include urban meadows within the projects on adaptive planting to enhance biodiversity and cope with climate change, and to design and manage meadow-like plant communities, where wildflower species play a significant role (but grasses can still be the foundation for such meadows) in city districts of Barcelona, Beijing, and Moscow. Also, they are promoted within the Parks programme and projects on restoration of species-rich flowering meadows (Blühwiesen) in Berlin (e.g., Park Gleisdreieck) and Leipzig (e.g., Johanna Park, Friedenspark), several kindergartens of Leipzig, as well as at the campuses of the UFZ and the Uppsala and Stockholm Universities. Grass-free/tapestry lawns, which are made from planted low-growing flowering perennial and annual species but without any grasses and cut once a season, are closely related to this category (e.g., SLU campus in Uppsala) (Figure 11).

- (4)

- Naturalistic mixed-herbaceous plantings—an approach proposed by Dunnett and Hitchmough [138] that combines native herbaceous (perennials, including bulbs) and grass species with attractive non-native, flowering prairie plants and low-growing shrubs depending on climate (e.g., xerophyte species). The primary goal of this type was addressing biodiversity needs (attract pollinators) and the preference of urban citizens to bright, pretty flowers that could reinforce the aesthetic acceptance of alternative solutions. Among the examples are interventions within Barcelona’s naturalisation Program and Superblocks Program, including greening the streets, reclaiming of inner blocks, and establishing green corridors with naturalistic mixed-herbaceous plantings with grasses and perennials, wildflower meadows in the Citadelle park. Many large naturalistic perennial plantings are found in Moscow at Krymskaya Embankment, Triumphalnaya Square, and Park Muzeon. Planting with native and non-native species in a more naturalistic style is detected in public parks of St. Petersburg, Leipzig, Berlin, and Xi’an, including the Botanical Garden areas. Greening with perennial plantings is typical for the campuses of the Uppsala and Stockholm Universities (Figure 12). This type is quite diverse and reflects the specifics of local perennial plants’ availability in nurseries. This type is perhaps one of the most “horticultural” types that can include more maintenance operations compared to other, more “nature” driven types.

- (5)

- Mixed-vegetation groundcovers are low-growing plant assemblages (grasses, forbs, and herbs) designed to replace conventional lawns in some particular parts of urban green spaces. They provide continuous ground cover, often similar in appearance to uniform lawns, while enhancing biodiversity, providing pollinator habitat, and protecting soils. Case studies in Moscow and St. Petersburg show the shift of public preference for a mix of cultivated and spontaneous plants, highlighting that the success of groundcovers depends on balancing ecological aesthetics with public perception of “wildness” and maintenance. Plant composition varies depending on climatic conditions—northern cities such as Uppsala, Stockholm, and St. Petersburg, as well as Moscow, tend to use low-growing perennial groundcover species. In contrast, Barcelona and Rome favour mixed-vegetation groundcovers using drought-tolerant Mediterranean groundcovers. In Chinese cities, shade-tolerant native species are used, e.g., in demonstration gardens on the Xi’an University campus (Figure 13).

- (6)

- Edible lawn alternatives are based on plants such as creeping herbs (e.g., thyme, oregano), strawberries, vegetables, low-growing fruit plants, and certain clovers that can be grown as a ground cover. Being part of the broader edible landscape concept, they provide a functional, sustainable, and often scented/aromatic alternative to traditional grass, attract pollinators, and produce food. Examples are found in community gardens, residential courtyards, and public green spaces in Leipzig and Berlin, but are not yet widely adopted in Swedish, Vietnamese, and Chinese cities (except for the Xi’an University campus and within the roof garden of the GreenCityLabHuế project). However, edible lawns are emerging in Moscow and St. Petersburg through urban gardening initiatives that combine edible and ornamental plants in residential/blocks’ green areas, street verges, and flowerbeds, creating a mix of aesthetic appeal and functional food production (Figure 14).

- (7)

- Pictorial (annual) meadows are created from native and exotic annual plants, providing colourful flowering sites that are also highly attractive to wildlife. They are found on university campuses and public parks in Stockholm and Uppsala. In Berlin and Leipzig, pictorial and wildflower meadow pilots have been implemented as part of municipal greening campaigns. In Germany, such meadows are often called Blühwiesen (the same as urban species-rich meadows—type 1) (Figure 15).

| Type of Alternative | Primary Goals | Other Co-Benefits | Design, Plant Composition, and Maintenance | Case Study | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Urban semi-natural grasslands (Figure 9) | Ecological (support original flora/fauna (pollinators)) | Carbon sequestration, erosion control | Remnants of historically natural or semi-natural grasslands, or areas managed to mimic them. Rich variety of native wildflowers and grasses that developed over time. Mowing once or twice per year or grazing; no irrigation; adaptive to local soil and climate | Leipzig, Rome, Berlin | [34,38,39,81,83,95,131,136,139,140] |

| (2) Rewilded lawns (spontaneous urban vegetation) (Figure 10) | Biodiversity restoration, ecosystem service enhancement | Carbon sequestration, microhabitats for insects and birds, and aesthetic variation | Mixture of spontaneously appearing native and exotic plants. Minimal human intervention; occasional control of aggressive weeds that could also become invasive; supports ecological succession | Leipzig, Berlin | [2,37,40,45,72,73,74,76,87,125,141,142] |

| (3) Urban species-rich meadows (meadows-like lawns) (Figure 11) | Biodiversity enhancement (incl. pollinator support), habitat provision | Aesthetic value, seasonal floral diversity | Intentionally planted or managed to have a high diversity of flowering plants, grasses, and other species. High content of flowering perennial plants. Composition and structure differ depending on the availability of soil nutrients, water, and mowing regime. Mowing once or twice per year; minimal irrigation; adaptive to local soil and climate | Barcelona, Beijing, Berlin, Leipzig, Moscow, Stockholm, Uppsala | [44,45,48,49,53,82,98,107,114,131,139,143,144,145] |

| (4) Naturalistic herbaceous perennial plantings (Figure 12) | Biodiversity and aesthetic value | Could include Nitrogen-fixing species, pest control | Plant communities made from perennial grasses and forbs, native as well as some exotics. Low to medium maintenance; requires initial planting and occasional weeding | Berlin, Leipzig, Moscow, St.-Petersburg, Stockholm, Xi’an, Uppsala. | [2,6,43,48] |

| (5) Mixed-vegetation ground covers (Figure 13) | Soil protection, multifunctionality | Microclimate regulation, runoff reduction, visual diversity | Low maintenance, drought- or shade-tolerant ground-cover species; include diversity of species with decorative characteristics (diversity of colour, texture and forms). Minimal irrigation and occasional weeding | Leipzig, Berlin, Moscow, St.-Petersburg, Uppsala, Xi’an | [11,48,51] |

| (6) Edible lawn alternatives (Figure 14) | Food production and multifunctionality | Pollinator habitat, soil health, urban microclimate benefits | Often permaculture-inspired: low or no mowing, diverse edible species; some irrigation may be needed; maintenance depends on species selection | Berlin, Leipzig, Moscow, St. Petersburg | [11,51,57,133] |

| (7) Pictorial (annual) meadows (Figure 15) | Pollinator habitat, decorative purpose (colourful, designed meadow) | Visual diversity, runoff reduction | Made from native and exotic annual plants. Occasional weeding. Cut at the end of the season and reseed in the next year | Berlin, Leipzig, Stockholm, Xi’an, Uppsala | [1,48] |

3.2.3. Implementation Methods and Practical Considerations

- Selecting appropriate sites;

- Reducing management intensity;

- Planting native species;

- Engaging local communities in the planting and maintenance process;

- Applying adaptive management (e.g., research-based time of mowing aiming to achieve the best flowering effect and attract different groups of pollinators during the vegetative season).

4. Discussion

4.1. Urban Lawns Reconsidered

4.2. Nexus Between NBS, Rewilding, and Other Sustainable Alternatives for Urban Lawns

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

- Conducting longitudinal studies to assess ecological and social outcomes of alternative lawns over multiple seasons and years.

- Expanding comparative analyses to cities outside Eurasia, including arid, tropical, and subtropical regions, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere, using similar methodologies.

- Evaluating cost-effectiveness and scalability of nature-based and rewilding interventions.

- Integrating multi-disciplinary approaches, combining ecology, landscape architecture, urban planning, and social sciences to bridge theory and practical implementation.

- Adopting a transdisciplinary approach for investigating and achieving socio-cultural acceptance of diverse lawn alternatives and for extending strategies for community engagement, co-design, and environmental education.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hedblom, M.; Lindberg, F.; Vogel, E.; Wissman, J.; Ahrné, K. Estimating urban lawn cover in space and time: Case studies in three Swedish cities. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Haase, D.; Dushkova, D.; Haase, A. Lawns in Cities: From a Globalised Urban Green Space Phenomenon to Sustainable Nature-Based Solutions. Land 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knot, P.; Hrabe, F.; Hejduk, S.; Skladanka, J.; Kvasnovsky, M.; Hodulikova, L.; Caslavova, I.; Horky, P. The impacts of different management practices on botanical composition, quality, colour, and growth of urban lawns. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 26, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ignatieva, M.; Larsson, A.; Zhang, S.; Ni, N. Public perceptions and preferences regarding lawns and their alternatives in China: A case study of Xi’an. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Nielsen, S.; Martin, D.J. Recognising lawns as a part of “designed nature”: Pioneering study of lawn’s plant biodiversity in Australian context. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; States, S.L. Urban green spaces and sustainability: Exploring the ecosystem services and disservices of grassy lawns versus floral meadows. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Koda, E.; Červenková, J.; Děkanovský, I.; Nowysz, A.; Mazur, Ł.; Jakimiuk, A.; Vaverková, M.D. Green space in an extremely exposed part of the city center “Aorta of Warsaw”—Case study of the urban lawn. Urban Ecosyst. 2023, 26, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Ahrné, K.; Wissman, J.; Stewart, G.H. Urban lawns and their multifunctionality. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 610529. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, M.R. Urban lawns as nature-based learning spaces. Ecopsychology 2022, 14, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Casagrande, D.; Harlan, S.L.; Yabiku, S.T. Residents’ yard choices and rationales in a desert city: Social priorities, ecological impacts, and decision tradeoffs. Environ. Manag. 2016, 58, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.A. Ecosystem services from turfgrass landscapes. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 26, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Song, J. Cooling and energy saving potentials of shade trees and urban lawns in a desert city. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Pasternak, G.; Sas, W.; Hurajová, E.; Koda, E.; Vaverková, M.D. Nature-Based Management of Lawns—Enhancing Biodiversity in Urban Green Infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halik, Ü. Stadtbegrünung im Ariden Milieu: Das Beispiel der Oasenstädte des Südlichen Xinjiang/VR China, Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung Ökologischer, Sozioökonomischer und Kulturhistorischer Aspekte. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hartin, J.S.; Surls, R.A.; Bush, J.P. Lawn removal motivation, satisfaction, and landscape maintenance practices of Southern Californians. Hort Technol. 2022, 32, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.M.; Larson, K.L.; Andrade, R. Attitudinal and structural drivers of preferred versus actual residential landscapes in a desert city. Urban Ecosyst. 2020, 23, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, K.; Lerch, D.; Müller, A.K.; Simons, N.K.; Blüthgen, N.; Harnisch, M. Flower power in the city: Replacing roadside shrubs by wildflower meadows increases insect numbers and reduces maintenance costs. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runfola, D.M.; Polsky, C.; Nicolson, C.; Giner, N.M.; Pontius, R.M., Jr.; Krahe, J.; Decatur, A. A growing concern? Examining the influence of lawn size on residential water use in suburban Boston, MA, USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 119, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Carignan-Guillemette, L.; Turcotte, C.; Maire, V.; Proulx, R. Ecological and economic benefits of low-intensity urban lawn management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 57, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Dushkova, D.; Martin, D.; Mofrad, F.; Stewart, K.; Hughes, M. From One to Many Natures: Integrating Divergent Urban Nature Visions to Support Nature-Based Solutions in Australia and Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Tran, D.K.; Tenorio, R. Challenges and Stakeholder Perspectives on Implementing Ecological Designs in Green Public Spaces: A Case Study of Hue City, Vietnam. Land 2023, 12, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC—European Commission. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities; CEC: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- IUCN. Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions. A User-Friendly Framework for the Verification, Design and Scaling Up of NbS, 1st ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Cabecinha, E.; Andrade, A. (Eds.) Applying the IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions™: 21 Case Studies from Around the Globe; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dushkova, D.; Haase, D. Resilient cities, healthy communities, and sustainable future: How do nature-based solutions contribute? In Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hansen, R. Principles for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Ambio 2022, 51, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S. Growing Biodiverse Urban Futures: Renaturalization and Rewilding as Strategies to Strengthen Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Sardeshpande, M.; Rupprecht, C.D.D. Urban Rewilding for Sustainability and Food Security. Land Use Policy 2025, 149, 107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Schmidt, K.R. Stadt Augsburg—Blumenwiesen, Entwicklung von artenreichen und biologisch aktiven Grünflächen. Pflegeprogramm Siebentischpark. Das Gartenamt 1982, 31, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, N.; Wolf, G. Blumenwiesen in Siedlungsräumen. Gart. Landsch. 1985, 95, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, N. Südbayerische Parkrasen—Soziologie und Dynamik bei unterschiedlicher Pflege (South Bavarian park lawns—Sociology and dynamics under different management). Diss. Bot. 1988, 123, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, N. Lawns in German Cities. A Phytosociological comparison. In Urban Ecology; Sukopp, H., Hejny, S., Eds.; Kowarik, I., Co-Ed.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, S.; Hannig, K.; Möller, M.; Schirmel, J. Reducing management intensity and isolation as promising tools to enhance ground-dwelling arthropod diversity in urban grasslands. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, S.; Gathof, A.K.; Grossmann, A.J.; Kowarik, I.; Fischer, L.K. Wild bees in urban grasslands: Urbanisation, functional diversity and species traits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 196, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, D.; Macegoniuk, S.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Sikorski, P. Energy crops in urban parks as a promising alternative to traditional lawns—Perceptions and a cost-benefit analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, D.; Ciężkowski, W.; Babańczyk, P.; Chormański, J.; Sikorski, P. Intended wilderness as a nature-based solution: Status, identification and management of urban spontaneous vegetation in cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filibeck, G.; Petrella, P.; Cornelini, P. All ecosystems look messy, but some more so than others: A case-study on the management and acceptance of Mediterranean urban grasslands. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 15, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonati, M.; Probo, M.; Gorlier, A.; Pittarello, M.; Scariot, V.; Lombardi, G.; Ravetto Enri, S. Plant diversity and grassland naturalness of differently managed urban areas of Torino (NW Italy). Acta Hortic. 2018, 1215, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.H.; Yue, Z.E.J.; Tan, Y.C. Observation of floristic succession and biodiversity on rewilded lawns in a tropical city. Lands. Res. 2017, 42, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Hughes, M.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Mofrad, F. The Lawn as a Social and Cultural Phenomenon in Perth Western Australia. Land 2024, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Hughes, M.; Mofrad, F.; Cabanek, A. Challenging the Norm of Lawns in Public Urban Green Space: Insights from Expert Designers, Turf Growers and Managers. Land 2025, 14, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretzel, F.; Gaetani, M.; Vannucchi, F.; Barbati, A.; Rossi, F.; Santoro, A. A multifunctional alternative lawn where warm-season grass and cold-season flowers coexist. Landscape Ecol. Eng. 2020, 16, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretzel, F.; Vannucchi, F.; Pezzarossa, B.; Paraskevopoulou, A.; Romano, D.; Barbati, A.; Rossi, F. Establishing wildflower meadows in anthropogenic landscapes. Front. Hortic. 2023, 2, 1248785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, M.; David, F.J.; Cunningham, S.W.; Liu, Y.; Singh, R.; Martinez, A.; Brown, K. Rewilding in Miniature: Suburban Meadows Can Improve Soil Microbial Biodiversity and Soil Health. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 85, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramer, H.; Nelson, K.C.; Spivak, M.; Watkins, E.; Wolfin, J.; Pulscher, M. Exploring park visitor perceptions of ‘flowering bee lawns’ in neighborhood parks in Minneapolis, MN, US. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfin, J.; Watkins, E.; Lane, I.; Portman, Z.; Spivak, M. Floral enhancement of turfgrass lawns benefits wild bees and honey bees (Apis mellifera). Res. Sq. 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M. Lawn Alternatives in Sweden: From Theory to Practice; Manual; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson, L.M. Methods of establishing species-rich meadow biotopes in urban areas. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 103, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Lee, J.; Nicholls, E.; Goulson, D. Sown mini-meadows increase pollinator diversity in gardens. J. Insect Conserv. 2022, 26, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.S.; Fellowes, M.D. The grass-free lawn: Management and species choice for optimum ground cover and plant diversity. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Ignatieva, M.; Nilon, C.H.; Werner, P.; Zipperer, W.C. Patterns and trends in urban biodiversity and landscape design. In Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities: A Global Assessment; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 123–174. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, S.; Brabant, C.; Tessier, S.; Jung, V. From urban lawns to urban meadows: Reduction of mowing frequency increases plant taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, H. Organic Lawn Care: Growing Grass the Natural Way; University of Texas Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarchik, G.; D’Amore, C. Growing an Edible Landscape: How to Transform Your Outdoor Space into a Food Garden; Cool Springs Press: Franklin, TN, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, C. Your Edible Yard: Landscaping with Fruits and Vegetables, Illustrated ed.; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, M.; Bertelsen, M.; Windhager, S.; Zafian, H. The performance of native and non-native turfgrass monocultures and native turfgrass polycultures: An ecological approach to sustainable lawns. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, D.S.; Humphrey, C.E.; Kyndt, J.A.; Moore, T.C. Native plant gardens support more microbial diversity and higher relative abundance of potentially beneficial taxa compared to adjacent turf grass lawns. Urban Ecosyst. 2023, 26, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Konstantinova, A.; Yang, F. Cultural ecosystem services of urban green spaces: How and what people value in urban nature? In Advanced Technologies for Sustainable Development of Urban Green Infrastructure; Vasenev, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 292–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Taherkhani, M.; Konstantinova, A.; Vasenev, V.I.; Dovletyarova, E. Understanding factors affecting the use of urban parks through the lens of ecosystem services and blue-green infrastructure: The case of Gorky Park, Moscow, Russia. Land 2025, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Hedblom, M. An alternative urban green carpet. Science 2018, 362, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ignatieva, M.; Wissman, J.; Ahrné, K.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, S. Relationships between Multi-Scale Factors, Plant and Pollinator Diversity, and Composition of Park Lawns and other Herbaceous Vegetation in a Fast-Growing Megacity of China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 185, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Florgård, C.; Lundin, K. Lawns in Sweden: History and etymological roots, European parallels and future alternative pathways. Bebyggelsehistorisk Tidskr. 2018, 75, 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Müller, N.; Nilon, C. Editorial for special issue on “Integrating Biodiversity in the Urban Planning and Design Processes”. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noss, R.F. Wilderness recovery and ecological restoration: An example for Florida. Earth First 1985, 5, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, D.; Wolke, H.; Koehler, B.; Netherton, S. The Earth First! Wilderness Preserve System. Wild Earth 1991, 1, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Soulé, M.E.; Noss, R. Rewilding and biodiversity: Complementary goals for continental conservation. Wild Earth 1998, 8, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sukopp, H.; Blume, H.; Kunick, W. The soil, flora and vegetation of Berlin’s waste lands. In Nature in Cities: The Natural Environment in the Design and Development of Urban Green Space; Laurie, I., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1979; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I. Zum menschlichen Einfluss auf Flora und Vegetation. Theoretische Konzepte und ein Quantifizierungsansatz am Beispiel von Berlin (West). Landschaftsentwicklung Umweltforsch. 1988, 56, 1–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I. Urban wilderness: Supply, demand and access. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, P.B.; Carthey, A.J.R.; Banks, P.B.; Brewster, R.; Grueber, C.E.; Houston, D.; Martin, J.M.; McManus, P.; Roncolato, F.; van Eeden, L.M.; et al. Urban rewilding to combat global biodiversity decline. BioScience 2025, 75, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lima, M.F. The association between maintenance and biodiversity in urban green spaces: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 251, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Schulte to Bühne, H.; Cunningham, A.A.; Dancer, A.; Debney, A.; Durant, S.M.; Hoffmann, M.; Laughlin, B.; Pilkington, J.; Pecorelli, J.; et al. Rewilding Our Cities; ZSL Report: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ZSL. Rewilding Our Cities. Available online: https://issuu.com/zoologicalsocietyoflondon/docs/zsl_rewilding_our_cities_report (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Kowarik, I. Working with wilderness: A promising direction for urban green spaces. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2021, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon, S.; Webb, J.; Semertzi, A.; Samangooei, M. Wild ways: A scoping review to understand urban-rewilding behavior in relation to adaptations to private gardens. Cities Health 2023, 7, 888–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H. What is Rewilding? (Extended Version). 2019. Available online: https://rewildingnews.com/2019/01/24/what-is-rewilding-extended-version/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, G.; Ekroos, J.; Persson, A.S.; Pettersson, L.B.; Öckinger, E. Intensive management reduces butterfly diversity over time in urban greenspaces. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.H.; Lekies, K.S. Childhood Collecting in Nature: Quality Experience in Important Places. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, R.; Valkó, O.; Fischer, L.K.; Deák, B.; Klaus, V.H. Ecological Restoration and Biodiversity-Friendly Management of Urban Grasslands—A Global Review on the Current State of Knowledge. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhomme-Duchadeuil, A. Urban Naturalistic Meadows to Promote Cultural and Regulating Ecosystem Services. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, M.; Velbert, F.; Schwenzfeier, S.; Kleinebecker, T.; Klaus, V.H. Patterns and potentials of plant species richness in high- and low-maintenance urban grasslands. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2017, 20, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrt, M.; Bossdorf, O.; Freitag, M.; Bucharova, A. Less is more! Rapid increase in plant species richness after reduced mowing in urban grasslands. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2020, 42, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.S.; Fellowes, M.D.E. Towards a Lawn without Grass: The Journey of the Imperfect Lawn and Its Analogues. Stud. Hist. Gardens Des. Landsc. 2013, 33, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southon, G.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Dunnett, N.; Hoyle, H.; Evans, K.L. Biodiverse perennial meadows have aesthetic value and increase residents’ perceptions of site quality in urban green-space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trémeau, J.; Olascoaga, B.; Backman, L.; Karvinen, E.; Vekuri, H.; Kulmala, L. Lawns and meadows in urban green space—A comparison from greenhouse gas, drought resilience and biodiversity perspectives. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastian, L.; Unterweger, P.A.; Betz, O. Influence of the reduction of urban lawn mowing on wild bee diversity (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2016, 49, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani-Beni, M.; Zhang, B.; Xie, G.; Xu, J. Impact of urban park’s tree, grass, and waterbody on microclimate in hot summer days: A case study of Olympic Park in Beijing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.R.; Nelson, K.C.; Dahmus, M.E. What’s in a yardscape? A case study of emergent ecosystem services and disservices within resident yardscape discourses in Minnesota. Urban Ecosyst. 2020, 23, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bø, S.M.; Bohne, R.A.; Lohne, J. Environmental impacts of artificial turf: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 10205–10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, M.; Sancar, B. Urban Lawn Management for Improving Ecosystem Services of Turfgrasses. In Architectural Sciences and Ecology; Çakır, M., Tuğluer, M., Firat Örs, P., Eds.; IKSAD Publishing House, Institution of Economic Development and Social Researches: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022; pp. 253–295. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sachs, N.A. Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cumberbatch, I.S.; Richardson, L.; Grant-Bier, E.; Kayali, M.; Mbithi, M.; Riviere, R.F.; Xia, E.; Spinks, H.; Mills, G.; Tuininga, A.R. Artificial Turf Versus Natural Grass: A Case Study of Environmental Effects, Health Risks, Safety, and Cost. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.K.; Neuenkamp, L.; Lampinen, J.; Tuomi, M.; Alday, J.G.; Bucharova, A.; Cancellieri, L.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Čeplová, N.; Cerveró, L.; et al. Public attitudes toward biodiversity-friendly greenspace management in Europe. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.A. Artificial Lawns: Environmental and Societal Considerations of an Ecological Simulacrum. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Crane II, G.; Hornberger, A.; Carrico, A. The effects of household management practices on the global warming potential of urban lawns. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 151, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybysz, A.A.; Popek, R.; Stankiewicz-Kosyl, M.; Zhu, C.Y.; Małecka-Przybysz, M.; Maulidyawati, T.; Mikowska, K.; Koc, A.; Urbanek, H.; Kowalski, A. Where trees cannot grow–particulate matter accumulation by urban meadows. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchepeleva, A.S.; Vizirskaya, M.M.; Vasenev, V.I.; Vasenev, I.I. Analysis of Carbon Stocks and Fluxes of Urban Lawn Ecosystems in Moscow Megapolis. In Urbanization: Challenge and Opportunity for Soil Functions and Ecosystem Services; Vasenev, V., Dovletyarova, E., Cheng, Z., Prokof’eva, T., Morel, J., Ananyeva, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thienelt, T.S.; Anderson, D.E. Estimates of energy partitioning, evapotranspiration, and net ecosystem exchange of CO2 for an urban lawn and a tallgrass prairie in the Denver metropolitan area under contrasting conditions. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 1201–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.L.; Kao-Kniffin, J. Applying biodiversity and ecosystem function theory to turfgrass management. Crop Sci. 2017, 57 (Suppl. S1), S238–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgeon, A.J.; Fidanza, M.A. Perspective on the History of Turf Cultivation. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2017, 13, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Delden, L.; Larsen, E.; Rowlings, D.; Scheer, C.; Grace, P. Establishing turf grass increases soil greenhouse gas emissions in peri-urban environments. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 19, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.M.; Neil, C.; Groffman, P.M. Continental-scale homogenization of residential lawn plant communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Sun, G.; Fan, P. The American Lawn Revisited: Awareness, Education and Culture as Public Policies Toward Sustainable Lawn. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2015, 10, 107–115. Available online: https://ph.pollub.pl/index.php/preko/article/view/4933 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Hu, S.; Liu, J.; Que, J.; Su, X.; Li, B.; Quan, C. Perceptions of Urban Rewilding in a Park with Secondary Succession Vegetation Growth on Lake Silt: Landscape Preferences and Perceived Species Richness. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 104, 128648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, A.; Melnichuk, I.; Dvadtsatova, T.; Loginova, A.; Babich, G.; Ignatieva, M. What Do Residents of St. Petersburg Value in Urban Lawns? Alternative Lawns and Their Consideration in Lawns’ Management. In Green Infrastructure and Climate Resilience; Korneykova, M., Vasenev, V., Dovletyarova, E., Valentini, R., Gunina, A., Poddubsky, A., Cheng, Z., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poškus, M.; Poškiene, D. The grass is greener: How greenery impacts the perceptions of urban residential property. Soc. Inq. Into Well-Being 2015, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, J.; Brady, E. Environmental aesthetics and rewilding. Environ. Values 2017, 26, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, S.M.; Crittenden, J.C. Sustainable Plants in Urban Parks: A Life Cycle Analysis of Traditional and Alternative Lawns in Georgia, USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 122, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-P.; Ignatieva, M.; Larsson, A.; Xiu, N.; Zhang, S.-X. Historical Development and Practices of Lawns in China. Environ. Hist. 2019, 25, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, C. Show me your garden and I will tell you how sustainable you are: Dutch citizens’ perspectives on conserving biodiversity and promoting a sustainable urban living environment through domestic gardening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthoux, S.; Chollet, S. Wilding cities for biodiversity and people: A transdisciplinary framework. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1234–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yuan, T. The effects of precipitation change on urban meadows in different design models and substrates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, N.; von Atzigen, A. Understanding the factors shaping the attitudes towards wilderness and rewilding. In Rewilding; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabon, V.; Bùi, M.; Kühne, H.; Seitz, B.; Kowarik, I.; von der Lippe, M.; Buchholz, S. Endangered animals and plants are positively or neutrally related to wild boar (Sus scrofa) soil disturbance in urban grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, S.; Convery, I.; Hawkins, S.; Beyers, R.; Eagle, A.; Kun, Z.; Van Maanen, E.; Cao, Y.; Fisher, M.; Edwards, S.R.; et al. Guiding principles for rewilding. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. The psychology of rewilding. In Rewilding; Pettorelli, N., Durant, S., Du Toit, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, D. Rethinking rewilding. Geoforum 2015, 65, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, S.J.; White, P.C.L. Achieving positive social outcomes through participatory urban wildlife conservation projects. Wildlife Res. 2016, 42, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, L.; Echberg, D.; Napper, C.; Hahs, A.K.; Palma, E. The lawn is buzzing: Increasing insect biodiversity in urban greenspaces through low-intensity mowing. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv: 2025.09.23.677970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumaw, L.; Bekessy, S. Wildlife gardening for collaborative public-private biodiversity conservation. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Wolch, J. Rewilding cities. In Rewilding; Pettorelli, N., Durant, S., Du Toit, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Bullock, J.M. Restore or rewild? Implementing complementary approaches to bend the curve on biodiversity loss. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2023, 4, e12244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotherham, I. New Series—‘Rewilding Your Garden’—Rewilding Your Lawn! Ian’s Walk on the Wild Side 2019. Available online: https://ianswalkonthewildside.wordpress.com/2019/05/14/new-series-rewilding-your-garden-rewilding-your-lawn/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Turnbull, J.; Fry, T.; Lorimer, J. (Re)wilding London: Fabric, politics, and aesthetics. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2025, 50, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartmann, F.M.; Lorimer, J. Messy natures: The political aesthetics of nature recovery. People Nat. 2024, 6, 1123–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.; Moxon, S. A study protocol to understand urban rewilding behavior in relation to adaptations to private gardens. Cities Health 2021, 7, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoderer, B.M. Reconnecting People and Wild Nature in Cities: Experienced Barriers to Using Urban Wild Spaces among Non-Users. People Nat. 2025, 7, 3088–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoderer, B.M.; Wieser, H. Giving space back to nature in cities? A multi-scenario analysis of the acceptability of urban rewilding among local communities. People Nat. 2025, 7, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Haase, D. Not Simply Green: Nature-Based Solutions as a Concept and Practical Approach for Sustainability Studies and Planning Agendas in Cities. Land 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Melnichuk, I. Urban greening as a response to societal challenges: Toward biophilic megacities (case studies of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, Russia). In Making Green Cities: Concepts, Challenges and Practice; Breuste, J., Artmann, M., Ioja, C., Qureshi, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, G. Lawn: Object Lessons; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, P. A New Garden Ethic; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Erbino, C.; Toccolini, A.; Vagge, I.; Ferrario, P.S. Guidelines for the design of a healing garden for the rehabilitation of psychiatric patients. J. Agric. Eng. 2015, 46, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerling, M.; Müller, N. The relationship between landscape design style and the conservation value of parks: A case study of a historical park in Weimar, Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnett, N.; Hitchmough, J. (Eds.) The Dynamic Landscape. Design, Ecology, and Management of Naturalistic Urban Planting, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Wolff, M. Connecting Urban Nature: Allotment Gardens’ Transition Potential to the Connectivity of Natura 2000 Areas. SSRN 2025. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5526731 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Iamonico, D. Biodiversity in Urban Areas: The Extraordinary Case of Appia Antica Regional Park (Rome, Italy). Plants 2022, 11, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancette, C. We Rewilded Our Yard DIY Style—And Got the Neighbours on Board Too. Rewilding Mag. 17 February 2024. Available online: https://www.rewildingmag.com/rewilded-yard-neighbours-on-board/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Kowarik, I.; Langer, A. Natur-Park Südgelände: Linking Conservation and Recreation in an Abandoned Railyard in Berlin. In Wild Urban Woodlands; Kowarik, I., Körner, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Erixon, H.; Ernstson, H.; Grahn, S.; Kärsten, C.; Marcus, L.; Torsvall, J. Principles of Social-Ecological Urbanism: Case Study: Albano Campus, Stockholm; Edition: 2013:3; School of Architecture and the Built Environment, Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Langemeyer, J.; Wedgwood, D.; McPhearson, T.; Baró, F.; Madsen, A.L.; Barton, D.N. Creating urban green infrastructure where it is needed—A spatial ecosystem service-based decision analysis of green roofs in Barcelona. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Bending, G.D.; Clark, R.; Corstanje, R.; Dunnett, N.; Evans, K.L.; Hall, D.M.; Hilton, S.; Smith, G.M.; Macgregor, C.J.; et al. Urban meadows as an alternative to short mown grassland: Effects of composition and height on biodiversity. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbe, S.; Maurer, U.; Schmitz, S.; Sukopp, H. Biodiversity in Berlin and Its Potential for Nature Conservation. Landscape Urban Plan. 2003, 62, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilderness Foundation Global. Global Charter for Rewilding the Earth. Advancing Nature-Based Solutions to the Extinction and Climate Crises. 2020. Available online: https://issuu.com/ijwilderness/docs/rewildingcharter_final2 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

| Category of Research | Research Aspect (s) | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Lawn and the benefits provided | 1.1. Biodiversity and vegetation aspects | Aguilera et al., 2019 [79]; Baldi et al., 2023 [58]; Beery and Lekies, 2019 [80]; Buchholz et al., 2018, 2020 [34,35]; Chollet et al., 2018 [53]; Fekete et al., 2024 [81]; Griffiths-Lee et al., 2022 [50]; Hedblom et al., 2017 [1]; Hwang et al., 2017 [40]; Ignatieva, 2017 [48]; Lhomme-Duchadeuil, 2018 [82]; Lonati et al., 2018 [39]; Müller et al., 2013 [52]; Rudolph et al., 2017 [83]; Sehrt et al., 2020 [84]; Smith and Fellowes, 2013, 2014 [51,85]; Southon et al., 2017 [86]; Trémeau et al., 2023 [87]; Wastian et al., 2016 [88]; Winkler et al., 2024 [13]; Wolfin et al., 2021 [47]; Yang et al., 2019a [4] |

| 1.2. Ecosystem services and disservices provided by lawns | Amani-Beni et al., 2018 [89]; Barnes et al., 2020 [90]; Bø et al., 2024 [91]; Chollet et al., 2018 [53]; Çakır and Sancar, 2022 [92]; Marcus and Sachs, 2014 [93]; Cumberbatch et al., 2025 [94]; Fekete et al., 2024 [81]; Filibeck et al., 2016 [38]; Fischer et al., 2020 [95]; Francis, 2018 [96]; Griffiths-Lee et al., 2022 [50]; Gu et al., 2015 [97]; Hedblom et al., 2017 [1]; Ignatieva and Hedblom, 2018 [61]; Ignatieva et al., 2020 [8]; Monteiro, 2017 [11]; Müller et al., 2013 [52]; Przybysz et al., 2021 [98]; Rudolph et al., 2017 [83]; Shchepeleva et al., 2019 [99]; Thienelt and Anderson, 2021 [100]; Thompson and Kao-Kniffin, 2017 [101]; Trémeau et al., 2023 [87]; Turgeon and Fidanza, 2017 [102]; van Delden et al., 2016 [103]; Wang et al., 2016 [12]; Wheeler et al., 2017, 2020 [16,104]; Winkler et al., 2024 [13]; Zhang et al., 2015 [105] | |

| 2. Lawn as a socio-cultural phenomenon | 2.1. Public perception, attitude, and preferences | Barnes, 2022 [90]; Beery & Lekies, 2019 [80]; Filibeck et al., 2016 [38]; Fischer et al., 2020 [95]; Francis, 2018 [96]; Hartin et al., 2022 [15]; Hedblom et al., 2017 [1]; Hu et al., 2025 [106]; Konstantinova et al., 2025 [107]; Ignatieva, 2017 [48]; Ignatieva et al., 2020 [8]; Ignatieva et al., 2024, 2025 [41,42]; Poškus and Poškienė, 2015 [108]; Prior and Brady, 2017 [109]; Ramer et al., 2019 [46]; Southon et al., 2017 [86]; Yang et al., 2019 [4]; Yang et al., 2019 [62]; Wheeler et al., 2020 [104]; Zhang et al., 2015 [105] |

| 2.2. History of lawn development, management, and maintenance | Bretzel et al., 2020 [43]; Fekete et al., 2024 [81]; Hartin et al., 2022 [15]; Ignatieva, 2017 [48]; Ignatieva et al., 2018 [63]; Ignatieva et al., 2020 [2]; Ignatieva and Hedblom, 2018 [61]; Konstantinova et al., 2025 [107]; Paudel and States, 2023 [6]; Sehrt et al., 2020 [84]; Smetana and Crittenden, 2014 [110]; Smith and Fellowes, 2013, 2014 [51,85]; Trémeau et al., 2023 [87]; Turgeon and Fidanza, 2017 [102]; Yang et al., 2019 [111]; Wheeler et al., 2020 [104]; Zhang et al., 2015 [105] | |

| 3. Sustainable alternatives/Lawn-related NBS | 3.1. Nature-based alternatives to conventional lawns, lawn-related NBS, and sustainable lawn management | Baldi et al., 2023 [58]; Barnes et al., 2020 [90]; Beumer, 2018 [112]; Bonthoux and Chollet, 2024 [113]; Bretzel et al., 2020, 2023 [43,44]; Buchholz et al., 2018 [34]; Chollet et al., 2018 [53]; Çakır and Sancar, 2022 [92]; Dushkova et al., 2021, 2025a [59,60]; Fekete et al., 2024 [81]; Fischer et al., 2020 [95]; Garret, 2014 [54]; Gu et al., 2015 [97]; Hwang et al., 2017 [40]; Jiang and Tuan, 2023 [114]; Smith and Fellowes, 2014 [51]; Konstantinova et al., 2025 [107]; Ignatieva, 2017 [48]; Ignatieva and Hedblom, 2018 [61]; Ignatieva et al., 2023 [20]; Lonati et al., 2018 [39]; Mårtensson, 2017 [49]; Müller et al., 2013 [52]; Pilarchik and D’Amore, 2023 [55]; Przybysz et al., 2021 [98]; Rudolph et al., 2017 [83]; Sehrt et al., 2020 [84]; Smith and Fellowes, 2013, 2014 [51,85]; Stevens, 2020 [56]; Wolfin et al., 2021 [47] |

| 3.2. Lawn and rewilding | Bauer and von Atzigen, 2019 [115]; Bonthoux and Chollet, 2024 [113]; Cabon et al., 2022 [116], Carver et al., 2021 [117]; Chollet et al., 2018 [53]; Clayton, 2019 [118]; Fischer et al., 2020 [95]; Jørgensen, 2015 [119]; Hobbs and White, 2016 [120]; Hwang et al., 2017 [40]; Hu et al., 2025 [106]; Mata et al., 2025 [121]; Moxon et al., 2023 [76]; Mumaw and Bekessy, 2017 [122]; Owens and Wolch, 2019 [123]; Pettorelli and Bullock, 2023 [124]; Prior and Brady, 2017 [109]; Rotherham, 2019 [125]; Southon et al., 2017 [86]; Sikorska et al., 2021, 2023 [36,37]; Stone, 2019 [77]; Tessler et al., 2023 [45]; Trémeau et al., 2023 [87]; Turnbull et al., 2025 [126]; Wartmann and Lorimer, 2024 [127]; Webb and Moxon, 2021 [128]; Winkler et al., 2024 [13]; Zoderer, 2025 [129]; Zoderer and Wieser, 2025 [130] |

| Case Study | Ecological Parameters, Incl. Biodiversity Aspects | Social Aspects (Perception, Attitude, and Preferences) | Management and Maintenance Specifics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uppsala, Stockholm (Sweden) | Direct (landscape) observation, data on plants and pollinators | on-site questionnaire survey among citizens, and observational studies of people’s activities | Semi-structured interviews with experts * |

| Berlin, Leipzig (Germany) | Direct (landscape) observation, plant biodiversity assessment of lawns in parks, and verges | Walking interviews with park visitors, observational studies of people’s activities | Semi-structured interviews with experts * |

| Barcelona (Spain) and Rome (Italy) | Direct (landscape) observation | Observational studies of people’s activities | Analysis of documents and policies regulating lawn construction and management |

| Moscow, St.-Petersburg (Russia) | Direct (landscape) observation, plant biodiversity assessment of lawns in parks and private gardens | Online and on-site questionnaire survey among citizens | Analysis of documents regulating lawn construction and management |

| Beijing, Xi’an (China) | Landscape observation, plant and pollinator biodiversity assessment of lawns in parks, green corridors, and verges | Observational studies of people’s activities, walking interviews | Semi-structured interviews with experts * |

| Hue City (Vietnam) | Landscape observation in public parks and private gardens (lawn as a part of green spaces). | Semi-structured interviews with experts * | Semi-structured interviews with experts * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M. Rethinking Urban Lawns: Rewilding and Other Nature-Based Alternatives. Diversity 2025, 17, 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120830

Dushkova D, Ignatieva M. Rethinking Urban Lawns: Rewilding and Other Nature-Based Alternatives. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):830. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120830

Chicago/Turabian StyleDushkova, Diana, and Maria Ignatieva. 2025. "Rethinking Urban Lawns: Rewilding and Other Nature-Based Alternatives" Diversity 17, no. 12: 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120830

APA StyleDushkova, D., & Ignatieva, M. (2025). Rethinking Urban Lawns: Rewilding and Other Nature-Based Alternatives. Diversity, 17(12), 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120830