Challenges in Balancing Hemostasis and Thrombosis in Therapy Tailoring for Hemophilia: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

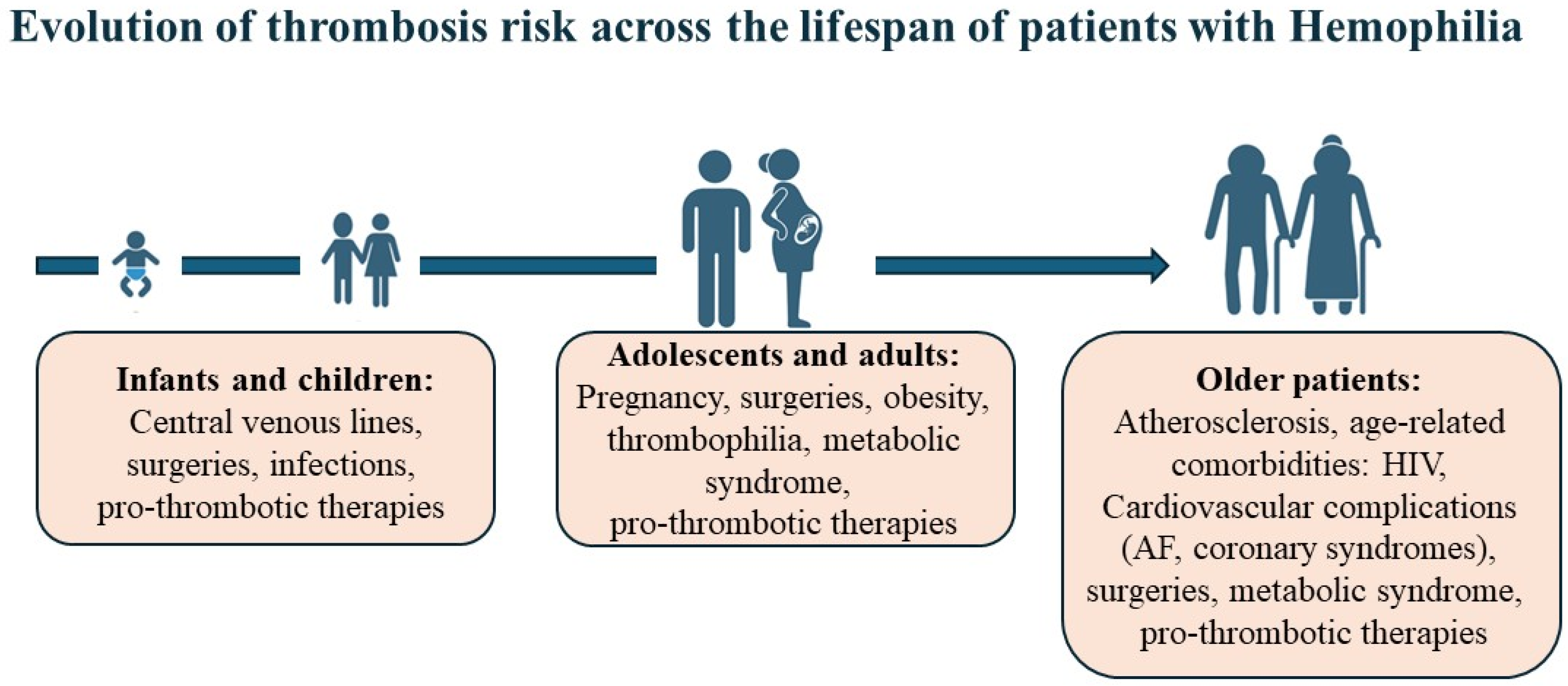

2. Thrombosis in Hemophilia: The Emerging Challenge of Aging and Comorbidities

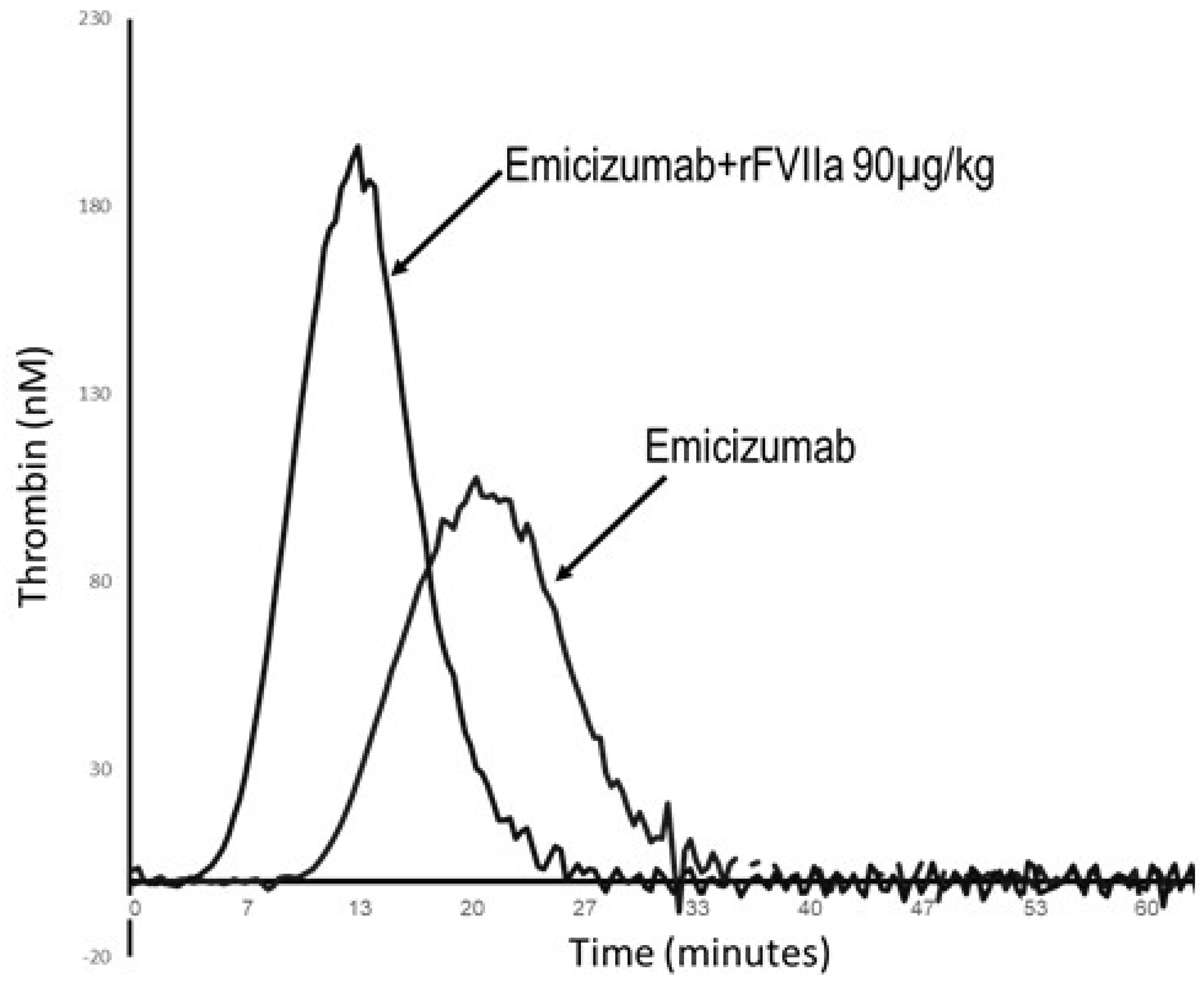

3. Novel Therapies: Emerging Complications of Thrombosis and Thrombotic Microangiopathy

4. Novel Anticoagulant Drug Targets: Exploring the Role of FXI in Rebalancing Hemostasis

5. Summary and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mannucci, P.M.; Franchini, M. Mechanism of hemostasis defects and management of bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 21, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, H.H.; McCarty, O.J.T.; Favaloro, E.J. Contact Activation: Where Thrombosis and Hemostasis Meet on a Foreign Surface, Plus a Mini-editorial Compilation (“Part XVI”). Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2024, 50, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, H.; Shiraki, K.; Shimpo, H.; Miyata, T. Evaluation of Deficiency and Excessive Condition of Thrombin Burst Using Laboratory Tests. Thromb. Haemost. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.; Sánchez-Vega, B.; Wu, S.M.; Lanir, N.; Stafford, D.W.; Solera, J. A missense mutation in gamma-glutamyl carboxylase gene causes combined deficiency of all vitamin K-dependent blood coagulation factors. Blood 1998, 92, 4554–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Jin, D.Y.; Stafford, D.W.; Tie, J.K. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of coagulation factors: Insights from a cell-based functional study. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, J.; Watzka, M.; Rost, S.; Müller, C.R. VKORC1: Molecular target of coumarins. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, P.; Carcao, M.; Kenet, G.; Pipe, S.W. Haemophilia. Lancet 2025, 405, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.; Benson, G.; Evans, G.; Harrison, C.; Mangles, S.; Makris, M. Cardiovascular disease in hereditary haemophilia: The challenges of longevity. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 197, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soucie, J.M.; Nuss, R.; Evatt, B.; Abdelhak, A.; Cowan, L.; Hill, H.; Kolakoski, M.; Wilber, N. Mortality among males with hemophilia: Relations with source of medical care. The Hemophilia Surveillance System Project Investigators. Blood 2000, 96, 437–442. [Google Scholar]

- Makris, M.; Lassila, R.; Kennedy, M. Challenges in ageing persons with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2024, 30, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Huang, D.; Jiang, Y. A real-world pharmacovigilance analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system database for emicizumab. Thromb. Res. 2025, 254, 109422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, M.J.; Hsue, P.Y.; Benjamin, L.A.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Currier, J.S.; Freiberg, M.S.; Grinspoon, S.K.; Levin, J.; Longenecker, C.T.; Post, W.S. Characteristics, Prevention, and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 140, e98–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.V.; Joseph, S.B.; Dittmer, D.P.; Mackman, N. Cardiovascular Disease and Thrombosis in HIV Infection. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Evans, P.C.; Strijdom, H.; Xu, S. HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy and vascular dysfunction: Effects, mechanisms and treatments. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 217, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horberg, M.; Thompson, M.; Agwu, A.; Colasanti, J.; Haddad, M.; Jain, M.; McComsey, G.; Radix, A.; Rakhmanina, N.; Short, W.R.; et al. Primary Care Guidance for Providers of Care for Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2024 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae479, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipp, C. The aging patient with hemophilia: Complications, comorbidities, and management issues. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2010, 2010, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badescu, M.C.; Badulescu, O.V.; Butnariu, L.I.; Floria, M.; Ciocoiu, M.; Costache, I.I.; Popescu, D.; Bratoiu, I.; Buliga-Finis, O.N.; Rezus, C. Current Therapeutic Approach to Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Congenital Hemophilia. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, M.; Focosi, D.; Mannucci, P.M. How we manage cardiovascular disease in patients with hemophilia. Haematologica 2023, 108, 1748–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atar, D.; Vandenbriele, C.; Agewall, S.; Gigante, B.; Goette, A.; Gorog, D.A.; Holme, P.A.; Krychtiuk, K.A.; Rocca, B.; Siller-Matula, J.M.; et al. Management of patients with congenital bleeding disorders and cardiac indications for antithrombotic therapy. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2025, 11, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. and Peer Review Committee Members. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1–e156, Erratum in Circulation 2024, 149, e167. Erratum in Circulation 2024, 149, e936. Erratum in Circulation 2024, 149, e1413.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, P.M. Management of antithrombotic therapy for acute coronary syndromes and atrial fibrillation in patients with hemophilia. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, S. Acute coronary syndrome management in hemophiliacs: How to maintain balance?: A review. Medicine 2023, 102, e33298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alblaihed, L.; Dubbs, S.B.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Hemophilia emergencies. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 56, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehnel, C.; Rickli, H.; Graf, L.; Maeder, M.T. Coronary angiography with or without percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with hemophilia-Systematic review. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, M.; Tagliaferri, A.; Mannucci, P.M. The management of hemophilia in elderly patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2007, 2, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badulescu, O.V.; Scripcariu, D.V.; Badescu, M.C.; Ciocoiu, M.; Vladeanu, M.C.; Plesoianu, C.E.; Bojan, A.; Iliescu-Halitchi, D.; Tudor, R.; Huzum, B.; et al. Debates Surrounding the Use of Antithrombotic Therapy in Hemophilic Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: Best Strategies to Minimize Severe Bleeding Risk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.; Lassila, R.; Bekdache, C.; Owaidah, T.; Sholzberg, M. Use of antithrombotic therapy in patients with hemophilia: A selected synopsis of the European Hematology Association—International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis—European Association for Hemophilia and Allied Disorders—European Stroke Organization Clinical Practice Guidance document. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2025, 23, 745–749. [Google Scholar]

- Vadalà, G.; Mingoia, G.; Astuti, G.; Madaudo, C.; Sucato, V.; Adorno, D.; D’Agostino, A.; Novo, G.; Corrado, E.; Galassi, A.R. Coronary Revascularization in Patients with Hemophilia and Acute Coronary Syndrome: Case Report and Brief Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, O.; Levy-Mendelovich, S.; Budnik, I.; Ludan, N.; Lyskov, S.K.; Livnat, T.; Avishai, E.; Efros, O.; Lubetsky, A.; Lalezari, S.; et al. Management of surgery in persons with hemophilia A receiving emicizumab prophylaxis: Data from a national hemophilia treatment center. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 7, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, M.U.; Negrier, C.; Paz-Priel, I.; Chang, T.; Chebon, S.; Lehle, M.; Mahlangu, J.; Young, G.; Kruse-Jarres, R.; Mancuso, M.E.; et al. Long-term outcomes with emicizumab prophylaxis for hemophilia A with or without FVIII inhibitors from the HAVEN 1-4 studies. Blood 2021, 137, 2231–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misgav, M.; Brutman-Barazani, T.; Budnik, I.; Avishai, E.; Schapiro, J.; Bashari, D.; Barg, A.A.; Lubetsky, A.; Livnat, T.; Kenet, G. Emicizumab prophylaxis in haemophilia patients older than 50 years with cardiovascular risk factors: Real-world data. Haemophilia 2021, 27, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbattista, M.; Ciavarella, A.; Noone, D.; Peyvandi, F. Hemorrhagic and thrombotic adverse events associated with emicizumab and extended half-life factor VIII replacement drugs: EudraVigilance data of 2021. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thillo, Q.; Hermans, C. Rebalancing agents in hemophilia: Knowns, unknowns, and uncertainties. Haematologica 2025, 110, 2902–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, D.E.; Nichols, T.C.; Merricks, E.; Bellinger, D.A.; Herzog, R.W.; Monahan, P.E. Animal models of hemophilia. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2012, 105, 151–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, A.; Barros, S.; Ivanciu, L.; Cooley, B.; Qin, J.; Racie, T.; Hettinger, J.; Carioto, M.; Jiang, Y.; Brodsky, J.; et al. An RNAi therapeutic targeting antithrombin to rebalance the coagulation system and promote hemostasis in hemophilia. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenet, G.; Nolan, B.; Zulfikar, B.; Antmen, B.; Kampmann, P.; Matsushita, T.; You, C.W.; Vilchevska, K.; Bagot, C.N.; Sharif, A.; et al. Fitusiran prophylaxis in people with hemophilia A or B who switched from prior BPA/CFC prophylaxis: The ATLAS-PPX trial. Blood 2024, 143, 2256–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.; Kavakli, K.; Klamroth, R.; Matsushita, T.; Peyvandi, F.; Pipe, S.W.; Rangarajan, S.; Shen, M.C.; Srivastava, A.; Sun, J.; et al. Safety and efficacy of a fitusiran antithrombin-based dose regimen in people with hemophilia A or B: The ATLAS-OLE study. Blood 2025, 145, 2966–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Dou, F.; Gao, J. Fitusiran: The first approved siRNA therapy for hemophilia via reducing plasma antithrombin levels. Drug Discov. Ther. 2025, 19, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, P. Anti-tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) therapy: A novel approach to the treatment of haemophilia. Int. J. Hematol. 2020, 111, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlangu, J.N. Progress in the Development of Anti-tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitors for Haemophilia Management. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 670526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, T.; Shapiro, A.; Abraham, A.; Angchaisuksiri, P.; Castaman, G.; Cepo, K.; d’Oiron, R.; Frei-Jones, M.; Goh, A.S.; Haaning, J.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of Concizumab in Hemophilia with Inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matino, D.; Palladino, A.; Taylor, C.T.; Hwang, E.; Raje, S.; Nayak, S.; McDonald, R.; Acharya, S.S.; Mahlangu, J.; Jiménez-Yuste, V.; et al. Marstacimab prophylaxis in hemophilia A/B without inhibitors: Results from the phase 3 BASIS trial. Blood 2025, 146, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. FDA approves first anti-TFPI antibody for haemophilia A and B. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magisetty, J.; Kondreddy, V.; Keshava, S.; Das, K.; Esmon, C.T.; Pendurthi, U.R.; Rao, L.V.M. Selective inhibition of activated protein C anticoagulant activity protects against hemophilic arthropathy in mice. Blood 2022, 139, 2830–2841, Erratum in Blood 2024, 144, 588. Erratum for Blood 2022, 139, 2830–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Han, J.; Yi, J.; Zuo, B.; Huang, L.; Ma, Z.; Li, T.; et al. Safety and efficacy of an anti-human APC antibody for prophylaxis of congenital factor deficiencies in preclinical models. Blood 2023, 142, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, R.; Bologna, L.; Manetti, M.; Melchiorre, D.; Rosa, I.; Dewarrat, N.; Suardi, S.; Amini, P.; Fernández, J.A.; Burnier, L.; et al. Targeting anticoagulant protein S to improve hemostasis in hemophilia. Blood 2018, 131, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barg, A.A.; Brutman-Barazani, T.; Avishai, E.; Budnik, I.; Cohen, O.; Dardik, R.; Levy-Mendelovich, S.; Livnat, T.; Kenet, G. Anti-TFPI for hemostasis induction in patients with rare bleeding disorders, an ex vivo thrombin generation (TG) guided pilot study. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2022, 95, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalbert, L.R.; Rosen, E.D.; Moons, L.; Chan, J.C.; Carmeliet, P.; Collen, D.; Castellino, F.J. Inactivation of the gene for anticoagulant protein C causes lethal perinatal consumptive coagulopathy in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy-Mendelovich, S.; Avishai, E.; Samelson-Jones, B.J.; Dardik, R.; Brutman-Barazani, T.; Nisgav, Y.; Livnat, T.; Kenet, G. A Novel Murine Model Enabling rAAV8-PC Gene Therapy for Severe Protein C Deficiency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barg, A.A.; Livnat, T.; Kenet, G. Factor XI deficiency: Phenotypic age-related considerations and clinical approach towards bleeding risk assessment. Blood 2024, 143, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, O.; Santagata, D.; Ageno, W. Novel horizons in anticoagulation: The emerging role of factor XI inhibitors across different settings. Haematologica 2024, 109, 3110–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenburgh, J.C.; Weitz, J.I. News at XI: Moving beyond factor Xa inhibitors. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gailani, D.; Gruber, A. Targeting factor XI and factor XIa to prevent thrombosis. Blood 2024, 143, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannucci, P.M. Hemophilia treatment innovation: 50 years of progress and more to come. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Therapy/Agent | Mechanism | Potential Risk | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bypass agents | Thrombosis, DIC | Excess factor activation | Monitor thrombotic markers, use with caution in elderly inhibitor patients with cardiovascular risk factors |

| Emicizumab | Thrombosis, TMA | Overactivation of thrombin generation | Requires vigilance with aPCC co-administration |

| Rebalancing agents | Potential off-target effects | Alteration of coagulation balance | Limited real-world clinical experience, thrombosis reported in/after clinical trials, caution is advised in patients with risk factors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kenet, G.; Levy-Mendelovich, S.; Livnat, T.; Brenner, B. Challenges in Balancing Hemostasis and Thrombosis in Therapy Tailoring for Hemophilia: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031373

Kenet G, Levy-Mendelovich S, Livnat T, Brenner B. Challenges in Balancing Hemostasis and Thrombosis in Therapy Tailoring for Hemophilia: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031373

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenet, Gili, Sarina Levy-Mendelovich, Tami Livnat, and Benjamin Brenner. 2026. "Challenges in Balancing Hemostasis and Thrombosis in Therapy Tailoring for Hemophilia: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031373

APA StyleKenet, G., Levy-Mendelovich, S., Livnat, T., & Brenner, B. (2026). Challenges in Balancing Hemostasis and Thrombosis in Therapy Tailoring for Hemophilia: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031373