Neurochemical and Energetic Alterations in Depression: A Narrative Review of Potential PET Biomarkers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. PET Findings

3.1. PET Alterations

3.1.1. Glucose PET Alterations

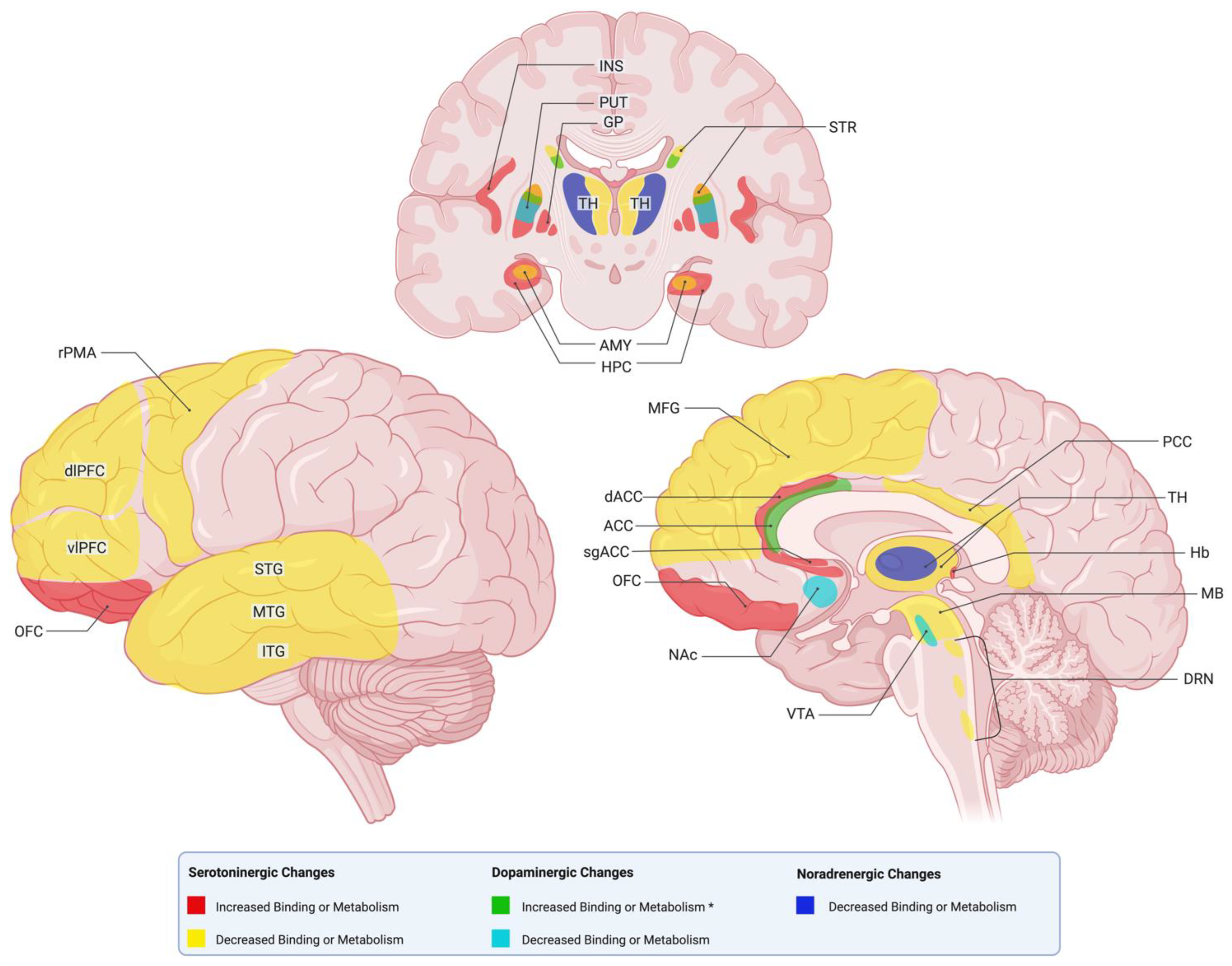

3.1.2. Serotonin PET Alterations

3.1.3. Dopamine PET Alterations

3.1.4. Norepinephrine PET Alterations

3.1.5. Monoamine Oxidase (MAO) PET Alterations

3.1.6. Other PET Alterations

3.2. Inflammation State Findings and Cerebral Blood Flow

3.3. Other Notable Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Integrative Interpretation of Metabolic, Neurochemical, Inflammatory, and Perfusion PET Findings in Depression

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baeken, C.; De Raedt, R.; Bossuyt, A. Is Treatment-Resistance in Unipolar Melancholic Depression Characterized by Decreased Serotonin 2A Receptors in the Dorsal Prefrontal—Anterior Cingulate Cortex? Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, B.R.; Browning, M.; Norbury, R.; Igoumenou, A.; Cowen, P.J.; Harmer, C.J. Predicting Treatment Response in Depression: The Role of Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 21, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kito, S.; Fujita, K.; Koga, Y. Regional Cerebral Blood Flow Changes after Low-Frequency Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuropsychobiology 2008, 58, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.T.; Hsieh, J.C.; Huang, H.H.; Chen, M.H.; Juan, C.H.; Tu, P.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Wang, S.J.; Cheng, C.M.; Su, T.P. Cognition-Modulated Frontal Activity in Prediction and Augmentation of Antidepressant Efficacy: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konarski, J.Z.; Kennedy, S.H.; Segal, Z.V.; Lau, M.A.; Bieling, P.J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Mayberg, H.S. Predictors of Nonresponse to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy or Venlafaxine Using Glucose Metabolism in Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009, 34, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Kuwabara, H.; Gould, N.F.; Nassery, N.; Savonenko, A.; Joo, J.H.; Bigos, K.L.; Kraut, M.; Brasic, J.; Holt, D.P.; et al. Molecular Imaging of the Serotonin Transporter Availability and Occupancy by Antidepressant Treatment in Late-Life Depression. Neuropharmacology 2021, 194, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Kenneth Evans, F.R.; Krüger, S.; Mayberg, H.S.; Jeffrey Meyer, F.H.; Sonia McCann, F.; Arifuzzman, A.I.; Sylvain Houle, B.; Vaccarino, F.J. Changes in Regional Brain Glucose Metabolism Measured with Positron Emission Tomography After Paroxetine Treatment of Major Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Konarski, J.Z.; Segal, Z.V.; Lau, M.A.; Bieling, P.J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Mayberg, H.S. Article Differences in Brain Glucose Metabolism Between Responders to CBT and Venlafaxine in a 16-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, A.L.; Saxena, S.; Stoessel, P.; Gillies, L.A.; Fairbanks, L.A.; Alborzian, S.; Phelps, M.E.; Huang, S.-C.; Wu, H.-M.; Ho, M.L.; et al. Regional Brain Metabolic Changes in Patients with Major Depression Treated with Either Paroxetine or Interpersonal Therapy Preliminary Findings. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drevets, W.C.; Bogers, W.; Raichle, M.E. F Unctional Anatomical Correlates of Antidepressant Drug Treatment Assessed Using PET Measures of Regional Glucose Metabolism. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 12, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heeringen, K.; Wu, G.R.; Vervaet, M.; Vanderhasselt, M.A.; Baeken, C. Decreased Resting State Metabolic Activity in Frontopolar and Parietal Brain Regions Is Associated with Suicide Plans in Depressed Individuals. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 84, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Baker, S.C.; Rogers, R.D.; O’leary, D.A.; Paykel, E.S.; Frith, C.D.; Dolan, R.J.; Sahakian, B.J. Prefrontal Dysfunction in Depressed Patients Performing a Complex Planning Task: A Study Using Positron Emission Tomography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S.; Chadda, R.K.; Kumar, N.; Bal, C.S. Brain SPECT Guided Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (RTMS) in Treatment Resistant Major Depressive Disorder. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2016, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milak, M.S.; Parsey, R.V.; Lee, L.; Oquendo, M.A.; Olvet, D.M.; Eipper, F.; Malone, K.; Mann, J.J. Pretreatment Regional Brain Glucose Uptake in the Midbrain on PET May Predict Remission from a Major Depressive Episode after Three Months of Treatment. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2009, 173, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marano, C.M.; Workman, C.I.; Kramer, E.; Hermann, C.R.; Ma, Y.; Dhawan, V.; Chaly, T.; Eidelberg, D.; Smith, G.S. Longitudinal Studies of Cerebral Glucose Metabolism in Late-Life Depression and Normal Aging. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Kramer, E.; Hermann, C.R.; Goldberg, S.; Ma, Y.; Dhawan, V.; Barnes, A.; Chaly, T.; Belakhleff, A.; Laghrissi-Thode, F.; et al. Acute and Chronic Effects of Citalopram on Cerebral Glucose Metabolism in Geriatric Depression. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 10, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zobel, A.; Joe, A.; Freymann, N.; Clusmann, H.; Schramm, J.; Reinhardt, M.; Biersack, H.J.; Maier, W.; Broich, K. Changes in Regional Cerebral Blood Flow by Therapeutic Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Depression: An Exploratory Approach. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2005, 139, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasile, R.G.; Schwartzb, R.B.; Garadab, B.; Holmanb, B.L.; Alperta, M.; Davidsona, P.B.; Schildkraut, J.J. Focal Cerebral Perfusion Defects Demonstrated by 99mTc-Hexamethylpropyleneamine Oxime SPECT in Elderly Depressed Patients. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 1996, 67, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Teneback, C.C.; Ziad Nahas, B.; Speer, A.M.; Molloy, M.; Laurie Stallings, R.E.; Kenneth Spicer, P.M.; Craig Risch, S.; George, M.S. REGULAR ARTICLES Changes in Prefrontal Cortex and Paralimbic Activity in Depression Following Two Weeks of Daily Left Prefrontal TMS. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffman, J.L.; Witte, J.M.; Tanner, A.S.; Ghaznavi, S.; Abernethy, R.S.; Crain, L.D.; Giulino, P.U.; Lable, I.; Levy, R.A.; Dougherty, D.D.; et al. Neural Predictors of Successful Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Persistent Depression. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.H.Y.; Reed, L.J.; Meyer, J.H.; Kennedy, S.; Houle, S.; Eisfeld, B.S.; Brown, G.M. Noradrenergic Dysfunction in the Prefrontal Cortex in Depression: An [15O] H2O PET Study of the Neuromodulatory Effects of Clonidine. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Keith Lloyd, M.R.; Jones, I.K.; Barnes, A.; Pilowsky, L.S. Changes in Regional Cerebral Blood Flow with Venlafaxine in the Treatment of Major Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, J.; Karlsson, H.; Kajander, J.; Lepola, A.; Markkula, J.; Rasi-Hakala, H.; Någren, K.; Salminen, J.K.; Hietala, J. Decreased Brain Serotonin 5-HT1A Receptor Availability in Medication-Naive Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: An in-Vivo Imaging Study Using PET and [Carbonyl-11C]WAY-100635. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Oquendo, M.A.; Milak, M.; Miller, J.M.; Burke, A.; Ogden, R.T.; Parsey, R.V.; Mann, J.J. Positron Emission Tomography Quantification of Serotonin1A Receptor Binding in Suicide Attempters with Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeken, C.; De Raedt, R.; Bossuyt, A.; Van Hove, C.; Mertens, J.; Dobbeleir, A.; Blanckaert, P.; Goethals, I. The Impact of HF-RTMS Treatment on Serotonin2A Receptors in Unipolar Melancholic Depression. Brain Stimul. 2011, 4, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinot, M.L.P.; Martinot, J.L.; Ringuenet, D.; Galinowski, A.; Gallarda, T.; Bellivier, F.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Lemaitre, H.; Artiges, E. Baseline Brain Metabolism in Resistant Depression and Response to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 2710–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lothe, A.; Saoud, M.; Bouvard, S.; Redouté, J.Ô.; Lerond, J.Ô.; Ryvlin, P. 5-HT1A Receptor Binding Changes in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder before and after Antidepressant Treatment: A Pilot [18F]MPPF Positron Emission Tomography Study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2012, 203, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.W.; Ho, P.S.; Kuo, S.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Liang, C.S.; Yen, C.H.; Huang, C.C.; Ma, K.H.; Shiue, C.Y.; Huang, W.S.; et al. Disproportionate Reduction of Serotonin Transporter May Predict the Response and Adherence to Antidepressants in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Positron Emission Tomography Study with 4-[18F]-ADAM. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 18, pyu120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.C.; Lin, S.H.; Chen, P.S.; Chang, H.H.; Lee, I.H.; Yeh, T.L.; Chen, K.C.; Chiu, N.T.; Yao, W.J.; Liao, M.H.; et al. Quantifying Midbrain Serotonin Transporter in Depression: A Preliminary Study of Diagnosis and Naturalistic Treatment Outcome. Pharmacopsychiatry 2015, 48, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzenberger, R.; Kranz, G.S.; Haeusler, D.; Akimova, E.; Savli, M.; Hahn, A.; Mitterhauser, M.; Spindelegger, C.; Philippe, C.; Fink, M.; et al. Prediction of SSRI Treatment Response in Major Depression Based on Serotonin Transporter Interplay between Median Raphe Nucleus and Projection Areas. Neuroimage 2012, 63, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.H.; Kapur, S.; Eisfeld, B.; Brown, G.M.; Houle, S.; DaSilva, J.; Wilson, A.A.; Rafi-Tari, S.; Mayberg, H.S.; Kennedy, S.H. Article The Effect of Paroxetine on 5-HT 2A Receptors in Depression: An [18F]Setoperone PET Imaging Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubol, M.; Trichard, C.; Leroy, C.; Granger, B.; Tzavara, E.T.; Martinot, J.L.; Artiges, E. Lower Midbrain Dopamine Transporter Availability in Depressed Patients: Report from High-Resolution PET Imaging. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 262, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzagalli, D.A.; Berretta, S.; Wooten, D.; Goer, F.; Pilobello, K.T.; Kumar, P.; Murray, L.; Beltzer, M.; Boyer-Boiteau, A.; Alpert, N.; et al. Assessment of Striatal Dopamine Transporter Binding in Individuals with Major Depressive Disorder: In Vivo Positron Emission Tomography and Postmortem Evidence. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.K.; Yeh, T.L.; Yao, W.J.; Lee, I.H.; Chen, P.S.; Chiu, N.T.; Lu, R.B. Greater Availability of Dopamine Transporters in Patients with Major Depression—A Dual-Isotope SPECT Study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2008, 162, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larisch, R.; Klimke, A.; Vosberg, H.; Löffler, S.; Gaebel, W.; Mü Ller-Gä Rtner, H.-W. In Vivo Evidence for the Involvement of Dopamine-D 2 Receptors in Striatum and Anterior Cingulate Gyrus in Major Depression 1. NeuroImage 1997, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Árgyelán, M.; Szabó, Z.; Kanyó, B.; Tanács, A.; Kovács, Z.; Janka, Z.; Pávics, L. Dopamine Transporter Availability in Medication Free and in Bupropion Treated Depression: A 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 89, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, S.; Yamada, M.; Takano, H.; Nagashima, T.; Takahata, K.; Yokokawa, K.; Ito, T.; Ishii, T.; Kimura, Y.; Zhang, M.R.; et al. Norepinephrine Transporter in Major Depressive Disorder: A PET Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, R.; Stenkrona, P.; Takano, A.; Svensson, J.; Andersson, M.; Nag, S.; Asami, Y.; Hirano, Y.; Halldin, C.; Lundberg, J. Venlafaxine ER Blocks the Norepinephrine Transporter in the Brain of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A PET Study Using [18F]FMeNER-D2. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 22, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, H.; Arakawa, R.; Nogami, T.; Suzuki, M.; Nagashima, T.; Fujiwara, H.; Kimura, Y.; Kodaka, F.; Takahata, K.; Shimada, H.; et al. Norepinephrine Transporter Occupancy by Nortriptyline in Patients with Depression: A Positron Emission Tomography Study with (S,S)-[18F]FMeNER-D2. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 17, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiuccariello, L.; Houle, S.; Miler, L.; Cooke, R.G.; Rusjan, P.M.; Rajkowska, G.; Levitan, R.D.; Kish, S.J.; Kolla, N.J.; Ou, X.; et al. Elevated Monoamine Oxidase A Binding during Major Depressive Episodes Is Associated with Greater Severity and Reversed Neurovegetative Symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.H.; Ginovart, N.; Boovariwala, A.; Sagrati, S.; Hussey, D.; Garcia, A.; Young, T.; Praschak-Rieder, N.; Wilson, A.A.; Houle, S. Elevated Monoamine Oxidase A Levels in the Brain An Explanation for the Monoamine Imbalance of Major Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moriguchi, S.; Wilson, A.A.; Miler, L.; Rusjan, P.M.; Vasdev, N.; Kish, S.J.; Rajkowska, G.; Wang, J.; Bagby, M.; Mizrahi, R.; et al. Monoamine Oxidase b Total Distribution Volume in the Prefrontal Cortex of Major Depressive Disorder: An 11csl25.1188 Positron Emission Tomography Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, J.; Houle, S.; Parkes, J.; Rusjan, P.; Sagrati, S.; Wilson, A.A.; Meyer, J.H. Monoamine Oxidase a Inhibitor Occupancy during Treatment of Major Depressive Episodes with Moclobemide or St. John’s Wort: An [11C]-Harmine PET Study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011, 36, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldinger-Melich, P.; Gryglewski, G.; Philippe, C.; James, G.M.; Vraka, C.; Silberbauer, L.; Balber, T.; Vanicek, T.; Pichler, V.; Unterholzner, J.; et al. The Effect of Electroconvulsive Therapy on Cerebral Monoamine Oxidase A Expression in Treatment-Resistant Depression Investigated Using Positron Emission Tomography. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, K.; Yttredahl, A.; Oquendo, M.A.; Mann, J.J.; Hillmer, A.T.; Carson, R.E.; Miller, J.M. Data-Driven Analysis of Kappa Opioid Receptor Binding in Major Depressive Disorder Measured by Positron Emission Tomography. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Kramer, E.; Ma, Y.; Kingsley, P.; Dhawan, V.; Chaly, T.; Eidelberg, D. The Functional Neuroanatomy of Geriatric Depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M.; Fukudo, S.; Tashiro, A.; Utsumi, A.; Tamura, D.; Itoh, M.; Iwata, R.; Tashiro, M.; Mochizuki, H.; Funaki, Y.; et al. Decreased Histamine H1 Receptor Binding in the Brain of Depressed Patients. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 20, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, E.; Wilson, A.A.; Mizrahi, R.; Rusjan, P.M.; Miler, L.; Rajkowska, G.; Suridjan, I.; Kennedy, J.L.; Rekkas, P.V.; Houle, S.; et al. Role of Translocator Protein Density, a Marker of Neuroinflammation, in the Brain during Major Depressive Episodes. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holthoff, V.A.; Beuthien-Baumann, B.; Zündorf, G.; Triemer, A.; Lüdecke, S.; Winiecki, P.; Koch, R.; Füchtner, F.; Herholz, K. Changes in Brain Metabolism Associated with Remission in Unipolar Major Depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 110, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottaghy, F.M.; Keller, C.E.; Gangitano, M.; Ly, J.; Thall, M.; Anthony Parker, J.; Pascual-Leone, A. Correlation of Cerebral Blood Flow and Treatment Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Depressed Patients. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2002, 115, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, Z.; Teneback, C.C.; Andy Kozel, B.; Speer, A.M.; DeBrux, C.; Molloy, M.; Laurie Stallings, M.; Kenneth Spicer, P.M.; Arana, G.; Bohning, D.E.; et al. Brain Effects of TMS Delivered Over Prefrontal Cortex in Depressed Adults: Role of Stimulation Frequency and Coil-Cortex Distance. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001, 13, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.M.; Mayberg, H.S.; Giacobbe, P.; Hamani, C.; Craddock, R.C.; Kennedy, S.H. Subcallosal Cingulate Gyrus Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 64, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, C.K.; Sachdev, P.S.; Haindl, W.; Wen, W.; Mitchell, P.B.; Croker, V.M.; Malhi, G.S. High (15 Hz) and Low (1 Hz) Frequency Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Have Different Acute Effects on Regional Cerebral Blood Flow in Depressed Patients. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, E.; Attwells, S.; Wilson, A.A.; Mizrahi, R.; Rusjan, P.M.; Miler, L.; Xu, C.; Sharma, S.; Kish, S.; Houle, S.; et al. Association of Translocator Protein Total Distribution Volume with Duration of Untreated Major Depressive Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, O.L.; Willemsen, A.T.M.; Roosink, M.; Bartels, A.L.; Harry Hendrikse, N.; Bosker, F.J.; Den Boer, J.A. Locally Increased P-Glycoprotein Function in Major Depression: A PET Study with [11C]Verapamil as a Probe for P-Glycoprotein Function in the Bloodbrain Barrier. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 12, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.J. Relationship of Neurotransmitters to the Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Munoz, F.; Alamo, C. Monoaminergic Neurotransmission: The History of the Discovery of Antidepressants from 1950s Until Today. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 1563–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Caballero, L.; Torres-Sanchez, S.; Romero-López-Alberca, C.; González-Saiz, F.; Mico, J.A.; Berrocoso, E. Monoaminergic System and Depression. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 377, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drevets, W.C. Neuroimaging and Neuropathological Studies of Depression: Implications for the Cognitive-Emotional Features of Mood Disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001, 11, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzagalli, D.A.; Roberts, A.C. Prefrontal Cortex and Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.; Zhang, J. Neuroinflammation, Memory, and Depression: New Approaches to Hippocampal Neurogenesis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacková, L.; Jáni, M.; Brázdil, M.; Nikolova, Y.S.; Marečková, K. Cognitive Impairment and Depression: Meta-Analysis of Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Neuroimage Clin. 2021, 32, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, M.B. Monoamine Oxidase. Its Inhibition. Mod. Probl. Pharmacopsychiatry 1975, 10, 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.M.; Baldinger-Melich, P.; Philippe, C.; Kranz, G.S.; Vanicek, T.; Hahn, A.; Gryglewski, G.; Hienert, M.; Spies, M.; Traub-Weidinger, T.; et al. Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors on Interregional Relation of Serotonin Transporter Availability in Major Depression. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.H.; Wilson, A.A.; Ginovart, N.; Goulding, V.; Hussey, D.; Hood, K.; Sylvain Houle, M. Occupancy of Serotonin Transporters by Paroxetine and Citalopram During Treatment of Depression: A [11C]DASB PET Imaging Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzenberger, R.; Baldinger, P.; Hahn, A.; Ungersboeck, J.; Mitterhauser, M.; Winkler, D.; Micskei, Z.; Stein, P.; Karanikas, G.; Wadsak, W.; et al. Global Decrease of Serotonin-1A Receptor Binding after Electroconvulsive Therapy in Major Depression Measured by PET. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennis, M.; Gerritsen, L.; van Dalen, M.; Williams, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Bockting, C. Prospective Biomarkers of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troubat, R.; Barone, P.; Leman, S.; Desmidt, T.; Cressant, A.; Atanasova, B.; Brizard, B.; El Hage, W.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Depression: A Review. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Xie, J.; Li, H.; Wei, H.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Meng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Cerebral Blood Flow Abnormalities in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2019, 28, 1128–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, P.A.; Kjaer, K.H.; Bench, C.J.; Rabiner, E.A.; Messa, C.; Meyer, J.; Gunn, R.N.; Grasby, P.M.; Cowen, P.J. Brain Serotonin 1A Receptor Binding Measured by Positron Emission Tomography with [11C]WAY-100635 Effects of Depression and Antidepressant Treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff-Guerrero, A.; Pellicer, F.; Mendoza-Espinosa, Y.; Martínez-Medina, P.; Romero-Romo, J.; de la Fuente-Sandoval, C. Cerebral Blood Flow Changes Associated with Experimental Pain Stimulation in Patients with Major Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 107, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, S.G.; Holligan, S.D.; Mahmud, F.H.; Cleverley, K.; Birken, C.S.; McCrindle, B.W.; Pignatiello, T.; Korczak, D.J. The Association between Depression and Physiological Markers of Glucose Homeostasis among Adolescents. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 154, 110738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, T. Glucose Metabolic Abnormality: A Crosstalk between Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2025, 23, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa-Moscoso, B.; Ullauri, C.; Chiriboga, J.D.; Silva, P.; Haro, F.; Leon-Rojas, J.E. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Bipolar Disorder: How Feasible Is This Pairing? Cureus 2022, 14, e23690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Epskamp, S.; Nesse, R.M.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Borsboom, D. What Are “good” Depression Symptoms? Comparing the Centrality of DSM and Non-DSM Symptoms of Depression in a Network Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 189, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment Modality | Glucose Alterations | Serotonin Alterations | Dopamine Alterations | Norepinephrine Alterations | MAO Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) | ↑ PFC, OFC, subgenual and anterior cingulate, insula, temporal lobe, parahippocampus, amygdala; ↓ PFC, OFC, left dlPFC, temporal lobes, left ACC, right medial temporal lobe | ↓ Right hippocampus, right dlPFC | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Deep brain stimulation (DBS) | ↑ PFC | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Vagal nerve stimulation + SSRIs | ↓ Left medial frontal gyrus, subcentral area, temporal gyri, caudate head, limbic system, brainstem | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| SSRIs (general) | ↓ Midbrain, parahippocampal gyrus, putamen, globus pallidus, ventral limbic structures, thalamus, inferior frontal gyrus, cerebellum, ACC, medial and dlPFC | ↑ Binding potential in dorsal, subgenual and pre subgenual ACC and medial orbital cortex; ↓ global serotonin binding availability | ↑ D2 receptor binding in ACC, frontal regions and striatum in responders; ↓ same regions in non-responders | Not reported | Not reported |

| Venlafaxine | ↑ Pregenual to subgenual cingulate region in non-responders; ↓ right posterior temporal gyrus and bilateral superior temporal gyri | Not reported | Not reported | ↑ NET occupancy up to 150 mg; ↓ occupancy at higher doses | Not reported |

| Paroxetine | ↑ dlPFC, vlPFC, parietal cortex, dorsal ACC; ↓ subgenual cingulate, anterior and posterior insula, hippocampus, parahippocampus, caudate, putamen, antero-inferior temporal lobe | ↓ Medial frontal gyrus, lateral OFC, temporal regions, basal ganglia, brainstem, rostral ACC, vlPFC | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sertraline | ↑ Left lateral orbital cortex, amygdala, PCC; ↓ right inferior frontal gyrus, cerebellum, ACC, medial, and dlPFC | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Citalopram/Escitalopram | ↑ Putamen, occipital cortex, cerebellum; ↓ middle frontal cortex, inferior parietal lobule | ↑ Amygdala–anterior hippocampus complex, habenula, putamen, OFC, anterior and subgenual ACC, insula, midbrain, hippocampus, globus pallidum | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Clonidine | ↓ Cerebellum, thalamus | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nortriptyline | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ↑ NET occupancy | Not reported |

| Benzodiazepines/lithium (bipolar depression) | ↓ Lateral frontal, lateral and medial temporal cortices, basal ganglia, thalamus | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) | ↑ Occipital temporal cortex, insula, temporal lobe; ↓ OFC, medial PFC | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Psychodynamic psychotherapy | ↓ Insula | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Moclobemide (MAO inhibitor) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ↓ MAO density in all brain regions |

| Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | No change in MAO distribution volume |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cornejo Schmiedl, S.J.; Astudillo Ortega, B.; Sosa-Moscoso, B.; González de Armas, G.; Montenegro Galarza, J.I.; Rodas, J.A.; Leon-Rojas, J.E. Neurochemical and Energetic Alterations in Depression: A Narrative Review of Potential PET Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031267

Cornejo Schmiedl SJ, Astudillo Ortega B, Sosa-Moscoso B, González de Armas G, Montenegro Galarza JI, Rodas JA, Leon-Rojas JE. Neurochemical and Energetic Alterations in Depression: A Narrative Review of Potential PET Biomarkers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031267

Chicago/Turabian StyleCornejo Schmiedl, Santiago Jose, Bryan Astudillo Ortega, Bernardo Sosa-Moscoso, Gabriela González de Armas, Jose Ignacio Montenegro Galarza, Jose A. Rodas, and Jose E. Leon-Rojas. 2026. "Neurochemical and Energetic Alterations in Depression: A Narrative Review of Potential PET Biomarkers" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031267

APA StyleCornejo Schmiedl, S. J., Astudillo Ortega, B., Sosa-Moscoso, B., González de Armas, G., Montenegro Galarza, J. I., Rodas, J. A., & Leon-Rojas, J. E. (2026). Neurochemical and Energetic Alterations in Depression: A Narrative Review of Potential PET Biomarkers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031267