Afrotropical Stingless Bees Illustrate a Persistent Cultural Blind Spot in Research, Policy and Conservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Approach and Conceptual Framework

3. The Cultural Ecosystem Services of Afrotropical Stingless Bees (Apidae, Meliponini)

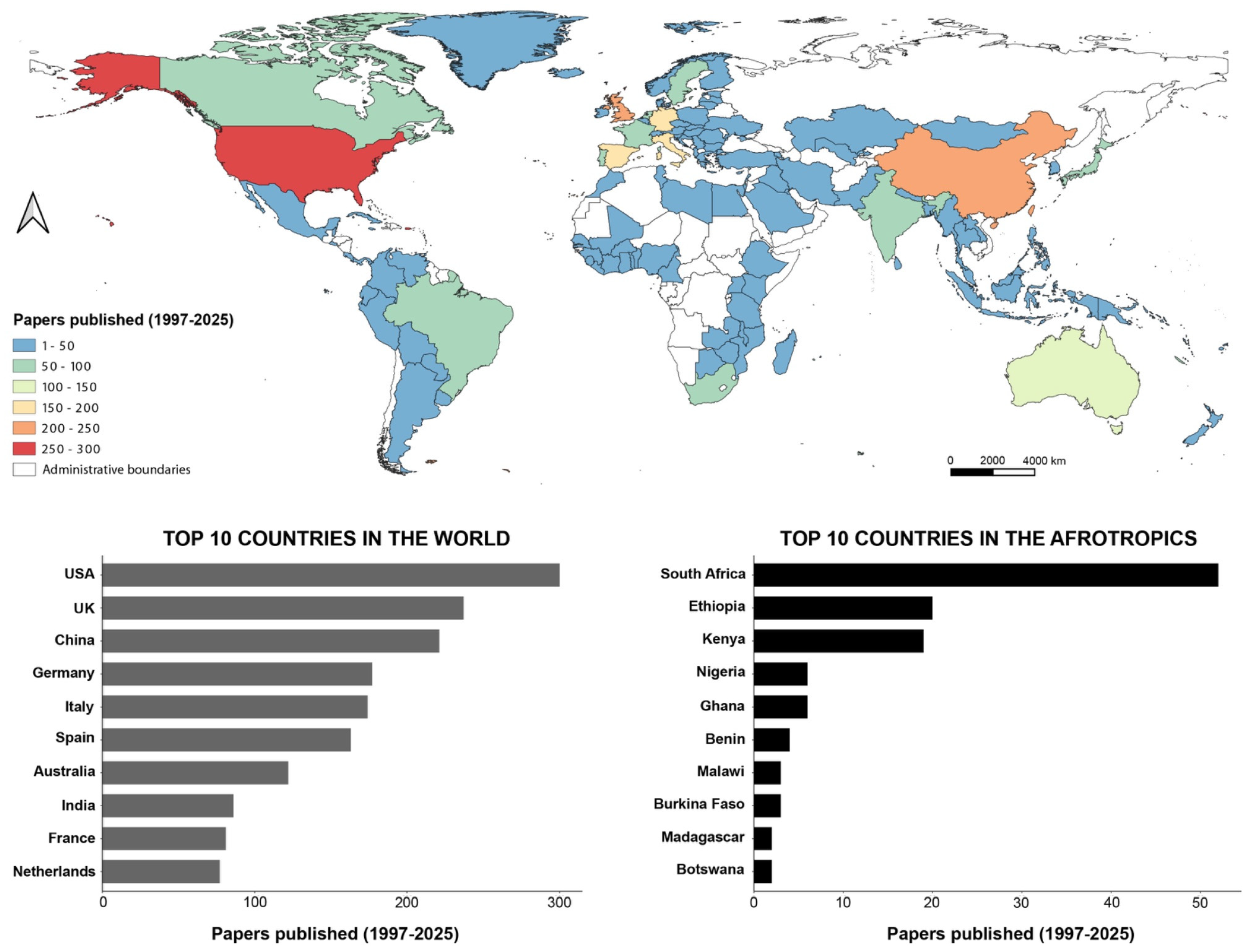

3.1. Quantifying the Afrotropical Cultural Blind Spot: A Brief Bibliometric Illustration

3.2. Defining the Spectrum of CESs Associated with Afrotropical Stingless Bees

4. Toward a Better Integration of CESs in Afrotropical Stingless Bee Research and Conservation

4.1. Difficulty in Categorization and Quantification

4.2. Disciplinary Silos and Methodological Constraints

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biesmeijer, J.; Roberts, S.; Reemer, M.; Ohlemüller, R.; Edwards, M.; Peeters, T.; Schaffers, A.P.; Potts, S.; Kleukers, R.; Thomas, C.; et al. Parallel Declines in Pollinators and Insect-Pollinated Plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science 2006, 313, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBuhn, G.; Vargas Luna, J. Pollinator Decline: What Do We Know about the Drivers of Solitary Bee Declines? Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 46, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo Raiol, R.; Gastauer, M.; Campbell, A.; Borges, R.; Awade, M.; Giannini, T. Specialist Bee Species Are Larger and Less Phylogenetically Distinct Than Generalists in Tropical Plant–Bee Interaction Networks. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 699649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Roberts, S.P.M.; Kemp, J.; Rasmont, P.; Kuhlmann, M.; García Criado, M.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Bogusch, P.; Dathe, H.H.; De la Rúa, P.; et al. European Red List of Bees; IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jakab-Dóra, A.J.; Tóth, M.; Szarukán, I.; Szanyi, S.; Józan, Z.; Sárospataki, M.; Nagy, A. Long-Term Changes in the Composition and Distribution of the Hungarian Bumble Bee Fauna (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Bombus). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2023, 96, 207–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, M.; Goslee, S.; Douglas, M.; Tooker, J.; Grozinger, C. Wild Bees as Winners and Losers: Relative Impacts of Landscape Composition, Quality, and Climate. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1250–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertommen, W.; Vanormelingen, P.; D’Haeseleer, J.; Wood, T.; Baugnée, J.-Y.; De Blanck, T.; De Rycke, S.; Deschepper, C.; Devalez, J.; Feys, S.; et al. New and Confirmed Wild Bee Species (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Apiformes) for the Fauna of Belgium, with Notes on the Rediscovery of Regionally Extinct Species. Belg. J. Entomol. 2024, 149, 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, J.; Fragoso, F.P. What Are the Main Reasons for the Worldwide Decline in Pollinator Populations? CABI Rev. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, O.C.; Maggioni, M.; Dani, F.R. Environmental Ameliorations and Politics in Support of Pollinators. Experiences from Europe: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 362, 121219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.L.; Grames, E.M.; Forister, M.L.; Berenbaum, M.R.; Stopak, D. Insect Decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a Thousand Cuts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023989118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; De Santis, L.; Sentil, A.; Michez, D. Drivers of Wild Bee Abundance and Diversity in Social-Ecological Landscapes. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 62, e03765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Polidori, C. How City Traits Affect Taxonomic and Functional Diversity of Urban Wild Bee Communities: Insights from a Worldwide Analysis. Apidologie 2022, 53, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, N.J. A Phylogenetic Approach to Conservation Prioritization for Europe’s Bumblebees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus). Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.; Gibbs, J.; Winfree, R. Phylogenetic Homogenization of Bee Communities across Ecoregions. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Samadder, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Lai, Y.-C. Understanding Pesticide-Induced Tipping in Plant-Pollinator Networks across Geographical Scales: Prioritizing Richness and Modularity over Nestedness. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 014407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martén-Rodríguez, S.; Cristobal-Pérez, E.J.; de Santiago-Hernández, M.H.; Huerta-Ramos, G.; Clemente-Martínez, L.; Krupnick, G.; Taylor, O.; Lopezaraiza-Mikel, M.; Balvino-Olvera, F.J.; Sentíes-Aguilar, E.M.; et al. Untangling the Complexity of Climate Change Effects on Plant Reproductive Traits and Pollinators: A Systematic Global Synthesis. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.B.B.S.; Oliveira, H.F.M.; Dáttilo, W.; Paolucci, L.N. Anthropogenic Impacts on Plant-Pollinator Networks of Tropical Forests: Implications for Pollinators Coextinction. Biodivers. Conserv. 2025, 34, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, K.; Ferreira, A.B.; Timberlake, T.P.; dos Santos, C.F. The Impact of Pollinator Decline on Global Protein Production: Implications for Livestock and Plant-Based Products. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 50, e02815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijn, D.; Winfree, R.; Bartomeus, I.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Henry, M.; Isaacs, R.; Klein, A.-M.; Kremen, C.; M’Gonigle, L.K.; Rader, R.; et al. Delivery of Crop Pollination Services Is an Insufficient Argument for Wild Pollinator Conservation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, S.G.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Kremen, C.; Neumann, P.; Schweiger, O.; Kunin, W.E. Global Pollinator Declines: Trends, Impacts and Drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, D.M.S.; Leventon, J.; Rau, A.-L.; Borgemeister, C.; von Wehrden, H. A Review of Ecosystem Service Benefits from Wild Bees across Social Contexts. Ambio 2017, 46, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-González, A.; Camou-Guerrero, A.; del-Val, E.; Ramírez, M.I.; Porter-Bolland, L. Biocultural Diversity Loss: The Decline of Native Stingless Bees (Apidae: Meliponini) and Local Ecological Knowledge in Michoacán, Western México. Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Methodological Assessment of the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES); IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.W.; Gould, R.; López de la Rama, R.; Eyster, H.N. What If Cultural Ecosystem Services Were Relational? A Research Agenda for Nature’s Contributions to Well-being—And Human Action. In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Ecosystem Services; McElwee, P.D., Allen, K.E., Gould, R.K., Hsu, M., He, J., Eds.; Taylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2025; pp. 442–454. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, R.K.; Satterfield, T.; Leong, K.; Fisk, J. The Generations of Cultural Ecosystem Services Research. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 39, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braat, L.C.; de Groot, R. The Ecosystem Services Agenda: Bridging the Worlds of Natural Science and Economics, Conservation and Development, and Public And Private Policy. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; de Groot, R.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The History of Ecosystem Services in Economic Theory and Practice: From Early Notions to Markets and Payment Schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffus, N.E.; Christie, C.R.; Morimoto, J. Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them. Insects 2021, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, S.; Burgess, N.; Fa, J.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Molnár, Z.; Robinson, C.; Watson, J.; Zander, K.; Austin, B.; Brondízio, E.; et al. A Spatial Overview of the Global Importance of Indigenous Lands for Conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, L. Linguistic, Cultural, And Biological Diversity. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2005, 34, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, C. Stingless Bees: Their Behaviour, Ecology and Evolution; Fascinating Life Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-60089-1. [Google Scholar]

- Noiset, P.; Héger, M.; Salmon, C.; Kwapong, P.; Combey, R.; Thevan, K.; Warrit, N.; Rojas-Oropeza, M.; Cabirol, N.; Zaragoza-Trello, C.; et al. Ecological and Evolutionary Drivers of Stingless Bee Honey Variation at the Global Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Héger, M.; Noiset, P.; Nkoba, K.; Vereecken, N.J. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Non-Food Uses of Stingless Bee Honey in Kenya’s Last Pocket of Tropical Rainforest. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, A.A.; Tegegne, F.M.; Tack, A.J.M. Indigenous Knowledge of Ground-Nesting Stingless Bees in Southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2021, 41, 2617–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiprono, S.J.; Mengich, G.; Kosgei, J.; Mutai, C.; Kimoloi, S. Ethnomedicinal Uses of Stingless Bee Honey among Native Communities of Baringo County, Kenya. Sci. Afr. 2022, 17, e01297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, M.C.; McCarter, J.; Mead, A.; Berkes, F.; Stepp, J.R.; Peterson, D.; Tang, R. Defining Biocultural Approaches to Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P. (Ed.) The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations; TEEB—The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M.B. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.1 and Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure; Fabis Consulting Ltd.: Nottingham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, J. Web of Science and Scopus Are Not Global Databases of Knowledge. Eur. Sci. Ed. 2020, 46, e51987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. 2005, pp. 1–137. Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Gould, R.; Satterfield, T. Critiques of Cultural Ecosystem Services, and Ways Forward That Minimize Them. In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Ecosystem Services; Taylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2025; pp. 13–25. ISBN 978-1-003-41489-6. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of Cultural Services to the Ecosystem Services Agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking Ecosystem Services to Better Address and Navigate Cultural Values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Kirsop, B.; Arunachalam, S. Towards Open and Equitable Access to Research and Knowledge for Development. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, Mapping, and Quantifying Cultural Ecosystem Services at Community Level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengberg, A.; Fredholm, S.; Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Saltzman, K.; Wetterberg, O. Cultural Ecosystem Services Provided by Landscapes: Assessment of Heritage Values and Identity. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Novel Framework for Research and Critical Engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.M.; Antonini, Y. The Traditional Knowledge on Stingless Bees (Apidae: Meliponina) Used by the Enawene-Nawe Tribe in Western Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, F.F.; Hilgert, N.I.; Lupo, L.C. Melliferous Insects and the Uses Assigned to Their Products in the Northern Yungas of Salta, Argentina. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyeltshen, T.; Bhatta, C.P.; Gurung, T.; Dorji, P.; Tenzin, J. Ethno-Medicinal Uses and Cultural Importance of Stingless Bees and Their Hive Products in Several Ethnic Communities of Bhutan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldasoro Maya, E.M.; Rodríguez Robles, U.; Martínez Gutiérrez, M.; Mutul, G.; Avilez López, T.; Morales, H.; Ferguson, B.; Rivas, J. Stingless Bee Keeping: Biocultural Conservation and Agroecological Education. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6, 1081400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Morsello, C.; Reyes-García, V.; De Faria, R.B.M. Children’s Use of Time and Traditional Ecological Learning. A Case Study in Two Amazonian Indigenous Societies. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2013, 27, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Khan, S. Traditional Ecological Knowledge Sustains Due to Poverty and Lack of Choices Rather than Thinking about the Environment. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, K.L.W.; Fitzpatrick, Ú.; Stanley, D.A. Public Perceptions of Ireland’s Pollinators: A Case for More Inclusive Pollinator Conservation Initiatives. J. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 61, 125999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisante, F.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Arnold, S.E.J.; Belmain, S.R.; Gurr, G.M.; Darbyshire, I.; Xie, G.; Tumbo, J.; Stevenson, P.C. Enhancing Knowledge among Smallholders on Pollinators and Supporting Field Margins for Sustainable Food Security. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.S.; Forister, M.L.; Carril, O.M. Interest Exceeds Understanding in Public Support of Bee Conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; Corrigan, S. Bee Well: A Positive Psychological Impact of a pro-Environmental Intervention on Beekeepers’ and Their Families’ Wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1354408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesur, E. A Creative Approach in Creative Tourism: Apitourism. In Tourism Studies and Social; University Press St. Kliment Ohridski: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021; pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Noguer-Juncà, E.; Crespi-Vallbona, M. Bee Tourism: Apiculture and Sustainable Development in Rural Areas. J. Apic. Res. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Jamal, T. Slow Food Tourism: An Ethical Microtrend for the Anthropocene. J. Tour. Futur. 2020, 6, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Gascón, M.; Rubio-Gil, Á. Theoretical Approach to Api-Tourism Routes as a Paradigm of Sustainable and Regenerative Rural Development. J. Apic. Res. 2023, 62, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuligoj, M. Origins and Development of Apitherapy and Apitourism. J. Apic. Res. 2021, 60, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, E.; Adamchuk, L.; Negri, I.; Kösoğlu, M.; Papa, G.; Dârjan, M.S.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Mărgăoan, R. Traces of Honeybees, Api-Tourism and Beekeeping: From Past to Present. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Y.; Maya, E.M.; Rosset, P.; Morales, H.; Vides, E. Meliponiculturas Contemporáneas En Nicaragua: Desafíos y Oportunidades Desde La Agroecología. La Calera 2024, 24, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calboli, I.; Ng-Loy, W.L. Geographical Indications at the Crossroads of Trade, Development, and Culture: Focus on Asia-Pacific; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; ISBN 978-1-316-71100-2.

- Adebola, T. The Legal Construction of Geographical Indications in Africa. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2023, 26, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.; Halteman, P.; Kaechele, N.; Satterfield, T. Methods for Assessing Social and Cultural Losses. Science 2023, 381, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satz, D.; Gould, R.K.; Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.; Norton, B.; Satterfield, T.; Halpern, B.S.; Levine, J.; Woodside, U.; Hannahs, N.; et al. The Challenges of Incorporating Cultural Ecosystem Services into Environmental Assessment. AMBIO 2013, 42, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Héger, M.; Noiset, P.; Nkoba, K.; Vereecken, N.J. Beyond Nutrition: A novel hierarchical framework for the study of Traditional Ecological Knowledge associated with Stingless Bee Honeys. 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Mujere, N.; Chanza, N.; Muromo, T.; Guurwa, R.; Kutseza, N.; Mutiringindi, E. Indigenous Ways of Predicting Agricultural Droughts in Zimbabwe. In Socio-Ecological Systems and Decoloniality: Convergence of Indigenous and Western Knowledge; Pullanikkatil, D., Hughes, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 51–72. ISBN 978-3-031-15097-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X. A Review of Empirical Studies of Cultural Ecosystem Services in National Parks: Current Status and Future Research. Land 2023, 12, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, F.; Dehghani, A.; Ratansiri, A.; Ghaffari, M.; Raina, S.K.; Halimi, A.; Rakhshanderou, S.; Ismael, S.A.; Amiri, P.; Aminafshar, A.; et al. ChecKAP: A Checklist for Reporting a Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 25, 2573–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElwee, P.; He, J.; Hsu, M. Challenges to Understanding and Managing Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Global South. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vereecken, N.J.; Héger, M.; Aganze Mweze, M.; Razakamiaramanana, A.; Karanja, R.H.N.; Nkoba, K.; Noiset, P. Afrotropical Stingless Bees Illustrate a Persistent Cultural Blind Spot in Research, Policy and Conservation. Diversity 2025, 17, 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120826

Vereecken NJ, Héger M, Aganze Mweze M, Razakamiaramanana A, Karanja RHN, Nkoba K, Noiset P. Afrotropical Stingless Bees Illustrate a Persistent Cultural Blind Spot in Research, Policy and Conservation. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120826

Chicago/Turabian StyleVereecken, Nicolas J., Madeleine Héger, Marcelin Aganze Mweze, Aina Razakamiaramanana, Rebecca H. N. Karanja, Kiatoko Nkoba, and Pierre Noiset. 2025. "Afrotropical Stingless Bees Illustrate a Persistent Cultural Blind Spot in Research, Policy and Conservation" Diversity 17, no. 12: 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120826

APA StyleVereecken, N. J., Héger, M., Aganze Mweze, M., Razakamiaramanana, A., Karanja, R. H. N., Nkoba, K., & Noiset, P. (2025). Afrotropical Stingless Bees Illustrate a Persistent Cultural Blind Spot in Research, Policy and Conservation. Diversity, 17(12), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120826