Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

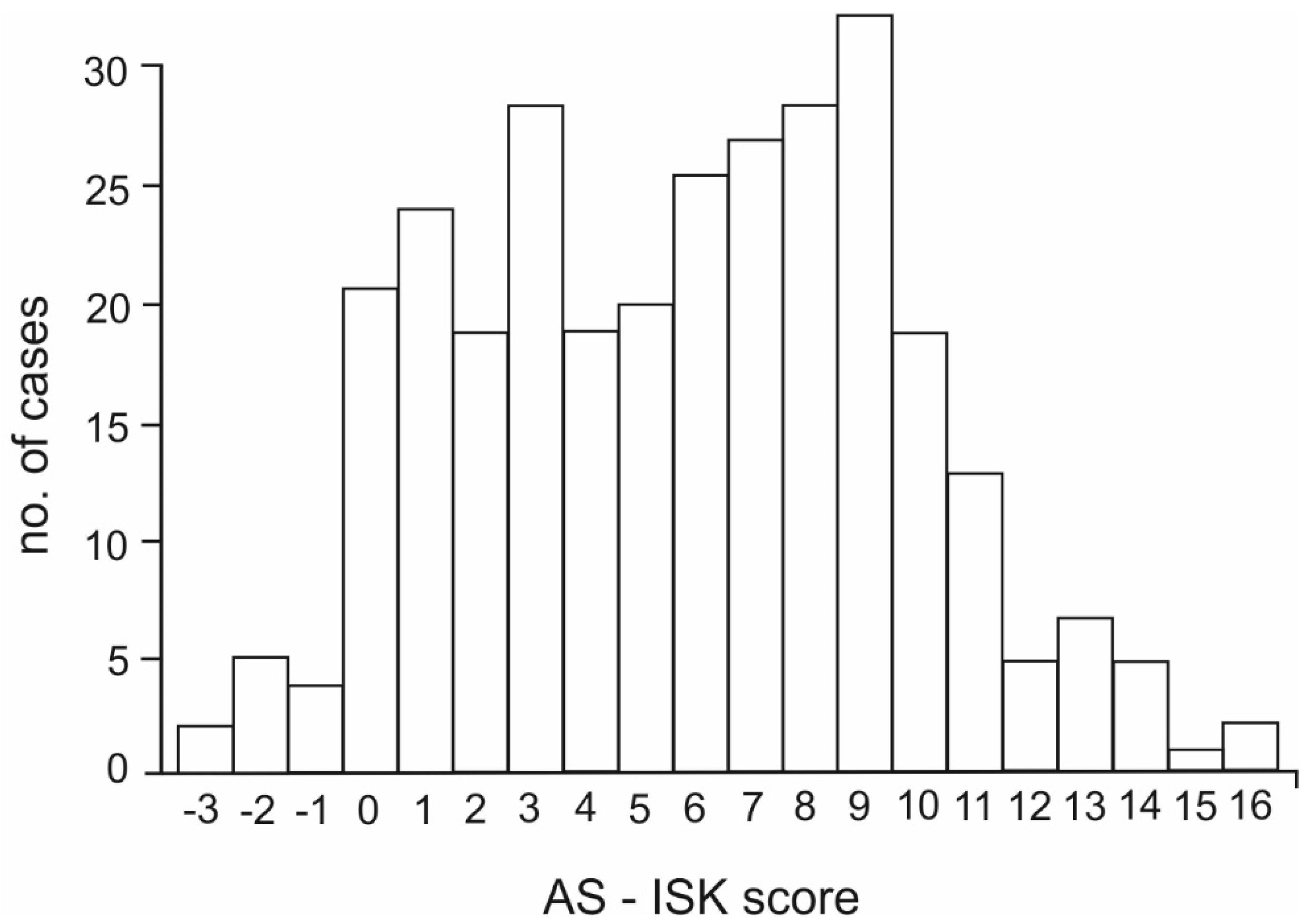

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Family | Species | Distribution Map Available/Presence of Climate Station | RAM | AS-ISK (Biology/Ecology Score Only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamaleonidae | Bradypodion setaroi | yes | 0.508 | 4 |

| Bradypodion thamnobates | yes | 0.508 | 5 | |

| Brookesia betschyi | yes | 0.508 | 3 | |

| Brookesia brygooi | yes | 0.508 | 4 | |

| Brookesia ebenaui | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia griveaudi | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia minima | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia nasus | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia peyrierasi | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia stumpffi | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia therezieni | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Brookesia thieli | yes | 0.508 | 1 | |

| Chamaeleo calyptratus | yes | 0.624 | 8 | |

| Chamaeleo dilepis | yes | 0.731 | 6 | |

| Chamaeleo senegalensis | yes | 0.544 | 3 | |

| Furcifer bifidus | yes | 0.450 | 3 | |

| Furcifer lateralis | yes | 0.450 | 10 | |

| Furcifer oustaleti | yes | 0.450 | 10 | |

| Furcifer pardalis | yes | 0.450 | 8 | |

| Furcifer verrucosus | yes | 0.450 | 10 | |

| Furcifer wilsii | yes | 0.450 | 2 | |

| Rhampholeon acuminatus | no | |||

| Rhampholeon boulengeri | yes | 0.520 | −1 | |

| Rhampholeon nchisiensis | no | |||

| Rhampholeon spectrum | yes | 0.508 | −3 | |

| Rhampholeon spinosus | yes | 0.508 | −3 | |

| Rhampholeon temporalis | yes | 0.508 | −2 | |

| Rhampholeon viridis | yes | 0.508 | 1 | |

| Rieppelon brevicaudatus | yes | 0.508 | 0 | |

| Rieppeleon kerstenii | yes | 0.529 | 1 | |

| Trioceros bitaeniatus | yes | 0.586 | 7 | |

| Trioceros cristatus | yes | 0.450 | 6 | |

| Trioceros deremensis | yes | 0.450 | 3 | |

| Trioceros ellioti | yes | 0.461 | 9 | |

| Trioceros fuelleborni | yes | 0.450 | 7 | |

| Trioceros hoehnelii | yes | 0.528 | 11 | |

| Trioceros jacksonii | yes | 0.542 | 11 | |

| Trioceros melleri | yes | 0.450 | 3 | |

| Trioceros montium | no | |||

| Trioceros pfefferi | no | |||

| Trioceros quadricornis | no | |||

| Trioceros rudis | yes | 0.456 | 8 | |

| Trioceros werneri | yes | 0.450 | 6 | |

| Kinyongia boehmei | yes | 0.450 | 5 | |

| Kinyongia matschiei | yes | 0.450 | 2 | |

| Kinyongia multituberculata | yes | 0.450 | 1 | |

| Kinyongia tavetana | yes | 0.450 | 1 | |

| Kinyongia tenuis | yes | 0.450 | 1 | |

| Kinyongia uthmoelleri | yes | 0.450 | 1 | |

| Calumma boettgeri | yes | 0.450 | 7 | |

| Calumma brevicorne | yes | 0.450 | 3 | |

| Calumma gastrotaenia | yes | 0.450 | 3 | |

| Calumma guillaumeti | no | |||

| Calumma malthe | yes | 0.450 | 2 | |

| Calumma marojezense | yes | 0.450 | 1 | |

| Calumma nasutum | yes | 0.450 | 4 | |

| Gekkonidae | Aeluroscalabotes felinus | yes | 0.453 | −2 |

| Blaesodactylus antongilensis | yes | 0.241 | 0 | |

| Blaesodactylus sakalava | yes | 0.241 | 0 | |

| Cnemaspis africana | no | |||

| Cnemaspis barbouri | no | |||

| Cnemaspis quattuorseriata | no | |||

| Coleonyx elegans | yes | 0.220 | 5 | |

| Coleonyx mitratus | yes | 0.218 | 3 | |

| Cyrtodactylus fumosus | no | |||

| Cyrtopodion scabrum | yes | 0.577 | 8 | |

| Elasmodactylus tetensis | yes | 0.241 | 1 | |

| Elasmodactylus tuberculosus | yes | 0.241 | 3 | |

| Eublepharis macularius | yes | 0.251 | 8 | |

| Geckolepis polylepis | yes | 0.241 | 5 | |

| Gehyra vorax | yes | 0.241 | 0 | |

| Gekko badenii | yes | 0.162 | 4 | |

| Gekko gecko | yes | 0.106 | 6 | |

| Gekko grossmanni | yes | 0.162 | 6 | |

| Gekko monarchus | no | |||

| Gekko ulikovskii | yes | 0.162 | 6 | |

| Gekko vittatus | yes | 0.162 | 6 | |

| Gonatodes albogularis | no | |||

| Goniurosaurus lichtenfelderi | no | |||

| Hemidactylus ansorgii | no | |||

| Hemidactylus brookii | no | |||

| Hemidactylus fasciatus | yes | 0.369 | 9 | |

| Hemidactylus frenatus | yes | 0.370 | 13 | |

| Hemidactylus imbricatus | yes | 0.388 | 11 | |

| Hemidactylus platyurus | no | |||

| Hemidactylus prashadi | yes | 0.369 | 10 | |

| Hemidactylus ruspolii | no | |||

| Hemidactylus squamulatus | no | |||

| Hemidactylus tanganicus | no | |||

| Hemitheconyx caudicinctus | yes | 0.106 | 2 | |

| Holodactylus africanus | no | |||

| Homopholis fasciata | yes | 0.502 | 2 | |

| Lepidodactylus lugubris | yes | 0.355 | 13 | |

| Lygodactylus capensis | no | |||

| Lygodactylus gutturalis | no | |||

| Lygodactylus kimhowelli | no | |||

| Lygodactylus klemmeri | yes | 0.162 | 8 | |

| Lygodactylus luteopicturatus | no | |||

| Lygodactylus miops | yes | 0.162 | 4 | |

| Lygodactylus scheffleri | no | |||

| Lygodactylus williamsi | yes | 0.127 | 1 | |

| Matoatoa brevipes | yes | 0.162 | 0 | |

| Pachydactylus bibroni | no | |||

| Pachydactylus rangei | no | |||

| Paroedura androyensis | yes | 0.453 | 7 | |

| Paroedura bastardi | yes | 0.453 | 5 | |

| Paroedura masobe | yes | 0.453 | 1 | |

| Paroedura picta | yes | 0.453 | 7 | |

| Phelsuma dubia | no | |||

| Phelsuma laticauda | yes | 0.453 | ||

| Phelsuma lineata | yes | 0.403 | 6 | |

| Phelsuma madagascariensis | yes | 0.403 | 5 | |

| Phelsuma quadriocellata | yes | 0.403 | 3 | |

| Ptychozoon kuhli | no | |||

| Ptyodactylus guttatus | no | |||

| Ptyodactylus hasselquistii | yes | 0.061 | 10 | |

| Ptyodactylus ragazzi | no | |||

| Rhacodactylus auriculatus | yes | 0.106 | 0 | |

| Rhacodactylus chahoua | yes | 0.106 | 3 | |

| Rhacodactylus ciliatus | yes | 0.106 | 1 | |

| Sphaerodactylus sputator | yes | 0.213 | 6 | |

| Stenodactylus petrii | yes | 0.496 | 1 | |

| Stenodactylus sthenodactylus | yes | 0.369 | 5 | |

| Tarentola annularis | yes | 0.327 | 9 | |

| Tarentola delalandii | yes | 0.047 | 1 | |

| Tarentola mauretanica | yes | 0.274 | 1 | |

| Teratoscincus roborowskii | yes | 0.213 | 1 | |

| Teratoscincus scincus | yes | 0.213 | 1 | |

| Tropiocolotes steudneri | no | |||

| Tropiocolotes tripolitanus | yes | 0.505 | 1 | |

| Underwoodisaurus milii | yes | 0.920 | 7 | |

| Ebenavia inunguis | yes | 0.241 | 3 | |

| Uroplatus ebenaui | yes | 0.241 | 6 | |

| Uroplatus guentheri | yes | 0.241 | 2 | |

| Uroplatus fimbriatus | yes | 0.241 | 5 | |

| Uroplatus henkeli | yes | 0.241 | 3 | |

| Uroplatus phantasticus | yes | 0.241 | 6 | |

| Chondrodactylus turneri | no | |||

| Phyllopezus pollicaris | yes | 0.247 | 8 | |

| Stenodactylus mauritanicus | yes | 0.575 | 1 | |

| Diplodactylus vittatus | yes | 0.940 | 3 | |

| Iguanidae | Anolis carolinensis | yes | 0.308 | 11 |

| Basiliscus vitttatus | yes | 0.226 | 9 | |

| Corytophanes cristatus | yes | 0.271 | 7 | |

| Crotaphytus bicinctores | yes | 0.326 | 5 | |

| Crotaphytus collaris | yes | 0.376 | 5 | |

| Ctenosaura quinquecarinata | no | |||

| Ctenosaura similis | yes | 0.433 | 7 | |

| Dipsosaurus dorsalis | yes | 0.524 | 2 | |

| Gambelia wislizenii | yes | 0.236 | 5 | |

| Iguana Iguana | yes | 0.371 | 1 | |

| Leiocephalus schreibersi | yes | 0.326 | 0 | |

| Phrynosoma platyrhinos | yes | 0.340 | 3 | |

| Sauromalus ater | yes | 0.616 | −2 | |

| Sceloporus magister | yes | 0.286 | 7 | |

| Sceloporus malachiticus | yes | 0.175 | −1 | |

| Tropidurus hispidus | no | |||

| Uta stansburiana | yes | 0.703 | 3 | |

| Anolis coelestinus | yes | 0.467 | 4 | |

| Anolis cristatellus | yes | 0.370 | 9 | |

| Anolis cybotes | yes | 0.467 | 7 | |

| Anolis equestris | yes | 0.439 | 8 | |

| Anolis gingivinus | yes | 0.467 | 7 | |

| Anolis hendersoni | yes | 0.467 | 7 | |

| Anolis noblei | yes | 0.467 | 10 | |

| Anolis pogus | yes | 0.431 | 9 | |

| Anolis roquet | yes | 0.467 | 6 | |

| Anolis sagrei | yes | 0.396 | 5 | |

| Basiliscus plumifrons | yes | 0.226 | 2 | |

| Brachylophus fasciatus | yes | 0.470 | 0 | |

| Crotaphytus insularis | yes | 0.206 | 2 | |

| Chalarodon madagascariensis | yes | 0.467 | 4 | |

| Leiocephalus personatus | yes | 0.389 | -2 | |

| Oplurus cyclurus | yes | 0.467 | 0 | |

| Oplurus fierinensis | yes | 0.467 | 0 | |

| Oplurus grandidieri | yes | 0.467 | 2 | |

| Oplurus quadrimaculatus | yes | 0.467 | 0 | |

| Chameleolis barbatus | yes | 0.467 | 4 | |

| Pythonidae | Aspidites ramsayi | yes | 0.131 | 3 |

| Bothrochilus boa | yes | 0.060 | 8 | |

| Broghammerus reticulatus | yes | 0.060 | 16 | |

| Broghammerus timoriensis | yes | 0.060 | 2 | |

| Leiopython albertisii | yes | 0.060 | 2 | |

| Liasis mackloti | yes | 0.078 | 9 | |

| Morelia amethistina | yes | 0.078 | 9 | |

| Morelia boeleni | yes | 0.078 | 2 | |

| Morelia spilota | yes | 0.769 | 13 | |

| Morelia viridis | yes | 0.072 | 5 | |

| Python breitensteini | yes | 0.071 | 10 | |

| Python brongersmai | yes | 0.071 | 8 | |

| Python regius | yes | 0.060 | 9 | |

| Python sebae | yes | 0.132 | 16 | |

| Boidae | Calabaria reinhardtii | yes | 0.084 | 10 |

| Acrantophis dumerili | yes | 0.084 | 9 | |

| Epicrates cenchria | yes | 0.060 | 8 | |

| Eunectes notaeus | yes | 0.206 | 14 | |

| Corallus caninus | yes | 0.059 | 6 | |

| Corallus hortulanus | yes | 0.103 | 14 | |

| Gongylophis colubrinus | no | |||

| Boa constrictor | yes | 0.171 | 13 | |

| Crocodylidae | Osteolaemus tetraspis | yes | 0.201 | 15 |

| Alligatoridae | Paleosuchus palpebrosus | yes | 0.096 | 12 |

| Anguidae | Barisia imbricata | yes | 0.58–0.66 | 2 |

| Agamidae | Acanthocercus atricollis | yes | 0.397 | 6 |

| Agama aculeata | yes | 0.465 | 5 | |

| Agama agama | yes | 0.208 | 14 | |

| Agama doriae | yes | 0.403 | 0 | |

| Hydrosaurus amboinensis | yes | 0.351 | 4 | |

| Hydrosaurus weberi | yes | 0.351 | 2 | |

| Japalura tricarinata | yes | 0.462 | 2 | |

| Leiolepis belliana | yes | 0.113 | 1 | |

| Leiolepis guttata | yes | 0.113 | 1 | |

| Leiolepis reevesii | yes | 0.113 | −2 | |

| Physignathus cocincinus | yes | 0.208 | 4 | |

| Intellagama lesueurii | yes | 0.885 | 11 | |

| Pogona vitticeps | yes | 0.151 | 10 | |

| Pseudotrapelus sinaitus | yes | 0.087 | 7 | |

| Chlamydosaurus kingi | yes | 0.116 | 6 | |

| Trapelus savignii | yes | 0.429 | 5 | |

| Acanthosaura lepidogaster | yes | 0.455 | 4 | |

| Uromastyx acanthinura | yes | 0.073 | 6 | |

| Uromastyx benti | yes | 0.058 | −1 | |

| Draco maculatus | yes | 0.455 | 3 | |

| Calotes jubatus | yes | 0.455 | 2 | |

| Japalura splendida | no | |||

| Uromastyx geyri | no | |||

| Uromastyx dispar | no | |||

| Uromastyx ornata | no | |||

| Acanthosaura capra | no | |||

| Draco volans | no | |||

| Calotes emma | no | |||

| Gonocephalus chamaeleontinus | no | |||

| Scincidae | Acontias percivalii | yes | 0.279 | 9 |

| Bellatorias frerei | yes | 0.131 | 9 | |

| Egernia depressa | yes | 0.126 | 9 | |

| Corucia zebrata | yes | 0.064 | 1 | |

| Chalcides sexlineatus | yes | 0.278 | 11 | |

| Lamprolepis smaragdina | yes | 0.281 | 5 | |

| Mochlus sundevalli | yes | 0.416 | 9 | |

| Mabuya multifasciata | yes | 0.324 | 11 | |

| Mabuya quinquetaeniata | no | |||

| Lepidothyris fernandi | yes | 0.411 | 9 | |

| Scincus scincus | yes | 0.356 | 9 | |

| Trachylepis affinis | no | |||

| Trachylepis elegans | yes | 0.293 | 7 | |

| Trachylepis margaritifera | yes | 0.293 | 8 | |

| Trachylepis perrotetii | no | |||

| Tiliqua gigas | yes | 0.226 | 10 | |

| Tiliqua scincoides | yes | 0.912 | 11 | |

| Tribolonotus gracilis | yes | 0.064 | 9 | |

| Tropidophorus baconi | no | |||

| Eumeces schneideri | yes | 0.438 | 7 | |

| Eumeces algeriensis | yes | 0.405 | 10 | |

| Voeltzkowia rubrocaudata | yes | 0.264 | 9 | |

| Gerrhosauridae | Zonosaurus karsteni | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 8 |

| Zonosaurus laticaudatus | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 10 | |

| Zonosaurus madagascariensis | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 6 | |

| Zonosaurus maximus | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 7 | |

| Zonosaurus ornatus | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 10 | |

| Zonosaurus quadrilineatus | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 6 | |

| Gerrhosaurus flavigularis | no | |||

| Gerrhosaurus major | yes | 0.036–0.430 | 9 | |

| Gerrhosaurus nigrolineatus | no | |||

| Tracheloptychus petersi | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 8 | |

| Varanidae | Varanus acanthurus | yes | 0.119 | 9 |

| Varanus beccarii | no | |||

| Varanus boehmei | yes | 0.119 | 9 | |

| Varanus exanthematicus | yes | 0.037 | 9 | |

| Varanus jobiensis | yes | 0.119 | 9 | |

| Varanus macraei | no | |||

| Varanus melinus | no | |||

| Varanus prasinus | yes | 0.119 | 9 | |

| Varanus rudicolis | no | |||

| Varanus salvator | yes | 0.119 | 14 | |

| Varanus timorensis | yes | 0.119 | 8 | |

| Varanus yuwonoi | no | |||

| Lacertidae | Acanthodactylus longipes | yes | 0.458 | 11 |

| Adolfus jacksoni | yes | 0.391 | 3 | |

| Heliobolus spekii | yes | 0.474 | 3 | |

| Holaspis guentheri | yes | 0.325 | 5 | |

| Latastia longicaudata | yes | 0.492 | 10 | |

| Takydromus sexlineatus | yes | 0.325 | 5 | |

| Teiidae | Ameiva ameiva | no | ||

| Holcosus undulatus | yes | 0.368 | 14 | |

| Aspidoscelis deppei | yes | 0.366 | 3 | |

| Cnemidophorus lemniscatus | no | |||

| Tupinambis merianae | yes | 0.150 | 12 | |

| Tupinambis rufescens | yes | 0.145 | 12 | |

| Cordylidae | Cordylus beraduccii | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 3 |

| Cordylus tropidosternum | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 3 | |

| Platysaurus guttatus | no | |||

| Platysaurus intermedius | yes | 0.019–0.275 | 5 | |

| Platysaurus torquatus | yes | 0.018–0.271 | 3 | |

| Colubridae | Ahaetulla nasuta | yes | 0.056 | 10 |

| Ahaetulla prasina | yes | 0.056 | 8 | |

| Coelognathus helena | no | |||

| Coelognathus radiatus | no | |||

| Chrysopelea ornata | no | |||

| Boiga cynodon | yes | 0.075 | 8 | |

| Boiga dendrophila | no | |||

| Coluber constrictor | yes | 0.067 | 12 | |

| Cyclophiops major | yes | 0.060 | 8 | |

| Dasypeltis fasciata | yes | 0.115 | 6 | |

| Dasypeltis medici | yes | 0.157 | 8 | |

| Dasypeltis scabra | yes | 0.401 | 8 | |

| Dromicodryas bernieri | yes | 0.134 | 7 | |

| Elaphe bimaculata | yes | 0.099 | 11 | |

| Elaphe carinata | no | |||

| Erpeton tentaculatum | yes | 0.056 | 8 | |

| Euprepiophis mandarinus | yes | 0.332 | 8 | |

| Gonyosoma oxycephala | yes | 0.342 | 4 | |

| Homalopsis buccata | yes | 0.134 | 7 | |

| Lampropeltis alterna | yes | 0.073 | 8 | |

| Lampropeltis getula | yes | 0.122 | 11 | |

| Lampropeltis pyromelana | yes | 0.116 | 8 | |

| Lampropeltis triangulum | no | |||

| Lamprophis fuliginosus | yes | 0.482 | 9 | |

| Langaha madagascariensis | yes | 0.134 | 7 | |

| Leioheterodonn geayi | yes | 0.134 | 8 | |

| Leioheterodon madagascariensis | yes | 0.134 | 7 | |

| Leioheterodon modestus | yes | 0.134 | 7 | |

| Liophidium chabaudi | yes | 0.134 | 6 | |

| Madagascarophis citrinus | no | |||

| Madagascarophis colubrinus | yes | 0.134 | 8 | |

| Nerodia taxispilota | yes | 0.100 | 13 | |

| Oligodon chinensis | yes | 0.151 | 9 | |

| Oligodon formosanus | yes | 0.135 | 6 | |

| Oocatochus rufodorsatus | yes | 0.073 | 10 | |

| Opheodrys aestivus | yes | 0.139 | 9 | |

| Oreocryptophis porphyracea | no | |||

| Orthriophis moellendorffi | yes | 0.290 | 6 | |

| Orthriophis taeniurus friesi | no | |||

| Psammophis mossambicus | yes | 0.140 | 9 | |

| Psammophylax multisquamis | no | |||

| Pseudelaphe flavirufa | yes | 0.059 | 6 | |

| Rhadinophis frenatum | yes | 0.345 | 6 | |

| Rhamphiophis rostratus | no | |||

| Rhamphiophis rubropunctatus | no | |||

| Rhinocheilus lecontei | yes | 0.149 | 9 | |

| Rhynchophis boulengeri | yes | 0.342 | 6 | |

| Spalerosophis diadema | no | |||

| Thamnophis marcianus | yes | 0.369 | 13 | |

| Thamnophis sauritus | yes | 0.358 | 12 | |

| Thamnophis sirtalis | yes | 0.662 | 13 | |

| Xenochrophis vittata | yes | 0.290 | 7 | |

| Telescopus beetzi | no | |||

| Heterodon nasicus | yes | 0.178 | 11 | |

| Dendrelaphis cyanochloris | yes | 0.056 | 7 | |

| Dendrelaphis formosus | yes | 0.056 | 10 | |

| Dinodon flavozonatum | yes | 0.344 | 6 | |

| Pantherophis vulpinus | yes | 0.155 | 10 | |

| Philothamnus semivariegatus | yes | 0.731 | 9 | |

| Viperidae | Atheris ceratophora | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 2 |

| Bitis arietans | yes | 0.101–0.671 | 11 | |

| Bitis nasicornis | yes | 0.019–0.264 | 4 | |

| Bitis rhinoceros | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 9 | |

| Cerastes cerastes | yes | 0.035–0.395 | 7 | |

| Crotalus atrox | yes | 0.057–0.524 | 7 | |

| Crotalus cerastes | yes | 0.026–0.326 | 8 | |

| Cryptelytrops albolabris | no | |||

| Cryptelytrops fasciatus | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 4 | |

| Cryptelytrops insularis | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 4 | |

| Cryptelytrops purpureomaculatus | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 2 | |

| Trimeresurus fucatus | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 4 | |

| Trimeresurus nebularis | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 4 | |

| Trimeresurus poperium | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 3 | |

| Trimeresurus puniceus | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 4 | |

| Tropidolaemus subannulatus | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 7 | |

| Tropidolaemus wagleri | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 3 | |

| Viridovipera gumprechti | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 0 | |

| Viridovipera vogeli | yes | 0.018–0.254 | 0 | |

| Deinagkistrodon acutus | yes | 0.020–0.267 | 10 | |

| Agkistrodon contortrix | yes | 0.082–0.620 | 8 | |

| Elapidae | Acanthopis praelongus | yes | 0.126 | −1 |

| Aspidelaps lubricus | yes | 0.405 | 1 | |

| Dendroaspis angusticeps | yes | 0.418 | 3 | |

| Naja atra | yes | 0.216 | 3 | |

| Naja kaouthia | yes | 0.381 | 5 | |

| Naja naja | yes | 0.170 | 9 | |

| Xenopeltidae | Xenopeltis unicolor | yes | 0.190 | 7 |

| Sphenodontidae | Sphenodon punctatus | yes | 0.072–0.607 | 4 |

References

- Dukes, J.S.; Mooney, H.A. Does global change increase the success of biological invaders? Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Evinver, V.T.; Jeschke, J.M.; Pace, M.L. Understanding the long-term effects of species invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, A. Are modern biological invasions an unprecedented form of global change? Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulme, P.E. Beyond control: Wider implications for the management of biological invasions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Zuniga, R.; Morrison, D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puth, L.M.; Post, D.M. Studying invasion: Have we missed the boat? Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, P.E.; Pyšek, P.; Nentwig, W.; Vila, M. Will threat of biologicalinvasions unite the European Union? Science 2009, 324, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, W.C.; Witmer, G.W. Invasive vertebrate species and the challenges of management. In Proceedings of the 26th Vertebrate Pest Conference, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3–6 March 2015; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Elvira, B.; Almodovar, A. Freshwater fish introductions in Spain: Facts and figures at the beginning of the 21st century. J. Fish Biol. 2005, 59, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, J.M.; Strayer, D.L. Invasion success of vertebrates in Europe and North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 102, 7198–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, F. Impacts from invasive reptiles and amphibians. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015, 46, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, F. Alien Reptiles and Amphibians: A Scientific Compedium and Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, A.; Bulcroft, K. Pets and urban life. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copping, J. Reptiles now more Popular Pets than Dogs. The Telegraph. 22 November 2008. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/3500882/Reptiles-now-more-popular-pets-than-dogs.html (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Virata, J. Pet Reptile Product Sales Reach $383 million in 2016. Reptiles Magazine. 17 December 2017. Available online: http://www.reptilesmagazine.com/Pet-Reptile-Product-Sales-Reach-383-Million-In-2016/ (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Rodda, G.H.; Fritts, T.H.; Chiszar, D. The disappearance of Guam’s wildlife. Bioscience 1997, 47, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telecky, T.M. United States import and export of live turtles and tortoises. Turt. Tortoise Newsl. 2001, 4, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cadi, A.; Joly, P. Competition for basking places between the endangered European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis galloitalica) and the introduced red-eared turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Can. J. Zool. 2003, 81, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadi, A.; Joly, P. Impact of the introduction of the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) on survival rates of the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis). Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 2511–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teillac-Deschamps, P.; Prevot-Julliard, A.C. Impact of exotic slider turtles on freshwater communities: An experimental approach. In First European Congress of Conservation Biology; Book Ofabstracts; Society for Conservation Biology: Heger, Germany, 2006; pp. 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bomford, M.; Kraus, F.; Barry, S.C.; Lawrence, E. Predicting establishment success for alien reptiles and amphibians: A role for climate matching. Biol. Invasions 2009, 11, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, W.; Bomford, M.; Cassey, P. Managing the risk of exotic vertebrates incursions in Australia. Wildl. Res. 2011, 38, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, R.; Massemin, D.; Kowarik, I. Non-invasive invaders from the Caribbean: The status of Johnstone’s Whistling frog (Eleutherodactylus johnstonei) ten years after its introduction to Western French Guiana. Biol. Invasions 2011, 13, 1767–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, A. The volume of the ornamental fish trade, International transport of live fish in the ornamental aquatic industry. Ornam. Fish Int. J. 2007, 2, 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Patoka, J.; Kalous, L.; Kopecký, O. Imports of ornamental crayfish: The firstdecade from the Czech Republic’ys perspective. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2015, 416, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalous, L. (Naše) nepůvodní a invazní druhy ryb. Živa 2018, 5, 266–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kopecký, O.; Patoka, J.; Kalous, L. Establishment risk and potential invasiveness of the selected exotic amphibians from pet trade in the European Union. J. Nat. Conserv. 2016, 31, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, O.; Kalous, L.; Patoka, J. Establishment risk from pet-trade freshwater turtles in the European Union. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2013, 410, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nentwig, W.; Kühnel, E.; Bacher, S. A generic impact-scoring systém applied to alien mammals in Europe. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomford, M. Risk Assessment Models for Establishment of Exotic Vertebrates in Australia and New Zealand; Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, G.H.; Villizzi, L.; Tidbury, H.; Stebbing, P.D.; Tarkan, A.S.; Miossec, L.; Goulletquer, P. Development of a generic decision-support tool for identifying potentially invasive aquatic taxa: AS-ISK. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2016, 7, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, G.H.; Bianco, P.G.; Bogutskaya, N.G.; Eros, T.; Falka, I.; Ferreira, M.T. To be, or not to be, a non-native freshwater fish? J. Appl. Ichtyol. 2005, 21, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumschick, S.; Richardson, D.M. Species-based risk assessments forbiological invasions: Advances and challenges. Divers. Distrib. 2013, 19, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassey, P.; Blackburn, T.M.; Jones, K.E.; Lockwood, J.L. Mistakes in theanalysis of exotic species establishment: Source pool designation andcorrelates of introduction success among parrots (Aves: Psittaciformes) of theworld. J. Biogeogr. 2004, 31, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, G.H.; Vilizzi, L.; Mumford, J.; Fenwick, G.V.; Godard, M.J.; Gozlan, R.E. Calibration of FISK, an Invasiveness Screening Tool for Nonnative Freshwater Fish. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilizzi, L.; Copp, G.H.; Adamovich, B.; Almeida, D.; Chan, J.; Davison, P.I.; Dembski, S.; Ekmekçi, F.G.; Ferincz, Á.; Forneck, S.C.; et al. A global review and meta-analysis of applications of the freshwater Fish Invasiveness Screening Kit. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2019, 29, 529–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficetola, G.F.; Thuiller, W.; Miaud, C. Prediction and validation of thepotential global distribution of a problematic alien invasive species—The American bullfrog. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, C.S.; Lodge, D.M. Progress in invasion biology: Predictinginvaders. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poessel, S.A.; Beard, K.H.; Callahan, C.M.; Ferreira, R.B.; Stevenson, E.T. Biotic acceptance in introduced amphibians and reptiles in Europe and North America. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.A.T.; Laverty, C.; Lennon, J.J.; Barrios-O’Neill, D.; Mensink, P.J.; Britton, J.R.; Medoc, V.; Boets, P.; Alexander, M.E.; Taylor, N.G.; et al. Invader Relative Impact Potential: A new metric to understand and predict the ecological impacts of existing, emerging and future invasive alien species. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, T.M.; Pyšek, P.; Bacher, S.; Carlton, J.T.; Duncan, R.P.; Jarošík, V.; Wilson, J.R.U.; Richardson, D.M. A proposed unified framework for biological invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patoka, J.; Petrtýl, M.; Kalous, L. Garden ponds as potential introduction pathway of ornamental crayfish. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2014, 414, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmens, B.X.; Buhle, E.R.; Salomon, A.K.; Pattengill-Semmens, C.V. A hotspot of non-native marine fish: Evidence for the aquarium trade as an invasion pathway. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 266, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, I.C.; Rixon, C.A.M.; MacIsaac, H.J. Popularity and propagule pressure: Determinants of introduction and establishment of aquarium fish. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Jarošík, V.; Hulme, P.E.; Pergl, J.; Hejda, M. A global assessment of invasive plant impacts on resident species, communities and ecosystems: The interaction of impact measures, invading species’ traits and environment. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, G.H.; Vilizzi, L.; Gozlan, R.E. The demography of introduction pathways, propagule pressure and occurrences of non-native freshwater fish in England. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2010, 20, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrel, A.; van der Meijden, A. An analysis of the live reptile andamphibian trade in the USA compared to the global trade in endangeredspecies. Herpetol. J. 2014, 24, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, M.; Fitter, A. The characters of successful invaders. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 78, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, E.R.; Baker, S.E.; MacDonald, D.W. Global trade in exotic pets 2006–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodenough, A.E. Are the ecological impacts of alien speciesmisrepresented? A review of the native good, alien bad philosophy. Commun. Ecol. 2010, 11, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.R.; Hammerson, G.A.; Santos-Barrera, G. Thamnophis Sirtalis; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, D.G. Review: Discrepant usage of the term “ovoviviparity” in the herpetological literature. Herpetol. J. 1994, 4, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, R. Does Viviparity Evolve in Cold Climate Reptiles Because Pregnant Females Maintain Stable (Not High) Body Temperatures? Evolution 2004, 28, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speybroeck, J.; Crochet, P.-A. Species list of the European herpetofauna—A tentative update. Podarcis 2007, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Edgehouse, M.J. Garter Snake (Thamnophis) Natural History: Food Habits and Interspecific Aggression. Ph.D. Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli, L.; Filippi, E.; Capula, M. Geographic variation in diet composition of the Grass Snake (Natrix natrix) along the mainland and an island of Italy: The effect of habitat type and interference with potential competitors. Herpetol. J. 2005, 15, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli, L.; Capizzi, D.; Filippi, E.; Anibaldi, C.; Rugiero, L.; Capula, M. Comparative Diets of Three Populations of an Aquatic Snake (Natrix Tessellata, Colubridae) from Mediterranean Streams with Different Hydric Regimes. Copeia 2007, 2, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, X.; González-Solís, J.; Llorente, G.A. Variation in the diet of the viperine snake Natrix maura in relation to prey availability. Ecography 2000, 23, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, E.D., III; Brodie, E.D., Jr. Tetrodotoxin resistance in garter snakes: An evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey. Evolution 1990, 44, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, S.; Solarz, W.; Chiron, F.; Clergeau, P.; Shirley, S. Alien birds, amphibians and reptiles of Europe. In Handbook of Alien Species in Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Münch, D. Ausgesetzte Amphibien—Und Reptilienarten in Dortmund und weitere herpetologische Kurzmitteilungen. Dortm. Beitr. Landeskd. Naturwissenschaftliche Mitt. 1992, 26, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tallowin, O.; Parker, F.; O’Shea, M.; Vanderduys, E.; Wilson, S.; Shea, G.; Hobson, R. Morelia Spilota; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Shine, R.; Williams, A. Spatial ecology of a threatened python (Morelia spilota imbricata) and the effects of anthropogenic habitat change. Aust. Ecol. 2005, 30, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shine, R.; Fitzgerald, M. Large snakes in a mosaic rural landscape: The ecology of carpet pythons Morelia spilota (Serpentes: Pythonidae) in coastal eastern Australia. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 76, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Swan, G. A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia; Reed New Holland Publishers: Chatswood, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Slip, D.; Shine, R. Habitat Use, Movements and Activity Patterns of Free-Ranging Diamond Pythons, Morelia-Spilota-Spilota (Serpentes, Boidae)—A Radiotelemetric Study. Wildl. Res. 1988, 15, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Heinsohn, R. Geographic range, population structure and conservation status of the green python (Morelia viridis), a popular snake in the captive pet trade. Aust. J. Zool. 2007, 55, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaric, I.; Civjanovic, G. The Tens Rule in Invasion Biology: Measure of a True Impactor Our Lack of Knowledge and Understanding? Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 79–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Family | Risk Score | Risk Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diplodactylus vittatus | Gekkonidae | 0.940 | extreme |

| Underwoodisaurus milii | Gekkonidae | 0.920 | extreme |

| Tiliqua scincoides | Scincidae | 0.912 | extreme |

| Intellagama lesueurii | Agamidae | 0.885 | extreme |

| Morelia spilota | Pythonidae | 0.769 | serious |

| Philothamnus semivariegatus | Colubridae | 0.731 | serious |

| Chamaeleo dilepis | Chamaeleonidae | 0.730 | serious |

| Uta stansburiana | Iguanidae | 0.703 | serious |

| Thamnophis sirtalis | Colubridae | 0.662 | serious |

| Chamaeleo calyptratus | Chamaeleonidae | 0.624 | serious |

| Barisia imbricata | Anguidae | 0.582–0.663 | serious |

| Sauromalus ater | Iguanidae | 0.616 | serious |

| Trioceros bitaeniatus | Chamaeleonidae | 0.586 | serious |

| Cyrtopodion scabrum | Gekkonidae | 0.577 | serious |

| Stenodactylus mauritanicus | Gekkonidae | 0.575 | serious |

| Species | Family | Risk Score |

|---|---|---|

| Python sebae | Pythonidae | 16 |

| Malayopython reticulatus | Pythonidae | 16 |

| Osteolaemus tetraspis | Crocodylidae | 15 |

| Agama agama | Agamidae | 14 |

| Eunectes notaeus | Boidae | 14 |

| Varanus salvator | Varanidae | 14 |

| Corallus hortulanus | Boidae | 14 |

| Holcosus undulatus | Teiidae | 14 |

| Hemidactylus frenatus | Gekkonidae | 13 |

| Lepidodactylus lugubris | Gekkonidae | 13 |

| Morelia spilota | Pythonidae | 13 |

| Boa constrictor | Boidae | 13 |

| Nerodia taxispilota | Colubridae | 13 |

| Thamnophis marcianus | Colubridae | 13 |

| Thamnophis sirtalis | Colubridae | 13 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kopecký, O.; Bílková, A.; Hamatová, V.; Kňazovická, D.; Konrádová, L.; Kunzová, B.; Slaměníková, J.; Slanina, O.; Šmídová, T.; Zemancová, T. Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK). Diversity 2019, 11, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/d11090164

Kopecký O, Bílková A, Hamatová V, Kňazovická D, Konrádová L, Kunzová B, Slaměníková J, Slanina O, Šmídová T, Zemancová T. Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK). Diversity. 2019; 11(9):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/d11090164

Chicago/Turabian StyleKopecký, Oldřich, Anna Bílková, Veronika Hamatová, Dominika Kňazovická, Lucie Konrádová, Barbora Kunzová, Jana Slaměníková, Ondřej Slanina, Tereza Šmídová, and Tereza Zemancová. 2019. "Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK)" Diversity 11, no. 9: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/d11090164

APA StyleKopecký, O., Bílková, A., Hamatová, V., Kňazovická, D., Konrádová, L., Kunzová, B., Slaměníková, J., Slanina, O., Šmídová, T., & Zemancová, T. (2019). Potential Invasion Risk of Pet Traded Lizards, Snakes, Crocodiles, and Tuatara in the EU on the Basis of a Risk Assessment Model (RAM) and Aquatic Species Invasiveness Screening Kit (AS-ISK). Diversity, 11(9), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/d11090164