Factors Affecting Plant Composition in Abandoned Railway Areas with Particular Emphasis on Forest Proximity

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Which species dominate in the abandoned railway areas and what are their habitat preferences?

- After what amount of time do forest communities develop in this type of habitat?

- What environmental factors accelerate the rate of forest community formation?

2. Materials and Methods

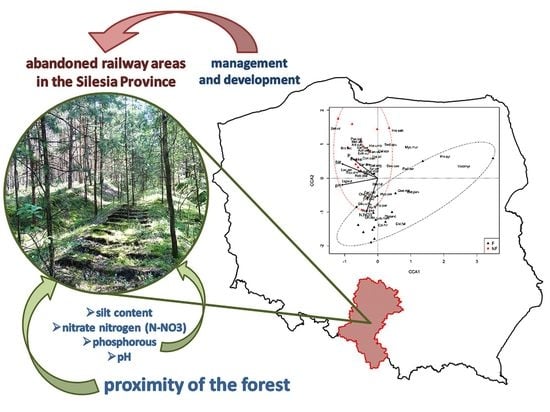

2.1. Study Area

2.2. The Field Research

2.3. Soil Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Abbreviations: The following Abbreviations Have Been Used in this Paper

- Life strategy: C—competitor, S—stress tolerator, R—ruderal, CR—competitive ruderal, CS—stress tolerant competitor, SR—stress tolerant ruderal, CSR—intermediate;

- Selected ecological indicators: L—light, T—temperature, R—soil reaction;

- Species names: Ace.pla—Acer platanoides, Ace.pse—Acer pseudoplatanus, Ach.mil—Achillea millefolium, Aeg.pod—Aegopodium podagraria, Arr.ela—Arrhenatherum elatius, Art.vul—Artemisia vulgaris, Bet.pen—Betula pendula, Bra.rut—Brachythecium rutabulum, Bra.sal—Brachythecium salebrosum, Bro.tec—Bromus tectorum, Bry.cae—Bryum caespiticium, Cal.epi—Calamagrostis epigejos, Cal.sep—Calystegia sepium, Car.are—Cardaminopsis arenosa, Cer.hol—Cerastium holosteoides, Cer.pur—Ceratodon purpureus, Che.maj—Chelidonium majus, Con.arv—Convolvulus arvensis, Con.can—Conyza canadensis, Dau.car—Daucus carota, Des.ces—Deschampsia caespitosa, Did.fal—Didymodon fallax, Dry.car—Dryopteris carthusiana, Dry.fil—Dryopteris filix—mas, Ech.cru—Echinochloa crus—galli, Ech.vul—Echium vulgare, Epi.hel—Epipactis helleborine, Epi.hir—Epilobium hirsutum, Equ.arv—Equisetum arvense, Equ.syl—Equisetum sylvaticum, Eri.ann—Erigeron annuus, Eup.can—Eupatorium cannabinum, Fra.aln—Frangula alnus, Fra.exc—Fraxinus excelsior, Gal.ang—Galeopsis angustifolia, Gal.mol—Galium mollugo, Ger.rob—Geranium robertianum, Geu.urb—Geum urbanum, Hie.pil—Hieracium pilosella, Hie.sab—Hieracium sabaudum, Hie.umb—Hieracium umbellatum, Hyp.per—Hypericum perforatum, Imp.par—Impatiens parviflora, Lac.ser—Lactuca serriola, Lam.mac—Lamium maculatum, Lat.syl—Lathyrus sylvestris, Lig.vul—Ligustrum vulgare, Lin.vul—Linaria vulgaris, Lot.cor—Lotus corniculatus, Lys.num—Lysimachia nummularia, Med.lup—Medicago lupulina, Med.sat—Medicago sativa, Mel.alb—Melilotus alba, Myc.mur—Mycelis muralis, Oen.bie—Oenothera biennis, Pad.ser—Padus serotina, Pas.sat—Pastinaca sativa, Pim.sax—Pimpinella saxifraga, Pin.syl—Pinus sylvestris, Pla.lan—Plantago lanceolata, Pla.maj—Plantago major, Pla.und—Plagiomnium undulatum, Poa.ann—Poa annua, Poa.com—Poa compressa, Poa.pra—Poa pratensis, Que.rob—Quercus robur, Res.lut—Reseda lutea, Rob.ps—Robina pseudoacacia, Rub.cae—Rubus caesius, Rub.ida—Rubus idaeus, Rub.pli—Rubus plicatus, Rub.wim—Rubus wimmerianus, Rum.ace—Rumex acetosa, Sam.nig—Sambucus nigra, Scl.ann—Scleranthus annuus, Sed.spu—Sedum spurium, Set.vir—Setaria viridis, Sil.vul—Silene vulgaris, Sol.can—Solidago canadensis, Sol.gig—Solidago gigantea, Ste.med—Stellaria media, Tan.vul—Tanacetum vulgare, Tar.off—Taraxacum officinale, Tor.jap—Torilis japonica, Tri.arv—Trifolium arvense, Urt.dio—Urtica dioica, Vac.myr—Vaccinium myrtillus, Ver.cha—Veronica chamaedrys, Vic.cra—Vicia cracca, Vio.rei—Viola reichenbachiana.

3. Results

3.1. Flora and Vegetation

3.2. Soil Properties

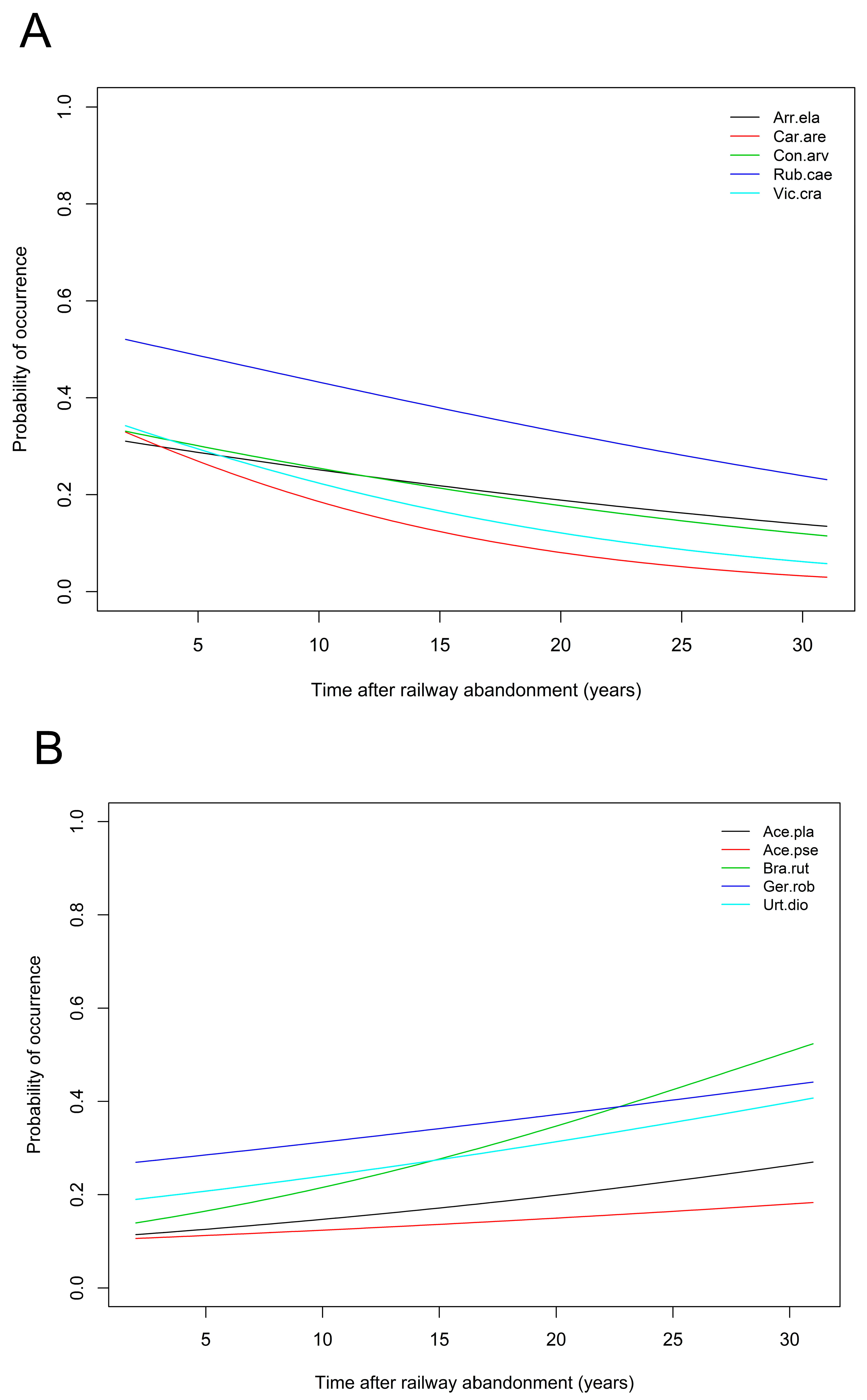

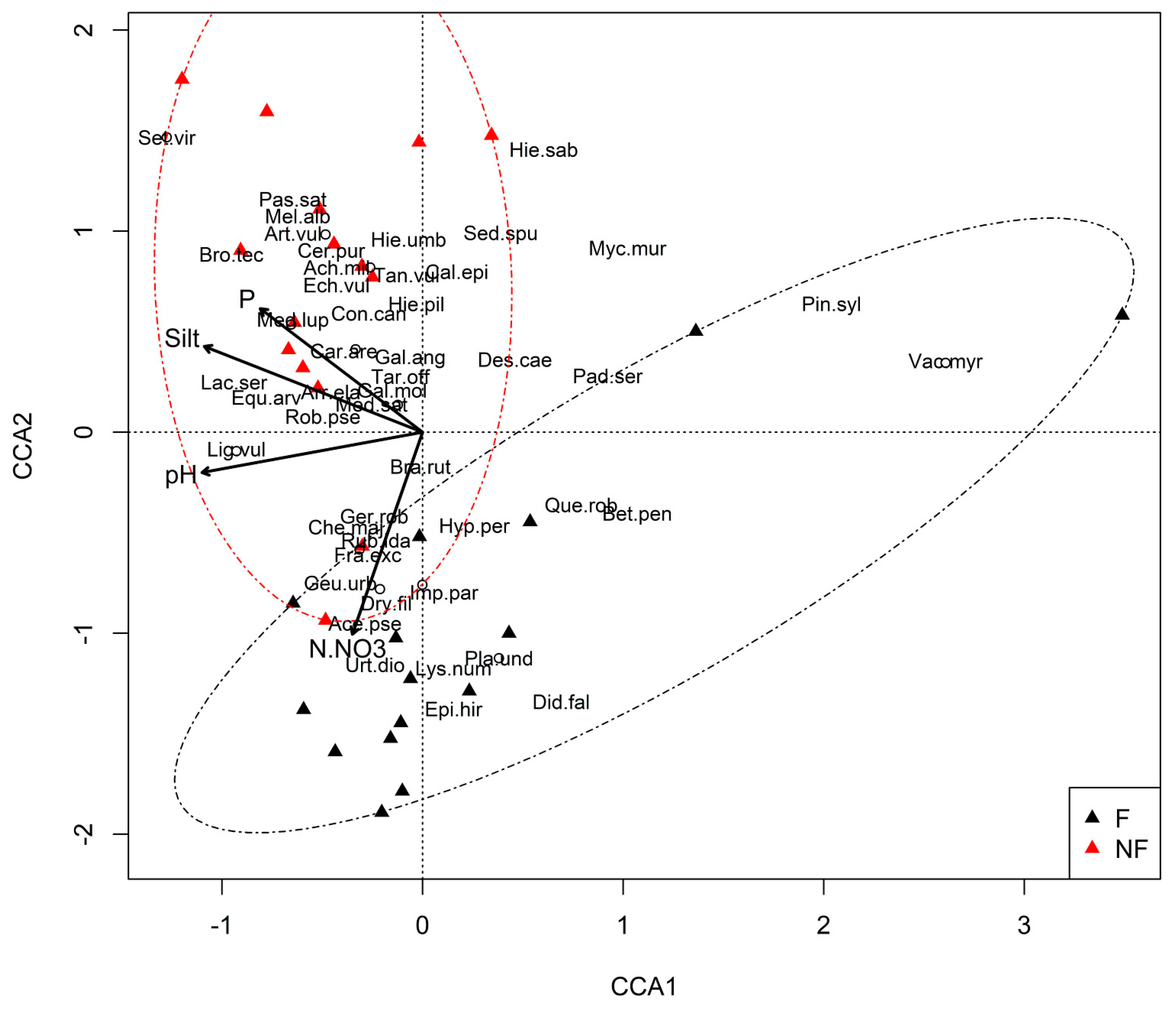

3.3. Plant Communities and Their Relationships with the Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The type of plant communities occurring in the immediate vicinity of the abandoned railway lines has a major impact on which species dominate in the developing communities. In the vicinity of forests, these are acidophilous, CS and SR strategies, zoochorous, and shade-tolerant species, whereas basiphilous, CR strategies, anemochorous, heliophilous, and species that prefer loamy soils dominate when a given area is surrounded by non-forest communities.

- The proximity of forested areas determinates a higher rate of succession towards forest communities. A similar role is played by grain-size composition of the soil; the process is faster on sandy soils. Other soil parameters (except pH, nitrate nitrogen, and phosphorous content) are of relatively minor importance.

- Forest communities may develop on abandoned railway areas after several years provided there are forests growing in their vicinity. However, these are synanthropic communities whose herb layer significantly deviates from typical forests.

- The obtained results can be used by various institutions dealing with managing and developing of such areas to revitalize them.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faliński, J.B. Sukcesja roślinności na nieużytkach porolnych jako przejaw dynamiki ekosystemu wyzwolonego spod długotrwałej presji antropogenicznej [The succession of vegetation on agricultural wastelands as a manifestation of the dynamics of the ecosystem liberated from long-term anthropogenic pressure]. Wiadomości Bot. 1986, 30, 25–50. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Clements, F.E. Plant Succession: An Analysis of the Development of Vegetation; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 1916; pp. 1–512. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, F.E. Plant Succession and Indicators: A Definitive Edition of Plant Succession and Plant Indicators; The H.W. Wilson Company: New York, NY, USA, 1928; pp. 1–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, H.A. The individualistic concept of the plant association. Am. Midl. Nat. 1939, 21, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzaz, F.A. Succession on abandoned fields in the Shawnee Hills, Southern Illinois. Ecology 1968, 49, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, H.S. The ecology of secondary succession. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1974, 5, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegan, B. Forest succession. Nature 1984, 312, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Collins, S.L.; Armesto, J.J. A hierarchical consideration of causes and mechanisms of succession. Vegetatio 1987, 69, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Collins, S.L.; Armesto, J.J. Models, Mechanisms and Pathways of Succession. Bot. Rev. 1987, 53, 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn-Lewin, D.C.; Peet, R.K.; Veblen, T.T. (Eds.) Plant Succession. Theory and Prediction; Chapman & Hall: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 1–352. [Google Scholar]

- Botkin, D.B. Forest Dynamics—An Ecological Model; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 1–309. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegleb, G.; Felinks, B. Primary succession in post-mining landscapes of Lower Lusatia—Chance or necessity. Ecol. Eng. 2001, 17, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipperer, W.C. The process of natural succession in urban areas. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology; Douglas, I., Goode, D., Houck, M., Wang, R., Eds.; Routledge Press: London, UK, 2011; pp. 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Turner, B.L. Ecological succession in a changing world. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantz, H.L. Plant Succession on Abandoned Roads in Eastern Colorado. J. Ecol. 1917, 5, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roux, E.R.; Warren, M. Plant Succession on abandoned fields in central Oklahoma and in the Transvaal Highveld. Ecology 1963, 44, 576–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, D. Flora und Vegetation der Bahnhöfe Mitteleuropas. Phytocoenologia 1983, 11, 31–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, D. Eisenbahnanlagen als Untersuchungsgegenstand der Geobotanik. Tuexenia 1993, 13, 415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I.; Tietz, B. Soils on ruined railway stations—The Anhalter Güterbahnhof. In XIII Congress of the International Society of Soil Science (Hamburg, Germany)—Guidebook Tours G and H: Soilscapes of Berlin (West): Natural and Anthropogenic Soils and Environmental Problems within a Metropolitan Area; Alaily, F., Grenzius, R., Renger, M., Stahr, K., Tietz, B., Wessolek, G., Eds.; Mitteilungen Deutsche Hamburg, Germany Bodenkundliche Gesellschaft 50; 1986; pp. 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I.; Langer, A. Vegetation einer Berliner Eisenbahnfläche (Schöneberger Südgelände) im vierten Jahrzehnt der Sukzession. Verh. Der Bot. Ver. Berl. Brandenbg. 1994, 127, 5–43. [Google Scholar]

- Prach, K.; Pyšek, P.; Šmilauer, P. Prediction of vegetation succession in human disturbed habitats using an expert system. Restor. Ecol. 1999, 7, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Pyšek, P.; Bastl, M. Spontaneous vegetation succession in human-disturbed habitats: A pattern across seres. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2001, 4, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Lencová, K.; Řehounková, K.; Dvořáková, H.; Jírová, A.; Konvalinková, P.; Mudrák, O.; Novák, J.; Trnková, R. Spontaneous vegetation succession at different central European mining sites: A comparison across seres. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 7680–7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinninger, I.; Maier, R.; Punz, W. Der stillgelegte Frachtenbahnhof Wien-Nord Standortbedingungen und ökologische Charakteristik der Gefäßpflanzen einer Bahnbrache. Verh. Der Zool. Bot. Ges. Osterr. 2002, 139, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Galera, H.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Wierzbicka, M.; Wiłkomirski, B. Encroachment of forest species into operating and abandoned railway areas in north-eastern Poland. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomakis, N.; Ganatsas, P. Land cover changes and forest succession trends in a site of Natura 2000 network (Elatia forest), in northern Greece. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2012, 285, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Z. Rozwój i Regres Sieci Kolejowej w Polsce [The Growth and Contraction of the Railway Network in Poland]; Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland; Stanisław Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization: Warsaw, Poland, 2007; Monographies 7; pp. 1–322. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesień, M.; Denisow, B.; Mamchur, Z.; Chuba, M.; Resler, I. Composition and structure of the flora in intra-urban railway areas. Acta Agrobot. 2016, 69, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulias, R.; Hibszer, A. Województwo Śląskie—Przyroda, Gospodarka, Dziedzictwo Kulturowe [Silesian Voivodeship—Nature, Economy, Cultural Heritage]; Wydawnictwo Kubajak: Krzeszowice, Poland, 2004; pp. 9, 41–43, 141–142. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Galera, H.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Wierzbicka, M.; Wiłkomirski, B. Directions of changes in the flora structure in the abandoned railway areas. Ecol. Quest. 2012, 16, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Piskorz, R.; Czarna, A. Vascular plants on active and closed railway stations in Wolsztyn and its surroundings. Rocz. Akad. Rol. Pozn. Bot. Stec. 2006, 10, 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesień, M.; Święs, F. Flora i Zbiorowiska Roślinne Terenów Kolejowych Zachodniej Części Wyżyny Lubelskiej [Flora and Vascular Plants Communities of Railway Areas of the Western Part of the Lublin Upland]; Wydawnictwo UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2006; pp. 1–255. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, Å. On the railway vegetation and flora between Esbo and lngå, S. Finland. Acta Bot. Fenn. 1969, 83, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, C. Britain’s Railway Vegetation; Institute of Terrestrial Ecology: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jehlík, V. The Vegetation of Railways in Northern Bohemia (Eastern Part); Academia Publishing House of the Czechoslovak: Prague, Czech Republic; Academy of Sciences: Prague, Czech Republic, 1986; Vegetace ČSSR, ser. A, 14; pp. 1–366. [Google Scholar]

- Jandová, L.; Sklenář, P.; Kovář, P. Changes of Grassland Vegetation in Surroundings of New Railway Flyover (Eastern Bohemia, Czech Republic). Part I: Plant Communities and Permanent Habitat Plots. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 2, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Májeková, J.; Letz, D.R.; Slezák, M.; Zaliberová, M.; Hrivnák, R. Rare and threatened vascular plants of the railways in Slovakia. Biodivers. Res. Conserv. 2014, 35, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Májeková, J.; Zaliberová, M.; Andrik, E.J.; Protopopova, V.V.; Shevera, M.V.; Ikhardt, P. A comparison of the flora of the Chop (Ukraine) and Čierna nad Tisou (Slovakia) border railway stations. Biologia 2020, 76, 1969–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, V.; Ozyigit, I.I.; Osma, E.; Bakir, Y.; Demir, G.; Severoglu, Z.; Yarci, C. Environmental relationships of the vascular flora alongside the railway tracks between Haydarpaşa and Gebze (Istanbul-Kocaeli/ Turkey). J. Environ. Biol. 2015, 36, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Denisow, B.; Wrzesień, M.; Mamchur, Z.; Chuba, M. Invasive flora within urban railway areas: A case study from Lublin (Poland) and Lviv (Ukraine). Acta Agrobot. 2017, 70, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornaś, J.; Leśniowska, I.; Skrzywanek, A. Observations on the flora of railway areas and freight stations in Cracow. Fragm. Florist. Geobot. Pol. 1959, 5, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka, M.; Galera, H.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Wiłkomirski, B. Geranium robertianum L., plant form adapted to the specific conditions along railway: ”Railway-wandering plant”. Plant Syst. Evol. 2014, 300, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Impact of road construction on vegetation alongside Quinghai-Xizang highway and railway. Chinese Geogr. Sci. 2003, 13, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikka, P.M.; Högmander, H.; Koski, P.S. Road and railway verges serve as dispersal corridors for grassland plants. Landsc. Ecol. 2001, 16, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Wysocki, C. Flora nasypu nieużytkowanej linii kolejowej w okolicach Sokołowa Podlaskiego [Flora of a non-used railway embankment near Sokołów Podlaski]. Woda Sr. Obsz. Wiej. 2010, 10, 85–94. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kryszak, A.; Kryszak, J.; Czemko, M.; Kalbarczyk, M. Vegetation of embankment along selected railway lines. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Przyr. We Wrocławiu. Rol. 2006, 88, 159–164. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Suominen, J. The plant cover of Finnish railway embankments and the ecology of their species. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1969, 6, 183–235. [Google Scholar]

- Hutniczak, A.; Urbisz, A.; Wilczek, Z. Flora i Roślinność Nieużytkowanych Terenów Kolejowych Województwa Śląskiego [Flora and Vegetation of Abandoned Railway Areas of the Silesian Province]; Monographs of the Upper Silesian Museum 15; Muzeum Górnośląskie: Bytom, Poland, 2020; pp. 1–130. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Galera, H.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Wierzbicka, M.; Jarzyna, I.; Wiłkomirski, B. Structure of the flora of railway areas under various kinds of anthropopression. Pol. Bot. J. 2014, 59, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Yearbook of Śląskie Voivodship. 2020. Available online: https://katowice.stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/katowice/en/defaultaktualnosci/665/1/20/1/rocznik_2020_internet_wersja_angielska.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Stankiewicz, R.; Stiasny, M. Atlas Linii Kolejowych Polski 2014 [Atlas of Polish Railway Lines 2014]; Eurosprinter Publisher: Rybnik, Poland, 2014; pp. 1–464. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ogólnopolska Baza Kolejowa [National Railway Database]. Available online: https://www.bazakolejowa.pl/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie, Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde, 3rd ed.; (Phytosociology, the Basis of Vegetation Science); Springer: Wien, Austria; New York, NY, USA, 1964; Volume 3, pp. 1–865. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Maarel, E. Transformation of Cover-Abundance Values in Phytosociology and Its Effects on Community Similarity. Vegetatio 1979, 39, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszkiewicz, W. Przewodnik do Oznaczania Zbiorowisk Roślinnych Polski [Guide to the Determination of Polish Plant Communities]; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 1–536. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mirek, Z.; Piękoś-Mirkowa, H.; Zając, A.; Zając, M. Vascular Plants of Poland. An Annotated Checklist; W. Szafer Institute of Botany: Krakow, Poland; Polish Academy of Sciences: Cracow, Poland, 2020; pp. 1–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ochyra, R.; Żarnowiec, J.; Bednarek-Ochyra, H. Census Catalogue of Polish Mosses; Institute of Botany: Kraków, Poland; Polish Academy of Sciences: Cracow, Poland, 2003; pp. 1–372. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska-Guzik, B.; Dajdok, Z.; Zając, M.; Zając, A.; Urbisz, A.; Danielewicz, W.; Hołdyński, C. Rośliny Obcego Pochodzenia w Polsce ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Gatunków Inwazyjnych [Plants of Foreign Origin in Poland, with Particular Emphasis on Invasive Species]; Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 1–196. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki, K.; Trzcińska-Tacik, H.; Różański, W.; Szeląg, Z.; Wołek, J.; Korzeniak, U. Ecological Indicator Values of Vascular Plants of Poland; W. Szafer Institute of Botany: Kraków, Poland; Polish Academy of Sciences: Cracow, Poland, 2002; pp. 1–183. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.; Klotz, S. Biologisch-Ökologische Daten zur Flora der DDR, 2nd ed.; Martin Luther Universität Halle—Wittenberg Wissenschaftliche Beiträge: Halle, Germany, 1990; pp. 33–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg, H.; Leuschner, C. Zeigerwerte der Pflanzen Mitteleuropas. In Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen, 6th ed.; Verlag Eugen Ulmer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ryżak, M.; Bartmiński, P.; Bieganowski, A. Metody wyznaczania rozkładu granulometrycznego gleb mineralnych [Methods for determining the granulometric distribution of mineral soils]. Acta Agrophysica Rozpr. I Monogr. 2009, 4, 1–84. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna. Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Messenger, K.G. A railway flora of Rutland. Proc. Bot. Soc. Br. Isl. 1968, 7, 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Galera, H.; Suska-Malawska, M.; Staszewski, T.; Wiłkomirski, B. Specyfika grupy najpospolitszych gatunków we florze silnie skażonych odcinków torowisk kolejowych w północno-wschodniej Polsce (Mazury i Podlasie) [Specificity of the most common species in the flora of extremely contaminated sections of the railway tracks in north-eastern Poland (Warmian—Masurian and Podlasie Provinces)]. Monit. Sr. Przyr. 2014, 15, 59–73. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Partzsch, M.; Kästner, A. Flora und Vegetetion an Straßenrändern und Bahndämmen im Kreis Kötchen (Sachsen-Anhalt). Hercynia Okol. Umw. Mitteleur. 1995, 29, 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes, D. Vascular Flora of the Lüchow Railway Station (Lower Saxony, Germany). Available online: http://www.ruderal-vegetation.de/epub/vascular.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Murray, P.; Ge, Y.; Hendershot, W.H. Evaluating three trace metal contaminated sites: A field and laboratory investigation. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 107, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukopp, H. (Ed.) Stadtökologie. Das Beispiel Berlin; Reimer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1990; pp. 1–455. [Google Scholar]

- Heneidy, S.Z.; Halmy, M.W.A.; Toto, S.M.; Hamouda, S.K.; Fakhry, A.M.; Bidak, L.M.; Eid, E.M.; Al-Sodany, Y.M. Pattern of Urban Flora in Intra-City Railway Habitats (Alexandria, Egypt): A Conservation Perspective. Biology 2021, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plot No. | Coordinates | Railway Line No. | Locality | No. of Years after the Abandonment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest plots (F) | ||||

| F1 | 49°44′21″ N; 18°44′15″ E | 190 | Goleszów | 7 |

| F2 | 50°13′12″ N; 18°59′37″ E | 653 | Katowice Ochojec | 2 |

| F3 | 50°33′13″ N; 18°37′2″ E | 684 | Krupski Młyn | 3 |

| F4 | 50°05′49″ N; 18°15′48″ E | 176 | Racibórz Markowice | 3 |

| F5 | 50°33′06″ N; 18°37′34″ E | 684 | Borowiany | 3 |

| F6 | 50°23′58″ N; 18°43′38″ E | 178 | Kamieniec | 16 |

| F7 | 49°57′20″ N; 18°36′56″ E | 159 | Jastrzębie-Zdrój Górne | 11 |

| F8 | 49°57′25″ N; 18°35′44″ E | 159 | Jastrzębie-Zdrój Górne | 11 |

| F9 | 49°56′02″ N; 18°31′59″ E | 159 | Jastrzębie-Zdrój Szotkowice | 14 |

| F10 | 50°21′19″ N; 19°14′00″ E | 662 | Dąbrowa Górnicza Piekło | 16 |

| F11 | 50°32′52″ N; 18°37′28″ E | 683 | Czarków | 31 |

| F12 | 50°03′08″ N; 18°09′32″ E | 193 | Wojnowice | 22 |

| F13 | 50°10′39″ N; 18°46′46″ E | 172 | Ornontowice | 21 |

| F14 | 50°20′46″ N; 18°52′55″ E | 710 | Bytom Bobrek | 26 |

| F15 | 50°20′05″ N; 18°48′49″ E | 132 | Zabrze Biskupice | 17 |

| Non-forest plots (NF) | ||||

| NF16 | 49°45′02″ N; 18°38′32″ E | 190 | Cieszyn | 7 |

| NF17 | 49°47′51″ N; 18°48′08″ E | 190 | Skoczów | 4 |

| NF18 | 50°00′15″ N; 18°18′56″ E | 176 | Syrynia | 3 |

| NF19 | 50°02′39″ N; 18°17′03″ E | 176 | Lubomia | 3 |

| NF20 | 50°06′31″ N; 18°15′58″ E | 176 | Racibórz Markowice | 3 |

| NF21 | 49°57′16″ N; 18°34′48″ E | 159 | Jastrzębie-Zdrój | 11 |

| NF22 | 49°56′15″ N; 18°32′42″ E | 159 | Jastrzębie-Zdrój Moszczenica | 14 |

| NF23 | 50°20′25″ N; 19°13′11″ E | 162 | Dąbrowa Górnicza Gołonóg | 16 |

| NF24 | 50°24′40″ N; 18°34′25″ E | 152 | Paczyna | 16 |

| NF25 | 50°24′35″ N; 18°34′34″ E | 152 | Paczyna | 16 |

| NF26 | 50°12′00″ N; 18°45′34″ E | 172 | Chudów | 21 |

| NF27 | 50°04′09″ N; 18°11′41″ E | 193 | Racibórz Studzienna | 22 |

| NF28 | 50°01′29″ N; 18°08′24″ E | 193 | Krzanowice | 22 |

| NF29 | 50°20′37″ N; 18°46′33″ E | 132 | Zabrze Mikulczyce | 17 |

| NF30 | 50°11′42″ N; 18°45′51″ E | 172 | Chudów | 21 |

| Parameter | Unit of Measure | Study Method |

|---|---|---|

| pH in H2O | - | Potentiometric method |

| Electrical conductivity | µS/cm | Conductometric method |

| Dry matter | % | Gravimetric method |

| Organic matter | %dw | Gravimetric method |

| Total organic carbon (TOC) | %dw | Titrimetric method |

| Humus horizon | %dw | Tiurin’s method |

| Total Kjeldahl nitrogen | mg kg−1dw | Titrimetric method |

| Ammonia nitrogen/N-NH4/ | mg kg−1dw | Continuous flow analysis (CFA) with spectrophotometric detection |

| Nitrate nitrogen/N-NO3/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Calcium/Ca/ | mg kg−1dw | Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) |

| Magnesium/Mg/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Potassium/K/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Sodium/Na/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Total phosphorus/P/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Zinc /Zn/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Copper/Cu/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Lead/Pb/ | mg kg−1dw | |

| Iron/Fe/ | mg kg−1dw |

| F (n = 15) | NF (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Species richness | 10.33 ± 4.94 | 10.93 ± 4.93 |

| Species diversity (S-W index) | 1.93 ± 0.47 | 1.99 ± 0.49 |

| Vegetation cover (%) | 88.00 ± 20.07 | 94.67 ± 8.96 |

| Moss cover (%) * | 19.53 ± 35.44 | 6 ± 11.05 |

| Native species | 7.67 ± 4.65 | 8.33 ± 3.06 |

| Anthropophytes | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 2 ± 2.51 |

| Archaeophytes | 0.27 ± 0.7 | 0.87 ± 1.88 |

| Kenophytes | 1.33 ± 1.05 | 1.13 ± 1.19 |

| Invasive species | 1.2 ± 0.94 | 0.67 ± 0.98 |

| Phanerophytes * | 2.67 ± 1.8 | 1.2 ± 0.77 |

| Chamaephytes | 0.4 ± 0.83 | 0.33 ± 0.62 |

| Hemicryptophytes | 3.27 ± 2.52 | 5.53 ± 4.26 |

| Cryptophytes | 0.33 ± 0.62 | 0.67 ± 0.72 |

| Therophytes | 0.87 ± 0.74 | 1.4 ± 1.59 |

| C strategy | 4.73 ± 2.66 | 5.13 ± 2.39 |

| R strategy | 0.4 ± 0.63 | 0.6 ± 0.83 |

| S strategy | 0 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.35 |

| CR strategy ** | 0.53 ± 0.74 | 2.4 ± 1.99 |

| CS strategy * | 0.8 ± 1.08 | 0.2 ± 0.41 |

| SR strategy * | 0.53 ± 0.52 | 0.13 ± 0.35 |

| CSR strategy | 2.27 ± 2.19 | 1.67 ± 1.68 |

| Anemochory | 3.93 ± 3.08 | 4.67 ± 2.72 |

| Autochory | 1.27 ± 0.59 | 1 ± 0.93 |

| Zoochory | 3.13 ± 1.68 | 2.27 ± 1.03 |

| Parameter | F (n = 15) | NF (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| pH (H2O) | 7.19 ± 0.59 | 7.37 ± 0.36 |

| EC | 108.90 ± 68.64 | 88.32 ± 52.68 |

| Dry weight (%) | 72.61 ± 11.57 | 80.04 ± 5.12 |

| Org. matter (%) | 17.34 ± 10.29 | 11.14 ± 4.59 |

| TOC (%) | 10.74 ± 7.03 | 6.44 ± 3.32 |

| Humus (%) | 18.62 ± 12.07 | 11.13 ± 5.81 |

| N (mg kg−1) | 3453.33 ± 3545.19 | 3060 ± 1277.16 |

| N-NH4 (mg kg−1) | 29.22 ± 21.87 | 17.14 ± 8.52 |

| N-NO3 (mg kg−1) | 23.77 ± 26.52 | 9.87 ± 11.52 |

| Ca (mg kg−1) | 21,824.27 ± 21,536.34 | 24,701.27 ± 30,995.31 |

| Mg (mg kg−1) | 8125.33 ± 5284.16 | 6193.67 ± 3018.39 |

| K (mg kg−1) | 1310.40 ± 745.16 | 1687.73 ± 1247.96 |

| Na (mg kg−1) | 465.53 ± 381.08 | 406.53 ± 150.99 |

| Zn (mg kg−1) | 1626.93 ± 2002.98 | 855.13 ± 1192.72 |

| Cu (mg kg−1) | 435.82 ± 397.17 | 776.57 ± 1295.32 |

| Pb (mg kg−1) | 334.93 ± 357.57 | 252.23 ± 296.19 |

| Fe (mg kg−1) | 57,092.67 ± 16,517.47 | 71,488.67 ± 42,389.94 |

| P (mg kg−1) * | 1051.53 ± 409.41 | 2152.60 ± 2312.09 |

| Clay (%) * | 0.27 ± 0.59 | 0.80 ± 0.86 |

| Silt (%) ** | 21.33 ± 10.61 | 30.40 ± 6.85 |

| Sand (%) ** | 78.4 ± 10.99 | 68.80 ± 6.30 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hutniczak, A.; Urbisz, A.; Urbisz, A.; Strzeleczek, Ł. Factors Affecting Plant Composition in Abandoned Railway Areas with Particular Emphasis on Forest Proximity. Diversity 2022, 14, 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121141

Hutniczak A, Urbisz A, Urbisz A, Strzeleczek Ł. Factors Affecting Plant Composition in Abandoned Railway Areas with Particular Emphasis on Forest Proximity. Diversity. 2022; 14(12):1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121141

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutniczak, Agnieszka, Alina Urbisz, Andrzej Urbisz, and Łukasz Strzeleczek. 2022. "Factors Affecting Plant Composition in Abandoned Railway Areas with Particular Emphasis on Forest Proximity" Diversity 14, no. 12: 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121141

APA StyleHutniczak, A., Urbisz, A., Urbisz, A., & Strzeleczek, Ł. (2022). Factors Affecting Plant Composition in Abandoned Railway Areas with Particular Emphasis on Forest Proximity. Diversity, 14(12), 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121141