A Comparative Analysis of Island vs. Mainland Arthropod Communities in Coastal Grasslands Belonging to Two Distinct Regions: São Miguel Island (Azores) and Mainland Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

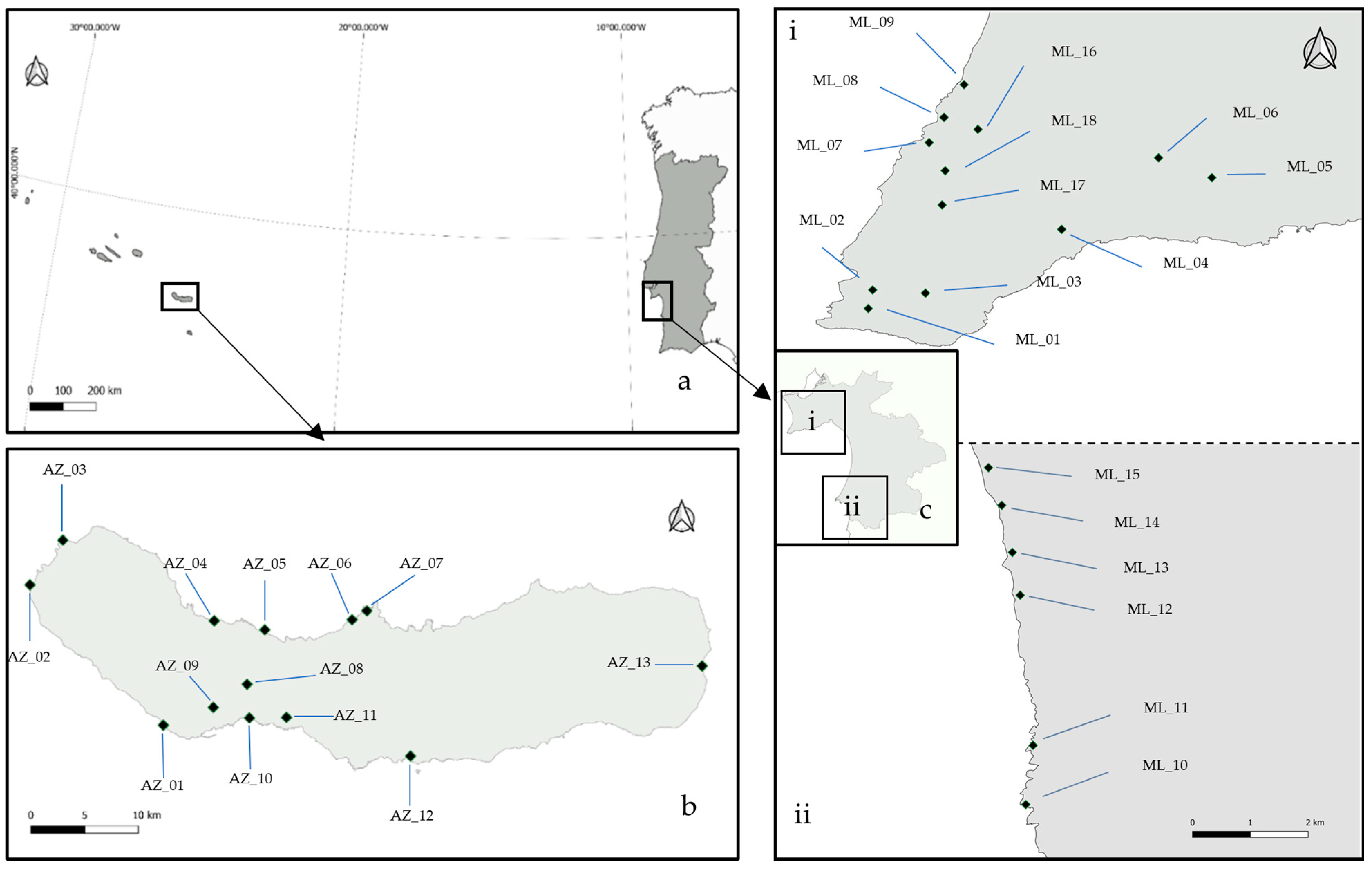

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Arthropod Sampling

2.3. Species Sorting, Identification, and Diversity Measurements

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

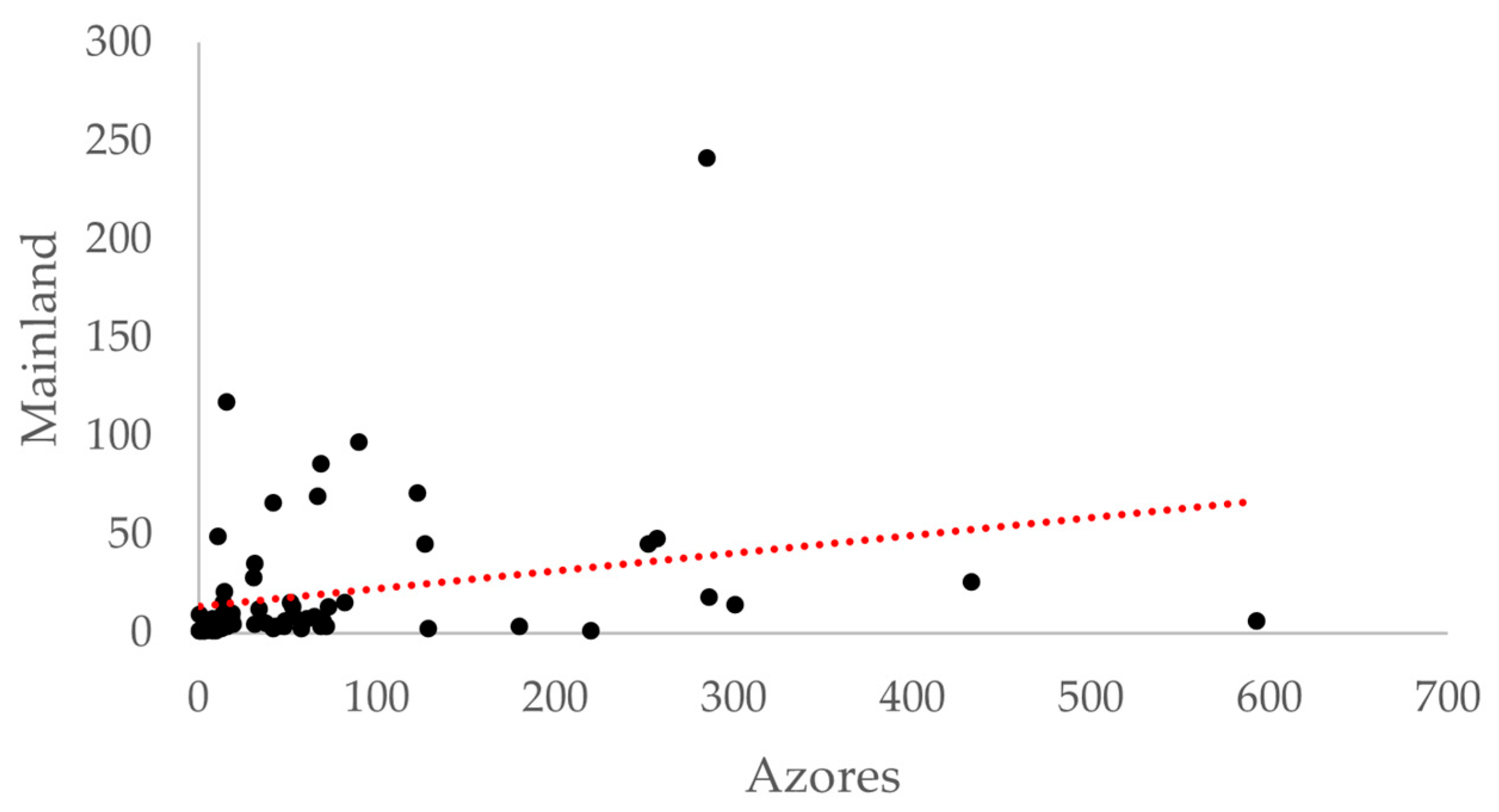

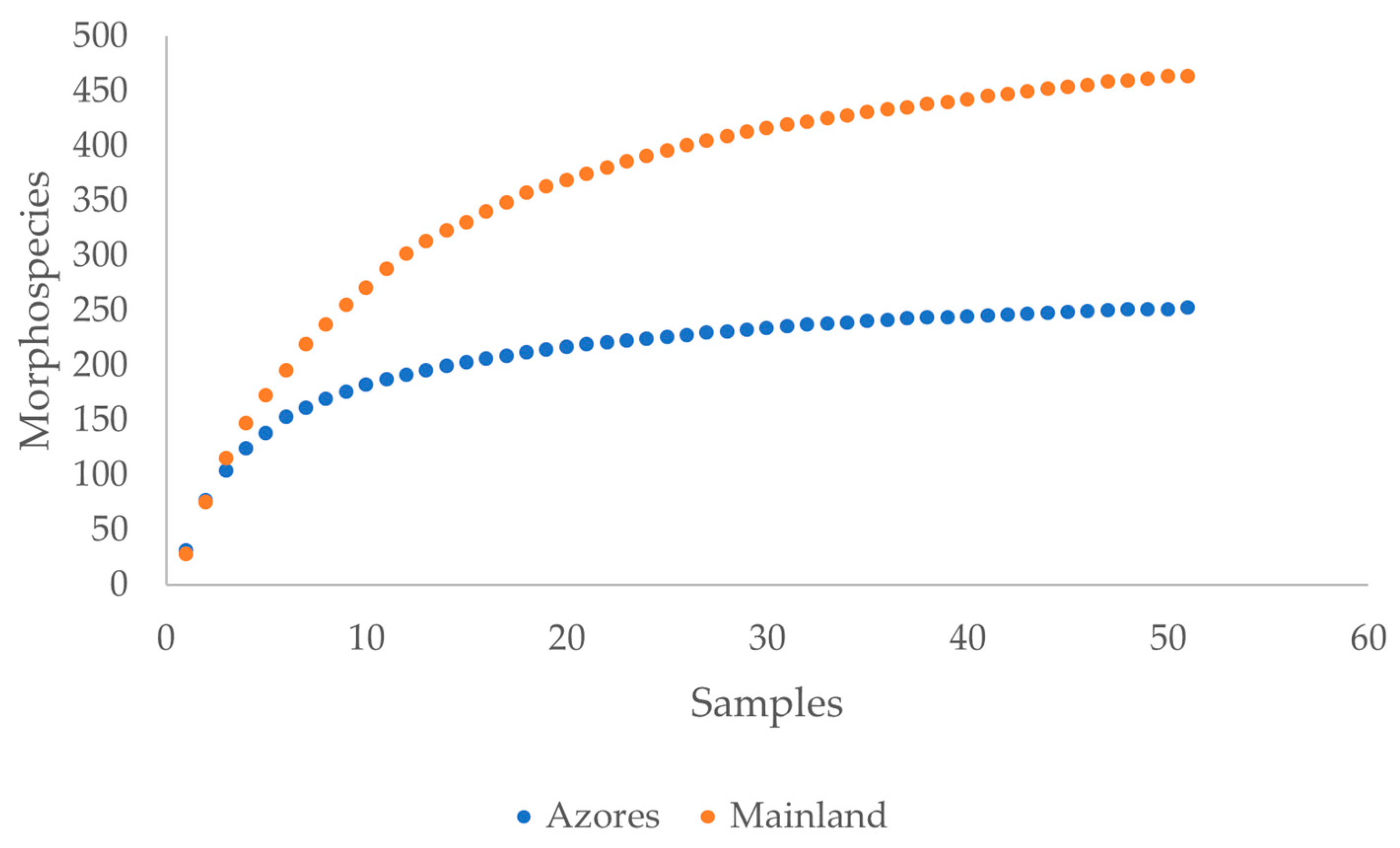

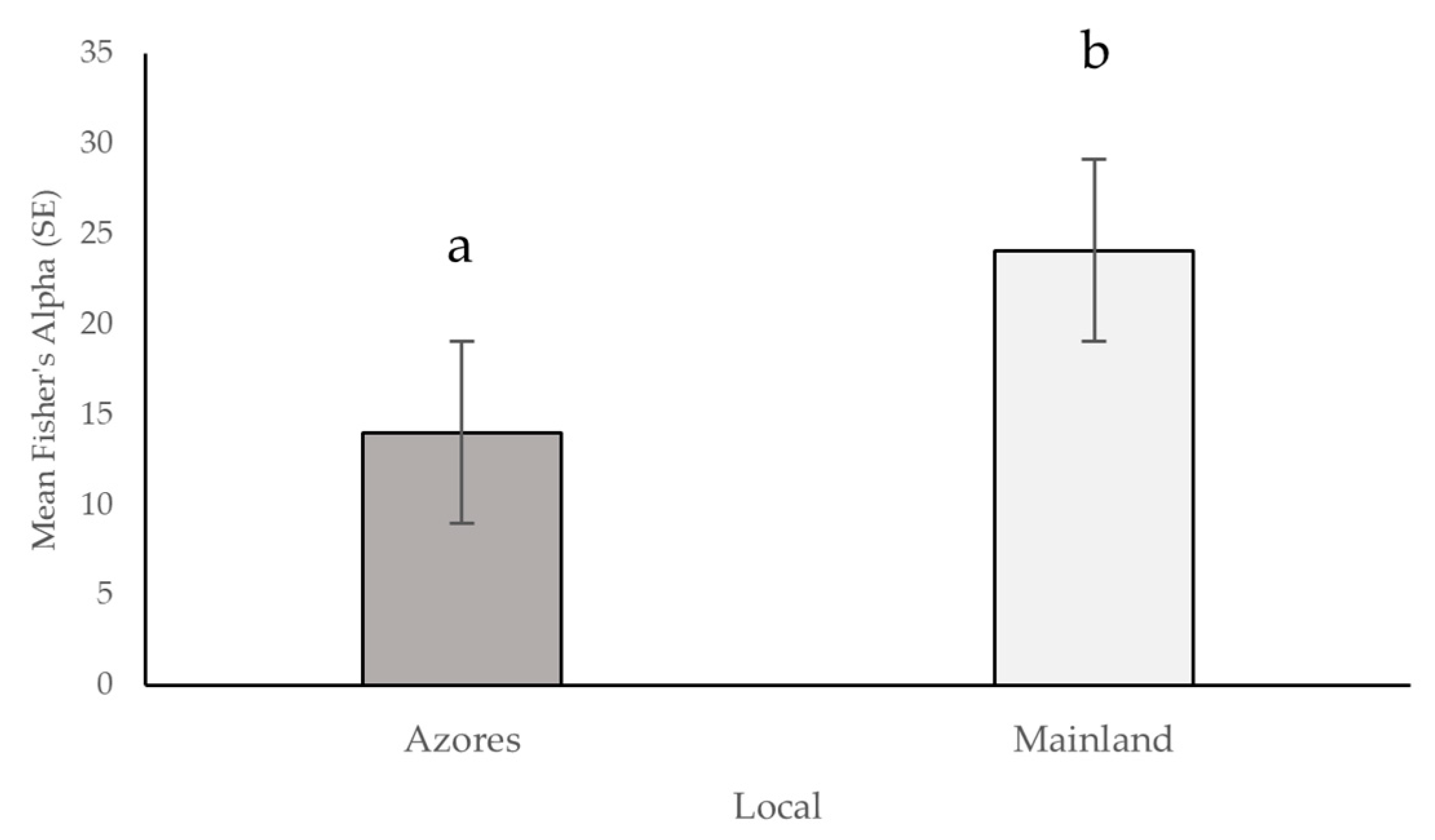

3.1. Species Richness and Abundance

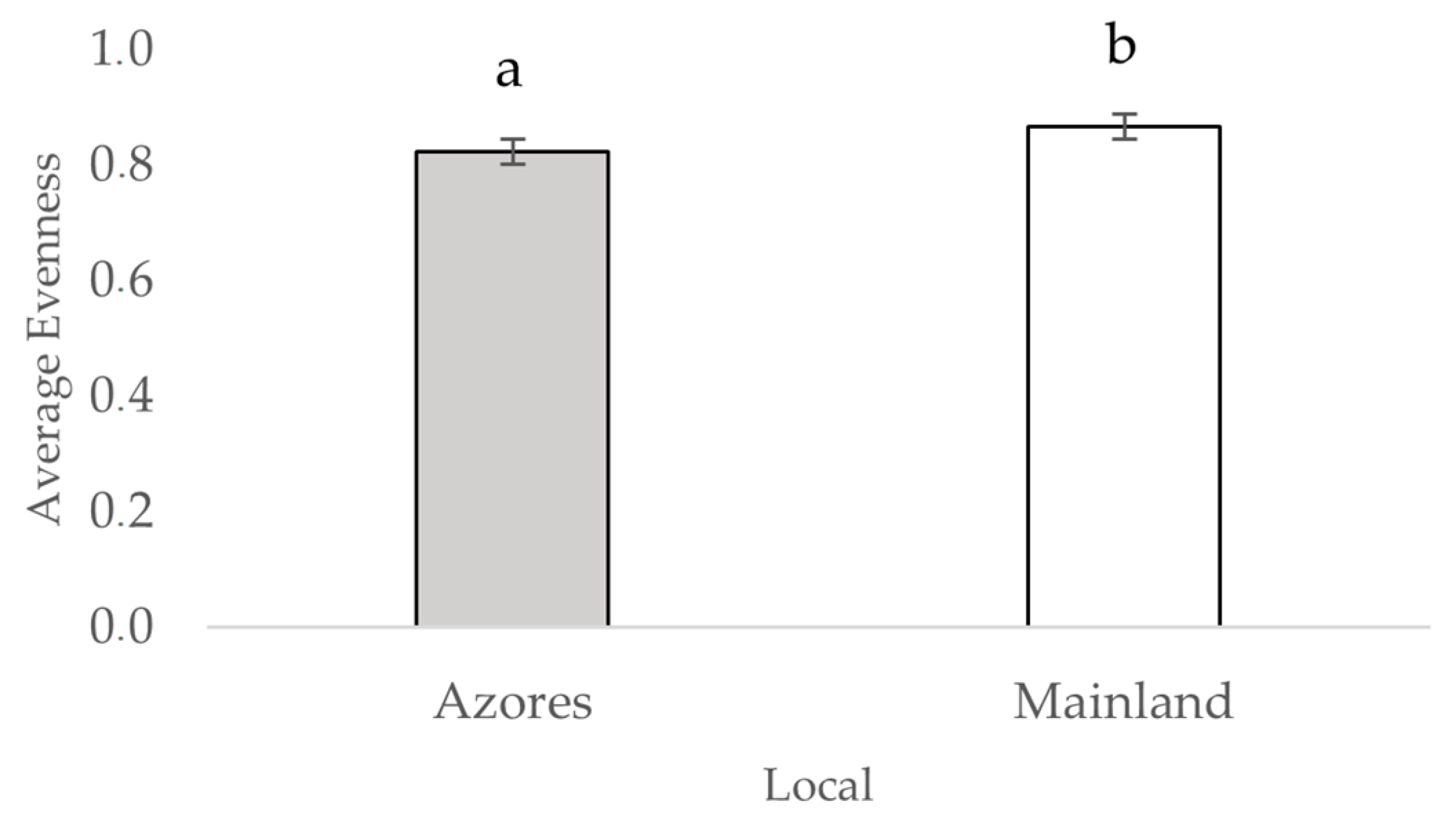

3.2. Diversity Metrics for the Arthropod Communities of the Azores and Mainland Coastal Grasslands (Hill Series)

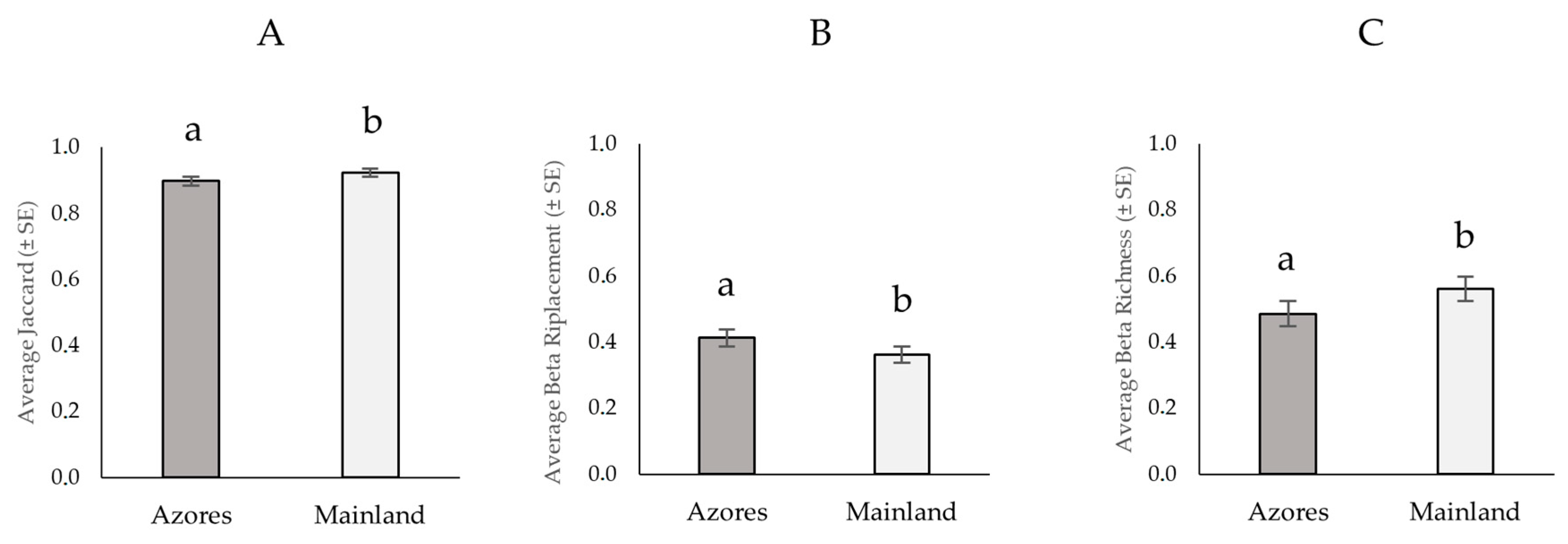

3.3. Dissimilarity Index (Jaccard)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Location ID | Coordinates | Locality |

|---|---|---|

| AZ_01 | 37°44′48″ N 25°42′46″ W | Relva |

| AZ_02 | 37°51′40″ N 25°51′12″ W | Ferraria |

| AZ_03 | 37°53′57″ N 25°49′04″ W | Mosteiros |

| AZ_04 | 37°49′53″ N 25°39′30″ W | São Vicente |

| AZ_05 | 37°49′26″ N 25°36′15″ W | Calhetas |

| AZ_06 | 37°50′05″ N 25°30′40″ W | Ribeira Grande |

| AZ_07 | 37°50′31″ N 25°30′01″ W | Ribeirinha |

| AZ_08 | 37°46′43″ N 25°37′25″ W | Ponta Delgada |

| AZ_09 | 37°45′34″ N 25°39′31″ W | Ponta Delgada |

| AZ_10 | 37°45′00″ N 25°37′17″ W | Ponta Delgada |

| AZ_11 | 37°45′05″ N 25°34′58″ W | Lagoa |

| AZ_12 | 37°43′07″ N 25°27′04″ W | Vila Franca do Campo |

| AZ_13 | 37°47′37″ N 25°11′34″ W | Fajã do Araújo |

| ML_01 | 38°25′01″ N 9°12′43″ W | Cabo Espichel |

| ML_02 | 38°25′11″ N 9°12′42″ W | Cabo Espichel |

| ML_03 | 38°25′12″ N 9°12′04″ W | Cabo Espichel |

| ML_04 | 38°25′56″ N 9°10′25″ W | Azoia |

| ML_05 | 38°26′32″ N 9°08′42″ W | Azoia |

| ML_06 | 38°26′47″ N 9°09′17″ W | Azoia |

| ML_07 | 38°26′58″ N 9°12′01″ W | Meco |

| ML_08 | 38°27′16″ N 9°11′51″ W | Meco |

| ML_09 | 38°27′43″ N 9°11′34″ W | Meco |

| ML_10 | 37°50′59″ N 8°47′41″ W | Porto Covo |

| ML_11 | 37°51′42″ N 8°47′36″ W | Porto Covo |

| ML_12 | 37°53′27″ N 8°47′45″ W | Porto Covo |

| ML_13 | 37°53′57″ N 8°47′52″ W | Sines |

| ML_14 | 37°54′30″ N 8°47′58″ W | Sines |

| ML_15 | 37°54′57″ N 8°48′08″ W | Sines |

| ML_16 | 38°27′08″ N 9°11′27″ W | Meco |

| ML_17 | 38°26′13″ N 9°11′52″ W | Azoia |

| ML_18 | 38°26′38″ N 9°11′50″ W | Azoia |

| MS ID | Class | Order | Family | Azores | Mainland | Establishment Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 42 | 66 | I |

| 102 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 16 | 117 | NA |

| 138 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 8 | 1 | I |

| 279 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 282 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 284 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 22 | NA |

| 306 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 307 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 308 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 316 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 12 | NA |

| 318 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 347 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 447 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 477 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 519 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 530 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 722 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 723 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 725 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 8 | 0 | NA |

| 728 | Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 374 | Arachnida | Araneae | Cheiracanthiidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 446 | Arachnida | Araneae | Dictynidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 349 | Arachnida | Araneae | Gnaphosidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 375 | Arachnida | Araneae | Gnaphosidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 605 | Arachnida | Araneae | Gnaphosidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 32 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 25 | 0 | I |

| 33 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 52 | 15 | I |

| 130 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 18 | 0 | N |

| 131 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 11 | 4 | I |

| 312 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 350 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 0 | 29 | NA |

| 370 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 0 | 41 | NA |

| 371 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 596 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 597 | Arachnida | Araneae | Linyphiidae | 0 | 16 | NA |

| 310 | Arachnida | Araneae | Lycosidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 407 | Arachnida | Araneae | Lycosidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 529 | Arachnida | Araneae | Lycosidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 317 | Arachnida | Araneae | Philodromidae | 0 | 12 | NA |

| 329 | Arachnida | Araneae | Philodromidae | 0 | 23 | NA |

| 445 | Arachnida | Araneae | Philodromidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 553 | Arachnida | Araneae | Pisauridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 18 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 73 | 13 | I |

| 45 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 31 | 28 | I |

| 85 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 61 | 7 | I |

| 104 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 16 | 6 | N |

| 313 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 551 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 552 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 563 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 724 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 729 | Arachnida | Araneae | Salticidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 265 | Arachnida | Araneae | Tetragnathidae | 0 | 52 | NA |

| 437 | Arachnida | Araneae | Tetragnathidae | 52 | 0 | NA |

| 726 | Arachnida | Araneae | Tetragnathidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 278 | Arachnida | Araneae | Theridiidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 311 | Arachnida | Araneae | Theridiidae | 0 | 18 | NA |

| 368 | Arachnida | Araneae | Theridiidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 518 | Arachnida | Araneae | Theridiidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 606 | Arachnida | Araneae | Theridiidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 17 | Arachnida | Araneae | Thomisidae | 90 | 97 | I |

| 315 | Arachnida | Araneae | Thomisidae | 0 | 32 | NA |

| 373 | Arachnida | Araneae | Thomisidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 440 | Arachnida | Araneae | Thomisidae | 0 | 59 | NA |

| 727 | Arachnida | Araneae | Thomisidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 76 | Arachnida | Opiliones | Leiobunidae | 32 | 0 | N |

| 548 | Arachnida | Opiliones | Phalangiidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 143 | Diplopoda | Julida | Julidae | 1 | 0 | I |

| 61 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Apionidae | 72 | 3 | I |

| 478 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Cantharidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 488 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Cantharidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 354 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Carabidae | 0 | 65 | NA |

| 539 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Carabidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 542 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Carabidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 591 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Carabidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 421 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Cerambycidae | 0 | 49 | NA |

| 429 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Cerambycidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 23 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 11 | 49 | N |

| 71 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 12 | 0 | I |

| 106 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 30 | 0 | I |

| 208 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 2 | 0 | I |

| 215 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 8 | 0 | N |

| 239 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 20 | 0 | I |

| 280 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 20 | NA |

| 289 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 15 | NA |

| 327 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 32 | NA |

| 366 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 367 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 72 | NA |

| 381 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 24 | NA |

| 401 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 16 | NA |

| 417 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 18 | NA |

| 435 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 10 | NA |

| 450 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 25 | NA |

| 455 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 51 | NA |

| 459 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 15 | NA |

| 462 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 469 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 476 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 480 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 491 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 44 | NA |

| 525 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 62 | NA |

| 544 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 545 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 547 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 574 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 585 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 587 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 592 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 598 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 28 | NA |

| 600 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 602 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 604 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Chrysomelidae | 0 | 14 | NA |

| 40 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 37 | 0 | I |

| 111 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 129 | 2 | I |

| 135 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 38 | 5 | N |

| 154 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 22 | 0 | I |

| 155 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 2 | 0 | N |

| 156 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 2 | 1 | I |

| 231 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 0 | 24 | NA |

| 233 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 361 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 426 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 0 | 16 | NA |

| 466 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 573 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 603 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Coccinellidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 67 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Cryptophagidae | 1 | 0 | I |

| 599 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Cryptophagidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 81 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 10 | 0 | I |

| 101 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 6 | 0 | I |

| 136 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 286 | 18 | I |

| 243 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 2 | I |

| 274 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 277 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 299 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 321 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 15 | NA |

| 332 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 357 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 358 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 359 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 360 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 12 | NA |

| 427 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 448 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 473 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 486 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 508 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 579 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 580 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 581 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 594 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 336 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Dasytidae | 0 | 202 | NA |

| 495 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Dermestidae | 0 | 107 | NA |

| 496 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Dryophthoridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 234 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Elateridae | 2 | 0 | E |

| 353 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Elateridae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 414 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Elateridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 556 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Elateridae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 576 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Elateridae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 339 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Malachiidae | 0 | 21 | NA |

| 419 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Malachiidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 513 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Malachiidae | 0 | 42 | NA |

| 422 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Melyridae | 0 | 14 | NA |

| 460 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Melyridae | 0 | 25 | NA |

| 528 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Melyridae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 451 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Mordellidae | 0 | 130 | NA |

| 52 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 54 | 8 | I |

| 75 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 26 | 0 | I |

| 192 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 10 | 0 | NA |

| 301 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 0 | 47 | NA |

| 356 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 402 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 601 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 720 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Nitidulidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 461 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Oedemeridae | 0 | 20 | NA |

| 489 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Oedemeridae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 41 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Phalacridae | 14 | 10 | N |

| 340 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Phalacridae | 0 | 10 | NA |

| 501 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Phalacridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 566 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Phalacridae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 567 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Phalacridae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 535 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Rutelidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 540 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Rutelidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 394 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Scarabaeidae | 0 | 17 | NA |

| 22 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 115 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 1 | 1 | NA |

| 134 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 8 | 0 | I |

| 213 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 291 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 351 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 352 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 543 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Staphylinidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 487 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Tenebrionidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 507 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Tenebrionidae | 0 | 24 | NA |

| 520 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Tenebrionidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 593 | Insecta | Coleoptera | Tenebrionidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 26 | Insecta | Diptera | Agromyzidae | 64 | 0 | NA |

| 126 | Insecta | Diptera | Agromyzidae | 10 | 1 | NA |

| 616 | Insecta | Diptera | Agromyzidae | 0 | 26 | NA |

| 53 | Insecta | Diptera | Calliphoridae | 16 | 3 | NA |

| 194 | Insecta | Diptera | Calliphoridae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 560 | Insecta | Diptera | Calliphoridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 453 | Insecta | Diptera | Carnidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 7 | Insecta | Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | 44 | 0 | NA |

| 624 | Insecta | Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | 0 | 20 | NA |

| 8 | Insecta | Diptera | Chloropidae | 32 | 35 | NA |

| 150 | Insecta | Diptera | Chloropidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 15 | Insecta | Diptera | Drosophilidae | 102 | 0 | NA |

| 27 | Insecta | Diptera | Drosophilidae | 79 | 0 | NA |

| 615 | Insecta | Diptera | Drosophilidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 617 | Insecta | Diptera | Drosophilidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 43 | Insecta | Diptera | Hybotidae | 5 | 0 | NA |

| 159 | Insecta | Diptera | Hybotidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 619 | Insecta | Diptera | Hybotidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 622 | Insecta | Diptera | Hybotidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 34 | Insecta | Diptera | Lauxaniidae | 7 | 0 | NA |

| 618 | Insecta | Diptera | Lauxaniidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 46 | Insecta | Diptera | Lonchopteridae | 67 | 69 | NA |

| 3 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 123 | 71 | NA |

| 14 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 69 | 0 | NA |

| 30 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 65 | 8 | NA |

| 142 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 70 | 6 | NA |

| 151 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 166 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 5 | 0 | NA |

| 177 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 214 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 225 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 95 | 0 | NA |

| 230 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 263 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 614 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 57 | NA |

| 621 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 623 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 112 | NA |

| 625 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 626 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 721 | Insecta | Diptera | Muscidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 127 | Insecta | Diptera | Opomyzidae | 4 | 3 | NA |

| 28 | Insecta | Diptera | Rhinophoridae | 82 | 15 | NA |

| 2 | Insecta | Diptera | Scathophagidae | 52 | 0 | NA |

| 181 | Insecta | Diptera | Sciaridae | 23 | 0 | NA |

| 627 | Insecta | Diptera | Sciaridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 10 | Insecta | Diptera | Sepsidae | 352 | 0 | NA |

| 144 | Insecta | Diptera | Sepsidae | 82 | 0 | NA |

| 161 | Insecta | Diptera | Sepsidae | 59 | 0 | NA |

| 193 | Insecta | Diptera | Sepsidae | 6 | 0 | NA |

| 613 | Insecta | Diptera | Sepsidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 575 | Insecta | Diptera | Stratiomyidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 4 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 15 | 7 | NA |

| 5 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 34 | 12 | NA |

| 56 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 4 | 3 | NA |

| 205 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 254 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 258 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 288 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 294 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 383 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 550 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 628 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 0 | 15 | NA |

| 629 | Insecta | Diptera | Syrphidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 55 | Insecta | Diptera | Tephritidae | 77 | 0 | NA |

| 210 | Insecta | Diptera | Tephritidae | 220 | 1 | NA |

| 335 | Insecta | Diptera | Tephritidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 386 | Insecta | Diptera | Tephritidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 514 | Insecta | Diptera | Tephritidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 620 | Insecta | Diptera | Tephritidae | 0 | 31 | NA |

| 29 | Insecta | Diptera | Tipulidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 204 | Insecta | Diptera | Tipulidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 490 | Insecta | Diptera | Ulidiidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 433 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Alydidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 125 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 44 | 3 | I |

| 140 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 16 | 0 | NA |

| 203 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 293 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 314 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 380 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 410 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 523 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 6 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 257 | 48 | N |

| 16 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 42 | 2 | NA |

| 24 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 58 | 2 | NA |

| 88 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 127 | 45 | N |

| 89 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 31 | 0 | N |

| 108 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 13 | 0 | N |

| 112 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 1 | 0 | N |

| 124 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 19 | 10 | N |

| 376 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 13 | 0 | NA |

| 474 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphididae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 50 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphrophoridae | 285 | 241 | I |

| 319 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphrophoridae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 387 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphrophoridae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 467 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Aphrophoridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 465 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Blissidae | 0 | 43 | NA |

| 31 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 185 | 0 | NA |

| 113 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 57 | 0 | I |

| 133 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 301 | 14 | NA |

| 189 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 35 | 0 | N |

| 236 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 8 | 0 | NA |

| 244 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 1 | 0 | I |

| 245 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 17 | 0 | N |

| 253 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 1 | 0 | N |

| 257 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 342 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 1 | 0 | N |

| 369 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 378 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 0 | 25 | NA |

| 393 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 470 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 483 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 522 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 48 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cixiidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 272 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cixiidae | 0 | 14 | NA |

| 409 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cixiidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 423 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cixiidae | 0 | 15 | NA |

| 418 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Coreidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 479 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Coreidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 412 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Cydnidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 12 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 243 | 0 | N |

| 49 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 252 | 45 | N |

| 77 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 44 | 3 | N |

| 271 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 331 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 428 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 557 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Delphacidae | 0 | 20 | NA |

| 153 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Flatidae | 3 | 0 | N |

| 328 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Flatidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 114 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Liviidae | 1 | 0 | E |

| 20 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Lygaeidae | 49 | 6 | N |

| 51 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Lygaeidae | 40 | 0 | NA |

| 141 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Lygaeidae | 14 | 15 | N |

| 338 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Lygaeidae | 0 | 19 | NA |

| 341 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Lygaeidae | 0 | 12 | NA |

| 355 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Lygaeidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 87 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 433 | 26 | N |

| 195 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 3 | 0 | N |

| 211 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 74 | 0 | NA |

| 413 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 438 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 569 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 571 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Miridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 58 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Nabidae | 27 | 0 | N |

| 72 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Nabidae | 180 | 3 | N |

| 377 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Nabidae | 0 | 100 | NA |

| 439 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Oxycarenidae | 1 | 0 | I |

| 117 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Pentatomidae | 53 | 13 | I |

| 408 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Pentatomidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 430 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Pentatomidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 463 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Pentatomidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 500 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Pentatomidae | 0 | 12 | NA |

| 68 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Psyllidae | 15 | 21 | I |

| 546 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Psyllidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 379 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Reduviidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 396 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Reduviidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 406 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Reduviidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 524 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Reduviidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 531 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Reduviidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 554 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Reduviidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 443 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Rhopalidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 504 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Rhopalidae | 0 | 10 | NA |

| 532 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Rhopalidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 198 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Rhyparochromidae | 2 | 0 | N |

| 218 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Rhyparochromidae | 1 | 9 | N |

| 588 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Rhyparochromidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 19 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Saldidae | 4 | 1 | N |

| 589 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Saldidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 475 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Scutelleridae | 0 | 22 | NA |

| 568 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Tettigometridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 411 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Tingidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 492 | Insecta | Hemiptera | Tingidae | 0 | 10 | NA |

| 9 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Aphelinidae | 96 | 0 | NA |

| 93 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Aphelinidae | 10 | 0 | NA |

| 128 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Aphelinidae | 9 | 2 | NA |

| 561 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Aphelinidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 661 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Aphelinidae | 0 | 587 | NA |

| 35 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 19 | 6 | I |

| 36 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 16 | 3 | NA |

| 345 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 390 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 399 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 549 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 559 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 572 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 578 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Apidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 13 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 16 | 0 | NA |

| 25 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 55 | 0 | NA |

| 109 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 207 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 251 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 276 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 645 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 0 | 12 | NA |

| 653 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 660 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 662 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 663 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Braconidae | 0 | 22 | NA |

| 485 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Chalcididae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 389 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Colletidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 502 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Colletidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 674 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Colletidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 47 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Encyrtidae | 5 | 0 | NA |

| 91 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Encyrtidae | 13 | 2 | NA |

| 121 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Encyrtidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 123 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Encyrtidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 646 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Encyrtidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 665 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Encyrtidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 100 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Eulophidae | 6 | 4 | NA |

| 122 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Eulophidae | 69 | 86 | NA |

| 536 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Eumenidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 42 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 7 | 0 | NA |

| 97 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 157 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 7 | 0 | NA |

| 343 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 595 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 643 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 644 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 648 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Figitidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 21 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 593 | 6 | N |

| 44 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 5 | 5 | N |

| 137 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 20 | 4 | N |

| 139 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 30 | 0 | N |

| 219 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 12 | 0 | I |

| 220 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 2 | 0 | N |

| 241 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 9 | 0 | N |

| 262 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 177 | NA |

| 268 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 50 | NA |

| 292 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 18 | NA |

| 320 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 322 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 20 | NA |

| 425 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 436 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 449 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 464 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 482 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 654 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 657 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 669 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 672 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Formicidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 37 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 113 | 0 | NA |

| 145 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 30 | 0 | NA |

| 190 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 5 | 0 | NA |

| 362 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 388 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 441 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 456 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 512 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 652 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 664 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 19 | NA |

| 670 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Halictidae | 0 | 15 | NA |

| 38 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 32 | 4 | NA |

| 148 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 20 | 0 | NA |

| 160 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 175 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 8 | 0 | NA |

| 209 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 1 | 1 | NA |

| 235 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 237 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 7 | 0 | NA |

| 249 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 296 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 326 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 337 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 363 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 420 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 472 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 484 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 647 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 649 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 650 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 655 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 656 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 658 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Ichneumonidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 442 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Megachilidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 673 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Megachilidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 92 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Mymaridae | 6 | 2 | NA |

| 252 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Mymaridae | 6 | 0 | NA |

| 659 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Mymaridae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 516 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Pelecinidae | 0 | 2 | NA |

| 65 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Pteromalidae | 13 | 0 | NA |

| 96 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Pteromalidae | 24 | 0 | NA |

| 212 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Pteromalidae | 8 | 7 | NA |

| 666 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Pteromalidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 667 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Pteromalidae | 0 | 13 | NA |

| 199 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Sphecidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 671 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Sphecidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 11 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Tenthredinidae | 12 | 0 | NA |

| 39 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Tenthredinidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 165 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Tenthredinidae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 176 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Tenthredinidae | 9 | 0 | NA |

| 642 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Tenthredinidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 651 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Tenthredinidae | 0 | 32 | NA |

| 98 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Trichogrammatidae | 10 | 0 | NA |

| 668 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Trichogrammatidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 191 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Vespidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 333 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Vespidae | 0 | 11 | NA |

| 404 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Vespidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 458 | Insecta | Hymenoptera | Vespidae | 1 | 0 | NA |

| 184 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Choreutidae | 20 | 0 | N |

| 692 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Choreutidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 129 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Crambidae | 19 | 0 | NA |

| 687 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Crambidae | 0 | 9 | NA |

| 74 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Geometridae | 8 | 0 | NA |

| 107 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Geometridae | 2 | 0 | E |

| 186 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Geometridae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 686 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Geometridae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 689 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Geometridae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 232 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Lycaenidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 690 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Lycaenidae | 0 | 3 | NA |

| 1 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | 24 | 0 | NA |

| 183 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | 11 | 0 | NA |

| 185 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 509 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 685 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 688 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 171 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Pieridae | 1 | 0 | E |

| 415 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Pieridae | 4 | 1 | N |

| 691 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Pieridae | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 382 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Pyralidae | 0 | 27 | NA |

| 217 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Tortricidae | 9 | 0 | I |

| 693 | Insecta | Lepidoptera | Tortricidae | 0 | 8 | NA |

| 444 | Insecta | Mantodea | Empusidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 240 | Insecta | Neuroptera | Hemerobiidae | 2 | 0 | NA |

| 255 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Acrididae | 3 | 1 | N |

| 267 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Acrididae | 0 | 42 | NA |

| 270 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Acrididae | 0 | 16 | NA |

| 493 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Acrididae | 0 | 5 | NA |

| 503 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Acrididae | 0 | 99 | NA |

| 511 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Acrididae | 0 | 10 | NA |

| 468 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Prophalangopsidae | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 63 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tetrigidae | 7 | 0 | NA |

| 64 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tetrigidae | 4 | 0 | NA |

| 682 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tetrigidae | 0 | 10 | NA |

| 202 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tettigoniidae | 9 | 0 | NA |

| 229 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tettigoniidae | 44 | 0 | NA |

| 309 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tettigoniidae | 0 | 6 | NA |

| 416 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tettigoniidae | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 683 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Tettigoniidae | 0 | 7 | NA |

| 82 | Insecta | Orthoptera | Trigonidiidae | 69 | 3 | I |

| 196 | Insecta | Phasmida | Phasmatidae | 1 | 0 | I |

| 94 | Insecta | Psocodea | Caeciliusidae | 48 | 3 | N |

| 120 | Insecta | Psocodea | Ectopsocidae | 21 | 0 | I |

| 206 | Insecta | Psocodea | Trichopsocidae | 7 | 0 | N |

| 200 | Insecta | Thysanoptera | Thripidae | 0 | 1 | N |

| Total | 7861 | 5654 |

References

- Graham, N.R.; Gruner, D.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Gillespie, R.G. Island Ecology and Evolution: Challenges in the Anthropocene. Environ. Conserv. 2017, 44, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Kreft, H.; Irl, S.D.H.; Norder, S.; Ah-Peng, C.; Borges, P.A.V.; Burns, K.C.; De Nascimento, L.; Meyer, J.-Y.; Montes, E.; et al. Scientists’ Warning—The Outstanding Biodiversity of Islands Is in Peril. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 31, e01847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylianakis, J.M.; Didham, R.K.; Bascompte, J.; Wardle, D.A. Global Change and Species Interactions in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heleno, R.H.; Ripple, W.J.; Traveset, A. Scientists’ Warning on Endangered Food Webs. Web Ecol. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, D.E.V.; Irl, S.D.H.; Seo, B.; Steinbauer, M.J.; Gillespie, R.; Triantis, K.A.; Fernández-Palacios, J.-M.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Impacts of Global Climate Change on the Floras of Oceanic Islands—Projections, Implications and Current Knowledge. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015, 17, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Heinen, R.; Armbrecht, I.; Basset, Y.; Baxter-Gilbert, J.H.; Bezemer, T.M.; Böhm, M.; Bommarco, R.; Borges, P.A.V.; Cardoso, P.; et al. International Scientists Formulate a Roadmap for Insect Conservation and Recovery. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueffer, C.; Kinney, K. What Is the Importance of Islands to Environmental Conservation? Environ. Conserv. 2017, 44, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.M.; Richards, L.A.; Wimp, G.M. Editorial: Arthropod Interactions and Responses to Disturbance in a Changing World. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, J.A.P.; Silva, L.; Garcia, P.V.; Weber, E.; Soares, A.O. Using Species Spectra to Evaluate Plant Community Conservation Value along a Gradient of Anthropogenic Disturbance. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 6221–6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, J.A.P.; Giordano, R.; Borges, P.A.V.; Garcia, P.V.; Soares, A.O. Distribution and Genetic Variability of Staphylinidae across a Gradient of Anthropogenically Influenced Insular Landscapes. Bull. Insectology 2016, 69, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, P.A.V.; Santos, A.M.C.; Elias, R.B.; Gabriel, R. The Azores Archipelago: Biodiversity Erosion and Conservation Biogeography. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 101–113. ISBN 978-0-12-816097-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hembry, D.H.; Bennett, G.; Bess, E.; Cooper, I.; Jordan, S.; Liebherr, J.; Magnacca, K.N.; Percy, D.M.; Polhemus, D.A.; Rubinoff, D.; et al. Insect Radiations on Islands: Biogeographic Pattern and Evolutionary Process in Hawaiian Insects. Q. Rev. Biol. 2021, 96, 247–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, J.; Borges, P.; Borges, I.; Pereira, E.; Santos, V.; Soares, A. Standardised Arthropod (Arthropoda) Inventory across Natural and Anthropogenic Impacted Habitats in the Azores Archipelago. BDJ 2021, 9, e62157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.B.; Donnelly, A. Carbon Sequestration in Temperate Grassland Ecosystems and the Influence of Management, Climate and Elevated CO2. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.; Nippert, J.; Briggs, J. Grassland Ecology. In Ecology and the Environment; Monson, R.K., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 389–423. ISBN 978-1-4614-7500-2. [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde, L.; Arbetman, M.; Arnan, X.; Eggleton, P.; Leal, I.R.; Lescano, M.N.; Saez, A.; Werenkraut, V.; Pirk, G.I. The Ecosystem Services Provided by Social Insects: Traits, Management Tools and Knowledge Gaps. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1418–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, L.C.; Allain, L.K.; Osland, M.J.; Pigott, E.; Reid, C.; Latiolais, N. A Comparison of Plant Communities in Restored, Old Field, and Remnant Coastal Prairies. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, G. Prairies and Grasslands: What’s in a Name? Fremontia 2011, 39, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, H.A.; Zavaleta, E. Ecosystems of California; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lark, T.J. Protecting Our Prairies: Research and Policy Actions for Conserving America’s Grasslands. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.D.; Smeins, F.E. Gradient Analysis of Remnant True and Upper Coastal Prairie Grasslands of North America. Can. J. Bot. 1988, 66, 2152–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameixa, O.M.C.C.; Soares, A.O.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Lillebø, A.I. Ecosystem Services Provided by the Little Things That Run the World. In Selected Studies in Biodiversity; Şen, B., Grillo, O., Eds.; InTech: Vienna, Austria, 2018; ISBN 978-1-78923-232-5. [Google Scholar]

- McGrady-Steed, J.; Morin, P.J. Biodiversity, Density Compensation, and the Dynamics of Populations and Functional Groups. Ecology 2000, 81, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.H.; Diamond, J.M.; Karr, J.R. Density Compensation in Island Faunas. Ecology 1972, 53, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.J. Density Compensation in Island Avifaunas. Oecologia 1980, 45, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novosolov, M.; Raia, P.; Meiri, S. The Island Syndrome in Lizards. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, S.R.; Brock, K.M.; Bednekoff, P.A.; Foufopoulos, J. More and Bigger Lizards Reside on Islands with More Resources. J. Zool. 2022, 319, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.; Yeates, G.W.; Wardle, D.A. Patterns of Invertebrate Density and Taxonomic Richness across Gradients of Area, Isolation, and Vegetation Diversity in a Lake-island System. Ecography 2009, 32, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, L.; Meyer, K.M.; Seifan, M. Trait-Based Modelling in Ecology: A Review of Two Decades of Research. Ecol. Model. 2019, 407, 108703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.O.; Honěk, A.; Martinkova, Z.; Skuhrovec, J.; Cardoso, P.; Borges, I. Harmonia Axyridis Failed to Establish in the Azores: The Role of Species Richness, Intraguild Interactions and Resource Availability. BioControl 2017, 62, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Borges, I.; Calado, H.; Borges, P. An Updated Checklist to the Biodiversity Data of Ladybeetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) of the Azores Archipelago (Portugal). BDJ 2021, 9, e77464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, B.H.; Simberloff, D.; Ricklefs, R.E.; Aguilée, R.; Condamine, F.L.; Gravel, D.; Morlon, H.; Mouquet, N.; Rosindell, J.; Casquet, J.; et al. Islands as Model Systems in Ecology and Evolution: Prospects Fifty Years after MacArthur-Wilson. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.J.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Matthews, T.J.; Borregaard, M.K.; Triantis, K.A. Island Biogeography: Taking the Long View of Nature’s Laboratories. Science 2017, 357, eaam8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, R.J.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Matthews, T.J. Island Biogeography: Geo-Environmental Dynamics, Ecology, Evolution, Human Impact, and Conservation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Heleno, R.; Lacerda, I.; Ramos, J.A.; Memmott, J. Evaluation of Restoration Effectiveness: Community Response to the Removal of Alien Plants. Ecol. Appl. 2010, 20, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.B.; Gil, A.; Silva, L.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Azevedo, E.B.; Reis, F. Natural Zonal Vegetation of the Azores Islands: Characterization and Potential Distribution. Phytocoenologia 2016, 46, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavão, D.C.; Jevšenak, J.; Engblom, J.; Borges Silva, L.; Elias, R.B.; Silva, L. Tree Growth-Climate Relationship in the Azorean Holly in a Temperate Humid Forest with Low Thermal Amplitude. Dendrochronologia 2023, 77, 126050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, M.I.P.; Santo, F.E.; Ramos, A.M.; Trigo, R.M. Trends and Correlations in Annual Extreme Precipitation Indices for Mainland Portugal, 1941–2007. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2015, 119, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Schmidt, L.; Santos, F.D.; Delicado, A. Climate Change Research and Policy in Portugal. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Fonseca, A.; Fragoso, M.; Santos, J.A. Recent and Future Changes of Precipitation Extremes in Mainland Portugal. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2019, 137, 1305–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.; Lamelas-Lopez, L.; Andrade, R.; Lhoumeau, S.; Vieira, V.; Soares, A.; Borges, I.; Boieiro, M.; Cardoso, P.; Crespo, L.C.; et al. An Updated Checklist of Azorean Arthropods (Arthropoda). BDJ 2022, 10, e97682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K.; Elsensohn, J.E. EstimateS Turns 20: Statistical Estimation of Species Richness and Shared Species from Samples, with Non-parametric Extrapolation. Ecography 2014, 37, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Chiu, C.-H.; Jost, L. Unifying Species Diversity, Phylogenetic Diversity, Functional Diversity, and Related Similarity and Differentiation Measures Through Hill Numbers. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 45, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.C.; Cardoso, P.; Gomes, P. Determining the Relative Roles of Species Replacement and Species Richness Differences in Generating Beta-diversity Patterns. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, C.S.; Trebitz, A.S.; Hoffman, J.C. Resolving Taxonomic Ambiguities: Effects on Rarity, Projected Richness, and Indices in Macroinvertebrate Datasets. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A. Measuring Biological Diversity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ricotta, C.; Feoli, E. Hill Numbers Everywhere. Does It Make Ecological Sense? Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L.; Lockwood, J.L. Biotic Homogenization: A Few Winners Replacing Many Losers in the next Mass Extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olden, J.D. Biotic Homogenization: A New Research Agenda for Conservation Biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 2027–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeten, L.; Vangansbeke, P.; Hermy, M.; Peterken, G.; Vanhuyse, K.; Verheyen, K. Distinguishing between Turnover and Nestedness in the Quantification of Biotic Homogenization. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, P.; Aranda, S.C.; Lobo, J.M.; Dinis, F.; Gaspar, C.; Borges, P.A.V. A Spatial Scale Assessment of Habitat Effects on Arthropod Communities of an Oceanic Island. Acta Oecologica 2009, 35, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.H. A Study of Summer Foliage Insect Communities in the Great Smoky Mountains. Ecol. Monogr. 1952, 22, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P. Interpreting the Replacement and Richness Difference Components of Beta Diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, M.; Rigal, F.; Ronquillo, C.; Borges, P.A.V.; Brito De Azevedo, E.; Santos, A.M.C. The Drivers of Plant Turnover Change across Spatial Scales in the Azores. Ecography 2024, 2024, e06697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soininen, J. Species Turnover along Abiotic and Biotic Gradients: Patterns in Space Equal Patterns in Time? BioScience 2010, 60, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, J.T.D.M.; Ouchi-Melo, L.S.; Crivellari, L.B.; De Oliveira, T.A.L.; Sawaya, R.J.; Duarte, L.D.S. Area and Distance from Mainland Affect in Different Ways Richness and Phylogenetic Diversity of Snakes in Atlantic Forest Coastal Islands. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 3909–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, H.S. The Mismeasure of Islands: Implications for Biogeographical Theory and the Conservation of Nature. J. Biogeogr. 2004, 31, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.; Reut, M.; da Ponte, N.B.; Soares, A.O.; Marcelino, J.; Rego, C.; Cardoso, P. New Records of Exotic Spiders and Insects to the Azores, and New Data on Recently Introduced Species. Arquipélago Life Mar. Sci. 2013, 30, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, P.; Lamelas-Lopez, L.; Stüben, P.; Ros-Prieto, A.; Gabriel, R.; Boieiro, M.; Tsafack, N.; Ferreira, M.T. SLAM Project—Long Term Ecological Study of the Impacts of Climate Change in the Natural Forest of Azores: II—A Survey of Exotic Arthropods in Disturbed Forest Habitats. BDJ 2022, 10, e81410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock, M.J.W.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Cannon, R.J.C.; Gerard, P.J.; Gillespie, D.; Jiménez, J.J.; Lavelle, P.M.; Raina, S.K. The Positive Contribution of Invertebrates to Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. CABI Rev. 2012, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, N.S.; Ehrlich, P.R. Conservation Biology for All; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-19-955423-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, C.E.; Aslan, A.; Croll, D.; Tershy, B.; Zavaleta, E. Building Taxon Substitution Guidelines on a Biological Control Foundation. Restor. Ecol. 2014, 22, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleno, R.H.; Mendes, F.; Coelho, A.P.; Ramos, J.A.; Palmeirim, J.M.; Rainho, A.; De Lima, R.F. The Upsizing of the São Tomé Seed Dispersal Network by Introduced Animals. Oikos 2022, 2022, oik.08279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, J.; Whittaker, R.J.; Borges, P.A.V.; Fernández-Palacios, J.M.; Ah-Peng, C.; Araújo, M.B.; Ávila, S.P.; Cardoso, P.; Cornuault, J.; De Boer, E.J.; et al. A Roadmap for Island Biology: 50 Fundamental Questions after 50 Years of the Theory of Island Biogeography. J. Biogeogr. 2017, 44, 963–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, J.C.; Turner, P.L.; Phillipson, C.N.; Seltmann, K.C. Local Grassland Restoration Affects Insect Communities. Ecol. Entomol. 2019, 44, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, A.N.; Emery, S.M. Grassland Restorations Improve Pollinator Communities: A Meta-Analysis. J. Insect Conserv. 2020, 24, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class | Order | Azores | Mainland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arachnida | 22 | 55 | |

| Araneae | 21 | 54 | |

| Opiliones | 1 | 1 | |

| Diplopoda | 1 | ||

| Julida | 1 | ||

| Insecta | 187 | 336 | |

| Coleoptera | 26 | 109 | |

| Diptera | 42 | 42 | |

| Hemiptera | 44 | 73 | |

| Hymenoptera | 51 | 86 | |

| Lepidoptera | 12 | 12 | |

| Mantodea | 1 | ||

| Neuroptera | 1 | ||

| Orthoptera | 7 | 11 | |

| Phasmida | 1 | ||

| Psocodea | 3 | 1 | |

| Thysanoptera | 1 | ||

| Total | 210 | 391 |

| Class | Order | Family | Species | Total Abundance Azores | Total Abundance Mainland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arachnida | Araneae | Araneidae | Mangora acalypha (Walckenaer, 1802) | 16 | 117 |

| Neoscona crucifera (Lucas, 1838) | 8 | 1 | |||

| Zygiella x-notata (Clerck, 1757) | 42 | 66 | |||

| Linyphiidae | Oedothorax fuscus (Blackwall, 1834) | 11 | 4 | ||

| Prinerigone vagans (Audouin, 1826) | 52 | 15 | |||

| Salticidae | Chalcoscirtus infimus (Simon, 1868) | 73 | 13 | ||

| Macaroeris diligens (Blackwall, 1867) | 16 | 6 | |||

| Salticus mutabilis Lucas, 1846 | 31 | 28 | |||

| Synageles venator (Lucas, 1836) | 61 | 7 | |||

| Thomisidae | Xysticus nubilus Simon, 1875 | 90 | 97 | ||

| Insecta | Coleoptera | Apionidae | Aspidapion radiolus (Marsham, 1802) | 72 | 3 |

| Chrysomelidae | Psylliodes marcida (Illiger, 1807) | 11 | 49 | ||

| Coccinellidae | Rhyzobius litura (Fabricius, 1787) | 38 | 5 | ||

| Scymnus interruptus (Goeze, 1777) | 129 | 2 | |||

| Scymnus suturalis Thunberg, 1795 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Curculionidae | Mecinus pascuorum (Gyllenhal, 1813) | 286 | 18 | ||

| Nitidulidae | Brassicogethes aeneus (Fabricius, 1775) | 54 | 8 | ||

| Phalacridae | Stilbus testaceus (Panzer, 1797) | 14 | 10 | ||

| Staphylinidae | Tachyporus chrysomelinus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Diptera | Agromyzidae | Chromatomyia nigra (Meigen, 1830) | 10 | 1 | |

| Calliphoridae | Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) | 16 | 3 | ||

| Chloropidae | Thaumatomyia notata (Meigen, 1830) | 32 | 35 | ||

| Lonchopteridae | Lonchoptera bifurcata (Fallén, 1810) | 67 | 69 | ||

| Muscidae | Coenosia humilis Meigen, 1826 | 65 | 8 | ||

| Musca osiris Wiedemann, 1830 | 70 | 6 | |||

| Stomoxys calcitrans (Linnaeus, 1758) | 123 | 71 | |||

| Opomyzidae | Geomyza tripunctata (Fallén, 1823) | 4 | 3 | ||

| Rhinophoridae | Melanophora roralis (Linnaeus, 1758) | 82 | 15 | ||

| Syrphidae | Eristalis tenax (Linnaeus, 1758) | 4 | 3 | ||

| Eupeodes corollae (Fabricius, 1794) | 15 | 7 | |||

| Sphaerophoria scripta (Linnaeus, 1758) | 34 | 12 | |||

| Tephritidae | Dioxyna sororcula (Wiedemann, 1830) | 220 | 1 | ||

| Hemiptera | Anthocoridae | Orius laevigatus laevigatus (Fieber, 1860) | 44 | 3 | |

| Aphididae | Aphis fabae Scopoli, 1763 | 58 | 2 | ||

| Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe, 1841 | 42 | 2 | |||

| Melanaphis donacis (Passerini, 1862) | 257 | 48 | |||

| Myzus persicae (Sulzer, 1776) | 127 | 45 | |||

| Therioaphis trifolii (Monell, 1882) | 19 | 10 | |||

| Aphrophoridae | Philaenus spumarius (Linnaeus, 1758) | 285 | 241 | ||

| Cicadellidae | Macrosteles sexnotatus (Fallen, 1806) | 301 | 14 | ||

| Delphacidae | Megamelodes quadrimaculatus (Signoret, 1865) | 44 | 3 | ||

| Sogatella nigeriensis (Muir, 1920) | 252 | 45 | |||

| Lygaeidae | Kleidocerys ericae (Horváth, 1909) | 49 | 6 | ||

| Nysius ericae ericae (Blackwall, 1867) | 14 | 15 | |||

| Miridae | Taylorilygus apicalis (Fieber, 1861) | 433 | 26 | ||

| Nabidae | Nabis capsiformis Germar, 1838 | 180 | 3 | ||

| Pentatomidae | Nezara viridula (Linnaeus, 1758) | 53 | 13 | ||

| Psyllidae | Acizzia uncatoides (Ferris & Klyver, 1932) | 15 | 21 | ||

| Rhyparochromidae | Beosus maritimus (Scopoli, 1763) | 1 | 9 | ||

| Saldidae | Saldula palustris (Douglas, 1874) | 4 | 1 | ||

| Hymenoptera | Aphelinidae | Encarsia formosa Gahan, 1924 | 9 | 2 | |

| Apidae | Apis mellifera Linnaeus, 1758 | 19 | 6 | ||

| Bombus terrestris (Linnaeus, 1758) | 16 | 3 | |||

| Encyrtidae | Pseudaphycus maculipennis Mercet, 1923 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Eulophidae | Baryscapus galactopus (Ratzeburg, 1844) | 69 | 86 | ||

| Diglyphus isaea (Walker, 1838) | 6 | 4 | |||

| Formicidae | Hypoponera eduardi (Forel, 1894) | 5 | 5 | ||

| Lasius grandis Forel, 1909 | 593 | 6 | |||

| Tetramorium caespitum (Linnaeus, 1758) | 20 | 4 | |||

| Ichneumonidae | Aritranis director (Thumberg, 1822) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Diplazon laetatorius (Fabricius, 1781) | 32 | 4 | |||

| Mymaridae | Litus cynipseus Haliday, 1833 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Pteromalidae | Pteromalus puparum (Linnaeus, 1758) | 8 | 7 | ||

| Lepidoptera | Pieridae | Colias croceus (Fourcroy, 1785) | 4 | 1 | |

| Orthoptera | Acrididae | Locusta migratoria (Linnaeus, 1758) | 3 | 1 | |

| Trigonidiidae | Trigonidium cicindeloides Rambur, 1838 | 69 | 3 | ||

| Psocodea | Caeciliusidae | Valenzuela flavidus (Stephens, 1836) | 48 | 3 | |

| Total | 4848 | 1332 |

| Azores | Mainland | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 7861 | 5654 |

| S | 210 | 392 |

| Chao 1 | 245.06 | 464.18 |

| Jackknife1 | 252.16 | 491.56 |

| Completeness Chao1 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Completeness Jackknife1 | 0.83 | 0.80 |

| Singletons | 34 | 82 |

| Doubletons | 15 | 45 |

| Uniques | 43 | 101 |

| Duplicates | 45 | 79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calado, H.R.M.G.; Borges, P.A.V.; Heleno, R.; Soares, A.O. A Comparative Analysis of Island vs. Mainland Arthropod Communities in Coastal Grasslands Belonging to Two Distinct Regions: São Miguel Island (Azores) and Mainland Portugal. Diversity 2024, 16, 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16100624

Calado HRMG, Borges PAV, Heleno R, Soares AO. A Comparative Analysis of Island vs. Mainland Arthropod Communities in Coastal Grasslands Belonging to Two Distinct Regions: São Miguel Island (Azores) and Mainland Portugal. Diversity. 2024; 16(10):624. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16100624

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalado, Hugo Renato M. G., Paulo A. V. Borges, Ruben Heleno, and António O. Soares. 2024. "A Comparative Analysis of Island vs. Mainland Arthropod Communities in Coastal Grasslands Belonging to Two Distinct Regions: São Miguel Island (Azores) and Mainland Portugal" Diversity 16, no. 10: 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16100624

APA StyleCalado, H. R. M. G., Borges, P. A. V., Heleno, R., & Soares, A. O. (2024). A Comparative Analysis of Island vs. Mainland Arthropod Communities in Coastal Grasslands Belonging to Two Distinct Regions: São Miguel Island (Azores) and Mainland Portugal. Diversity, 16(10), 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16100624