Forest Disturbances Threatening Cypripedium calceolus Populations Can Improve Its Habitat Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Species

2.2. Study Sites

2.3. Natura 2000 Habitats

2.4. Historical Land Cover

2.5. Bark Beetle Infestation Risk

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

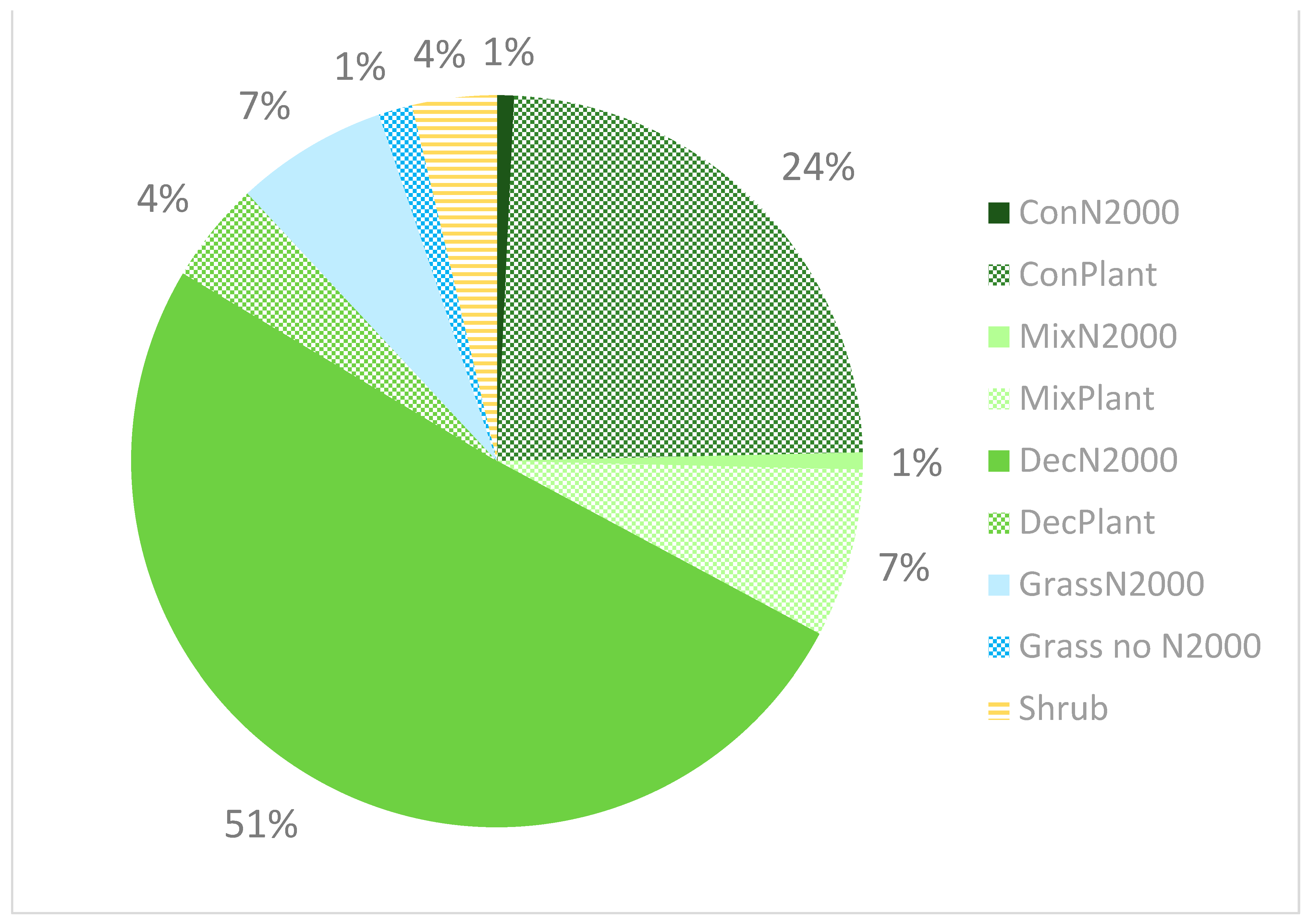

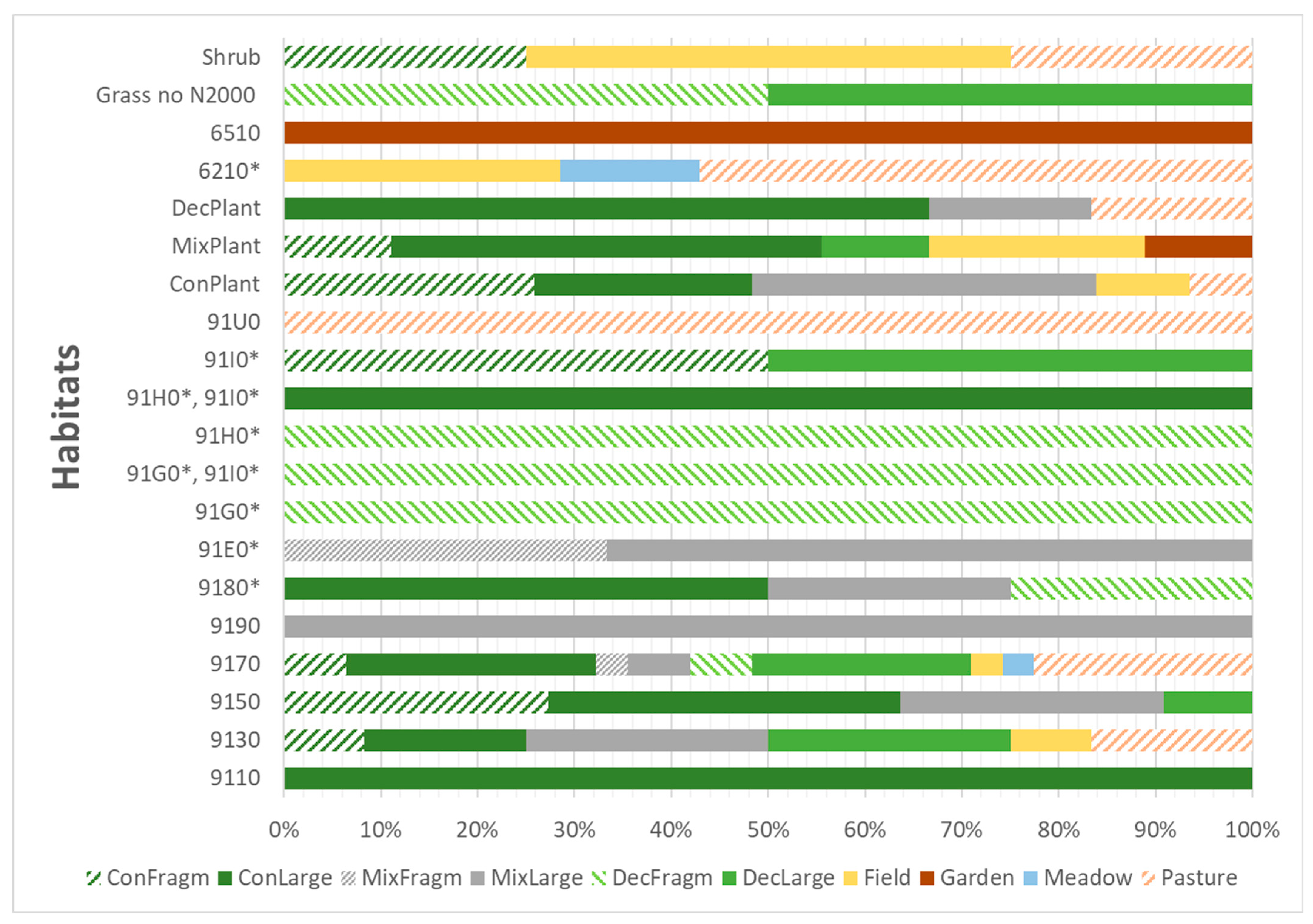

3.1. Current Occurrence

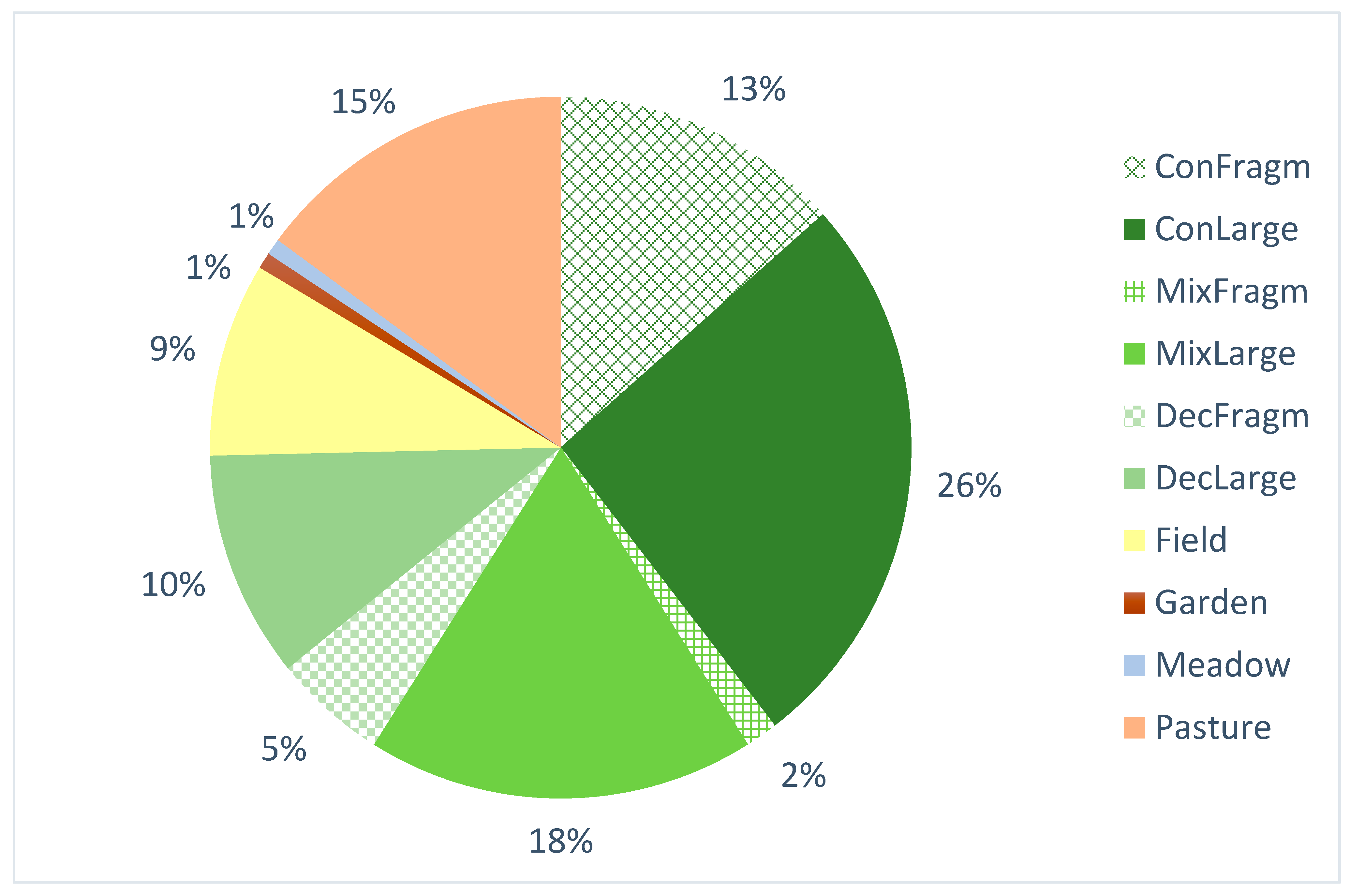

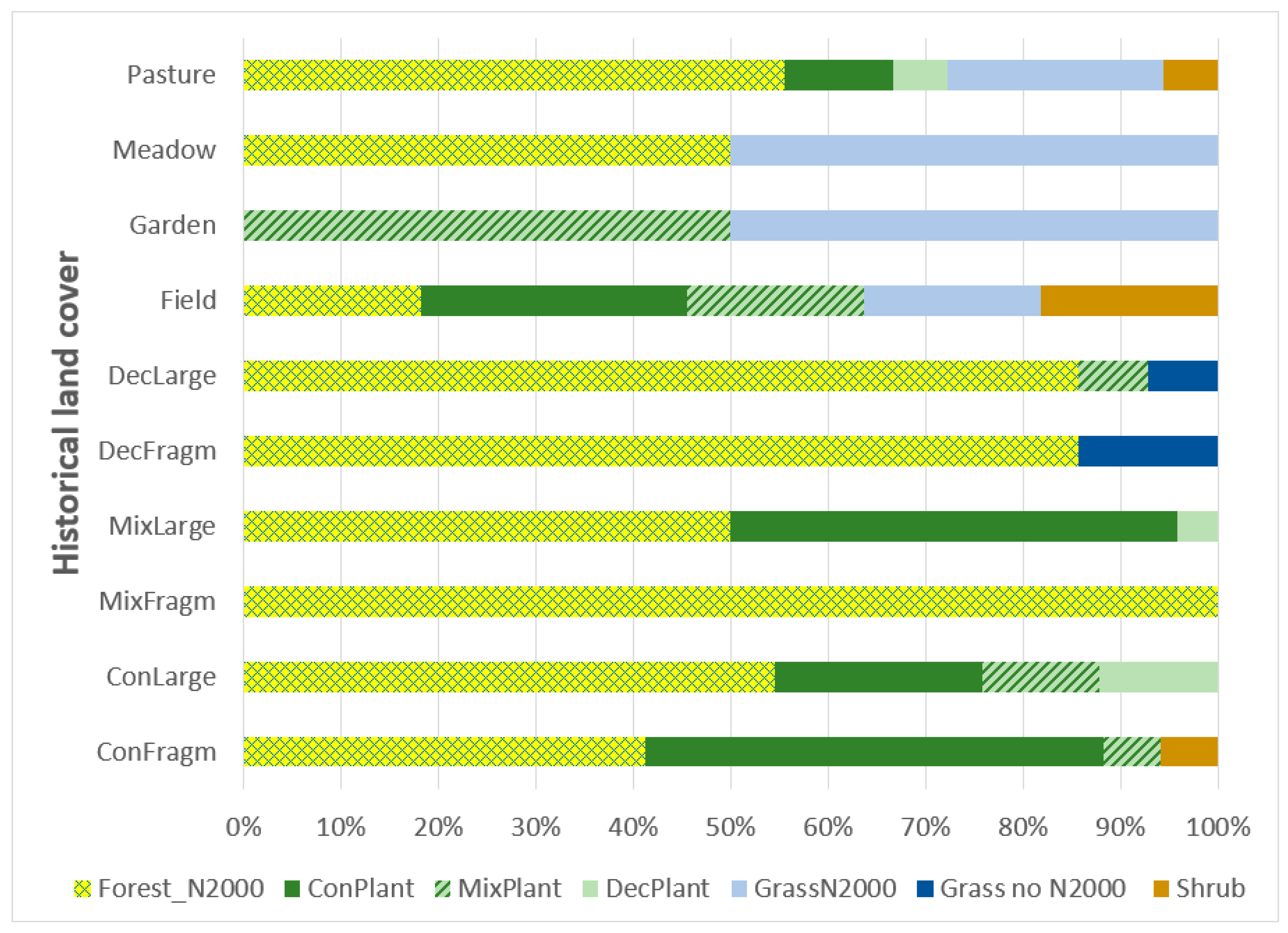

3.2. Historical Occurrence

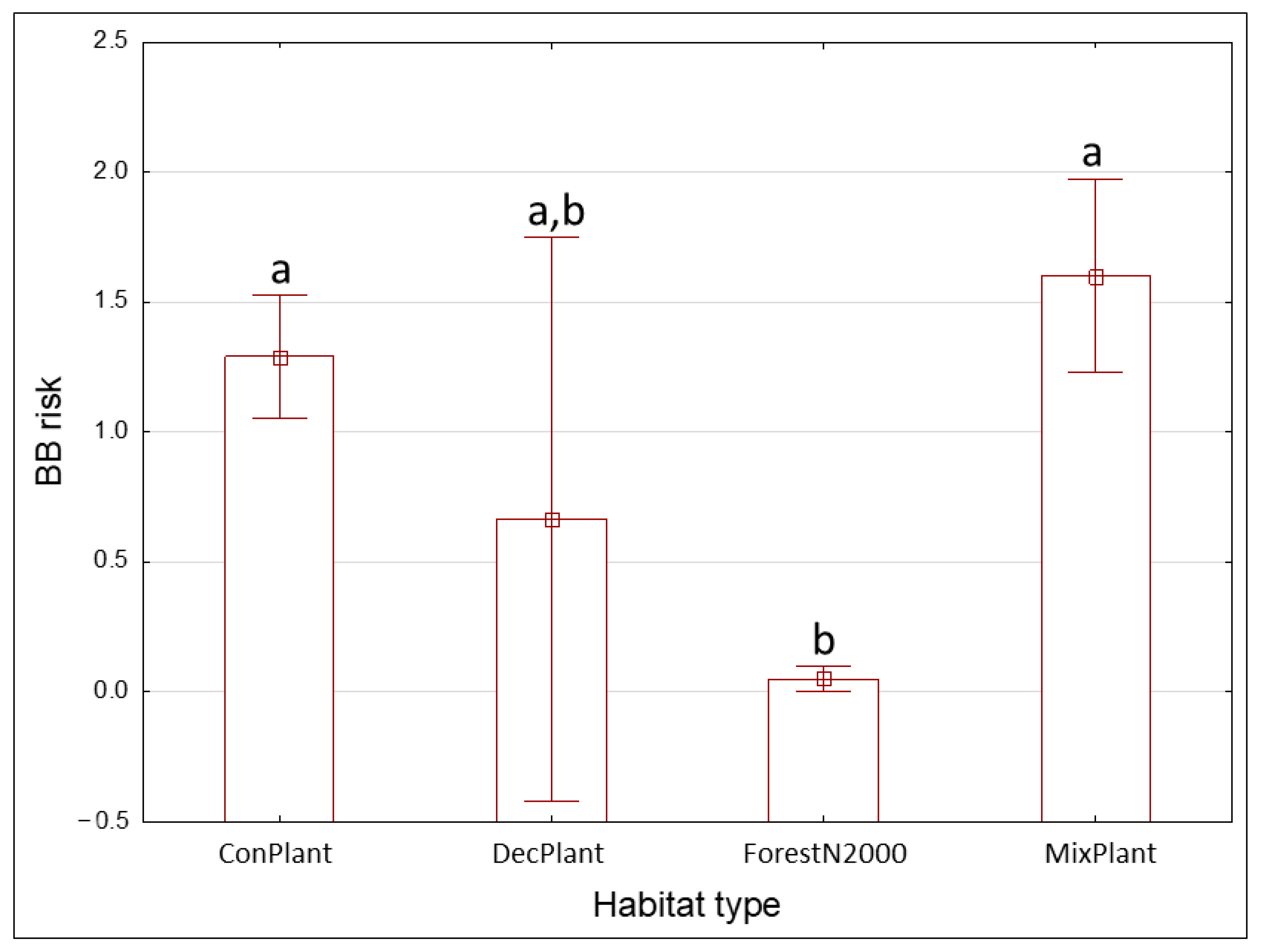

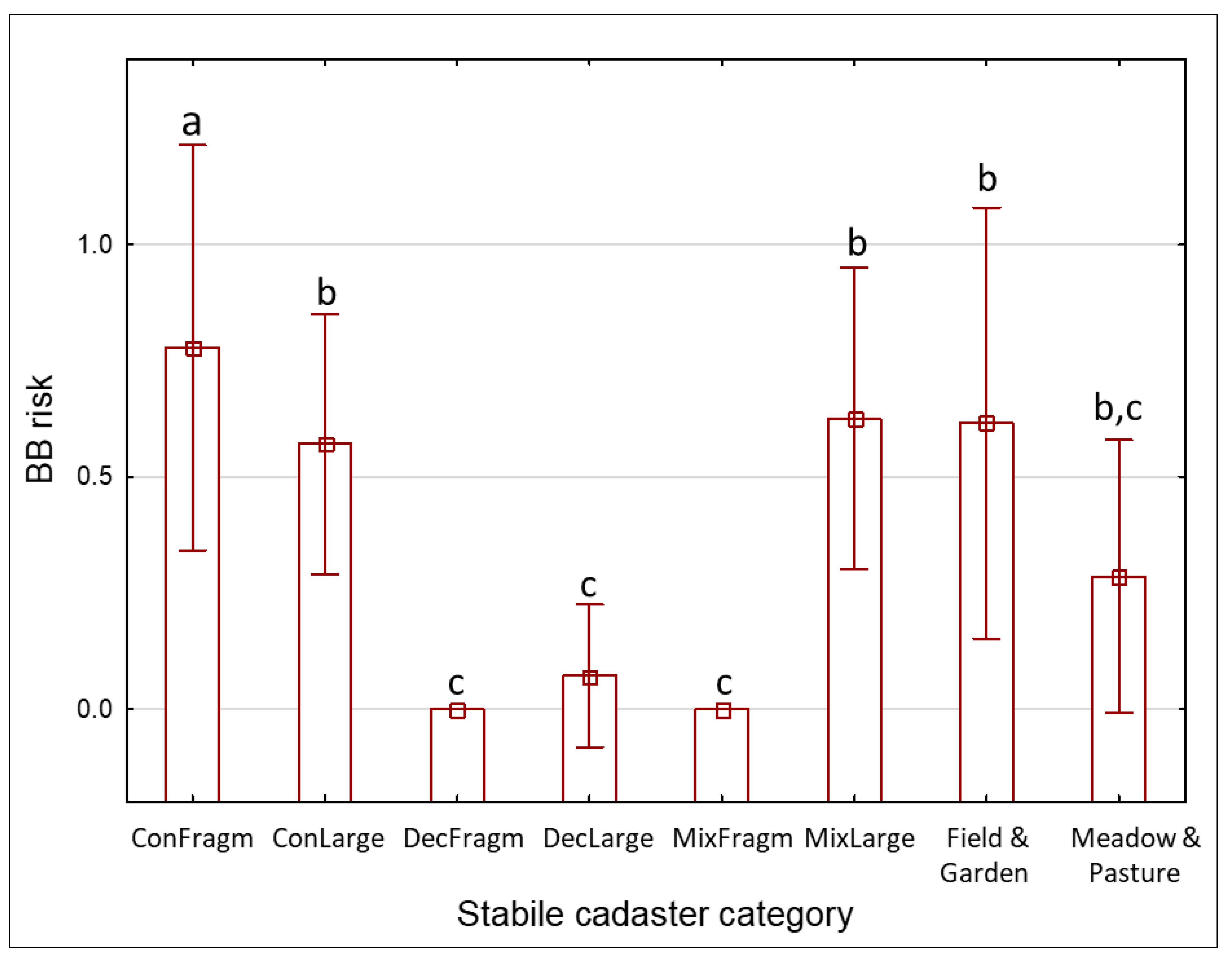

3.3. Risks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terschuren, J. Action Plan for Cypripedium calceolus in Europe—Report to the Council of Europe; Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats; T-PVS(98)20; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bilz, M. Cypripedium calceolus, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/162021/5532694 (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Jakubska-Busse, A.; Tsiftsis, S.; Śliwiński, M.; Křenová, Z.; Djordjević, V.; Steiu, C.; Kolanowska, M.; Efimov, P.; Hennigs, S.; Lustyk, P.; et al. How to protect natural habitats of rare terrestrial orchids effectively: A comparative case study of Cypripedium calceolus in different geographical regions of Europe. Plants 2021, 10, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, P.; Syrylak Sandison, M. A preliminary assessment of the conservation status of Cypripedium species in the wild. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1998, 126, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, E.; Fries, M. Atlas of North European Vascular Plants; Koeltz ScientiÆc Books: Köningstein, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Delforge, P. Orchids of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kull, T. Cypripedium calceolus L. J. Ecol. 1999, 87, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, T. Genet and ramet dynamics of Cypripedium calceolus in different habitats. Abstr. Bot. 1995, 19, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, H.N. Terrestrial Orchids: From Seed to Mycotrophic Plant; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, L.A. Anthecological studies on the Lady’s Slipper, Cypripedium calceolus (Orchidaceae). Bot. Not. 1979, 132, 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kull, T. Identification of clones in Cypripedium calceolus (Orchidaceae). Proc. Est. Acad. Sci. 1988, 37, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, M.F.; Taylor, I. 801. Cypripedium calceolus: Orchidaceae. Curtis’s Bot. Mag. 2015, 32, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytrý, M.; Danihelka, J.; Kaplan, Z.; Wild, J.; Holubová, D.; Novotný, P.; Řezníčková, M.; Rohn, M.; Dřevojan, P.; Grulich, V.; et al. Pladias Database of the Czech Flora and Vegetation. Preslia 2021, 93, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, F.; Velísek, V. Orchideje Naší Přírody [Orchids of our Nature]; Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turoňová, D.; Gillová, L. Střevíčník pantoflíček (Cypripedium calceolus)—Metodika Monitoringu [Monitoring Methods]. Master’s Thesis, Agentura ochrany přírody a krajiny ČR: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AOPK ČR. Nálezová Databáze Ochrany Přírody [Species Occurrence Database], On-Line Database; Agency of Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2022; Available online: https://portal.nature.cz/nd/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Gola, P. Ecobiological Exigenciens of Wood Populations Cypripedium calceolus L. Master’s Thesis, Department of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, University Palacky Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Härtel, H.; Lončáková, J.; Hošek, M. (Eds.) Mapování Biotopů v České Republice. Východiska, Výsledky, Perspektivy [Biotope Mapping in the Czech Republic. Background, Results, Perspectives]; Agency for Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chytrý, M.; Kučera, T.; Kočí, M.; Grulich, V.; Lustyk, P. (Eds.) Katalog Biotopů České Republiky [Catalog of Biotopes of the Czech Republic], 2nd ed.; Agency for Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FiNDB. Nálezová Databáze Biotopů [Habitat Occurrence Database], On-Line Database; Agency of Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2022; Available online: https://portal.nature.cz/mb/mb_nalez.php?X=X (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Semotánová, E. Historická Geografie Českých Zemí [Historical Geography of the Czech Lands]; Institute of History of the Czech Academy of Sciences: Prague, Czech Republic, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- STATISTICA v. 12; StatSoft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.statsoft.com (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Jakubska-Busse, A.; Szczęśniak, E.; Śliwiński, M.; Narkiewicz, C. Zanikanie stanowisk obuwika pospolitego Cypripedium calceolus L., 1753 (Orchidaceae) w Sudetach. Przyr. Sudet. 2010, 13, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, A. Studiul Popula¸tiei de Cypripedium calceolus L. din Împrejurimile Ora¸sului Sovata, Jude¸t Mures, Lucrare de Licen¸ta [Population Study of Cypripedium calceolus L. from the Surroundings of Sovata City; Mures County]; Universitatea “Babe¸s-Bolyai”: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2006; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Balázs, Z.R.; Roman, A.; Balazs, H.E.; Căpraş, D.; Podar, D. Rediscovery of Cypripedium calceolus L. in the vicinity of Cluj-Napoca (Romania) after 80 years. Contrib. Bot. 2016, 51, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tomescu, C.V. Cypripedium calceolus L. în pădurea Dragomirna–judeţul Suceava, in: Horticultură, Viticultură şi vinificaţie, Silvicultură şi grădini publice. Protecţia Plantelor 2018, 47, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, H. Die statistische Gefährdung des Frauenschuhs im mittleren Deutschland. Ber. Arbeitskrs. Heim. Orchid. 1996, 13, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karlik, P.; Poschlod, P. History or abiotic filter: Which is more important in determining the species composition of calcareous grasslands? Preslia 2009, 81, 321–340. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.B.; Peet, R.K.; Dengler, J.; Partel, M. Plant species richness: The world records. J. Veg. Sci. 2009, 23, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmeda, C.; Šefferová, V.; Underwood, E.; Millan, L.; Gil, T.; Naumann, S. (Eds.) EU Action Plan to Maintain and Restore to Favourable Conservation Status the Habitat Type 6210 Semi-Natural Dry Grasslands and Scrubland Facies on Calcareous Substrates (Festuco-Brometalia) (*Important Orchid Sites); European Commission Technical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://ieep.eu/publications/eu-habitat-action-plans-targeting-restoration-of-key-habitats-and-species (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Chytrý, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Novák, J. Suché trávníky [Dry grasslands]. In Vegetace České Republiky 1. Travinná a keříčková vegetace [Vegetation of the Czech Republic 1. Grassland and Heathland Vegetation]; Chytrý, M., Ed.; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007; pp. 371–470. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharczyk, M. Cypripedium calceolus L., Obuwik pospolity. In Gatunki roślin. Poradniki Ochrony Siedlisk i Gatunków Natura 2000—Podręcznik Metodyczny. Tom 9; Sudnik-Wojciechowska, B., Werblan-Jakubiec, H., Eds.; Ministerstwo Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2004; pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczakowa, R. Polish Red List of Pteridophytes and Flowering Plants; Institute of Nature Conservation Polish Academy of Sciences: Krakow, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niklfeld, H.; Schratt-Ehrendorfer, L. Rote Liste gefährdeter Farn- und Blütenpflanzen (Pteridophyta und Spermatophyta) Österreichs. 2. Fassung. In Rote Listen Gefährdeter Pflanzen Österreichs; 2. Auflage; Grüne Reihe des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Jugend und Familie, Band 10; Niklfeld, H., Ed.; Austria Medien Service: Graz, Austria, 1999; pp. 33–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gudžinskas, Z.; Ryla, M. Lietuvos Gegužraibiniai (Orchidaceae), Botanikos Instituto Leidykla; Spausdino UAB, Petro Ofsetas: Žalgirio, Lithuania, 2006; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Ingelög, T.; Andersson, R.; Tjernberg, M. Red Data Book of the Baltic Region. Part 1: Lists of Threatened Vascular Plants and Vertebrates; Swedish Threatened Species Unit Uppsala: Riga, Latvia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Klavina, D.; Grauda, D.; Priede, A.; Rashal, I. The habitat diversity and genetic variability of Cypripedium calceolus in Latvia. In Actions for Wild Plants, Proceedings of the 6th Planta Europa Conference on the Conservation of Plants, Kraków, Poland, 23–27 May 2011; Committee on Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences: Kraków, Poland, 2011; pp. 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, M.J.; Luyssaert, S.; Meyfroidt, P.; Kaplan, J.O.; Bürgi, M.; Chen, Y. Reconstructing European forest management from 1600 to 2010. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2015, 12, 5365–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakuš, R.; Blaženec, M. (Eds.) Principy Ochrany Dospelých Smrekových Porastov pred Podkornym Hmyzom [Principles of Protection of Adult Spruce Stands against Bark Beetles]; Institute of Forest Ecology, the Slovak Academy of Sciences: Zvolen, Slovensko, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Land Cover Category | Historical Land Cover of the Site Where the C. calceolus Population Recently Occurs |

|---|---|---|

| ConFragm | Coniferous forest

| The site was historically located in a coniferous forest of size < 1 km2 OR in a mosaic of coniferous forests and grasslands. |

| ConLarge | Coniferous forest

| The site was historically located in a coniferous forest of size > 1 km2. |

| MixFragm | Mixed forest

| The site was historically located in a mixed forest of size < 1 km2 OR in a mosaic of mixed forests and grasslands. |

| MixLarge | Mixed forest

| The site was historically located in a mixed forest of size > 1 km2. |

| DecFragm | Deciduous forest

| The site was historically located in a deciduous forest of size < 1 km2 OR in a mosaic of deciduous forests and grasslands. |

| DecLarge | Deciduous forest

| The site was historically located in a deciduous forest of size > 1 km2. |

| Field | Fields

| The site was historically located in properties mapped as a field or arable land. The intensity and types of applied management measures could have changed over time. |

| Garden | Garden | The site was historically mapped as a garden. The intensity and types of applied management measures could have changed over time. |

| Meadow | Meadow | The site was historically mapped as a meadow. It was probably a permanent (semi-natural) grassland habitat. |

| Pasture | Pasture | The site was historically mapped as a pasture. It was probably a permanent (semi-natural) grassland habitat. |

| Code | Risk Category | Description of Forest in the Vicinity of C. calceolus Population |

|---|---|---|

| Risk 0 | a zero-risk forest | without spruce trees OR spruce trees cover <10% of the buffer zone and no occurrence of bark beetle trees was recorded during the last five years |

| Risk 1 | a low-risk forest | mixed forests with less than 50% of spruce trees |

| Risk 2 | a high-risk forest | spruce monoculture OR mixed forests with less than 50% of spruce trees and occurrence of bark beetle trees during the last five years OR mixed forests with more than 50% of spruce trees and no occurrence of bark beetle trees recorded during the last five years |

| Natura 2000 | Habitat Code | Habitat Name | Number of Populations | Population Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | ||||

| yes | 9110 | Luzulo-Fagetum beech forests | 1 | 1.00 | 1 | 1 |

| yes | 9130 | Asperulo-Fagetum beech forests | 12 | 35.09 | 1 | 169 |

| yes | 9150 | Medio-European limestone beech forests of the Cephalanthero-Fagion | 11 | 11.40 | 2 | 64 |

| yes | 9170 | Galio-Carpinetum oak-hornbeam forests | 31 | 21.48 | 1 | 120 |

| yes | 9190 | Old acidophilous oak woods with Quercus robur on sandy plains | 1 | 1.00 | 1 | 1 |

| yes | 9180 * | Tilio-Acerion forests of slopes, screes, and ravines. | 4 | 28.00 | 1 | 95 |

| yes | 91E0 * | Alluvial forests of Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior (Alno-Padion, Alnion incanae, Salicion albae) | 3 | 3.67 | 3 | 4 |

| yes | 91G0 * | Pannonic woods with Quercus petraea and Carpinus betulus | 1 | 4.00 | 4 | 4 |

| yes | 91G0 *, 91I0 * | mosaic of 91G0 * & 91I0 * | 1 | 8.00 | 8 | 8 |

| yes | 91H0 * | Pannonian woods with Quercus pubescens. | 1 | 32.00 | 32 | 32 |

| yes | 91H0 *, 91I0 * | mosaic of 91H0 * & 91I0 * | 1 | 62.00 | 62 | 62 |

| yes | 91I0 * | Euro-Siberian steppe oak woods | 2 | 3.50 | 2 | 5 |

| yes | 91U0 | Sarmatic steppe pine forests | 1 | 25.00 | 25 | 25 |

| no | ConPlant | Coniferous plantations, often spruce monocultures | 33 | 8.41 | 1 | 76 |

| no | DecPlant | Deciduous plantations | 6 | 44.33 | 1 | 135 |

| no | MixPlant | Mixed tree plantations or mixture of succession and planted trees | 11 | 61.64 | 1 | 462 |

| yes | 6210 * | Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates (Festuco-Brometalia) | 8 | 6.63 | 1 | 25 |

| yes | 6510 | Lowland hay meadows (Alopecurus pratensis, Sanguisorba officinalis) | 1 | 46.00 | 46 | 46 |

| no | Grass no N2000 | Grasslands, no Natura 2000 habitats | 2 | 18.50 | 4 | 33 |

| no | Shrubs | Scrublands, no Natura 2000 habitats—usual succession of abandoned meadows or edges of forests | 5 | 12.60 | 1 | 47 |

| Code of Historical Land Cover Category | Number of Populations | Population Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Min | Max | ||

| ConFragm | 18 | 17.60 | 1 | 124 |

| ConLarge | 35 | 21.51 | 1 | 120 |

| MixFragm | 2 | 25.50 | 4 | 47 |

| MixLarge | 24 | 12.46 | 1 | 102 |

| DecFragm | 7 | 15.29 | 2 | 33 |

| DecLarge | 15 | 17.50 | 1 | 160 |

| Field | 12 | 58.83 | 1 | 462 |

| Garden | 1 | 46.00 | 46 | 46 |

| Meadow | 2 | 1.50 | 1 | 2 |

| Pasture | 20 | 18.67 | 1 | 75 |

| Management Type | Bark Beetle Measures | Effect on C. calceolus Populations |

|---|---|---|

| Type A | Salvage logging: bark beetle-infected trees are logged, wood removed, litter burned, the site is cleaned, and new trees are planted. | Individual plants are destroyed, and the quality of the biotope fundamentally deteriorates. The movement of heavy forestry equipment, handling of the soil, and the modification of the site during the planting of new trees cause damage to the underground parts of orchids and seed banks. Natural recovery of the orchid population is not possible. |

| Type B | Salvage logging: bark beetle-infected trees are logged; debarked trunks are left on the ground to decompose, and new trees are planted. | |

| Type C | Salvage logging: bark beetle-infected trees are logged, debarked trunks are left on the ground to decompose, and natural regeneration is allowed. | Individual orchids are destroyed, and the quality of the biotope significantly deteriorates. Driving heavy forestry equipment and handling debarked trunks will significantly damage the underground parts of orchids and seed banks. Natural recovery of the orchid population is probably impossible. |

| Type D | Debarking of standing trees or bark-scratching of storm felled trees; bark beetle-infected trees are debarked or bark-scratched, the site is cleaned, and new trees are planted. | Some orchids are destroyed, and the quality of the biotope partially deteriorated. In the case of planting new trees, the underground parts of the orchids and the seed bank may be damaged. The natural recovery of the orchid population is significantly weakened. |

| Type E | Debarking of standing trees or bark-scratching of storm-felled trees; bark beetle-infected trees are debarked, or bark-scratched, and natural regeneration is allowed. | Some orchids are destroyed, and the quality of the biotope partially deteriorated. The natural recovery of the orchid population is limited. |

| Type F | Mixed management: salvage logging is applied only partly and at least 50% of standing trees must be left in a site (green, debarked, or bark-scratched) to maintain partial shade for C. calceolus. No planting of new trees or natural regeneration is allowed. | In zones where active bark beetle management is applied, damage to orchids, including their underground parts, may occur. However, the C. calceolous population at least partially benefits from the removal of bark trees or their killing by the bark beetle. |

| Type G | No intervention: bark beetle-infected trees are not managed, and natural regeneration is allowed. All management measures are located in a buffer zone located at a distance of at least 30 m from C. calceolus specimens. | Orchids are not destroyed, and the habitat of the condition is improved. The C. calceolous population benefits from the removal of bark trees in the buffer zone. Dry bark trees in the C. calceolous site can provide desirable partial shade. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Křenová, Z.; Lustyk, P.; Kindlmann, P.; Vosmíková, A. Forest Disturbances Threatening Cypripedium calceolus Populations Can Improve Its Habitat Conditions. Diversity 2023, 15, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15030319

Křenová Z, Lustyk P, Kindlmann P, Vosmíková A. Forest Disturbances Threatening Cypripedium calceolus Populations Can Improve Its Habitat Conditions. Diversity. 2023; 15(3):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15030319

Chicago/Turabian StyleKřenová, Zdenka, Pavel Lustyk, Pavel Kindlmann, and Alžběta Vosmíková. 2023. "Forest Disturbances Threatening Cypripedium calceolus Populations Can Improve Its Habitat Conditions" Diversity 15, no. 3: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15030319

APA StyleKřenová, Z., Lustyk, P., Kindlmann, P., & Vosmíková, A. (2023). Forest Disturbances Threatening Cypripedium calceolus Populations Can Improve Its Habitat Conditions. Diversity, 15(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15030319