High-Phosphate-Induced Hypertension: The Pathogenic Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23) Signaling in Sympathetic Nervous System Activation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pi and Blood Pressure

3. Mechanisms Underlying High Pi-Induced Hypertension

3.1. Role of FGF23 in Sympathetic Nervous System

3.2. FGF Receptors Mediating the FGF23 Effect

3.3. Role of Klotho in Sympathetic Nervous System

3.4. Renal Mechanisms

3.5. Endothelial Dysfunction and Vascular Remodeling

4. Phosphotoxicity and Hypertension in CKD

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABP | Arterial blood pressure |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| EPR | Exercise pressor reflex |

| FGF23 | Fibroblast growth factor 23 |

| FGFRs | Fibroblast growth factor receptors |

| FMD | Flow-mediated dilation |

| IA | Intraarterial |

| ICV | Intracerebroventricular |

| LVH | Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NTS | Nucleus tractus solitarius |

| Pi | Phosphate |

| PWV | Pulse wave velocity |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RVLM | Rostral ventrolateral medulla |

| SNA | Sympathetic nerve activity |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Hypertension: The Race Against a Silent Killer; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–276. [Google Scholar]

- Grillo, A.; Salvi, L.; Coruzzi, P.; Salvi, P.; Parati, G. Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Yu, M.Y.; Shin, J. Effect of low sodium and high potassium diet on lowering blood pressure and cardiovascular events. Clin. Hypertens. 2024, 30, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Mizuno, M.; Vongpatanasin, W. Phosphate, the forgotten mineral in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2019, 28, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Gutekunst, L.; Mehrotra, R.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Bross, R.; Shinaberger, C.S.; Noori, N.; Hirschberg, R.; Benner, D.; Nissenson, A.R.; et al. Understanding sources of dietary phosphorus in the treatment of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.R.; Anderson, C. Dietary Phosphorus Intake and the Kidney. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, J.; Campbell, K.; Ferguson, M.; Day, S.; Rossi, M. Prevalence of Phosphorus-Based Additives in the Australian Food Supply: A Challenge for Dietary Education? J. Ren. Nutr. 2015, 25, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Jules, D.E.; Goldfarb, D.S.; Pompeii, M.L.; Sevick, M.A. Phosphate Additive Avoidance in Chronic Kidney Disease. Diabetes Spectr. 2017, 30, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, K.; Razcon-Echeagaray, A.; Griffiths, M.; Mager, D.R.; Richard, C. Currently Available Handouts for Low Phosphorus Diets in Chronic Kidney Disease Continue to Restrict Plant Proteins and Minimally Processed Dairy Products. J. Ren. Nutr. 2023, 33, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemming, E.W.; Pitsi, T. The Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2022—Food consumption and nutrient intake in the adult population of the Nordic and Baltic countries. Food Nutr. Res. 2022, 66, 8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Parekh, N.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A.; Chang, V.W. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Ramos, E.; Tomaino, L.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Gomez, S.F.; Warnberg, J.; Oses, M.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Gusi, N.; Aznar, S.; et al. Trends in Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish Children and Adolescents across Two Decades. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, S.T.; Chang, A.R.; Selvin, E.; Rebholz, C.M.; Appel, L.J. Dietary Sources of Phosphorus among Adults in the United States: Results from NHANES 2001–2014. Nutrients 2017, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Y.; You, H.Z.; Wang, M.J.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, X.Y.; Liu, J.F.; Chen, J. High-phosphorus diet controlled for sodium elevates blood pressure in healthy adults via volume expansion. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2021, 23, 849–859. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, J.; Scanni, R.; Bestmann, L.; Hulter, H.N.; Krapf, R. A Controlled Increase in Dietary Phosphate Elevates BP in Healthy Human Subjects. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2089–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivo, R.E.; Hale, S.L.; Diamantidis, C.J.; Bhavsar, N.A.; Tyson, C.C.; Tucker, K.L.; Carithers, T.C.; Kestenbaum, B.; Muntner, P.; Tanner, R.M.; et al. Dietary Phosphorus and Ambulatory Blood Pressure in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2019, 32, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, S.T.; Rebholz, C.M.; Medabalimi, S.; Hu, E.A.; Xu, Z.; Selvin, E.; Appel, L.J. Dietary phosphorus intake and blood pressure in adults: A systematic review of randomized trials and prospective observational studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, S.T.; Rebholz, C.M.; Mitchell, D.C.; Selvin, E.; Appel, L.J. The association of dietary phosphorus with blood pressure: Results from a secondary analysis of the PREMIER trial. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2020, 34, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Sacks, F.; Pfeffer, M.; Gao, Z.; Curhan, G.; Cholesterol And Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 2005, 112, 2627–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialla, J.J.; Wolf, M. Roles of phosphate and fibroblast growth factor 23 in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2014, 10, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, R.N.; Collins, A.J.; Herzog, C.A.; Ishani, A.; Kalra, P.A. Serum phosphorus levels associate with coronary atherosclerosis in young adults. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ix, J.H.; De Boer, I.H.; Peralta, C.A.; Adeney, K.L.; Duprez, D.A.; Jenny, N.S.; Siscovick, D.S.; Kestenbaum, B.R. Serum phosphorus concentrations and arterial stiffness among individuals with normal kidney function to moderate kidney disease in MESA. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.T.; Robinson-Cohen, C.; de Oliveira, M.C.; Kostina, A.; Nettleton, J.A.; Ix, J.H.; Nguyen, H.; Eng, J.; Lima, J.A.; Siscovick, D.S.; et al. Dietary phosphorus is associated with greater left ventricular mass. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozic, M.; Panizo, S.; Sevilla, M.A.; Riera, M.; Soler, M.J.; Pascual, J.; Lopez, I.; Freixenet, M.; Fernandez, E.; Valdivielso, J.M. High phosphate diet increases arterial blood pressure via a parathyroid hormone mediated increase of renin. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, M.; Mitchell, J.H.; Crawford, S.; Huang, C.L.; Maalouf, N.; Hu, M.C.; Moe, O.W.; Smith, S.A.; Vongpatanasin, W. High dietary phosphate intake induces hypertension and augments exercise pressor reflex function in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 311, R39–R48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latic, N.; Peitzsch, M.; Zupcic, A.; Pietzsch, J.; Erben, R.G. Long-Term Excessive Dietary Phosphate Intake Increases Arterial Blood Pressure, Activates the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System, and Stimulates Sympathetic Tone in Mice. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanev, P.; Ujas, T.A.; Kim, H.K.; Fujikawa, T.; Isozumi, N.; Mori, E.; Turchan-Cholewo, J.; Stuart, C.; Sturgill, R.; Birnbaum, S.G.; et al. High dietary phosphate intake induces anxiety in normal male mice. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2025, 49, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agoro, R.; White, K.E. Regulation of FGF23 production and phosphate metabolism by bone-kidney interactions. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe-Johnson, A.L.; Alonso, A.; Selvin, E.; Bower, J.K.; Pankow, J.S.; Agarwal, S.K.; Lutsey, P.L. Serum fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident hypertension: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhabue, E.; Montag, S.; Reis, J.P.; Pool, L.R.; Mehta, R.; Yancy, C.W.; Zhao, L.; Wolf, M.; Gutierrez, O.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. FGF23 (Fibroblast Growth Factor-23) and Incident Hypertension in Young and Middle-Aged Adults: The CARDIA Study. Hypertension 2018, 72, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, D.A.; Katz, R.; Kritchevsky, S.; Ix, J.H.; Shlipak, M.G.; Newman, A.B.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Fried, L.F.; Sarnak, M.; Gutierrez, O.M. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Blood Pressure in Older Adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Hypertension 2020, 76, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, R.; Diaz-Tocados, J.M.; Pendon-Ruiz de Mier, M.V.; Robles, A.; Salmeron-Rodriguez, M.D.; Ruiz, E.; Vergara, N.; Aguilera-Tejero, E.; Raya, A.; Ortega, R.; et al. Increased Phosphaturia Accelerates The Decline in Renal Function: A Search for Mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Fukazawa, A.; Smith, S.A.; Mizuno, M.; Rothermel, B.A.; Fujikawa, T.; Galvan, M.; Gautron, L.; Pastor, J.V.; Carroll, I.J.; et al. High Dietary Phosphate Intake Induces Hypertension and Sympathetic Overactivation via Central Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Signaling. Circulation 2025, 152, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, P.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, W.; Cherukuru, R.; Adams, M.A.; Turner, M.E.; Rhee, E.P. Glycerol-3-phosphate contributes to the increase in FGF23 production in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2025, 328, F165–F172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunert, S.K.; Hartmann, H.; Haffner, D.; Leifheit-Nestler, M. Klotho and fibroblast growth factor 23 in cerebrospinal fluid in children. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2017, 35, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cao, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, F.; Xiong, R.; Xu, Z.; Luo, X.; Li, G.; Tan, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid FGF23 levels correlate with a measure of impulsivity. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 264, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami Aleagha, M.S.; Siroos, B.; Allameh, A.; Shakiba, S.; Ranji-Burachaloo, S.; Harirchian, M.H. Calcitriol, but not FGF23, increases in CSF and serum of MS patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 328, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Paz Oliveira, G.; Elias, R.M.; Peres Fernandes, G.B.; Moyses, R.; Tufik, S.; Bichuetti, D.B.; Coelho, F.M.S. Decreased concentration of klotho and increased concentration of FGF23 in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with narcolepsy. Sleep. Med. 2021, 78, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursem, S.R.; Diepenbroek, C.; Bacic, V.; Unmehopa, U.A.; Eggels, L.; Maya-Monteiro, C.M.; Heijboer, A.C.; la Fleur, S.E. Localization of fibroblast growth factor 23 protein in the rat hypothalamus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 54, 5261–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Yoshioka, M.; Itoh, N. Identification of a novel fibroblast growth factor, FGF-23, preferentially expressed in the ventrolateral thalamic nucleus of the brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 277, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszczyk, A.M.; Nettles, D.; Pollock, T.A.; Fox, S.; Garcia, M.L.; Wang, J.; Quarles, L.D.; King, G.D. FGF-23 Deficiency Impairs Hippocampal-Dependent Cognitive Function. eNeuro 2019, 6, e0469-18.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, N.; Onimaru, H.; Yamagata, A.; Ito, S.; Imakiire, T.; Kumagai, H. Rostral ventrolateral medulla neuron activity is suppressed by Klotho and stimulated by FGF23 in newborn Wistar rats. Auton. Neurosci. 2020, 224, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.P.; Peng, L.N.; Chou, K.H.; Liu, L.K.; Lee, W.J.; Lin, C.P.; Chen, L.K.; Wang, P.N. High Circulatory Phosphate Level Is Associated with Cerebral Small-Vessel Diseases. Transl. Stroke Res. 2019, 10, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Vierthaler, L.; Tang, W.; Zhou, J.; Quarles, L.D. FGFR3 and FGFR4 do not mediate renal effects of FGF23. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattineni, J.; Bates, C.; Twombley, K.; Dwarakanath, V.; Robinson, M.L.; Goetz, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Baum, M. FGF23 decreases renal NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression and induces hypophosphatemia in vivo predominantly via FGF receptor 1. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009, 297, F282–F291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattineni, J.; Alphonse, P.; Zhang, Q.; Mathews, N.; Bates, C.M.; Baum, M. Regulation of renal phosphate transport by FGF23 is mediated by FGFR1 and FGFR4. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2014, 306, F351–F358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuro, O.M.; Moe, O.W. FGF23-alphaKlotho as a paradigm for a kidney-bone network. Bone 2017, 100, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grabner, A.; Amaral, A.P.; Schramm, K.; Singh, S.; Sloan, A.; Yanucil, C.; Li, J.; Shehadeh, L.A.; Hare, J.M.; David, V.; et al. Activation of Cardiac Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 Causes Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner, A.; Schramm, K.; Silswal, N.; Hendrix, M.; Yanucil, C.; Czaya, B.; Singh, S.; Wolf, M.; Hermann, S.; Stypmann, J.; et al. FGF23/FGFR4-mediated left ventricular hypertrophy is reversible. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leifheit-Nestler, M.; Grabner, A.; Hermann, L.; Richter, B.; Schmitz, K.; Fischer, D.C.; Yanucil, C.; Faul, C.; Haffner, D. Vitamin D treatment attenuates cardiac FGF23/FGFR4 signaling and hypertrophy in uremic rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Cai, C.; Xiao, Z.; Quarles, L.D. FGF23 induced left ventricular hypertrophy mediated by FGFR4 signaling in the myocardium is attenuated by soluble Klotho in mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020, 138, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fu, L.; Sun, J.; Huang, Z.; Fang, M.; Zinkle, A.; Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Structural basis for FGF hormone signalling. Nature 2023, 618, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Rothermel, B.; Vega, R.B.; Frey, N.; McKinsey, T.A.; Olson, E.N.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Williams, R.S. Independent signals control expression of the calcineurin inhibitory proteins MCIP1 and MCIP2 in striated muscles. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, E61–E68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, V.; Rothermel, B.A. Calcineurin signaling in the heart: The importance of time and place. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2017, 103, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.C.; Shi, M.; Cho, H.J.; Adams-Huet, B.; Paek, J.; Hill, K.; Shelton, J.; Amaral, A.P.; Faul, C.; Taniguchi, M.; et al. Klotho and phosphate are modulators of pathologic uremic cardiac remodeling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanbay, M.; Demiray, A.; Afsar, B.; Covic, A.; Tapoi, L.; Ureche, C.; Ortiz, A. Role of Klotho in the Development of Essential Hypertension. Hypertension 2021, 77, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.H.; Si, L.Y.; Li, X.J.; Yang, Q.H.; Xiao, H. A potential regulatory single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter of the Klotho gene may be associated with essential hypertension in the Chinese Han population. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citterio, L.; Delli Carpini, S.; Lupoli, S.; Brioni, E.; Simonini, M.; Fontana, S.; Zagato, L.; Messaggio, E.; Barlassina, C.; Cusi, D.; et al. Klotho Gene in Human Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuro-o, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Suga, T.; Utsugi, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Kurabayashi, M.; Kaname, T.; Kume, E.; et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 1997, 390, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, D.C.; Khobahy, I.; Pastor, J.; Kuro, O.M.; Liu, X. Nuclear localization of Klotho in brain: An anti-aging protein. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1483.e25–1483.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba, R.D.; Moghekar, A.R.; Hu, J.; Sun, K.; Turner, R.; Ferrucci, L.; O’Brien, R. Klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid of adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 558, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Z. RNAi silencing of brain klotho potentiates cold-induced elevation of blood pressure via the endothelin pathway. Physiol. Genomics 2010, 41, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.C.; Moe, O.W. Phosphate and Cellular Senescence. In Phosphate Metabolism. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Razzaque, M.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, R.; Yamamoto, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Namba-Hamano, T.; Minami, S.; Sakai, S.; Matsuda, J.; Hesaka, A.; Yonishi, H.; et al. Autophagy protects kidney from phosphate-induced mitochondrial injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 524, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maique, J.; Flores, B.; Shi, M.; Shepard, S.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, S.; Moe, O.W.; Hu, M.C. High Phosphate Induces and Klotho Attenuates Kidney Epithelial Senescence and Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Mann-Collura, O.; Fling, J.; Edara, N.; Hetz, R.; Razzaque, M.S. High phosphate actively induces cytotoxicity by rewiring pro-survival and pro-apoptotic signaling networks in HEK293 and HeLa cells. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e20997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.J.; Bhandari, S.K.; Smith, N.; Chung, J.; Liu, I.L.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Phosphorus and risk of renal failure in subjects with normal renal function. Am. J. Med. 2013, 126, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Chin, H.J.; Na, K.Y.; Joo, K.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.; Han, S.S. Hyperphosphatemia and risks of acute kidney injury, end-stage renal disease, and mortality in hospitalized patients. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Yanucil, C.; Musgrove, J.; Shi, M.; Ide, S.; Souma, T.; Faul, C.; Wolf, M.; Grabner, A. FGFR4 does not contribute to progression of chronic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Schuman, M.; Lei, H.; Sun, Z. Antiaging Gene Klotho Regulates Adrenal CYP11B2 Expression and Aldosterone Synthesis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.S.; Kempe, D.S.; Leibrock, C.B.; Rexhepaj, R.; Siraskar, B.; Boini, K.M.; Ackermann, T.F.; Foller, M.; Hocher, B.; Rosenblatt, K.P.; et al. Hyperaldosteronism in Klotho-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2010, 299, F1171–F1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Kong, J.; Wei, M.; Chen, Z.F.; Liu, S.Q.; Cao, L.P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Borst, M.H.; Vervloet, M.G.; ter Wee, P.M.; Navis, G. Cross talk between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and vitamin D-FGF-23-klotho in chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Muto, T.; Hino, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Fujita, T.; Nakahara, K.; Fukumoto, S.; Yamashita, T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, J.; Sea, J.L.; Chun, R.F.; Lisse, T.S.; Wesseling-Perry, K.; Gales, B.; Adams, J.S.; Salusky, I.B.; Hewison, M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 inhibits extrarenal synthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in human monocytes. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, I.; Okazaki, H.; Gross, P.; Cagnard, J.; Boudot, C.; Maizel, J.; Drueke, T.B.; Massy, Z.A. Direct, acute effects of Klotho and FGF23 on vascular smooth muscle and endothelium. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, K.K.; Denby, L.; Patel, R.K.; Mark, P.B.; Kettlewell, S.; Smith, G.L.; Clancy, M.J.; Delles, C.; Jardine, A.G. Deleterious effects of phosphate on vascular and endothelial function via disruption to the nitric oxide pathway. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, E.; Taketani, Y.; Kitamura, T.; Tanaka, T.; Ohminami, H.; Abuduli, M.; Harada, N.; Yamanaka-Okumura, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Takeda, E. Fluctuating plasma phosphorus level by changes in dietary phosphorus intake induces endothelial dysfunction. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2015, 56, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Jiang, S.; Liao, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, F.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Fei, L.; Cui, Y.; Ren, X.; et al. High phosphate impairs arterial endothelial function through AMPK-related pathways in mouse resistance arteries. Acta Physiol. 2021, 231, e13595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuto, E.; Taketani, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Harada, N.; Isshiki, M.; Sato, M.; Nashiki, K.; Amo, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Higashi, Y.; et al. Dietary phosphorus acutely impairs endothelial function. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, B.Y.; Kaur, J.; Vranish, J.R.; Barbosa, T.C.; Blankenship, J.K.; Smith, S.A.; Fadel, P.J. Effect of acute high-phosphate intake on muscle metaboreflex activation and vascular function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317, H308–H314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, M.A.; Larsson, A.; Lind, L.; Larsson, T.E. Circulating fibroblast growth factor-23 is associated with vascular dysfunction in the community. Atherosclerosis 2009, 205, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsey, P.L.; Alonso, A.; Selvin, E.; Pankow, J.S.; Michos, E.D.; Agarwal, S.K.; Loehr, L.R.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Coresh, J. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000936. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Liaw, L.; Prudovsky, I.; Brooks, P.C.; Vary, C.; Oxburgh, L.; Friesel, R. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in the vasculature. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2015, 17, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkaik, M.; Juni, R.P.; van Loon, E.P.M.; van Poelgeest, E.M.; Kwekkeboom, R.F.J.; Gam, Z.; Richards, W.G.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Eringa, E.C.; et al. FGF23 impairs peripheral microvascular function in renal failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H1414–H1424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, K.; Olauson, H.; Amin, R.; Ponnusamy, A.; Goetz, R.; Taylor, R.F.; Mohammadi, M.; Canfield, A.; Kublickiene, K.; Larsson, T.E. Arterial klotho expression and FGF23 effects on vascular calcification and function. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silswal, N.; Touchberry, C.D.; Daniel, D.R.; McCarthy, D.L.; Zhang, S.; Andresen, J.; Stubbs, J.R.; Wacker, M.J. FGF23 directly impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by increasing superoxide levels and reducing nitric oxide bioavailability. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 307, E426–E436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, B.; Haller, J.; Haffner, D.; Leifheit-Nestler, M. Klotho modulates FGF23-mediated NO synthesis and oxidative stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Pflugers Arch. 2016, 468, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Lu, T.S.; Molostvov, G.; Lee, C.; Lam, F.T.; Zehnder, D.; Hsiao, L.L. Vascular Klotho deficiency potentiates the development of human artery calcification and mediates resistance to fibroblast growth factor 23. Circulation 2012, 125, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialla, J.J.; Lau, W.L.; Reilly, M.P.; Isakova, T.; Yang, H.Y.; Crouthamel, M.H.; Chavkin, N.W.; Rahman, M.; Wahl, P.; Amaral, A.P.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is not associated with and does not induce arterial calcification. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mencke, R.; Harms, G.; Mirkovic, K.; Struik, J.; Van Ark, J.; Van Loon, E.; Verkaik, M.; De Borst, M.H.; Zeebregts, C.J.; Hoenderop, J.G.; et al. Membrane-bound Klotho is not expressed endogenously in healthy or uraemic human vascular tissue. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 108, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Yamagishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Suga, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Masuda, H.; Kurabayashi, M.; Kuro-o, M.; et al. Klotho protein protects against endothelial dysfunction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 248, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, A.J.; Machin, D.R.; Lesniewski, L.A. Mechanisms of Dysfunction in the Aging Vasculature and Role in Age-Related Disease. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jono, S.; McKee, M.D.; Murry, C.E.; Shioi, A.; Nishizawa, Y.; Mori, K.; Morii, H.; Giachelli, C.M. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, E10–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, J.L.; Joannides, A.J.; Skepper, J.N.; McNair, R.; Schurgers, L.J.; Proudfoot, D.; Jahnen-Dechent, W.; Weissberg, P.L.; Shanahan, C.M. Human vascular smooth muscle cells undergo vesicle-mediated calcification in response to changes in extracellular calcium and phosphate concentrations: A potential mechanism for accelerated vascular calcification in ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 2857–2867. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, H.Y.; Giachelli, C.M. Role of the sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter, Pit-1, in vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.E.; Beck, L.; Hill Gallant, K.M.; Chen, Y.; Moe, O.W.; Kuro, O.M.; Moe, S.M.; Aikawa, E. Phosphate in Cardiovascular Disease: From New Insights Into Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutra, T.; Morena, M.; Bargnoux, A.S.; Caporiccio, B.; Canaud, B.; Cristol, J.P. Superoxide production: A procalcifying cell signalling event in osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to calcification media. Free Radic. Res. 2008, 42, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Da Ly, D.; Xia, J.B.; Qi, X.F.; Lee, I.K.; Cha, S.K.; Park, K.S. Oxidative stress by Ca2+ overload is critical for phosphate-induced vascular calcification. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 319, H1302–H1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, H. Transcriptional Programming in Arteriosclerotic Disease: A Multifaceted Function of the Runx2 (Runt-Related Transcription Factor 2). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Byon, C.H.; Yuan, K.; Chen, J.; Mao, X.; Heath, J.M.; Javed, A.; Zhang, K.; Anderson, P.G.; Chen, Y. Smooth muscle cell-specific runx2 deficiency inhibits vascular calcification. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 543–552. [Google Scholar]

- Furmanik, M.; Chatrou, M.; van Gorp, R.; Akbulut, A.; Willems, B.; Schmidt, H.; van Eys, G.; Bochaton-Piallat, M.L.; Proudfoot, D.; Biessen, E.; et al. Reactive Oxygen-Forming Nox5 Links Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Switching and Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Vascular Calcification. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimbo, R.; Kawakami-Mori, F.; Mu, S.; Hirohama, D.; Majtan, B.; Shimizu, Y.; Yatomi, Y.; Fukumoto, S.; Fujita, T.; Shimosawa, T. Fibroblast growth factor 23 accelerates phosphate-induced vascular calcification in the absence of Klotho deficiency. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmarasi, M.; Elmakaty, I.; Elsayed, B.; Elsayed, A.; Zein, J.A.; Boudaka, A.; Eid, A.H. Phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis, hypertension, and aortic dissection. J. Cell Physiol. 2024, 239, e31200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, N.; de Mier, M.V.P.; Rodelo-Haad, C.; Revilla-Gonzalez, G.; Membrives, C.; Diaz-Tocados, J.M.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Torralbo, A.I.; Herencia, C.; Rodriguez-Ortiz, M.E.; et al. The direct effect of fibroblast growth factor 23 on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype and function. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 322–343. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, G.; Biffi, A.; Seravalle, G.; Bertoli, S.; Airoldi, F.; Corrao, G.; Pisano, A.; Mallamaci, F.; Mancia, G.; Zoccali, C. Sympathetic nerve traffic overactivity in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Theodorakopoulou, M.; Ortiz, A.; Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Kanbay, M.; Minutolo, R.; Sarafidis, P.A. Guidelines for the management of hypertension in CKD patients: Where do we stand in 2024? Clin Kidney J 2024, 17, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Campese, V.M.; Middlekauff, H.R. Exercise pressor reflex in humans with end-stage renal disease. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 295, R1188–R1194. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Quyyumi, A.A.; Middlekauff, H.R. Exercise pressor response and arterial baroreflex unloading during exercise in chronic kidney disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 114, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Estrada, J.A.; Fukazawa, A.; Hori, A.; Iwamoto, G.A.; Smith, S.A.; Mizuno, M.; Vongpatanasin, W. Exercise pressor reflex function is augmented in rats with chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2025, 328, R460–R469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, I.; Haffner, D.; Leifheit-Nestler, M. FGF23 and Phosphate-Cardiovascular Toxins in CKD. Toxins 2019, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Jeon-Slaughter, H.; Nguyen, H.; Patel, J.; Sambandam, K.K.; Shastri, S.; Van Buren, P.N. Hyperphosphatemia and its relationship with blood pressure, vasoconstriction, and endothelial cell dysfunction in hypertensive hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalhoub, V.; Shatzen, E.M.; Ward, S.C.; Davis, J.; Stevens, J.; Bi, V.; Renshaw, L.; Hawkins, N.; Wang, W.; Chen, C.; et al. FGF23 neutralization improves chronic kidney disease-associated hyperparathyroidism yet increases mortality. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2543–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marco, G.S.; Reuter, S.; Kentrup, D.; Ting, L.; Ting, L.; Grabner, A.; Jacobi, A.M.; Pavenstadt, H.; Baba, H.A.; Tiemann, K.; et al. Cardioprotective effect of calcineurin inhibition in an animal model of renal disease. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Bansal, A.; Young, K.; Gautam, A.; Donald, J.; Comfort, B.; Montgomery, R. Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability in ESKD-A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 1508–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuki, H.; Mandai, S.; Shiwaku, H.; Koide, T.; Takahashi, N.; Yanagi, T.; Inaba, S.; Ida, S.; Fujiki, T.; Mori, Y.; et al. Chronic kidney disease causes blood-brain barrier breakdown via urea-activated matrix metalloproteinase-2 and insolubility of tau protein. Aging 2023, 15, 10972–10995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Exposure/Condition | Outcome | Study Model | Evidence Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pi additives intake | ↑ BP (positive association) | Human | Indirect |

| High Pi intake | ↑ BP | Human | Direct |

| High Pi diet | ↑ BP | Mouse/Rat | Direct |

| High Pi diet | ↑ SNA and ↑ BP responses | Rat | Direct |

| Circulating FGF23 levels | ↑ BP (positive association) | Human | Indirect |

| High Pi diet | ↑ circulating and brain FGF23 levels | Rat | Direct |

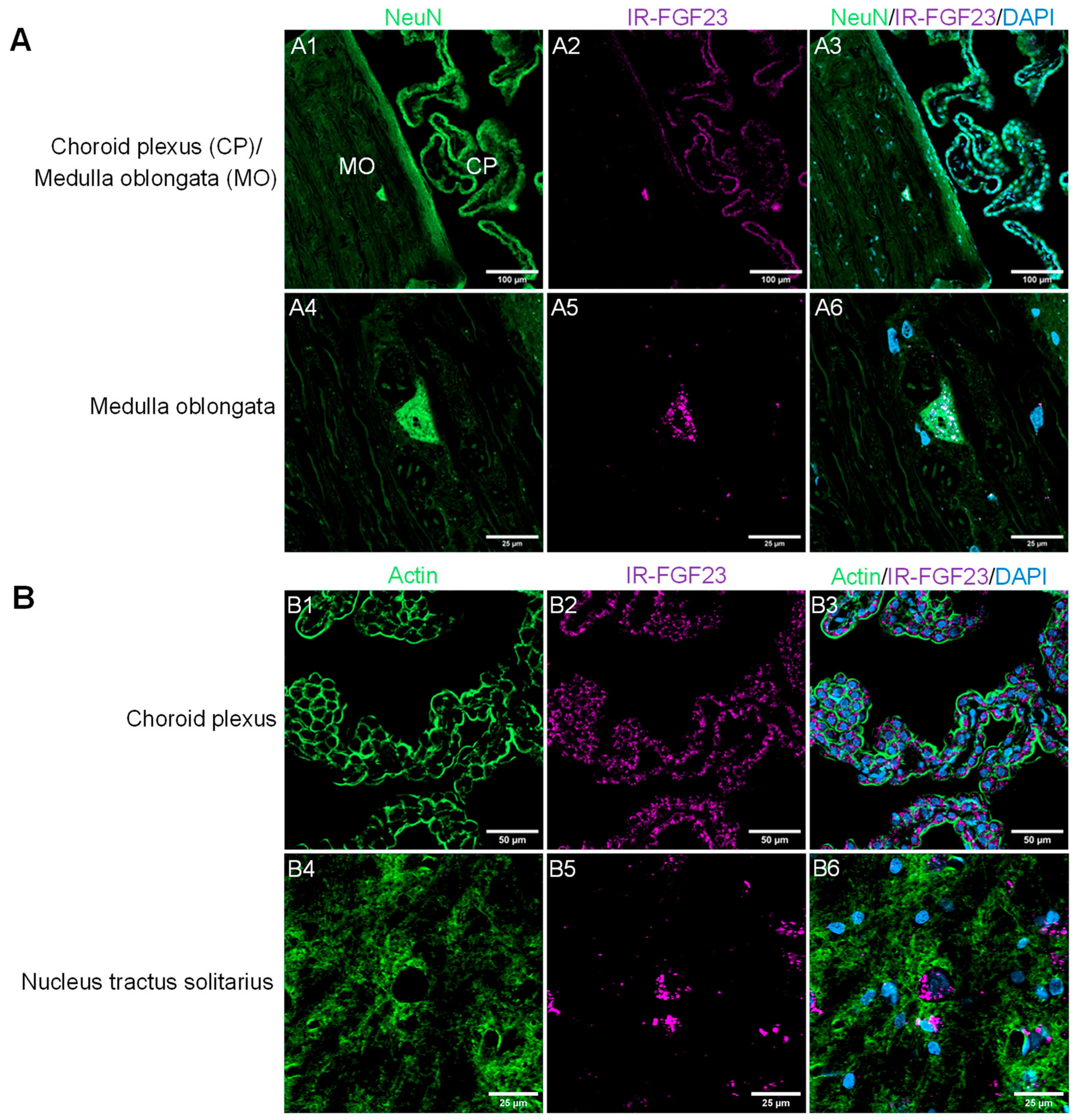

| IV labeled FGF23 | Detected in the choroid plexus and brainstem regions | Rat | Direct |

| ICV FGF23 injection | ↑ SNA and ↑ BP | Rat | Direct |

| ICV FGFR4 inhibitor * | ↓ SNA and ↓ BP responses | Rat | Direct |

| ICV calcineurin inhibitor * | ↓ SNA and ↓ BP responses | Rat | Direct |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, H.-K.; Moe, O.W.; Vongpatanasin, W. High-Phosphate-Induced Hypertension: The Pathogenic Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23) Signaling in Sympathetic Nervous System Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031138

Kim H-K, Moe OW, Vongpatanasin W. High-Phosphate-Induced Hypertension: The Pathogenic Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23) Signaling in Sympathetic Nervous System Activation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031138

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Han-Kyul, Orson W. Moe, and Wanpen Vongpatanasin. 2026. "High-Phosphate-Induced Hypertension: The Pathogenic Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23) Signaling in Sympathetic Nervous System Activation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031138

APA StyleKim, H.-K., Moe, O. W., & Vongpatanasin, W. (2026). High-Phosphate-Induced Hypertension: The Pathogenic Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 (FGF23) Signaling in Sympathetic Nervous System Activation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031138