Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis and Restoration of Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling by Diosmin Protect Against Diabetes-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

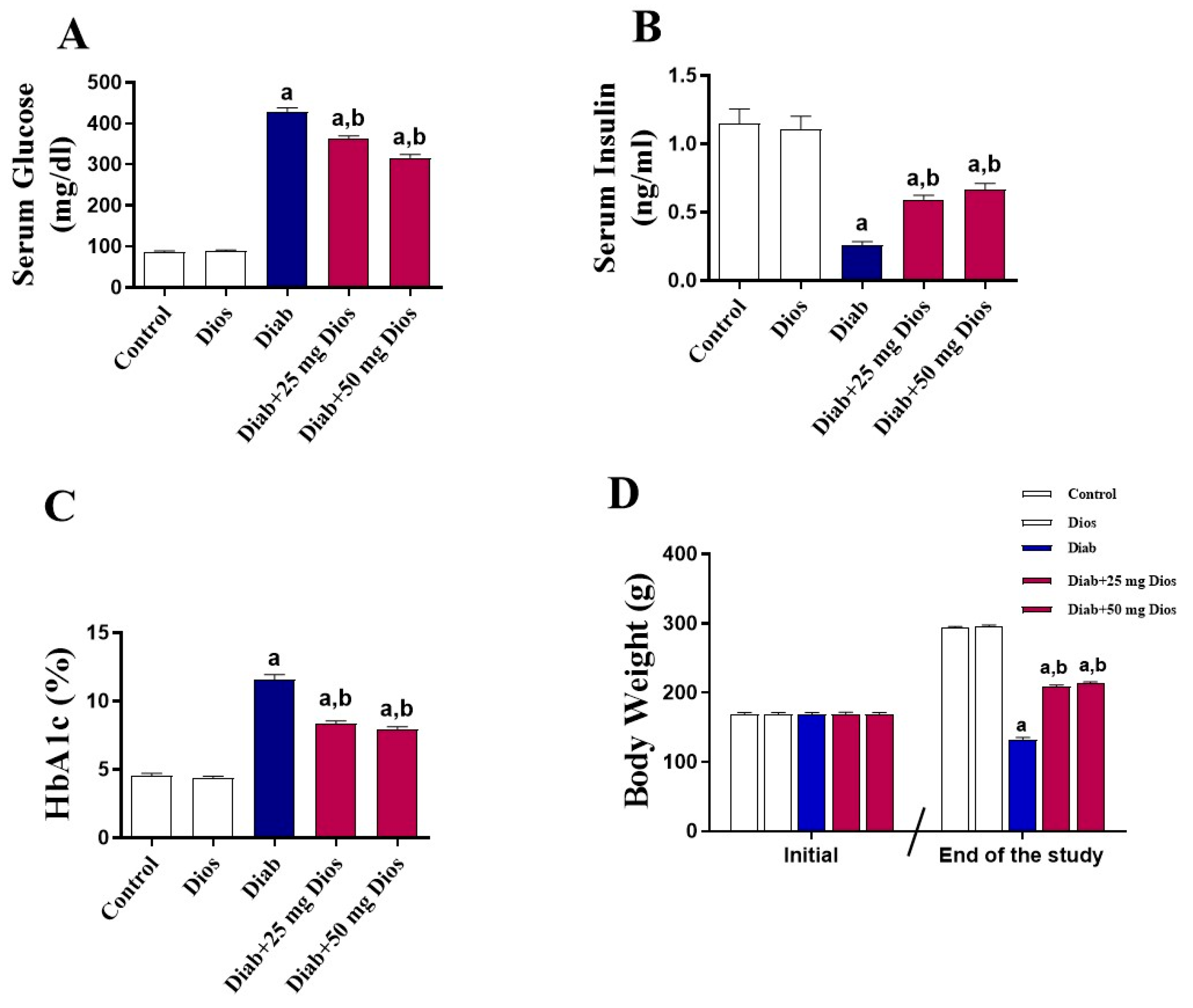

2.1. Impact of Dios on Metabolic Parameters and Body Weight in the Diabetic Rats

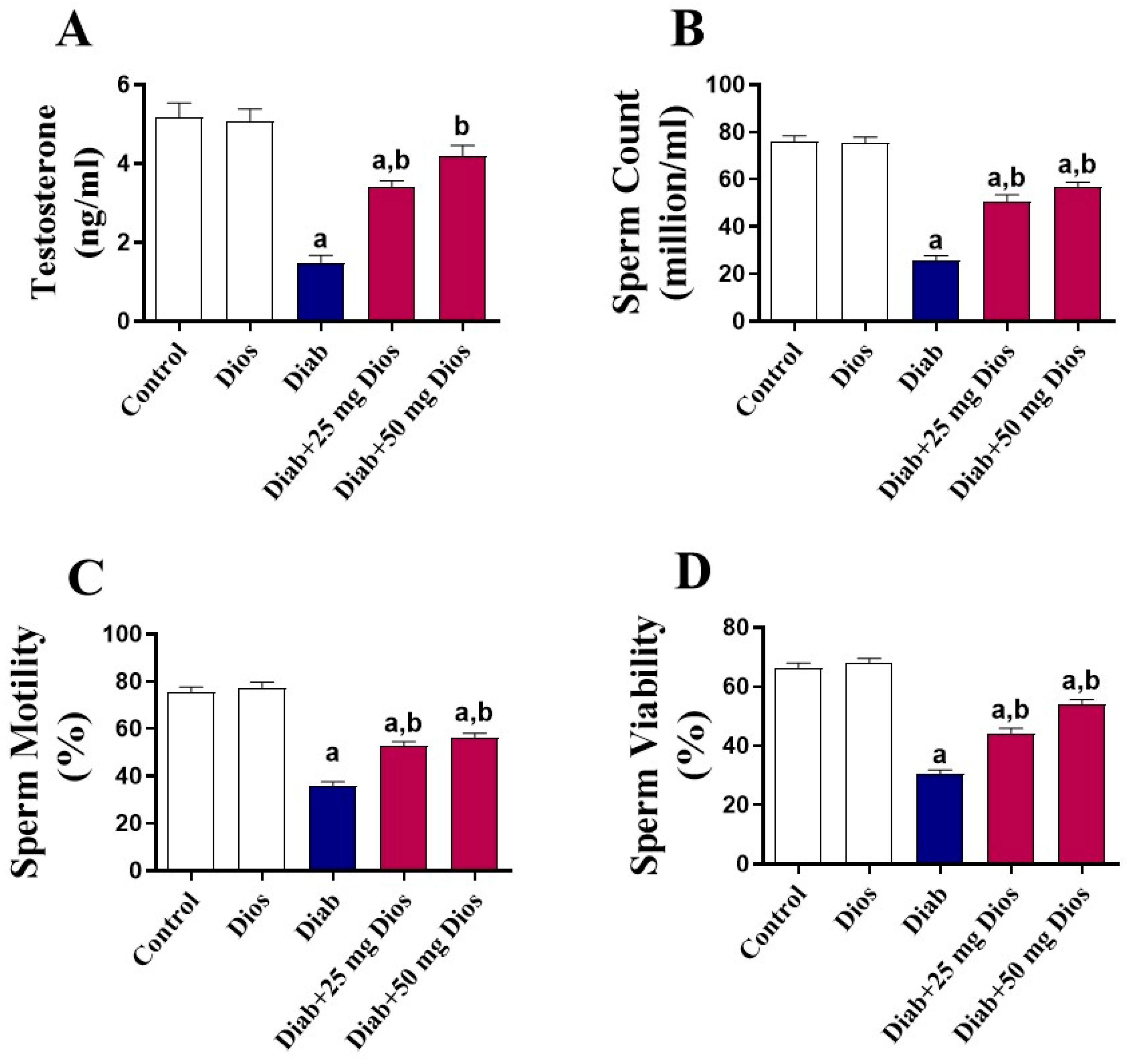

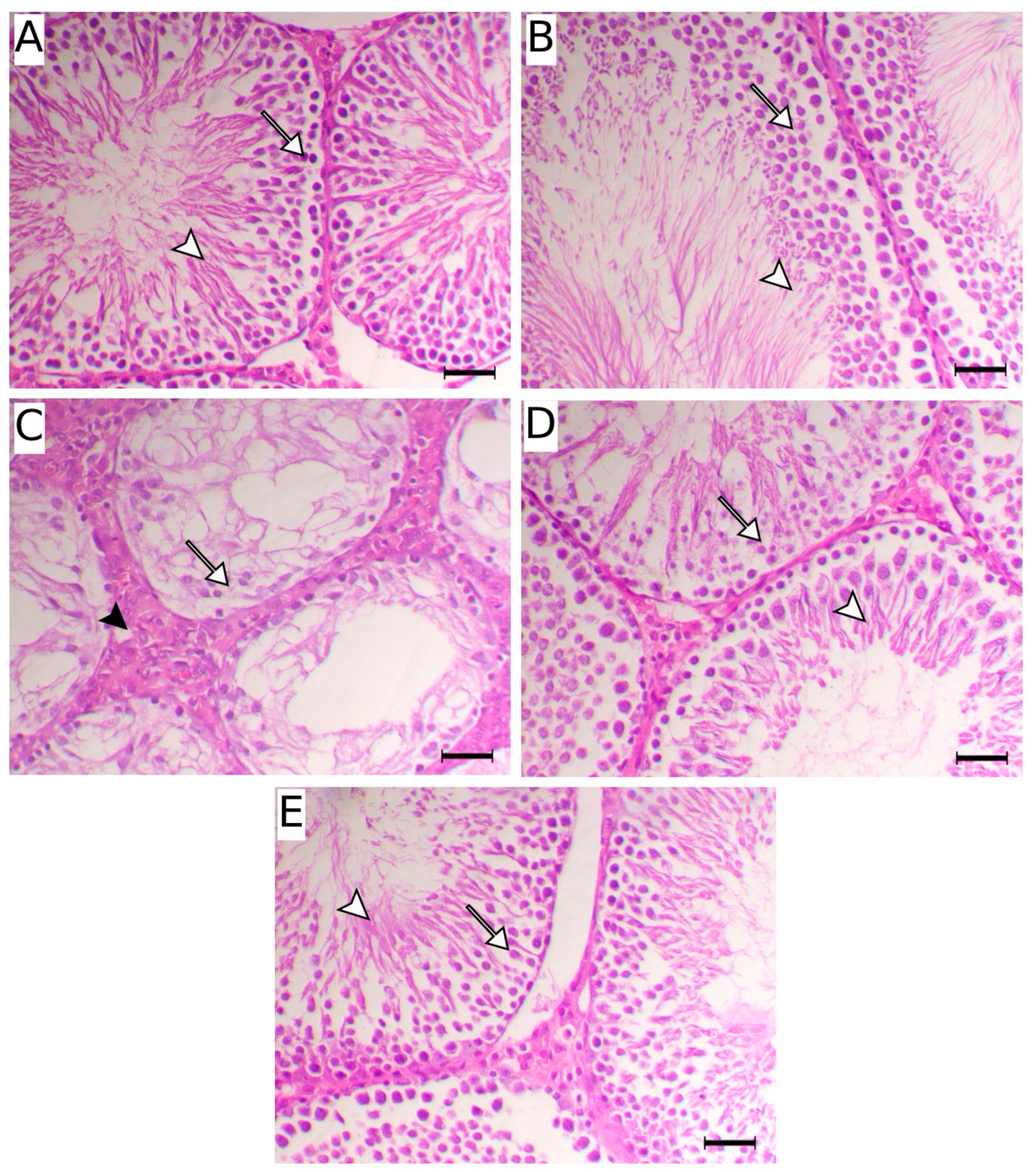

2.2. Effect of Dios on Sperm Parameters, Testosterone Levels, and Testicular Damage

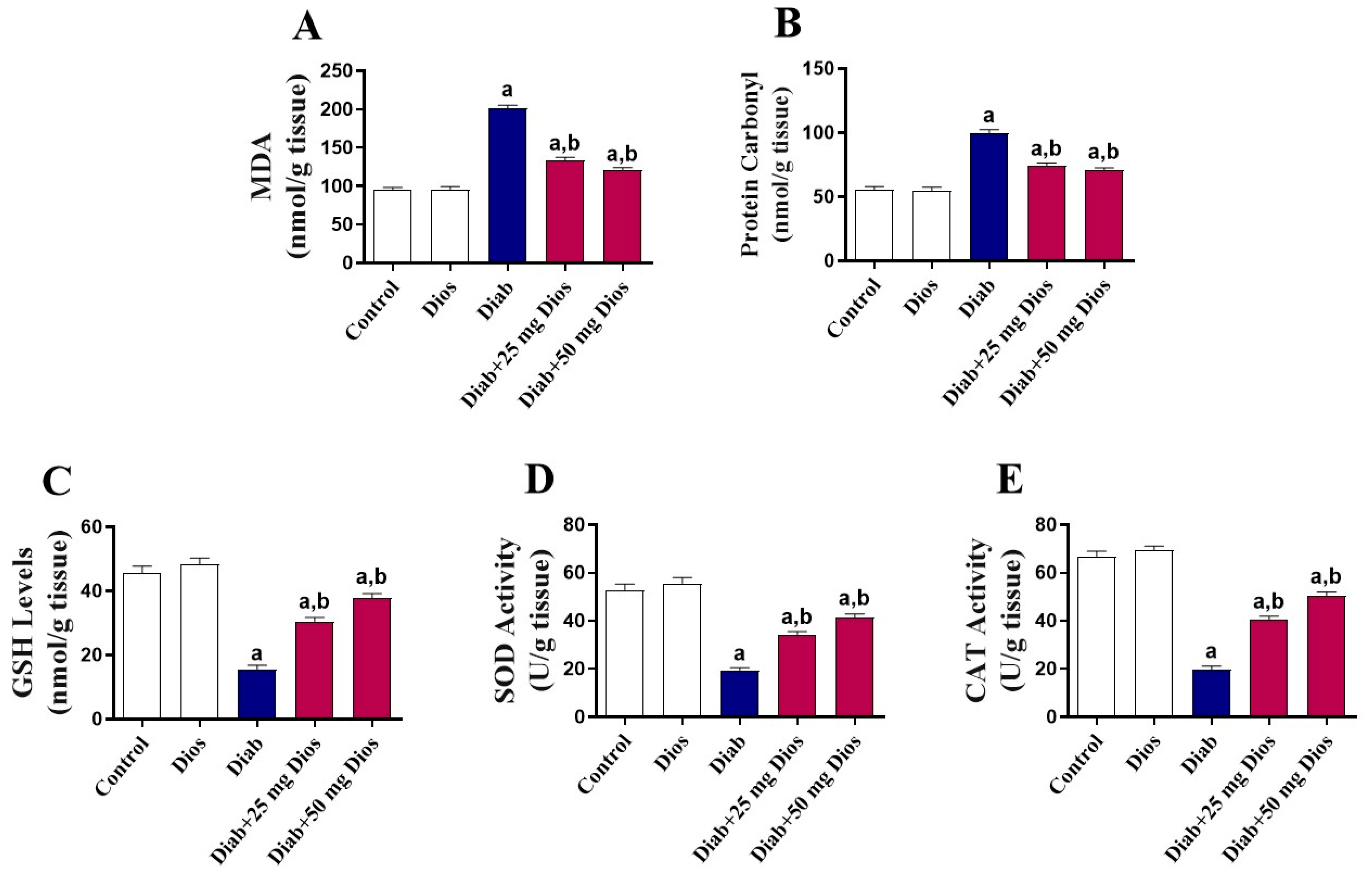

2.3. Mitigation of Oxidative Stress in the Testes of Diabetic Rats by Dios

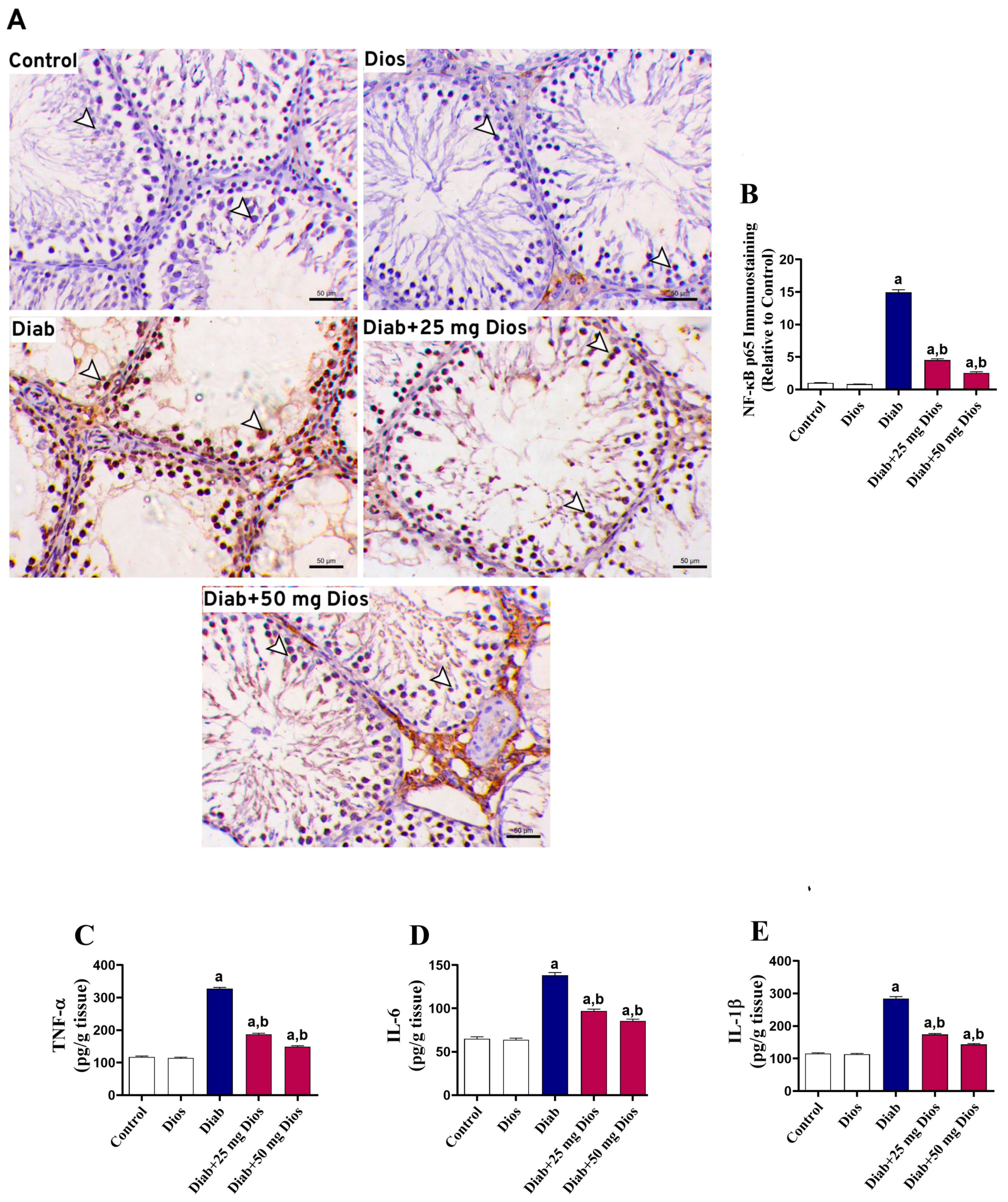

2.4. Diabetes-Induced Testicular Inflammatory Response Is Attenuated by Dios

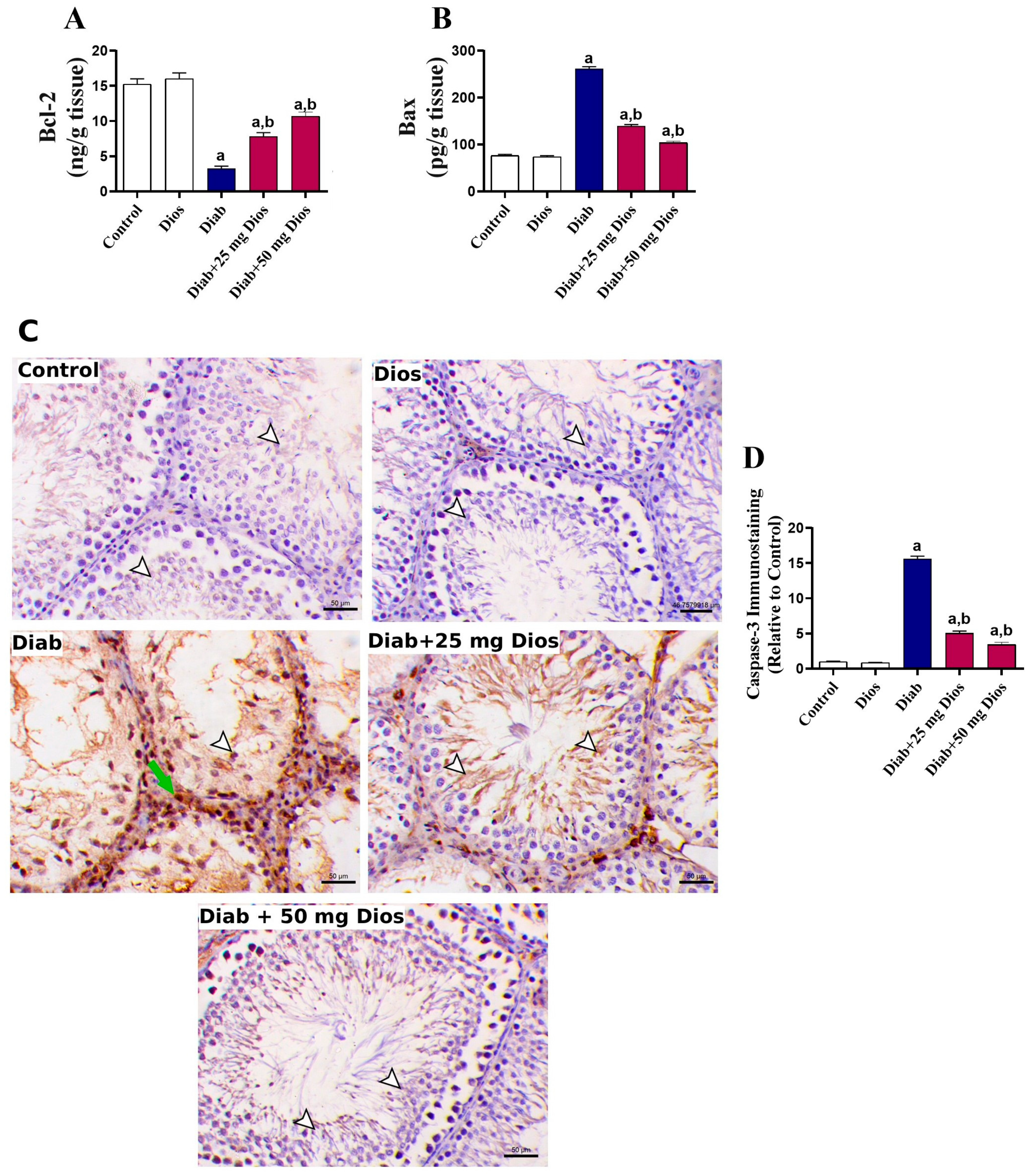

2.5. Alleviation of Testicular Apoptosis in Diabetic Rats by Dios

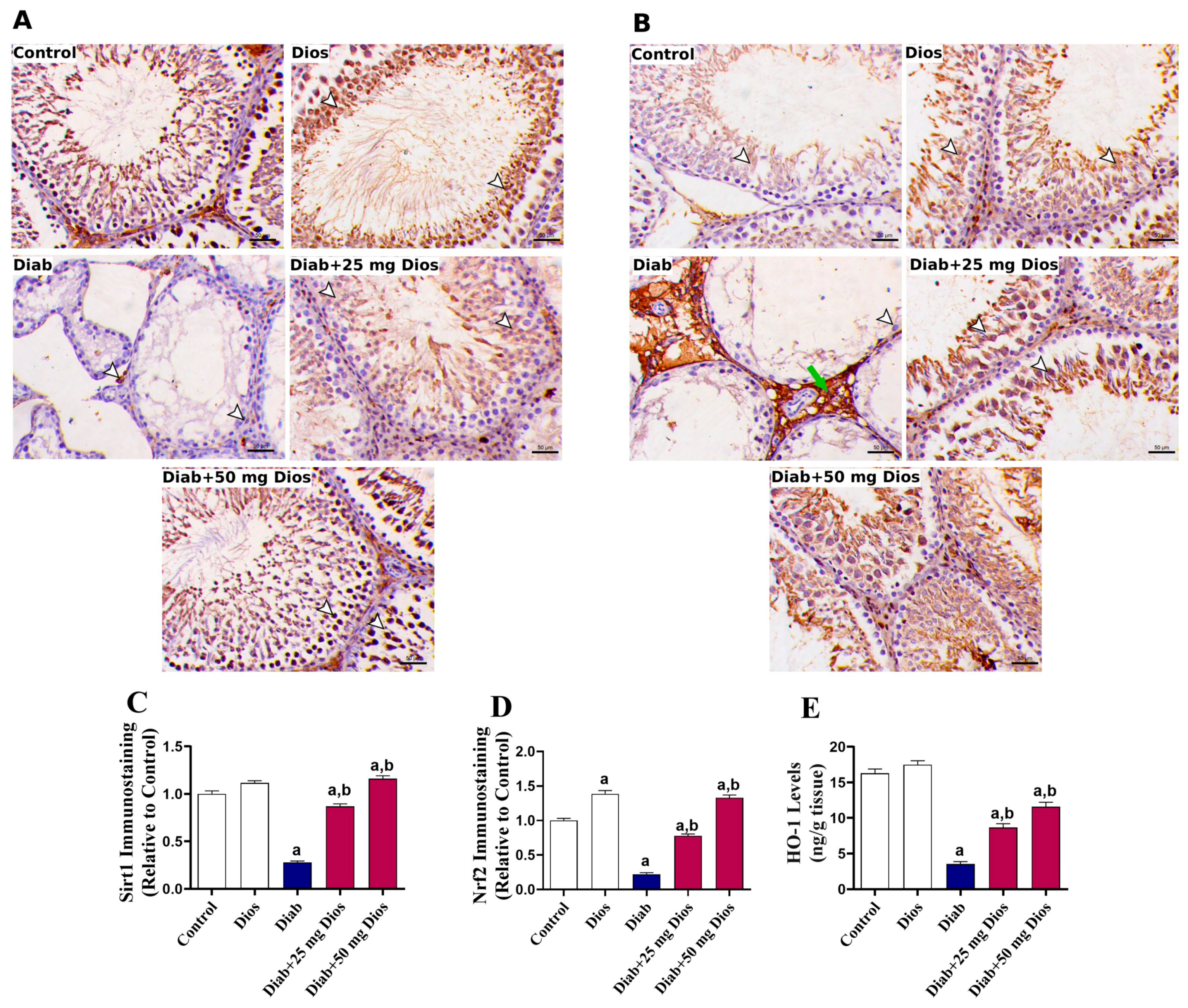

2.6. Dios Modulates Sirt1 and Nrf2/HO-1 in Diabetic Rat Testes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Induction of Diabetes in Rats

4.3. Study Design and Animal Grouping

4.4. Sperm Preparation and Analysis

4.5. Biochemical Analysis

4.6. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis

4.7. Data Representation and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, W.; Tong, L.; Jin, B.; Sun, D. Diabetic Testicular Dysfunction and Spermatogenesis Impairment: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Prospects. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1653975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunay, G.; Nagler, H.M.; Stember, D.S. Reproductive sequelae of diabetes in male patients. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2013, 42, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Chen, J.; Guo, B.; Jiang, C.; Sun, W. Diabetes-induced male infertility: Potential mechanisms and treatment options. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badejogbin, O.C.; Chijioke-Agu, O.E.; Olubiyi, M.V.; Agunloye, M.O. Pathogenesis of testicular dysfunction in diabetes: Exploring the mechanism and therapeutic interventions. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2025, 42, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-khawaldeh, O.; Al-Alami, Z.M.; Althunibat, O.Y.; Abuamara, T.M.; Mihdawi, A.; Abukhalil, M.H. Rosmarinic acid attenuates testicular damage via modulating oxidative stress and apoptosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic albino mice. Stresses 2024, 4, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kaushal, N.; Saleth, L.R.; Ghavami, S.; Dhingra, S.; Kaur, P. Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and autophagy: Balancing the contrary forces in spermatogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Sengupta, P.; Slama, P.; Roychoudhury, S. Oxidative stress, testicular inflammatory pathways, and male reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho-Santos, J.; Amaral, S.; Oliveira, P.J. Diabetes and the impairment of reproductive function: Possible role of mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2008, 4, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshnavand, F.; Hojati, V.; Vaezi, G.; Rahbarian, R. The Comparative Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Green Tea and Catechin on Inflammation, Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in the Testicular Tissue of Diabetic Rats. J. Biol. Stud. 2022, 4, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-S.; Wu, C.-Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Hu, Q.-Q.; Sun, R.-Y.; Pan, M.-J.; Lu, X.-Y.; Zhu, T.; Luo, S.; Yang, H.-J. The protective effects of icariin against testicular dysfunction in type 1 diabetic mice Via AMPK-mediated Nrf2 activation and NF-κB p65 inhibition. Phytomedicine 2024, 123, 155217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nna, V.U.; Bakar, A.B.A.; Ahmad, A.; Mohamed, M. Diabetes-induced testicular oxidative stress, inflammation, and caspase-dependent apoptosis: The protective role of metformin. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 126, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, Z.; Sedaghat, R.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Roghani, M. Diosgenin ameliorates testicular damage in streptozotocin-diabetic rats through attenuation of apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 70, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Yin, G.; Li, Q.Q.; Zeng, Q.; Duan, J. Diabetes mellitus causes male reproductive dysfunction: A review of the evidence and mechanisms. In Vivo 2021, 35, 2503–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, H.; Shrivastava, V.K.; Amir, M. Diabetes mellitus and impairment of male reproductive function: Role of hypothalamus pituitary testicular axis and reactive oxygen species. Iran. J. Diabetes Obes. 2016, 8, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chilukoti, S.R.; Sahu, C.; Jena, G. Protective role of eugenol against diabetes-induced oxidative stress, DNA damage, and apoptosis in rat testes. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e23593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, R.-J.; Yang, J.-M.; Hai, D.-M.; Liu, N.; Ma, L.; Lan, X.-B.; Niu, J.-G.; Zheng, P.; Yu, J.-Q. Interplay between male reproductive system dysfunction and the therapeutic effect of flavonoids. Fitoterapia 2020, 147, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtadi, S.; Shariati, S.; Mansouri, E.; Khodayar, M.J. Nephroprotective effect of diosmin against sodium arsenite-induced renal toxicity is mediated via attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation in mice. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 197, 105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, R.I.; Aboutaleb, A.S.; Younis, N.S.; Ahmed, H.I. Diosmin mitigates gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats: Insights on miR-21 and-155 expression, Nrf2/HO-1 and p38-MAPK/NF-κB pathways. Toxics 2023, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyovwi, M.O.; Ben-Azu, B.; Tesi, E.P.; Ojetola, A.A.; Olowe, T.G.; Joseph, U.G.; Emojevwe, V.; Oghenetega, O.B.; Rotu, R.A.; Rotu, R.A. Diosmin protects the testicles from doxorubicin-induced damage by increasing steroidogenesis and suppressing oxido-inflammation and apoptotic mediators. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 15, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Shao, J. Diosmin ameliorates LPS-induced depression-like behaviors in mice: Inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress in the prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 206, 110843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.N.; Mumtaz, S. Prunin: An emerging anticancer flavonoid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, M.L.; Parihar, P.; Solanki, I.; Parihar, M.S. Flavonoids in modulation of cell survival signalling pathways. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, J.; He, W.; Ma, B.; Fan, H. Hyperoside, a natural flavonoid compound, attenuates Triptolide-induced testicular damage by activating the Keap1-Nrf2 and SIRT1-PGC1α signalling pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 74, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, F.H.; Soliman, N.A.; Abo-Elnasr, S.E.; Mahmoud, H.A.; Abdel Ghafar, M.T.; Elkholy, R.A.; ELshora, O.A.; Mariah, R.A.; Amin Mashal, S.S.; El Saadany, A.A. Fisetin ameliorates oxidative glutamate testicular toxicity in rats via central and peripheral mechanisms involving SIRT1 activation. Redox Rep. 2022, 27, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.-Y.; Chen, H.; Zirkin, B. Sirt1 and Nrf2: Regulation of Leydig cell oxidant/antioxidant intracellular environment and steroid formation. Biol. Reprod. 2021, 105, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huwait, E.; Mobashir, M. Potential and therapeutic roles of diosmin in human diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekar, M.; Baskaran, P.; Mary, J.; Sivakumar, M.; Selvam, M. Revisiting Diosmin for their potential biological properties and applications. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.; Laila, I.M.I. Protective and restorative potency of diosmin natural flavonoid compound against tramadol-induced testicular damage and infertility in male rats. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Elghait, A.T.; Elgamal, D.A.; Abd el-Rady, N.M.; Hosny, A.; Abd El, E.Z.A.A.; Ali, F.E. Novel protective effect of diosmin against cisplatin-induced prostate and seminal vesicle damage: Role of oxidative stress and apoptosis. Tissue Cell 2022, 79, 101961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.M.; Abo-Salem, O.M.; El Esawy, B.H.; El Askary, A. The potential protective effects of diosmin on streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 359, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Mundhe, N.; Borgohain, M.; Chowdhury, L.; Kwatra, M.; Bolshette, N.; Ahmed, A.; Lahkar, M. Diosmin modulates the NF-kB signal transduction pathways and downregulation of various oxidative stress markers in alloxan-induced diabetic nephropathy. Inflammation 2016, 39, 1783–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaala, N.; El-Shoura, E.A.; Khalaf, M.M.; Zafaar, D.; AN Ahmed, A.; Atwa, A.M.; Abdel-Wahab, B.A.; Ahmed, Y.H.; Abomandour, A.; Salem, E.A. Reno-protective impact of diosmin and perindopril in amikacin-induced nephrotoxicity rat model: Modulation of SIRT1/p53/C-FOS, NF-κB-p65, and keap-1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2025, 47, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.B.; El-Lakkany, N.M.; El-Din, S.H.S.; Hammam, O.A.; Samir, S. Diosmin alleviates ulcerative colitis in mice by increasing Akkermansia muciniphila abundance, improving intestinal barrier function, and modulating the NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, N.; Raju, R. Sirtuin regulation in aging and injury. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 2442–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Negative regulation of inflammation by SIRT1. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 67, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-W.; Zhao, G.-J.; Li, X.-L.; Hong, G.-L.; Li, M.-F.; Qiu, Q.-M.; Wu, B.; Lu, Z.-Q. SIRT1 exerts protective effects against paraquat-induced injury in mouse type II alveolar epithelial cells by deacetylating NRF2 in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Ubaid, S. Role of silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1) in regulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An overview of Nrf2 signaling pathway and its role in inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Long, P.; Yan, W.; Chen, T.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. ALDH2 attenuates early-stage STZ-induced aged diabetic rats retinas damage via Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway. Life Sci. 2018, 215, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.H.; Shaheen, S.Y.; Alhusaini, A.M.; Mahmoud, A.M. Simvastatin mitigates diabetic nephropathy by upregulating farnesoid X receptor and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling and attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation in rats. Life Sci. 2024, 340, 122445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, K.; Chen, M.; Li, X. Allisartan isoproxil attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation through the SIRT1/Nrf2/NF-κB signalling pathway in diabetic cardiomyopathy rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yin, K.; Shen, Y.; Lin, K.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; Xin, W.; Xu, Y. Formononetin attenuates renal tubular injury and mitochondrial damage in diabetic nephropathy partly via regulating Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 901234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, Y.; Cai, L. Protection by sulforaphane from type 1 diabetes-induced testicular apoptosis is associated with the up-regulation of Nrf2 expression and function. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 279, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkali, G.; Aksakal, M.; Kaya, Ş.Ö. Protective effects of carvacrol against diabetes-induced reproductive damage in male rats: Modulation of Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathway and inhibition of Nf-kB-mediated testicular apoptosis and inflammation. Andrologia 2021, 53, e13899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hroob, A.M.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Alghonmeen, R.D.; Mahmoud, A.M. Ginger alleviates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis and protects rats against diabetic nephropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althunibat, O.Y.; Al Hroob, A.M.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Germoush, M.O.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Mahmoud, A.M.J.L.s. Fisetin ameliorates oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Life Sci. 2019, 221, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukhalil, M.H.; Althunibat, O.Y.; Aladaileh, S.H.; Al-Amarat, W.; Obeidat, H.M.; Al-Khawalde, A.A.-M.A.; Hussein, O.E.; Alfwuaires, M.A.; Algefare, A.I.; Alanazi, K.M. Galangin attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy through modulating oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladaileh, S.; Al-Swailmi, F.; Abukhalil, M.; Shalayel, M. Galangin protects against oxidative damage and attenuates inflammation and apoptosis via modulation of NF-κB p65 and caspase-3 signaling molecules in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 2021, 72, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, S.N.; Reddy, N.M.; Patil, K.R.; Nakhate, K.T.; Ojha, S.; Patil, C.R.; Agrawal, Y.O. Challenges and issues with streptozotocin-induced diabetes–a clinically relevant animal model to understand the diabetes pathogenesis and evaluate therapeutics. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2016, 244, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol. Res. 2001, 50, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahdi, A.M.A.; John, A.; Raza, H. Elucidation of molecular mechanisms of streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress, apoptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction in Rin-5F pancreatic β-cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7054272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pari, L.; Srinivasan, S. Antihyperglycemic effect of diosmin on hepatic key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2010, 64, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.C.; Lin, M.H.; Cheng, J.T.; Wu, M.C. Antihyperglycaemic action of diosmin, a citrus flavonoid, is induced through endogenous β-endorphin in type I-like diabetic rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017, 44, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrefaei, G.I.; Almohaimeed, H.M.; Algaidi, S.A.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; AbdAllah, F.M.; Al-Abbas, N.S.; Ayuob, N. Cinnamon and ginger extracts attenuate diabetes-induced inflammatory testicular injury in rats and modulating SIRT1 expression. J. Men’s Health 2023, 19, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- González, P.; Lozano, P.; Ros, G.; Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: An integral, updated and critical overview of their metabolic interconnections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, K. Evidence of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunctions in the testis of prepubertal diabetic rats. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2009, 21, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrilatha, B. Early oxidative stress in testis and epididymal sperm in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice: Its progression and genotoxic consequences. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 23, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, N.; Bahmani, M.; Kheradmand, A.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. The impact of oxidative stress on testicular function and the role of antioxidants in improving it: A review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2017, 11, IE01–IE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, A.; Sedaghat, R.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Roghani, M. Hesperetin, a citrus flavonoid, attenuates testicular damage in diabetic rats via inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Life Sci. 2018, 210, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Das, A.K.; Sil, P.C. Taurine ameliorates oxidative stress induced inflammation and ER stress mediated testicular damage in STZ-induced diabetic Wistar rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 124, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, B.; Guo, L.; Cui, J.; Wang, G.; Shi, X.; Zhang, X.; Mellen, N. Exacerbation of diabetes-induced testicular apoptosis by zinc deficiency is most likely associated with oxidative stress, p38 MAPK activation, and p53 activation in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 200, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosulich, S.C.; Savory, P.J.; Clarke, P.R. Bcl-2 regulates amplification of caspase activation by cytochrome c. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Jin, H.; Lv, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Quality Control and Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.-R.; Dong, H.-S.; Yang, W.-X. Regulators in the apoptotic pathway during spermatogenesis: Killers or guards? Gene 2016, 582, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattori, V.; Rasquel-Oliveira, F.S.; Artero, N.A.; Ferraz, C.R.; Borghi, S.M.; Casagrande, R.; Verri, W.A., Jr. Diosmin treats lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory pain and peritonitis by blocking NF-κB activation in mice. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, X.; Tang, C.; Ren, C.; Bao, X.; Deng, Z.; Cao, X.; Zou, J.; Zhang, Q. Cordycepin, a major bioactive component of cordyceps militaris, ameliorates diabetes-induced testicular damage through the Sirt1/Foxo3a pathway. Andrologia 2022, 54, e14294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H. MicroRNA-34a targets sirtuin 1 and leads to diabetes-induced testicular apoptotic cell death. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 96, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, H.; Dessain, S.K.; Eaton, E.N.; Imai, S.-I.; Frye, R.A.; Pandita, T.K.; Guarente, L.; Weinberg, R.A. hSIR2SIRT1 functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell 2001, 107, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Syed, H.; Amjad, S.; Baig, M.; Khan, T.A.; Rehman, R. Interplay between oxidative stress, SIRT1, reproductive and metabolic functions. Curr. Res. Physiol. 2021, 4, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawar, M.B.; Sohail, A.M.; Li, W. SIRT1: A key player in male reproduction. Life 2022, 12, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatone, C.; Di Emidio, G.; Barbonetti, A.; Carta, G.; Luciano, A.M.; Falone, S.; Amicarelli, F. Sirtuins in gamete biology and reproductive physiology: Emerging roles and therapeutic potential in female and male infertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens, M.; Maresh, J.G.; Yanagimachi, R.; Maeda, G.; Allsopp, R. Sirt1 deficiency attenuates spermatogenesis and germ cell function. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kang, K.; Bao, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, B.; Hu, G.; Wu, J. Research Progress on the Interaction Between SIRT1 and Mitochondrial Biochemistry in the Aging of the Reproductive System. Biology 2025, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, H.H.; Fikry, E.M.; Alsufyani, S.E.; Ashour, A.M.; El-Sheikh, A.A.; Darwish, H.W.; Al-Hossaini, A.M.; Saad, M.A.; Al-Shorbagy, M.Y.; Eid, A.H. Stimulation of autophagy by dapagliflozin mitigates cadmium-induced testicular dysfunction in rats: The role of AMPK/mTOR and SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardyn, J.D.; Ponsford, A.H.; Sanderson, C.M. Dissecting molecular cross-talk between Nrf2 and NF-κB response pathways. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, B.N.; Lawson, G.; Chan, J.Y.; Banuelos, J.; Cortés, M.M.; Hoang, Y.D.; Ortiz, L.; Rau, B.A.; Luderer, U. Knockout of the transcription factor NRF2 disrupts spermatogenesis in an age-dependent manner. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, H.H.; Hozayen, W.G.; Khaliefa, A.K.; El-Kenawy, A.E.; Ali, T.M.; Ahmed, O.M. Diosmin and trolox have anti-arthritic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potencies in complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced arthritic male Wistar rats: Roles of NF-κB, iNOS, Nrf2 and MMPs. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.N.; Gul, K.; Mumtaz, S. Isorhamnetin: Reviewing recent developments in anticancer mechanisms and nanoformulation-driven delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, L.; Talha Khalil, A.; Ahsan Shahid, S.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Almarhoon, Z.M.; Alalmaie, A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D. Diosmin: A promising phytochemical for functional foods, nutraceuticals and cancer therapy. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 6070–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, C. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery of natural compounds and phytochemicals for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2019, 62, 91–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pingili, R.B.; Vemulapalli, S.; Narra, U.B.; Potluri, S.V.; Kilaru, N.B. Diosmin attenuates paracetamol-induced hepato-and nephrotoxicity via inhibition of CY2E1-mediated metabolism in rats. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 13, 096–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayn’Al-marddyah, A.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Althunibat, O.Y.; Jaber, F.A.; Alaryani, F.S.; Saleh, A.M.; Albalawi, A.E.; Alhasani, R.H. Taxifolin mitigates cisplatin-induced testicular damage by reducing inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mice. Tissue Cell 2025, 93, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranaamnuay, K. Comparison of different methods for sperm vitality assessment in frozen-thawed Holstein bull semen. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2019, 49, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.L.; Garland, D.; Oliver, C.N.; Amici, A.; Climent, I.; Lenz, A.-G.; Ahn, B.-W.; Shaltiel, S.; Stadtman, E.R. [49] Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; Volume 186, pp. 464–478. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, O.W. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal. Biochem. 1980, 106, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitz, D.R.; Oberley, L.W. An assay for superoxide dismutase activity in mammalian tissue homogenates. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 179, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. [13] Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 105, pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Gamble, M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aladaileh, S.H.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Alfwuaires, M.A.; Algefare, A.I.; Imran, M.R.; Anjum, S.; Alzahrani, S.; Alsubhi, W.A.; Karimulla, S.; Al-Shammari, A.H. Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis and Restoration of Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling by Diosmin Protect Against Diabetes-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031268

Aladaileh SH, Abukhalil MH, Alfwuaires MA, Algefare AI, Imran MR, Anjum S, Alzahrani S, Alsubhi WA, Karimulla S, Al-Shammari AH. Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis and Restoration of Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling by Diosmin Protect Against Diabetes-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031268

Chicago/Turabian StyleAladaileh, Saleem H., Mohammad H. Abukhalil, Manal A. Alfwuaires, Abdulmohsen I. Algefare, Mohd Rasheeduddin Imran, Sayeeda Anjum, Shatha Alzahrani, Wael A. Alsubhi, Shaik Karimulla, and Ayyad Hazzaa Al-Shammari. 2026. "Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis and Restoration of Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling by Diosmin Protect Against Diabetes-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031268

APA StyleAladaileh, S. H., Abukhalil, M. H., Alfwuaires, M. A., Algefare, A. I., Imran, M. R., Anjum, S., Alzahrani, S., Alsubhi, W. A., Karimulla, S., & Al-Shammari, A. H. (2026). Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis and Restoration of Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling by Diosmin Protect Against Diabetes-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031268