Johnston Atoll: Reef Fish Hybrid Zone between Hawaii and the Equatorial Pacific

Abstract

1. Introduction

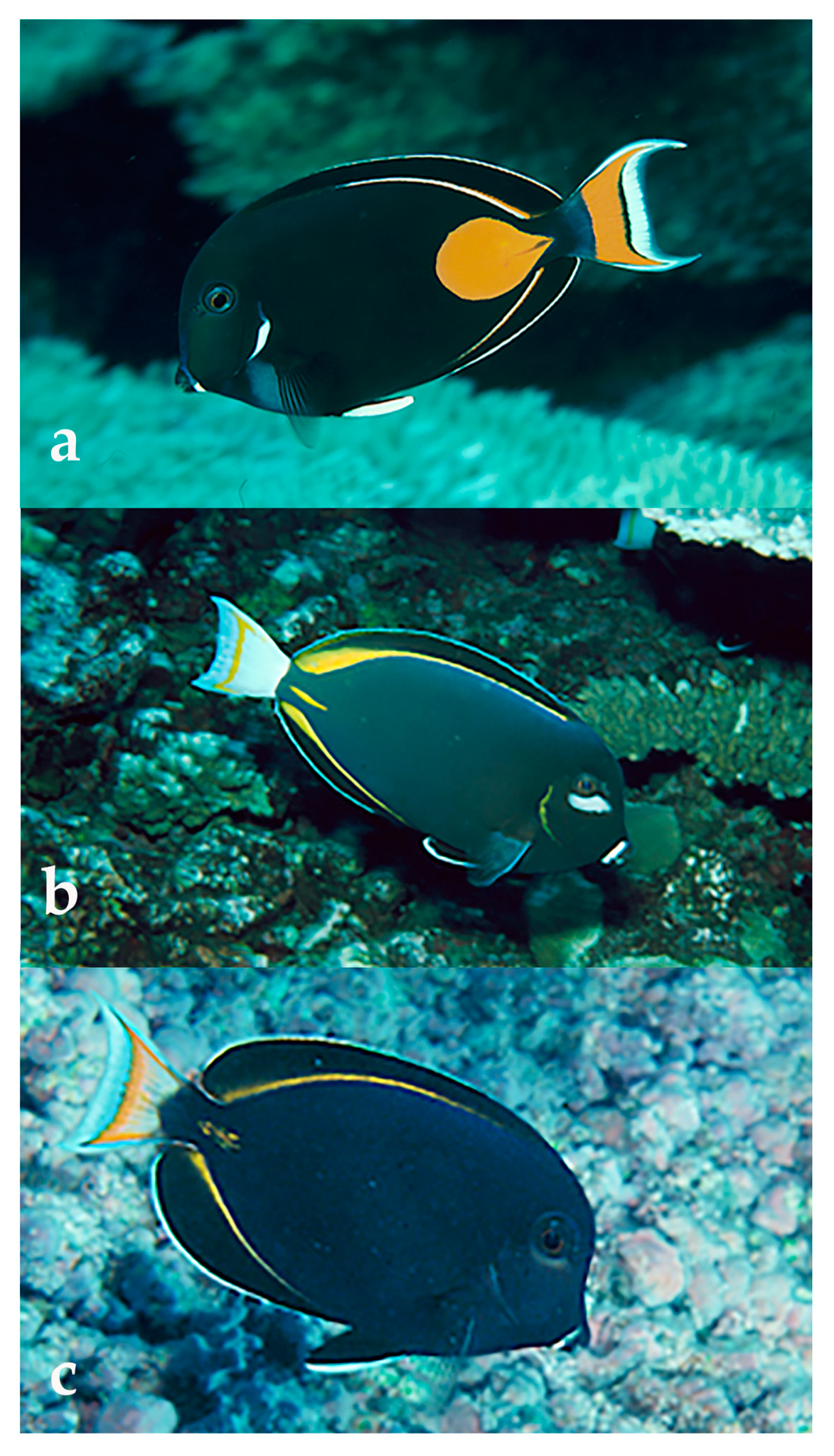

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location

2.2. Underwater Surveys

3. Results

3.1. Hybrid Thalassoma Species

3.2. Hybrid Abudefduf Species

3.3. Hybrid Acanthurus Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hubbs, C.L. Hybridization between fish species in nature. Zoolog. Syst. 1955, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yaakub, S.M.; Bellwood, D.R.; van Herwerden, L.; Walsh, F.M. Hybridization in coral reef fishes: Introgression and bi-directional gene exchange in Thalassoma (family Labridae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006, 40, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanari, S.R.; van Herwerden, L.; Pratchett, M.S.; Hobbs, J.P.A.; Fugedi, A. Reef fish hybridization: Lessons learnt from butterflyfishes (genus Chaetodon). Ecol. Evol. 2012, 2, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanari, S.R.; Hobbs, J.P.A.; Pratchett, M.S.; van Herwerden, L. The importance of ecological and behavioural data in studies of hybridization among marine fishes. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 2016, 26, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.F.; Konings, A.; Kornfield, I. Hybrid origin of a cichlid population in Lake Malawi: Implications for genetic variation and species diversity. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 2497–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitelli, F.; Hyndes, G.A.; Saunders, B.J.; Blake, D.; Newman, S.J.; Hobbs, J.A. Do ecological traits of low abundance and niche overlap promote hybridisation among coral-reef angelfishes. Coral Reefs 2019, 38, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.A.; Salmond, J.K. Cohabitation of Indian and Pacific Ocean species at Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Coral Reefs 2008, 27, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBattista, J.D.; Wilcox, C.; Craig, M.T.; Rocha, L.A.; Bowen, B.W. Phylogeography of the Pacific blueline surgeonfish, Acanthurus nigroris, reveals high genetic connectivity and a cryptic endemic species in the Hawaiian Archipelago. J. Mar. Biol 2011, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, J.E.; Lobel, P.S.; Chave, E.H. Annotated checklist of the fishes of Johnston Island. Pac. Sci. 1985, 39, 24–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki, R.K. Centropyge nahackyi, a new species of angelfish from Johnston Atoll (Teleostei: Pomacanthidae). Copeia 1989, 4, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, P.S. Marine life of Johnston Atoll, Central Pacific Ocean; Natural World Press: Vida, OR, USA, 2003; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, D.; Kosaki, R.; Spalding, H.; Whitton, R.; Pyle, R.; Sherwood, A.; Tsuda, R.; Calcinai, B. Mesophotic surveys of the flora and fauna at Johnston Atoll, Central Pacific Ocean. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 2014, 7, E68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragos, J.E.; Jokiel, P.L. Reef corals of Johnston Atoll: One of the world’s most isolated reefs. Coral Reefs 1986, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaki, R.K.; Pyle, R.L.; Randall, J.E.; Irons, D.K. New records of fishes from Johnston Atoll with notes on biogeography. Pac. Sci. 1991, 45, 186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gosline, W.A. The inshore fish fauna of Johnston Island, a central Pacific atoll. Pac. Sci. 1955, 9, 442–480. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, D.R. Colonization of the Hawaiian Archipelago via Johnston Atoll: A characterization of oceanographic transport corridors for pelagic larvae using computer simulation. Coral Reefs 2006, 25, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessios, H.A.; Robertson, D.R. Crossing the impassable: Genetic connections in 20 reef fishes across the eastern Pacific barrier. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006, 273, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, G.; Bucciarelli, G.; Costagliola, D.; Robertson, D.R. Evolution of coral reef fish Thalassoma spp. (Labridae). 1. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography. Mar. Biol. 2004, 144, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irons, D.; Kosaki, R.; Parrish, J. Johnston Atoll resource survey Final Report, phase six (21 Jul 89–20 Jul 90); Army Corps Engineers: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1990; 147. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel, P.S.; Lobel, L.K. Aspects of the biology and geology of Johnston and Wake Atolls, Pacific Ocean. In Coral Reefs of the USA; Series: Coral Reefs of the World; Riegl, B., Dodge, R.E., Eds.; Springer Verlag Press: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 655–689. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel, L.K.; Lobel, P.S. Current status of the US military atolls in the Pacific: Johnston and Wake. In World Seas: An. Environmental Evaluation; Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic Press Cambridge: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 645–659. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, R.L.; Randall, J.E. A review of hybridization in marine angelfishes (Perciformes: Pomacanthidae). Env. Biol. Fish. 1994, 41, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, J.E.; Frische, J. Hybrid surgeonfishes of the Acanthurus achilles complex. Aqua. 2000, 4, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, K.; James, S.A.; Randall, J.E.; Suzumoto, A.Y. Two hybrids of carangid fishes of the genus Caranx, C. ignobilis x C. melampygus and C. melampygus x C. sexfasciatus, from the Hawaiian Islands. Zool. Stud. 2007, 46, 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, J.E.; Justine, J. Cephalopholis aurantia × C. spiloparaea, a hybrid serranid fish from New Caledonia. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2008, 56, 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- Marie, A.D.; van Herwerden, L.; Choat, J.H.; Hobbs, J.-P.A. Hybridization of reef fishes at the Indo-Pacific biogeographic barrier: A case study. Coral Reefs 2007, 26, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K.E.; Barber, P.H.; Crandall, E.D.; Ablan-Lagman, C.A.; Ambariyanto; Ngurah Mahardika, G.; MabelManjaji-Matsumoto, B.; Juinio-Meñez, M.A.; Santos, M.D.; Starger, C.J.; et al. Comparative phylogeography of the Coral Triangle and implications for marine management. J. Mar. Biol 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBattista, J.D.; Rocha, L.A.; Hobbs, J.P.A.; He, S.; Priest, M.A.; Sinclair-Taylor, T.H.; Bowen, B.W.; Berumen, M.L. When biogeographical provinces collide: Hybridization of reef fishes at the crossroads of marine biogeographical provinces in the Arabian Sea. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivivasa Rao, K.; Lakshmi, K. Cryptic hybridization in marine fishes: Significance of narrow hybrid zones in identifying stable hybrid populations. J. Nat. Hist. 1999, 33, 1237–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.L. Menephorus Poey, a serranid genus based on two hybrids of Cephalopholis fulva and Paranthias furcifer, with comments on the systematic placement of Paranthias. Am. Mus. Novit. 1966, 2276, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, J.E.; Miroz, A. Thalassoma lunare x Thalassoma rueppellii, a hybrid labrid fish from the Red Sea. Aqua. 2001, 4, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F.M.; Randall, J.E. Thalassoma jansenii x T. quinquevittatum and T. nigrofasciatum x T. quinquevittatum, hybrid labrid fishes from Indonesia and the Coral Sea. Aqua. 2004, 2, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Costagliola, D.; Robertson, D.R.; Guidetti, P.; Stefanni, S.; Wirtz, P.; Heiser, J.B.; Bernardi, G. Evolution of coral reef fish Thalassoma spp. (Labridae). 2. Evolution of the eastern Atlantic species. Mar. Biol. 2004, 144, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruska, K.P.; Peyton, K.A. Interspecific spawning between a recent immigrant and an endemic damselfish (Pisces: Pomacentridae) in the Hawaiian Islands. Pac. Sci. 2007, 61, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coleman, R.R.; Gaither, M.R.; Kimokeo, B.; Stanton, F.G.; Bowen, B.W.; Toonen, R.J. Large-scale introduction of the Indo-Pacific damselfish Abudefduf vaigiensis into Hawai‘i promotes genetic swamping of the endemic congener A. abdominalis. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 5552–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabbar, A.; Yu, B. The 1998–2000 La Niña in the context of historically strong La Niña events. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, D13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, R.M.; Magnuson, J.J. Ecological significance of a drifting object to pelagic fishes. Pac. Sci. 1967, 21, 486–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, P.A. Marine fish assemblages associated with fish aggregating devices (FADs): Effects of fish removal, FAD size, fouling communities, and prior recruits. Fish. Bull. 2003, 101, 835–850. [Google Scholar]

- Osca, D.; Tanduo, V.; Tiralongo, F.; Giovos, I.; Almabruk, S.A.A.; Crocetta, F.; Rizgalla, J. The Indo-Pacific Sergeant Abudefduf vaigiensis (Quoy & Gaimard, 1825) (Perciformes: Pomacentridae) in Libya, South-Central Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, J.A.M.; Borsa, P.; Chen, W. Phylogeography of the sergeants Abudefduf sexfasciatus and A. vaigiensis reveals complex introgression patterns between two widespread and sympatric Indo-West Pacific reef fishes. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 2527–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobel, P.S. Comparative settlement age of damselfish larvae (Plectroglyphidodon imparipennis, Pomacentridae) from Hawaii and Johnston Atoll. Biol. Bull. 1997, 193, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenggardjaja, K.A.; Bowen, B.W.; Bernardi, G. Reef fish dispersal in the Hawaiian Archipelago: Comparative phylogeography of three endemic damselfishes. J. Mar. Biol. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon, M.L.; Nelson, P.A.; De Martini, E.; Walsh, W.J.; Bernardi, G. Phylogeography, historical demography, and the role of post-settlement ecology in two Hawaiian damselfish species. Mar. Biol. 2008, 153, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenggardjaja, K.A.; Bowen, B.W.; Bernardi, G. Vertical and horizontal genetic connectivity in Chromis verater, an endemic damselfish found on shallow and mesophotic reefs in the Hawaiian Archipelago and adjacent Johnston Atoll. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skillings, D.J.; Bird, C.E.; Toonen, R.J. Gateways to Hawai’i: Genetic population structure of the tropical sea cucumber Holothuria atra. J. Mar. Biol. 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, J.E. Reef and shore fishes of the Hawaiian Islands; University of Hawaii, Honolulu Sea Grant Program: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2007; p. 546. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, B.C. Duration of the planktonic larval stage of one hundred species of Pacific and Atlantic wrasses (family Labridae). Mar. Biol. 1986, 90, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Location | Depth (m) | T. Duppery | T. Lutescens | Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 Dec 91 | HO Site | 1–7 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 10 May 92 | North Is. Channel | 3–7 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 Jun 95 | Sand Is. Wharf | 1–7 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 12 Sep 97 | Outside Munsen’s Gap | 4–10 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 Sep 97 | West Camera Stand | 5–7 | 18 | 2 | 4 1 |

| 13 Sep 97 | Outside Munsen’s Gap | 5–10 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Total number | 38 | 8 | 20 | ||

| % Total | 58 | 12 | 30 |

| Date | Location | # Fish Observed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Abdominalis | A. Vaigiensis | ||

| 15 Dec 91 | HO Site | 2 | 0 |

| 5 Jun 95 | Munsen’s Gap | 1 | 0 |

| 20 Feb 99 | Navy Pier | 1 | 0 |

| 19 Apr 99 | Munsen’s Gap | 0 | 1 |

| 3 Jun 99 | Navy Pier | 1 | 0 |

| 3 Jun 99 | Donovan’s Reef | 0 | 2 |

| 28 Aug 99 | Buoy 6 | 0 | 121 |

| 28 Aug 99 | Buoy 14 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 Aug 99 | North Is. Back Reef | 7-10 | 502 |

| 18 Aug 00 | North Is. Back Reef | 10 | 503 |

| 13 Mar 01 | Buoy 14 | 0 | 3 |

| 17 Apr 01 | Buoy 13 | 0 | 2 |

| 13 May 01 | North Island | 3 | 0 |

| 23 Jan 03 | Tugboat | 0 | 1 |

| 20 Feb 03 | Tugboat | 0 | 1 |

| 24 Feb 03 | Boat Ramp | 0 | 2 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lobel, P.S.; Lobel, L.K.; Randall, J.E. Johnston Atoll: Reef Fish Hybrid Zone between Hawaii and the Equatorial Pacific. Diversity 2020, 12, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12020083

Lobel PS, Lobel LK, Randall JE. Johnston Atoll: Reef Fish Hybrid Zone between Hawaii and the Equatorial Pacific. Diversity. 2020; 12(2):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12020083

Chicago/Turabian StyleLobel, Phillip S., Lisa K. Lobel, and John E. Randall. 2020. "Johnston Atoll: Reef Fish Hybrid Zone between Hawaii and the Equatorial Pacific" Diversity 12, no. 2: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12020083

APA StyleLobel, P. S., Lobel, L. K., & Randall, J. E. (2020). Johnston Atoll: Reef Fish Hybrid Zone between Hawaii and the Equatorial Pacific. Diversity, 12(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12020083