Integrative Proteomics of Extracellular Vesicles from hiPSC-Derived Cardiac Organoids Reveals Heart Tissue-like Molecular Representativity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

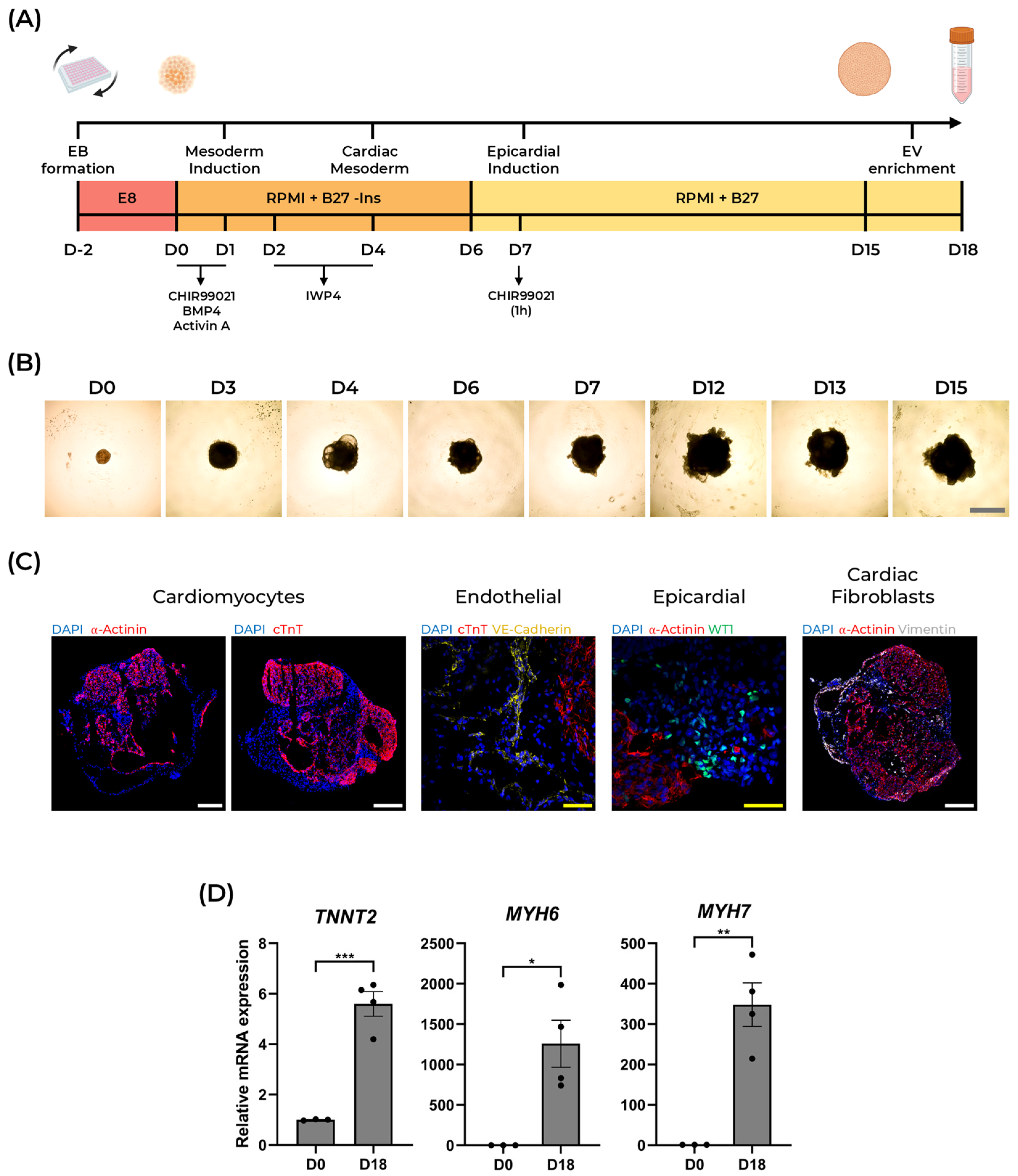

2.1. Generation of Human Cardioids from hiPSCs

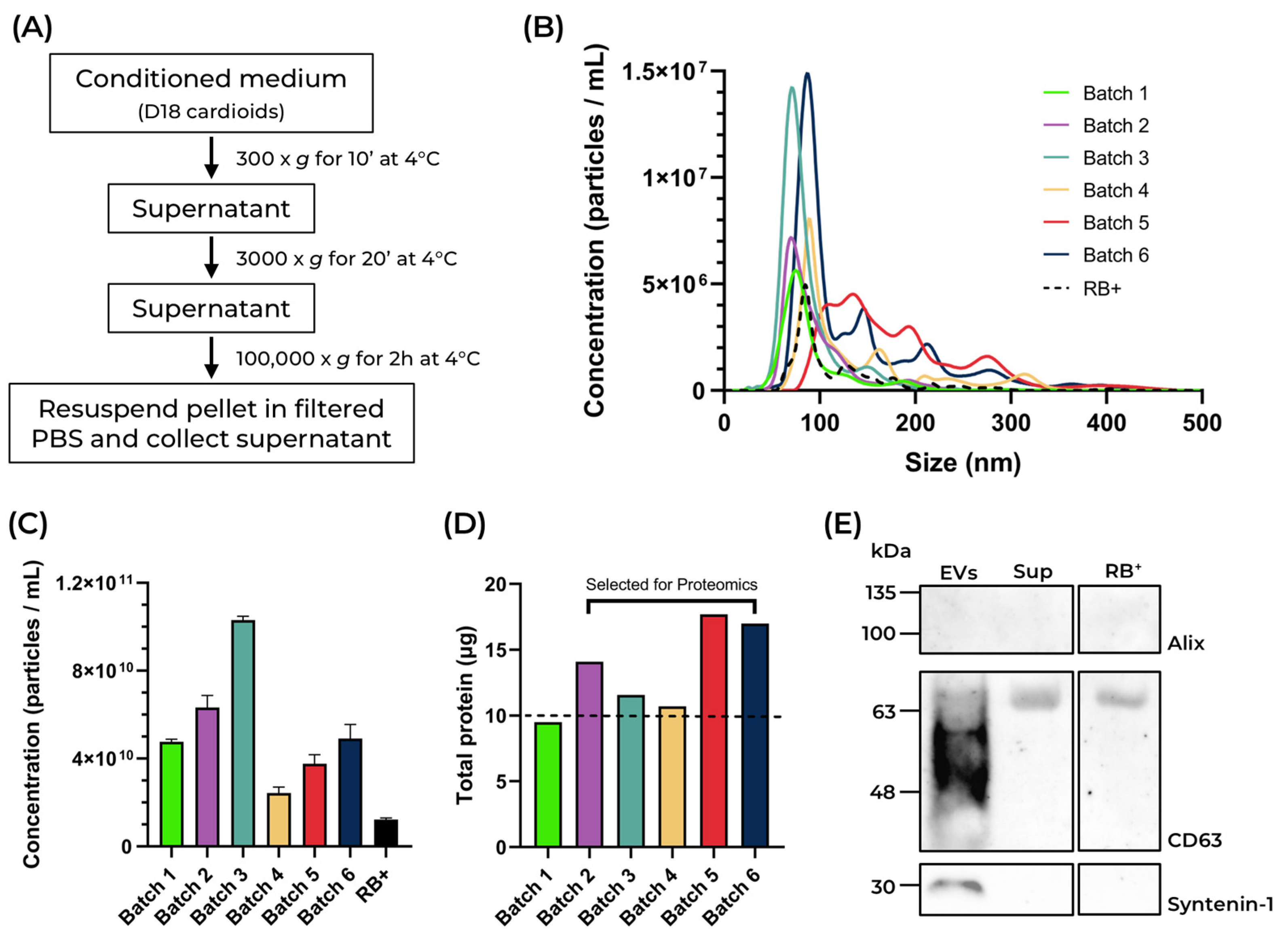

2.2. Isolation and Characterization of Cardioid-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (cardEVs)

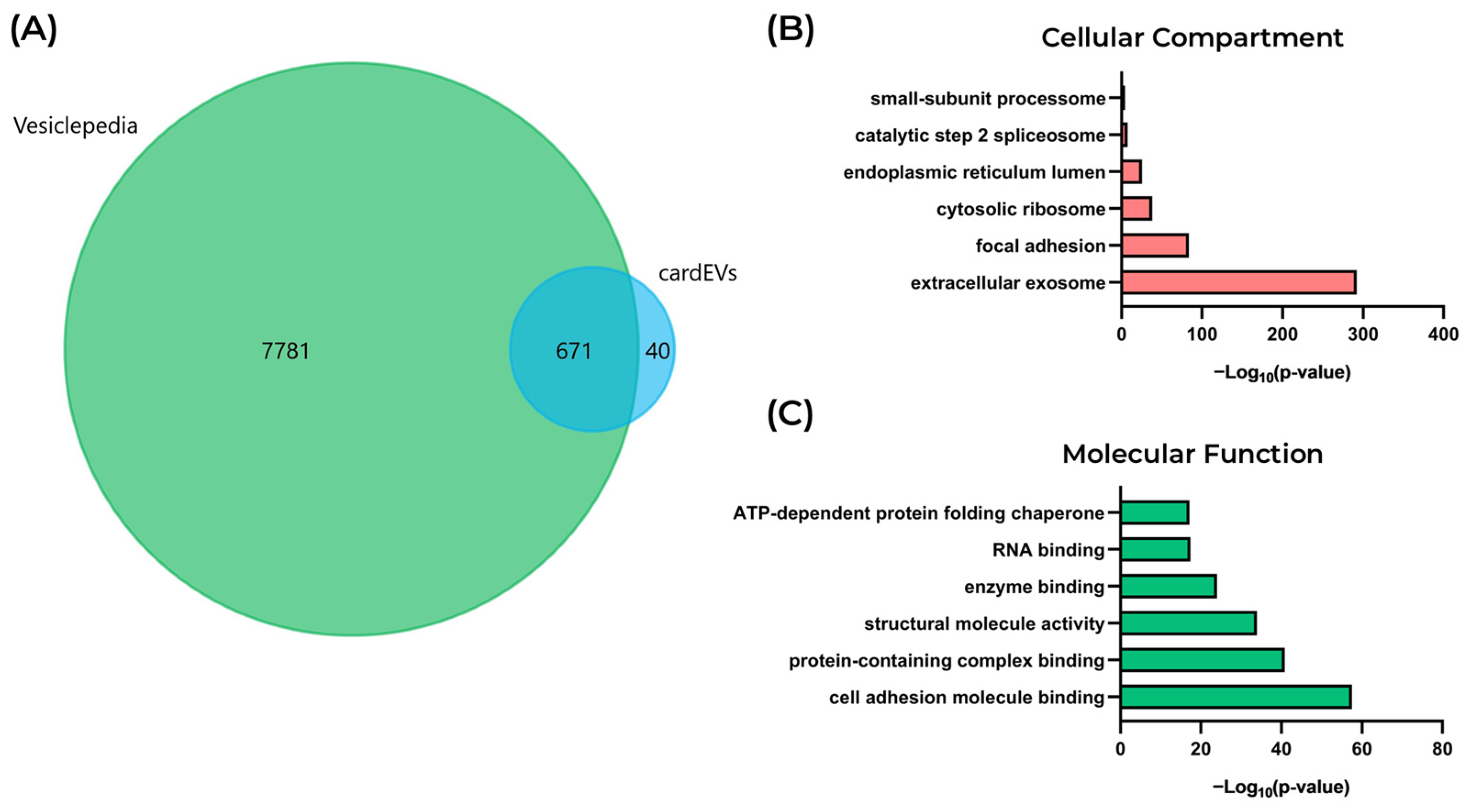

2.3. Proteomic and Functional Profiling of cardEVs

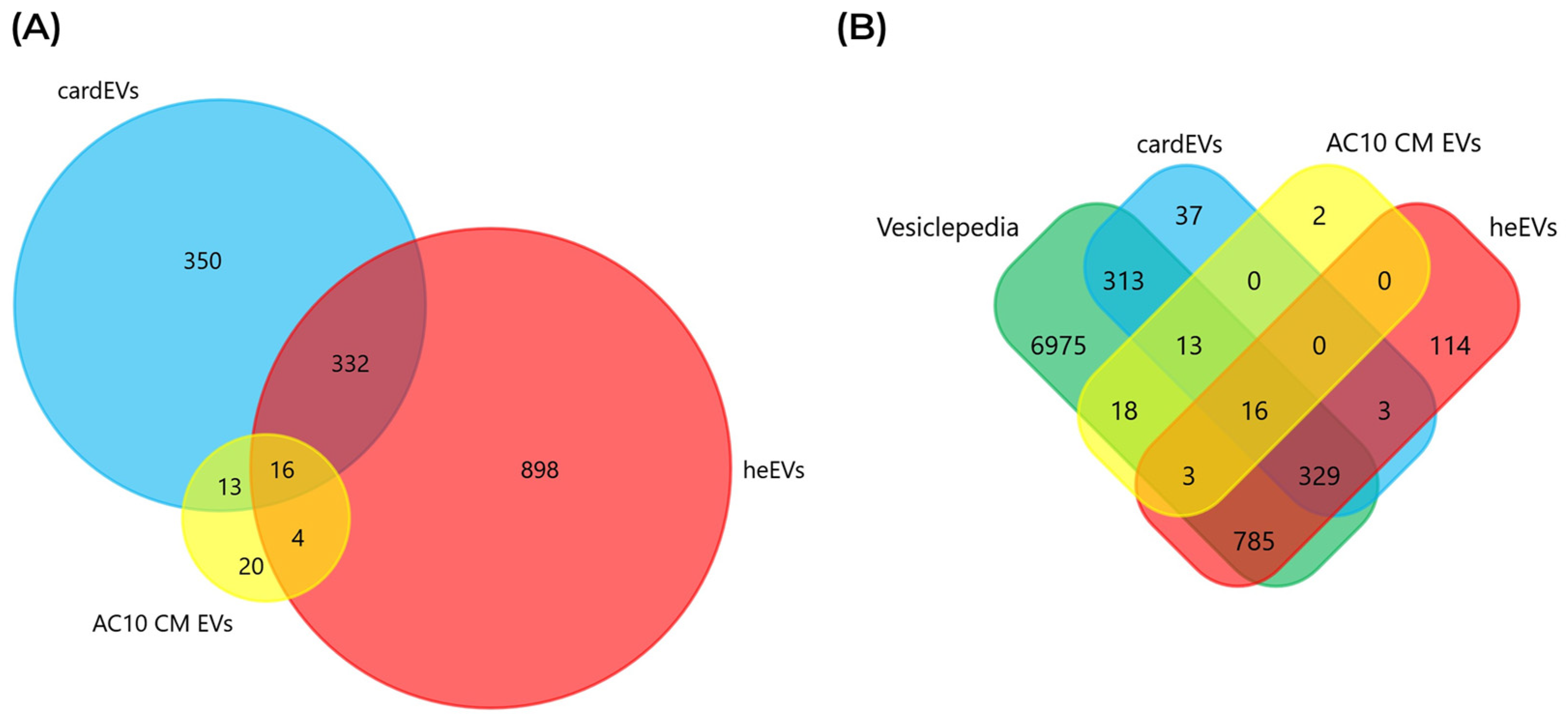

2.4. Comparing the Protein Cargo of cardEVs with Other Sources of Cardiac EVs

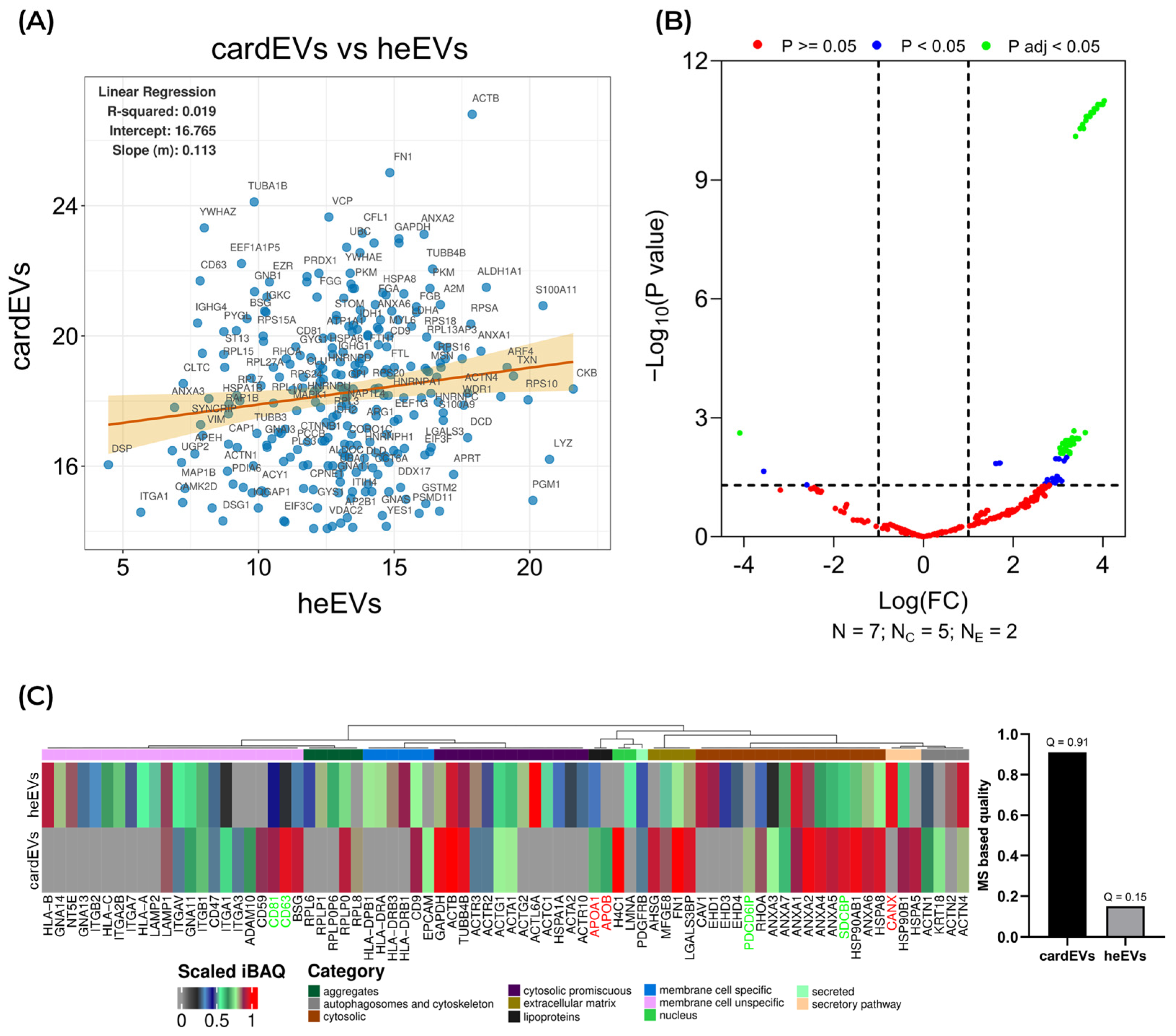

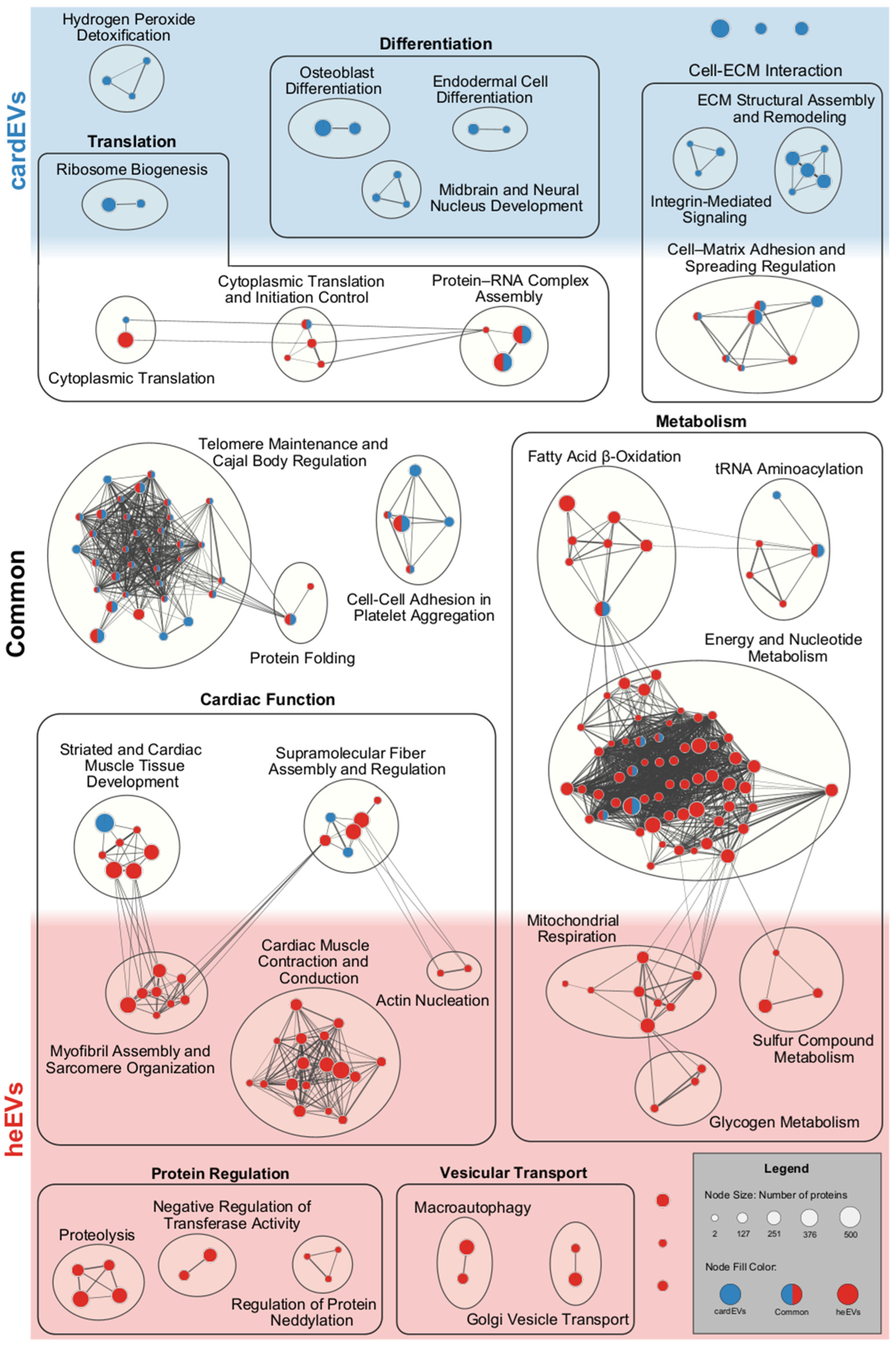

2.5. Comparison Between cardEVs and heEVs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cell Culture

3.2. Differentiation of 3D Self-Assembling Cadioids

3.3. Cardioid Sectioning and Immunofluorescence

3.4. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

3.5. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles by Differential Ultracentrifugation

3.6. Western Blot

3.7. Peptide Preparation and LC-MS/MS Analysis

3.8. Analysis of Proteomics Data

3.9. Functional and Protein Interaction Analyses of the EV Cargoes of cardEVs and heEVs

3.10. Statistics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| hiPSCs | Human induced pluripotent stem cells |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| cardEVs | EVs isolated from human cardioids |

| heEVs | EVs isolated from human heart explants of cadaveric donors |

| AC10 CM EVs | EVs isolated from the AC10 cardiomyocyte cell line |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| iBAQ | Intensity-based absolute quantification |

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, B.; Jayabaskaran, J.; Jauhari, S.M.; Chan, S.P.; Goh, R.; Kueh, M.T.W.; Li, H.; Chin, Y.H.; Kong, G.; Anand, V.V.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases: Projections from 2025 to 2050. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Samtani, R.; Dhanantwari, P.; Lee, E.; Yamada, S.; Shiota, K.; Donofrio, M.T.; Leatherbury, L.; Lo, C.W. A Detailed Comparison of Mouse and Human Cardiac Development. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 76, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.G.; Kho, C.; Hajjar, R.J.; Ishikawa, K. Experimental Models of Cardiac Physiology and Pathology. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019, 24, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakrou, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Greenland, G.V.; Simsek, B.; Hebl, V.B.; Guan, Y.; Woldemichael, K.; Talbot, C.C.; Aon, M.A.; et al. Differences in Molecular Phenotype in Mouse and Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Scheidt, M.; Zhao, Y.; Kurt, Z.; Pan, C.; Zeng, L.; Yang, X.; Schunkert, H.; Lusis, A.J. Applications and Limitations of Mouse Models for Understanding Human Atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.S.; Shin, H.H.; Shudo, Y. Current Status and Limitations of Myocardial Infarction Large Animal Models in Cardiovascular Translational Research. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 673683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakikes, I.; Ameen, M.; Termglinchan, V.; Wu, J.C. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes: Insights into Molecular, Cellular, and Functional Phenotypes. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lei, W.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Shen, Z.; et al. Generation of Human Vascularized and Chambered Cardiac Organoids for Cardiac Disease Modelling and Drug Evaluation. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.A.; Dias, T.P.; Cabral, J.M.S.; Pinto-do-Ó, P.; Diogo, M.M. Human Multilineage Pro-Epicardium/Foregut Organoids Support the Development of an Epicardium/Myocardium Organoid. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.B.; Zawada, D.; De Angelis, M.T.; Martens, L.D.; Santamaria, G.; Zengerle, S.; Nowak-Imialek, M.; Kornherr, J.; Zhang, F.; Tian, Q.; et al. Epicardioid Single-Cell Genomics Uncovers Principles of Human Epicardium Biology in Heart Development and Disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Israeli, Y.R.; Wasserman, A.H.; Gabalski, M.A.; Volmert, B.D.; Ming, Y.; Ball, K.A.; Yang, W.; Zou, J.; Ni, G.; Pajares, N.; et al. Self-Assembling Human Heart Organoids for the Modeling of Cardiac Development and Congenital Heart Disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, T.; Ge, Y.; Wan, X.; Liang, G. Cardiac Organoids: A 3D Technology for Disease Modeling and Drug Screening. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 4987–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yin, J.; Hao, Y.; Gao, W.; Li, Q.; Feng, Q.; Tao, B.; Hao, M.; Liu, Y.; Lin, C.; et al. Single-Cell Sequencing and Organoids: Applications in Organ Development and Disease. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maacha, S.; Bhat, A.A.; Jimenez, L.; Raza, A.; Haris, M.; Uddin, S.; Grivel, J.C. Extracellular Vesicles-Mediated Intercellular Communication: Roles in the Tumor Microenvironment and Anti-Cancer Drug Resistance. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A.C.; Dawson, T.R.; Di Vizio, D.; Weaver, A.M. Context-Specific Regulation of Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Cargo Selection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, K.; Staufer, O. Membranes on the Move: The Functional Role of the Extracellular Vesicle Membrane for Contact-Dependent Cellular Signalling. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadami, S.; Dellinger, K. The Lipid Composition of Extracellular Vesicles: Applications in Diagnostics and Therapeutic Delivery. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1198044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pando, A.; Schorl, C.; Fast, L.D.; Reagan, J.L. Tumor Derived Extracellular Vesicles Modulate Gene Expression in T Cells. Gene 2023, 850, 146920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Gao, L.; Rudebush, T.L.; Yu, L.; Zucker, I.H. Extracellular Vesicles Regulate Sympatho-Excitation by Nrf2 in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Hu, G.; Gao, L.; Hackfort, B.T.; Zucker, I.H. Extracellular Vesicular MicroRNA-27a* Contributes to Cardiac Hypertrophy in Chronic Heart Failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 143, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, T.; Nishimura, T.; Kawana, H.; Hirosawa, K.M.; Yamakawa, R.; Sapili, H.; Oono-Yakura, K.; Nakagawa, R.; Inoue, T.; Nureki, O.; et al. Efficient Cellular Transformation via Protein Delivery through the Protrusion-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.G.; Lee, P.; Gordon, R.E.; Sahoo, S.; Kho, C.; Jeong, D. Analysis of Extracellular Vesicle MiRNA Profiles in Heart Failure. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 7214–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Campo, C.V.; Liaw, N.Y.; Gunadasa-Rohling, M.; Matthaei, M.; Braga, L.; Kennedy, T.; Salinas, G.; Voigt, N.; Giacca, M.; Zimmermann, W.H.; et al. Regenerative Potential of Epicardium-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Mediated by Conserved MiRNA Transfer. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Knowlton, A.A. HSP60 Trafficking in Adult Cardiac Myocytes: Role of the Exosomal Pathway. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, H3052–H3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Deng, L.; Wang, D.; Li, N.; Chen, X.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, J.; Gao, X.; Liao, M.; Wang, M.; et al. Mechanism of TNF-α Autocrine Effects in Hypoxic Cardiomyocytes: Initiated by Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1α, Presented by Exosomes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 53, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, N.A.; Moncayo-Arlandi, J.; Sepulveda, P.; Diez-Juan, A. Cardiomyocyte Exosomes Regulate Glycolytic Flux in Endothelium by Direct Transfer of GLUT Transporters and Glycolytic Enzymes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 109, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura, S.; Gámez-Valero, A.; Lupón, J.; Gálvez-Montón, C.; Borràs, F.E.; Bayes-Genis, A. Proteomic Signature of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Lab. Investig. 2018, 98, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Correction in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornberg, R.D. Chromatin Structure: A Repeating Unit of Histones and DNA. Science 1974, 184, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, A.J.; Korb, E. The ABCs of the H2Bs: The Histone H2B Sequences, Variants, and Modifications. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Zambrano, G.; Burton, A.; Bannister, A.J.; Schneider, R. Histone Post-Translational Modifications—Cause and Consequence of Genome Function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanam, J.; Chetty, V.K.; Anchan, S.; Reetz, L.; Yang, Q.; Rideau, E.; Liu, X.; Lieberwirth, I.; Wrobeln, A.; Hoyer, P.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Transfer Chromatin-like Structures That Induce Non-Mutational Dysfunction of P53 in Bone Marrow Stem Cells. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lázaro-Ibáñez, E.; Lässer, C.; Shelke, G.V.; Crescitelli, R.; Jang, S.C.; Cvjetkovic, A.; García-Rodríguez, A.; Lötvall, J. DNA Analysis of Low- and High-Density Fractions Defines Heterogeneous Subpopulations of Small Extracellular Vesicles Based on Their DNA Cargo and Topology. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1656993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Fredriksson Sundbom, M.; Muthukrishnan, U.; Natarajan, B.; Stransky, S.; Görgens, A.; Nordin, J.Z.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Sandblad, L.; Sidoli, S.; et al. Extracellular Histones as Exosome Membrane Proteins Regulated by Cell Stress. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.V. The Actin Cytoskeleton. Electron. Microsc. Rev. 1988, 1, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwarek-Maruszewska, A.; Hotulainen, P.; Mattila, P.K.; Lappalainen, P. Contractility-Dependent Actin Dynamics in Cardiomyocyte Sarcomeres. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, R.A. Fibronectin: A Brief Overview of Its Structure, Function, and Physiology. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1987, 9, S317–S321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollinger, A.J.; Smith, M.L. Fibronectin, the Extracellular Glue. Matrix Biol. 2017, 60–61, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingoglia, G.; Sag, C.M.; Rex, N.; De Franceschi, L.; Vinchi, F.; Cimino, J.; Petrillo, S.; Wagner, S.; Kreitmeier, K.; Silengo, L.; et al. Hemopexin Counteracts Systolic Dysfunction Induced by Heme-Driven Oxidative Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 108, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, C.; Deng, J.; Luo, S. Double-Edged Functions of Hemopexin in Hematological Related Diseases: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Application. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1274333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhal-Littleton, S. Mechanisms of Cardiac Iron Homeostasis and Their Importance to Heart Function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 133, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szablewski, L. Glucose Transporters in Healthy Heart and in Cardiac Disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 230, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woulfe, K.C.; Sucharov, C.C. Midkine’s Role in Cardiac Pathology. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2017, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graifer, D.; Malygin, A.; Shefer, A.; Tamkovich, S. Ribosomal Proteins as Exosomal Cargo: Random Passengers or Crucial Players in Carcinogenesis? Adv. Biol. 2025, 9, 2400360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochkasova, A.; Arbuzov, G.; Malygin, A.; Graifer, D. Two “Edges” in Our Knowledge on the Functions of Ribosomal Proteins: The Revealed Contributions of Their Regions to Translation Mechanisms and the Issues of Their Extracellular Transport by Exosomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valášek, L.S.; Zeman, J.; Wagner, S.; Beznosková, P.; Pavlíková, Z.; Mohammad, M.P.; Hronová, V.; Herrmannová, A.; Hashem, Y.; Gunišová, S. Embraced by EIF3: Structural and Functional Insights into the Roles of EIF3 across the Translation Cycle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 10948–10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, S.K.; Wong, S.W.K.; Yeung, C.L.S.; Li, J.Y.K.; Mao, X.; Chung, C.Y.S.; Yam, J.W.P. Liver Cancer Cells with Nuclear MET Overexpression Release Translation Regulatory Protein-Enriched Extracellular Vesicles Exhibit Metastasis Promoting Activity. J. Extracell. Biol. 2022, 1, e39, Correction in J. Extracell. Biol. 2025, 4, e70070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbah, M.; Lishner, M.; Jarchowsky-Dolberg, O.; Tartakover-Matalon, S.; Brin, Y.S.; Pasmanik-Chor, M.; Neumann, A.; Drucker, L. Ribosomal Proteins as Distinct “Passengers” of Microvesicles: New Semantics in Myeloma and Mesenchymal Stem Cells’ Communication. Transl. Res. 2021, 236, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neve, A.; Cantatore, F.P.; Maruotti, N.; Corrado, A.; Ribatti, D. Extracellular Matrix Modulates Angiogenesis in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 756078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinand, C.S.; Raju, R.; Soumya, S.J.; Arya, P.S.; Sudhakaran, P.R. VEGF-A/VEGFR2 Signaling Network in Endothelial Cells Relevant to Angiogenesis. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 10, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arderiu, G.; Peña, E.; Badimon, L. Angiogenic Microvascular Endothelial Cells Release Microparticles Rich in Tissue Factor That Promotes Postischemic Collateral Vessel Formation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Pang, H.; Wu, H.; Peng, X.; Tan, Q.; Lin, S.; Wei, B. CCL2 Promotes Proliferation, Migration and Angiogenesis through the MAPK/ERK1/2/MMP9, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/Β-catenin Signaling Pathways in HUVECs. Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 25, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateeq, M.; Broadwin, M.; Sellke, F.W.; Abid, M.R. Extracellular Vesicles’ Role in Angiogenesis and Altering Angiogenic Signaling. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohela, M.; Bry, M.; Tammela, T.; Alitalo, K. VEGFs and Receptors Involved in Angiogenesis versus Lymphangiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, M.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Signal Transduction by VEGF Receptors in Regulation of Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wörsdörfer, P.; Ergün, S. The Impact of Oxygen Availability and Multilineage Communication on Organoid Maturation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 35, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ontoria-Oviedo, I.; Dorronsoro, A.; Sánchez, R.; Ciria, M.; Gómez-Ferrer, M.; Buigues, M.; Grueso, E.; Tejedor, S.; García-García, F.; González-King, H.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Hypoxic AC10 Cardiomyocytes Modulate Fibroblast Cell Motility. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitolis, A.; Suss, P.H.; Roderjan, J.G.; Angulski, A.B.B.; da Costa, F.D.A.; Stimamiglio, M.A.; Correa, A. Human Heart Explant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Characterization and Effects on the In Vitro Recellularization of Decellularized Heart Valves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pan, W. The Biological Role of the Collagen Alpha-3 (VI) Chain and Its Cleaved C5 Domain Fragment Endotrophin in Cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 5779–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.B.; Cosson, M.V.; Tsansizi, L.I.; Holmes, T.L.; Gilmore, T.; Hampton, K.; Song, O.R.; Vo, N.T.N.; Nasir, A.; Chabronova, A.; et al. Perlecan (HSPG2) Promotes Structural, Contractile, and Metabolic Development of Human Cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaksonen, M.; Roux, A. Mechanisms of Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linial, M.; Miller, K.; Scheller, R.H. VAT 1: An Abundant Membrane Protein from Torpedo Cholinergic Synaptic Vesicles. Neuron 1989, 2, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, H.; Andreu, Z.; Mazzeo, C.; Toribio, V.; Pérez-Rivera, A.E.; López-Martín, S.; García-Silva, S.; Hurtado, B.; Morato, E.; Peláez, L.; et al. CD9 Inhibition Reveals a Functional Connection of Extracellular Vesicle Secretion with Mitophagy in Melanoma Cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Seo, E.C.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Hwangbo, C. The Multifunctional Protein Syntenin-1: Regulator of Exosome Biogenesis, Cellular Function, and Tumor Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Lei, Q.Y.; Zhao, S.; Guan, K.L. Regulation of Glycolysis and Gluconeogenesis by Acetylation of PKM and PEPCK. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2011, 76, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkoftaki, G.; Chen, Y.; Han, M.; Sandoval, M.; Yu, X.; Zhao, H.; Orlicky, D.J.; Thompson, D.C.; Vasiliou, V. Transcriptomic Analysis and Plasma Metabolomics in Aldh16a1-Null Mice Reveals a Potential Role of ALDH16A1 in Renal Function. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2017, 276, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, C.; Németh, J.; Angel, P.; Hess, J. S100A8 and S100A9 in Inflammation and Cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 1622–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Halawani, A.; Mithieux, S.M.; Yeo, G.C.; Hosseini-Beheshti, E.; Weiss, A.S. Extracellular Vesicles: Interplay with the Extracellular Matrix and Modulated Cell Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Sluijter, J.P.G. Extracellular Vesicles in Cardiovascular Homeostasis and Disease: Potential Role in Diagnosis and Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudsari, H.K.; O’Hern, C.; Ural, E.; Damrath, M.; Neeb, E.; Zoofaghari, M.; Veletić, M.; Louch, W.E.; Aguirre, A.; Balasingham, I.; et al. Human Heart Organoid-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Cardiac Intercellular Communication. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Nanoscale Computing and Communication, Coventry, UK, 20–22 September 2023; Volume 7, pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Holden, P.; Hansen, U. The Expanded Collagen VI Family: New Chains and New Questions. Connect. Tissue Res. 2013, 54, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzin, S.; Timis, E.; Doliana, R.; Mongiat, M.; Spessotto, P. “Unraveling EMILIN-1: A Multifunctional ECM Protein with Tumor-Suppressive Roles” Mechanistic Insights into Cancer Protection Through Signaling Modulation and Lymphangiogenesis Control. Cells 2025, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, A.; Blobe, G.C. The Role of the Extracellular Matrix Protein TGFBI in Cancer. Cell. Signal. 2021, 84, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, M. Apolipoprotein B Levels, APOB Alleles, and Risk of Ischemic Cardiovascular Disease in the General Population, a Review. Atherosclerosis 2009, 206, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Her, C. Inhibition of Topoisomerase (DNA) I (TOP1): DNA Damage Repair and Anticancer Therapy. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1652–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavali, S.S.; Carman, P.J.; Shuman, H.; Ostap, E.M.; Sindelar, C.V. High-Resolution Structures of Myosin-IC Reveal a Unique Actin-Binding Orientation, ADP Release Pathway, and Power Stroke Trajectory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2415457122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.W.; Dong, K.; Zhang, H.Z. The Roles of CD73 in Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 460654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vega, S.; Iwamoto, T.; Yamada, Y. Fibulins: Multiple Roles in Matrix Structures and Tissue Functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1890–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauzá-Martinez, J.; Heck, A.J.R.; Wu, W. HLA-B and Cysteinylated Ligands Distinguish the Antigen Presentation Landscape of Extracellular Vesicles. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J.; Ramírez-Anguita, J.M.; Saüch-Pitarch, J.; Ronzano, F.; Centeno, E.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET Knowledge Platform for Disease Genomics: 2019 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.S.; Moraes, M.C.S.; Na, C.H.; Fierro-Monti, I.; Henriques, A.; Zahedi, S.; Bodo, C.; Tranfield, E.M.; Sousa, A.L.; Farinho, A.; et al. Is the Proteome of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Extracellular Vesicles a Marker of Advanced Lung Cancer? Cancers 2020, 12, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, S.N.; Rider, M.A.; Bundy, J.L.; Liu, X.; Singh, R.K.; Meckes, D.G., Jr. Proteomic Profiling of NCI-60 Extracellular Vesicles Uncovers Common Protein Cargo and Cancer Type-Specific Biomarkers. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 86999–87015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzan, A.L.; Nedeva, C.; Mathivanan, S. Extracellular Vesicles in Metabolism and Metabolic Diseases. In New Frontiers: Extracellular Vesicles; Subcellular Biochemistry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 97, pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, N.A.; Ontoria-Oviedo, I.; González-King, H.; Diez-Juan, A.; Sepúlveda, P. Glucose Starvation in Cardiomyocytes Enhances Exosome Secretion and Promotes Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.S.; Baeta, H.; Henriques, A.F.A.; Ejtehadifar, M.; Tranfield, E.M.; Sousa, A.L.; Farinho, A.; Silva, B.C.; Cabeçadas, J.; Gameiro, P.; et al. Proteomic Landscape of Extracellular Vesicles for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Subtyping. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.S.; Ribeiro, H.; Voabil, P.; Penque, D.; Jensen, O.N.; Molina, H.; Matthiesen, R. Global Mass Spectrometry and Transcriptomics Array Based Drug Profiling Provides Novel Insight into Glucosamine Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014, 13, 3294–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant Enables High Peptide Identification Rates, Individualized p.p.b.-Range Mass Accuracies and Proteome-Wide Protein Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, E.W.; Bandeira, N.; Sharma, V.; Perez-Riverol, Y.; Carver, J.J.; Kundu, D.J.; García-Seisdedos, D.; Jarnuczak, A.F.; Hewapathirana, S.; Pullman, B.S.; et al. The ProteomeXchange Consortium in 2020: Enabling ‘Big Data’ Approaches in Proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1145–D1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Csordas, A.; Bai, J.; Bernal-Llinares, M.; Hewapathirana, S.; Kundu, D.J.; Inuganti, A.; Griss, J.; Mayer, G.; Eisenacher, M.; et al. The PRIDE Database and Related Tools and Resources in 2019: Improving Support for Quantification Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D442–D450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | iBAQ | Function | Ref. | Present in Vesiclepedia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2BC8 | 181,341,427.50 | Component of the nucleosome | [31] | Yes |

| H3-3B | 136,707,625.00 | Component of the nucleosome | [31] | Yes |

| H4C1 | 126,990,328.75 | Component of the nucleosome | [31] | Yes |

| ACTB | 118,332,848.75 | Contributes to sarcomere formation and contractile function | [39,40] | Yes |

| H2AC14 | 61,760,312.50 | Component of the nucleosome | [31] | Yes |

| FN1 | 34,271,842.50 | ECM glycoprotein; mediates cell–matrix adhesion | [41,42] | Yes |

| HPX | 24,905,483.63 | Heme-binding protein | [43,44] | Yes |

| TF | 23,317,167.38 | Iron-binding transport protein | [45] | Yes |

| SLC2A3 | 22,775,432.50 | Glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) | [46] | Yes |

| MDK | 22,014,288.75 | Heparin-binding growth factor | [47] | Yes |

| Pathway | Source | Unique Genes | Similarity | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translation elongation and termination | Signor | 61/132 | 0.22 | 1.19 × 10−37 |

| Initiation of Translation | Signor | 55/113 | 0.21 | 1.47 × 10−35 |

| Cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins | WikiPathways | 47/88 | 0.21 | 9.84 × 10−33 |

| VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling | WikiPathways | 86/436 | 0.15 | 1.92 × 10−22 |

| Inducing angiogenesis | WikiPathways | 87/487 | 0.14 | 9.19 × 10−20 |

| β1-Integrin cell surface interaction | NCI PID | 31/65 | 0.13 | 1.65 × 10−19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vital, C.M.; Inácio, J.M.; Carvalho, A.S.; Beck, H.C.; Matthiesen, R.; Belo, J.A. Integrative Proteomics of Extracellular Vesicles from hiPSC-Derived Cardiac Organoids Reveals Heart Tissue-like Molecular Representativity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020981

Vital CM, Inácio JM, Carvalho AS, Beck HC, Matthiesen R, Belo JA. Integrative Proteomics of Extracellular Vesicles from hiPSC-Derived Cardiac Organoids Reveals Heart Tissue-like Molecular Representativity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020981

Chicago/Turabian StyleVital, Carlos Miguel, José Manuel Inácio, Ana Sofia Carvalho, Hans Christian Beck, Rune Matthiesen, and José António Belo. 2026. "Integrative Proteomics of Extracellular Vesicles from hiPSC-Derived Cardiac Organoids Reveals Heart Tissue-like Molecular Representativity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020981

APA StyleVital, C. M., Inácio, J. M., Carvalho, A. S., Beck, H. C., Matthiesen, R., & Belo, J. A. (2026). Integrative Proteomics of Extracellular Vesicles from hiPSC-Derived Cardiac Organoids Reveals Heart Tissue-like Molecular Representativity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020981