Actual State of Knowledge of the Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrade Fauna of the Republic of Argentina and New Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944)

Abstract

1. Introduction

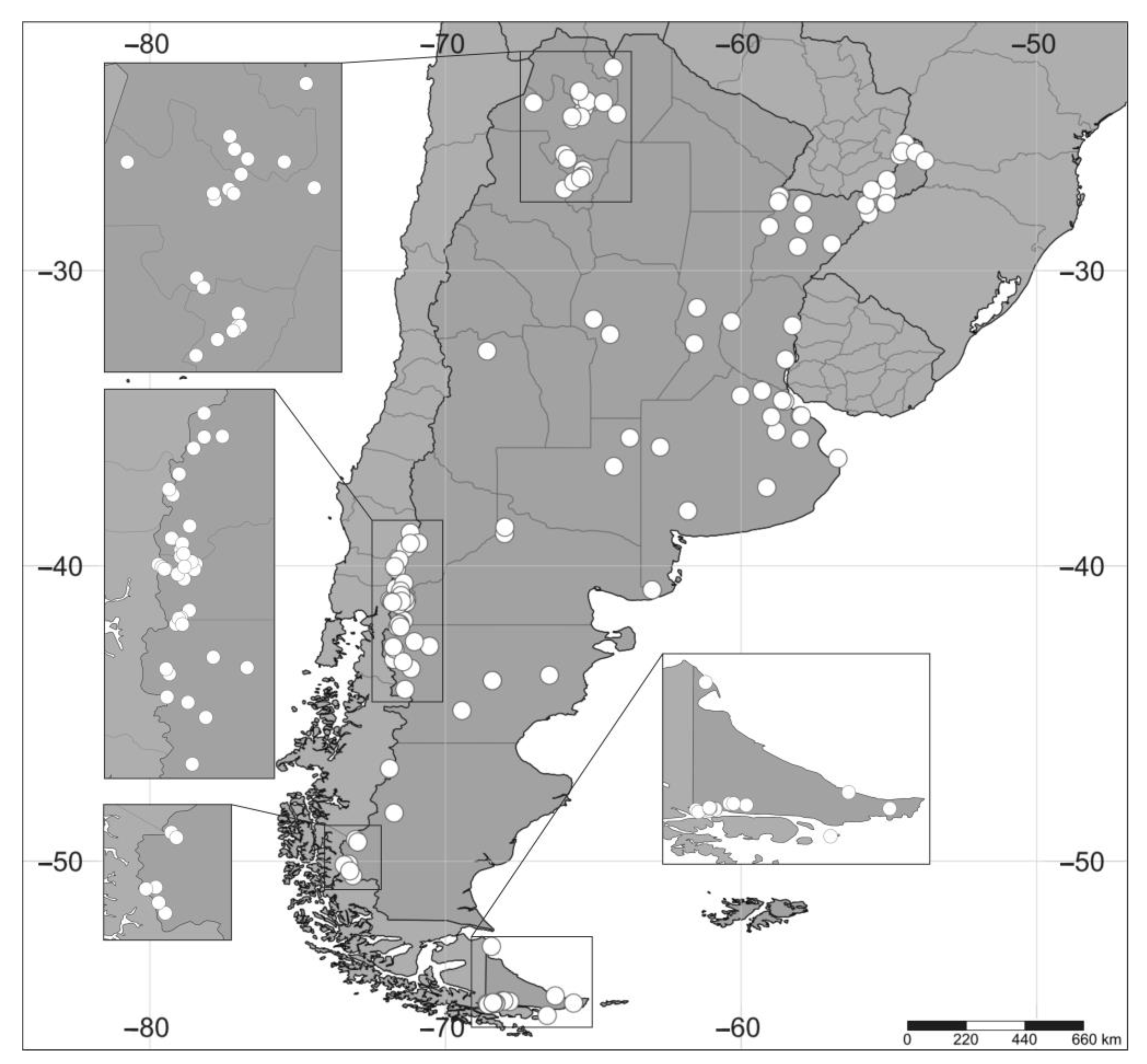

2. Materials and Methods

| Order, Family | Species/Subspecies | Status (Record Reliability) | Province | Report for Argentina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Antechiniscus jermani Rossi & Claps, 1989 | + | RN | [33] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Antechiniscus lateromamillatus (Ramazzotti, 1964) | + | NQN | [36] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria bigranulata (Richters, 1907) | + | BA; ER; CR; MI; TU; SA; NQN; RN; CT; SC; TF(SS) | [8,9,13,15,29,30,31,32,33,36] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria charrua (Claps & Rossi, 1997) | + | MI; TU | [8] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria jenningsi (Dastych, 1984) | + | TF(IAS) | [35] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria madonnae (Michalczyk & Kaczmarek, 2006) | + | CT | [8] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria ollantaytamboensis (Nickel, Miller & Marley, 2001) | + | SA | [8] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria paucigranulata Wilamowski, Vončina, Gąsiorek & Michalczyk, 2022 | + | SA | [8] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria cf. rufoviridis comb. nov. (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944) | + * | BA; LP; SF | [37,38,47] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria weglarskae Gąsiorek, Wilamowski, Vončina & Michalczyk, 2022 | + | SC | [8] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Bryodelphax parvulus Thulin, 1928 | + * | RN | [16,17] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Claxtonia capillata (Ramazzotti, 1956) | + * | TU; RN; CT | [29,30,33] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Claxtonia corrugicaudata (McInnes, 2010) | + | RN | [27] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Claxtonia marginopora (Grigarick, Schuster & Nelson, 1983) | + | SC | [13] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Claxtonia wendti (Dastych, 1984) | N | RN; CT; SC; TF(SS) | [10,13,29] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Cornechiniscus lobatus (Ramazzotti, 1943) | + | SA | [50] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus aonikenk Gasiorek, Bochnak, Vončina & Michalczyk, 2021 | + | CT | [51] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus arctomys Ehrenberg, 1853 | N | RN | [9] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus blumi Richters, 1903 | + * | RN; CT; SC | [9,13,16,17,29,33] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus canadensis Murray, 1910 | + * | RN | [16] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus columinis Murray, 1911 | + | SC | [33] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus crassispinosus Murray, 1907 | + * | MI | [31] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus dreyfusi de Barros, 1942 | + | MI | [31] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus evelinae de Barros, 1942 | + | TU | [51] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus manuelae da Cunha & do Nascimento Ribeiro, 1962 | + | CR; MI; SA | [31,51] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus merokensis merokensis Richters, 1904 | + * | NQN; RN; SC; TF(SS) | [6,13,36] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus pellucidus Gasiorek, Bochnak, Vončina & Michalczyk, 2021 | + | CT | [51] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus testudo (Doyère, 1840) | + | RN; CT; SC | [33,51] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus trisetosus Cuénot, 1932 | + * | CT | [29] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Mopsechiniscus granulosus Mihelčič, 1967 | + | NQN; RN; CT | [5,7,16,17,29,33,36] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Mopsechiniscus imberbis (Richters, 1907) | N | TF(IAS) | [35] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Pseudechiniscus (Meridioniscus) bartkei Węglarska, 1962 | + * | SA; RN TF(SS) | [30,33] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Pseudechiniscus (Meridioniscus) saltensis Rocha, Doma, González-Reyes & Lisi, 2020 | + | SA | [42] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Pseudechiniscus (Pseudechiniscus) marinae Bartoš, 1934 | + * | RN | [9] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Pseudechiniscus (Pseudechiniscus) suillus (Ehrenberg, 1853) | + * | MI; RN; SC | [13,16,17,31] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Testechiniscus spitsbergensis spitsbergensis (Scourfield, 1897) | + * | CT; SC | [29,33] |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Viridiscus viridis (Murray, 1910) | N | NQN | [29] |

| Echiniscoidea, Oreellidae | Oreella mollis (Murray, 1910) | + | CT | [5] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium argentinum Roszkowska, Ostrowska & Kaczmarek, 2015 | + | RN | [26,27] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium beatae Roszkowska, Ostrowska & Kaczmarek, 2015 | + | RN | [26,27] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium brachyungue Binda & Pilato, 1990 | + | RN | [26,27] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium eurystomum Maucci, 1991 | + * | SC | [14] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium granulatum Ramazzotti, 1962 | + | RN | [26,27] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium irenae Rocha, González-Reyes, Ostertag & Lisi, 2022 | + | LP | [43,52] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium kogui Londoño, Daza, Caicedo, Quiroga & Kaczmarek, 2015 | + | SA | [41] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium pelufforum Rocha, González-Reyes, Ostertag & Lisi, 2022 | + | SA | [43,52] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium quiranae Rocha, González-Reyes, Ostertag & Lisi, 2022 | + | SA | [43,52] |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium tardigradum Doyère, 1840 | N | BA; ER; CR; CH; TU; SA; JY; LP; NQN; RN; CT; SC; TF(SS); TF(IAS) | [9,16,29,30,31,32,33,36] |

| Parachela, Calohypsibiidae | Calohypsibius ornatus (Richters, 1900) | + * | RN | [16,17] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Doryphoribius cephalogibbosus Rocha, Doma, González-Reyes & Lisi, 2020 | + | SA | [42] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Doryphoribius evelinae (Marcus, 1928) | + * | CR | [31] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Doryphoribius zappalai Pilato, 1971 | + * | SA; SC | [30,33,34] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Grevenius asper (Murray, 1906) | + * | MI; TU; JY | [30,31,34] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Grevenius deflexus (Mihelčič, 1960) | + | BA | [34] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Pseudobiotus megalonyx (Thulin, 1928) | + * | BA; CR; CB | [35] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Thulinius augusti (Murray, 1907) | + | BA; CR; CB | [30,31,34] |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Thulinius stephaniae (Pilato, 1974) | + * | BA | [34] |

| Parachela, Hexapodibiidae | Parhexapodibius castrii (Ramazzotti, 1964) | + | RN | [34] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Notahypsibius arcticus (Murray, 1907) | + | TF(IAS) | [35] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Acutuncus antarcticus (Richters, 1904) | + * | NQN | [35,36] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Adropion greveni (Dastych, 1984) | + | TF(SS) | [6] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Adropion scoticum (Murray, 1905) | + * | RN; CT; SC; TF(SS) | [9,13,16,17,25,33] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon alpinum Murray, 1906 | N | RN | [29,33] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon chilenense Plate, 1888 | + | RN | [17,29,33] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon mitrense Pilato, Binda & Qualtieri, 1999 | + | RN | [22] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon ongulense Morikawa, 1962 | + | TF(SS) | [33] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon pingue pingue (Marcus 1936) | N | TU; JY; RN | [9,30,33] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon stappersi Richters, 1911 | N | RN | [9] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon tenue Thulin, 1928 | N | NQN; RN | [33,36] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius allisoni Horning, Schuster & Grigarick, 1978 | + | SC; TF(SS) | [6,13] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius convergens (Urbanowicz, 1925) | + | TU; NQN; RN; SC | [10,13,17,29,30,33,36] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius dujardini (Doyère, 1840) | + * | TU; NQN; RN; CT; SC; TF(SS) | [9,30,33] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius marcelli Pilato, 1990 | + | BA; TF(SS) | [19] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius microps Thulin, 1928 | N | BA; ER; NQN; RN; SC | [9,13,32,33,36] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius montanus Iharos, 1940 | + * | CT | [29] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius pallidus Thulin, 1911 | N | NQN | [36] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Itaquascon umbellinae de Barros, 1939 | + | SC | [13] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Mixibius fueginus Pilato & Binda, 1996 | + | TF(SS) | [6,20] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Mixibius saracenus (Pilato, 1973) | + | TF(SS) | [6] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Pilatobius brevipes (Marcus, 1936) | + * | RN; TF(SS) | [10,29] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Pilatobius bullatus (Murray, 1905) | + * | RN; CT | [9,17] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Pilatobius recamieri (Richters, 1911) | + * | RN | [9,29,34] |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Platicrista angustata (Murray, 1905) | + * | RN; SC | [13,34] |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Dianea papillifera (Murray, 1905) | + | TF(IAS) | [35] |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Dianea sattleri (Richters, 1902) | + * | RN | [9,17] |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Isohypsibius prosostomus Thulin 1928 | + * | CB | [17] |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Isohypsibius sculptus (Ramazzotti, 1962) | + | NQN; RN | [9] |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Ursulinius nodosus (Murray, 1907) | N | RN; CT | [9] |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Ursulinius tucumanensis (Claps & Rossi, 1984) | + | TU | [30,35] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus anderssoni Richters, 1908 | + | RN; TF(SS) | [25] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus andinus Maucci, 1988 | + | RN; SC | [13] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus echinogenitus Richters, 1903 | + * | SA; CT; TF(SS) | [17,18,23,24,29,30] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus hufelandi C.A.S. Schultze, 1833 | N | BA; ER; CR; MI; CB; TU; SA; JY; NQN; RN; CT; SC; TF(SS) | [9,13,16,17,25,29,30,31,32,33] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus kazmierskii Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2009 | + | RN | [12] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus kristenseni Guidetti, Peluffo, Rocha, Cesari & Moly de Peluffo, 2013 | + | LP | [40] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus occidentalis Murray, 1910 | + * | RN | [9] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus papillosus Iharos, 1963 | + | RN | [9] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus patagonicus Maucci, 1988 | + | NQN; RN; SC | [13,36] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus porteri Rahm, 1931 | + | ? | [17] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus coronatus de Barros, 1942 | + | BA | [32] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus erminiae Binda & Pilato, 1999 | + * | TF(SS) | [6] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus furciger (Murray, 1906) | + * | RN; CT; TF(SS) | [17,25,29] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus harmsworthi (Murray, 1907) | N | CR; RN; SC | [9,13,17,31] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus montanus Murray, 1910 | + * | RN | [10] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus neuquensis Rossi, Claps & Ardohain, 2009 | + | NQN | [36] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus nuragicus (Pilato & Sperlinga, 1975) | + * | RN | [34] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus orcadensis (Murray, 1907) | + | CR; TF(SS) | [31,33] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus ovostriatus (Pilato & Patanè, 1998) | + | TF(SS) | [21] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus pseudoblocki Roszkowska, Stec, Ciobanu & Kaczmarek, 2016 | + | RN | [27] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus szeptyckii (Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2009) | + | RN | [12] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus tehuelchensis (Rossi, Claps & Ardohain, 2009) | + | NQN | [36] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus acontistus (de Barros, 1942) | + | CR; MI | [17,31] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus claxtonae Rossi, Claps & Ardohain, 2009 | + | NQN | [36] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus furcatus (Ehrenberg, 1859) | + | BA; TF(SS) | [35] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus intermedius (Plate, 1888) | + * | ER; CR; RN; TF(SS) | [9,10,16,17,31] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus pseudostellarus Roszkowska, Stec, Ciobanu & Kaczmarek, 2016 | + | RN | [27] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus subintermedius (Ramazzotti, 1962) | + | NQN; CB | [29,36] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Paramacrobiotus areolatus (Murray, 1907) | + * | BA; CR; SA; LP; RN; SC | [13,30,31,32,33,38,39] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Paramacrobiotus richtersi (Murray, 1911) | + * | BA; CR; MI; TU; SA; JY; NQN; RN; CT; TF(SS) | [9,10,29,30,31,32,33] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Schusterius tridigitus (Schuster, 1983) | + | TF(SS) | [11,28] |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Sisubiotus spectabilis (Thulin, 1928) | + * | SA | [30] |

| Parachela, Murrayidae | Dactylobiotus ambiguus (Murray, 1907) | + * | BA; RN; TF(IAS) | [34] |

| Parachela, Murrayidae | Dactylobiotus dispar (Murray, 1907) | + * | BA; CR; JY; RN | [30,33,34] |

| Parachela, Murrayidae | Dactylobiotus grandipes (Schuster, Toftner & Grigarick, 1978) | + | LP | [35] |

| Parachela, Murrayidae | Dactylobiotus lombardoi Binda & Pilato, 1999 | + | TF(IAS) | [35] |

| Parachela, Murrayidae | Dactylobiotus parthenogeneticus Bertolani, 1981 | + * | BA; SJ; NQN | [34] |

| Parachela, Murrayidae | Murrayon pullari (Murray, 1907) | + * | TF(SS) | [33] |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Hebesuncus conjungens (Thulin, 1911) | + * | NQN; RN; SC | [13,16,17,29,33] |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Hebesuncus mollispinus Pilato, McInnes & Lisi, 2012 | + | RN | [27] |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Ramazzottius anomalus (Ramazzotti, 1962) | + * | ER; SA; SJ | [30,31] |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Ramazzottius baumanni (Ramazzotti, 1962) | + * | ER; SA; JY; NQN; RN; CT; SC | [9,13,29,30,31,33,36] |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri (Doyère, 1840) | + * | MI; SA; LP; RN; CT; TF(SS) | [16,17,25,30,31,33,38] |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Ramazzottius saltensis Claps & Rossi, 1984 | + | SA | [30] |

3. Results

3.1. Actual Checklist of Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrades of Argentina

- (1)

- For Minibiotus intermedius (Plate, 1888) (indeed, indicated as “+” in Kaczmarek et al. [46], but, to be cautious, we put it into the “+ *” category). The only other Minibiotus R.O. Schuster, 1980, species of the list of the intermedius group with smooth cuticle is M. acontistus (de Barros, 1942), but the questioned records of M. intermedius were together with records of M. acontistus [17,31], indicating that the pertinent authors were able to distinguish between them.

- (2)

- For Ramazzottius oberhaeuserii (Doyère, 1840), two species of the genus reported for Argentina, R. anomalus (Ramazzotti, 1962) and R. baumanni (Ramazzotti, 1962), were described with notorious characters distinguishing them from R. oberhaeuseri. All three species were recorded together in Claps and Rossi [31]; similarly, the fourth Argentine species, R. saltensis, was recorded together with R. oberhaeuseri in Claps and Rossi [30]. All this clearly indicates no confusion between R. oberhaeuseri and the other three congeneric species.

- (3)

- The three dubious species of the genus Dactylobiotus R.O. Schuster, 1980, and the only two species of the genus Grevenius Gąsiorek, Stec, Morek & Michalczyk, 2019, were recorded together in Rossi and Claps [34], and the only two species of the genus Paramacrobiotus Guidetti, Schill, Bertolani, Dandekar & Wolf, 2009, were recorded together in Claps and Rossi [30,31] and Rossi and Claps [32,33].

3.2. Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944): Barbaria rufoviridis comb. nov.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Degma, P.; Guidetti, R. Actual Checklist of Tardigrada Species, 41st ed.; University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: Modena, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://iris.unimore.it/retrieve/e31e1250-6907-987f-e053-3705fe0a095a/Actual%20 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Nelson, D.R.; Bartels, P.J.; Guil, N. Tardigrade ecology. In Water Bears: The Biology of Tardigrades; Schill, R.O., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 163–210. [Google Scholar]

- Degma, P.; Bertolani, R.; Guidetti, R. Actual Checklist of Tardigrada Species, 22nd ed.; University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: Modena, Italy, 2013; p. 37. Available online: http://www.tardigrada.modena.unimo.it/miscellanea/Actual%20checklist%20of%20Tardigrada.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- De Wet, J.; Shoonbee, H. The occurrence and conservation status of Ceratogyrus bechuanicus and C. brachycephalus in the Transvaal, South Africa. Koedoe 1991, 34, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, M.; Kristensen, R. Notes on the genus Oreella (Oreellidae) and the systematic position of Carphania fluviatilis Binda, 1978 (Carphanidae fam. nov., Heterotardigrada). Animalia 1986, 13, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Binda, M.; Pilato, G. Macrobiotus erminiae, new species of eutardigrade from southern Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Entomol. Mitt. Zool. Mus. Hamb. 1999, 13, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dastych, H. Redescription of the Neotropical tardigrade Mopsechiniscus granulosus Mihelčič, 1967 (Tardigrada). Mitt. Hamb. Zool. Mus. Inst. 2000, 97, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gąsiorek, P.; Wilamowski, A.; Vončina, K.; Michalczyk, Ł. Neotropical jewels in the moss: Biodiversity, distribution and evolution of the genus Barbaria (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2022, 195, 1037–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iharos, G. The zoological results of Gy. Topal’s collections in South Argentina, 3. Tardigrada. Ann. Hist. Nat. Mus. Nat. Hung. 1963, 55, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Iharos, G. Tardigradologische Notizen, I. Miscnea Zool. Hung. 1982, 1, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł. Redescription of Macrobious tridigitus Schuster, 1983 and erection of a new genus of Tardigrada (Eutardigrada, Macrobiotidae). J. Nat. Hist. 2006, 40, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł. Two new species of Macrobiotidae, Macrobiotus szeptyckii (harmsworthi group) and Macrobiotus kazmierskii (hufelandi group) from Argentina. Acta Zool. Cracov. 2009, 52B, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maucci, W. Tardigrada from Patagonia, Southern South America, with description of three new species. Rev. Chil. Entomol. 1988, 16, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maucci, W. Tardigrada of the Arctic tundra with descriptions of two new species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 1996, 116, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, Ł.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Revision of the Echiniscus bigranulatus group with a description of a new species Echiniscus madonnae (Tardigrada: Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae) from South America. Zootaxa 2006, 1154, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelčič, F. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Tardigraden Argentiniens. Verh. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 1967, 107, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mihelčič, F. Ein weiterer Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Tardigraden Argentiniens. Verh. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 1972, 110/111, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. Tardigrada. British Antarctic Expedition 1907–1909. Reports Scient. Invest. 1910, 1, 83–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pilato, G. Tardigradi di Tierra del Fuoco e Magallanes. II. Descrizione di Hypsibius marcelli n. sp. (Hypsibiidae). Animalia 1990, 17, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pilato, G.; Binda, M. Mixibius fueginus, nuova specie di eutardigrado della Terra del Fuoco. Boll. Accad. Gioenia Sci. Nat. Catania 1996, 29, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pilato, G.; Patanè, M. Macrobiotus ovostriatus, a new species of eutardigrade from Tierra del Fuego. Boll. Accad. Gioenia Sci. Nat. Catania 1998, 30, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pilato, G.; Binda, M.G.; Qualtieri, F. Diphascon (Diphascon) mitrense, new species of eutardigrade from Tierra del Fuego. Boll. Sed. Accad. Gioenia di Sc. Nat. Catania 1999, 31, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rahm, G. Tardigrada of the South of America (esp. Chile). Rev. Chil. de Hist. Nat. 1931, 35, 118–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rahm, G. Freilebende Nematoden, Rotatorien und Tardigraden aus Südamerika (besondersaus Chile). Zool. Anz. 1932, 98, 94–128. [Google Scholar]

- Richters, F. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Moosfauna Australiens und der Inseln des Pacifischen Oceans. Zool. J. Abt. Syst. Geog. Biol. Tiere 1908, 26, 196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Roszkowska, M.; Ostrowska, M.; Kaczmarek, Ł. The genus Milnesium Doyere, 1840 (Tardigrada) in South America with descriptions of two new species from Argentina and discussion of the feeding behaviour in the family Milnesiidae. Zool. Stud. 2015, 54, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowska, M.; Stec, D.; Ciobanu, D.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Tardigrades from Nahuel Huapi National Park, Argentina, South America, with descriptions of two new Macrobiotidae species. Zootaxa 2016, 4105, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, R. A new species of Macrobiotus from Tierra del Fuego (Tardigrada: Macrobiotidae). Pan-Pacific Entomol. 1983, 59, 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Claps, M.; Rossi, G. Contribución al conocimiento de los tardígrados de Argentina. II. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Arg. 1981, 40, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Claps, M.; Rossi, G. Contribución al conocimiento de los tardígrados de Argentina. IV. Acta Zool. Lilloana 1984, 38, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Claps, M.; Rossi, G. Contribución al conocimiento de los tardígrados de Argentina. VI. Iheringia 1988, 67, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Claps, M. Contribución al conocimiento de los tardígrados de Argentina. I. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Arg. 1980, 39, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Claps, M. Tardígrados de la Argentina. V. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Arg. 1989, 47, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Claps, M. Tardígrados dulceacuícolas de la Argentina. In Fauna de Agua Duce de la República Argentina; Castellanos, Z.A., Ed.; Programa de Fauna de Agua Dulce: La Plata, Argentina, 1991; Volume 19, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Claps, M.; Rossi, G.; Ardohain, D. Tardigrada. In Biodiversidad de Artrópodos Argentinos; Claps, L.E., Debandi, G., Roig-Juñent, S., Eds.; Sociedad Entomológica Argentina: Mendoza, Argentina, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Claps, M.; Ardohain, D. Tardigrades from northwestern Patagonia, Neuquén Province, Argentina, with the description of three new species. Zootaxa 2009, 2095, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluffo, J.; Moly de Peluffo, M.; Rocha, A.M. Rediscovery of Echiniscus rufoviridis du Bois-Raymond Marcus 1944 (Heterotardigrada, Echiniscidae). New contributions to the knowledge of its morphology, bioecology and distribution. Gayana 2002, 66, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluffo, J.; Rocha, A.M.; Moly de Peluffo, M. Species diversity and morphometrics of tardigrades in a medium-sized city in the Neotropical region: Santa Rosa (La Pampa, Argentina). Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 30, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Moly de Peluffo, M.C.; Peluffo, J.R.; Rocha, A.M.; Doma, I.L. Tardigrade distribution in a medium-sized city of central Argentina. Hydrobiologia 2006, 558, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, R.; Peluffo, J.R.; Rocha, A.M.; Cesari, M.; Moly de Peluffo, M.C. The morphological and molecular analyses of a new South American urban tardigrade offer new insights on the biological meaning of the Macrobiotus hufelandi group of species (Tardigrada: Macrobiotidae). J. Nat. Hist. 2013, 47, 2409–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reyes, A.; Rocha, A.M.; Corronca, J.; Rodríguez-Artigas, S.; Doma, I.; Ostertag, B.; Grabosky, A. Effect of urbanization on the communities of tardigrades in Argentina. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 188, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.M.; Doma, I.L.; González-Reyes, A.; Lisi, O. Two new tardigrade species (Echiniscidae and Doryphoribiidae) from the Salta province (Argentina). Zootaxa 2020, 4878, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostertag, B.; Rocha, A.M.; González-Reyes, A.; Suárez, C.E.; Grabosky, A.; Doma, I.; Corronca, J. Effect of environmental an microhabitat variables on tardigrade communities in médium-sized city in central Argentina. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, S.J. Zoogeographic distribution of terrestrial/freshwater tardigrades from current literature. J. Nat. Hist. 1994, 28, 257–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.A. Terrestrial and freshwater Tardigrada of the Americas. Zootaxa 2013, 3747, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł.; McInnes, S.J. Annotated zoogeography of non-marine Tardigrada. Part II: South America. Zootaxa 2015, 3923, 1–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.M.; Izaguirre, M.F.; de Peluffo, M.C.M.; Peluffo, J.R.; Casco, V.H. Ultrastructure of the cuticle of Echiniscus rufoviridis [du Bois-Raymond Marcus, (1944) Heterotardigrada]. Acta Microsc. 2007, 16, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gąsiorek, P.; Morek, W.; Stec, D.; Michalczyk, Ł. Untangling the Echiniscus Gordian knot: Paraphyly of the “arctomys group” (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae). Cladistics 2019, 35, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorthouse, D.P. SimpleMappr, an Online Tool to Produce Publication-Quality Point Maps. 2010. Available online: http://www.simplemappr.net (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Gąsiorek, P. Water bear with barbels of a catfish: A new Asian Cornechiniscus (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae) illuminates evolution of the genus. Zool. Anz. 2022, 300, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsiorek, P.; Bochnak, M.; Vončina, K.; Michalczyk, Ł. Phenotypically exceptional Echiniscus species (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae) from Argentina (Neotropics). Zool. Anz. 2021, 294, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.M.; González-Reyes, A.; Ostertag, B.; Lisi, O. The genus Milnesium (Eutardigrada, Apochela, Milnesiidae) in Argentina: Description of three new species and key to the species of South America. Eur. J. Taxon. 2022, 822, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R.; Adkins Fletcher, R.; Guidetti, R.; Roszkowska, M.; Grobys, D.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Two new species of Tardigrada from moss cushions (Grimmia sp.) in a xerothermic habitat in northeast Tennessee (USA, North America), with the first identification of males in the genus Viridiscus. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Bois-Reymond Marcus, E. Sobre tardígrados brasileiros. Com. Zool. Mus. Hist. Nat. Montevideo 1944, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jörgensen, A. Graphical Presentation of the African Tardigrade Fauna using GIS with the Description of Isohypsibius malawiensis sp. n. (Eutardigrada: Hypsibiidae) from Lake Malawi. Zool. Anz. 2001, 240, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order, Family | Species | Type Locality | Endemic (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Antechiniscus jermani Rossi & Claps, 1989 | 41°11′ S, 71°49′ W, 1800 m asl: Río Negro Province, Nahuel Huapi National Park, Monte Tronador. | Y |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria bigranulata (Richters, 1907) | 54°48′ S, 68°18′ W, 50 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, Ushuaia. | N |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria paucigranulata Wilamowski, Vončina, Gąsiorek & Michalczyk, 2022 | 24°47′14″ S 65°43′30″ W, 2150 m asl: Salta Province, Rosario de Lerma Department. | Y |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Barbaria weglarskae Gąsiorek, Wilamowski, Vončina & Michalczyk, 2022 | 48°25′42″ S 71°44′48″ W, 803 m asl: Santa Cruz Province, vicinity of la Florida. | Y |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus aonikenk Gasiorek, Bochnak, Vončina & Michalczyk, 2021 | 44°10′26″ S 71°33′58″ W, 716 m asl: Patagonia, Chubut Province, vicinity of Río Pico. | Y |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Echiniscus pellucidus Gasiorek, Bochnak, Vončina & Michalczyk, 2021 | 44°10′26″ S 71°33′58″ W, 716 m asl: Patagonia, Chubut Province, vicinity of Río Pico. | Y |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Mopsechiniscus granulosus Mihelčič, 1967 | 41°14′ S, 71°46′ W; 800 m asl: Río Negro Province, Pampalinda, near Cainquenes stream. 41°58′ S, 71°31′ W, 390 m asl: Río Negro Province, Bolson. | N |

| Echiniscoidea, Echiniscidae | Pseudechiniscus (Meridioniscus) saltensis Rocha, Doma, González-Reyes & Lisi, 2020 | 24°27′–25°47′ S, 64°55′–65°40′ W, 1150 m asl: Salta Province, Salta City. | Y |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium argentinum Roszkowska, Ostrowska & Kaczmarek, 2015 | 41°13′ S, 71°27′ W, ca. 1200 m asl: Río Negro Province, Nahuel Huapi National Park. | Y |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium beatae Roszkowska, Ostrowska & Kaczmarek, 2015 | 41°12′ S, 71°50′ W, ca. 1000 m asl: Río Negro Province, Nahuel Huapi National Park. | Y |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium irenae Rocha, González-Reyes, Ostertag & Lisi, 2022 | 36°37′13″ S, 64°17′26″ W, ca 177 m asl: La Pampa Province, Santa Rosa City. | Y |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium pelufforum Rocha, González-Reyes, Ostertag & Lisi, 2022 | 24°47′18″ S, 65°24′38″ W, 1150 m asl: Salta Province, Salta City. | Y |

| Apochela, Milnesiidae | Milnesium quiranae Rocha, González-Reyes, Ostertag & Lisi, 2022 | 24°47′18″ S, 65°24′38″ W, 1150 m asl: Salta Province, Salta City. | Y |

| Parachela, Doryphoribiidae | Doryphoribius cephalogibbosus (Rocha, Doma, González-Reyes & Lisi, 2020) | 24°27′–25°47′ S, 64°55′–65°40′ W, 1150 m asl: Salta Province, Salta City. | Y |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Diphascon mitrense Pilato, Binda & Qualtieri, 1999 | 54°47′ S, 68°16′ W; 100 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Península Mitre, Estancia Río Pipo. | Y |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Hypsibius marcelli Pilato, 1990 | 52°54′ S, 68°27′ W, 0 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, near Estancia Cullen. | Y |

| Parachela, Hypsibiidae | Mixibius fueginus Pilato & Binda, 1996 | 54°47′ S, 68°24′ W, 650 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, San Martial Glacier. | Y |

| Parachela, Isohypsibiidae | Ursulinius tucumanensis (Claps & Rossi, 1984) | 26°47′ S, 65°20′ W, 750 m asl: Tucumán Province, Horco Molle. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus anderssoni Richters, 1908 | 54°48′ S, 68°18′ W, 50 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, Ushuaia, valley. 54°46′ S, 68°12′ W, 150 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, Río Olivia. 54°47′ S, 68°23′ W, 800 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, mountain region of Ushuaia. 54°50′ S, 68°34′ W, 0 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Tierra Mayor (Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego), near Roca Lake. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus andinus Maucci, 1988 | 50°06′ S, 73°18′ W, 200 m asl: Santa Cruz Province, Los Glaciares National Park, shores of Argentino Lake, near Onelli Glacier. | N |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus kazmierskii Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2009 | 41°11.551′ S, 71°49.908′ W/41°12′N, 71°50′ W, 1100 m asl: Río Negro Province, Nahuel Huapi National Park, Ventisquero Negro. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus kristenseni Guidetti, Peluffo, Rocha, Cesari & Moly de Peluffo, 2013 | 35°40′ S, 63°44′ W; 143 m asl: La Pampa Province, General Pico (125 km northeast of Santa Rosa). 36°39′ S, 64°17′ W; 177 m asl: La Pampa Province, Santa Rosa City. 36°55′ S, 64°16′ W; 150 m asl: La Pampa Province, Reserve Provincial Parque Luro (35 km south of Santa Rosa). | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus papillosus Iharos, 1963 | 41°59′ S, 71°31′ W, 360 m asl: Río Negro Province, El Bolsón, Mt. Piltriquitron. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Macrobiotus patagonicus Maucci, 1988 | 50°06′ S, 73°18′ W, 200 m asl: Santa Cruz Province, Los Glaciares National Park, shores of Argentino Lake, near Onelli Glacier. | N |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus neuquensis Rossi, Claps & Ardohain, 2009 | 40°07′ S, 71°39′ W, 700 m asl: Neuquén Province, Hua Hum, Junín de los Andes. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus ovostriatus (Pilato & Patanè, 1998) | 54°17′ S, 66°42′ W, 50 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, Península Mitre, Cabo San Pablo. 54°47′ S, 68°16′ W, 100 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Peninsula Mitre, Río Pipo. | N |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus pseudoblocki Roszkowska, Stec, Ciobanu & Kaczmarek, 2016 | 41°12′ S, 71°50′ W, ca. 1000 m asl: Río Negro, Nahuel Huapi National Park, Ventisquero Negro. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus szeptyckii (Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2009) | 41°31′ S, 71°30′ W, 950 m asl: Río Negro Province, Nahuel Huapi National Park, 70 km south of San Carlos de Bariloche. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Mesobiotus tehuelchensis (Rossi, Claps & Ardohain, 2009) | 39°08′ S, 71°17′ W, 1000 m asl: Neuquén Province, Aluminé Ñorquinco Lake. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus claxtonae Rossi, Claps & Ardohain, 2009 | 39°25′ S, 71°17′ W, 1000 m asl: Neuquén Province, Aluminé, Quillén Lake. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Minibiotus pseudostellarus Roszkowska, Stec, Ciobanu & Kaczmarek, 2016 | 41°12′ S, 71°51′ W, ca. 1200 m asl: Río Negro Province, Nahuel Huapi National Park, Bariloche, at the foot of the Tronador volcano, Garganta del Diablo waterfall. | Y |

| Parachela, Macrobiotidae | Schusterius tridigitus (Schuster, 1983) | 54°47′ S, 68°24′ W, 600–750 m asl: Tierra del Fuego Province, Sierra Martial. | Y |

| Parachela, Ramazzottiidae | Ramazzottius saltensis Claps & Rossi, 1984 | 24°55′ S, 64°09′ W, 400 m asl: Salta Province, road from Las Lajitas to J.V. González. | Y |

| Characters | Image Type | Figures of the Genus Viridiscus | Figures of B. cf. rufoviridis comb. nov. (Argentine Material) | Figures of the Genus Barbaria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuticular ornamentation | PCM | 4e, 5e, 6f in Gąsiorek et al. [48] | 1–2 in Peluffo et al. [37] | 4a, 5a, 6a in Gąsiorek et al. [48] 2, 6, 13, 15, 25 in Michalczyk & Kaczmarek [15] |

| SEM | 7d in Gąsiorek et al. [48] | 3–5 in Peluffo et al. [37] | 3–4; 9–10; 14, 16, 23 in Michalczyk & Kaczmarek [15] | |

| Cuticle structure | SEM | - | - | 11–12, 53–54 in Michalczyk & Kaczmarek [15] |

| TEM | - | 1–2 in Rocha et al. [47] | - | |

| drawings | - | - | 72–74 in Michalczyk & Kaczmarek [15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rocha, A.; Camarda, D.; Ostertag, B.; Doma, I.; Meier, F.; Lisi, O. Actual State of Knowledge of the Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrade Fauna of the Republic of Argentina and New Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944). Diversity 2023, 15, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020222

Rocha A, Camarda D, Ostertag B, Doma I, Meier F, Lisi O. Actual State of Knowledge of the Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrade Fauna of the Republic of Argentina and New Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944). Diversity. 2023; 15(2):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020222

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocha, Alejandra, Daniele Camarda, Belen Ostertag, Irene Doma, Florencia Meier, and Oscar Lisi. 2023. "Actual State of Knowledge of the Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrade Fauna of the Republic of Argentina and New Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944)" Diversity 15, no. 2: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020222

APA StyleRocha, A., Camarda, D., Ostertag, B., Doma, I., Meier, F., & Lisi, O. (2023). Actual State of Knowledge of the Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrade Fauna of the Republic of Argentina and New Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois-Reymond Marcus, 1944). Diversity, 15(2), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020222