Ornamental Plant Diversity and Traditional Uses in Home Gardens of Kham Toei Sub-District, Thai Charoen District, Yasothon Province, Northeastern Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Which ornamental plant species are perceived as culturally significant in Kham Toei Sub-district?

- (2)

- What functions—whether esthetic, ritual, edible, or health-related—are associated with these species?

- (3)

- How do availability, perceived utility, and cultural context shape local valuations of ornamental plants?

2. Materials and Methods

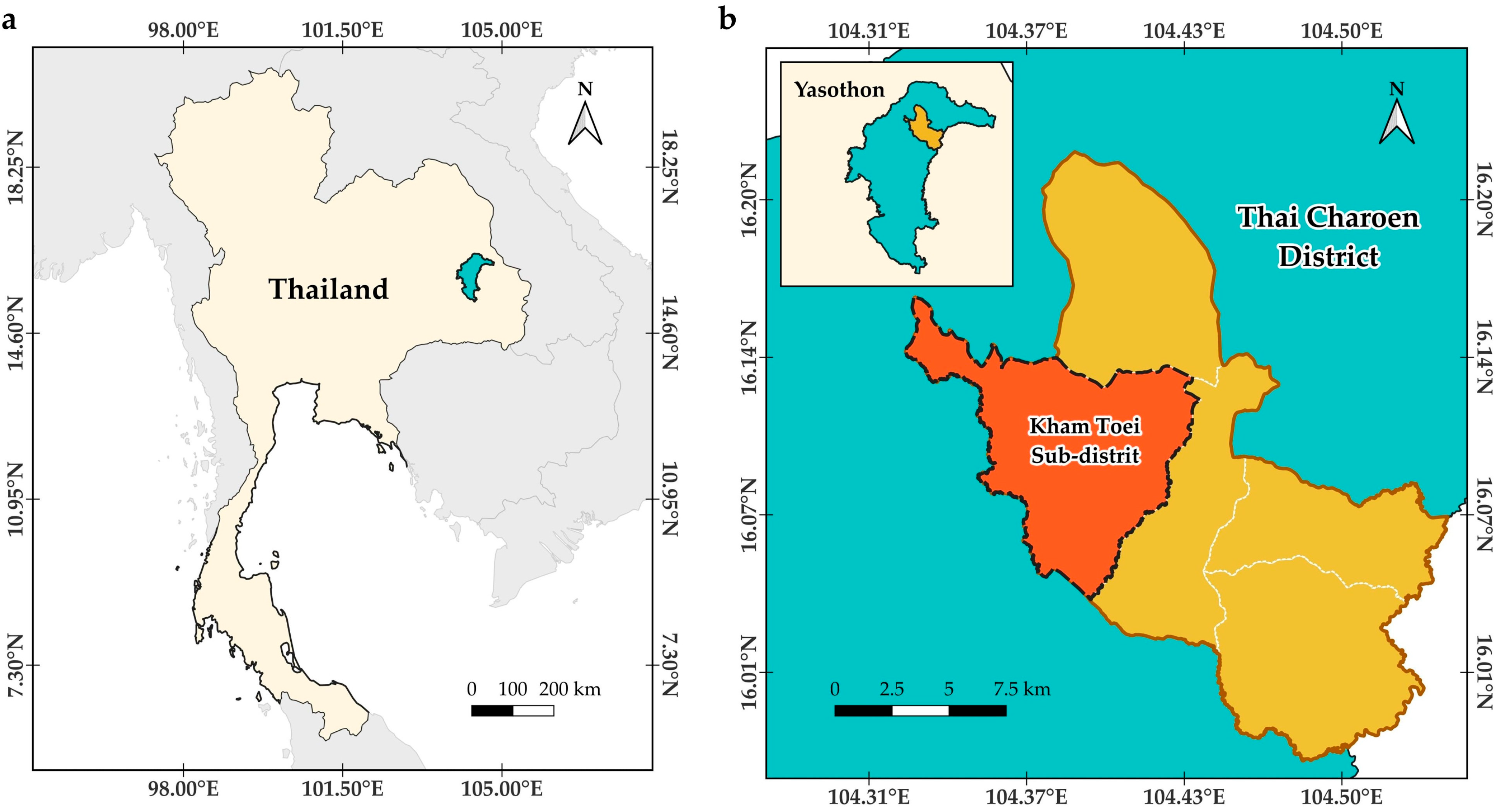

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Survey and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Cultural Ornamental Significance Index (COSI)

2.3.2. Plant Part Value (PPV)

2.3.3. Fidelity Level (%FL)

2.3.4. Informant Consensus Factor (FIC)

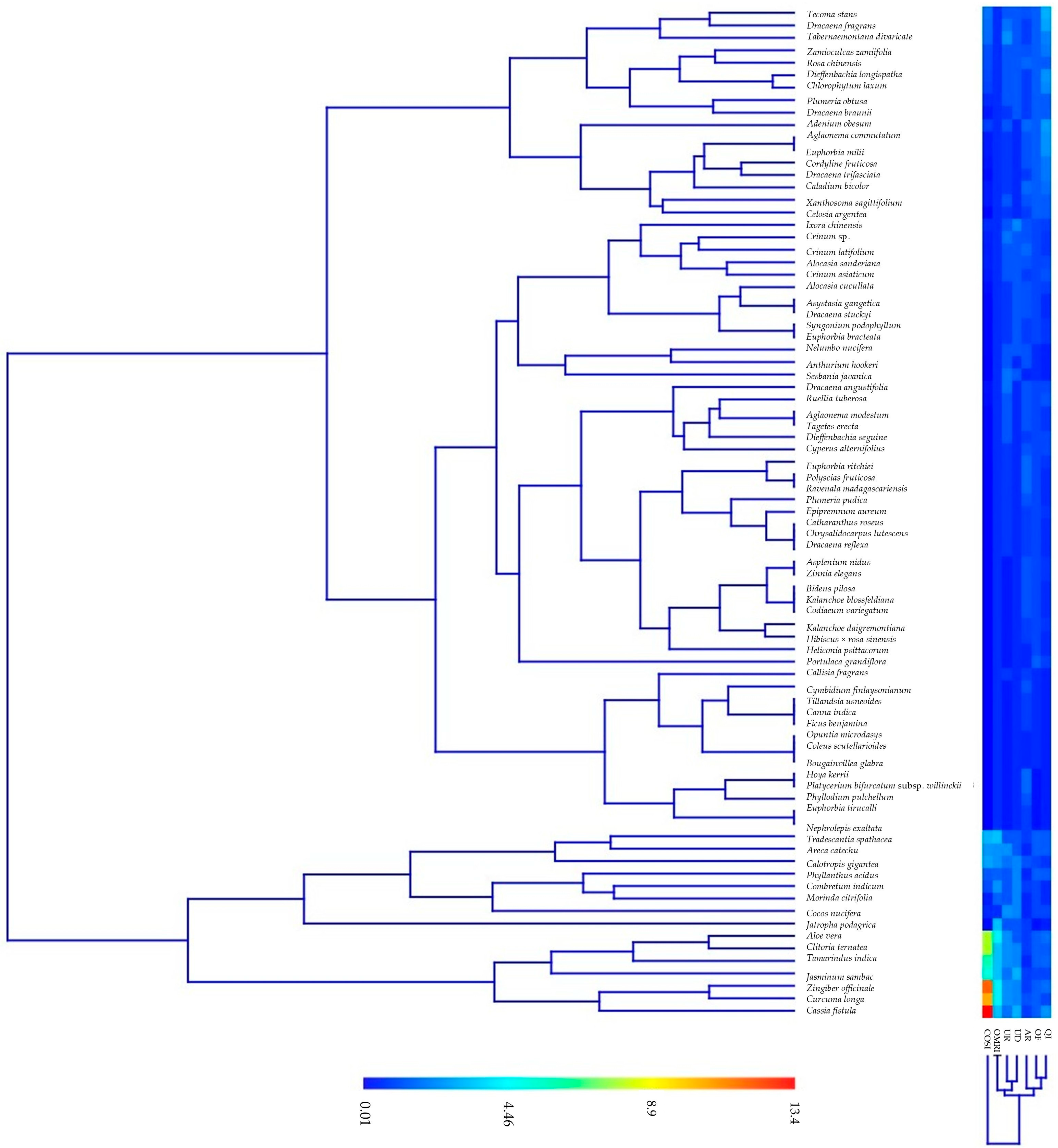

2.3.5. Cluster Analysis

3. Results

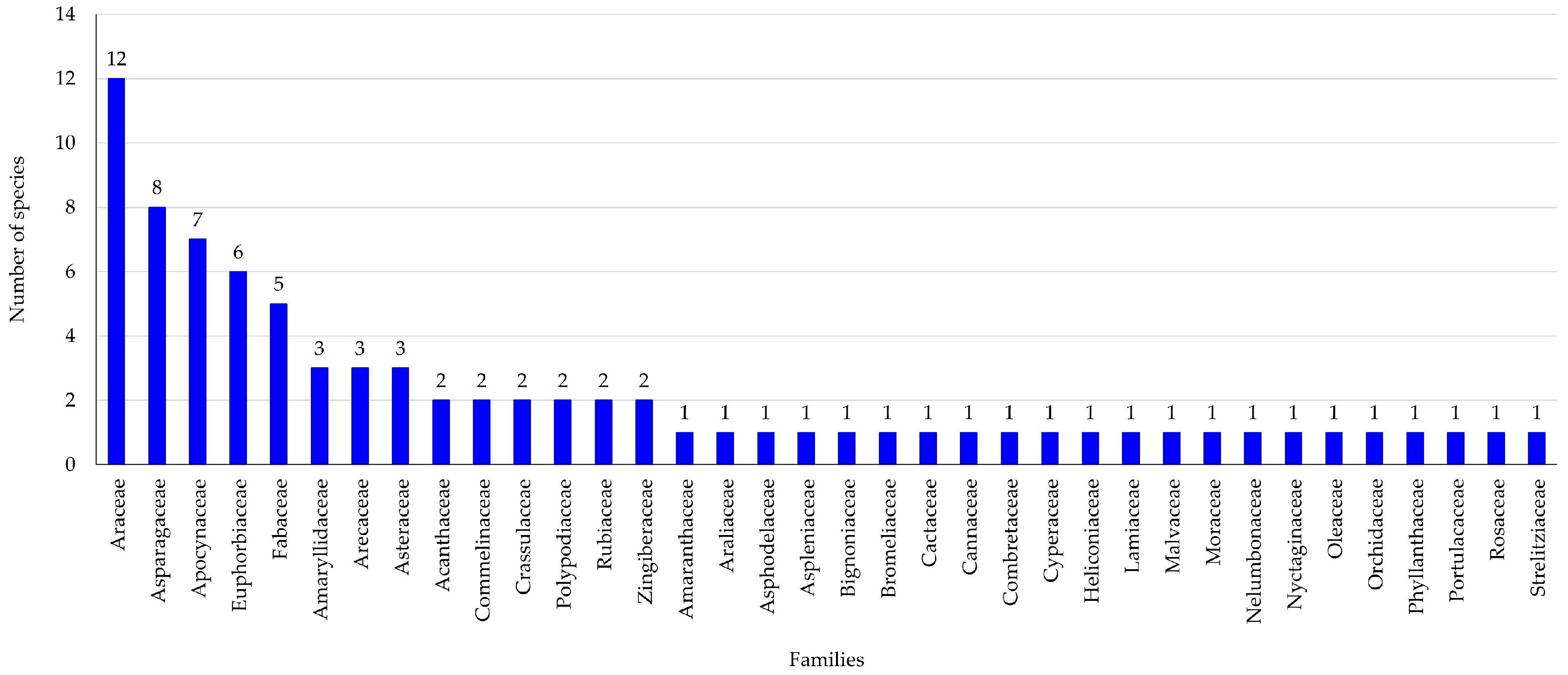

3.1. Ornamental Plants Diversity, Origin and Life Forms in Kham Toei Sub-District

3.2. Cultural Ornamental Significance Index (COSI) in Kham Toei Sub-District

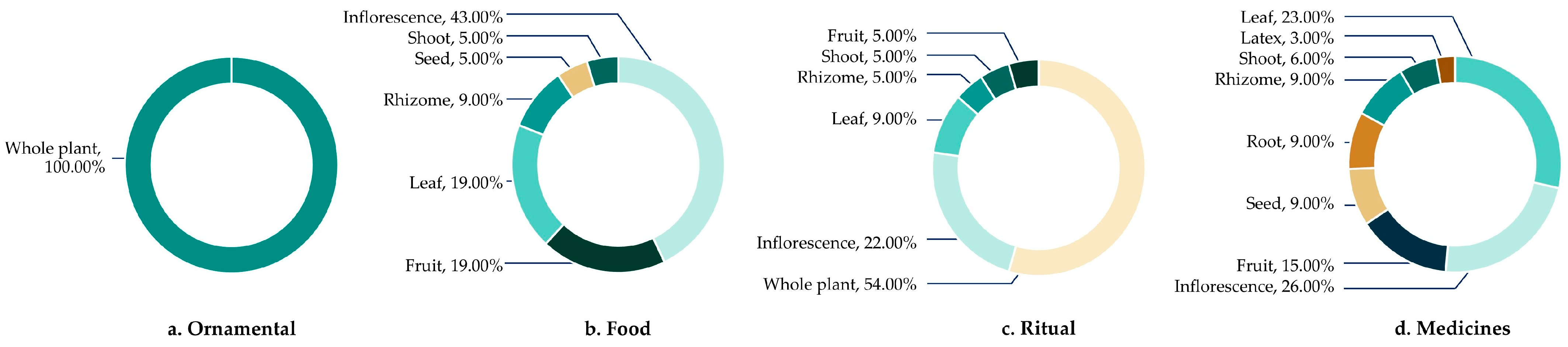

3.3. Other Utilization of Ornamental Plants in Kham Toei Sub-District

3.4. Fidelity Level (%FL) of Ornamental Plants in Kham Toei Sub-District

3.5. Informant Consensus Factor (FIC) of Ornamental Plants in Kham Toei Sub-District

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity and Structural Composition of Ornamental Plants

4.2. Cultural Significance of Ornamental Plants

4.3. Traditional and Cultural Roles of Ornamental Plants

4.4. Medicinal Significance of Ornamental Plants

4.5. Novelty of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Francini, A.; Romano, D.; Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A. The Contribution of Ornamental Plants to Urban Ecosystem Services. Earth 2022, 3, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwardi, A.B.; Navia, Z.I.; Sutrisno, I.H.; Elisa, H.; Efriani. Ethnobotany of ritual plants in Malay culture: A case study of the Sintang community, Indonesia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2025, 30, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlóci, L.; Fekete, A. Ornamental Plants and Urban Gardening. Plants 2023, 12, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguanchoo, V.; Balslev, H.; Sadgrove, N.J.; Phumthum, M. Medicinal plants used by rural Thai people to treat non-communicable diseases and related symptoms. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsasilp, A.; Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S. Ginger family from Bueng Kan Province, Thailand: Diversity, conservation status, and traditional uses. Biodiversitas 2022, 23, 2739–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamngon, P.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Junsongduang, A. Ethnobotanical knowledge of Isaan Laos tribe in Khong Chai District, Kalasin Province, Thailand with particular focus on medicinal uses. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 6793–6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamngon, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Junsongduang, A. Ethnobotanical of the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Pho Chai District, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 8, 6152–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, C.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R.; He, L.; Zheng, W. Ornamental plants associated with Buddhist figures in China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguenon, M.P.P.; Gbesso, G.H.F.; Godonou, E.R.A. Ethnobotanical analysis of ornamental plant producers’ knowledge in Benin: Valorization and management perspectives. Ornam. Hortic. 2024, 30, e242736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liang, X.; Xie, J.; Wu, F. Ethnobotany of wild edible plants in multiethnic areas of the Gansu–Ningxia–Inner Mongolia junction zone. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareef, H.; Gul, M.T.; Qureshi, R.; Aati, H.; Munazir, M. Application of ethnobotanical indices to document the use of plants in traditional medicines in Rawalpindi district, Punjab-Pakistan. Ethnob. Res. Appl. 2023, 25, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, A.; Shennan, S.; Odling-Smee, J. Ornamental plant domestication by aesthetics-driven human cultural niche construction. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 1360–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2023. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Khamtoei Tambon Administration Organization. Khamtoei Subdistrict: General Information. Available online: https://www.khamtoei-yst.go.th/tambon/general (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Tourism Authority of Thailand. Ban Song Yae Catholic Church (The Archangel Michael’s Church). Available online: https://www.tourismthailand.org/Attraction/ban-song-yae-catholic-church-the-archangel-michael-s-church (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Tajik, O.; Golzar, J.; Noor, S. Purposive Sampling. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Stud. 2024, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant of the World Online, Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE). International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 Additions). 2006. Available online: http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from Their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity. United Nations, Montreal. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Pieroni, A. Evaluation of the cultural significance of wild food botanicals traditionally consumed in northwestern Tuscany, Italy. J. Ethnobiol. 2001, 21, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Beloz, A. Plant use knowledge of the Winikina Warao: The case for questionnaires in ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 2002, 56, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Yaniv, Z.; Dafni, A.; Palewitch, D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 16, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneath, P.H.A.; Sokal, R.R. Numerical Taxonomy; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Castillón, E.; Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.Á.; Cuéllar-Rodríguez, L.G.; March-Salas, M.; Encina-Domínguez, J.A.; Himmeslbach, W.; Salinas-Rodríguez, M.M.; Guerra, J.; Cotera-Correa, M.; Scott-Morales, L.M.; et al. Ethnobotany in Iturbide, Nuevo León: The Traditional Knowledge on Plants Used in the Semiarid Mountains of Northeastern Mexico. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croat, T.B.; Ortiz, O.O. Distribution of Araceae and the Diversity of Life Forms. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2020, 89, 8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-F.; Wang, J.; Dong, R.; Zhu, H.-W.; Lan, L.-N.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Li, N.; Deng, C.-L.; Gao, W.-J. Chromosome-level genome assembly, annotation and evolutionary analysis of the ornamental plant Asparagus setaceus. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S. Multipurpose Ornamental Plant Plumeria rubra Linn (Apocynaceae). Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 2, 646. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.J.; Francia, R.M. Plant traits, microclimate temperature and humidity: A research agenda for advancing nature-based solutions to a warming and drying climate. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpelainen, H. The Role of Home Gardens in Promoting Biodiversity and Food Security. Plants 2023, 12, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monder, M.J.; Pacholczak, A.; Zajączkowska, M. Directions in Ornamental Herbaceous Plant Selection in the Central European Temperate Zone in the Time of Climate Change: Benefits and Threats. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Esperon-Rodriguez, M.; St-Denis, A.; Tjoelker, M.G. Native vs. Non-Native Plants: Public Preferences, Ecosystem Services, and Conservation Strategies for Climate-Resilient Urban Green Spaces. Land 2025, 14, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, E.S.; Aronson, M.F. Plant native: Comparing biodiversity benefits, ecosystem services provisioning, and plant performance of native and non-native plants in urban horticulture. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 2587–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, R. Native Plants in Urban Landscapes: A Biological Imperative. Nativ. Plants J. 2020, 21, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Ma, X.; Hu, Q.; Feng, L.; Hu, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J. The Ecological Risks and Invasive Potential of Introduced Ornamental Plants in China. Plants 2025, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguanchoo, V.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Balslev, H.; Inta, A. Exotic Plants Used by the Hmong in Thailand. Plants 2019, 8, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardberger, A.; Craig, D.; Simpson, C.; Cox, R.D.; Perry, G. Greening up the City with Native Species: Challenges and Solutions. Diversity 2025, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathoure, A.K. Cultural Practices to Protecting Biodiversity Through Cultural Heritage: Preserving Nature, Preserving Culture. Biodivers. Int. J. 2024, 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Khanam, H.; Pandey, J. The Biological Properties and Medical Importance of Cassia fistula: A Mini Review. Chem. Proc. 2023, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Iglesias, I.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Pharmacological Update Properties of Aloe vera and its Major Active Constituents. Molecules 2020, 25, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, M.C.N.; Munisih, S. Medicinal usage of Clitoria ternatea flower petal: A narrative review. BIS Health Environ. Sci. 2025, 2, V225002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyamo, D. Dieffenbachia plant poisoning requiring mechanical ventilation: A case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2025, 19, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, D.R.; Brown, I.; Okojie, I.G. Sub-acute toxicity of Caladium bicolor (Aiton) leaf extract in Wistar rats. J. Phytol. 2020, 12, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erawan, T.S.; Alillah, A.N.; Iskandar, J. Ethnobotany of ritual plants in Karangwangi Village, Cianjur District, West Java, Indonesia. Asian J. Ethnobiol. 2018, 1, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.; Kapare, H.; Gargate, N. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological aspects on Tabernaemontana divaricata plant. Acta Sci. Pharmacol. 2022, 3, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Al Yamini, T.H.; Djuita, N.R.; Chikmawati, T.; Purwanto, Y. Ethnobotany of wild and semi-wild edible plants of the Madurese Tribe in Sampang and Pamekasan Districts, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Serrano, V.; Onaindia, M.; Alday, J.G.; Caballero, D.; Carrasco, J.C.; McLaren, B.; Amigo, J. Plant diversity and ecosystem services in Amazonian homegardens of Ecuador. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 225, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Yu, M.; Yao, Z. Ethnobotanical study on factors influencing plant composition and traditional knowledge in homegardens of Laifeng Tujia ethnic communities, the hinterland of the Wuling mountain area, central China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustina, T.P.; Hasmiati; Rukmana, M.; Watung, F.A. Ethnobotany and the structure of Home garden in Pujon Sub-distict Malang Regency, East Java Indonesia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattiglia, G.; Rattighieri, E.; Clò, E.; Anichini, F.; Campus, A.; Rossi, M.; Buonincontri, M.; Mercuri, A.M. Palynology of Gardens and Archaeobotany for the Environmental Reconstruction of the Charterhouse of Calci-Pisa in Tuscany (Central Italy). Quaternary 2023, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihn, A.L.; Knuth, M.J.; Behe, B.K.; Hall, C.R. Benefit Information’s Impact on Ornamental Plant Value. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabar, M.A.; Falah, B.H.; Andini, P.I.; Kartika, E. Ethnobotanical studies in the ritual of Panjang Jimat ceremony at the Kasepuhan Palace Cirebon. In Proceedings of the Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta Graduate Conference, Virtual, 22 August 2024; Volume 3, pp. 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Luo, D.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, G. Ethnobotanical study on ritual plants used by Hani people in Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saising, J.; Maneenoon, K.; Sakulkeo, O.; Limsuwan, S.; Götz, F.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P. Ethnomedicinal Plants in Herbal Remedies Used for Treatment of Skin Diseases by Traditional Healers in Songkhla Province, Thailand. Plants 2022, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Sun, J.; Bi, Z.; Xia, S.; Xiong, Y.; Bai, X.; Huang, X. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Yi people in Mile, Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taek, M.M.; Banilodu, L.; Neonbasu, G.; Watu, Y.V.; Prajogo, B.E.W.; Agil, M. Ethnomedicine of Tetun ethnic people in West Timor Indonesia: Philosophy and practice in the treatment of malaria. Integr. Med. Res. 2019, 8, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Kisangani Kalonda, B.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Yona Mleci, J.; Mpibwe Kalenga, A.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Exploring Floristic Diversity, Propagation Patterns, and Plant Functions in Domestic Gardens Across Urban Planning Gradient in Lubumbashi, DR Congo. Ecologies 2024, 5, 512–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H.; Naeem, H.; Batool, N. Quantitative assessment of the ethnomedicinal knowledge of wild plants used to treat human ailments. Vegetos 2025, 38, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonti, M. The relevance of quantitative ethnobotanical indices for ethnopharmacology and ethnobotany. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 288, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakurel, D.; Uprety, Y.; Ahn, G.; Cha, J.-Y.; Kim, W.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Rajbhandary, S. Diversity, Distribution, and Sustainability of Traditional Medicinal Plants in Kaski District, Western Nepal. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1076351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Scientific Name | Used Part | Method of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Asystasia gangetica (L.) T.Anderson | Leaf, young shoot | Cooked as a leafy vegetable, stir-fried or boiled |

| 2. | Cassia fistula L. | Flower | Flowers cooked in curries |

| 3. | Clitoria ternatea L. | Flower | Used as a natural food colorant in rice, desserts, and drinks; eaten fresh as beverage |

| 4. | Cocos nucifera L. | Endosperm (coconut flesh), water, inflorescence sap | Eaten fresh, grated for cooking, coconut water as beverage, sap for sugar or drink |

| 5. | Combretum indicum (L.) DeFilipps | Flower | Consumed fresh or used to flavor beverages |

| 6. | Ixora chinensis Lam. | Flower | Used fresh in traditional desserts or eaten raw |

| 7. | Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton | Flower | Used to flavored tea, desserts, and beverages |

| 8. | Morinda citrifolia L. | Fruit, leaf | Ripe fruits eaten fresh or processed as juice; young leaves cooked as vegetable |

| 9. | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. | Rhizome, seed, young leaf | Rhizomes boiled or stir-fried, seeds eaten fresh or roasted, young leaves used for wrapping food |

| 10. | Phyllanthus acidus (L.) Skeels | Fruit, leaf | Fruits eaten fresh, pickled, or in preserves; leaves sometimes used as vegetable |

| 11. | Rosa chinensis Jacq. | Flower | Petals used in teas, desserts, or syrups |

| 12. | Sesbania javanica Miq. | Flower | Flowers eaten fresh in salads or cooked |

| 13. | Tamarindus indica L. | Fruit, young leaf, flower | Pulp used in beverages, sauces, and curries; young leaves and flowers used in soups |

| 14. | Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | Flower | Occasionally consumed fresh or used as garnish in salads |

| 15. | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Rhizome | Used as spice, condiment, tea, and in curries |

| No. | Scientific Name | Used Part | Method of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alocasia cucullata (Lour.) G.Don | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 2. | Alocasia sanderiana W.Bull | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 3. | Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton | Flower | Used in traditional ceremonial arrangements (bai sri) for worship and rituals such as weddings, ordinations, and spirit-calling ceremonies. |

| 4. | Cassia fistula L. | Leaf, shoot | Leaves are used in major ceremonies such as the city pillar ritual; heartwood is part of ceremonial betel sets used in the worship of deities. |

| 5. | Chlorophytum laxum R.Br. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 6. | Cocos nucifera L. | Fruit | Used in religious and spiritual ceremonies. |

| 7. | Crinum asiaticum L. | Leaf | Mixed into holy water to dispel evil spirits. |

| 8. | Crinum latifolium L. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 9. | Crinum sp. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 10. | Curcuma longa L. | Rhizome | Mixed into holy water for bathing Buddha images or elders during rituals. |

| 11. | Dieffenbachia longispatha Engl. & K.Krause | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 12. | Dracaena braunii Engl. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 13. | Dracaena fragrans (L.) Ker Gawl. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 14. | Dracaena stuckyi (God.-Leb.) Byng & Christenh. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 15. | Euphorbia bracteata Jacq. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 16. | Ixora chinensis Lam. | Flower | Used in traditional ceremonial arrangements (bai sri) for worship and rituals such as weddings, ordinations, and spirit-calling ceremonies. |

| 17. | Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton | Flower | Mixed into holy water for bathing Buddha images or elders during rituals. |

| 18. | Plumeria obtusa L. | Flower | Used in traditional ceremonial arrangements (bai sri) for worship and rituals such as weddings, ordinations, and spirit-calling ceremonies. |

| 19. | Syngonium podophyllum Schott | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| 20. | Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult. | Flower | Used in traditional ceremonial arrangements (bai sri) for worship and rituals such as weddings, ordinations, and spirit-calling ceremonies. |

| 21. | Zamioculcas zamiifolia (G.Lodd.) Engl. | Whole plant | Believed in attracting wealth, fortune, and prosperity. |

| No. | Scientific Name | FL | Used Parts | CoP | Preparation | Medicinal Properties | RoA | Therapeutic Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | 60.00 | Leaf | Fresh | The leaf is peeled and carefully cleansed to eliminate the mucilaginous layer, after which the transparent gel is directly applied to treat wounds | Traditionally used to promote wound healing and to treat abscesses and inflammatory conditions | Dermal | Skin System |

| 40.00 | Leaf | Fresh | Fresh leaves are peeled, the mucilage removed, and the clear gel blended to prepare a refreshing traditional beverage | Traditionally employed to relieve bruises and to facilitate wound healing | Oral | Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases | ||

| 2. | Areca catechu L. | 66.67 | Leaf | Fresh | The plant is boiled with water, and the decoction is used for bathing | The plant is traditionally used to reduce body heat, alleviate fever, and relieve symptoms of the common cold | Dermal | Infection, Parasite and Immune System |

| 33.33 | Seed | Dry | The plant parts are sun-dried, ground into powder, and infused in hot water to prepare a traditional herbal infusion for oral consumption | Traditionally used as an anthelmintic remedy to expel intestinal parasites such as roundworms, tapeworms, and liver flukes | Dermal | Infection, Parasite and Immune System | ||

| 3. | Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton | 57.14 | Inflorescence | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used as an antipyretic remedy to reduce fever | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune System |

| 42.86 | Shoot | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used as an expectorant to relieve phlegm and respiratory congestion | Oral | Gastrointestinal | ||

| 4. | Cassia fistula L. | 50.00 | Inflorescence | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used as an antipyretic remedy to reduce fever | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune system |

| 37.50 | Inflorescence | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used to stop bleeding and treat hemorrhagic conditions | Oral | Obstetrics, Gynecology and Urinary Disorders | ||

| 12.50 | Root | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used to treat cardiovascular disorders | Oral | Cardiovascular System | ||

| 5. | Clitoria ternatea L. | 37.50 | Inflorescence | Fresh | The flower petals are crushed to obtain the juice, which is then ingested as a traditional beverage | Traditionally used to strengthen vision and alleviate symptoms such as blurred or watery eyes | Oral | Eye Disorders |

| 37.50 | Inflorescence | Fresh | Traditionally consumed fresh/raw. | Traditionally used to prevent and alleviate numbness or tingling sensations in the fingers and toes. | Oral | Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases | ||

| 25.00 | Inflorescence | Fresh | Traditionally incorporated as an ingredient in cosmetic and personal care products, including hair conditioners and shampoos | Traditionally used to stimulate hair growth and enhance hair pigmentation | Dermal | Skin System | ||

| 6. | Combretum indicum (L.) DeFilipps | 57.14 | Seed | Dry | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used as an anthelmintic to eliminate roundworms and intestinal worms | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune System |

| 42.86 | Leaf | Fresh | The plant material is crushed and applied topically as a poultice on the affected skin area | Traditionally used to promote wound healing and to treat abscesses and inflammatory conditions | Dermal | Skin System | ||

| 7. | Curcuma longa L. | 50.00 | Rhizome | Dry | Dried, powdered, mixed with honey, and pressed into pills | Traditionally used to relieve bloating, flatulence, abdominal discomfort, and indigestion | Oral | Gastrointestinal |

| 50.00 | Rhizome | Dry | Dried, powdered, mixed with honey, and pressed into pills | Traditionally used to treat dyspepsia (indigestion), including symptoms such as bloating, nausea, and abdominal discomfort | Oral | Gastrointestinal | ||

| 8. | Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton | 37.50 | Inflorescence | Dry | The plant is sun-dried, boiled in water, and the filtered liquid is consumed as a drink or prepared as a herbal tea | Traditionally used to nourish the heart and maintain cardiovascular vitality | Oral | Cardiovascular System |

| 37.50 | Root | Fresh | The plant material is pounded and combined with water, then consumed orally | Traditionally used to alleviate skin itching and to promote healing of chronic wounds | Dermal | Skin System | ||

| 25.00 | Leaf | Fresh | The plant material is finely pounded and combined with coconut oil, then gently heated before being applied topically to the affected skin area | Traditionally used to promote wound healing and to treat abscesses and inflammatory conditions | Dermal | Skin System | ||

| 9. | Jatropha podagrica Hook. | 80.00 | Shoot | Dry | The plant is sun-dried, boiled in water, and the filtered liquid is consumed as a drink | Traditionally used to enhance physical strength and overall vitality | Oral | Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases |

| 20.00 | Latex | Fresh | Wounds and abscesses are first cleaned thoroughly, and the plant extract or liquid is then applied directly to the affected area | Traditionally used to promote the healing of wounds—fresh, suppurating, and ulcerated—and to treat abscesses | Dermal | Skin System | ||

| 10. | Morinda citrifolia L. | 57.14 | Leaf | Dry | The plant is sun-dried, boiled in water, and the filtered liquid is consumed as a drink | Traditionally used to alleviate pain and discomfort in the wrists and ankles | Oral | Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases |

| 28.57 | Leaf | Dry | The plant is sun-dried, boiled in water, and the filtered liquid is consumed as a drink | Traditionally used to alleviate diarrhea, reduce coughing, facilitate phlegm expulsion, and relieve abdominal bloating and discomfort | Oral | Gastrointestinal | ||

| 14.29 | Inflorescence | Dry | The plant is sun-dried, boiled in water, and the filtered liquid is consumed as a drink or prepared as a herbal tea | Traditionally used to maintain heart health and prevent cardiovascular disorders | Oral | Cardiovascular System | ||

| 11. | Phyllanthus acidus (L.) Skeels | 71.43 | Fruit | Fresh | Traditionally consumed fresh/raw. | Traditionally used to alleviate fever and treat cough | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune System |

| 28.57 | Fruit | Fresh | Traditionally consumed fresh/raw. | Traditionally used to promote bowel movements as a natural laxative | Oral | Gastrointestinal | ||

| 12. | Tamarindus indica L. | 40.00 | Fruit | Fresh | Traditionally consumed fresh/raw. | Traditionally used to alleviate eye pain and discomfort | Oral | Eye Disorders |

| 30.00 | Fruit | Fresh | The seed coat is soaked in water, combined with sugar to impart a sweet taste, and the resulting liquid is consumed as a beverage | Traditionally used to alleviate fever and treat cough | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune System | ||

| 30.00 | Seed | Fresh | The seeds are roasted, the shells removed, and the seed kernels are soaked in salt water until soft before being eaten | Traditionally used to alleviate diarrhea and vomiting | Oral | Gastrointestinal | ||

| 13. | Tradescantia spathacea Sw. | 80.00 | Inflorescence | Dry | The plant is sun-dried, boiled in water, and the filtered liquid is consumed as a drink | Traditionally used to alleviate cough, sore throat, mouth ulcers, excessive thirst, and vomiting of blood | Oral | Gastrointestinal |

| 20.00 | Leaf | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, then combined with honey, lemon juice, and salt, and the resulting decoction is consumed orally | Traditionally used to alleviate symptoms of acid reflux | Oral | Gastrointestinal | ||

| 14. | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | 35.71 | Rhizome | Fresh | Traditionally consumed fresh/raw. | Traditionally employed as a restorative tonic to stimulate digestive fire and promote balance among bodily elements | Oral | Gastrointestinal |

| 28.57 | Fruit | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally administered to alleviate dryness of the throat and soothe sore throat | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune System | ||

| 21.43 | Root | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used to reduce phlegm and facilitate the clearing of respiratory passages | Oral | Infection, Parasite and Immune System | ||

| 14.29 | Inflorescence | Fresh | The plant is boiled in water, and the resulting decoction is filtered to obtain the liquid, which is then used | Traditionally used to alleviate urinary problems or act as a diuretic | Oral | Obstetrics, Gynecology and Urinary Disorders |

| Therapeutic Categories | Number of Use Report (Nur) | Number of Taxa (Nt) | FIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye Disorders | 7 | 2 | 0.83 |

| Infection, Parasite and Immune System | 33 | 7 | 0.81 |

| Gastrointestinal | 26 | 7 | 0.76 |

| Musculoskeletal and Joint Diseases | 13 | 4 | 0.75 |

| Obstetrics, Gynecology and Urinary Disorders | 5 | 2 | 0.75 |

| Skin System | 14 | 5 | 0.69 |

| Cardiovascular System | 5 | 3 | 0.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Sonthongphithak, P.; Jitpromma, T. Ornamental Plant Diversity and Traditional Uses in Home Gardens of Kham Toei Sub-District, Thai Charoen District, Yasothon Province, Northeastern Thailand. Diversity 2025, 17, 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120822

Saensouk P, Saensouk S, Chanthavongsa K, Sonthongphithak P, Jitpromma T. Ornamental Plant Diversity and Traditional Uses in Home Gardens of Kham Toei Sub-District, Thai Charoen District, Yasothon Province, Northeastern Thailand. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):822. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120822

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaensouk, Piyaporn, Surapon Saensouk, Khamfa Chanthavongsa, Phiphat Sonthongphithak, and Tammanoon Jitpromma. 2025. "Ornamental Plant Diversity and Traditional Uses in Home Gardens of Kham Toei Sub-District, Thai Charoen District, Yasothon Province, Northeastern Thailand" Diversity 17, no. 12: 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120822

APA StyleSaensouk, P., Saensouk, S., Chanthavongsa, K., Sonthongphithak, P., & Jitpromma, T. (2025). Ornamental Plant Diversity and Traditional Uses in Home Gardens of Kham Toei Sub-District, Thai Charoen District, Yasothon Province, Northeastern Thailand. Diversity, 17(12), 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120822