Prezygotic and Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibilities Complement Each Other in the Formation of a Cryptic Amphipod Species: The Example of a Lake Baikal Species Complex Eulimnogammarus verrucosus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

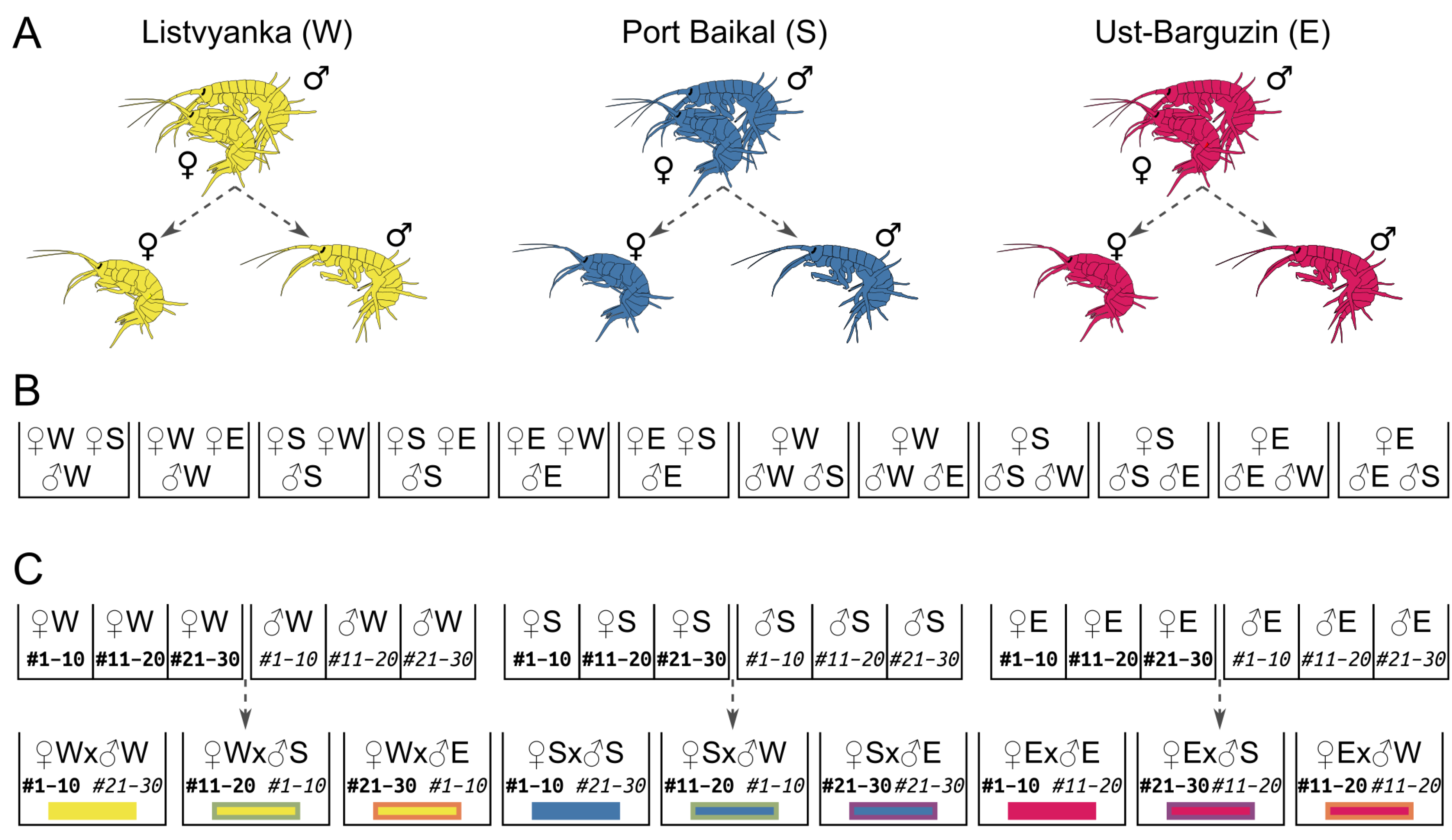

2.1. Study Object, Animal Sampling, and Experimental Design

2.2. Photographic and Microscopic Examination

2.3. Genotyping with PCR and Sanger Sequencing

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

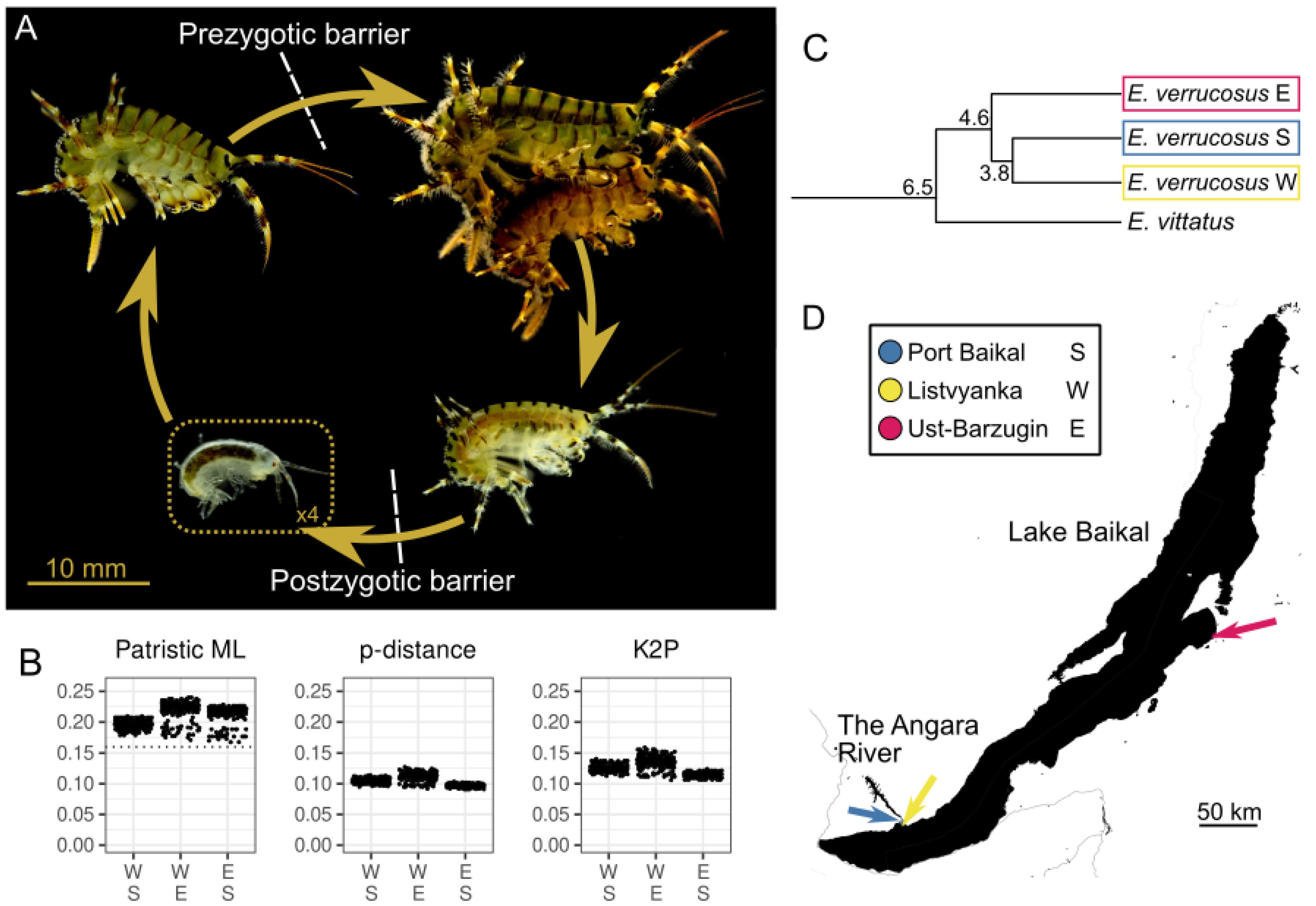

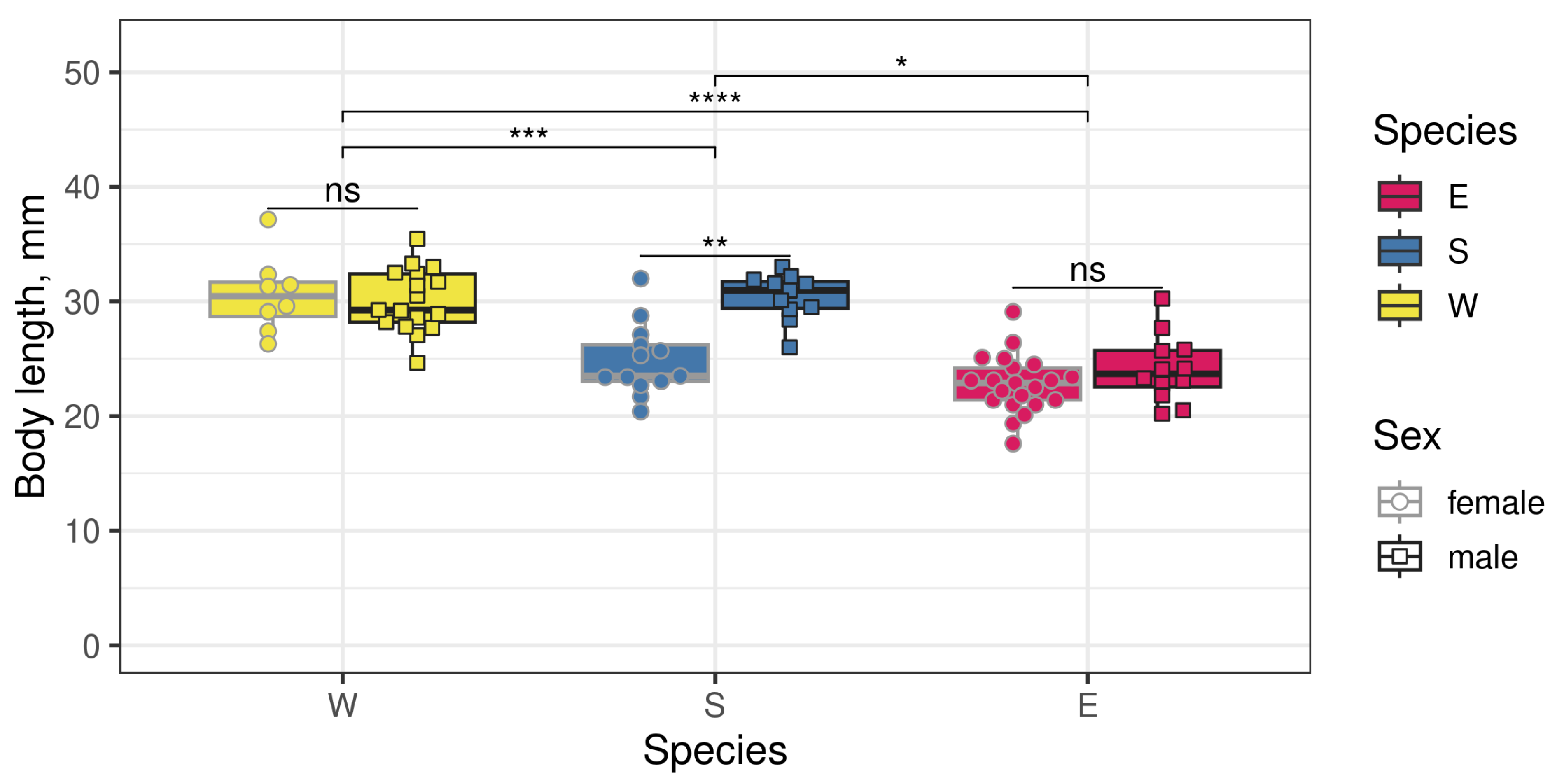

3.1. Three Biological Species Within the E. verrucosus Complex Differ in Size but Have Compatible Mating Seasons

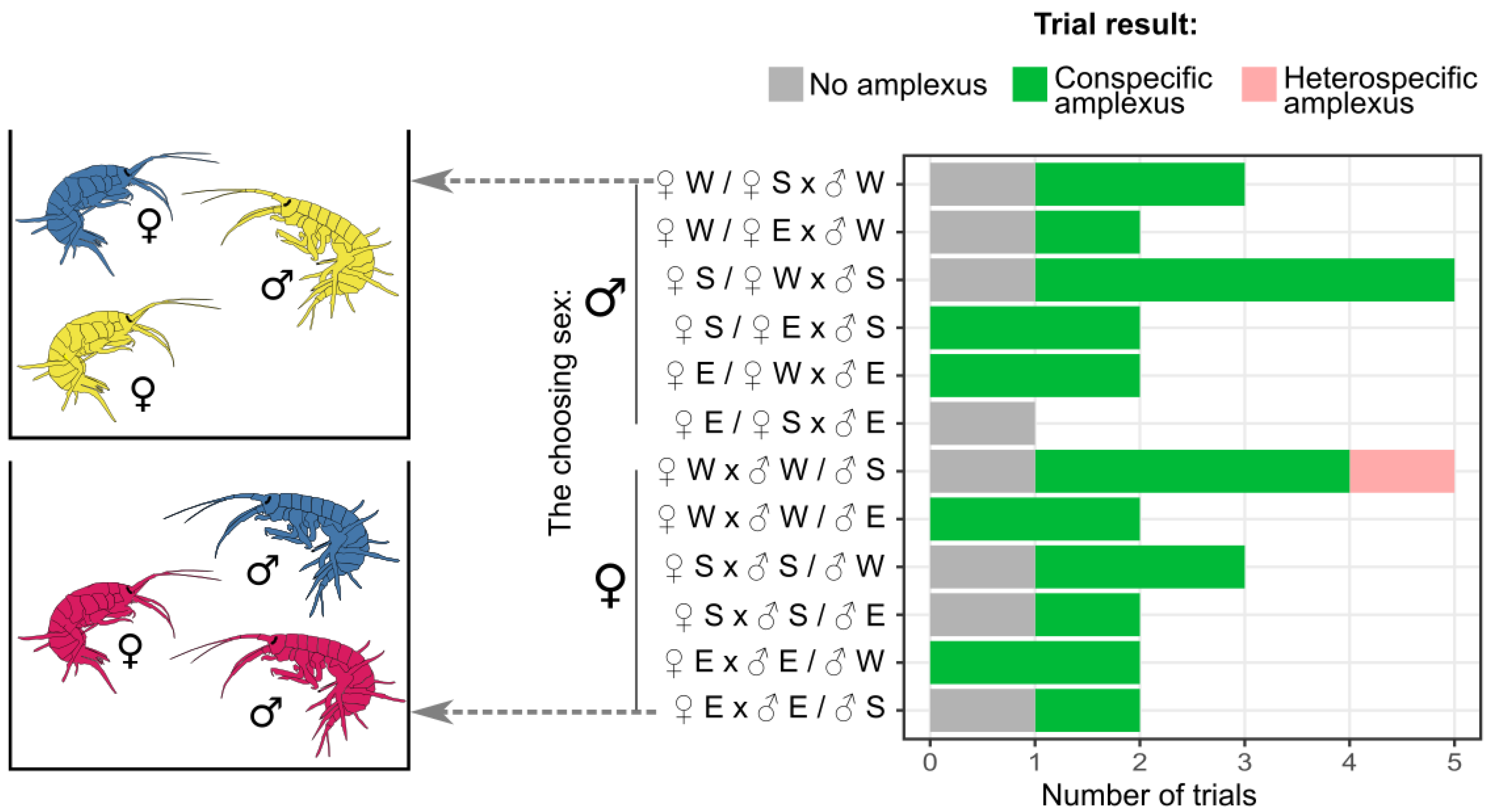

3.2. Mate Choice Trials Show Assortative Mating

3.3. No-Choice Mating Shows That Amplexus Formation Inversely Correlates with Genetic Difference

3.4. Development of Embryos from Hybrid Crosses Reveals Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibility Between Species

3.5. Juvenile Release Reveals That Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibility Is Not Absolute and That the Secondary Contact of Separated Species Already Occurs in Nature

4. Discussion

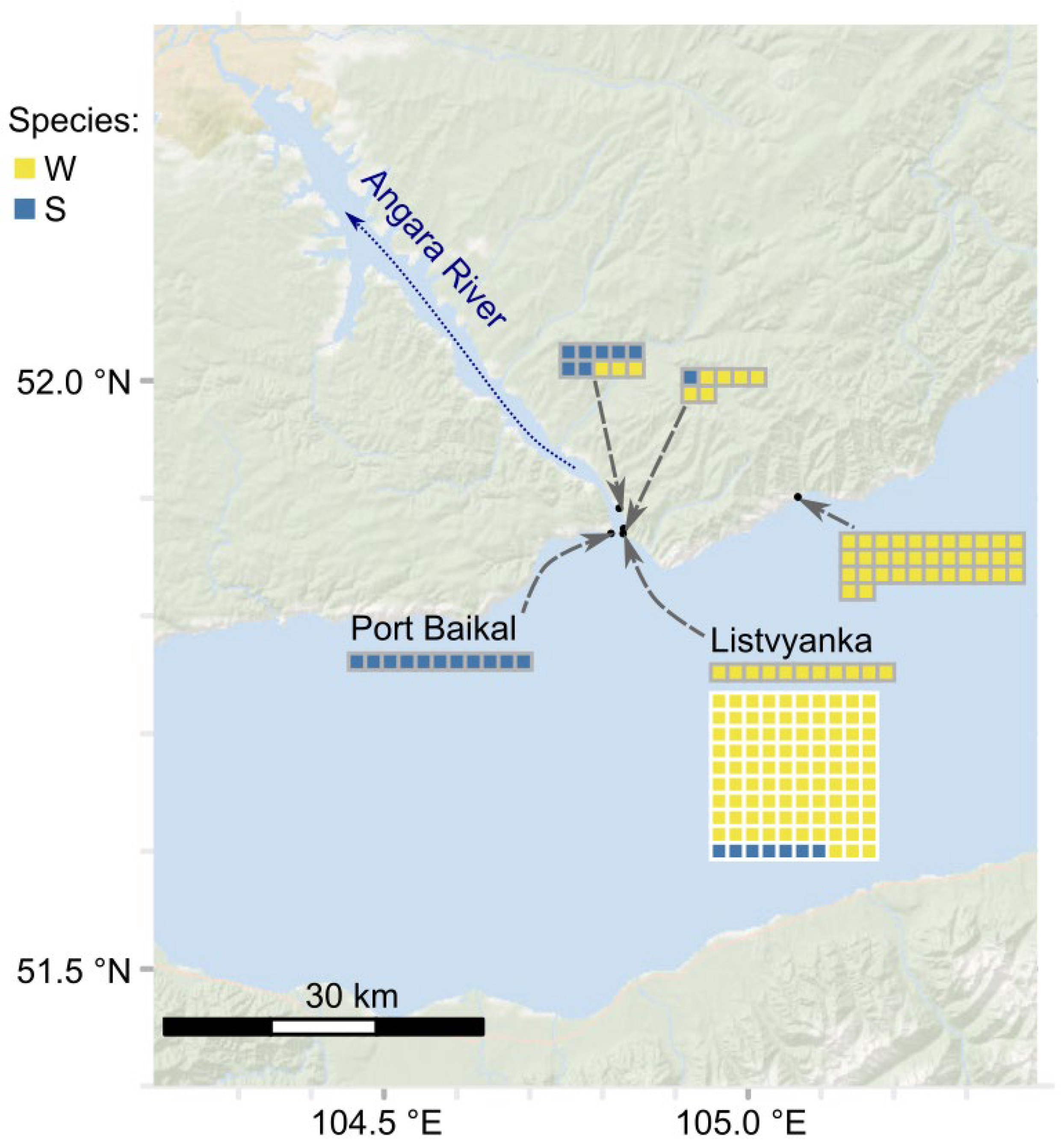

4.1. New Data on the Geographic Distribution of the Species of the E. verrucosus Species Complex

4.2. How Much Genetic Divergence Is Needed for Isolation?

4.3. The Fate of the Hybrid Embryos and the Physiology of Postzygotic Isolation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emerson, B.C. Delimiting Species—Prospects and Challenges for DNA Barcoding. Mol. Ecol. 2025, 34, e17677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, E. What Is a Species, and What Is Not? Philos. Sci. 1996, 63, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankowski, S.; Cutter, A.D.; Satokangas, I.; Lerch, B.A.; Rolland, J.; Smadja, C.M.; Segami Marzal, J.C.; Cooney, C.R.; Feulner, P.G.D.; Domingos, F.M.C.B.; et al. Toward the Integration of Speciation Research. Evol. J. Linn. Soc. 2024, 3, kzae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peichel, C.L.; Bolnick, D.I.; Brännström, Å.; Dieckmann, U.; Safran, R.J. Speciation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2025, 17, a041735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbstein, K.; Kösters, L.; Hodač, L.; Hofmann, M.; Hörandl, E.; Tomasello, S.; Wagner, N.D.; Emerson, B.C.; Albach, D.C.; Scheu, S.; et al. Species Delimitation 4.0: Integrative Taxonomy Meets Artificial Intelligence. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miralles, A.; Puillandre, N.; Vences, M. DNA Barcoding in Species Delimitation: From Genetic Distances to Integrative Taxonomy. In DNA Barcoding: Methods and Protocols; DeSalle, R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 77–104. ISBN 978-1-07-163581-0. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.D.; Gillis, D.J.; Hanner, R.H. Lack of Statistical Rigor in DNA Barcoding Likely Invalidates the Presence of a True Species’ Barcode Gap. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 859099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, M.L. The Promise of a DNA Taxonomy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefébure, T.; Douady, C.J.; Gouy, M.; Gibert, J. Relationship between Morphological Taxonomy and Molecular Divergence within Crustacea: Proposal of a Molecular Threshold to Help Species Delimitation. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2006, 40, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourment, M.; Gibbs, M.J. PATRISTIC: A Program for Calculating Patristic Distances and Graphically Comparing the Components of Genetic Change. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, D. Reproduction in Gammarus (Crustacea, Amphipoda): Basic Processes. Freshw. Forum 1992, 2, 102–128. [Google Scholar]

- Drozdova, P.; Saranchina, A.; Madyarova, E.; Gurkov, A.; Timofeyev, M. Experimental Crossing Confirms Reproductive Isolation between Cryptic Species within Eulimnogammarus verrucosus (Crustacea: Amphipoda) from Lake Baikal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristescu, M.E.; Adamowicz, S.J.; Vaillant, J.J.; Haffner, D.G. Ancient Lakes Revisited: From the Ecology to the Genetics of Speciation. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 4837–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenuil, A.; Saucède, T.; Hemery, L.G.; Eléaume, M.; Féral, J.-P.; Améziane, N.; David, B.; Lecointre, G.; Havermans, C. Understanding Processes at the Origin of Species Flocks with a Focus on the Marine Antarctic Fauna. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, B.W.; Forsman, Z.H.; Whitney, J.L.; Faucci, A.; Hoban, M.; Canfield, S.J.; Johnston, E.C.; Coleman, R.R.; Copus, J.M.; Vicente, J.; et al. Species Radiations in the Sea: What the Flock? J. Hered. 2020, 111, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copilaș-Ciocianu, D.; Sidorov, D. Taxonomic, Ecological and Morphological Diversity of Ponto-Caspian Gammaroidean Amphipods: A Review. Org. Divers. Evol. 2022, 22, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdova, P.B.; Madyarova, E.V.; Gurkov, A.N.; Saranchina, A.E.; Romanova, E.V.; Petunina, J.V.; Peretolchina, T.E.; Sherbakov, D.Y.; Timofeyev, M.A. Lake Baikal Amphipods and Their Genomes, Great and Small. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2024, 28, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhteev, V.V. On the current state of taxonomy of the Baikal Lake amphipods (Crustacea, Amphipoda) and the typological ways of constructing their system. Arthropoda Sel. 2019, 28, 374–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneliya, M.E.; Väinölä, R. Five Subspecies of the Dorogostaiskia parasitica Complex (Dybowsky) (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Acanthogammaridae), Epibionts of Sponges in Lake Baikal. Hydrobiologia 2014, 739, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkov, A.; Rivarola-Duarte, L.; Bedulina, D.; Fernández Casas, I.; Michael, H.; Drozdova, P.; Nazarova, A.; Govorukhina, E.; Timofeyev, M.; Stadler, P.F.; et al. Indication of Ongoing Amphipod Speciation in Lake Baikal by Genetic Structures within Endemic Species. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijering, M.P.D. Physiologische Beiträge Zur Frage Der Systematischen Stellung von Gammarus pulex (L.) Und Gammarus fossarum Koch (Amphipoda). Crustaceana 1972, 313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kolding, S. Interspecific Competition for Mates and Habitat Selection in Five Species of Gammarus (Amphipoda: Crustacea). Mar. Biol. 1986, 91, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.L.; Hogg, I.D.; Waas, J.R. Phylogeography and Species Discrimination in the Paracalliope fluviatilis Species Complex (Crustacea: Amphipoda): Can Morphologically Similar Heterospecifics Identify Compatible Mates? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 99, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cothran, R.D.; Stiff, A.R.; Chapman, K.; Wellborn, G.A.; Relyea, R.A. Reproductive Interference via Interspecific Pairing in an Amphipod Species Complex. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2013, 67, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrue, C.; Wattier, R.; Galipaud, M.; Gauthey, Z.; Rullmann, J.-P.; Dubreuil, C.; Rigaud, T.; Bollache, L. Confrontation of Cryptic Diversity and Mate Discrimination within Gammarus pulex and Gammarus fossarum Species Complexes. Freshw. Biol. 2014, 59, 2555–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipaud, M.; Gauthey, Z.; Turlin, J.; Bollache, L.; Lagrue, C. Mate Choice and Male–Male Competition among Morphologically Cryptic but Genetically Divergent Amphipod Lineages. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2015, 69, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupało, K.; Copilaș-Ciocianu, D.; Leese, F.; Weiss, M. Morphology, Nuclear SNPs and Mate Selection Reveal That COI Barcoding Overestimates Species Diversity in a Mediterranean Freshwater Amphipod by an Order of Magnitude. Cladistics 2023, 39, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdova, P.; Shatilina, Z.; Mutin, A.; Saranchina, A.; Gurkov, A.; Timofeyev, M. The Curious Case of Eulimnogammarus cyaneus (Dybowsky, 1874): Reproductive Biology of a Widespread Endemic Littoral Amphipod from Lake Baikal. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 2025, 343, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashiko, K.; Kamaltynov, R.; Morino, H.; Sherbakov, D.Y. Genetic Differentiation among Gammarid (Eulimnogammarus cyaneus) Populations in Lake Baikal, East Siberia. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2000, 148, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väinölä, R.; Kontula, T.; Mashiko, K.; Kamaltynov, R.M. Congruent and Hierarchical Intra-Lake Subdivisions from Nuclear and Mitochondrial Data of a Lake Baikal Shoreline Amphipod. Diversity 2024, 16, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranchina, A.; Mutin, A.; Govorukhina, E.; Rzhechitskiy, Y.; Gurkov, A.; Timofeyev, M.; Drozdova, P. Genetic Diversity in a Baikal Species Complex Eulimnogammarus verrucosus (Amphipoda: Gammaroidea) in the Angara River, the Only Outflow of Lake Baikal. Zool. Scr. 2024, 53, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazikalova, A.Y. Amphipods of Lake Baikal; Proceedings of the Baikal Limnological Station; Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences: Moscow, Russia; Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Govorukhina, E.B. Biology of Reproduction, Seasonal and Daily Dynamics of Littoral and Sublittoral Amphipod Species of Lake Baikal. Ph.D. Thesis, Irkutsk State University, Irkutsk, Russia, 2005. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Bazikalova, A.Y. On the Growth of Some Amphipods from Baikal and Angara. Proc. Baikal Limnol. Stn. 1951, 13, 206–216. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lipaeva, P.; Drozdova, P.; Vereshchagina, K.; Jakob, L.; Schubert, K.; Bedulina, D.; Luckenbach, T. How to Reproduce in the Siberian Winter: Proteome Dynamics Reveals the Timing of Reproduction-Related Processes in an Amphipod Species Endemic to Lake Baikal. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipaeva, P.; Vereshchagina, K.; Drozdova, P.; Jakob, L.; Kondrateva, E.; Lucassen, M.; Bedulina, D.; Timofeyev, M.; Stadler, P.; Luckenbach, T. Different Ways to Play It Cool: Transcriptomic Analysis Sheds Light on Different Activity Patterns of Three Amphipod Species under Long-Term Cold Exposure. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 5735–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedotov, A.P.; Khanaev, I.V. Annual Temperature Regime of the Shallow Zone of Lake Baikal Inferred from High-Resolution Data from Temperature Loggers. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 4, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.V.; Hampton, S.E.; Izmest’eva, L.R.; Silow, E.A.; Peshkova, E.V.; Pavlov, B.K. Climate Change and the World’s “Sacred Sea”—Lake Baikal, Siberia. BioScience 2009, 59, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeyev, M.; Shatilina, J.; Stom, D. Attitude to Temperature Factor of Some Endemic Amphipods from Lake Baikal and Holarctic Gammarus lacustris Sars, 1863: A Comparative Experimental Study. Arthropoda Sel. 2001, 10, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalle, R.; Gregory, T.R.; Johnston, J.S. Preparation of Samples for Comparative Studies of Arthropod Chromosomes: Visualization, in situ Hybridization, and Genome Size Estimation. In Molecular Evolution: Producing the Biochemical Data; Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 395, pp. 460–488. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, W.E.; Price, A.L.; Gerberding, M.; Patel, N.H. Stages of Embryonic Development in the Amphipod Crustacean, Parhyale Hawaiensis. Genesis 2005, 42, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, J.; Piro, K.; Weigand, A.; Plath, M. Small-Scale Phenotypic Differentiation along Complex Stream Gradients in a Non-Native Amphipod. Front. Zool. 2019, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, Y.A.; Saranchina, A.E.; Shatilina, Z.M.; Kashchuk, N.D.; Timofeyev, M.A. Comparison of Olfactory Sensilla Structure in Littoral and Deep-Water Amphipods from the Baikal Region. Inland Water Biol. 2023, 16, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englisch, U.; Coleman, C.O.; Wägele, J.W. First Observations on the Phylogeny of the Families Gammaridae, Crangonyctidae, Melitidae, Niphargidae, Megaluropidae and Oedicerotidae (Amphipoda, Crustacea), Using Small Subunit rDNA Gene Sequences. J. Nat. Hist. 2003, 37, 2461–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, Y.I.; Belov, D.A.; Alekseev, Y.V. Multichannel Capilary Genetic Analyzer. Russian Patent RU 2693583 C1, 2 July 2019. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Bocharova, D.V.; Alekseev, Y.I.; Volkov, A.A.; Lavrov, G.S.; Plugov, A.G.; Volkov, I.A.; Chemigov, A.A.; Bardin, B.V.; Kurochkin, V.E. Determination of the Maximum Length of DNA in a Polymer Based on Linear Poly(N,N-Dimethylacrylamide) Decoded with an Accuracy of 99% by Capillary Gel Electrophoresis with Laser-Induced Fluorescence. J. Anal. Chem. 2021, 76, 1408–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald III, K.S.; Yampolsky, L.; Duffy, J.E. Molecular and Morphological Evolution of the Amphipod Radiation of Lake Baikal. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2005, 35, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M. Unipro UGENE: A Unified Bioinformatics Toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivarola-Duarte, L.; Otto, C.; Jühling, F.; Schreiber, S.; Bedulina, D.; Jakob, L.; Gurkov, A.; Axenov-Gribanov, D.; Sahyoun, A.H.; Lucassen, M.; et al. A First Glimpse at the Genome of the Baikalian Amphipod Eulimnogammarus verrucosus. J. Exp. Zool. Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2014, 322, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Cahill, V.; Ballment, E.; Benzie, J. The Complete Sequence of the Mitochondrial Genome of the Crustacean Penaeus Monodon: Are Malacostracan Crustaceans More Closely Related to Insects than to Branchiopods? Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D.; Posit Software, PBC. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, E.; Sherrill-Mix, S.; Dawson, C. Ggbeeswarm: Categorical Scatter (Violin Point) Plots. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggbeeswarm (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Use R! Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A. Ggpubr: “ggplot2” Based Publication Ready Plots. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Slowikowski, K.; Schep, A.; Hughes, S.; Dang, T.K.; Lukauskas, S.; Irisson, J.-O.; Kamvar, Z.N.; Ryan, T.; Christophe, D.; Hiroaki, Y.; et al. Ggrepel: Automatically Position Non-Overlapping Text Labels with “Ggplot2”. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggrepel (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Giraud, T. Maptiles: Download and Display Map Tiles. Available online: https://github.com/riatelab/maptiles (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Novomestky, F. Matrixcalc: Collection of Functions for Matrix Calculations. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=matrixcalc (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Schauberger, P.; Walker, A.; Braglia, L.; Sturm, J.; Garbuszus, J.M.; Barbone, J.M.; Zimmermann, D.; Kainhofer, R. Openxlsx: Read, Write and Edit Xlsx Files. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=openxlsx (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wickham, H. Reshaping Data with the Reshape Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, D.; Wickham, H. Ggmap: Spatial Visualization with Ggplot2. R J. 2013, 5, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Pedersen, T.L.; Seidel, D. Scales: Scale Functions for Visualization. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scales (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R. Spatial Data Science: With Applications in R, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-0-429-45901-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hernangómez, D. Using the Tidyverse with Terra Objects: The Tidyterra Package. J. Open Source Softw. 2023, 8, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudis, B.; Gandy, D. Waffle: Create Waffle Chart Visualizations. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=waffle (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Arzhannikov, S.G.; Ivanov, A.V.; Arzhannikova, A.V.; Demonterova, E.I.; Jansen, J.D.; Preusser, F.; Kamenetsky, V.S.; Kamenetsky, M.B. Catastrophic events in the Quaternary outflow history of Lake Baikal. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 177, 76–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueckert, S.; Simdyanov, T.G.; Aleoshin, V.V.; Leander, B.S. Identification of a Divergent Environmental DNA Sequence Clade Using the Phylogeny of Gregarine Parasites (Apicomplexa) from Crustacean Hosts. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedulina, D.S.; Evgen’ev, M.B.; Timofeyev, M.A.; Protopopova, M.V.; Garbuz, D.G.; Pavlichenko, V.V.; Luckenbach, T.; Shatilina, Z.M.; Axenov-Gribanov, D.V.; Gurkov, A.N.; et al. Expression Patterns and Organization of the Hsp70 Genes Correlate with Thermotolerance in Two Congener Endemic Amphipod Species (Eulimnogammarus cyaneus and E. verrucosus) from Lake Baikal. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 1416–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoseeva, E.V.; Stom, D.I. Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide on Behavioural Reactions and Survival of Various Lake Baikal Amphipods and Holarctic Gammarus Lacustris G. O. Sars, 1863. Crustaceana 2013, 86, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madyarova, E.V.; Adelshin, R.V.; Dimova, M.D.; Axenov-Gribanov, D.V.; Lubyaga, Y.A.; Timofeyev, M.A. Microsporidian Parasites Found in the Hemolymph of Four Baikalian Endemic Amphipods. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, L.; Axenov-Gribanov, D.V.; Gurkov, A.N.; Ginzburg, M.; Bedulina, D.S.; Timofeyev, M.A.; Luckenbach, T.; Lucassen, M.; Sartoris, F.J.; Pörtner, H.-O. Lake Baikal Amphipods under Climate Change: Thermal Constraints and Ecological Consequences. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdova, P.; Rivarola-Duarte, L.; Bedulina, D.; Axenov-Gribanov, D.; Schreiber, S.; Gurkov, A.; Shatilina, Z.; Vereshchagina, K.; Lubyaga, Y.; Madyarova, E.; et al. Comparison between Transcriptomic Responses to Short-Term Stress Exposures of a Common Holarctic and Endemic Lake Baikal Amphipods. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.L.; Hogg, I.D.; Waas, J.R. Is Size Assortative Mating in Paracalliope fluviatilis (Crustacea: Amphipoda) Explained by Male–Male Competition or Female Choice? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2007, 92, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, V.K.; Starks, B.D. Sexual Selection in Harems: Male Competition Plays a Larger Role than Female Choice in an Amphipod. Behav. Ecol. 2008, 19, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beermann, J.; Dick, J.T.A.; Thiel, M. Social Recognition in Amphipods: An Overview. In Social Recognition in Invertebrates: The Knowns and the Unknowns; Aquiloni, L., Tricarico, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 85–100. ISBN 978-3-319-17599-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chaw, R.C.; Patel, N.H. Independent Migration of Cell Populations in the Early Gastrulation of the Amphipod Crustacean Parhyale hawaiensis. Dev. Biol. 2012, 371, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Drozdova, P.; Shatilina, Z.; Telnes, E.; Gurkov, A.; Saranchina, A.; Mutin, A.; Zolotovskaya, E.; Timofeyev, M. Prezygotic and Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibilities Complement Each Other in the Formation of a Cryptic Amphipod Species: The Example of a Lake Baikal Species Complex Eulimnogammarus verrucosus. Diversity 2025, 17, 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110781

Drozdova P, Shatilina Z, Telnes E, Gurkov A, Saranchina A, Mutin A, Zolotovskaya E, Timofeyev M. Prezygotic and Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibilities Complement Each Other in the Formation of a Cryptic Amphipod Species: The Example of a Lake Baikal Species Complex Eulimnogammarus verrucosus. Diversity. 2025; 17(11):781. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110781

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrozdova, Polina, Zhanna Shatilina, Ekaterina Telnes, Anton Gurkov, Alexandra Saranchina, Andrei Mutin, Elena Zolotovskaya, and Maxim Timofeyev. 2025. "Prezygotic and Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibilities Complement Each Other in the Formation of a Cryptic Amphipod Species: The Example of a Lake Baikal Species Complex Eulimnogammarus verrucosus" Diversity 17, no. 11: 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110781

APA StyleDrozdova, P., Shatilina, Z., Telnes, E., Gurkov, A., Saranchina, A., Mutin, A., Zolotovskaya, E., & Timofeyev, M. (2025). Prezygotic and Postzygotic Reproductive Incompatibilities Complement Each Other in the Formation of a Cryptic Amphipod Species: The Example of a Lake Baikal Species Complex Eulimnogammarus verrucosus. Diversity, 17(11), 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110781