Abstract

The title compound was synthesized in near-quantitative yield using nucleophilic aromatic substitution of 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)diphenol (BPAF) with perfluoropyridine (PFP). The purity and structure were determined by NMR (1H, 13C, 19F), GC–EIMS, and single-crystal X-ray crystallography.

1. Introduction

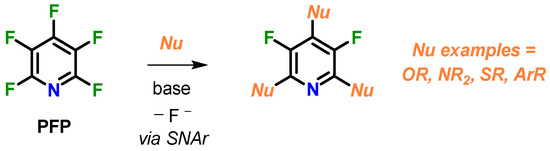

Perfluoropyridine (PFP) is a versatile starting material for nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr), reacting with a broad range of O-, N-, S, and C-nucleophiles via exclusive attack at the 4-para-position [1,2] (Scheme 1). Sequential addition to the 2,6-ortho-positions can also be accomplished leaving the 3,5-meta-fluorines intact. Furthermore, PFP has demonstrated utility as a protecting group for phenols [3,4], fluorinating reagent [5,6] and can also be defluorinated via site-selective catalysis [7,8]. Motivation for incorporating PFP into polymer frameworks led to the development of a pool of new fluoropolymer architectures, including highly processable polyarylethers, fluorosilicones, dendrimers, and high-char-yield resins for demanding aerospace applications [9], in addition to expanding the utility of hydrofluoroethers (HFEs) [10]. These unique materials have shown marked improvement over conventional state-of-the-art polymers in processabilty, mechanical strength, and compatibility with hybrid composites, while retaining high-temperature resistance. More recently, PFP was used for the mechanochemical synthesis of perfluoropolyether oligomers, which expands its utility for solvent-free polymerizations [11]. As an extension of this work, herein, we detail the synthesis and structural characterization of a PFP end-capped bisphenol, a new type of monomer for SNAr polymerizations.

Scheme 1.

Perfluoropyridine as a regioselective electrophile.

2. Results and Discussion

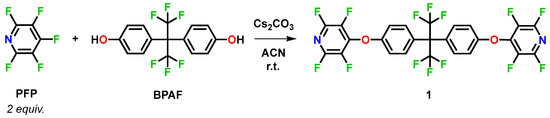

The synthesis of 4,4′-(((perfluoropropane-2,2-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))-bis(2,3,5,6-tetrafluoropyridine) (1) was accomplished by nucleophilic aromatic substitution of pentafluoropyridine (PFP) with 4,4′-(perfluoropropane-2,2-diyl)diphenol (BPAF) using stoichiometric cesium carbonate in acetonitrile at room temperature (Scheme 2). Reaction monitoring by 19F-NMR showed the regioselective quantitative conversion of the para-F (δ −130 ppm) from PFP exclusively to the set of ortho- and meta-F multiplets at δ −88.1–−88.2 and δ −153.7–−153.9 (see supplementary materials). Upon filtration of the carbonate salts followed by aqueous workup, compound 1 was obtained as a white, waxy solid in 95% overall isolated yield, requiring no further purification. GC–MS confirmed the purity >98% with an observed molecular ion at [M − CF3•]+ at m/z = 565.

Scheme 2.

Base-promoted synthesis of compound 1 from PFP and BPAF.

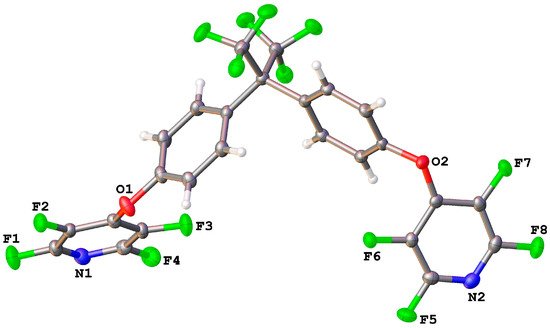

Crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction were obtained by dissolution of 1 in hot ethanol followed by cooling and slow evaporation. The molecular structure of 1 (Figure 1) shows the expected BPAF core with two PFP groups attached via ether linkages. The least-squares planes of the rings of the BPAF core are inclined at an angle of 73.47° (0.04), with the attached PFP rings inclined at angles of 68.17° (0.04) (N1PFP) and 63.39° (0.04) (N2PFP) to their respective BPAF core rings.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of 1. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level.

3. Materials and Methods

Chemicals and solvents were purchased as reagent grade through commercial suppliers. 1H-, 13C{1H}-, and 19F-NMR spectra were recorded on a Jeol 500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm), and the residual solvent peak was used as an internal reference: proton (chloroform δ 7.26), carbon (chloroform, C{D} triplet, δ 77.0 ppm), and fluorine (CFCl3 δ 0.00). NMR data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity, coupling constants (Hz), and integration. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis was performed on an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph coupled to an Agilent 5975C electron impact mass spectrometer with initial 2 min temperature hold at 80 °C, followed by a temperature gradient of 80 to 250 °C at 15 °C/min.

3.1. Synthesis of 4,4′-(((perfluoropropane-2,2-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))-bis(2,3,5,6-tetrafluoropyridine) (1)

Cesium carbonate (10.7 g, 32.7 mmol), pentafluoropyridine (5.89 g, 34.8 mmol), and 4,4′-(perfluoropropane-2,2-diyl)diphenol (4.97 g, 14.8 mmol) were combined in acetonitrile (30 mL) and allowed to stir for 48 h at room temperature. The reaction was monitored by 19F-NMR until 100% conversion of the desired product was observed. The solution was vacuum-filtered to remove carbonate salts and washed with diethyl ether (100 mL). The filtrate was combined with saturated ammonium chloride (100 mL) and the aqueous layer was extracted with diethyl ether (2 × 50 mL). The combined organic fractions were washed with saturated brine (1 × 100 mL), dried with magnesium sulfate, vacuum-filtered, concentrated using rotary evaporation, and placed under high vacuum, affording a white, waxy solid (8.89 g, 95%). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 7.44–7.20 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 4H), 7.10–7.08 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 4H); 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz) δ 156.1, 145.3–145.1 (m), 143.6 (sept, J = 11.1 Hz, (CF3)2C=), 144.5 (dtd, J = 252, 16.2, 3.02 Hz), 137.5–137.2 (m), 136.3 (ddt, J = 252, 20.1, 6.05 Hz), 132.1, 129.8, 123.0 (q, J = 283 Hz, –CF3), 116.4; 19F-NMR (CDCl3, 471 MHz) δ −64.2 (s, 6F) −88.1–−88.2 (m, 4F) −153.7–−153.9 (m, 4F); GC–EIMS (70 eV) m/z (% relative intensity) 565 ([M − CF3•]+, 100), 379 (15), 330 (50), 233 (80), 201 (15), 183 (40), 152 (40), 138 (40), 100 (40), 69 (10).

3.2. Single-Crystal XRD Determination

The single crystal X-ray diffraction studies were carried out on a Rigaku Synergy-i single-crystal diffractometer equipped with a Mo Kα radiation source (λ = 0.71073) and a Bantam HyPIX-3000 direct photon-counting detector. A 0.379 × 0.298 × 0.242 mm3 translucent colorless prism crystal was mounted on a Cryoloop with Paratone-N oil. Data were collected in a nitrogen gas stream at 100.00(15) K using ϖ scans. The crystal-to-detector distance was 40 mm using an exposure time of 10 s with a scan width of 0.50°. Data collection was 100.0% complete to 25.242° in θ. A total of 81,813 reflections were collected. Of these, 5176 reflections were found to be symmetry-independent, with an Rint of 0.0340. Indexing and unit cell refinement indicated a primitive orthorhombic lattice. The space group was found to be Pbca. The data were integrated using the CrysAlisPro software program (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, 2020, 1.171.42.49) and scaled using an empirical absorption correction implemented in the SCALE 3 ABSPACK software program, as well as a numerical absorption correction based on Gaussian integration over a multifaceted crystal model. Solution by direct methods (SHELXT-2014) produced a complete phasing model consistent with the proposed structure. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically by full-matrix least squares (SHELXL- 2008). All carbon bonded hydrogen atoms were placed using a riding model with their positions constrained relative to their parent atom using the appropriate HFIX command in SHELXL.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information is available online: 1H-, 19F-, and 13C-NMR spectra and GC–MS for 1.

Author Contributions

Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and data curation, K.D.T., N.J.W., G.J.B. and S.T.I.; writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing, K.D.T., N.J.W., G.J.B. and S.T.I.; conceptualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, S.TI. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR).

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2238883 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK, fax: +44-1223-336033.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Neumann, C.N.; Hooker, J.M.; Ritter, T. Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution with 19F− and 18F−. Nature 2016, 534, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandford, G. Perfluoroheteroaromatic Chemistry: Multifunctional Systems from Perfluorinated Heterocycles by Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution Processes. In Halogenated Heterocycles: Synthesis, Application and Environment; Iskra, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–31. ISBN 978-3-642-43950-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer, T.; Houck, M.; Corley, C.A.; Iacono, S.T. Theoretical Explanation of Reaction Site Selectivity in the Addition of a Phenoxy Group to Perfluoropyridine. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 9450–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brittain, W.D.G.; Cobb, S.L. Tetrafluoropyridyl (TFP): A General Phenol Protecting Group Readily Cleaved under Mild Conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 2110–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.B.; Sandford, G.; Korn, S.R.; Yufit, D.S.; Howard, J.A.K. New fluoride ion reagent from pentafluoropyridine. J. Fluor. Chem. 2005, 126, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain, W.G.D.; Cobb, S.L. Carboxylic Acid Deoxyfluorination and One-Pot Amide Bond Formation Using Pentafluoropyridine (PFP). Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 5793–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senaweera, S.M.; Singh, A.; Weaver, J.D. Photocatalytic Hydrodefluorination: Facile Access to Partially Fluorinated Aromatics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3002–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froese, R.D.J.; Whiteker, G.T.; Peterson, T.H.; Arriola, D.J.; Renga, J.M.; Shearer, J.W. Computational and Experimental Studies of Regioselective SNAr Halide Exchange (Halex) Reactions of Pentachloropyridine. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 10672–10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, R.; Geniza, I.; Iacono, S.T.; Friesen, C.M.; Jennings, A.R. Perfluoropyridine: Discovery, Chemistry, and Applications in Polymers and Material Science. Molecules 2022, 27, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freisen, C.M.; Newton, J.; Hardera, J.; Iacono, S.T. Hydrofluoroethers (HFEs): A History of Synthesis. In Perfluoroalkyl Substances: Synthesis, Applications, Challenges and Regulations; Améduri, B., Ed.; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 166–356. [Google Scholar]

- Freisen, C.M.; Kelly, A.R.; Iacono, S.T. Shaken Not Stirred: Perfluoropyridine Polyalkylether Prepolymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 10970–10979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).