Abstract

Several factors contributed, over time, to the Mediterranean monk seal’s sharp population decline. Despite the relative disappearance of documented breeding sub-populations, sightings have been collected, in recent decades, from most of the species’ former habitat. The conservation of this endangered marine mammal should also encompass those areas. We conducted our research along the coast of Salento (South Apulia, Italy) as a case study. To collect data on monk seal presence in the area, expected to be characterized by low numbers, we combined three different methodologies: a questionnaire to fishermen, interviews with witnesses of sightings, and a historical review of the species’ presence. The different methodologies allowed us to collect 11 records of recent sightings (after 2000) and 30 records of historical encounters (before 2000), highlighting that the species was already rare in Salento over the last century. Most of the historical information was concentrated between 1956 and 1988 (28 records), suggesting discontinuous occurrence in the area, possibly depending on the lack of monitoring efforts. Furthermore, a broad regional approach should be considered as a more effective path to aid the monk seal recovery, better comprehend the species’ abundance and movements, and eventually contribute to the overall health of ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus, Hermann 1779)—hereafter MMS—populations were once distributed along the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and the coasts of the eastern Atlantic, from Spain to the Gambia, including Macaronesia (from the Azores to Cape Verde) [1,2]. Over the centuries, the species has experienced a sharp reduction in population abundance and distribution [3,4]. Direct killing, accidental capture/killing, disturbance, habitat loss, pollution, overfishing, diseases, and low genetic variability are among the factors that might have contributed to the species’ decline over the last century [5]. Some of these stressors act directly on the survival of the species (e.g., death of animals), while others do so indirectly (e.g., reducing the chance of reproduction). Nowadays, the main threats to the survival of the species are represented by the interaction with fisheries (direct impact) along with the reduction of available habitat (indirect impact) [2,6,7,8]; artisanal fisheries with static nets represent the highest direct impact on the species [9,10].

1.1. Fishermen’s Knowledge

Coastal fishermen and seals compete for the same resources, fishermen may kill animals that damage their catch and nets, or seals can become entangled in the nets and drown [11]. Fishermen represent the stakeholders most likely to encounter a seal since they spend most of their time in waters close to the coast. Fishermen’s knowledge and their involvement in scientific surveys have been increasingly used in research studies to assess commercial and non-commercial marine species, as well as current and historical population abundances and trends, otherwise unrecorded [9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Artisanal fishermen have been shown to be an important category of stakeholders in the cooperation for the conservation of coastal marine ecosystems and management of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) [23,24,25]. Small-scale fishing is an integral part of the cultural, social, and economic heritage of Mediterranean countries [26,27]. Furthermore, fishermen face a number of issues, including over-exploitation of fishery resources and competition with other fishing systems (including illegal fishing) and are the main stakeholder subjected to restrictions as a result of environmental protection (e.g., no-fishing zone, no-fishing season).

1.2. Monk Seal Sightings

The MMS, classified as Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [28], is internationally protected by environmental agreements and legal frameworks, deserving full protection of every single individual as well as their habitat. Furthermore, in recent years, the importance of extending the protection of the species and its habitat to wider regions has been widely recognized, considering the possible re-colonization or movement of animals [29,30,31,32]. This is important, particularly in areas defined as “Low-Density Areas” where sightings have been recorded, despite their disappearance and relative distance to known reproductive populations [30]. The current known MMS population in the Mediterranean consists of approximately 350–450 individuals, predominantly confined along the coasts of Greece and Turkey [2,8]. This estimate does not consider the sightings of monk seal individuals that have been reported elsewhere in its ancient distribution, although it is unclear whether those occurrences represent vagrants, animals coming from the remnant breeding sub-populations, or residuals of larger ancient populations [2,29]. The presence of MMS in areas where the species is not regularly encountered, or the information about it is scarce or completely lacking, might result in undetected occurrences [29,33].

Involving the public in scientific surveys (citizen science) to collect sightings data can be useful in improving the assessment of marine mammals’ presence/abundance [34,35,36,37,38]. In addition, a sightings network should represent an easy and rapid process to communicate information, allowing direct contact with the occasional witness of an encounter and increasing data logging. It is essential that the validation process of the information collected through the network follows accurate scientific protocols [15,18,29,39,40].

The MMS was known to frequent the Italian coasts; however, stable reproductive populations have disappeared since the 1980s [41,42]. Nevertheless, several seal sightings have been reported from the key areas of the species’ former known habitat, up to and including the present [29,42,43]. As a result, its conservation status in Italy has been updated to “Data Deficient” [44,45].

1.3. MMS Historical Presence

The retrieval and analysis of historical data on a species in a given area can provide crucial information for understanding its occurrence, abundance, and useful knowledge for managing its conservation and eventually aiding its recovery. The relative scarcity of records cannot be interpreted simply as the absence of a species; it could depend on the low number of individuals to be detected, on the skill and experience of a researcher, or on the lack of long-term monitoring surveys over time [21,46,47,48]. False absence, “a non-detection that is treated mistakenly and with certainty as a true absence” [49] (p. 625), needs to be considered when approaching historical data. Historical data might be difficult to access; moreover, data derived from different sources (i.e., museum achieves, grey literature) might prove difficult to compare with that recorded through scientific surveys with standardized methodologies. Analysing historical data requires a careful reanalysis effort, which also involves removing data with extreme uncertainty of location and date [21,49].

The present research was carried out along the coast of Salento (South Apulia, Italy) as a “Low-Density Area” (LDA) case study. Evidence of monk seal occurrences on the coast of Salento date back to ancient times, with a relatively low abundance reported already over the last four centuries [50,51,52,53,54]. However, specific studies on the historical trend of population abundance or dedicated monitoring surveys have not been systematically conducted in the area, with the exception of a few opportunistic reviews on sightings during the 1980s–1990s.

The aim of the present study is to provide an evaluation of the past and present status of the MMS and to propose an improvement of conservation measures for the species. To investigate this species, regarded as elusive, we combined three different methodologies: (i) a questionnaire to coastal fishermen (methodology A); (ii) interviews with witnesses of MMS sightings recorded throughout a network of information and validated using a specific protocol (methodology B); and (iii) compilation of historical data on MMS presence (methodology C).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

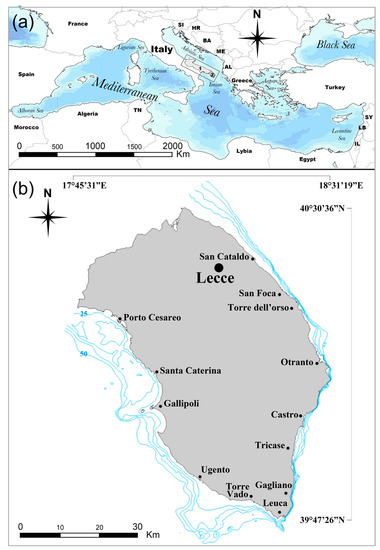

Situated in the southwestern part of the Adriatic Sea, the Salento peninsula is the southern tip of the Apulian region (Italy), located ~75 km from Albania as well as from the Northern Ionian Islands (Greece). The Salento coastline, corresponding with the province of Lecce, extends for ~250 km, from the north of San Cataldo to the east, to the north of Porto Cesareo to the west (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Area. In (a), the geographical contextualization of the study area is within the Mediterranean Sea. The Apulian region (1) and the Salento peninsula (2) are inside the rectangle. In (b), the map of Salento, with the main locations in the area.

Two hundred seventy-one fishing vessels operating in the area with coastal static fishing nets (trammel, gill nets, and bottom longlines) were registered in 2013 at the local port authorities (European Community Fishing Fleet Register online database, http://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/fleet/index.cfm, accessed on 10 September 2013). The main fishing districts and ports along the coast of Salento (from east to west) were represented by San Cataldo, San Foca, Otranto, Castro, Tricase, Leuca, Torre Vado, Ugento, Gallipoli, and Porto Cesareo.

The survey to investigate monk seal presence and sightings in the study area was carried out between January 2013 and August 2015, using three research methodologies, in details described in the following paragraphs.

2.2. Fishermen’s Interviews

A questionnaire was specifically designed to interview fishermen (research methodology A). The questionnaire was elaborated in an implicit mode in order to encourage answers on the MMS, to avoid recording misleading or deceptive answers, and to avoid providing the interviewee with advance notice of the investigation subject. We followed the example of Boyd and Stanfield [55] used for the Caribbean monk seal (Neomonachus tropicalis Gray, 1950), which was also applied by Mo et al. [56,57,58,59] and Hamza et al. [60] for the MMS. To elaborate the questionnaire and formulate the questions, previous studies based on questionnaires on fishing activities [19,61,62,63,64] and on the socio-economic impact of environmental conservation measures on fishery [65,66,67,68] were considered. We designed a semi-structured interview questionnaire with a combination of open- and close-ended questions to record the perceptions of the fishermen regarding specific issues (i.e., MMS presence, fishery-related problems, and conservation practices). The questionnaire consists of 30 questions organised in 5 themes (see Supplementary Material File S1 for the complete questionnaire):

- (1)

- Personal information on the fishermen and employment details on the fishing activity (i.e., age, years of fishing activities, family, boat dimension, crew, fishing cooperative, and other activities);

- (2)

- Information about the fishing activity (i.e., period, area, species, gears);

- (3)

- Information on nets and catch damage and their compensation (i.e., characteristics of net damage, frequency of occurrence, catch loss, causes, methods to avoid damages, compensative formulas);

- (4)

- Information on the presence of protected species: dolphins, monk seals, and marine turtles (i.e., periods, frequencies, interactions, and areas of the encounters);

- (5)

- Information regarding the overall state of local fish stocks and the protection of the environment (exploitation, protection, fishermen’s involvement in the decision process, and the trade-off between use and conservation).

The questionnaire was proposed to thirty-nine fishermen operating within the area with static nets, with fishermen’s vessels having been registered in 2013 at the local port authority from the main ports of Salento, representing about 15% of the total fishermen (see Supplementary Material File S2 for the distribution of the fishing vessels according to the fishing districts and ports in Salento). The fishermen (one member per boat, preferably the owner) were interviewed individually by the same person in order to reduce the discrepancy in collecting the data and to avoid doubts during data analysis. The frequency of the answers was expressed in integer numbers rather than percentages to avoid the false impression of a large number of subjects greater than the real ones.

2.3. Interviews with Witnesses of MMS Sightings

In order to collect data on monk seal sightings from the local communities and tourist sector, a network of information was set up in collaboration with the University of Salento, the Marine Protected Area Porto Cesareo, the Parco Naturale Regionale Costa Otranto- Santa Maria di Leuca e Bosco di Tricase, and the “Corpo Forestale, Presidio San Cataldo (Lecce)”.

Whenever the information about an MMS sighting was received, including previous-in-time events, the witness was contacted directly by one of the authors (LB) and interviewed (research methodology B) using the protocol developed by the NGO “Archipelagos—environment and development” (Greece), improved with recent biological and ecological knowledge on the species [29,69].

The reliability of the data, in the absence of photographic documentation, was determined by the accuracy of the recorded information (date, time, and behaviour of the individual(s)). Some of the sightings, supported by a substantial number of witnesses and by the relatively close temporal range of reference, allowed a direct comparison and confirmation of the sighting. The sightings were not included when they had incomplete information and/or the description of the event presented inconsistency.

2.4. Compilation of Historical Presence

Historical research was conducted to compile old records about the occurrence of MMS in Salento (research methodology C). Historical occurrence data, as defined by Tingley and Beissinger [49], represent any set of records that provides evidence for the presence or absence of a species and can be derived from a variety of sources. Historical occurrence is distinct from long-term monitoring data (standardized and measured) and can contain anecdotal and general information. However, the data must contain at least sufficient information (i.e., explicit data on time and location) to be included in the research study. Information was collected from data reported in previous research studies and investigations on the issue, including Web of Science, ResearchGate and Google Scholar databases, and grey literature (e.g., “Catalogo delle Biblioteche di Ateneo” of the University of Salento). Osteological materials, stuffed specimens and photographic materials, and the testimony of MMS presence in Salento, preserved in public (museum) and private collections at local and national levels, were thoroughly investigated.

2.5. Combining the Methodologies

MMS sightings were classified as “historical” data if referring to sightings before the year 2000 and were classified as “recent” data if referring to sightings from the year 2000 onward.

The data collected throughout the three described methodologies were cross-referenced using the recent (resulting from methodologies A and B) and historical (resulting from methodologies A and C) classifications.

The entire dataset of sightings (historical and recent) was then combined and plotted. The information related to the MMS’s sightings was organized into Single Sighting Events (SSE = unit, regardless of the number of individuals sighted simultaneously) in order to make it comparable and to obtain a complete overview of the species along the coast of Salento.

3. Results

3.1. Fishermen’s Interviews

The questionnaire to fishermen (methodology A) was developed as a new tool to evaluate monk seal sightings in LDAs within the current research. Salento is the area chosen to test its effectiveness. The results of the interviews with fishermen using the questionnaire were organized into two main categories and presented in Table 1 (data on fishermen and fishing activity) and Table 2 (data on management and conservation of the environment). The majority of respondents (24/39) fell into the age class between 50–69 years, for a good portion (19/39) started fishing at a young age (<11 years). All of the interviewees belonged to a family of fishermen, most of them with relatives currently working in the field. The demographic data reflect a lack of recruitment of young people to the profession since all the relatives reported to work in the field were mostly included in the above-mentioned age class. About two-thirds of the interviewees completed secondary school (25/39) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data on Fishermen and Fishing Activities from the questionnaire to fishermen. Sorted by (1A) Demographic Characteristics of the Fishermen and (1B) Fishing Activity Characteristics and organized into categories, classes, and frequencies (F).

Table 2.

Data on Management and Conservation of the Environment from the questionnaire to fishermen. Sorted into (2A) Strategies to Minimize Net Damage, (2B) Protected Species Encounters, (2C) Fishing Resources, (2D) Environment Protection: Management, and (2E) Environment Protection: Trade-Off, and organized into categories, classes, and Frequencies (F).

The fishing vessels were typically <12 m long (33/39), operating with the support of other fishermen as crew (25/39). Most of the fishermen were registered in the main local fishery cooperatives. Fishery does represent the main activity, active year-round, mostly with mixed fishing instruments (35/39). Respondents generally reported fishing as their primary source of household income, and only four fishermen have a secondary job not related to fishing (Table 1). All the fishermen reported damage to nets and catches, and very few gave information about the damage and its cause. Only one fisherman reported that seals produce a central hole and two smaller side holes. On the other hand, damage related to wide lacerations from the bottom was ascribed to impact with the seabed in the presence of adverse weather conditions by all interviewees. Almost all fishermen (36) reported net damage due to dolphins. Twenty-five fishermen identified the compensatory formulas as the best solution to minimise damage, twenty-one of which preferred the supply of fishing tools rather than the monetary compensation (Table 2).

About half of the interviewees (15/39) were aware of the MMSs’ presence until the 1980s; however, in most cases, they provided only general information about the area and period that the animals were encountered. Only in three cases did we obtain specific information regarding a historical presence prior to 2000: in 1968 and 1973 near Ugento and in 1978 close to Leuca. Only three fishermen reported recent sightings (after 2000) of MMS: two animals north of Otranto in November 2013: one close to San Foca in July 2014, and another one in the area North of Castro in November 2014. Meanwhile, almost all confirmed the presence of marine turtles and dolphins in the past, as well as in the present time. Most of them outlined an increase in the presence of dolphins in recent times. All the fishermen believed that fish stocks were diminishing, identifying overfishing as the main reason (Table 2). The chosen option for the potential recovery of fish stocks was to ban the most invasive fishing methods (34/39), including net mesh size and recreational fishery. Other participants supported the establishment of Protected Areas (22/39) and fishing seasons (20/39). Almost all agreed on the involvement of the fishery stakeholders in the management and protection of the environment, with active participation in the processes (38/39) and the availability to collaborate with researchers (36/39). Fishermen responded positively, accepting limits to the fishing season (35/39), fishing methods (34/39), and fishing areas (30/39) in order to recover fish stock and protect the environment (Table 2).

3.2. Interviews with Witnesses of MMS Sightings

During the present research, we were able to collect information relative to 11 sightings, concentrated from 2009 to 2014, obtained through direct interviews with the witnesses of the encounters (methodology B). Seven sightings were considered reliable, and four were deemed unreliable. These data were verified through the coherency of the answers to the interview protocol. All of the sightings represent incidental encounters by locals and tourists that have observed seals (Table 3 and Figure 2a).

Table 3.

Recent sightings (after 2000) of the Mediterranean monk seal in Salento. Organized by Year, Month, and number of individuals per sighting (N).

Figure 2.

Locations of Mediterranean monk seal sightings in Salento. In (a), the locations of recent sightings (after 2000) are represented by circles. In (b), the locations of historical sightings (before 2000) are represented by squares.

3.3. Compilation of Historical Presence

The bibliographical research allowed for the recording of historical data (before 2000), with specific information referring at least to the year and the location of the monk seal presence along the examined coast for the period 1853 to 1988 over 135 years. Chronologically, we found one piece of information from 1853 and another from 1915; between 1915 and 1956, the longest gap in the time series was recorded. Within this gap, anecdotal information on the local presence (rare) of the species was recovered but without sufficient information to make the data comparable with the rest of the dataset. However, we deemed it appropriate to consider this information when discussing the data collected in the present study. Excluding the first two data (referring to 1853 and 1915), most of the sightings collected were concentrated in the period from 1956 to 1988, covering a time frame of 33 years. The investigation of animal remains (skulls, skin, and stuffed specimens) and photographs preserved in institutions, museums, and private collections (Figure 3) confirmed five records recovered from the bibliographical survey: 1853 close to Gallipoli, 1915 in Otranto, September 1964 in Castro, August 1965 in Gallipoli, and 7 August 1973 in Gagliano (Table 4 and Figure 2b and Figure 3a,b). The only information collected during the present research for which there was no bibliographical record is the photography of the skin of an animal found dead, entangled in a net north of Castro on April 1965 (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

(a) Stuffed individual captured in Otranto in 1915; (b) the skull of the seal captured in Gallipoli, and (b) the skin of the one entangled in a net in Castro in 1965 (photo credits: (a,b) Luigi Bundone, (c) courtesy of Mario Molendini).

Table 4.

Mediterranean monk seal historical sightings (before 2000) in Salento. Organized by Year, Period, number of individuals per sighting (N), and Main Location.

3.4. Combining the Methodologies

The set of data referring to recent (from 2000 onward) MMS sightings, combining the information obtained from methodology A and B, are represented in Table 3 and Figure 2a. The dataset includes the 2003 previously reported data, the seven sightings recorded and validated through the direct interview with the witness (methodology B), and the three sightings recorded through the questionnaire to fishermen (methodology A). Only in one case was the presence of more than one animal reported (November 2013). All the sightings were reported from the eastern Salento coast, except the one near Santa Caterina (west coast).

The sets of data referring to the historical MMS presence (before 2000), recovered from methodologies A and C, were combined together to obtain a complete frame of the available information and are shown in Table 4 and Figure 2b. In three cases, through the interviews with the fishermen, we confirmed the information extracted from the literature in 1968, in 1973 in Ugento, and in 1973 along the coast of Gagliano. Only one data previously unreported was collected during the present research: the sighting in Leuca in 1978.

The presence of several individuals in the study area was underlined by sightings of dead animals: in 1964 and in 1965 in Castro, in 1965 in Gallipoli, in 1970 and 1976 in the area of Gagliano, and in 1971 in the area of Tricase; only one concerned a live animal, in 1958 near Tricase, related to the presence of three individuals at the same time.

The complete set of historical (30) and recent (11) sightings, collected using the three different methodologies, were compared with reporting on the sightings in SSEs (Figure 4); the plot of the data, organized into 5-year-period bands from 1850 to 2015, showed two peaks of six SSEs in the period 1976–1980 and 2011–2015. Most of the data are concentrated from 1956 to 2015, showing a complete lack of SSEs in the bands between 1856–1910, 1916–1955, and 1991–2000.

Figure 4.

Distribution of historical and recent Mediterranean monk seal sightings in Salento. The sightings are organized into Single Sighting Events (SSE = unit, regardless of the number of individuals sighted simultaneously) and sorted in bands of 5 years.

4. Discussion

The present research represents a new and preliminary step to shed light on a poorly explored area of the status of MMS, potentially linked to the well-known monk seal reproductive sub-population from the Greek Ionian Island [9,12,40,81,82,83,84,85], by using combined appropriate research methodologies (questionnaire with fishermen, interviews with witnesses of sightings, and compilation of historical presence). To our knowledge, this is the first time that three different methodologies, such as these, are combined to investigate the historical and present information of an endangered species such as the Mediterranean monk seal. However, combining multiple methods to investigate the occurrence of this species was, more recently, also followed by Pietroluongo et al. [38]. This demonstrates that, similar to our study, an integrated approach can effectively increase the data and supports filling knowledge gaps on the matter.

Questionnaire surveys with artisanal fishermen have already been used to evaluate MMS abundance [15] and interactions between MMS and small-scale fisheries [62,63,86,87] in areas where reproductive sub-populations of the species occur. Following the examples carried out along the coast of Morocco and Syria [56,57,58,59,60], we designed and tested a questionnaire (methodology A) as a new tool to evaluate monk seal sightings in LDAs, where no reproductive sub-populations are known or presumed to survive and to monitor efforts on the species are lacking, but where seals can reasonably still be present (i.e., in consideration of the close distance to known reproductive sub-populations, report of occasional sightings, etc.). Salento was selected as the area to apply the questionnaire to fishermen; however, it could be an efficient tool for other monk seals’ LDAs to increase information about this endangered species.

The analysis of the bibliographic materials highlighted that the MMS had frequented the coast of Salento since the Palaeolithic [51,88,89,90,91]. The presence of the MMSs was confirmed in different texts [50,91], reporting a relatively low abundance of the species already between the 17th and 19th centuries [52,73]. A similar condition has been described concerning the period between the 1940s and 1970s [52,53,54,71,92], when the species, regarded as rare, was reported to be occasionally encountered along circumscribed areas of the Salento coast. Since the above pieces of information were not supported with specific references to allow a comparison with the rest of the data, they were not considered in the dataset analysis. Most of the historical data (before 2000) on monk seal presence, retrieved and analysed, were concentrated between 1956 and 1988, and suggest discontinuous occurrence in the area. Moreover, only two of the recent sightings (from 2000 onward) were directly reported to official entities (e.g., Port Authority), one in 2003 and one in 2014; all the other information was unveiled during our research activities, referring to the years 2009, 2010, 2013, and 2014. The results plotting historical (before 2000) and recent (from 2000 onward) sightings suggest that, though not abundant, the species’ frequentation of the coast never ceased. The lack of information about its presence might, instead, reflect a shortage of sampling efforts. It is understood that population numbers cannot be provided simply by assessing the sightings. However, the data concerning sightings can be regarded as a clear sign of presence, especially if repeated over time. In contrast, the lack of sightings does not necessarily imply the absence or extinction of the species.

The absence of data rather reflects the lack of constant systematic monitoring efforts to establish the presence and the eventual reproduction of the species in areas where the situation is presently unknown. This has been outlined in the document by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean [33] referring to the elusive behaviour of the MMS. The integration of recent MMS sightings data and historical information was useful for understanding the local trend of the sightings and conservation priorities for the species and its habitat, as was suggested by McClenachan et al. [21] for other species. In only one case related to the recent sightings, the information collected might provide useful data on the seal habitat in the area (November 2014, North of Castro) since the seal was spotted while emerging from the entrance of a marine coastal cave. The still active frequentation of the Salento coast by MMS specimens was also corroborated by additional up-to-date sightings: one close to Tricase in June 2017 recorded on video [93] and one young animal in 2020 along the northeastern coast of Salento (Unpublished data, co-shared with ISPRA-Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale) that died after a few days slightly further north in the province of Brindisi [94]. It is worth mentioning that the genetic analysis that followed the necropsy of the above-mentioned young seal [95] revealed that the haplotype of the specimen belonged to the same gene pool of the Greek Ionian Sea MMS sub-population [95,96,97]. Additional sightings were also reported in 2020, 2021, and 2022 (Unpublished data, co-shared with ISPRA), in some cases supported with video/photographic documentation. Recent eDNA studies seem to confirm the frequentation of the area by seal individuals [98].

In this framework, we cannot completely exclude that the recent sightings might depend on the slight increment of the overall population of the MMS recorded elsewhere [8], which possibly has pushed individuals to spread out in search of new areas. Population recoveries and natural re-colonization might occur within the Mediterranean Sea as is happening in other areas and with other species. Due to conservation activities put into practice locally, the sub-population of MMS in Cabo Blanco (Mauritania/Western Sahara) has shown good resilience following the mass die-off of 1997 [99,100]. The northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustrirostris, Gill 1866), another representative of the tribe Monachini, reduced to near extinction in the late nineteenth century, has shown even higher population recovery, reaching high enough numbers to re-colonize the coasts up to ~1.300 km northward [101].

A current overview of the MMS presence in the Adriatic–Ionian region contextualizes MMS monitoring and protection on the need for a wide-region conservation approach [102]. MMSs are able to move for great distances [103], even over open water [104,105]. Our recent data need to be taken with the sightings reported over the same period from Croatia, Montenegro, and Albania [29,69,106,107,108,109] and the known breeding sub-population in the Greek Ionian Islands, e.g., [12,18,85].

The result of the interviews with fishermen showed that this stakeholder group is well disposed to be included in the management and protection of natural resources. Fishermen are more sensitive than others to economic advantages resulting from collaborations, in particular, with MPAs. Where artisanal fishermen have benefited from subsidies for damage to the nets and the catch caused by dolphins (e.g., bottlenose dolphins), they have proved the tendency to overestimate the extent of that damage and exceed the actual number of animals [110]. In our case, approximately half of the interviewees were favourable to the establishment of protected areas and no fishing seasons as measures for the recovery of fish stocks. Such propensity might be encouraged by the positive experience of the neighbouring MPA of Torre Guaceto [24,111], ~50 km north of San Cataldo, along the Adriatic coast of Apulia. The majority of fishermen interviewed belonged to the small fishermen communities working along the South and Eastern Salento coasts. The reluctance of some concerning the no-fishing season was related to a lack of reimbursements, inappropriate protection measures (e.g., mistaking fish’s reproductive periods), and lack of restrictions to other fishing categories (e.g., recreational fishery). Artisanal fishery is going through a decline, considering the decrease in new licenses and the progressive reduction of fishing activities [112]. Indeed, our results are aligned with this trend, having recorded the high average age of the fishermen interviewed. The lack of generational recruitment is probably due to fish resources and earnings scarcity [113] and, from a more general perspective, the lack of effective and enduring political actions [114]. Fishermen’s involvement and long-term protection policies are essential to achieve effective conservation results, as is shown by the MMS individuals that began to re-use the coast of Madeira from the nearby Desertas Islands (~130 km to the southeast) [115,116]. This is the outcome of the extensive conservation efforts performed with the involvement of local fishermen during the last 30 years in the natural park [63].

Our results showed the need to undertake detailed studies on the MMS and the implementation of appropriate conservation measures in LDAs. Salento could be a geographically suitable site as an ecological corridor, where thoughtful practices of marine spatial planning and coastal protection aimed at the conservation of the MMS should be implemented. Additionally, aiding the recovery of species at high-level trophic positions, such as the monk seal, might lead to the long-term restoration of coastal ecosystems [117].

The present work followed a region-wide approach reviewing the status of the species along the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. A region-wide approach was recently recommended for the conservation of the species, considering the possibility of individuals moving over the waters of national territorial boundaries [29,102]. It must include areas where (i) the presence of the species is ascertained, (ii) individuals may migrate or disperse, and (iii) the species is assumed to be present, but data, conservation plans, and monitoring activities are currently lacking [30]. Monitoring efforts and protection measures for the MMS and its habitat need to be strengthened, not only on a local scale but within a broad regional framework. These might favour the species’ recovery in its former habitat (natural re-colonization), ensure the movement of the individuals, and potentially improve the status of the marine ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d15060740/s1, File S1, Text of the questionnaire to fishermen, and File S2, Distribution of the fishing vessels according to the fishing districts and ports in Salento.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B. and E.M.; methodology, L.B. and E.M.; validation, L.B., E.M. and S.G.; formal analysis, L.B., E.M. and S.G.; investigation, L.B., S.F. and L.R.; data curation, L.B., E.M. and S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B., E.M., S.G., L.R. and G.H.-M.; writing—review and editing, L.B., E.M., S.G., L.R. and G.H.-M.; visualization, L.B., E.M., S.G., L.R. and G.H.-M.; supervision, L.B., E.M. and S.G.; project administration, L.B. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No animal testing was performed during this study.

Informed Consent Statement

All necessary permits for sampling and observational field studies have been obtained by the authors from the competent authorities and are mentioned in the acknowledgments if applicable. The interviews are in accordance with European procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The present research was possible thanks to the contribution of several people. In particular, we would like to thank Bruna De Marchi for the invaluable guidance when “building” the questionnaire for fishermen and for suggestions on how to organize and analyse the data. The collection of sightings was encouraged by the support of very motivated and passionate “of the well-being of their territory” locals and other kindly available researchers: (Super) Mario Congedo, Raffaele Onorato, Cataldo Lichelli, Mario Molendini, Roberto Basso, Carmela Caroppo, Ovidio Picariello, Paolo Forti, Giacomo Marzano, and Luigi Ruberto. In addition, we would like to express our gratitude to the following institutions and organizations: Archipelagos-environment and Development, University of Salento, Marine Protected Area Porto Cesareo, Parco Naturale Regionale Costa Otranto-Santa Maria di Leuca e Bosco di Tricase, “Corpo Forestale, Presidio San Cataldo (Lecce)”, Real Museo Zoologico del Centro Musei delle S.N.F. dell’Università di Napoli Federico II, Museo Civico di Jesolo, Magna Grecia Mare, Cuppula Tisa, Liceo Palmieri (Lecce), and all the stakeholders that helped in building a strong information network for monk seal sightings along the coast of Salento. Finally, we are grateful to Francesco Nepitello, Barbara, and Charlie Putnam for the revision of the English language.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- González, L.M. Prehistoric and historic distributions of the critically endangered Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) in the eastern Atlantic. Mar. Mam. Sci. 2015, 3, 1168–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Kotomatas, S. Are Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus, being left to save themselves from extinction? Adv. Mar. Biol. 2016, 75, 359–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W.M.; Lavigne, D.M. Monk Seals in Antiquity. The Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus) in Ancient History and Literature; Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.M. Monk Seals in Post-Classical History. The Role of the Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus) in European History and Culture, from the Fall of Rome to the 20th Century; Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Israëls, L.D.E. Thirty Years of Mediterranean Monk Seal Protection, a Review; Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Androukaki, E.; Adamantopoulou, S.; Dendrinos, P.; Tounta, E.; Kotomatas, S. Causes of death in the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) in Greece. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Monaco, 20–24 January 1998; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Androukaki, E.; Adamantopoulou, S.; Dendrinos, P.; Tounta, E.; Kotomatas, S. Causes of mortality in the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) in Greece. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions, Athens, Greece, 1–5 April 1996; pp. 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Dendrinos, P.; Fernández De Larrinoa, P.; Güçü, A.C.; Johnson, W.M.; Kiraç, C.O.; Pires, R. The Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus: Status, biology, threats, and conservation priorities. Mammal. Rev. 2016, 46, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Jacobs, J.; Panos, D. The endangered Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus in the Ionian Sea, Greece. Biol. Conserv. 1993, 64, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Androukaki, E.; Adamantopouplou, S.; Chatzispyrou, A.; Johnson, W.M.; Kotomatas, S.; Papapdopoulos, A.; Paravas, V.; Paximadis, G.; Pires, R.; et al. Assessing accidental entanglement as a threat to the Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus. Endanger. Species Res. 2008, 5, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaks, K.M.; Aguilar, A.; Aurioles, D.; Burkanov, V.; Campagna, C.; Gales, N.; Gelatt, T.; Goldsworthy, S.D.; Goodman, S.J.; Hofmeyr, G.J.G.; et al. Global threats to pinnipeds. Mar. Mam. Sci. 2012, 28, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.; Panou, A. Conservation of the Mediterranean Monk Seal, Monachus monachus, in Kefalonia, Ithaca and Lefkada Islands, Ionian Sea, Greece; Institute of Zoology, University of Munich: Munich, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Neis, B.; Schneider, D.C.; Felt, L.; Haedrich, R.L.; Fischer, J.; Hutchings, J.A. Fisheries assessment: What can be learned from interviewing resource users? Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1999, 56, 1949–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Tselentis, L.; Voutsinas, N.; Mourelatos, C.H.; Kaloupi, S.; Voutsinas, V.; Moschonas, S. Incidental catches of marine turtles in surface long line fishery in the Ionian Sea, Greece. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions, Athens, Greece, 1–5 April 1996; pp. 435–445. [Google Scholar]

- Panou, A.; Alimantiri, L.; Aravantinos, P.; Verriopoulos, G. Distribution of the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) in Greece: Results of a Pan-Hellenic questionnaire action, 1982–1991. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions, Athens, Greece, 1–5 April 1996; pp. 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Pirounakis, K.; Moschonas, S.; Tselentis, L.; Voutsinas, N.; Mourelatos, Y.; Kaloupi, S.; Voutsinas, V.; Panou, A. Cetaceans in the Ionian Sea: Results of an observers’ network. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions, Athens, Greece, 1–5 April 1996; pp. 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, R.E.; Freeman, M.M.R.; Hamilton, R.J. Ignore fishers’ knowledge and miss the boat. Fish Fish. 2000, 1, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A. Monk seal sightings in the central Ionian Sea. A network of fishermen for the protection of the marine resources. Who are our seals? In Proceedings of the Workshop within the Framework of the 23rd Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Istanbul, Turkey, 28 February 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.E.; Cox, T.M.; Lewison, R.L.; Read, A.J.; Bjorkland, R.; McDonald, S.L.; Crowder, L.B.; Aruna, E.; Ayissi, I.; Espeut, P.; et al. An interview-based approach to assess marine mammal and sea turtle captures in artisanal fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynou, F.; Sbrana, M.; Sartor, P.; Maravelias, C.; Kavadas, S.; Damalas, D.; Cartes, J.E.; Osio, G. Estimating trends of population decline in long-lived marine species in the Mediterranean Sea based on fishers’ perceptions. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClenachan, L.; Ferretti, F.; Baum, J.K. From archives to conservation: Why historical data are needed to set baselines for marine animals and ecosystems. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalvo, J.; Giovos, I.; Moutopoulos, D.K. Fishermen’s perception on the sustainability of small-scale fisheries and dolphin-fisheries interactions in two increasingly fragile coastal ecosystems in western Greece. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2015, 25, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, P.; Claudet, J. Comanagement practices enhance fisheries in Marine Protected Areas. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 24, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidetti, P.; Bussotti, S.; Pizzolante, F.; Ciccolella, A. Assessing the potential of an artisanal fishing co-management in the Marine Protected Area of Torre Guaceto (southern Adriatic Sea, SE Italy). Fish. Res. 2010, 101, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, A.; Bodilis, P.; Piante, C.; Di Carlo, G.; Thiriet, P.; Francour, P.; Guidetti, P. Fishermen Engagement, a Key Element to the Success of Artisanal Fisheries Management in Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas; WWF France: Port-Cros, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugio, H.; Oliver, P.; Biagi, F. An overview of the history, knowledge, recent and future research trends in Mediterranean Fisheries. Sci. Mar. 1993, 57, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Pipitone, C.; Badalamenti, F.; Vega-Fenández, T.; D’Anna, G. Spatial management of fisheries in the Mediterranean Sea: Problematic issues and a few success stories. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2014, 69, 371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Adamantopoulou, S.; Tounta, E.; Dendrinos, P. Monachus monachus (Eastern Mediterranean subpopulation). IUCN Red List. Threat. Species 2019, e.T120868935A120869697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundone, L.; Panou, A.; Molinaroli, E. On sightings of (vagrants?) monk seals, Monachus monachus, in the Mediterranean Basin and their importance for the conservation of the species. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-MAP/RAC-SPA. The conservation of the Mediterranean monk seal: Proposal of Priority activities to be carried out in the Mediterranean Sea. In Proceedings of the Sixth Meeting of National Focal Points for SPAs, Marseilles, France, 17–20 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-MAP/RAC-SPA. Regional Strategy for the Conservation of the Monk Seals in the Mediterranean (2014–2019); UNEP-MAP–RAC/SPA: Tunis, Tunisia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Conservation and recovery of the Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus. In Resolution 4.023 in Resolutions and Recommendations, Proceedings of the 4th IUCN World Conservation Congress, Barcelona, Spain, 5–14 October 2008; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- GFCM. Draft Summary of Information on Monk Seals in the Mediterranean and Black Sea; FAO: Rome, Italy; General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, S.; Foote, A.D.; Kötter, S.; Harries, O.; Mandleberg, L.; Stevick, P.T.; Whooley, P.; Durban, J.W. Using opportunistic photo-identifications to detect a population decline of false killer whales (Orcinus orca) in British and Irish waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2014, 94, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, L.; Tardin, R. Citizen science contributes to the understanding of the occurrence and distribution of cetaceans in southern Brasil. A case study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 158, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matear, L.; Robbins, J.R.; Hale, M.; Potts, J. Cetacean biodiversity in the Bay of Biscay: Suggestions for environmental protection derived from citizen science data. Mar. Policy 2019, 109, 103672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.; Robinson, S.; Littnan, C. Social media as a data resource for #monkseal conservation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222627. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroluongo, G.; Martín-Montalvo, B.Q.; Ashok, K.; Miliou, A.; Fosberry, J.; Antichi, S.; Moscatelli, S.; Tsimpidis, T.; Carlucci, R.; Azzolin, M. Combining monitoring approaches as a tool to asess the occurrence of the Mediterranean monk seal in Samos Island, Greece. Hydrobiology 2022, 1, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devictor, V.; Whittaker, R.J.; Beltrame, C. Beyond scarcity: Citizen science programmes as useful tools for conservation biogeography. Divers. Distrib. 2010, 16, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Aravantinos, P.; Kokkolis, T.; Kourkoulakos, S.; Lekatsa, T.; Minetou, T.; Panos, D.; Pirounakis, K.; Scalvos, E. The Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus, in the Central Ionian Sea, Greece: Results of a long-term study. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions, Thessaloniki, Greece, 22–22 May 2002; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, A. Current status of Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) populations. In Proceedings of the Experts on the Implementation of the Action Plans for Marine Mammals (Monk Seal and Cetaceans) Adopted within MAP, Arta, Greece, 29–31 October 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, G.; Agnesi, S.; Di Nora, T.; Tunesi, L. Mediterranean monk seal sightings in Italy through interviews: Validating the information (1998–2006). Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer. Médit. 2007, 38, 542. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, G. Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) sightings in Italy (1998–2010) and implications for conservation. Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinini, C.; Battistoni, A.; Peronace, V.; Teofili, C. Lista Rossa IUCN dei Vertebrati Italiani; Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rondinini, C.; Battistoni, A.; Teofili, C. Lista Rossa IUCN dei Vertebrati Italiani; Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baisre, J.A. Shifting baselines and the extinction of the Caribbean monk seal. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 27, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, C.; Vieira, N. Using historical accounts to assess the occurrence and distribution of small cetaceans in a poorly known area. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2010, 90, 1583–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotze, H.K.; Erlandson, J.M.; Hardt, M.J.; Norris, R.D.; Roy, K.; Smith, T.D.; Withcraft, C.R. Uncovering the ocean’s past. In Shifting Baselines: The Past and Future of Ocean Fisheries; Jackson, J.B.C., Alexander, K.E., Sala, E., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 137–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tingley, M.W.; Beissinger, S.R. Detecting range shifts from historical species occurrences: New perspectives on old data. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferraris, A. De Situ Iapygiae; Petrum Pernam: Basilea, Swiss, 1558. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, G.A. Grotta Romanelli I. Stratigrafia dei Depositi e Origine di Essi; Stab. Grafico Commerciale: Florence, Italy, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, S. Considerazioni sulla foca monaca mediterranea. Storia, distribuzione e stato di Monachus monachus (Hermann 1779) nel Mare Adriatico (Mammalia, Pinnipedia, Phocidae). Scritti in memoria di Augusto Toschi, supplemento alle. Ric. Di Biol. Della Selvag. 1976, 7, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Parenzan, P. Puglia Marittima Vol.1; Congedo Editore: Galatina, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dantoni, G.; Onorato, R. L’acqua Scolpì un Cielo di Pietra. Portoselvaggio, Preistoria e Speleologia; Conte Editore: Lecce, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, I.L.; Stanfield, M.P. Circumstantial evidence for the presence of monk seals in the West Indies. Oryx 1998, 32, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, G.; Gazo, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Ammar, I.; Ghanem, W. Monk seal presence and habitat assessment. Results of a preliminary mission carried out in Syria. Monachus Guard. 2003, 6, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, G.; Bazairi, H.; Tunesi, L.; Sadki, I. Results of a first field mission in the National Park of Al Hoceima, Morocco: Monk seal habitat suitability and presence. Monachus Guard. 2003, 6, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, G.; Bazairi, H.; Salvati, E.; Agnesi, S.; Limam, A.; Nachite, L.D.; Rais, C.; Sadki, I.; Tunesi, L.; Zine, N. Habitat suitability and sightings of the Mediterranean monk seal in the National Park of Al Hoceima (Morocco). Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer. Medit. 2004, 37, 538. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, G.; Bazairi, H.; Bayed, A.; Agnesi, S. Survey on Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) sightings in Mediterranean Morocco. Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Mo, G.; Tayeb, K. Results of a preliminary mission carried out in Cyrenaica, Libya, to assess monk seal presence and potential coastal habitat. Monachus Guard. 2003, 6, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bearzi, G. Interactions between Cetacean and Fisheries in the Mediterranean Sea; ACCOBAMS Secretariat: Monaco, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Glain, D.; Kotomatas, S.; Adamantopoulou, S. Fishermen and seal conservation: Survey of attitudes towards monk seals in Greece and grey seals in Cornwall. Mammalia 2001, 65, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.; Pires, R.; Santos, P.; Karamanlidis, A.A. Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus): Fishery interactions in the Archipelago of Madeira. Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, B.; Dede, A. Present status of the Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779) on the coast of Foça in the bay of Izmir (Aegean Sea). Turkish J. Mar. Sci. 1995, 1, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, I.H.; Skourtos, M.S.; Kontogianni, A.; Day, R.J.; Georgiou, S.; Bateman, I.J. Use and nonuse values for conserving endangered species: The case of the Mediterranean monk seal. Environ. Plann. A 2001, 33, 2219–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, Z.S.; Dikou, A. Integrating conservation and development at the National Marine Park of Alonissos, Northern Sporades, Greece: Perception and practice. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stithou, M.; Scarpa, R. Collective versus voluntary payment in contingent valuation for the conservation of marine biodiversity: An exploratory study from Zakynthos, Greece. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2011, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivourea, M.N.; Karamanlidis, A.A.; Tounta, E.; Dendrinos, P.; Kotomatas, S. People and the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus): A study of the socioeconomic impacts of the National Marine Park of Alonissos, Northern Sporades, Greece. Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Varda, D.; Bundone, L. The Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus, in Montenegro. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium of Ecologists, Sutomore, Montenegro, 4–7 October 2017; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, R. Un mare per le “monache”. In I Parchi Marini, Realizzazione e Gestione; Atti della tavola rotonda: Firenze, Italy, 1989; pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Congedo, R. Che Cosa Vuole il Fondo Mondiale della Natura? Editrice Salentina-Galatina: Lecce, Italy, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Cornaglia, E. Foca Bianca nel Salento. Anim. E Nat. 1974, 4, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, G. Fauna Salentina Ossia Enumerazione di Tutti Gli Animali Che Trovansi Nelle Diverse Contrade della Provincia di Terra d’Otranto e Nelle Acque de’ Due Mari Che la Bagnano; Tipografia Editrice Salentina: Lecce, Italy, 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Di Turo, P. Il Problema Della Foca Monaca (Monachus monachus) in Puglia. Master Thesis, Università degli Studi di Lecce Facoltà di Scienze Corso di Scienze Biologiche, Lecce, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Di Turo, P. Presenza della foca monaca (Monachus monachus) nell’area mediterranea con particolare riferimento alla Puglia. Thalass. Salentina 1984, 14, 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Forti, P. I risultati delle esplorazioni speleosubacquee condotte dall’U.S.B. in Puglia nell’anno 1973. In Proceedings of the Atti del 1° Convegno Regionale di Speleologia, Castellana Grotte, Bari, Italy, 6–7 June 1981; pp. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco, A.; Giangreco, G. Campagna di ricerca speleologica nella zona del “Ciolo”, Gagliano del Capo (Lecce). La Zagaglia 1973, 59, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Maio, N.; Picariello, O. I Pinnipedi e Sirenii del Museo Zoologico dell’Università di Napoli Federico II (Mammalia:Carnivora, Sirenia). Catalogo della collezione con note storiche e osteometriche. Atti. Soc. It Sci. Nat. Museo Civ. Stor. Nat. Milano 2000, 141, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mastragostino, L.S.O.S. Foca monaca. Pesca Mare 1989, 5, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.; Ruggiero, L. Collezioni Scientifiche a Lecce. Memorie Dimenticate di Un’intensa Stagione Culturale; Edizioni del Grifo: Lecce, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bundone, L.; Panou, A. Improvement of knowledge on the Mediterranean monk seal sub-population in the central Ionian Sea, Greece, using photo-identification. In Proceedings of the Abstract Book of the 33rd Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Ashdod, Israel, 5–7 April 2022; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Panou, A.; Bundone, L.; Aravantinos, P. Mediterranean monk seal habitat use in the Central Ionian, Greece. In Proceedings of the Abstract Book of the World Marine Mammal Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 7–12 December 2019; p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- Bundone, L.; Panou, A.; Aravantinos, P.; Muñoz-Cañas, M. Photo-identification of the Mediterranean monk seal sub-population in the central Ionian Sea, Greece. In Proceedings of the Abstract Book of the World Marine Mammal Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 7–12 December 2019; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Panou, A.; Bundone, L.; Aravantinos, P.; Kokkolis, T.; Chaldas, X. Mediterranean monk seal, a sign of hope: Increased birth numbers and enlarged terrestrial habitat. In Proceedings of the Abstract Book of the 33rd Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Ashdod, Israel, 5–7 April 2022; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Panou, A.; Bundone, L.; Aravantinos, P.; Kokkolis, T. Mediterranean monk seal monitoring in the central Ionian Sea, Greece-35 Years of Studies. In Proceedings of the Abstract Book of the 24th Biennial Conferences on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Palm Beach, FL, USA, 1–5 August 2022; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Güçlüsoy, H. Interaction between Monk Seals, Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779), and artisanal fisheries in the Foça Pilot Monk Seal Conservation Area, Turkey. Zool. Middle East 2008, 43, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Adamantopoulou, S.; Kallianiotis, A.A.; Tounta, E.; Dendrinos, P. An interview-based approach assessing interaction between seals and small-scale fisheries informs the conservation strategy of the endangered Mediterranean monk seal. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2020, 30, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussi, M. II Paleolitico e il Mesolitico in Italia. Popoli e Civiltà dell’Italia Antica, Biblioteca di Storia Patria; STILUS BSP Editrice s.r.l.: Bologna, Italy, 1992; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Cassoli, P.F.; Tagliacozzo, A. Butchering and cooking of birds in the Palaeolithic site of Grotta Romanelli (Italy). Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 1997, 7, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serangeli, J. La zona de costa en Europa durante la última glaciación. Consideraciones al análisis de restos y representaciones de focas, cetáceos y alcas gigantes. Cypsela 2001, 13, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Marciano, G. Descrizione, Origine e Successi della Provincia d’Otranto; Stamperia dell’Iride: Naples, Italy, 1855. [Google Scholar]

- Onorato, R.; Denitto, F.; Belmonte, G. Le grotte marine del Salento: Classificazione, localizzazione e descrizione. Thalass. Salentina 1999, 23, 67–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bundone, L.; Fai, S.; Molinaroli, E. First video documented presence of Mediterranean monk seal in Southern Apulia (Italy). In Proceedings of the Abstract Book of the 32nd Conference of the European Cetacean Society, La Spezia, Italy, 6–10 April 2018; p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- Petrella, A.; Mazzariol, S.; Padalino, I.; Di Francesco, G.; Casalone, C.; Grattarola, C.; Di Guardo, G.; Smoglica, C.; Centelleghe, C.; Gili, C. Cetacean morbillivirus and Toxoplasma gondii co-infection in Mediterranean monk seal pup, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1237–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioravanti, T.; Splendiani, A.; Righi, T.; Maio, N.; Lo Brutto, S.; Petrella, A.; Caputo Barucchi, V. A Mediterranean monk seal pup on the Apulian coast (Southern Italy): Sign of an ongoing recolonization? Diversity 2020, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Gaughran, S.; Aguilar, A.; Dendrinos, P.; Huber, D.; Pires, R.; Schultz, J.; Skrbinšek, T.; Amato, J. Shaping species conservation strategies using mtDNA analysis: The case of the elusive Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus). Biol. Conserv. 2016, 139, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubert, P.; Justy, F.; Mo, G.; Aguilar, A.; Danyer, E.; Borrell, A.; Dendrinos, P.; Öztürk, B.; Improta, R.; Tonay, A.M.; et al. Insight from 180 years of mitochondrial variability in the endangered Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus). Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2019, 35, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, E.; Tavecchia, G.; Boldrocchi, G.; Coppola, E.; Ramella, D.; Conte, L.; Blasi, M.; Galli, P. Playing “hide and seek” with the Mediterranean monk seal: A citizen science dataset reveals its distribution from molecular traces (eDNA). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jaregui, M.; Tavecchia, G.; Cedenilla, M.A.; Coulson, T.; Fernández de Larinnoa, P.; Muñoz, M.; González, L.M. Population resilience of the Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus at Cabo Blanco peninsula. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 461, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cañas, M.; Haya, M.; M’Bareck, A.; Aparicio, F.; Cedenilla, M.A.; M’Bareck, H.; Fernández de Larrinoa, P. Observatory of the Mediterranean monk seal population of the Cabo Blanco peninsula (Mauritania/Morocco). An important conservation tool. In Proceedings of the Abstracts Book of the 30th Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Funchal, Madeira, 14–16 March 2016; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzel, A.R.; Fleischer, R.C.; Campagna, C.; Le Boeuf, B.J.; Alvord, G. Impact of a population bottleneck on symmetry and genetic diversity in the northern elephant seal. J. Evol. Biol. 2002, 15, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Giannoulaki, M.; Varda, D.; Lazaj, L.; Pojana, G.; Bundone, L. Towards a strategy for the recovering of the Mediterranean monk seal in the Adriatic-Ionian Basin. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1034124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamantopoulou, S.; Androukaki, E.; Dendrinos, P.; Kotomatas, S.; Paravas, V.; Psaradellis, M.; Tounta, E.; Karamanlidis, A.A. Movements of Mediterranean monk seals (Monachus monachus) in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Cucknell, A.C.; Romagosa, M.; Boisseau, O.; Moscrop, A.; Frantzis, A.; McLanaghan, R. A Visual and Acoustic Survey for Marine Mammals in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea during Summer 2013; International Fund for Animal Welfare, Marine Conservation Research International: Kelvedon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roditi-Elasar, M.; Bundone, L.; Goffman, O.; Scheinin, A.P.; Kerem, D.H. Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) sightings in Israel 2009–2020: Extralimital records or signs of population expansion? Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2021, 7, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundone, L.; Antolovic, J.; Coppola, E.; Zalac, S.; Hervat, M.; Antolovic, N.; Molinaroli, E. Habitat use, movement and sightings of monk seals in Croatia between 2010 and 2012–2013. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer. Médit. 2013, 40, 608. [Google Scholar]

- Bundone, L.; Panou, A.; Kokkolis, T.; Aravantinos, P.; Hysolakoj, N.; Mehillaj, T.; Bakiu, R. Coordinated monitoring of the Mediterranean monk seal among MPAs in the Adriatic-Ionian macro-region. In Proceedings of the Workshop, Managing Highly Mobile Species across Mediterranean MPAs, MedPAN Network Regional Experience-Sharing, Akyaka, Turkey, 11–14 November 2019; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Bundone, L.; Hernandez-Milian, G.; Hysolakoj, N.; Bakiu, R.; Mehillaj, T.; Lazaj, L. Mediterranean monk seal in Albania: Historical presence, sightings and habitat availability. JNTS 2021, 53, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bundone, L.; Hernandez-Milian, G.; Hysolakoj, N.; Bakiu, R.; Mehillaj, T.; Lazaj, L.; Deng, H.; Lusher, A.; Pojana, G. First documented uses of caves along the coast of Albania by Mediterranean monk seals (Monachus monachus, Hermann 1779): Ecological and conservation inferences. Animals 2022, 12, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearzi, G.; Bonizzoni, S.; Gonzalvo, J. Dolphins and coastal fisheries within a marine protected area: Mismatch between dolphin occurrence and reported depredation. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2011, 21, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, A.; Coppini, G.; Pujolar, J.M.; De Leo, G.A.; Gatto, M.; Lyubartev, V.; Meliá, P.; Zane, L.; Guidetti, P. Assessing dispersal patterns of fish propagules from an effective Mediterranean marine protected area. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, J.; Cowx, I.G.; Cabral, H.; Castro, M.; Font, T.; Gonçalves, J.M.S.; Gordoa, A.; Hoefnagel, E.; Matić-Skoko, S.; Mikkelsen, E.; et al. Small-scale coastal fisheries in European Seas are not what they were: Ecological, social and economic changes. Mar. Policy 2016, 98, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Maiorano, P.; Sion, L.; D’Onghia, G. Fishery resources: Between ecology and economy. Rend. Lincei 2015, 26, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, T.; Gray, T. Fisheries science and sustainability in international policy: A study of failure in the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy. Mar. Policy 2005, 29, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, R. Are monk seals recolonising Madeira Island? Monachus Guard. 2001, 4, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanlidis, A.A.; Pires, R.; Neves, H.C.; Santos, C. Homeward bound: Are monk seals returning to Madeira’s Sao Lourenço peninsula? Monachus Guard. 2002, 5, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Prato, G.; Guidetti, P.; Bartolini, F.; Mangialajo, L.; Francour, P. The importance of high-level predators in marine protected area management: Consequences of their decline and their potential recovery in the Mediterranean context. Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 2013, 4, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).