Abstract

Located in Lestelas-Balaguères massif, central northern Pyrenees, France, the Baget catchment covers 13.25 km2 and is highly karstified: so far, more than 80 caves have been recorded. The main outlet of the system, the exsurgence de Las Hountas, has an average flow of 550 L/s. Downstream, it is connected with the hyporheic of the Lachein stream. The Baget system, formed by both the karstic system and the hyporheic, has been intensively investigated by cave biologists and is known to be a hotspot for subterranean biodiversity. The synthesis provided here lists no less than 17 troglobionts and 40 stygobionts, with 3 single site endemics, making the Baget system the richest subterranean hotspot in the Pyrenees. This is notably due to the diversity of subterranean habitats and to the comprehensive knowledge of the stygofauna, likely unmatched at the European scale. Considering the significant speleological findings of the last 15 years that have not been yet biologically investigated, we can expect new discoveries, especially for the troglofauna.

1. Introduction

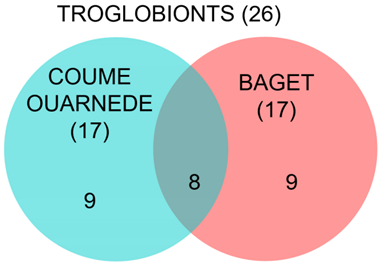

The Pyrenean range, especially on the central and western area of its northern slope, is known to be one of the world hotspots for subterranean fauna [1]. Within this area, three sites stand out for their high diversity: the hyporheic of the Nert, the Coume Ouarnède system [2] and the subterranean Baget system, including both karstic and hyporheic habitats (Figure 1). The latter, which is still being explored by cavers, has been extensively studied and sampled over more than 50 years by biologists, benefiting from the close proximity of the CNRS laboratory in Moulis, and has become a global reference for the subterranean aquatic fauna of karst and hyporheic environments.

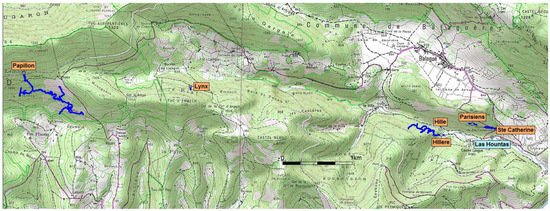

Figure 1.

Location of the Baget system, central Pyrenees, South France.

In this study, based on bibliographic data and unpublished observations, we gathered the most comprehensive list of troglobionts and stygobionts for the Baget system, considering both the karst environment and the hyporheic environment. The aim of this article is to present the general features of this system, incorporating some unpublished speleological and hydrological data, and to provide an overview of its fauna, put in its ecological and biogeographical contexts.

2. Study Site

2.1. The Lestelas-Balaguères Massif

The Lestelas-Balaguères massif straddles the departments of Ariège (13 municipalities) and Haute-Garonne (4 municipalities). It covers an area of around 88 km2. It is heavily karstified and attracted the interest of cavers very early on. The inventories, initiated by Georges Jauzion, taken over by Daniel Quettier and amended by the caving committees of Ariège and Haute-Garonne with the support of local caving groups, list more than 500 caves [3]; D. Quettier, pers com.

In this area, the Mesozoic series that covers the crystalline massif is represented by terrain ranging from the Triassic to the Turonian. The Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous are the two predominant carbonate formations, and karstification is most marked in the Jurassic-Neocomian and Upper Aptian with Urgonian facies [4].

The Lestelas-Balaguères massif is drained by several karstic systems. The most important are the Peillot system; the Bethmale/Hount Heredo system; the Pas du Loup/Teillèdes or Francazal system; the Belle/Cassagnous or underground Hider system; the Coume Ferrat/Aliou or Paloumé system; and the Papillon/Las Hountas or underground Baget system.

The Peillot system, located on the edge of the massif near the village of Cazavet, is apart as it is developed in sandstone marl from the Albian. The three subterranean systems of Hider, Paloumé and Baget share many morphological similarities. Their upper entrances are at similar altitudes (Belle, 1162 m; Bagagès, 1172 m; Papillon, 1150 m), with their respective exsurgences at 505 m (Cassagnous), 441 m (Aliou) and 493 m (Las Hountas). The upper entrances provide access to a series of shafts leading to an active stream with a low gradient. The gradient increases significantly in all three cases shortly before reaching the flooded zone, which is of wide extension.

For the Hider subterranean system, the junction between the upper entrance and the resurgence has been completed (exploration of Gouffre Belle by the Spéléo-Club de l’Epia and of the flooded zone by cave divers G. Tixier and F. Bréhier), [5,6]. For Paloumé and Baget systems, a large gap remains. In all these systems, exploration is still in progress by local caving groups [3,7,8,9].

2.2. The Subterranean Baget System

The Baget catchment is located in the southern part of the Lestelas-Balaguères massif in Ariège. It adjoins the Arbas massif to the West at the level of the ridges passing through the Pic de Cornudère and the Tuc de Pissarelle. According to the limits proposed by A. Mangin [4,10,11,12], it extends from West to East over ten kilometers long with a fairly irregular width varying from 1 to 2 km. It is drained by the exsurgence of Las Hountas, located at its eastern end. The catchment covers 13.25 km2, of which 4 km2—i.e., around 30%—are of impermeable non-calcareous terrain.

It is made up of a homogenous structure of crystalline Mesozoic limestone [13]. The Alas fault forms its northern boundary. To the South, the limestone disappears beneath the clay-gravel formations of the Albo-Cenomanian. The western limit, in continuity with the Arbas massif, is more difficult to define, with metamorphosed limestones interspersed with dolomites. It is supposed to extend to the Col de la Croix de Guéret. Its surface area is mostly covered by forests and pastures. There is very little anthropic activity. Its average altitude is 955 m, ranging from 493 m (altitude of the Las Hountas resurgence) to 1417 m (altitude of the Tuc de Graué). Annual precipitation is around 1700 mm, the climate is oceanic with high water level ranging from November to April. The average temperature is 12.3 °C [10,11,12].

Not under threat and not under formal protection measures, the biological richness of the massif is nevertheless remarkable, and has been labeled as Zone Naturelle d’Intérêt Écologique, Faunistique et Floristique (ZNIEFF) Soulane de Balaguères au Char de Liqué (national ID: 730012100) and is included in a Natura 2000 site (Chars de Moulis et de Liqué, grotte d’Aubert, Soulane de Balaguères et de Sainte-Catherine, granges des vallées de Sour et d’Astien, national ID FR7300836).

The main outlet of the system is the perennial exsurgence de Las Hountas, made up of around ten impenetrable griffons, at an altitude of 493 m. Its average flow is 550 L/s, with a minimum of 50 L/s and floods approaching 11,000 L/s [10,11,12]. It gives rise to the perennial Lachein stream, which flows after 1.5 km into the Lez River at the village of Alas. At Saint-Girons, the Lez meets the Salat River, a tributary of the Garonne. Collections and studies of the hyporheic environment were carried out approximately halfway between the exsurgence of las Hountas and the confluence with the Lez, on a shallow slope.

A second exsurgence is located in the village of Alas, at an altitude of 483 m. It might be fed partly by sinkholes from the Lachein, and partly by seepage into the metamorphosed limestone on the right bank downstream of Las Hountas. The relationships between these two supposed exsurgences and systems are not clearly defined. Upstream of the exsurgence de Las Hountas, the stream only flows during episodes of rain. The caves Moulo del Jaur, Puits de la Hillère (Hillère sinkhole), Perte de la Hille (Hille sinkhole) and Perte de la Peyrère (Peyrère sinkhole) then function in turn as exsurgences, depending on the intensity of the flows.

2.3. Speleological Data

The Baget catchment area is largely karstified, and around 80 caves have been recorded by cavers [3], D. Quettier, pers com.

At present, four of these caves provide access to the system’s perennial drain. These are from downstream to upstream Puits de la Hillère, Perte de la Hille, Gouffre de la Peyrère and Gouffre du Papillon.

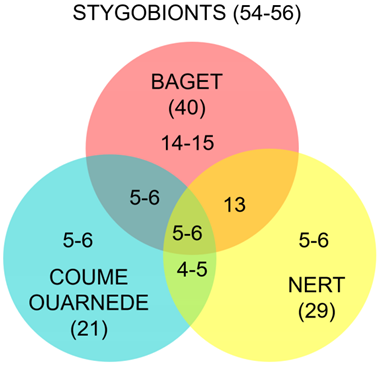

Puits de la Hillère, Perte de la Hille and the gouffre de la Peyrère are located in the downstream part of the system, approximately 1 km from the outlet. Recent explorations by cave diving have allowed connecting these three caves together [6]. They form a network of passages more than 1500 m long, including 800 m of flooded conduits (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of the lower part of Baget karstic system, including Gouffre de la Peyrère, Perte de la Hille and Puits de la Hillère, connected by cave diving.

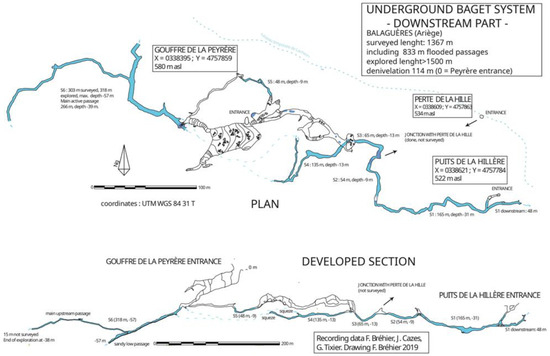

The Gouffre du Papillon, discovered in 1964 by Émile Bugat, is located more than 6 km from the outlet, making it the most upstream known section of the system. Recent speleological explorations by the Groupe Spéléologique du Couserans in 2007 permitted to extend its length to more than 6 km and its depth to more than 600 m (−604 m), and to reach the main drain. Upstream of the main drain, explorations have been temporarily stopped in sump 2, at a depth of −25 m, on an unstable sand slope. Downstream, at −563 m, a sump was dived to a depth of −43 m by Franck Bréhier. The passage continues with the same large dimensions and further explorations are needed. Between the far downstream end of the Gouffre du Papillon and the far upstream end of the Gouffre de la Peyrère, a large void 4.6 km long in a straight line remains (Figure 3). The vast majority of the network has yet to be discovered, but at present no other caves are known in the supposed route of the collector that could potentially join it. In addition, the small difference in level between the sumps in the Papillon and Peyrère suggests that a large part of the active system flows through a flooded zone, which greatly complicates exploration.

Figure 3.

Relative positions of the main caves of the Baget system (see Figure 1 for location), from Gouffre du Papillon, upstream, to the exsurgence de Las Hountas. From CartoExplorer 3.

2.4. Hydrological Features

According to the model proposed by A. Mangin [10,11,12], the Baget system consists of a highly transmissive but low-capacity drain running beneath the Lachein valley talweg. Gouffre de la Peyrère, Puits de la Hillère and Grotte de Saint-Catherine, which are caves giving access to the flooded karst, would be ancillary systems to the drain, with low transmissivity but high capacitance. In this way, water reserves would be built up in large reservoirs that are not directly interconnected. This is the model that has been adopted to date [14]. In fact, recent underground diving explorations have shown that Puits de la Hillère and Gouffre de la Peyrère are directly linked and that the drain passes through both caves (Figure 2). This means that the drain is not located directly beneath the talweg, but rather, at least in the downstream part of the system, runs along its right bank. Perte de la Hille, supposed to be directly on the drain, is offset from it, and is connected to it by a narrow gallery inactive at low water. We can assume that Grotte de Sainte-Catherine, located on the left bank and further downstream, at the level of Las Hountas outlet, is disconnected from the drain, although it is not yet possible to confirm this.

2.5. The Baget System in Terms of Subterranean Habitats

Despite its relatively small size, the subterranean Baget system presents a great diversity of habitats. For terrestrial fauna, the vast vertical entrances of Gouffre de la Peyrère and Grotte de Sainte-Catherine offer a scree area rich in organic matter, favorable to endogean species (Figure 4, top). The deposits of bat guano in Grotte de Sainte-Catherine favors the presence of guanophilic fauna. The variety of underground landscapes encountered through the numerous caves of the system and the kilometers of passages of Gouffre du Papillon, still untouched by any biospeleological surveys (fossil galleries, large wells, calcite flows, clay deposits, etc.) are all potential habitats.

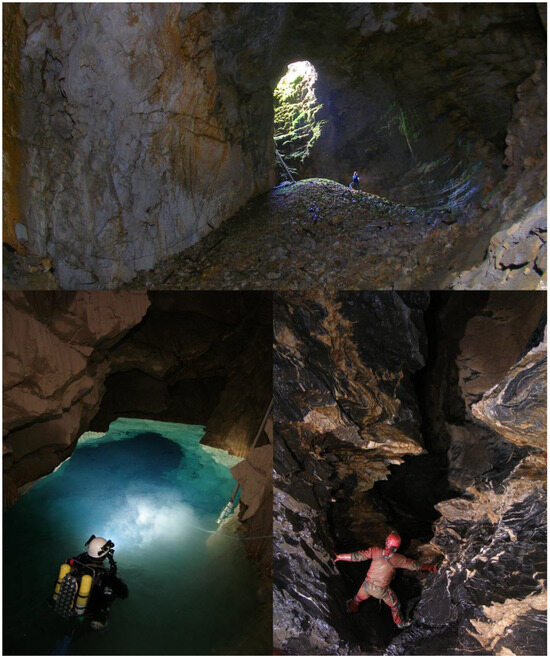

Figure 4.

Different aspects of Baget karstic system. (Top): the main chamber of Gouffre de la Peyrère. (Bottom left): the main sump of Gouffre de la Peyrère. (Bottom right): caving exploration in Gouffre du Papillon. Photos F. Bréhier.

For aquatic fauna, Grotte de Sainte-Catherine offers access to the vertical flows of the epikarst and to the fissural environment which was instrumented by the Moulis Laboratory. Gours, basins, and streams in the vadose zone are found in large numbers at Grotte de Sainte-Catherine, at Gouffre de la Peyrère and especially at Gouffre du Papillon. Flooded karst has been widely studied by filtration of the various perennial or temporary outlets of the system [15,16] or by pumping at Gouffre de la Peyrère [17]. If recent speleological discoveries have shown that the compartments of Exsurgence de Las Hountas, Puits de la Hillère and Gouffre de la Peyrère are not disconnected from each other, the fact remains that they shelter distinct biocenoses and that the flooded karst should not be considered as a single habitat at a system scale. Finally, the underflow of the Lachein downstream of Exsurgence de Las Hountas also offers a great diversity of habitats for hyporheic fauna [18].

2.6. History of Biological Research on the Subterranean Baget System

In 1948, R. Jeannel of the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Paris) convinced the CNRS (National Center for Scientific Research) to set up an underground laboratory in the commune of Moulis, a few kilometers from Le Baget [19,20]. The Moulis site was chosen, among other criteria, for the rich underground fauna of the area, already well documented by Jeannel [21]. The aim was to carry out breeding of cave animals in a natural environment as well as to develop multidisciplinary studies of the subterranean environment including geology, hydrogeology and biology.

The Baget catchment was chosen as an experimental site for several reasons: its immediate proximity to the Moulis Laboratory and ease of access, its relatively small size and the richness of its fauna. It has been the subject of hydrological, climatic and hydrochemical monitoring for almost 50 years. Numerous interdisciplinary studies including geomorphology [22], population monitoring [23], climatology/population relationships [24,25], and hydrogeology [26], were carried out on this site and made it a national reference.

The site is particularly suited to an experimental ecological approach of the structures of communities of underground species. From 1967, R. Rouch carried out an in-depth study and sampled extensively the aquatic fauna of the Baget catchment. He began to sample the hyporheic fauna of Lachein in 1967 [27] and, from 1988, he led a comprehensive study of ground water communities linked to a karst aquifer [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. His work has become a World reference.

Concerning terrestrial fauna, most of the published investigation were done at Grotte de Sainte-Catherine and concerned Coleoptera (see Section 4.1.7).

3. Material and Methods

The data presented in this article come from primary literature compilation as well as personal data.

Almost all of the investigations and publications on aquatic fauna are due to R. Rouch. Collections in the interstitial environment of the Lachein underflow were made by Bou-Rouch pumping, filtered through net with 100 µm mesh [18]. For the karstic stygobiotic fauna, the samples came from filtering the main outlet of Las Hountas; the temporary outlets of Moulo de Jaur, Puits de la Hillère and Perte de la Hille, during episodes of flooding. Data from the gouffre de la Peyrère come mainly from the pumping operation led by A. Mangin in 1991 [17]. Crustaceans were studied by Rouch, and identified by different specialists. Data on Oligochaeta, due to Route et al. [37], come from Rouch’s sampling [36,37].

While aquatic sampling was made following strict protocols in the long term, terrestrial sampling was rather opportunistic. Data on terrestrial fauna are more scarce and compiled from various publications. They concern Gouffre de Tussau, Gouffre de la Peyrère, Grotte de Sainte-Catherine and Gouffre du Lynx. For our own investigations, we sampled by sight, by baiting and using pitfalls.

The names and validity of the species were checked using the taxonomic referential TaxRef of INPN (MNHN & OFB [Ed]. 2003–2023) [38]. Species ecological status were inferred from the taxonomic literature, particularly from R. Rouch publications. It covers all described species on our list. Only obligate subterranean species (stygobionts and troglobionts), and facultative subterranean species (stygophiles and eutroglophiles) have been considered here. The latter are often numerically dominant in subterranean communities and have been included here for this reason.

4. Results

We will separately consider aquatic and terrestrial subterranean fauna. For each, we will list in four tables (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, respectively) both the obligate and facultative subterranean species. Most relevant stygobionts and troglobionts will be commented on individually.

Table 1.

Stygobiotic species of the Baget system. K: Karst; HR: Hyporheic; Species in bold: single site endemics.

Table 2.

Stygophilic species of the Baget system.

Table 3.

Troglobiotic species of the Baget system. Species in bold: single site endemism.

Table 4.

Troglophilic species of the Baget system.

4.1. Aquatic Fauna

4.1.1. Oligochaeta

Delaya leruthi (Hrabe, 1958) is present in Grotte de Sainte-Catherine. This large species is known from central Pyrenees and especially common in caves of l’Estelas-Balaguères massif [39].

Cookidrilus ruffoi Giani, Martinez-Ansemill & Sambugar, 2004 is an endemic species of Lachein, whereas Cookidrilus speluncaeus Rodriguez & Giani, 1987 is known as well from grotte de Labouiche, some 50 km from Lachein [37].

Spiridion phreaticola (Juget, 1987) is a stygobiont with a larger distribution. It has been mentioned in the interstitial waters of the Rhône, the Neste d’Aure and the Dordogne, as well as in the underground river of Grotte de Labouiche [37].

4.1.2. Gastropoda

Bertrand (unpublished inf., 2002) mentions Moitessieria simoniana (Saint-Simon, 1848) and Neohoratia globulina Paladilhe, 1866), now considered as a synonym of Islamia moquiniana (Dupuy, 1851). Moitessieria simoniana has a distribution covering the Pyrenees and the South of the Massif Central. It is common in Ariège. Islamia moquiniana, also common in Ariège, has a wide distribution in the southern half of France. These species are present both in the hyporheic environment and in the karst [39].

4.1.3. Copepoda

Crustacea are considered as the most diversified stygobiotic taxon in Europe, and represent 70% of the groundwater species richness [40].

Copepods constitute the dominant contingent of the subterranean aquatic fauna of the Baget. Taking into account both the hyporheic environment and the flooded karst, a total of 33 species have been documented, including 14 species of Cyclopoida Cyclopidae and 19 species of Harpacticoida distributed into Ameiridae (3), Canthocamptidae (13) and Parastenocarididae (3). This rich community includes many stygobionts: 10 cyclopid and 12 harpacticoid species, to which are added a number of stygophilous or stygoxenous forms that also occupy subterranean habitats to a greater or lesser extent.

For the hyporheic environment of the Lachein alone, over an area of 75 m2, Rouch counted 22 species of harpacticoids including 10 stygobionts and 14 species of cyclopids including 7 stygobionts [41,42]. Although the spatial and physico-chemical heterogeneity of this environment leads to a heterogeneous distribution of the diversity, it remains stable over time and in its structure.

Studies of flooded karst by the filtration of outlets over long periods show a high degree of homogeneity of the populations in time and space, with each outlet having a taxonomic composition that is constant but original and different from the other outfalls [43,44,45,46,47,48]. Filtration of the exsurgence de Las Hountas yielded 11 species of cyclopids, including 4 stygobionts, and 21 species of harpacticids, including 8 stygobionts [15].

In addition to the large number of stygobionts, the copepods of the Baget system are characterized by a great number of taxa of higher order and a great number of endemic species.

Among the Cyclopidae, the majority are stygobionts. Several species of the genera Acanthocyclops and Diacyclops, common in underground environments, are found such as Acanthocyclops sensitivus (Graeter & Chappuis, 1914), Diacyclops belgicus Kiefer, 1936, Diacyclops clandestinus (Kiefer, 1926). Although we would rather consider Diacyclops languidoides (Lilljeborg, 1901) as a stygophilic species, we have listed it as a stygobiotic as it is often so-cited [2,40]. It is above all the genera Graeteriella and Speocyclops, typical of these environments and all endemic either to the Pyrenees or to underground habitats in France, that are the best represented, with Graeteriella (Grateriella) rouchi Lescher-Moutoué, 1968, Speocyclops. anomalus Chappuis & Kiefer, 1952, S. kieferi Lescher-Moutoué, 1968, S. racovitzai boscensis Kiefer 1954 and S. racovitzai liquensis Chappuis & Kiefer, 1952. Among the Harpacticoida, three families are represented, well known from underground environments: Ameiridae, Canthocamptidae and Parastenocarididae. The family Ameiridae is represented by three stygobionts, including two endemic ones: Nitocrella delayi Rouch, 1970 (microendemic in Ariège) and N. gracilis Chappuis, 1955, (endemic in Ariège and Haute-Garonne; the third one, Parapseudoleptomesochra subterranea subterranea (Chappuis, 1928) is known from many caves, hyporheic habitats and springs. The family Canthocamptidae, generally very common in such habitats, comprises six stygobitic representatives belonging to four genera: Antrocamptus with two species endemic in Ariège, A. catherinae Chappuis & Rouch, 1960 (cave) and A. chappuisi Rouch, 1970, the latter collected through filtering, Ceuthonectes with C. gallicus Chappuis, 1928 considered as the most abundant species in subterranean waters of Pyrenees, Elaphoidella with the microendemic E. coiffaiti Chappuis & Kiefer, 1952 preferring muddy bottoms and E. bouilloni Rouch, 1965, which prefers sites with fine sand; and Moraria with the endemic M. (M.) catalana Chappuis & Kiefer, 1952. Among the stygophile canthocamptid, Bryocamptus is the most diverse with three species: B. (Echinocamptus) echinatus (Mrazek, 1893), a cold-water stenotherm species with a wide palearctic distribution, B. (Rheocamptus) typhlops (Mrazek, 1893), spread across Europe, inhabiting fountains, springs and subterranean waters and the common B. (R.) zschokkei (Schmeil, 1893) living also in cold waters of mosses, springs of central Europe, Eurasia and North America.

Finally the large family Parastenocarididae, composed of more than 300 species highly specialized for life in groundwater habitats thanks to their physical ability to move in small spaces with their cylindrical and slender body and their small size (less than a millimeter), is represented in the Baget system by three species, all endemic: Parastenocaris dianae Chappuis, 1955, Parastenocaris vandeli Rouch, 1988 and Proserpinicaris mangini (Rouch, 1992). It is likely that other representatives of this family will be collected in future investigations.

Among Copepoda, more than 40% of the species reported to date are endemics, illustrating the biological richness of the Baget system.

4.1.4. Ostracoda

The class Ostracoda occurs in almost all aquatic and even some terrestrial habitats. Several lineages have subterranean representatives or are exclusively living in groundwaters. The subterranean ostracod fauna is, however, still poorly known.

One of the most diverse family in freshwaters is the large family Candonidae (29% of all species in non-marine habitats [49]). In the Baget system, this family is represented by four species of the genus Pseudocandona, three of which undescribed [18]. Two undescribed species are found in the karstic system, whereas Pseudocandona rouchi Danielopol, 1973 and the third undescribed species occur in the hyporheic environment of Lachein.

Another species, Fabaeformiscandona breuili (Paris, 1920), previously often designated as Candona hertzogi Klie, 1937 was collected in the hyporheic of the Lachein. Considered as a stygobiont by Rouch, it is actually a styglophile.

4.1.5. Bathynellacea (Syncarida)

The genus Vandelibathynella is monospecific, represented by Vandelibathynella vandeli [50]. When Delamare and Chappuis described this species from Grotte de Font-Sainte, in Ariege, in 1954 under the genus Bathynella, they noted its special position within the group. It was later reported as being in the Baget karstic system [51] and from the hyporheic of Lachein [18]. Since then, it has only been found in two other localities, both in Ariège: Grotte de Passarolles [52], and in the hyporheic environment of the Nert stream [53]. Within the hyporheic environment of Lachein, it is found exclusively in areas of low permeability and low concentration in oxygen, which are also the least populated areas.

4.1.6. Amphipoda

Three species of amphipods inhabit the underground waters of the Baget system. One is a species of the genus Niphargus. It has been attributed to Niphargus kochianus Bate, 1859, but is actually a species of the kochianus group [54]. Its taxonomic status remains to be clarified. This species group is widely distributed throughout western Europe. Small for a Niphargus (5 to 6 mm), it prefers interstitial environments.

The other amphipods, which are also typical of interstitial environments, have a more restricted distribution.

Salentinella petiti Coineau, 1968 is found in North-West Spain and South-West France (Dordogne, Tarn, Tarn et Garonne, Lot, Pyrénées Atlantiques, Hautes-Pyrénées, Haute-Garonne and Ariège). Like the bathynellacea Vandelibathynella vandeli, it is typical of the least drained and the most oxygen-poor areas of the hyporheic environment.

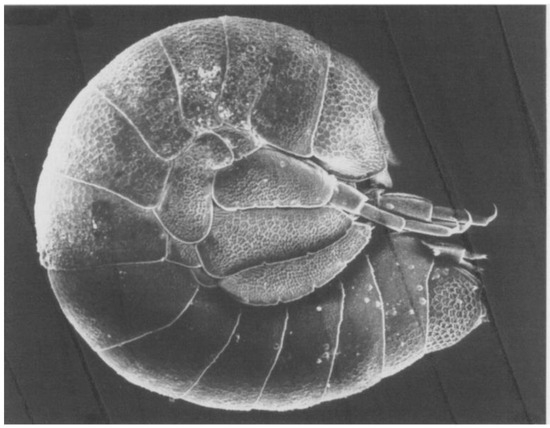

Parasalentinella rouchi Bou,1971 is a small amphipod, less than 2 mm long with volvation abilities. Its distribution area is limited to the interstitial environments in the Pyrenees of Ariège and Haute-Garonne [55] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Parasalentinella rouchi. Photo C. Bou. From Danielopol, Rouch & Bou, 1999.

4.1.7. Ingolfiellida

This peracarid order is represented in Baget by Ingolfiella thibaudi Coineau, 1968, a small anophtalmous Ingolfiellida, about 2 mm long and very elongated. It has a regional distribution in southern France covering Ariège, Hautes-Pyrénées, Tarn, Ardèche, Gard and Bouches-du-Rhône.

4.1.8. Isopoda

Two species have been recorded from the Baget: Microcharon ariegensis (Coineau, Boutin & Artheau, 2013) and Stenasellus virei Dollfus, 1897. Microcharon is a microparasellid isopod genus found in interstitial groundwater, river underflows and marine interstitial. The species has a worldwide although highly fragmented distribution. It is well represented throughout the Mediterranean basin, with more than 70 known species and widespread in the Southern ground waters of France [56].

The species present in the Baget system was first described as M. rouchi (Coineau 1968), originally distributed in the subterranean waters of the Nive, Laran and Kakoueta rivers in the north of the Pays Basque, as well as in the subterranean waters of the Ariège river, its tributary the Hers and the Lachein. In 2013, the specimens of the Ariège, the Hers and the Lachein were shown to differ from the first description of M. rouchi and were assigned to a new species M. ariegensis (Coineau, Boutin & Artheau, 2013). In the Baget system, it was first collected at the Lachein hyporheic [57], and then found at Exsurgence de Las Hountas, Moulo de Jaur, Puits de la Hillère and Grotte de Sainte-Catherine [51].

Stenasellus virei Dollfus, 1897 is represented in the Baget system by two subspecies: S. virei hussoni Magniez, 1968 and S. virei boui Magniez, 1968 [58]. The specimens of the two subspecies are elongated, about 6 to 10 mm long, pinkish in color. S.virei hussoni is found in Exsurgence de Las Hountas, Moulo de Jaur, Puits de la Hillère, Gouffre de la Peyrère and Grotte de Saint-Catherine. The subspecies is widespread. S. virei boui is an endemic subspecies known only from a few localities in Ariège. Slightly thinner and whiter than S. virei hussoni, it is typical of interstitial environments. In the Baget system, it is found in the hyporheic of Lachein [59].

4.2. Terrestrial Fauna

Except for the Coleoptera, which have undergone more intense sampling (Table 5), all the specimens are cited from Grotte de Sainte-Catherine.

Table 5.

Coleoptera of the Baget system, with their location and bibliographical references.

4.2.1. Palpigradi

All the palpigrades live either in the soil or in caves and are both anophtalmous and apigmented. Unlike tropical areas where endogenous species prevail, most of the European species live in caves. The very rare Eukoenenia pyrenaella Condé, 1990 has only been collected once and by a single specimen from the Sainte-Catherine cave [60].

4.2.2. Araneae

Among the many spiders found in the caves of the Baget system—seven common troglophilous species from the Sainte-Catherine cave (Déjean—com. pers.)—only one species, Leptoneta convexa Simon, 1873, can be considered troglobiotic [61]. Collected by Coiffait in 1950 in the Aven de Sainte-Catherine, it has never been recorded since [62].

4.2.3. Chilopoda

The only troglobiont known from the system, Lithobius cavernicola Fanzago, 1877 is endemic to the eastern Pyrenees [63].

4.2.4. Diplopoda

Blaniulus lorifer consoranensis (Brölemann, 1921) is a troglobitic species very common in the caves of Couserans (Ariège) and Comminges (Haute-Garonne).

4.2.5. Isopoda

Only one troglobitic Oniscoidae, Scotoniscus macromelos macromelos Racovitza, 1908 is known from the Baget karstic system. Scotoniscus macromelos is endemic of central Pyrenees.

4.2.6. Collembola

So far, four troglobiotic and three troglophilic species have been collected in the caves of the Baget system, mainly in Grotte de Sainte-Catherine. Among the troglobiotic species, a new species not yet described belongs to the genus Micronychiurus. Its troglobiotic status requires confirmation. The genus Micronychiurus is widespread along the Pyrenean range and highly diversified in caves and deep soils. Another new species belongs to Oncopodura of the crassicornis group and seems to be close to O. pelissiei from the karst of Quercy (North of Toulouse) [64]. Pseudosinella theodoridesi Gisin & Gama, 1969 and Tomocerus problematicus Cassagnau, 1964 are two endemic species, frequent in a few caves of the Couserans (western Ariège) and Comminges (Haute-Garonne) regions, where they often co-occur. Despite their status as strict troglobionts, they have retained reduced pigmentation and eyes.

4.2.7. Coleoptera (Table 5)

Only a few caves of the system were sampled for beetles, but the number of species is high: six species of the genus Aphaenops, genus endemic and emblematic of the Pyrenees, and one species of Leiodidae Leptodirini, Speonomus infernus infernus Coiffait, 1959, a species widespread in Ariège and Haute-Garonne.

The species composition is largely overlapping that of the Coume Ouarnède system, 5 of the 6 species beeing co-shared by the two systems. Only the species A. sinester Coiffait, 1959 is lacking from the Coume Ouarnède system.

Carabidae

Aphaenops (Hydraphaenops) cerberus bruneti is a species widespread and common in the caves of the area (Figure 6). The population of the Baget system is not genetically distinct from the specimens from the rest of the massif of Lestelas-Balaguères and Arbas massifs [68].

Figure 6.

Aphaenops (Hydraphaenops) cerberus bruneti from Grotte de l’Espugue. (Lestelas-Balaguères massif). Photo S. Huang.

- Aphaenops (Hydraphaenops) sinester

This enigmatic species, described from the Aven de Sainte-Catherine, known by very few specimens from this cave and the nearby Grotte de Liqué, is morphologically very close to Aphaenops pluto (Dieck, 1869), a species common on the other side of the Lez valley (Sourroque massif). Aphaenops sinester was described as a subspecies of A. pluto (Coiffait, 1959), but recently regarded as a distinct species [87]. More material would be required to confirm its validity.

Aphaenops (Hydraphaenops) tiresias tiresias and A. bucephalus, both uncommon, are nevertheless known from several caves of the Lestelas-Balaguères and Arbas massifs (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Aphaenops (Hydraphaenops) tiresias feeding on a Diptera (Limoniidae). Grotte du Goueil-di-Her, Coume Ouarnède system. Photo A. Faille.

Surprisingly, none of those two species were found in Grotte de Sainte-Catherine. They are until today only known from Gouffre de la Peyrère. This disparity between Gouffre de la Peyrère and Grotte de Sainte-Catherine, although very close, roughly matches that observed for aquatic fauna, and raises questions about potential barriers to dispersion or ecological heterogeneity within the Baget system.

Aphaenops (Argonotrechus) orpheus ssp. consorranus is rather an endogean subspecies, not rare in caves or under stones in forest on the Lestelas-Balaguères and Arbas massifs. Being often mentioned as a troglobitic species (e.g., [81]), we listed it here as such.

Leiodidae

The only species of cave Leiodidae, Speonomus (Machaeroscelis) infernus, is common and occurs in several caves of Ariège and Haute-Garonne (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Speonomus (Machaeroscelis) infernus from Grotte de l’Espugue, Lestelas-Balaguères massif. Photo C. Vanderbergh.

Representatives of the endogean genus Bathysciola are also present, with many narrow endemics (e.g., B. arcuatipes Jeannel, 1924, B. lapidicola Saulcy, 1872, B. liqueana Fresneda, Bourdeau & Faille, 2010) in the area [88]. Their presence in the studied area remains to be confirmed.

4.2.8. Laboulbeniales

Laboulbeniales are highly specialized parasitic fungi that are found exclusively on insects, arachnids and myriapods. The genus Rhachomyces parasitizes many species of different subgenera of Aphaenops. Among the five species paraziting Aphaenops, Rhachomyces aphaenopsis Thaxter, 1905 is the most common [75]. It has been found in Aven de Ste Catherine, on A. cerberus bruneti [65,75,89], on A. sinester [75] and on A. ehlersi [65,75]. In the Gouffre de la Peyrère, it was recorded on A. bucephalus [75]. Even if not specifically reported for the area, all the Trechini species (A. bucephalus, A. cerberus, A. ehlersi, A. orpheus, A. sinester, A. tiresias) present in the Baget system are known to host the species.

5. Discussion

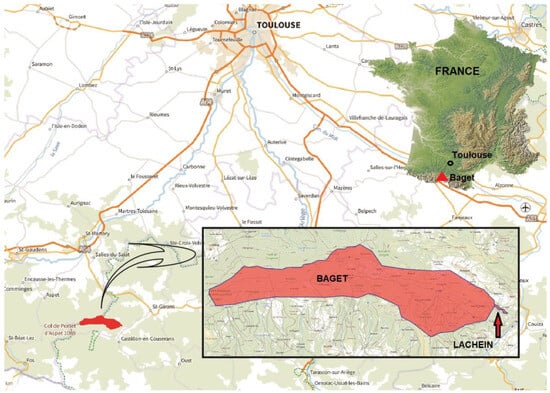

In view of the taxa listed above, the Baget system deserves to be qualified as a hotspot for underground biodiversity. With 40 stygobiotic and 17 troglobiotic species, it is even to date the richest in the Pyrenees, ahead of Coume Ouarnède (21 stygobiotic and 17 troglobitic species) [2]. In addition to the number of species, its richness is also measured by the large number of higher-rank taxa and the presence of narrow endemic species (Cookidrilus ruffoi Giani, Martinez-Ansemil & Sambugar, 2004 for the hyporheic environment, Antrocamptus catherinae Chappuis & Rouch, 1960 for the karst groundwater, and Eukoenenia pyrenaella Condé, 1990 for the terrestrial environment).

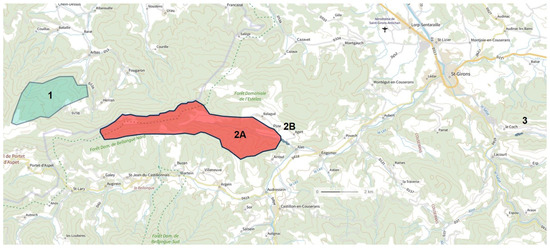

Although the size of the catchment is relatively small (13.5 km2), the system offers a large number of subterranean habitats, which can partly explain this richness. Above all, this strong biodiversity can be linked to its presence in a particularly rich sector, the Central Pyrenees. It may be interesting to compare the Baget biocenoses of the two neighboring Pyrenean hotspots: the Nert for the hyporheic fauna and the Coume Ouarnède system [2,90,91] (Figure 9 and Table 6).

Figure 9.

Location of the 3 Pyrenean subterranean hotspots. 1: Coume Ouarnède System; 2A: Baget System; 2B: Hyporheic of Lachein stream; 3: Hyporheic of Nert stream.

Table 6.

Comparative biocenosis of Baget system, Coume Ouarnède system and the hyporheic of Nert stream. CO = Coume Ouarnède.

For the terrestrial fauna, the Baget and the Coume Ouarnède are two contiguous systems, but with a faunistic assemblage very distinct from each other. Of 26 species present in total, only 8 are present on both sites. Richness is similar on both systems, with 17 troglobionts. In Coume Ouarnède system, it includes two remarkable relict species, the opilion Arbasus caecus (Simon, 1911) [92] and the springtail Tritomurus falcifer Cassagnau, 1958, which are absent in the Baget system. On the other hand, we find in Baget a strictly endemic species, Eukoenenia pyrenaella Condé, 1990.

For aquatic fauna, Coume Ouarnède system hosts fewer troglobionts (22) than Baget system (40). Two hypotheses may explain this. First, a less extended hyporheic habitat in Coume Ouarnède and second, a much more in-depth study of the aquatic fauna of the Baget catchment (Table 7). Rouch’s work, conducted over a period of more than 30 years, and concerning both karst and hyporheic habitats, provides us with a detailed and complete knowledge of the stygofauna, probably unmatched at the European scale. Of a total of 49 to 50 species (uncertainty due to the unidentified Salentinella sp. in Coume Ouarnède), only 10 to 12 are present on both sites. If we compare the data of Baget with those of Nert [91], the number of species is again greater in Baget. Nevertheless, we obtain similar results if we consider the hyporheic environment only with 29 species in Nert and 31 in Baget. It can be noted that although the surface studied in the hyporheic of Nert is larger, the sampling was less intense. Of a total of 49 species on these two sites, 18 are present in both. Baget, Nert and Coume Ouarnède altogether host 56 stygobionts, among which only 10 are common to the three sites.

Table 7.

Distribution of stygobionts between hyporheic and karstic habitats for the Baget system, the Coume Ouarnède system, and the hyporheic of the Nert.

All these results lead us to believe that regarding aquatic fauna, the data collected in the Baget catchment reflect the reality of the population. No region of the Pyrenees has been the site of such an intense collection effort, and, given the fragmentary data available [20], it is very likely that more in-depth studies on other aquatic habitats, including Nert and Coume Ouarnède, would lead to a significant increase in the underground biodiversity of the central Pyrenees.

Concerning the troglofauna of the system, the data come only from a few caves, mostly Grotte de Sainte-Catherine. Furthermore, many taxonomic groups such as Acari, Pseudoscorpiones, Oniscida, Diplura are poorly or not represented, probably due to insufficient sampling. The significant speleological developments of the last 15 years have opened up a vast field of study, which could lead, if biospeleologists get down to it, to new discoveries.

Author Contributions

All the authors participated in all phases of the realization and writing of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Louis Deharveng for his support all along the realization of the paper and providing access to his database. We thank Vincent Prié for his help on Gastropoda, Christian Vanderbergh and Sunbin Huang for providing pictures of Coleoptera. We are grateful to Daniel Quettier (Société Méridionale de Spéléologie et de Préhistoire) for his important inventory work of the Pyrenean caves and for giving us access to all his data. In general, we thank all the cavers (among them, Groupe Spéléologique du Couserans, Spéléo Club de l’Epia) with whom we continue to explore and study the caves of the Estelas-Balaguères massif.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Culver, D.C.; Deharveng, L.; Pipan, T.; Bedos, A. An overview of subterranean biodiversity hotspots. Diversity 2021, 13, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faille, A.; Deharveng, L. The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France). Diversity 2021, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Société Méridionale de Spéléologie et de Préhistoire. Bulletins de la Section Spéléologie. Available online: http://smsp-speleo.blogspot.com/p/bibliotheque-pdf.html (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Mangin, A. Le système karstique du Baget (Ariège) (note préliminaire). Ann. Spéléo. 1970, 25, 561–580. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, B.; Malard, A. Système souterrain de l’Hider. Spéléo Mag. 2019, 108, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bréhier, F.; Tixier, G. Reprise des explorations sur le réseau du Pas du Loup—Francazal (Haute-Garonne). Le Fil 2013, 25, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Spéléo-Club EPIA. Le spéléo-club EPIA: Un club de la balle atomique! Spelunca 2014, 133, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanel, P. Aliou 2019. Le Fil 2020, 30, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo, S.; Marguet, T.; Burle, C.; Gould, V. Le gouffre de la Lune—Haute-Garonne: Récit d’une exploration estélassienne. Spéléo Mag. 2022, 118, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mangin, A. Contribution à l’étude hydrodynamique des aquifères karstiques: Première partie Généralités sur le karst et les lois d’écoulement utilisées. Ann. Spéléo. 1974, 29, 283–332. [Google Scholar]

- Mangin, A. Contribution à l’étude hydrodynamique des aquifères karstiques: Deuxième partie Concepts méthodologiques adoptés. Systèmes karstiques étudiés. Ann. Spéléo. 1974, 29, 495–601. [Google Scholar]

- Mangin, A. Contribution à l’étude hydrodynamique des aquifères karstiques: Troisième partie Constitution et fonctionnement des aquifères karstiques. Ann. Spéléo. 1975, 30, 21–124. [Google Scholar]

- Debroas, E.J. Géologie du bassin versant du Baget (zone nord-pyrénéenne, Ariège, France): Nouvelles observations et conséquences. Strata 2009, 46, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Marsaud, B. Structure et Fonctionnement de la Zone Noyée des Karst à Partir des Résultats Expérimentaux; Editions BRGM: Orléans, France, 1997; 306p. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Recherches sur les eaux souterraines. 17. Le système karstique du Baget. II. Etude des Harpacticides rejetés au niveau de Las Hountas au cours de plusieurs crues du cycle hydrologique 1970–1971. Ann. Spéléo. 1972, 27, 139–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Recherches sur les eaux souterraines. 24. Le système karstique du Baget. III. Etude des sorties d’Harpacticides au niveau de Las Hountas lors de plusieurs crues des cycles hydrologiques 1971–1972 et 1972–1973. Ann. Spéléo. 1974, 29, 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R.; Pitzalis, A.; Descouens, A. Effets de pompage à gros débit sur le peuplement des Crustacés d’un aquifère karstique. Ann. Limn. 1993, 29, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R. Sur la répartition spatiale des Crustacés dans le sous-écoulement d’un ruisseau des Pyrénées. Ann. Limn. 1988, 24, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannel, R. Quarante années d’explorations souterraines. Notes Biospéologiques 1950, 6, 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- Juberthie, C.; Ginet, R. France. In Encyclopaedia Biospeologica; Tome 1; Juberthie, C., Decu, V., Eds.; Société de Biospéologie: Moulis, France, 1994; pp. 665–692. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, R. Faune Cavernicole de la France; Lechevalier: Paris, France, 1926; 334p. [Google Scholar]

- Renauld, P. Etude géomorphologique des grottes de Sainte-Catherine (Ariège). Ann. Spéléo. 1969, 24, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Juberthie, C. Etude écologique des larves de Speonomus infernus dans la grotte de Sainte-Catherine. Ann. Spéléo. 1969, 24, 563–577. [Google Scholar]

- Juberthie, C. Relation entre le climat, le microclimat et les Aphaenops cerberus de la grotte de Sainte-Catherine (Ariège). Ann. Spéléo. 1969, 24, 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Andrieux, C. Etude du climat de la grotte de Sainte-Catherine en Ariège selon le cycle de 1967. Ann. Spéléo. 1969, 24, 19–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa-Cedamanos, F.; Probst, J.L.; Binet, S.; Camboulive, T.; Payre-Suc, V.; Pautot, C.; Bakalowicz, M.; Beranger, S.; Probst, A. A forty-year karstic critical zone survey (Baget Catchment, Pyrenees-France): Lithologic and hydroclimatic controls on seasonal and inter-annual variations of stream water chemical composition, pCO2, and carbonate equilibrium. Water 2020, 12, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, C.; Rouch, R. Un nouveau champ de recherches sur la faune aquatique souterraine. Compte Rendu L’académie Sci. Paris 1967, 265, 369–370. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Contribution à la connaissance des Harpacticides hypogés (Crustacés Copépodes). Ann. Spéléo. 1968, 23, 5–167. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R.; Bonnet, L. Le système karstique du Baget. IV. Premières données sur la structure et l’organisation de la communauté des Harpacticides. Ann. Spéléo. 1976, 31, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R.; Bonnet, L. Le système karstique du Baget. V. La communauté des Harpacticides. Sur la constance du peuplement. Ann. Spéléo. 1976, 31, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Le système karstique du Baget. XII. La communauté des Harpacticides. Sur l’interdépendance des nomocénoses épigée et hypogée. Ann. Spéléo. 1982, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R. Le système karstique du Baget. XIII. Comparaison de la dérive des Harpacticides à l’entrée et à la sortie de l’aquifère. Ann. Limn. 1982, 18, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R.; Carlier, A. Le système karstique du Baget. XIV. La communauté des Harpacticides épigés. Evolution et comparaison des structures du peuplement épigé à l’entrée et à la sortie de l’aquifère. Stygologia 1985, 1, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R.; Carlier, A. Le système karstique du Baget. XV. Le peuplement des Harpacticides épigés. Analyse des prélèvements synchrones à l’entrée et à la sortie de l’aquifère. Stygologia 1985, 1, 224–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R.; Bakalowicz, M.; Mangin, A.; D’hulst, D. Sur les caractéristiques chimiques du sous-écoulement d’un ruisseau des Pyrénées. Ann. Limn. 1989, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R.; Lescher-Moutoué, F. Structure du peuplement des Cyclopides (Cructacea: Copepoda) dans le milieu hyporhéique d’un ruisseau des Pyrénées. Stygologia 1992, 7, 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Route, N.; Martinez-Ansenil, E.; Sambugar, B.; Giani, N. On some interesting freshwater Annelida, mainly Oligochaeta, of the underground waters of southwestern France with the description of a new species. Subteranea Biol. 2004, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- MNHN & OFB (Ed.). Inventaire National du Patrimoine Naturel (INPN). 2003–2023. Available online: https://inpn.mnhn.fr (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Bertrand, A.; Bréhier, F.; Dumas, P.; Juberthie, C.; Mangin, A.; Cabrol, P.; Grassaud, M. Projet de Réserve Naturelle Souterraine de l’Ariège. Sites, Paysages, Nature; Préfecture de l’Ariège & DREAL Midi-Pyrénées: Toulouse, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zagmajster, M.; Malard, F.; Eme, D.; Culver, D.C. Subterranean Biodiversity Patterns from Global to Regional Scales. In Cave Ecology; Ecological Studies (Analysis and Synthesis); Moldovan, O., Kováč, Ľ., Halse, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 235, pp. 195–227. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Structure du peuplement des Harpacticides dans le milieu hyporhéique d’un ruisseau des Pyrénées. Ann. Limn. 1991, 27, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R. Caractéristiques et conditions hydrodynamiques des écoulements dans les sédiments d’un ruisseau des Pyrénées. Implications écologiques. Stygologia 1992, 7, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R.; Bonnet, L. Le système karstique du Baget. VI. La communauté des Harpacticides. Signification des échantillons récoltés lors des crues au niveau de deux exutoires du système. Ann. Limn. 1977, 13, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R.; Bonnet, L. Le système karstique du Baget. VII. La communauté des Harpacticides. Structure du peuplement hypogée pendant les crues. Ann. Limn. 1977, 13, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R. Le systèmes karstique du Baget. VIII. La communauté des Harpacticides. Les apports au sein du système par dérive catastrophique. Ann. Limn. 1977, 15, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rouch, R. Le systèmes karstique du Baget. X. La communauté des Harpacticides. Richesse spécifique, diversité et structures d’abondances de la nomocénose hypogée. Ann. Limn. 1980, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouch, R. Le système karstique du Baget. XI. La communauté des Harpacticides. Sur l’évolution de la nomocénose épigée au sein de l’aquifère. Ann. Limn. 1980, 16, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rouch, R. Le systèmes karstique du Baget. IX. La communauté des Harpacticides. Richesse spécifique, diversité et structure d’abondances des échantillons de dérive au niveau du ruissellement de surface. Vie Milieu 1980, 30, 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Meisch, C.; Smith, R.J.; Martens, K. A subjective global checklist of the extant non-marine Ostracoda (Crustacea). Eur. J. Taxon. 2019, 492, 1–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamare Deboutteville, C.; Chappuis, P.A. Les Bathynelles de France et d’Espagne avec diagnoses d’espèces et de formes nouvelles. Vie Milieu 1954, 4, 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Recherches sur les eaux souterraines. 12. Le système karstique du Baget. I. Le phénomène d’hémorragie au niveau de l’exutoire principal. Ann. Spéléo. 1970, 25, 667–709. [Google Scholar]

- Serban, E.; Coineau, N.; Delamarre-Deboutteville, C. Recherches sur les Crustacés souterrains et mésopsamiques. I—Les Bathynellacés Malacostraca des régions méridionales de l’Europe occidentale. La sous-famille des Gallobathynellinae. Mémoires Du Muséum Natl. D’histoire Nat. Série A Zool. 1972, 75, 7–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rouch, R. Peuplement des Crustacés dans la zone hyporhéique d’un ruisseau des Pyrénées. Ann. Limn. 1995, 31, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginet, R. Bilan systématique du genre Niphargus en France. Soc. Linn. Lyon 1996, 1–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bou, C. Recherches sur les eaux souterraines XVI. Parasalentinella rouchi n.gen.,n.sp. des eaux souterraines des Pyrénées francaises (Amphipoda, Gammaridea). Ann. Spéléo. 1971, 26, 481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Coineau, N.; Boutin, C.; Artheau, M. Origin of the interstitial isopod Microcharon (Crustacea, Microparasellidae) from the western Languedoc and the northern Pyrenees (France) with the description of two new species. Subterr. Biol. 2013, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coineau, N. Contribution à l’étude de la faune interstitielle. Isopodes et Amphipodes. Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle Paris, N.S. Ann. Zool. 1968, 55, 147–216. [Google Scholar]

- Magniez, G. L’espèce polytypique Stenasellus virei Dollfus, 1897 (Crustacé Isopode Hypogé). Ann. Spéléo 1968, 23, 363–407. [Google Scholar]

- Magniez, G. Observations sur Stenasellus virei (Crustacea, Isopoda, Asellota) dans ses biotopes naturels des eaux souterraines. Int. J. Speleol. 1974, 6, 115–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condé, B. Palpigrades (Arachnida) de grottes d’Europe. Rev. Suisse Zool. 1989, 96, 823–840. [Google Scholar]

- Le Peru, B. The spiders of Europe, a synthesis of data: Volume 1. Atypidae to Theridiidae. Mém. Soc. Linn. Lyon 2011, 2, 1–522. [Google Scholar]

- Dresco, E. Etude des Leptoneta. Leptoneta convexa Sim. et microphtalma Sim. (Aranaeae Leptonetidae). Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Toulouse 1980, 116, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Iorio, E. Catalogue biogéographique et taxonomique des Chilopodes (Chilopoda) de France métropolitaine. Mém. Soc. Linn. Bordeaux 2014, 15, 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- Deharveng, L. Collemboles cavernicoles VIII. Contribution à l’étude des Oncopoduridae. Bull. Soc. Ent. Fr. 1988, 92, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer-Lefèvre, N.H. Recherches sur les Laboulbéniales des Trechinae cavernicoles pyrénéens. Ann. Spéléo. 1965, 20, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Coiffait, H. Biospeologica LXXVII. Enumération des grottes visitées (Neuvième série). Arch. Zool. Exp. Gén. 1959, 97, 209–465. [Google Scholar]

- Faille, A. Endémisme et Adaptation à la Vie Cavernicole Chez les Trechinae Pyrénéens (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Approches Moléculaire et Morphométrique. Ph.D. Dissertation, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Faille, A.; Tänzler, R.; Toussaint, E.F.A. On the way to speciation: Shedding light on the karstic phylogeography of the micro-endemic cave beetle Aphaenops cerberus in the Pyrenees. J. Hered. 2015, 106, 692–699. [Google Scholar]

- Jauzion, G. Activités de la section spéléologie—1990–1991. Bull. Soc. Mérid. Spéléo. Préhist. 1991, 31, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, R. Les Trechinae de France (Deuxième Partie). Ann. Soc. Entom. France 1921, 90, 295–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannel, R. Monographie des Trechinae (Troisième livraison). Les Trechini cavernicoles. L’Abeille 1928, 35, 1–808. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, R. Faune de France. Coléoptères Carabiques I, Vol. 39; P. Lechevalier: Paris, France, 1941; 571p. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, R. Faune de France. Vol. 51: Coléoptères Carabiques (Supplément); P. Lechevalier: Paris, France, 1949; 51p. [Google Scholar]

- Juberthie, C.; Massoud, Z.; Piquemal, F. L’équipement sensoriel des Trechinae souterrains. I.—Les organes sensoriels de l’élytre. Ann. Spéléo. 1975, 30, 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, S.; Faille, A. Rhachomyces (Ascomycota, Laboulbeniales) parasites on cave-inhabiting Carabidae beetles from Pyrenees. Nova Hedwig. 2007, 85, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffait, H. Note sur les Trechidae cavernicoles et endogés de la région Pyrénéenne. Notes Biospéologiques 1958, XIII, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Coiffait, H. Localités nouvelles ou peu connues de Coléoptères cavernicoles (Pyrénées centrales). Bull. Soc. Mérid. Spéléo. Préhist. 1962, 9, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Coiffait, H. Monographie des Trechinae cavernicoles des Pyrénées. Ann. Spéléo. 1962, 17, 119–170. [Google Scholar]

- Coiffait, H. Nouveaux Trechini cavernicoles des Pyrénées françaises. Ann. Spéléo. 1959, XIV, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Déliot, P. Coléoptères Trechinae et Bathysciinae peuplant le domaine souterrain du département de l’Ariège. Liste des espèces, localisations et observations. Ariège Nat. 1995, 5, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Faille, A.; Ribera, I.; Deharveng, L.; Bourdeau, C.; Garnery, L.; Queinnéc, E.; Deuve, T. A molecular phylogeny shows the single origin of the Pyrenean subterranean Trechini ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2010, 54, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffait, H. Note sur les premiers états de Geotrechus orpheus ssp. consorranus et sur la biologie larvaire de ce coléoptère. Vie Milieu 1951, II, 461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Fourès, H. Localités nouvelles ou peu connues de coléoptères cavernicoles des Pyrénées françaises. Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Toulouse 1947, 82, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mouriès, M. Fiche cavité. In Fichier Spéléologique Du Comité Spéléologique Régional de Midi-Pyrénées; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, R. Révision des Bathysciinae (Coléoptères, Silphides). Morphologie, distribution géographique, Systématique. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gén. 1911, 47, 1–641. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, R.; Racovitza, E. Enumération des grottes visitées, 1908–1909 (Troisième série). Biospeologica XVI. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gén. 1910, 5, 67–185. [Google Scholar]

- Quéinnec, E.; Ollivier, E. Tribu Trechini. In Faune de France 94. Coléoptères Carabiques, Compléments et Mise à Jour; Coulon, J., Pupier, R., Quéinnec, E., Ollivier, E., Richoux, P., Eds.; Fédération Française des Sociétés de Sciences Naturelles: Paris, France, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 19–254. [Google Scholar]

- Tronquet, M. (Ed). Catalogue des Coléoptères de France; Association Roussillonnaise d’Entomologie: Perpignan, France, 2014; 1052p. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, S. Els Rhachomyces (Laboulbeniales, Ascomycotina) paràsits dels caràbids troglobionts als Pirineus. Orsis 1989, 4, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Danielopol, D.L.; Rouch, R.; Bou, C. High Amphipoda Species Richness in the Nert Groundwater System (Southern France). Crustaceana 1999, 72, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielopol, D.L.; Rouch, R.; Baltanas, A. Taxonomic diversity of groundwater Harpacticoida (Copepoda, Crustacea) in Southern France. A contribution to characterise hot-spot diversity sites. Vie Milieu 2002, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, I. Arbasus caecus (Simon, 1911): A new member of the ancient family Buemarinoidae (Opiliones, Laniatores) and its relation to the known species. Biol. Serbica 2023, 45. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).