Do Dominant Ants Affect Secondary Productivity, Behavior and Diversity in a Guild of Woodland Ants?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Sampling

2.2.1. Community and Population-Level Effects

2.2.2. Individual-Level Effects

2.2.3. Worker-Level Effects

2.3. Estimating Dominance

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Is the Pooled Abundance of Non-Dominant Species Negatively Related to the Abundance of the Dominant Species?

2.4.2. Is the Colony Size and/or Productivity of Non-Dominant Ant Species Negatively Influenced by Proximity to a F. subsericea Colony?

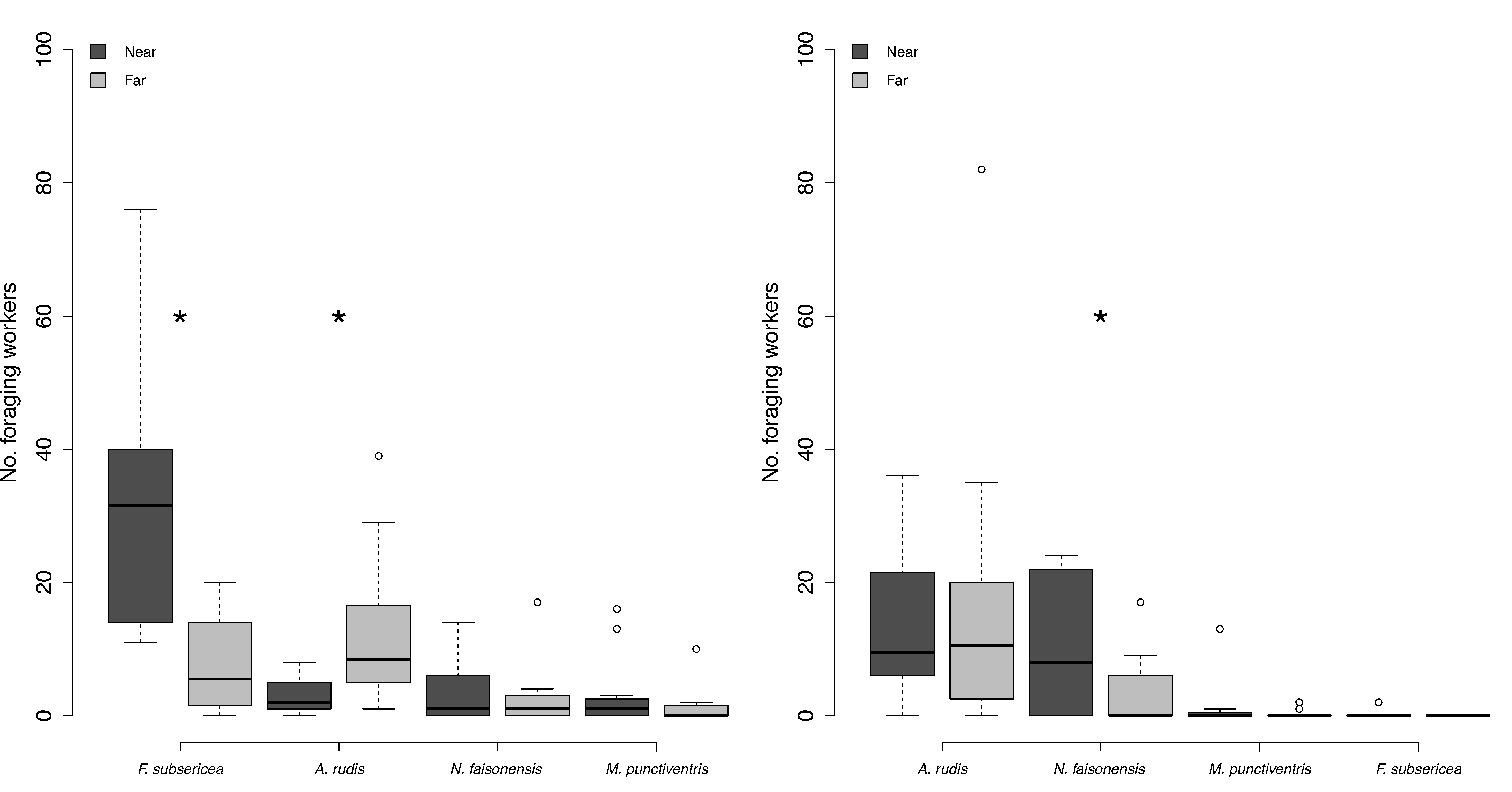

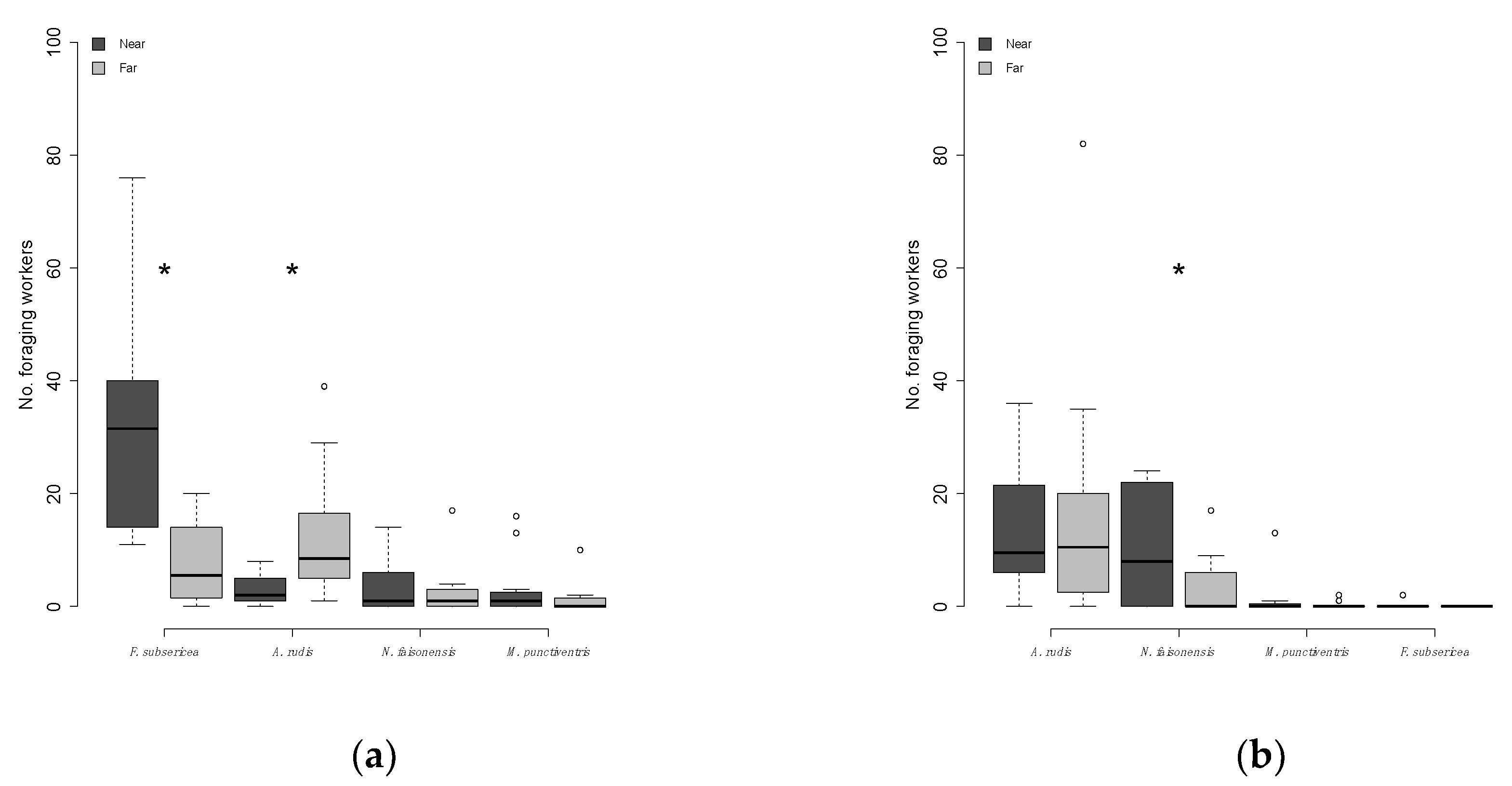

2.4.3. Is Resource Use by Non-Dominant Ants Negatively Influenced by Proximity to a F. subsericea Colony?

2.4.4. Are Temporal Patterns of Foraging Activity in Non-Dominant Species Are Negatively Related to Those of F. subsericea?

3. Results

3.1. Species Richness and Dominance

3.2. Is the Pooled Abundance of Non-Dominant Species Negatively Related to the Abundance of the Dominant Species?

3.3. Is Colony Size and/or Productivity of Non-Dominant Ant Species Negatively Influenced by Proximity to a Dominant Ant Colony?

3.4. Is Resource Exploitation by Non-Dominant Ants Negatively Influenced by Proximity to a Dominant Ant Colony?

3.5. Are Temporal Patterns of Foraging Activity in Non-dominant Species Negatively Related to Those of the Dominant Species?

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grime, J.P. Colonization, Succession and Stability; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen, D.H. Herbivores and the Number of Tree Species in Tropical Forests. Am. Nat. 1970, 104, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. On the role of natural enemies in preventing competitive exclusion in some marine animals and in rain forest trees. In Dynamics of Population; Den Boer, P.J., Gradwell, G.R., Eds.; Pudoc: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, C.L. Dominant ants can control assemblage species richness in a South African savanna. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, C.L.; Sinclair, B.J.; Andersen, A.N.; Gaston, K.J.; Chown, S.L. Constraint and competition in assemblages: A cross-continental and modeling approach for ants. Am. Nat. 2005, 165, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Arnett, A.E. Biogeographic effects of red fire ant invasion. Ecol. Lett. 2000, 3, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holway, D.A. Effect of Argentina ant invasions on ground-dwelling arthropods in northern California riparian woodlands. Oecologia 1998, 116, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human, K.G.; Gordon, D.M. Exploitation and interference competition between the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile, and native ant species. Oecologia 1996, 105, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, S.; Savignano, D. Invasion of Polygyne Fire Ants Decimates Native Ants and Disrupts Arthropod Community. Ecology 1990, 71, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, N.J.; Gotelli, N.J.; Heller, N.E.; Gordon, D.M. Community disassembly by an invasive species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2474–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.-P.; Fordyce, J.A.; Gotelli, N.J.; Sanders, N.J. Invasive ants alter the phylogenetic structure of ant communities. Ecology 2009, 90, 2664–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, N.J.; Crutsinger, G.M.; Dunn, R.R.; Majer, J.D.; Delabie, J.H.C. An ant mosaic revisited: Dominant ant species disassemble arboreal ant communities but co-occur randomly. Biotropica 2007, 39, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.W.; Lessard, J.P.; Bernau, C.R.; Cook, S.C. The tropical ant mosaic in a primary Bornean rain forest. Biotropica 2007, 39, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.A. Ant Distribution Patterns in a Cameroonian Cocoa Plantation—Investigation of the Ant Mosaic Hypothesis. Oecologia 1984, 62, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leston, D. Neotropical Ant Mosaic. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1978, 71, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J.D.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Smith, M.R.B. Arboreal Ant Community Patterns in Brazilian Cocoa Farms. Biotropica 1994, 26, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.S. Territory Defense by the Ant Azteca-Trigona—Maintenance of an Arboreal Ant Mosaic. Oecologia 1994, 97, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N. Regulation of Momentary Diversity by Dominant Species in Exceptionally Rich Ant Communities of the Australian Seasonal Tropics. Am. Nat. 1992, 140, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, J.K.; Nelson, A.S.; Berggreen, J.D.; Boulay, R.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Testing trade-offs and the dominance–impoverishment rule among ant communities. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnan, X.; Andersen, A.N.; Gibb, H.; Parr, C.L.; Sanders, N.J.; Dunn, R.R.; Angulo, E.; Baccaro, F.B.; Bishop, T.R.; Boulay, R.; et al. Dominance–diversity relationships in ant communities differ with invasion. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 4614–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, H. Dominant meat ants affect only their specialist predator in an epigaeic arthropod community. Oecologia 2003, 136, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, H.; Hochuli, D.F. Removal experiment reveals limited effects of a behaviorally dominant species on ant assemblages. Ecology 2004, 85, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, H.; Johansson, T. Field tests of interspecific competition in ant assemblages: Revisiting the dominant red wood ants. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011, 80, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslippe, R.J.; Savolainen, R. Mechanisms of Competition in a Guild of Formicine Ants. Oikos 1995, 72, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbers, J.M.; Banschbach, V.S. Food supply and reproductive allocation in forest ants: Repeated experiments give different results. Oikos 1998, 83, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, R. Colony Success of the Submissive Ant Formica-Fusca within Territories of the Dominant Formica-Polyctena. Ecol. Entomol. 1990, 15, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, R. Interference by Wood Ant Influences Size Selection and Retrieval Rate of Prey by Formica-Fusca. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1991, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepsalainen, K.; Savolainen, R. The Effect of Interference by Formicine Ants on the Foraging of Myrmica. J. Anim. Ecol. 1990, 59, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellers, J.H. Interference and Exploitation in a Guild of Woodland Ants. Ecology 1987, 68, 1466–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbers, J.M. Community Structure in North Temperate Ants—Temporal and Spatial Variation. Oecologia 1989, 81, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, R.; Vepsalainen, K. A Competition Hierarchy among Boreal Ants—Impact on Resource Partitioning and Community Structure. Oikos 1988, 51, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, R.; Vepsalainen, K. Niche Differentiation of Ant Species within Territories of the Wood Ant Formica Polyctena. Oikos 1989, 56, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, R.; Vepsalainen, K.; Wuorenrinne, H. Ant Assemblages in the Taiga Biome—Testing the Role of Territorial Wood Ants. Oecologia 1989, 81, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D. The Importance of the Mechanisms of Interspecific Competition. Am. Nat. 1987, 129, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, X.; Retana, J.; Manzaneda, A. The role of competition by dominants and temperature in the foraging of subordinate species in Mediterranean ant communities. Oecologia 1998, 117, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holway, D.A. Competitive mechanisms underlying the displacement of native ants by the invasive Argentine ant. Ecology 1999, 80, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erős, K.; Maák, I.; Markó, B.; Babik, H.; Ślipiński, P.; Nicoară, R.; Czechowski, W. Competitive pressure by territorials promotes the utilization of unusual food source by subordinate ants in temperate European woodlands. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 32, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.J.; Parr, C. Numerically dominant species drive patterns in resource use along a vertical gradient in tropical ant assemblages. Biotropica 2020, 52, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N. Not enough niches: Non-equilibrial processes promoting species coexistence in diverse ant communities. Austral. Ecol. 2008, 33, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francoeur, A. Révision taxonomique des espèces néarctiques du groupe fusca, genre Formica (Formicidae, Hymenoptera). Mem. Soc. Ent. Québec 1973, 3, 1–316. [Google Scholar]

- Fellers, J.H. Daily and Seasonal Activity in Woodland Ants. Oecologia 1989, 78, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.-P.; Dunn, R.R.; Parker, C.R.; Sanders, N.J. Rarity and Diversity in Forest Ant Assemblages of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Southeast. Nat. 2007, 6, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.-P.; Sackett, T.E.; Reynolds, W.N.; Fowler, D.A.; Sanders, N.J. Determinants of the detrital arthropod community structure: The effects of temperature and resources along an environmental gradient. Oikos 2011, 120, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, N.J.; Lessard, J.-P.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Dunn, R.R. Temperature, but not productivity or geometry, predicts elevational diversity gradients in ants across spatial grains. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007, 16, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammell, M.E.; Way, M.J.; Paiva, M.R. Diversity and structure of ant communities associated with oak, pine, eucalyptus and arable habitats in Portugal. Insectes Sociaux 1996, 43, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuble, K.; Kirkman, L.K.; Carroll, C.R. Patterns of abundance of fire ants and native ants in a native ecosystem. Ecol. Entomol. 2009, 34, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBrun, E.; Feener, D. When trade-offs interact: Balance of terror enforces dominance discovery trade-off in a local ant assemblage. J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A.M.; Record, S.; Arguello, A.; Gotelli, N.J. Rapid inventory of the ant assemblage in a temperate hardwood forest: Species composition and assessment of sampling methods. Environ. Entomol. 2007, 36, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longino, J.T.; Colwell, R.K. Biodiversity assessment using structured inventory: Capturing the ant fauna of a tropical rain forest. Ecol. Appl. 1997, 7, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.R. Size–abundance relationships in Florida ant communities reveal how ants break the energetic equivalence rule. Ecol. Entomol. 2010, 35, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Ellison, A.M. Biogeography at a regional scale: Determinants of ant species density in new england bogs and forests. Ecology 2002, 83, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubertazzi, D. The Biology and Natural History of Aphaenogaster rudis. Psyche 2012, 2012, 752815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhn, T.P.; Wright, C.G.; Farrier, M.H. Notes on the biology of the ant Paratrechina faisonensis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 1992, 108, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspari, M. Testing resource-based models of patchiness in four Neotropical litter ant assemblages. Oikos 1996, 76, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, T.P.; Hoover, J.R.; Jasper, G.S.; Kelly, M.S.; Polis, A.M.; Spangler, C.M.; Watson, B.J. Resource heterogeneity affects demography of the Costa Rican ant Aphaenogaster araneoides. J. Trop. Ecol. 2002, 18, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugnon, G.; Fourcassie, V. How Do Red Wood Ants Orient during Diurnal and Nocturnal Foraging in a 3 Dimensional System. 2. Field Experiments. Insectes Sociaux 1988, 35, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillery, A.E.; Fell, R.D. Chemistry and Behavioral significance of rectal and accessory gland contents in Camponotus pennsylvanicus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2000, 93, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.A.; Snelling, R.R.; Jones, T.H. Distribution, ecology and behavior of Anochetus kempfi (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and description of the sexual forms. Sociobiology 2000, 36, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Retana, J.; Cerdá, X. Patterns of diversity and composition of Mediterranean ground ant communities tracking spatial and temporal variability in the thermal environment. Oecologia 2000, 123, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuble, K.L.; Jurić, I.; Cerdá, X.; Sanders, N.J. Dominance hierarchies are a dominant paradigm in ant ecology (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), but should they be? And what is a dominance hierarchy anyways? Myrmecol. News 2017, 24, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.P.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Temperature-mediated coexistence in forest ant communities. Insectes Sociaux 2009, 56, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschinkel, W.R.; Hess, C.A. Arboreal ant community of a pine forest in northern Florida. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1999, 92, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepsalainen, K.; Pisarski, B. Assembly of Island Ant Communities. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 1982, 19, 327–335. [Google Scholar]

- Colley, W.N. Colley’s Bias Free College Football Ranking Method: The Colley Matrix Explained. Available online: http://www.colleyrankings.com/matrate.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2009).

- Longino, J.T.; Coddington, J.; Colwell, R.K. The ant fauna of a tropical rain forest: Estimating species richness three different ways. Ecology 2002, 83, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspari, M.; Weiser, M.D. The size–grain hypothesis and interspecific scaling in ants. Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, M.J.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Body size, colony size, and range size in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Are patterns along elevational and latitudinal gradients consistent with Bergmann’s Rule? Myrmecol. News 2007, 10, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Ellison, A.M. A Primer of Ecological Statistics; Sinauer Associates, INC.: Sunderlan, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chesson, P. Mechanisms of Maintenance of Species Diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, P. Updates on mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 1773–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E. The Ants; Belknap: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, D.W. Some Consequences of Diffuse Competition in a Desert Ant Community. Am. Nat. 1980, 116, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.W. An Experimental Study of Diffuse Competition in Harvester Ants. Am. Nat. 1985, 125, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne, R.L. A Latitudinal Gradient in Rates of Ant Predation. Ecology 1979, 60, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D.; Lessard, J.-P.; Sanders, N.J. Niche filtering rather than partitioning shapes the structure of temperate forest ant communities. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.-P.; Borregaard, M.K.; Fordyce, J.A.; Rahbek, C.; Weiser, M.D.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Strong influence of regional species pools on continent-wide structuring of local communities. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuble, K.L.; Rodriguez-Cabal, M.A.; McCormick, G.L.; Jurić, I.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Tradeoffs, competition, and coexistence in eastern deciduous forest ant communities. Oecologia 2013, 171, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, M.; Gotelli, N.J. Spatial and temporal niche partitioning in grassland ants. Oecologia 2001, 126, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.R.; Parker, C.R.; Sanders, N.J. Temporal patterns of diversity: Assessing the biotic and abiotic controls on ant assemblages. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2007, 91, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, X.; Arnan, X.; Retana, J. Is competition a significant hallmark of ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) ecology? Myrmecol. News 2013, 18, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- LeBrun, E.G.; Tillberg, C.V.; Suarez, A.V.; Folgarait, P.J.; Smith, C.R.; Holway, D.A. An experimental study of competition between Fire Ants and Argentine Ants in their native range. Ecology 2007, 88, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuble, K.L.; Kirkman, L.K.; Carroll, C.R.; Sanders, N.J. Relative effects of disturbance on Red Imported Fire Ants and native ant apecies in a longleaf pine ecosystem. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, S.B.; Fisher, R.N.; Jetz, W.; Holway, D.A. Biotic and abiotic controls of Argentine Ant invasion success at local and landscape scales. Ecology 2007, 88, 3164–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Worker Count | Abundance | Worker Body Size | Predicted Worker Mass | Colony Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Workers | No. of Incidence | Weber’s Length (mm) | (g) | No. of Workers | |

| Aphaenogaster fulva Roger | 10 | 3 | 1.48 | 1.64 | 281 |

| Aphaenogaster rudis Enzmann | 712 | 123 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 303 |

| Camponotus americanus Mayr | 3 | 3 | 2.59 | 9.74 | 3560 |

| Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer) | 20 | 18 | 2.52 | 8.93 | 2222 |

| Formica subsericea Say | 181 | 57 | 2.33 | 6.96 | 8919 |

| Lasius alienus (Förster) | 87 | 19 | 1.42 | 1.44 | 3000 |

| Myrmica punctiventris Roger | 107 | 36 | 1.53 | 1.83 | 86 |

| Nylanderia faisonensis (Forel) | 25 | 18 | 0.61 | 0.10 | 268 |

| Prenolepis imparis (Say) | 8 | 3 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 3370 |

| Temnothorax longispinosus (Roger) | 5 | 4 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 47 |

| Species | Behavioral Dominance | Numerical Dominance | Total Predicted Biomass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colley Ranking | No. of Pitfall Traps | No. Pitfall Traps × Colony Size × Worker Biomass | |

| Aphaenogaster fulva Roger | 0.71 (2) | 3 (8) | 1.39 (8) |

| Aphaenogaster rudis Enzmann | 0.40 (7) | 123 (1) | 52.55 (5) |

| Camponotus americanus Mayr | 0.68 (4) | 3 (9) | 104. 06 (3) |

| Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer) | 0.93 (1) | 18 (5) | 357.19 (2) |

| Formica subsericea Say | 0.70 (3) | 57 (2) | 3538.74 (1) |

| Lasius alienus (Förster) | 0.68 (5) | 19 (4) | 82.19 (4) |

| Myrmica punctiventris Roger | 0.40 (8) | 36 (3) | 5.66(6) |

| Nylanderia faisonensis (Forel) | 0.08 (10) | 18 (6) | 0.47 (9) |

| Prenolepis imparis (Say) | 0.58 (6) | 3 (10) | 3.54 (7) |

| Temnothorax longispinosus (Roger) | 0.20 (9) | 4 (7) | 0.02 (10) |

| Response Variable | Taxa | Test | n | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony size | A. rudis | Wilcoxon Rank Sums | 10 | Z = 0.12 | 0.91 |

| Colony size | N. faisonensis | Two-sample t-test | 11.53 | t-Ratio = −0.21 | 0.42 |

| Colony productivity | A. rudis | Wilcoxon Rank Sums | 10 | Z = −0.46 | 0.64 |

| Colony productivity | N. faisonensis | Wilcoxon Rank Sums | 11.61 | Z = −1.74 | 0.08 |

| Source of Variation | Response Variable | Taxa | Test | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (day) | Species richness | all | Paired t-test | t-Ratio = −1.20 | 0.13 |

| Distance (day) | Worker abundance | all | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = 23.00 | 0.04 * |

| Distance (day) | Worker abundance | Ar | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = 27.50 | 0.01 * |

| Distance (day) | Worker abundance | Fs | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = −39.00 | <0.0001 ** |

| Distance (day) | Worker abundance | M | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = −9.00 | 0.13 |

| Distance (day) | Worker abundance | Nf | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = −2.00 | 0.41 |

| Distance (night) | Species richness | all | Paired t-test | t-Ratio = 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Distance (night) | Worker abundance | all | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = −2.00 | 0.46 |

| Distance (night) | Worker abundance | Ar | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = −2.00 | 0.55 |

| Distance (night) | Worker abundance | Fs | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | NA | NA |

| Distance (night) | Worker abundance | M | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank | Z = −1.50 | 0.41 |

| Distance (night) | Worker abundance | Nf | Paired t-test | t-Ratio = −2.36 | 0.02 * |

| Response Variable | Taxa | Test | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species richness | all | t-test | t = 3.75 | 0.002 ** |

| Worker abundance | all | t-test | t = −2.94 | 0.007 ** |

| Worker abundance | Ar | t-test | t = −2.56 | 0.01 * |

| Worker abundance | Fs | t-test | t = 5.57 | <0.0001 ** |

| Worker abundance | M | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank | Z = 22.5 | 0.002 ** |

| Worker abundance | Nf | t-test | t = −2.58 | 0.01 * |

| Species | Day | Night | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Aphaenogaster rudis Enzmann | 7.67 | 1.95 | 15.13 | 3.6 |

| Camponotus americanus Mayr | 1 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.5 |

| Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer) | 0.38 | 0.25 | 1.38 | 0.76 |

| Formica subsericea Say | 20.25 | 3.97 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Lasius alienus (Förster) | 2.29 | 2.25 | 2.33 | 2.16 |

| Myrmica punctiventris Roger | 2.21 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.54 |

| Nylanderia faisonensis (Forel) | 3.08 | 0.97 | 7.33 | 1.88 |

| Prenolepis imparis (Say) | 0 | 0 | 4.25 | 4.25 |

| Temnothorax curvispinosus (Mayr) | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 |

| Temnothorax longispinosus (Roger) | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lessard, J.-P.; Stuble, K.L.; Sanders, N.J. Do Dominant Ants Affect Secondary Productivity, Behavior and Diversity in a Guild of Woodland Ants? Diversity 2020, 12, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12120460

Lessard J-P, Stuble KL, Sanders NJ. Do Dominant Ants Affect Secondary Productivity, Behavior and Diversity in a Guild of Woodland Ants? Diversity. 2020; 12(12):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12120460

Chicago/Turabian StyleLessard, Jean-Philippe, Katharine L. Stuble, and Nathan J. Sanders. 2020. "Do Dominant Ants Affect Secondary Productivity, Behavior and Diversity in a Guild of Woodland Ants?" Diversity 12, no. 12: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12120460

APA StyleLessard, J.-P., Stuble, K. L., & Sanders, N. J. (2020). Do Dominant Ants Affect Secondary Productivity, Behavior and Diversity in a Guild of Woodland Ants? Diversity, 12(12), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12120460