Abstract

The rodents of Saudi Arabia consist of twenty species and twelve genera within four families (Gliridae, Dipodidae, Muridae, and Hystricidae). Details on the past and present distribution of the rodents were included, along with available data on their habitat preference and biology. The eastern central part of Saudi Arabia, covering the Tuwiq mountains plateau, including the vicinity of Riyadh, hosts the highest number of rodent species. An analysis of the rodent fauna of Saudi Arabia revealed that they have four major zoogeographical affinities: Palaearctic–Oriental (one species), Afrotropical–Palaearctic (six species), Palaearctic (four species), endemic to Saudi Arabia and Yemen (three species), Afrotropical–Palaearctic–Oriental (three species), and three cosmopolitan species. According to the National Red List, the Euphrates Jerboa, Scarturus euphraticus, is listed as endangered, the Indian Crested Porcupine, Hystrix indica, as near threatened, three further species as data-deficient, while the rest are considered least concern.

1. Introduction

Rodents are considered the largest order of mammals worldwide, comprising about 50% of living mammals. They are distributed all over the world in almost all types of habitats, including forests, temperate, tropical, deserts, and riparian habitats, as well as human-inhabited areas [1,2].

Species of this order play an important role in arid regions. Some keystone species are considered ecosystem engineering, where they propagate seeds, increase plant productivity around their burrows, and provide shelter for arthropods and reptiles in their deserted burrows, as well as a food source for small and medium carnivores, snakes, and raptors [3,4].

Studies on the systematics and distribution of the rodents of Saudi Arabia have been published over the past century [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], with a total of 20 extant species. The most comprehensive study was published by Büttiker and Harrison [14]. Other studies addressed the ecology and biology of some species: the Southwest Asian Garden Dormouse, Eliomys melanurus [15], the Yemen White-footed Rat, Ochromyscus yemeni [16], and the reproductive biology of the Baluchistan gerbil, Gerbillus nanus [17].

Studies have investigated the locomotory activity rhythm of Eliomys melanurus, Acomys dimidiatus, Meriones rex, Meriones lybicus, and Gerbillus dasyurus [18,19,20,21]. Rodents remains in owl pellets have been studied by several authors, providing additional locality records [22,23,24,25].

The present study updates the taxonomy and distributional data for 20 rodent species based on previous records and the recent results of field work, addresses their zoogeographical affinities, and identifies the threats facing some rodent species in Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

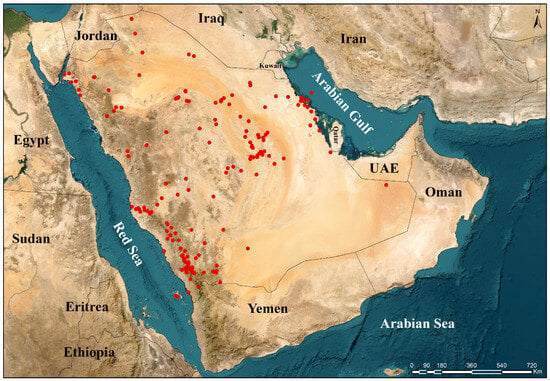

Previous records for the rodents of Saudi Arabia were extracted from published papers, reports, and the mammal’s collection of the late Prof. Iyad Nader, deposited at the National Center for Wildlife (NCW). Additionally, personal observations of rodents recovered from owl pellets and from trapping in different sites in Saudi Arabia by the NCW field biologists over the past three years (2022–2024), are included. Data on rodents’ distribution cover 176 localities (Figure 1, Appendix A). Records for each species reported previously are indicated with the reference number in parentheses. Scientific and common names were checked according to Burgin et al. [26].

Figure 1.

Map of Saudi Arabia showing localities of reported rodents.

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of the Rodent Fauna of Saudi Arabia

The rodents of Saudi Arabia consist of twenty species in four families (Gliridae, Dipodidae, Muridae, and Hystricidae) and twelve genera. The family Muridae includes sixteen species, while the families Gliridae and Hystricidae include one species each, and the family Dipodidae includes two species.

Family Gliridae

Dormice occurs mostly in Europe, with some species in Asia and Africa. Members of this family are characterized by a hairy and bushy tail and by the presence of four ckeekteeth in the maxilla. Members of this family are known to have an arboreal lifestyle, while some occur among accumulated rocks and boulders. In Saudi Arabia, this family includes a single species.

Eliomys melanurus (Wagner, 1839) (Figure 2A)

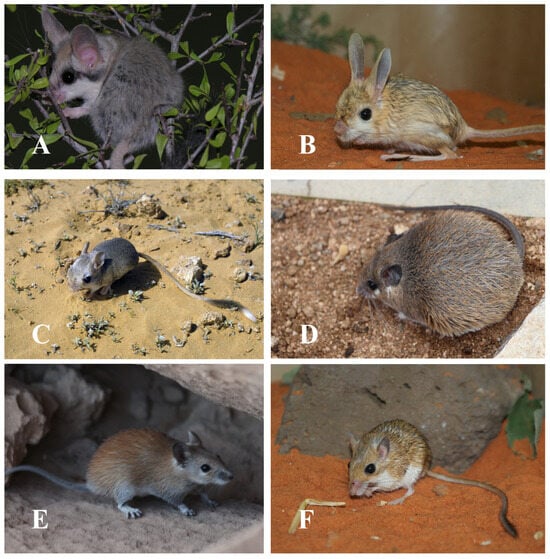

Figure 2.

(A) Eliomys melanurus. (B) Scarturus euphratica (Photo by A. Shehab). (C) Jaculus loftusi. (D) Acomys dimidiatus. (E) Acomys russatus (Photo by B. Rubinic). (F) Gerbillus dasyurus (Photo by A. Shehab).

Common name: Southwest Asian Garden Dormouse

Arabic name: فأر الحديقة الجنوب غربي الأسيوي

Global distribution: Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey.

Previous records: Dar el Harma [6], Jabal Shar, Medain Salih, Wadi Dalaghan [15,27], Raydah Protected Area [18].

Recent records: 35 km SE Abha, Alagan, Al Souda, Neom, Tabuk.

Habitat and ecology: It occurs in very arid and densely vegetated habitats. It was collected in sandstone deserts and rocky areas. It feeds on insects, snails, and centipedes. They come out at night and feed on wild fig trees. The Southwest Asian Garden Dormouse became adapted to a presumably arboreal lifestyle 1.2 million years ago [28]. This species has a remarkable distribution pattern, despite being originally an arboreal species. Populations of this species may represent relicts in the deserts of Saudi Arabia [29].

Biology: Females give birth to 2–9 young, and become fully mature by one year [30]. The Southwest Asian Garden Dormouse lives along with other desert rodents, such as Gerbillus dasyurus and Acomys russatus [31]. Alagaili et al. [18] studied the locomotor activity of this species under controlled environment in Saudi Arabia. Al Khalili [32] recovered Myoxopsylla laverania parasitizing this species.

Family Dipodidae

The elongated hind limbs and short forearms characterize members of this family. This is an adaptation for saltatorial movement. Two genera are recognized in Saudi Arabia, Scarturus and Jaculus. Both contain one species that are found in dry, arid parts of the country.

Scarturus euphraticus (Thomas, 1881) (Figure 2B)

Common name: Euphrates Jerboa

Arabic name: الجربوع الفراتي

Global distribution: Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Qaisumah [7], Summan Plateau [9], Turaif [12], Ara’r [24].

Recent records: Luga.

Habitat and ecology: This is a true desert species, restricted to the arid habitats of Saudi Arabia. It is mostly associated with wadis in dry parts of the country and avoids sand habitats. In Saudi Arabia, burrows may reach up to 45 cm deep and about one meter long with one single entrance [7].

Biology: The Euphrates Jerboa becomes active after sunset and looks for food close to its burrow site. Females may give birth to up to nine young. Kadhim and Wahid [33] examined the reproduction of S. euphraticus males and stated that the period of February to May includes a higher level of breeding activity for males, with a second activity period during October. In Saudi Arabia, many remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus and possibly the Omani owl, Strix butleri, and the Barn Owl, Tyto alba [9].

Jaculus loftusi (Blanford, 1875) (Figure 2C)

Common name: Arabian Jerboa

Arabic name: الجربوع العربي

Global distribution: Arabian Peninsula, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq (W of Euphrates).

Distribution in Saudi Arabia

Previous report: Artawiya [6], Summan Plateau [9], Harrart Al Harrah [10,34], Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth [11,35], Turaif [12], Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Al Khubra, Mekka by pass, Makkah-Lith, Wadi Sirhan [14], Ara’r [24], Al Daba’ah, Bsitah [25], Hazm an-Nuquria, Ras al-Abkhara [36], Uruq Bani Ma’arid [37].

Recent records: Al Thumamah, Buridah, Luga, Qbah, NW Riyadh, Sha’ib Al Shoki, Shaybah, Tabuk.

Habitat and ecology: The ecology of the Arabian Jerboa is well studied in Saudi Arabia [7]. It is a nocturnal species and remains active for the first 3 to 4 h after dark. Burrows are situated in leveled arid areas and may reach up to 120 cm deep with several food chambers, a nest, and several blind alleys. The entrance is plugged by sand during the daytime. Jaculus loftusi is a successful desert colonial species. In Turaif, it was a very common species in high densities [12]. It is mostly associated with open gravel plains. It inhabits a wide variety of habitats, including sabkhas, sand, and alluvial deserts covered by chenopods [14].

Biology: It is a nocturnal species and remains active for the first 3 to 4 h after dark. Females produce 2–7 newborns after a gestation period that lasts for about 25 days [7,38]. The Arabian Jerboa is one of the prey items for desert owls in Saudi Arabia [6,34]. Two flea species, Xenopsylla cheopis and Ctenocephalides felis, were also found to parasitize this species in the vicinity of Riyadh [39].

Remarks: According to Shenbrot et al. [40], the Asian population of this species should be referred to as Jaculus loftusi (Blanford, 1875). Both Jaculus hirtipes (H. Lichtenstein, 1823) and Jaculus jaculus (Linnaeus, 1758) are distributed in North Africa and the Sahara [40].

Family Muridae

A recent revision of Order Rodentia made radical changes in the systematics of this order [1,2]. By now, three main subfamilies are known to occur in Saudi Arabia (Gerbillinae, Murinae, and Deomyinae). This family includes rats, jirds, and gerbils that assume different lifestyles. It includes species that are considered serious pests of economic and health importance.

Acomys dimidiatus (Cretzschmar, 1826) (Figure 2D)

Common name: Eastern Spiny Mouse

Arabic name: الفأر الشوكي الشرقي

Global distribution: Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Yemen, Oman, Saudi Arabia, S Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Abha, Birka, Rumah, Shaib Hajlil, Wadi Liya [6], Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Adama, Adnan, Al Haniq, Al Na’amah, SW Al Ula, Al Wajh, Artawiyah, Ash Sharayi, 38 km S Athnen, Bani Musayqirah, Hamid, Hesua, Fayfa, Jabal Ammariyah, Jabal Al Alam, Jabal Farrash, Kushm Buwaybiyat, Kushm Dibi, Shaib al Tawqi, Tala’a, Thamniya, Wadi Karrar, Wadi Khumra, Wadi Qatan, Wadi Rasid, Wadi Sanakhah, Wadi Shaib Luha, Wadi Thalham, Wadi Turabah, Wadi Wajj [14], Riydaha Protected Area [19], Al Daba’ah [25], Riyadh [39], Wadi Sharayi [41], Wadi Hanifah [42], Farasan Al-Kebir [43], Aga, Alzobara, Barazan, Eljameayein, Elkhomashiya [44], Alogl, Alous, Wosanib [45], Riyadh Province [46].

Recent records: Dirab, Duba, Harrat Kishb, Ibex Reserve, Jeddah, Neom, NW Riyadh, Tabuk, Wadi Dalagan.

Habitat and ecology: The Eastern Spiny Mouse is a rock-dwelling species, including mesic and xeric biotopes. It is found across the entire mountain range, extending along Hijaz and reaching southwards to the Abha mountains [14]. It can be found in rocky areas with trees and shrubs. It also invaded forest habitats in south-western Saudi Arabia. In Hisma, around Tabuk, it is associated with dry sandstone mountains with minimal vegetation.

Biology: It is strictly nocturnal, in contrast to the Golden Spiny Mouse, Acomys russatus. In arid regions, the Eastern Spiny Mouse feeds on land snails and seeds of various plants. The entrance of its burrow is usually piled with crushed land snails of several genera [29]. Also, the entrance may be plugged by thorny plants, perhaps to prevent intruders (e.g., snakes) from entering. Gestation lasts for 36–40 days, and the young (two or three, at most five) are born mainly in the spring and summer months [2]. The circadian rhythm of locomotory activity of this species was studied under controlled conditions [19]. Al Khalili [32] recovered parasites from this species, including Parapulex chephrenis, Xenopsylla cheopis, Stenoponia tripectinata, Rhipcephalus sanguineus, and Haemaphysalis sulcata. Al-Ahmed and Al-Dawood [42] collected Xenopsyllus sp., and Rhipicephalus turanicus parasitizing this species in the vicinity of Riyadh. Two flea species, Xenopsylla cheopis and Ctenocephalides felis, were also found to parasitize this species [39]. Stekolnikov et al. [45] collected several species of chigger mites parasitizing on this species.

Remarks: Morphologically, A. dimidiatus is very similar to Acomys cahirinus. Molecular studies showed several major groups in Africa and Arabia [46]. They referred to the Arabian and Sinai populations as A. dimidiatus, while Acomys cahirinus is distributed in Egypt, Crete, Cyprus, Turkey, Libya, and northern Chad. On the other hand, Bray et al. [47] found a second Acomys dimidiatus/cahirinus lineage specific to the Arabian Peninsula. Thus, more studies on the taxonomic status of this species are urgently required to validate its taxonomy.

Acomys russatus (Wagner, 1840) (Figure 2E)

Common name: Golden Spiny Mouse

Arabic name: الفأرالشوكي الذهبي

Global distribution: E Egypt, Sinai, Jordan, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Wadi Liya [6], Tuwaiq Escarpment, Wadi Khumra [14], Wadi As Sulai [22], Riyadh Province [48].

Recent records: Jabal Al Aswad, Harrat Kishb, Harrat Khaybar, NW Riyadh. Ibex Reserve

Habitat and ecology: This species is common in rocky areas around the Arabian Sheild and the western mountains. Atallah [31] stated that the Golden Spiny Mouse lives along with A. dimidiatus; both species prefer rocky terrain. It feeds on several halophytic plants, such as Anabasis articulata, Atriplex halimus, and Hammada scorpia [49].

Biology: The Golden Spiny Mouse is nocturnal in areas where A. dimidiatus is absent, while it is active in the morning hours and late afternoon in habitats shared with A. dimidiatus [50].

Remarks: It is highly possible to find the melanistic form Acomys russatus lewisi in the black lava deserts of Harrat Al Harrah [29].

Subfamily Gerbillinae

This subfamily includes gerbils and jirds. This subfamily constitutes the largest group of rodents occurring in Saudi Arabia, with four genera, Gerbillus, Meriones, Psammomys, and Sekeetamys, with a total of ten species.

Gerbillus dasyurus (Wagner, 1842) (Figure 2F)

Common name: Wagner’s Gerbil

Arabic name: عضل واجنر

Global distribution: Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Sinai.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Artawiya, Balum wells, Thamami wells [6], Summan Plateau [9], Harrat Al Harrah [10], Wadi As Sulai [13], Al Haniq, Al Wajh, An Namas, An Na’amah, Jabal Banban, Jabal Thamamah, Nuayriyah, Risayah, Thamniyah, Tumeir, Wadi Rasid [14], Ara’r [24], Al Daba’ah [25], Ras al Abkhara [36].

Recent records: Luga, Neom, Qbah, Sharma, Tabuk, Tanomah.

Habitat and ecology: Wagner’s Gerbil has a wide range of habitats, including basalt deserts, silt dunes, run-off wadis, and cultivated areas. This gerbil is very common in the Saudi Arabian deserts. It was also collected from several localities along the western mountains, the Arabian shield area, as well as open deserts. It was found to share burrows with Psammomys obesus [51].

Biology: The burrows are simple but deep, with 1–2 unplugged emergency exit. Stored plants found include Anabasis articulata, Atriplex halimus, and Artemisia herpa-alba [52]. Reproduction occurs almost all year-round and pauses in December. Gestation lasts for 18–22 days, with a litter size of 3–7 newborns [53]. In Saudi Arabia, many remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, and possibly the Omani owl, Strix butleri, and the Barn Owl, Tyto alba [9,22]. Al Khalili [31] recovered ectoparasites from this species, including Parapulex chephrenis, Xenopsylla cheopis, Xenopsylla dipodilli, Xenopsylla brasiliensis, Stenoponia tripectinata, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, and Haemaphysalis sulcata.

Gerbillus cheesmani Thomas, 1919 (Figure 3A)

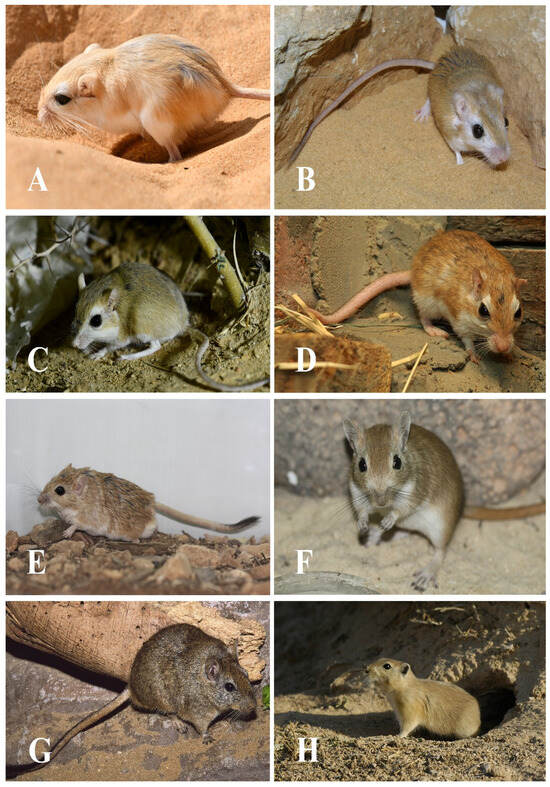

Figure 3.

(A) Gerbillus cheesmani. (B) Gerbillus henleyi (Photo by M. Abu Baker). (C) Gerbillus nanus. (D) Gerbillus poecilops (Photo by M. Jordan). (E) Meriones crassus. (F) Meriones libycus. (G) Meriones rex (Photo by R. Wirth). (H) Psammomys obesus (Photo by S. Al Jbour).

Common name: Cheesman’s Gerbil

Arabic name: عضل تشيزمان

Global distribution: SW Iran, C and S Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen and Kuwait.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Al Saiyarat, Hafr Al Batin [6], Harrat Al Harrah [10], Saja Umm Ar-Rimth [11,35], Turaif [12], Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Ash Sharayi, Al Wajh, Al Uquar, Jeddah, Makkah by pass, Salim [14], Abu Ali Island, Abu Hadriya, Dauhat ad Dafi, Hazm al Faidah, Jubail, Ras az Zaur [36], Mahazat as-Sayd [54].

Recent records: Hafir Kishb, Ibex Reserve, Immam Turki Ben Abdullah Reserve, Luga, Qubat Al Zbair, Shaybah, Urouq Bani Moa’red.

Habitat and ecology: This is a sand-dwelling species and is most abundant in red sandy areas around Ephedra alata and Calligonum shrubs. It does not form extensive burrow systems, and the burrow has one hole located under shrubs [6].

Biology: The reproduction pattern of this species was studied in Saudi Arabia by Henry and Dubost [35]. They stated that males and females reproduced synchronously, and the reproduction season coincided with rainfall. In Saudi Arabia, many remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, and possibly the Omani owl, Strix butleri, and the Barn Owl, Tyto alba [9,22].

Gerbillus henleyi (De Winton, 1903) (Figure 3B)

Common name: Pygmy Gerbil

Arabic name: العضل القزم

Global distribution: Algeria through N Africa to Palestine and Jordan, Western Saudi Arabia, N Yemen, and Oman.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Summan Plateau [9], Al Arf [14].

Habitat and ecology: The Pygmy Gerbil was collected in extreme desert habitats. It prefers gravelly as well as sandy deserts with very scarce vegetation of perennial bushes and shrubs [14]. Its burrow is characterized by its small diameter (1–2 cm).

Biology: The Pygmy Gerbil is the smallest rodent known to inhabit the Saudi Arabian deserts. A female was found to have six embryos [55]. In the Negev, two distinct breeding periods were observed, one in the spring and the second in late summer. In comparison with other species of the genus Gerbillus, G. henleyi is more of a seed eater, more mobile, and has a less stable home range than D. dasyurus. This suggests that G. henleyi is more adapted to xeric habitats than other gerbils [56]. It was collected from areas with scarce vegetation cover. In Saudi Arabia, many remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo. Ascalaphus, and possibly the Omani owl, Strix butleri, and the Barn Owl, Tyto. alba [9].

Gerbillus nanus Blanford, 1875 (Figure 3C)

Common name: Baluchistan Gerbil

Arabic name: عضل بلوشستان

Global distribution: An extensive range from the Baluchistan region of NW India, Pakistan, S Afghanistan, and Iran through the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, Jordan, and Palestine.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Artawiya, Balum wells, Median Salih, Raudha Tinhat, Rumaihiya, Thamami wells [6], Harrat Al Harrah [10], Saja Umm Ar-Rimth [11,35], Turaif [12], Wadi As Sulai [13], Ashayrah, Ath-thamamah, Al Uquar, Ar Rayn, Bahara, Dirab, Hofuf, Jabal Alam, Jabal Banban, Jabal Maniq, Jizan, Kushm Dibi, Makkah by pass, Quwaywiyah, Sanam, Todiah, Umm Ad Dabah, Wadi Awsat, Wadi Hureimala, Wadi Karj, Wadi Khumra, Wadi Nissah, Wadi Shija, Wadi Shuqub, 10 km W Al Qasab [14], Farasan Island [23], Ara’r [24], Al Aba Oasis, Dauhat al Musallamiya, Jubail, Ras al Abkhara [36], Riyadh Province [43].

Recent records: Al Qidiyah, Hail, Harrat Kishb, Harrat Khaybar, Ibex Reserve, Immam Turki Ben Abdullah Reserve, Qbah, Tabuk.

Habitat and ecology: The Dwarf Gerbil was collected from low sandy wadis with a considerable salty nature in eastern Saudi Arabia. It was found coexisting with either one of the large-sized jirds, Meriones crassus or Meriones libycus [57]. It was one of the most common species in the Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth Protected Area and was trapped along with M. crassus, M. libycus, Gerbillus cheesmani, and Jaculus loftusi [11]. Activity at its maximum is two hours after dusk [7].

Biology: This is a herbivorous species that also feeds on the seeds and buds of species of grasses. temperature. The first pregnancies were observed in late spring [17]. Litter size ranges from 2–5.

Remarks: Molecular studies showed that the Arabian G. nanus is similar to the Middle Eastern populations but different from its African conspecifics [26]. The African populations, formerly classified as G. nanus, are now considered Gerbillus amoenus (de Winton, 1902) [58].

Gerbillus poecilops Yerbury and Thomas, 1895 (Figure 3D)

Common name: Large Aden Gerbil

Arabic name: العضل العدني الكبير

Global distribution: Yemen and southwestern Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Mecca bypass, Wadi Uranah [31], Al Hadda [59].

Habitat and ecology: Very little is known about the ecology of this species in Saudi Arabia. It was trapped in cultivated fields and was found along coastal mountains in the Red Sea as well as in sandy deserts within the vicinity of inhabited areas. It was found in farms cultivated with cotton and sorghum, as well as in buildings within farms in Yemen [27].

Biology: The Large Aden Gerbil feeds on various vegetable matter [2]. Very little is known on the breeding biology of this species, it may breed in spring and summer.

Meriones crassus Sundevall, 1842 (Figure 3E)

Common name: Sundevall’s Jird

Arabic name: جرذ سندفال

Global distribution: Across North Africa from Morocco through Niger, Sudan, and Egypt to Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Ajibba, Balum wells, Gariya, Hafar Al Batin, Qunfidah, Rumaihiya [6], Summan Plateau [9], Harrat Al Harrah [10], Saja Umm Ar-Rimth [11,35], Turaif [12], Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Al Qasab, Dammam-Dhahran Rd., Hofuf, Jeddah, Nabhaniyah, Tumeir, Wadi Khumra, Wadi Shija [14], Ara’r [24], Al Daba’ah, Bsitah [25], Dauhat ad Dafi, Dauhat al Musallamiya, Hazim an Naquriya, Jubail, Ras al Abkhara [36].

Recent records: al Beda’a, Immam Turki Ben Abdullah Reserve, Luga, Maqna, Neom, Sharma, Tabuk.

Habitat and ecology: This is one of the most common jirds inhabiting the dry and arid habitats of Saudi Arabia. Büttiker and Harrison [14] indicated that sabkhas and alluvial wadi beds with relatively rich vegetation are favorite habitats for this species. This is a colonial species with extensive burrow systems. Abu Dieyeh [60] described the burrow system of Sundevall’s Jird in Jordan. The burrow has elaborate tunnels that may reach several meters, with several food and nesting chambers. Burrows are located among silty flat areas with ample vegetation around, such as Rhanterium epapposum [6].

Biology: The species feeds on a variety of food items, including desert plants, seeds (Medicago sp.), animal dung, and insects such as locusts [61]. This is a diurnal species, but it may also forage at night. In Saudi Arabia, many remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, and possibly the Omani owl, Strix. Butleri, and the Barn Owl, Tyto. alba [9,22]. Breeding occurs during the cooler months, but this species may breed all year round, producing up to three litters a year. Litter size is around three to seven young [62].

Meriones libycus Lichtenstein, 1823 (Figure 3F)

Common name: Libyan Jird

Arabic name: الجرذ الليبي

Global distribution: North Africa to Egypt, through Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Afghanistan, and into S Turkestan to W China.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Adwa, Anaiza, Artawiya, Hafr Al Batin, Rumaihiya [6], Summan Plateau [9], Harrat Al Harrah [10], Saja Umm Ar-Rimth [11], Turaif [12], Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Al Khardj, Hofuf, Thamamah, Wadi Khumra [14], Ara’r [24], Abu Hadriya, Dauhat al Musallamiya, Jubail, Ras al Abkhara [36], Riyadh Province [48].

Recent records: Hail, Immam Turki Ben Abdullah Reserve, Luga, Taif.

Habitat and ecology: The Libyan Jird is a common colonial species in north-central and north-eastern Saudi Arabia. Burrows are constructed in sand–silty hillsides near bushes around wadi beds. It forms extensive burrow systems that consist of many openings, a nest, and food chambers [26]. Atallah [63] reported that it feeds on Citrullus coloycnthis, while Vesey-Fitzgerald [6] stated that it excavates and feeds on Iris bulbs. This is a nocturnal species; however, it may also appear during the daytime.

Biology: In Saudi Arabia, remains of this species were found in pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, and possibly the Omani owl, Strix butleri, and the Barn Owl, Tyto alba [9,22,24]. Females give birth to 2–4 young [64]. Newborns were observed in March.

Remarks: listed as Meriones erthrourus Gray by Vesey-Fitzgerald [6].

Meriones rex Yerbury and Thomas, 1895 (Figure 3G)

Common name: King Jird

Arabic name: الجرذ الملك

Global distribution: Yemen and southwestern Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Hijla [6], Al Dalhan, Wadi Turabah [14], Raydah Protected Area [20], Al Baha, Taif, Wadi Dalaghan [24], Ash Sharayi, Dailami, Shaib Hanjur [65], Alogl, Wosanib [66], Abha, Kamis Mushayat, Sarhan, Wadi Bin Hashbal [67], Najran [68], Wadi Bin Hashbal, Wadi Dalaghan [69], Taif [70].

Recent records: Abha, Al Azizah, Wadi Eia.

Habitat and ecology: This is an endemic species confined to Yemen and south-western Saudi Arabia. It was found in large burrows under trees in areas on the border between desert and agricultural land [24]. It shares burrows with Acomys dimidiatus and Gerbillus spp. It seems to be very common in cultivated and uncultivated areas and forms large colonies [6]. Specimens were taken from elevations ranging from 1350 to 2200 m a.s.l. [14].

Biology: The King Jird is active during the evening and early morning hours, where it was observed feeding on shoots. It feeds on Salvadora persica. The locomotory activity patterns of the King Jird were studied under controlled conditions [20]. Several studies investigated the ectoparasites associated with this species; Al Khalili [32] recovered Xenopsylla brasiliensis, Stenoponia tripectinata, Rhipicephalus sangeinius, and Haemaphysalis sp., while Al Mohammed [69] found Xenopsylla astia, Ctenocephalides arabicus, and Ornithonyssus bacoti and Androlaelaps tateronis, Parapulex chephrensis, Synosternus cleopatrae, Xenopsylla conformis mycerini, Xenopsylla nubica, Hyalomma impeltatum, and Rhipicephalus camicasi were collected by Harrison et al. [70].

Psammomys obesus Cretzschmar, 1828 (Figure 3H)

Common name: Fat Sand Rat

Arabic name: جرذ الرمل السمين

Global distribution: In North Africa, from Algeria through Tunisia and coastal region of Egypt into Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and parts of Arabia, also on the coast of Sudan.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Hail, Median Saleh [6], Wadi As Sulai [22], Abqaiq, Nabek [24], Riyadh Province [48], Dailami [55], Safaha Desert, near Hail [65], Tabuk [71].

Habitat and ecology: The Sand Fat Jird is a colonial species forming large colonies constructed close to Anabasis sp. shrubs. The ecology of this species was studied by Amr and Saliba [51], who reported on its diurnal activity, feeding habits, burrow system, and association with other animals. In Saudi Arabia, it is found in gravelly deserts. It avoids rocky areas.

Biology: This is a strictly diurnal species that can be observed near the burrow opening. The gestation period may last for 23–25 days, and females give birth to 2–8 young [64].

Remarks: The Saudi subspecies Psammomys obesus dianae was described by Dailami [55].

Sekeetamys calurus (Thomas, 1892) (Figure 4A)

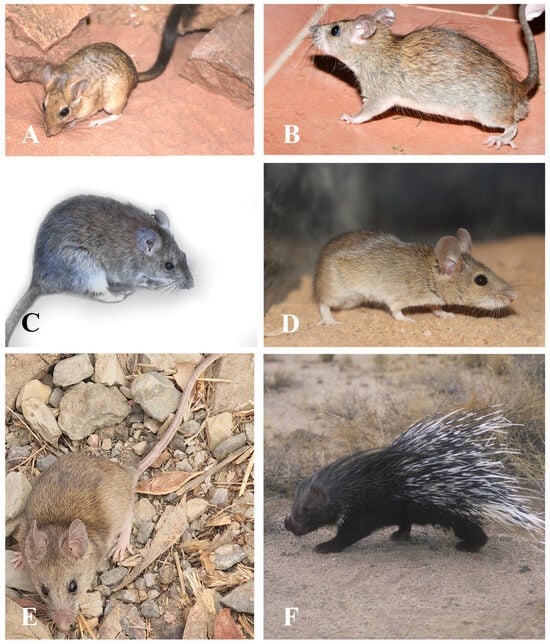

Figure 4.

(A) Sekeetamys calurus (Photo by M. Abu Baker). (B) Rattus rattus. (C) Rattus norvegicus. (D) Mus musculus. (E) Ochromyscus yemeni (Photo by C. Bocos). (F) Hystrix indica.

Common name: Bushy-tailed Jird

Arabic name: الجرذ كثيف الذيل

Global distribution: From E Egypt through Sinai, S Palestine, and Jordan into Central Saudi Arabia and Oman.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Jabal Banban, Wadi Khumra [14], Wadi As Sulai [22], Tuwaiq Mountains 36 km SW Riyadh [72].

Recent records: Hail, Neom, Majama’ Al Hadab.

Habitat and ecology: This species prefers to live around mountain slopes in arid regions. It is a good climber, and perhaps it lives under boulders. Specimens were collected from a rocky ledge on the eastern side of the Tuwaiq mountains and were found to be associated with Acomys dimidiatus and Gerbillus nanus [72].

Biology: The Bushy-tailed Jird is a nocturnal species; there is very little knowledge on its biology. Specimens from Saudi Arabia were pregnant in February with three embryos [72]. In Palestine, it was found to be in breeding condition in February and March [61]. In captivity, a female gave birth to four offspring [68]. Vegetation observed near its burrows includes the Wild Fig, Ficus pseudo-sycomorus. Osborn and Helmy [64] included many desert plants as part of their diet (Zilla spinosa, Citrullus colocynthis, etc.). It subsists on dry vegetation, seeds, and arthropods [73]. Remains of this jird were found in Vulpes cana fecal remains [74]. In Saudi Arabia, remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl [22].

Remarks: The dark morph, Sekeetamys makrami (Setzer, 1961), was described from the eastern desert of Egypt; however, subsequent publications consider it a subspecies of S. calurus [64].

Subfamily Murinae

Species of this subfamily are characterized by relatively long tails covered by scales. The tail does not terminate with a hair tuft. Four species have been confirmed to occur in Saudi Arabia, including three genera, Rattus, Mus, and Ochromyscus, while Nesokia indica was not listed until further investigation since it was reported more than 50 years ago with no additional records [27].

Rattus rattus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Figure 4B)

Common name: Black Rat

Arabic name: الجرذ الأسود

Global distribution: All over the world.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Dammam Port, Hofuf, Jeddah, Riyadh [14], Al Aba Oasis [36], Wadi Hanifah [41], Aga, Alzobara, Barazan, Eljameayein, Elkhomashiya [43], Alous [66].

Recent records: Bani Malik, Farasan Island, Jabal Al Lith Island.

Habitat and ecology: This is a common species occurring in cities, villages, and farming areas. Its populations are increasing rapidly in association with urban and agricultural expansion. The Black Rat successfully invaded remote areas in the country. This was facilitated by vehicles transporting animal food and other agricultural crops.

Biology: Breeding takes place between March and November; three to five litters can be produced in a year, each litter containing one to sixteen young. In Saudi Arabia, remains were found in pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus [22]. Al-Ahmed and Al-Dawood [41] collected Xenopsylla sp., and Rhipicephalus turanicus, while El Bahrawy and Al Dakhil [39] recovered two fleas, Xenopsylla cheopis and Ctenocephalides felis, and one louse, Polyplax spinulosa, parasitizing this species in the vicinity of Riyadh. At Al lith Island, it was found to feed on the eggs of the vulnerable Sooty Falcons, Falco concolor, causing a considerable decline in its population growth.

Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) (Figure 4C)

Common name: Brown Rat

Arabic name: الجرذ البني

Global distribution: All over the world.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Dammam, Hofuf, Jeddah [14], Riyadh [39], Aga, Alzobara, Barazan, Eljameayein, Elkhomashiya [43].

Recent records: Taif, Al Khobar, Jazan port area.

Habitat and ecology: This rat inhabits urban areas, especially seaports, as well as farmlands or where there is fresh water (canals, sewers, etc.), preferably with muddy banks, where it is possible to build dens. It is not as common as the Black Rat. From the Hail region, it seems common in farms and around human habitation [43].

Biology: El Bahrawy and Al Dakhil [39] recovered two fleas, Xenopsylla cheopis and Ctenocephalides felis, and one louse, Polyplax spinulosa, parasitizing this species in the vicinity of Riyadh.

Mus musculus Linnaeus, 1758 (Figure 4D)

Common name: House Mouse

Arabic name: فأر المنزل

Global distribution: Spread over the world’s continents and islands (except Antarctica) through its close association with humans.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Harrat Al Harrah [10], Wadi As Sulai [13,22], Al Khardj, Al Khubra, Bani Sar, Buridah, Dammam, Hofuf, Jeddah, Riyadh, Wadi Turabah, [14], Bsitah [25], Abu Ali Island, Al Aba Oasis, Hazm an Nuquriya, Karan Island, Jana Island, Jubail, Ras al Abkhara [36], Alogl [66].

Recent records: Jazan.

Habitat and ecology: The House Mouse is a very successful species that is found in all types of habitats, including deserts. The House Mouse is commonly found in modern and old houses, shops, hotels, and farms.

Biology: They breed about 12 times per year, giving birth to about 5–8 newborns each time. Within six weeks, the young are able to reproduce. In Saudi Arabia, remains were found in the pellets of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus [22]. El Bahrawy and Al Dakhil [39] recovered two fleas, Xenopsylla cheopis and Ctenocephalides felis, and one louse, Polyplax spinulosa, parasitizing this species in the vicinity of Riyadh.

Ochromyscus yemeni(Sanborn and Hoogstraal, 1953) (Figure 4E)

Common name: Yemen White-footed Rat

Arabic name: جرذ اليمن ابيض الارجل

Global distribution: N Yemen and SW Saudi Arabia.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Al Haniq, Thamniyah [14], Wadi Dalaghan [16], Alogl, Wosanib [66], Asir National Park [75].

Recent records: Al Soudah, Raydah.

Habitat and ecology: This species is endemic to Yemen and south-western Saudi Arabia. Al-Khalili et al. [16] gave a comprehensive account on the ecology of the Yemen White-footed Rat. It was found at altitudes reaching 2100 m asl in areas covered by seasonal grasses such as Bromus spp., Chrysopogon sp., Pennisefum sp.) and with small trees of Vachellia tebaica and Lycium shawii shrubs [16]. Density estimates for this species ranged from 0.6 to 4.49 individuals per hectare. The home range ranged from 1375 to 1700 m2.

Biology: Khalili et al. [16] gave a comprehensive account on the biology of this species in Wadi Dalaghan in the Al Sarawat Mountains. Pregnancy was found to occur in December to March and from May to October. Lactating females were observed in April and June. The number of embryos ranged 4–6. This species was found to feed on a variety of items, including leaves, shoots, buds, and seed, as well as insects, spiders, spiny mouse of the genus Acomys, lizards, and Savigny’s green tree frog Hyla savignyi. The ectoparasites recorded from this species include X. conformis and R. sanguineus [16]. Stekolnikov et al. [45] described a new species of chigger mites, Schoutedenichia asirensis, from the Yemen White-footed Rat, in addition to other species.

Remarks: This species was previously listed as a subspecies of the African species Praomys fumatus, i.e., as Praomys fumatus yemeni. The taxonomic status of species of the subfamily Praomyini was revised, and the genus Myomyscus was referred to as a species found in South Africa [76]. Preliminary molecular studies showed the presence of two Ochromyscus species; one in the Afar Triangle and in eastern Ethiopia, referred to as Ochromyscus brockmani (Thomas, 1908), and the sister taxon, O. yemeni, from Yemen and southwestern Saudi Arabia [76].

Family Hystricidae

This family includes the Old World porcupines. The head and neck are covered with a crest of long bristles. The dorsal side is covered with spines of various sizes. Porcupines are nocturnal animals that feed entirely on roots, bulbs, and other cultivated crops.

Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792 (Figure 4F)

Common Name: Indian Crested Porcupine

Arabic name: النيص الهندي

Global distribution: Transcaucasus; Turkey; Arabia to S Kazakhstan and India; Sri Lanka; Tibet.

Distribution in Saudi Arabia:

Previous records: Harrat Al Harrah (Spines) [10], Turaif [12], between Abha-Al Darb, Al Qarrah, Khulays, Qalat Al Muazzam, Taif, Wadi Amag, Wadi Habagah, Wadi Hiswa, Wadi Hizma, Wadi Turabah [14], Jabal Shada [24], Median Salih [77], Summan [78], Abha, Al Masgi, Qunfuda, Riyadh, Tanuma [79].

Recent records: Al Baha, Al Khunfa, Al Juf, An Namas, Al Sarhan, Raydah, Rijal Alma’a, Wadi Arsha, Wadi Eia.

Habitat and ecology: The Indian Crested Porcupine favors rocky habitats with boulders and large and deep cervices. It lives in a wide variety of habitats, ranging from arid to humid areas in south-western Saudi Arabia. It occurs in the Asir and Hijaz mountains at elevations reaching 1400–1450 m a.s.l. [14]. It shelters in wadis of rocky nature and may live in small caves or in constructed burrows. Hystrix indica is a generalist, adaptable animal with a wide range of distribution. It also frequents farmlands in the vicinity of human habitations. It is found in relatively high numbers in groups of four individuals in An Namas. They are active after dusk [80].

Biology: The Indian Crested Porcupine is a colonial animal. A female gives birth to 2–4 young. Kingdon [29] observed the courtship behavior of H. indica: the female initiates courtship by moving closer towards the male in a proactive posture with the quills laid flat. They forage at night and can travel long distances away from their retreat.

3.2. Zoogeographical Affinities of the Rodents of Saudi Arabia

The zoogeography of the mammals of the Arabian Peninsula was presented by Delany [81]. His discussion was based on distributional data obtained before 1989 (Table 1). Recent studies expanded the known range for several species, which now allows us to discuss in detail the zoogeographic affinities of the rodents of Saudi Arabia.

Table 1.

Zoogeographical affinities of the rodents of Saudi Arabia.

Three species, G. nanus, M. crassus, and M. libycus, representing 15% of the rodents in Saudi Arabia, have a wide range of distribution throughout the Afrotropical–Palaearctic–Oriental range. Three species (15%) are endemic to Saudi Arabia and Yemen, i.e., G. poecilops, M. rex, and M. yemeni, while six species (30%), have Afrotropical–Palaearctic affinities (Table 1). Four species (20%) are considered to have Palaearctic affinities, i.e., J. loftusi, S. euphratica, G. cheesmani, and G. dasyurus. The Indian Crested porcupine is the only representative with Palaearctic–Oriental affinities. Three species are known as cosmopolitan species, i.e., R. rattus, R. norvegicus, and M. musculus.

3.3. Species Richness of Rodents in Saudi Arabia

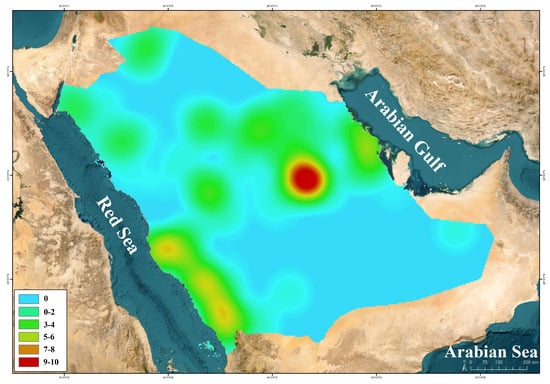

Figure 5 shows the species richness of the rodents across Saudi Arabia. The eastern central part of Saudi Arabia, covering the Tuwiq mountains plateau, including the vicinity of Riyadh, hosts the highest number of rodent species. This could be interpreted due to the several studies and collections made from this area. Also, it represents suitable habitats for several species of the genera Acomys, Gerbillus, and Meriones, and for Sekeetamys calurus, which was found only in this area, as well as for Jaculus loftusi. It is followed by the southwestern region, which includes three endemic species; however, there is no occurrence of desert-adapted species, including sand and gravel dwellers (i.e., G. cheesmani, G. henleyi, G. nanus, M. crassus, and M. libycus).

Figure 5.

Heat map showing rodent species richness in Saudi Arabia.

The other parts of Saudi Arabia host 3–6 species, according to habitat types. One species, A. dimidiatus, has a wide range of distribution that is associated with rocky and mountainous areas across the country. It was found along the Red Sea mountains, in sandstone deserts, and on the Tuwiq mountains plateau. Commensal and/or cosmopolitan species are associated with human settlements and farming areas.

3.4. Conservation of Rodents in Saudi Arabia

Most rodent species in Saudi Arabia were listed as least concern according to the IUCN Red List in both the global and Mediterranean assessments [82]; however, the national assessment of the rodents in Saudi Arabia listed some species as endangered such as the Euphrates Jerboa, S. euphraticus, and as near threatened for the Indian Crested Porcupine, H. indica. Three species are listed as data-deficient, while the rest are considered least concern (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conservation status of rodents in Saudi Arabia.

The Indian Crested Porcupine is considered a delicacy and is used in traditional medicine in many parts of Saudi Arabia [83] and the Middle East. It is being poached on a wide scale, causing a drastic decline of its population. In addition, farmers consider it a pest that causes damage to crops. This species is in trade and animals are offered for sale in Taif local markets. Several violations were issued for poaching this species in the Abha region. The Indian Crested porcupine is the only rodent species listed under the executive regulations for hunting wildlife organisms (No. 312179/1/1442). The fine for hunting H. indica is SAR 70,000 (about USD 18,600).

Populations of the Euphrates Jerboa, S. euphraticus, are declining in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere within its distribution range. It is one of the main prey items for desert owls. Locals relish the meat of jerboas, but this is practiced on a low scale. This species should be included in the hunting list of prohibited species. In some parts of Saudi Arabia, J. loftusi is hunted and consumed as a food item. It is also sold in local markets and used as bait in falconry. Local markets should be monitored to reduce the trade of this species. Falconers should be advised to abandon hunting using alive jerboas.

Habitat modifications and tourism in mountainous areas can pose a threat to Sekeetamys calurus, which is known from a few localities only.

There are no major threats to the three cosmopolitan species: M. musculus, R. rattus, and R. norvegicus. They are considered a serious pest to agriculture; they invade houses, farms, and storage areas; they cause severe financial losses; and they are associated with disease transmission.

Two of the endemic species, i.e., O. yemeni and M. rex, are not threatened as they seem to be abundant. On the contrary, little is known about G. poecilops since it is known from limited localities.

4. Discussion

The present study documents the rodent fauna of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with a total of 20 extant species. In comparison with the surrounding countries on the Arabian Peninsula, this number is relatively high, with the presence of three endemic species. A total of 28 extant species of rodents have been recorded from Iraq [84], 28 from Jordan [85], 5 Bahrain [86], 9 from Kuwait [87], 4 from Qatar [88], 10 from the United Arab Emirates [89], 13 from Oman [27,90], and 20 from Yemen [91]. The higher number of rodents in Iraq and Jordan is due to the presence of voles, squirrels, and temperate forest species of the genus Apodemus.

The status and biology of some endemic species, such as the Large Aden Gerbil, G. poecilops, in Saudi Arabia, require further investigation. Genetic variations among species with a wide range of distribution, such as Acomys dimidiatus, Eliomys melanurus, and Gerbillus dasyurus, deserve closer investigation.

More efforts to protect Hystrix indica and Scarturus euphraticus are among the highest priorities, and more enforcement is required to preserve these near-threatened and vulnerable species, respectively. On the other hand, the role of cosmopolitan species, which can sometimes become invasive, in disease transmission should be addressed, and control measures using environmentally friendly methods should be adopted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S.A., F.M.A. and K.A.A.M.; methodology and data collection, A.R.A.G., F.S., A.A.B., F.N. and S.A.J.; result analysis, Z.S.A., F.N., A.R.A.G., F.M.A. and K.A.A.M.; writing, Z.S.A., A.A.B., F.M.A., K.A.A.M. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Center for Wildlife (NCW), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are presented in the study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Center for Wildlife (NCW), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. We thank Mohammad Abu Baker, Carlos Bocos, Mark Jordan, Borut Rubinic, Adwan Shehab and Roland Wirth for providing images for some rodent species, Mohammad Al Nashiri and Abdul Majeed Alaqil from GIS unit (NCW) the preparation of maps. We acknowledge the records from the Immam Turki Ben Abdullah Reserve provided by Awad Al Juhani. Our thanks are extended to the anonymous referees for improving the manuscript. Authors wish to express their gratitude to Mohammed Qurban, CEO of NCW for his continuous support and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Locality | N | E | Locality | N | E |

| Abha | 18° 14′ | 42° 31′ | Kamis Mushayat | 18° 18′ | 42° 44′ |

| Abqaiq | 25° 57′ | 49° 41′ | Karan Island | 27° 43′ | 49° 50′ |

| Abu Ali Island | 27° 20′ | 49° 33′ | Khulays | 22° 09′ | 43° 55′ |

| Abu Hadriya | 27° 05′ | 49° 00′ | Kushm Buwaybiyat | 25° 12′ | 46° 52′ |

| Adama | 19° 19′ | 42° 04′ | Kushm Dibi | 24° 18′ | 46° 09′ |

| Adnan | 20° 26′ | 41° 31′ | Luga | 29° 46′ | 42° 38′ |

| Adwa | 27° 20′ | 42° 15′ | Mahazat as-Sayd | 22° 14′ | 41° 50′ |

| Aga | 27° 26′ | 41° 35′ | Makkah-Lith | 21° 22′ | 39° 38′ |

| Ajibba | 27° 20′ | 44° 20′ | Maqna | 28° 24′ | 34° 45′ |

| Al Aba Oasis | 26° 42′ | 49° 46′ | Medain Salih | 26° 50′ | 38° 00′ |

| Al Arf | 22° 01′ | 40° 55′ | Mekka by pass | 21° 15′ | 39° 42′ |

| Al Azizah | 18° 13′ | 42° 25′ | Nabek | 24° 27′ | 50° 49′ |

| Al Baha | 20° 01′ | 41° 28′ | Nabhaniyah | 25° 51′ | 43° 04′ |

| al Beda’a | 28° 29′ | 35° 02′ | Najran | 17° 30′ | 44° 20′ |

| Al Daba’ah | 28° 44′ | 37° 58′ | Neom | 28° 05′ | 35° 29′ |

| Al Dalhan | 18° 01′ | 43° 24′ | Nuayriyah | 27° 32′ | 48° 24′ |

| Al Hadda | 21° 26′ | 39° 35′ | Qaisumah | 28° 20′ | 46° 06′ |

| Al Haniq | 19° 45′ | 41° 57′ | Qalat Al Muazzam | 27° 44′ | 37° 30′ |

| Al Jawf | 29° 52′ | 39° 26′ | Qasab | 24° 14′ | 38° 53′ |

| Al Khardj | 23° 55′ | 47° 30′ | Qbah | 27° 24′ | 44° 20′ |

| Al Khubra | 25° 05′ | 43° 39′ | Qubat Al Zbair | 24° 52′ | 39° 56′ |

| Al Khunfa | 28° 38′ | 39° 19′ | Qunfidah | 19° 09′ | 41° 07′ |

| Al Masgi | 17° 58′ | 42° 52′ | Quwaywiyah | 23° 27′ | 44° 39′ |

| Al Na’amah | 20° 14′ | 41° 16′ | Ras al-Abkhara | 27° 24′ | 49° 14′ |

| Al Qarrah | 18° 07′ | 42° 42′ | Ras az Zaur | 27° 29′ | 49° 12′ |

| Al Qasab | 25° 24′ | 45° 47′ | Raudha Tinhat | 26° 15′ | 46° 00′ |

| Al Saiyarat | 27° 10′ | 44° 50′ | Raydah Protected Area | 18° 11′ | 42° 24′ |

| Al Sarhan | 18° 16′ | 42° 22′ | Rijal Alma’a | 18° 09′ | 42° 09′ |

| Al Souda | 18° 15′ | 42° 24′ | Risayah | 18° 57′ | 42° 11′ |

| Al Thumamah | 25° 22′ | 46° 36′ | Riyadh | 24° 30′ | 38° 49′ |

| Al Uquar | 25° 39′ | 50° 13′ | Rumah | 25° 37′ | 47° 07′ |

| Al Wajh | 26° 20′ | 37° 30′ | Rumaihiya | 25° 30′ | 47° 00′ |

| Alagan | 28° 23′ | 36° 33′ | Safaha Desert | 27° 19′ | 42° 23′ |

| Alogl | 18° 34′ | 42° 32′ | Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth | 22° 30′ | 42° 28′ |

| Alous | 18° 26′ | 42° 30′ | Salim | 23° 06′ | 42° 18′ |

| Alzobara | 27° 50′ | 41° 70′ | Sanam | 23° 42′ | 44° 45′ |

| An Namas | 19° 11′ | 42° 19′ | Sarhan | 18° 16′ | 42° 22′ |

| Anaiza | 26° 05′ | 44° 03′ | Sha’ib Al Shoki | 25° 42′ | 45° 51′ |

| Ar Rayn | 23° 32′ | 45° 30′ | Shaib al Tawqi | 25° 30′ | 46° 33′ |

| Artawiya | 26° 30′ | 45° 30′ | Shaib Hajlil | 27° 30′ | 44° 30′ |

| Ash Sharayi | 21° 40′ | 40° 40′ | Shaib Hanjur | 18° 15′ | 42° 45′ |

| Asir National Park | 18° 12′ | 42° 29′ | Sharma | 28° 01′ | 35° 13′ |

| Athnen | 18° 46′ | 42° 16′ | Shaybah | 22° 32′ | 53° 58′ |

| Bahara | 21° 23′ | 39° 27′ | Summan Plateau | 27° 00′ | 47° 00′ |

| Balum wells | 27° 15′ | 44° 00′ | SW Al Ula | 26° 38′ | 37° 54′ |

| Bani Musayqirah | 20° 21′ | 44° 30′ | Tabuk | 28° 23′ | 36° 36′ |

| Bani Sar | 20° 08′ | 41° 45′ | Taif | 21° 15′ | 40° 21′ |

| Barazan | 27° 52′ | 41° 70′ | Tala’a | 18° 04′ | 43° 57′ |

| between Abha-Al Darb | 18° 01′ | 42° 25′ | Tanomah | 18° 55′ | 42° 09′ |

| Birka | 27° 30′ | 44° 30′ | Thamami wells | 27° 40′ | 45° 00′ |

| Bsitah | 30° 44′ | 38° 31′ | Thamniya | 18° 01′ | 42° 45′ |

| Buridah | 26° 20′ | 43° 59′ | Todiah | 24° 12′ | 48° 03′ |

| Dailami | 20° 20′ | 42° 40′ | Tumeir | 25° 43′ | 45° 51′ |

| Dammam-Dhahran Rd. | 26° 16′ | 49° 59′ | Turaif | 31° 39′ | 38° 39′ |

| Dar el Harma | 26° 50′ | 38° 20′ | Tuwaiq Escarpment | 24° 23′ | 46° 30′ |

| Dauhat ad Dafi | 27° 03′ | 49° 24′ | Umm Ad Dabah | 23° 47′ | 45° 04′ |

| Dauhat al Musallamiya | 27° 26′ | 49° 12′ | Uruq Bani Ma’arid | 19° 20′ | 45° 54′ |

| Dirab | 24° 29′ | 46° 36′ | Wadi Amag | 18° 40′ | 42° 17′ |

| Duba | 27° 21′ | 35° 48′ | Wadi Arsha | 19° 45′ | 41° 36′ |

| Eljameayein | 27° 29′ | 41° 41′ | Wadi As Sulai | 24° 36′ | 46° 55′ |

| Elkhomashiya | 27° 28′ | 41° 42′ | Wadi Awsat | 24° 18′ | 46° 29′ |

| Farasan Al-Kebir | 16° 42′ | 41° 58′ | Wadi Bin Hashbal | 18° 58′ | 43° 06′ |

| Farasan Island | 16° 44′ | 41° 50′ | Wadi Dalaghan | 18° 02′ | 42° 50′ |

| Fayfa | 17° 15′ | 43° 06′ | Wadi Eia | 18° 52′ | 42° 28′ |

| Gariya | 27° 35′ | 47° 40′ | Wadi Habagah | 29° 47′ | 42° 40′ |

| Hafir Kishb | 22° 49′ | 41° 08′ | Wadi Hanifah | 24° 35′ | 46° 42′ |

| Hafr Al Batin | 28° 12′ | 46° 07′ | Wadi Hiswa | 18° 15′ | 42° 28′ |

| Hail | 27° 31′ | 41° 45′ | Wadi Hizma | 18° 05′ | 43° 56′ |

| Hamid | 18° 48′ | 42°56′ | Wadi Hureimala | 25° 06′ | 46° 05′ |

| Harrart Al Harrah | 30° 56′ | 39° 11′ | Wadi Karj | 24° 21′ | 47° 11′ |

| Hazm al Faidah | 27° 17′ | 49°1 0′ | Wadi Karrar | 21° 18′ | 40° 07′ |

| Hazm an-Nuquria | 27° 18′ | 49° 17′ | Wadi Khumra | 24° 55′ | 46° 11′ |

| Hesua | 18° 14′ | 42° 22′ | Wadi Liya | 21° 15′ | 40° 20′ |

| Hijla | 18° 15′ | 42° 38′ | Wadi Nissah | 24° 12′ | 46° 04′ |

| Hofuf | 21° 30′ | 39° 12′ | Wadi Qatan | 18° 07′ | 44° 07′ |

| Ibex Reserve | 23° 21′ | 46° 26′ | Wadi Rasid | 24° 17′ | 46° 16′ |

| Jabal Al Alam | 25° 36′ | 41° 04′ | Wadi Sanakhah | 18° 01′ | 44° 07′ |

| Jabal Al Aswad | 17° 39′ | 42° 39′ | Wadi Shaib Luha | 24° 25′ | 46° 48′ |

| Jabal Ammariyah | 24° 48′ | 46° 14′ | Wadi Sharayi | 21° 30′ | 39° 55′ |

| Jabal Banban | 25° 23′ | 46° 36′ | Wadi Shija | 24° 51′ | 46° 10′ |

| Jabal Farrash | 19° 37′ | 43° 26′ | Wadi Shuqub | 20° 40′ | 41° 15′ |

| Jabal Maniq | 24° 19′ | 46° 07′ | Wadi Sirhan | 18° 16′ | 42° 22′ |

| Jabal Shada | 19° 50′ | 41° 18′ | Wadi Thalham | 18° 24′ | 44° 08′ |

| Jabal Shar | 27° 23′ | 35° 27′ | Wadi Turabah | 20° 37′ | 41° 17′ |

| Jabal Thamamah | 25° 21′ | 46° 51′ | Wadi Uranah | 21° 21′ | 39° 57′ |

| Jana Island | 27° 22′ | 49° 18′ | Wadi Wajj | 21° 10′ | 40° 16′ |

| Jeddah | 21° 30′ | 39°12′ | Wosanib | 18° 34′ | 42° 23′ |

| Jizan | 16° 56′ | 42°33′ | |||

| Jubail | 26°57′ | 49° 34′ |

References

- Wilson, D.; Lacher, T.; Mittermeier, R. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 6 Lagomorphs and Rodents I; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; 987p. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.; Lacher, T.; Mittermeier, R. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 7 Rodents II; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; 1008p. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A.D.; Lightfoot, D.C.; McIntyre, J.L. Engineering rodents create key habitat for lizards. J. Arid Environ. 2008, 72, 2142–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, W.G.; Kay, F.R. Biopedturbation by mammals in deserts: A review. J. Arid Environ. 1999, 41, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesman, D.R.E.; Hinton, M.A.C. On the mammals collected in the desert of Central Arabia by Major R. E. Cheesman. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1924, 14, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesey-Fitzgerald, D. Notes on some rodents from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1953, 51, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.E.; Lewis, J.H.; Harrison, D.L. On a collection of mammals from northern Saudi Arabia. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1965, 144, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, D.; Nader, I.A. Pygmy shrew and rodents from the Near East. Senck. Biol. 1983, 64, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K. Noteworthy Mammal records from the Summan Plateau/NE Saudi Arabia. Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 1988, 90, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Seddo, P.J.; Heezik, Y.; Nader, I.A. Mammals of the Harrat al-Harrah protected area, Saudi Arabia. Zool. Middle East 1997, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M.W.; Shah, M.S.; Shobrak, M. Rodent trapping in the Saja/Umm Ar-Rimth Protected Area of Saudi Arabia using two different trap types. Zool. Middle East 2008, 43, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, B.A.; Al-Sadoon, M.K. A survey of mammal diversity in the Turaif province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Said, M.; Al-Zein, M.S. Rodents diversity in Wadi As Sulai, Riyadh Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Jordan J. Nat. Hist. 2022, 9, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Buttiker, W.; Harrison, D.L. Mammals of Saudi Arabia. On a collection of Rodentia from Saudi Arabia. Fauna Saudi Arab. 1982, 4, 488–502. [Google Scholar]

- Nader, I.A.; Kock, D.; Al-Khalili, A.D. Eliomys melanurus (Wagner, 1839) and Praomys fumatus (Peters, 1878) from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Mamnmalia: Rodentia). Senck. Biol. 1983, 63, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalili, A.D.; Delany, M.J.; Nader, I.A. The ecology of the rock rat, Praomys fumatus yemeni Sanborn and Hoogstraal, in Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 1988, 52, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarli, J.; Lutermann, H.; Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C. Reproductive patterns in the Baluchistan gerbil, Gerbillus nanus (Rodentia: Muridae), from western Saudi Arabia: The role of rainfall and temperature. J. Arid Environ. 2015, 113, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. Now you see me, now you don’t: The locomotory activity rhythm of the Asian garden dormouse (Eliomys melanurus) from Saudi Arabia. Mamm. Biol. 2014, 79, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. Down in the Wadi: The locomotory activity rhythm of the Arabian spiny mouse, Acomys dimidiatus from the Arabian Peninsula. J. Arid Environ. 2014, 102, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. A tale of two jirds: The locomotory activity patterns of the King jird (Meriones rex) and Lybian jird (Meriones lybicus) from Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 88, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N.; Mohammed, O.B.; Bennett, N.C.; Oosthuizen, M.K. Lights out, let’s move about: Locomotory activity patterns of Wagner’s Gerbil from the desert of Saudi Arabia. Afr. Zool. 2012, 47, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abi-Said, M.R.; Al Zein, M.S.; Abu Baker, M.A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of the desert eagle owl, Bubo ascalaphus, Savigny 1809 in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Zool. 2020, 52, 1169–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ahmary, A.; Al Obaid, A.; Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Shuraim, F.; Al Jbour, S.; Al Bough, A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of the Barn Owl, Tyto alba, from As Saqid Island, Farasan Archipelago, Saudi Arabia. Sandgrouse 2023, 45, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Alshammary, T.; Al Gethami, F.; Al Boug, A.; Al Jbour, S.; Amr, Z.S. Diet of Pharaoh Eagle Owl, Bubo ascalaphus, from Ara’r region, northeastern Saudi Arabia. Ornis Hung. 2023, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghamdi, A.-R.; Al Gethami, F.; Abu Baker, M.; Al Atawi, T.; Al Boug, A.; Amr, Z.S. Diet composition of the Pharaoh eagle owl, Bubo ascalaphus, diet across agricultural and natural areas in Saudi Arabia. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 83, e276117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgin, C.J.; Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Rylands, A.B.; Lacher, T.E.; Sechrest, W. Illustrated Checklist of the Mammals of the World; Lynx: Edicions, Barcelona, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.L.; Bates, P.J.J. The Mammals of Arabia, 2nd ed.; Harrison Zoological Museum Publication: Kent, UK, 1991; 354p. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, P. Desert Specialists: Arabia’s elegant mice. Arab. Wildl. 1996, 2, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S.; Abu Baker, M.A.; Qumsiyeh, M.; Eid, E. Systematics, distribution and ecological analysis of rodents in Jordan. Zootaxa 2018, 4397, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingdon, J. Arabian Mammals. A Natural History; Academic Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Atallah, S.I. Mammals of the Eastern Mediterranean: Their ecology, systematics and zoogeographical relationships. Säugetierkd. Mitt. 1978, 26, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalili, A.D. New records of ectoparasites of small rodents from SW Saudi Arabia. Fauna Saudi Arab. 1984, 6, 510–512. [Google Scholar]

- Khadhim, A.H.; Wahid, I.N. Reproduction of male Euphrates jerboa Allactaga euphratica Thomas (Rodentia: Dipodidae) from Iraq. Mammalia 1986, 50, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Bates, P. Diet of the Desert Eagle Owl in Harrat al Harrah reserve, northern Saudi Arabia. Ornithol. Soc. Middle East Bull. 1993, 30, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, O.; Dubost, G. Breeding periods of Gerbillus cheesmani (Rodentia, Muridae) in Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 2012, 76, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, D.; Nader, I. Terrestrial mammals of the Jubail Marine Wildlife Sanctuary. In Marine Wildlife Sanctuary for the Arabian Gulf: Environmental Research and Conservation Following the 1991 Gulf War Oil Spill; Krupp, F., Abuzinada, A.H., Nader, I.A.A., Eds.; National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia & Senckenbergische Naturforschende Gesellschaft: Frankfurt a.M., Germany, 1996; pp. 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, R.; Wacher, T.; Bruce, T.; Barichievy, C. The status and ecology of the sand cat in the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected Area, Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 2021, 85, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadim, A.H.; Mustafa, A.M.; Jabir, H.A. Biological notes on jerboas Allactaga euphratica and Jaculus jaculus from Iraq. Acta Theriol. 1979, 24, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- El Bahrawy, A.A.; Al Dakhil, M.A. Studies on the ectoparasites (fleas and lice) on rodents in Riyadh and its surroundings, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 1993, 23, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shenbrot, G.; Feldstein, T.; Meiri, S. Are cryptic species of the Lesser Egyptian Jerboa, Jaculus jaculus (Rodentia, Dipodidae), really cryptic? Re-evaluation of their taxonomic status with new data from Israel and Sinai. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2016, 54, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, A.A. Cytological studies of certain desert mammals of Saudi Arabia First report on chromosome number and karyotype of Acomys dimidiatus. Genetica 1988, 76, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmed, A.M.; Al-Dawood, A.S. Rodents and their ectoparasites in Wadi Hanifah, Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masseti, M. The mammals of the Farasan archipelago, Saudi Arabia. Turk. J. Zool. 2010, 34, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiry, K.A.; Fetoh, B.E.A. Occurrence of ectoparasitic arthropods associated with rodents in Hail region northern Saudi Arabia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 10120–10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stekolnikov, A.A.; Alghamdi, S.; Alagaili, A.N.; Makepeace, B.L. First data on chigger mites (Acariformes: Trombiculidae) of Saudi Arabia, with a description of four new species. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2019, 24, 1937–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghová, T.; Palupčíková, K.; Šumbera, R.; Frynta, D.; Lavrenchenko, L.A.; Meheretu, Y.; Sádlová, J.; Votýpka, J.; Mbau, J.S.; Modrý, D.; et al. Multiple radiations of spiny mice (Rodentia: Acomys) in dry open habitats of AfroArabia: Evidence from a multi-locus phylogeny. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, T.C.; Bennett, N.C.; Mohammed, O.B.; Alagaili, A.N. On the genetic diversity of spiny mice (genus Acomys) and gerbils (genus Gerbillus) in the Arabian Peninsula. Zool. Middle East 2013, 59, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.D.; Al-Mohammed, H.I.; Alyousif, M.S.; Said, A.E.; Salim, B.; Abdel-Shafy, S.; Shaapan, R.M. Species diversity and seasonal distribution of hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting mammalian hosts in various districts of Riyadh province. Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Entomol. 2019, 56, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkolnik, A.; Borut, A. Temperature and water relations in two species of spiny mice (Acomys). J. Mamm. 1969, 50, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, A. Studies in the Comparative Biology of Israel’s Two Species of Spiny Mice (Genus Acomys). Ph.D. Dissertation, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S.; Saliba, E.K. Ecological observations on the Fat Jird, Psammomys obesus dianae, in the Mowaqqar area of Jordan. Dirasat 1986, 13, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Baker, M.; Amr, Z. A morphometric and taxonomic revision of the genus Gerbillus in Jordan with notes on its current distribution. Zool. Abh. 2003, 53, 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- Schenbort, G.; Krasnov, B.; Khokhlova, I. Biology of Wagner’s gerbil, Gerbillus dasyurus (Wagner, 1842) (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) in the Negev Highlands, Israel. Mammalia 1997, 61, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenain, D.M.; Olfermann, E.; Warrington, S. Ecology, diet and behaviour of two fox species in a large, fenced protected area in central Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 2004, 57, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.I. A collection of mammals from El-Jafr, southern Jordan. Säugetierkd Mitt. 1967, 32, 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Schenbort, G.; Krasnov, B.; Khokhlova, I. On the biology of Gerbillus henleyi (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) in the Negev Highlands, Israel. Mammalia 1994, 58, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.M.; Dunstone, N. Environmental determinants of the composition of desert-living rodent communities in the north-east Badia region of Jordan. J. Zool. 2000, 251, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granjon, L. Genus Gerbillus Gerbils. In The Mammals of Africa; Happold, M., Happold, D.C.D., Eds.; Rodents, Hares and Rabbits, Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2013; Volume III, pp. 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Scott, T.C.S. Some Arabian mammals collected by Mr. H. St. J.B. Philby: C.I.E. Novit. Zool. 1939, 41, 181–211. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Dieyeh, M.H. The Ecology of Some Rodents in Wadi Araba with Special Reference to Acomys cahirinus. Master’s Thesis, Jordan University, Amman, Jordan, 1988; 216p. [Google Scholar]

- Qumsiyeh, M.B. Mammals of the Holy Land; Texas Tech University Press: Lubbock, TX, USA, 1996; 389p. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnov, B.R.; Shenbrot, G.I.; Khokhlova, I.S.; Degen, A.A.; Rogovin, K.A. On the biology of Sundevall’s jird (Meriones crassus Sundevall, 1842) (Rodentia: Gerbillidae) in the Negev Highlands, Israel. Mammalia 1996, 60, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, S.I. Mammals of the Eastern Mediterranean: Their ecology, systematics and zoogeographical relationships. Säugetierkd. Mitt. 1977, 25, 241–320. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, D.J.; Helmy, I. The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai). Fieldiana Zool. 1980, 5, 1–579. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerman, J.R. Key to the rodents of south-west Asia in the British Museum collection. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1948, 118, 765–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S. The Vector Biology and Microbiome of Parasitic Mites and Other Ectoparasites of Rodents. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2019; 328p. [Google Scholar]

- 67 Al-Saleh, A.A.; Khan, M.A. Cytological studies of certain desert mammals of Saudi Arabia: The karyotype of Meriones rex. Genetica 1987, 73, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, T.A.; El Bahrawy, A.F.; El Dakhil, M.A. Ecto- and blood parasites affecting Meriones rex trapped in Najran, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Mohammed, H.I. Taxonomical studies of ticks infesting wild rodents from Asir Province in Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, A.; Robb, G.N.; Alagaili, A.N.; Hastriter, M.W.; Apanaskevich, D.A.; Ueckermann, E.A.; Bennett, N.C. Ectoparasite fauna of rodents collected from two wildlife research centres in Saudi Arabia with discussion on the implications for disease transmission. Acta Trop. 2015, 147, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, B. Die Muriden von Palästina und Syrien. Z. Säugetierkd. 1932, 7, 166–240. [Google Scholar]

- Nader, I.A. A new record of the bushy-tailed jird, Sekeetamys calurus calurus Thomas, 1892 from Saudi Arabia. Mammalia 1974, 38, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shargal, E.; Kronfeld, N.; Dayan, T. On the population ecology of the bushy-tailed jird (Sekeetamys calurus) at En Gedi. Isr. J. Zool. 1998, 44, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffen, E.; Hefner, R.; MacDonald, D.W.; Ucko, M. Diet and foraging behavior of Blanford’s foxes, Vulpes cana, in Israel. J. Mamm. 1992, 73, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, A.D. Ecology of Small Rodents in the Asir National Park, Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bradford, Bradford, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, V.; Mikula, O.; Lavrenchenko, L.A.; Šumbera, R.; Bartáková, V.; Bryjová, A.; Bryja, J. Phylogenomics of African radiation of Praomyini (Muridae: Murinae) rodents: First fully resolved phylogeny, evolutionary history and delimitation of extant genera. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2021, 163, 107263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughty, C.M. Travels in Arabia Deserta; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1888; 674p. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, H.R.P. The Arab of the Desert; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1949; 664p. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Safadi, M.M.; Nader, I.A. The Indian crested porcupine, Hystrix indica indica Kerr, 1792 in North Yemen with comments on the occurrence of the species in the Arabian Peninsula (Mammalia: Rodentia: Hystricidae). Fauna Saudi Arab. 1991, 12, 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, P.U.; Saltz, D. Influence of season and moonlight on temporal-activity patterns of Indian crested porcupines (Hystrix indica). J. Mamm. 1988, 69, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delany, M.J. The zoogeography of the mammal fauna of southern Arabia. Mamm. Rev. 1989, 19, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, H.J.; Cuttelod, A. The Status and Distribution of Mediterranean Mammals; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2009; vii+32p. [Google Scholar]

- Aloufi, A.; Eid, E. Zootherapy: A study from the Northwestern region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016, 15, 561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheikhly, O.F.; Haba, M.K.; Barbanera, F.; Csorba, G.; Harrison, D.L. Checklist of the mammals of Iraq (Chordata: Mammalia). Bonn Zool. Bull. 2015, 64, 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Amr, Z.S. The Mammals of Jordan, 2nd ed.; Al Rai Press: Amman, Jordan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AI-Khalili, A.D. New records and a review of the mammalian fauna of the State of Bahrain, Arabian Gulf. J. Arid Environ. 1990, 19, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Baker, M.A.; Buhadi, Y.A.; Alenezi, A.; Amr, Z.S. Mammals of the State of Kuwait; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Environment Public Authority: Al Asmiah, Kuwait, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, A.; Madkour, G. New records of some mammals from Qatar: Insectivora, Lagomorpha and Rodentia. Qatar Univ. Sci. Bull. 1984, 4, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, P.L. Checklist and status of the terrestrial mammals from the United Arab Emirates. Zool. Middle East 2004, 33, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.C.; Pardiñas, U.F.J. First record of the bushy-tailed jird, Sekeetamys calurus (Thomas, 1892) (Rodentia: Muridae) in Oman. Mammalia 2016, 80, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensoor, M. The mammals of Yemen (Chordata: Mammalia). Preprints 2023, 2023010181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).