Impact of Mutations in the NCAPG and MSTN Genes on Body Composition, Structural Properties of Skeletal Muscle, Its Fatty Acid Composition, and Meat Quality of Bulls from a Charolais × Holstein F2 Cross

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

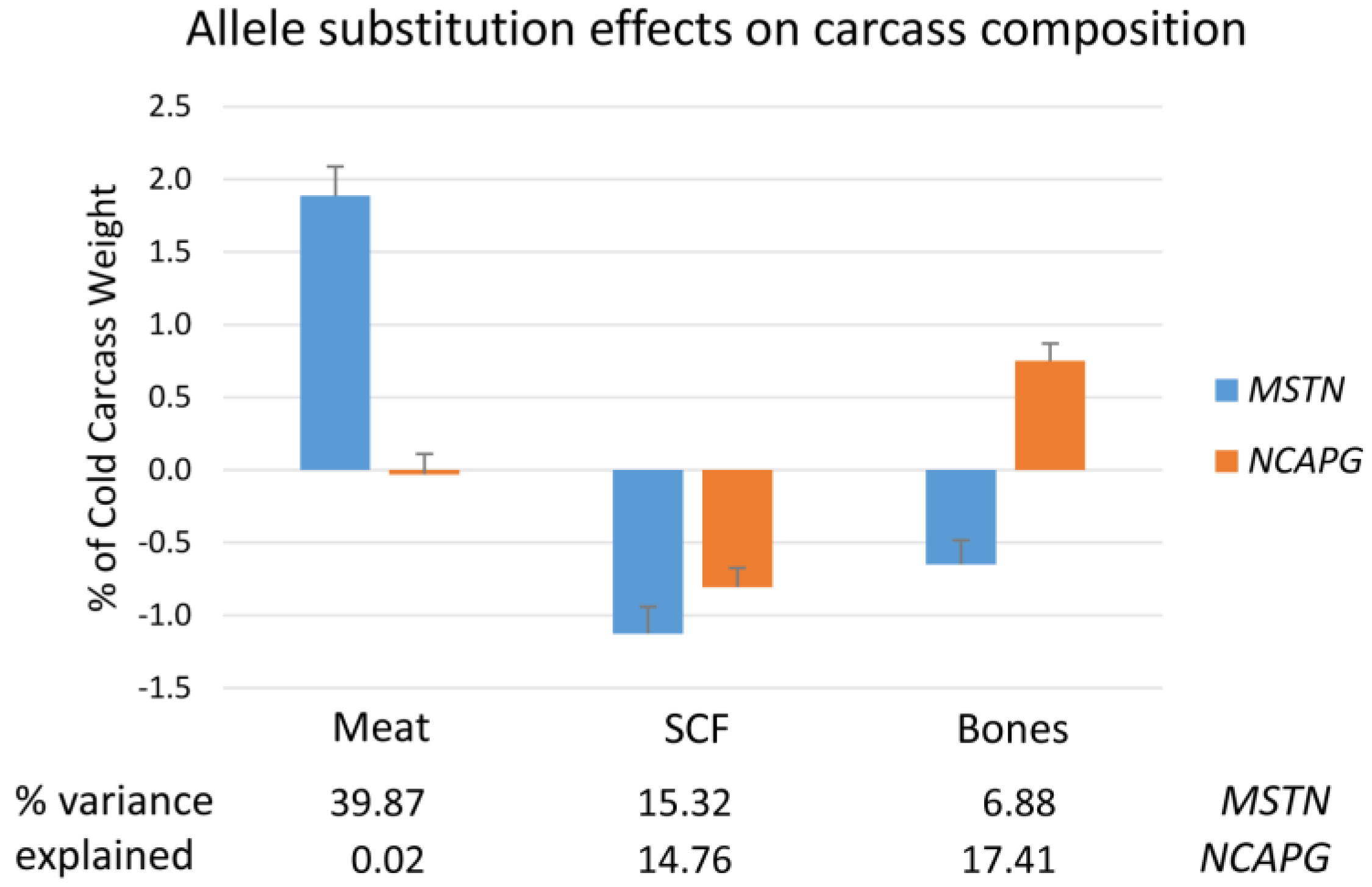

2.1. Weights and Carcass Composition

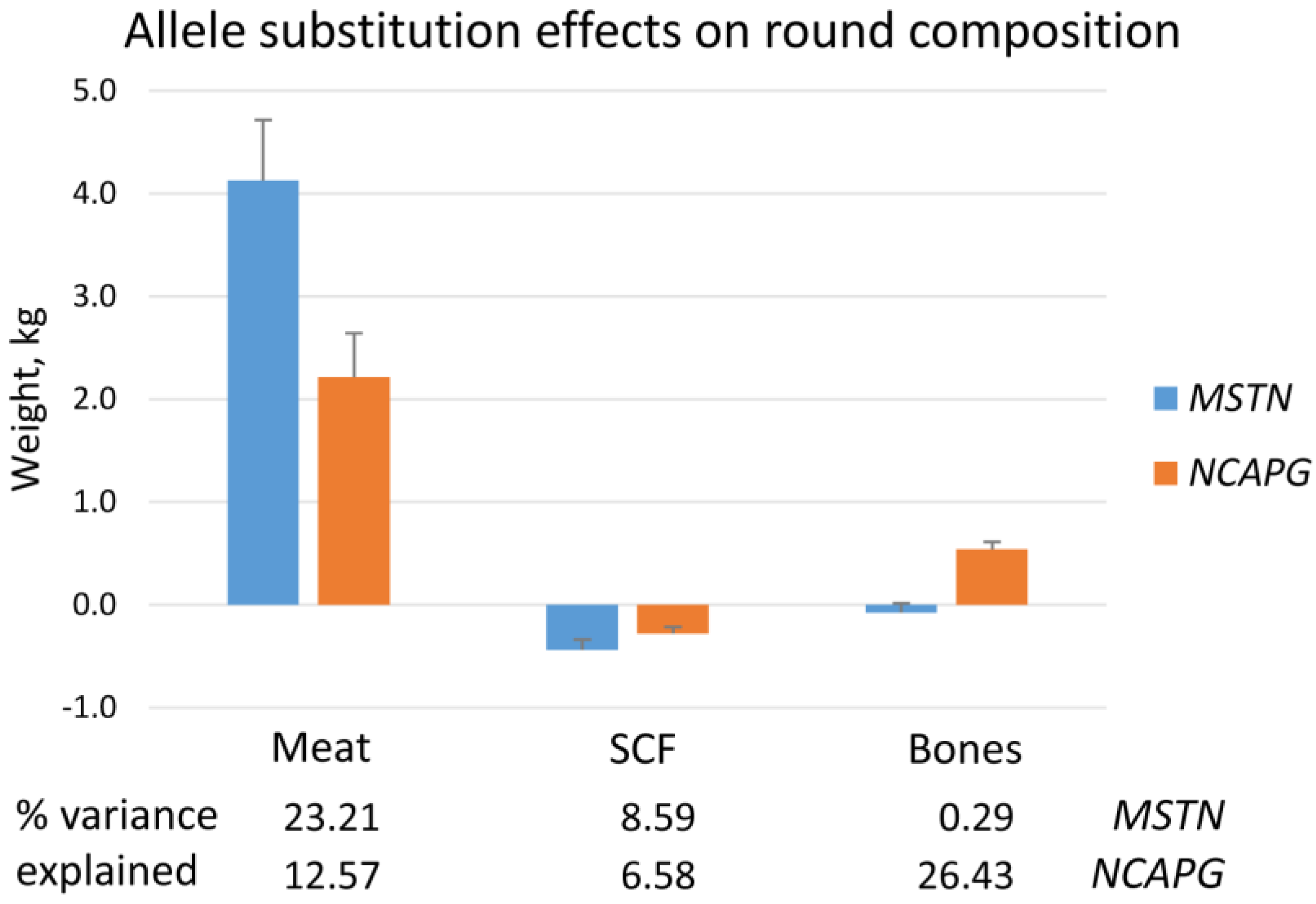

2.2. Dimensions, Weights, and Chemical Composition of Carcass Parts

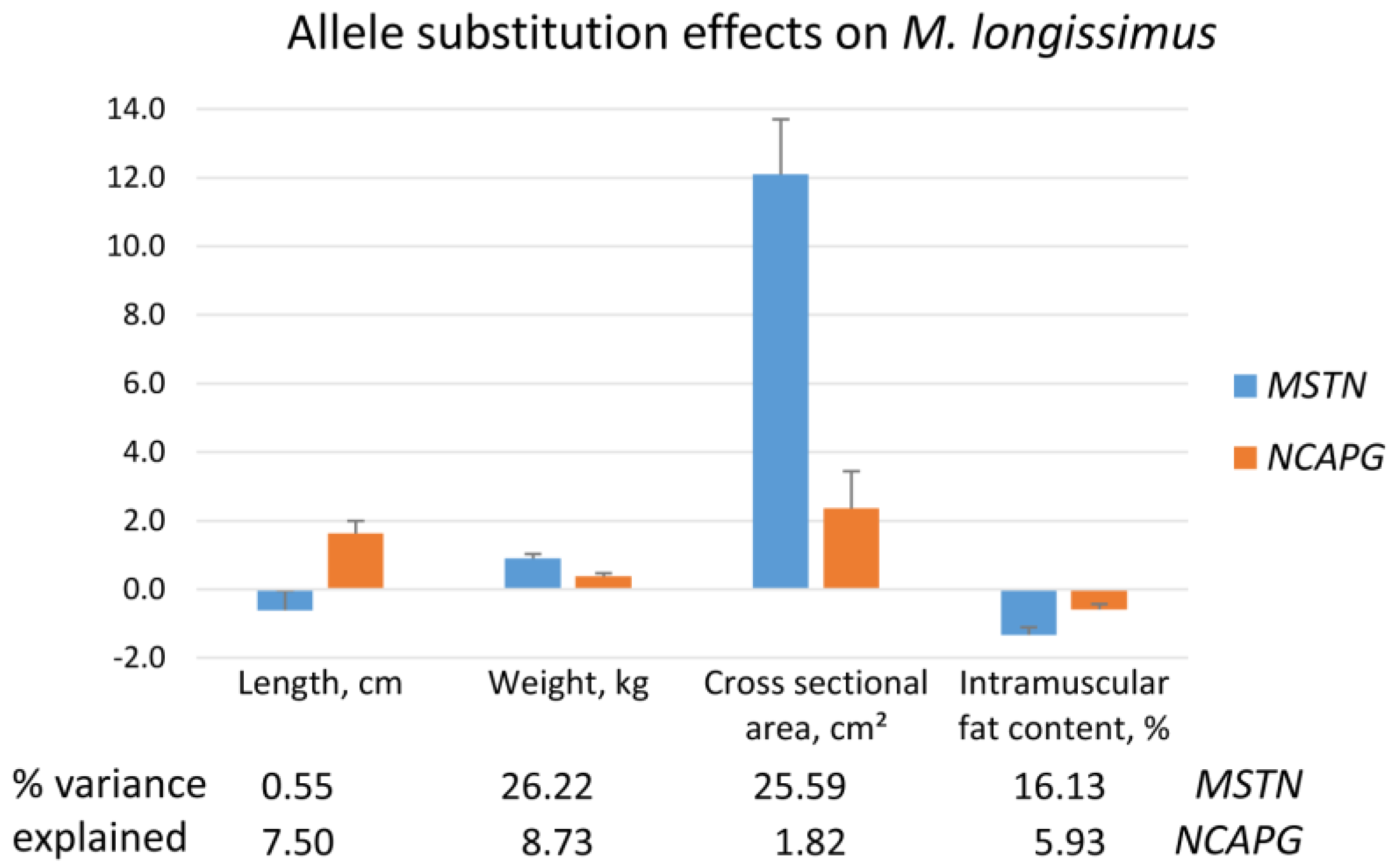

2.3. Muscle Traits and Meat Quality

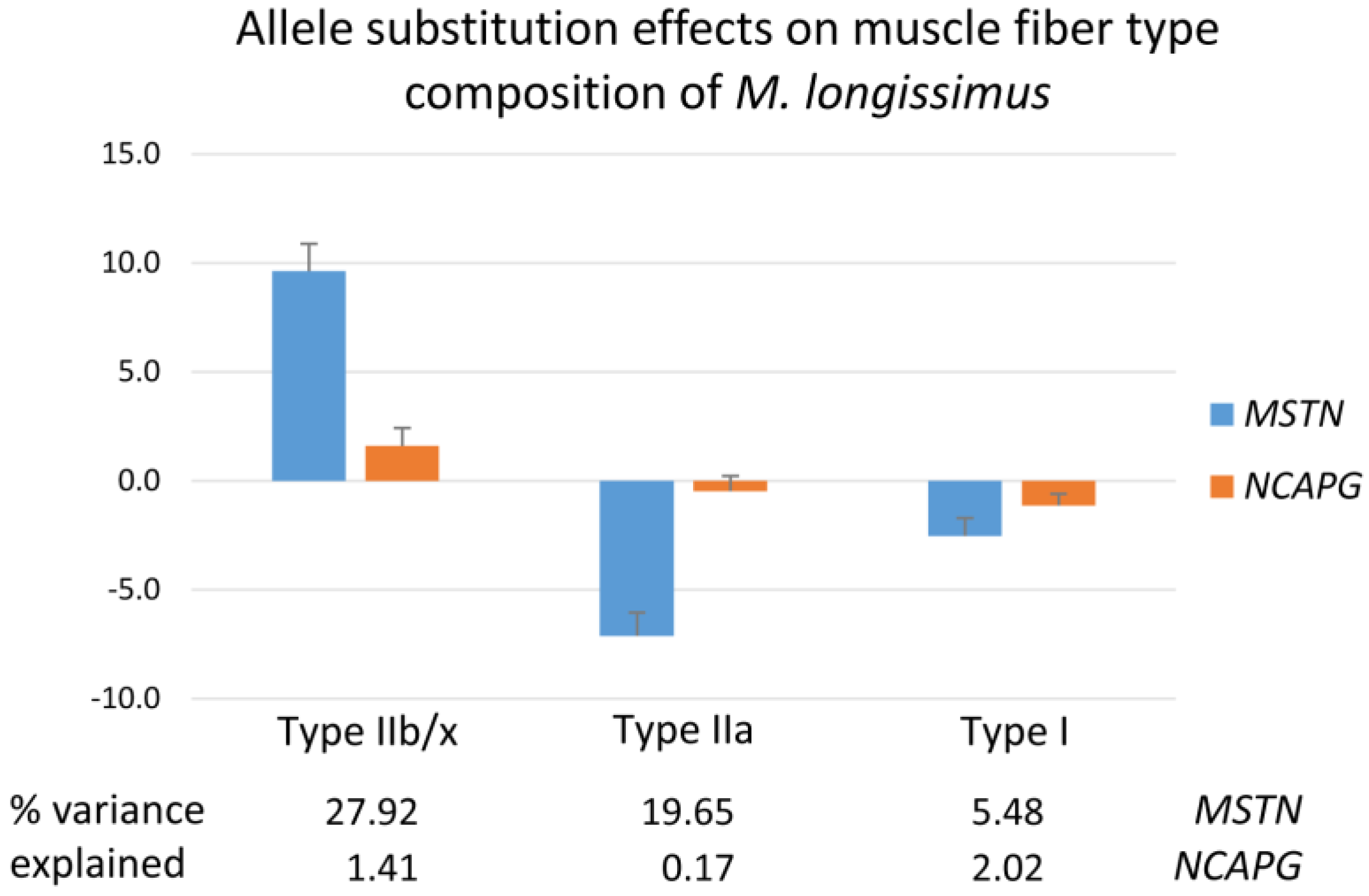

2.4. Cellular Structure of the M. longissimus

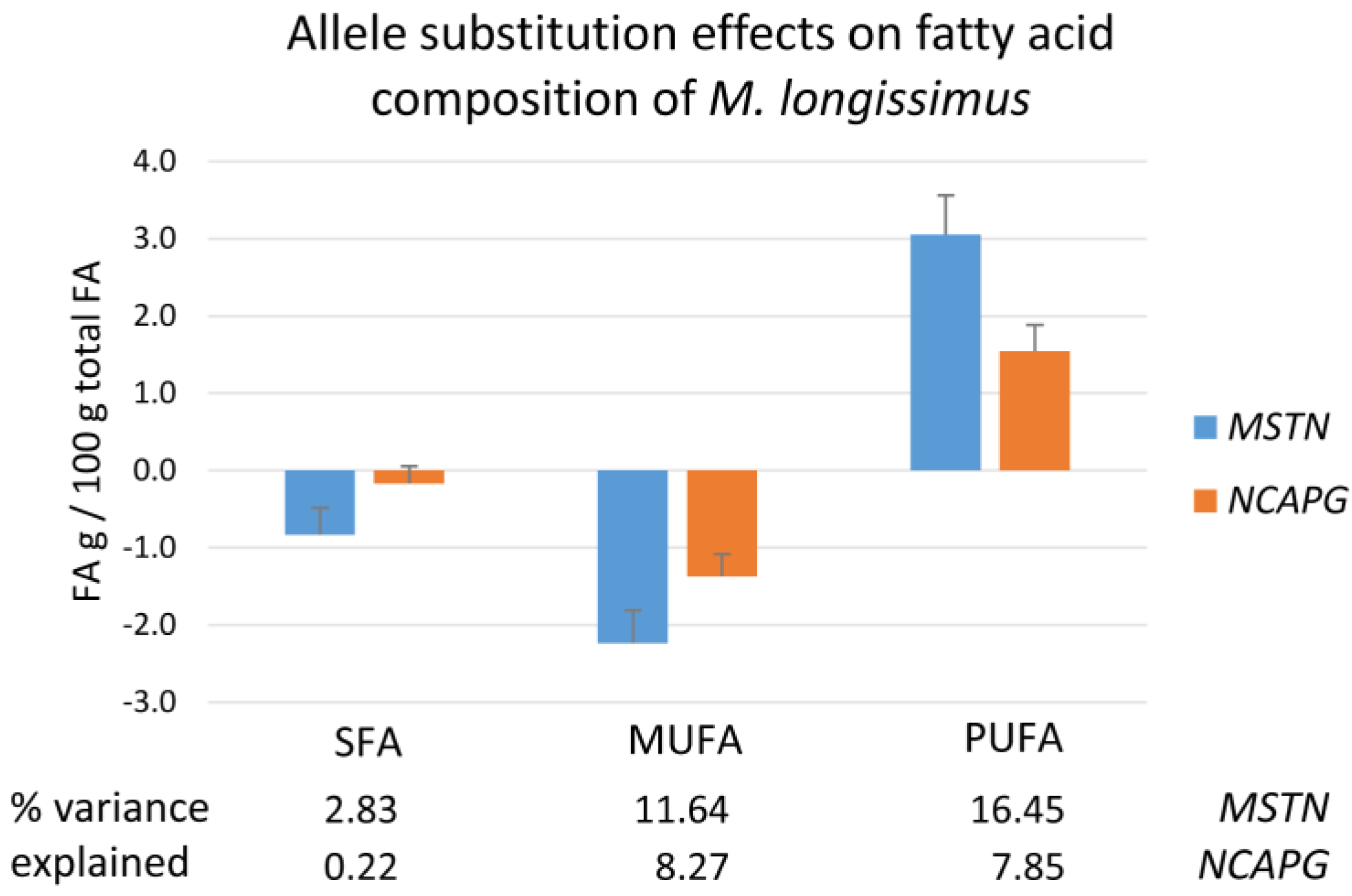

2.5. Fatty Acid Composition of the M. longissimus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Genotyping of the MSTN Q204X and NCAPG I442M Variants

4.3. Carcass Characteristics

4.4. Meat Quality

4.5. Muscle Structure

4.6. Fatty Acid Composition of M. longissimus

4.7. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCAPG | Non-SMC condensin I complex, subunit G |

| MSTN | Myostatin |

| FBN | Research Institute for Biology of Farm Animals |

| FLI | Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute |

| CH | Charolais |

| GH | German Holstein |

| GDF8 | Growth differentiation factor 8 |

| LCORL | Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor corepressor-like |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| QTN | Quantitative trait nucleotide |

| QTL | Quantitative trait locus |

| HCW | Hot carcass weight |

| CCW | Cold carcass weight |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| SE | Standard error |

| SCF | Subcutaneous fat |

| M. semitendinosus | Musculus semitendinosus |

| M. longissimus | Musculus longissimus dorsi |

| IMF | Intramuscular fat |

| CSA | Cross-sectional area |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acids |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| MEF2C | Myogenic transcription factor 2C |

| SCD5 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 5 |

| MYOD1 | Myogenic differentiation 1 |

| CREB1 | cAMP response element-binding protein 1 |

| PALI2 | PRC2-associated LCORL isoform 2 |

| PIP | PALI interaction with PRC2 |

| FAME | Fatty acid methyl ester |

References

- Bauman, D.E.; Currie, W.B. Partitioning of nutrients during pregnancy and lactation—A review of mechanisms involving homeostasis and homeorhesis. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63, 1514–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, E.; Teuscher, F.; Ender, K.; Wegner, J. Growth- and breed-related changes of marbling characteristics in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, C.; Bellmann, O.; Voigt, J.; Wegner, J.; Guiard, V.; Ender, K. An experimental approach for studying the genetic and physiological background of nutrient transformation in cattle with respect to nutrient secretion and accretion type. Arch. Tierz. 2002, 45, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, A.; Takasuga, A.; Setoguchi, K.; Pfuhl, R.; Flisikowski, K.; Fries, R.; Klopp, N.; Fürbass, R.; Weikard, R.; Kühn, C. Dissection of genetic factors modulating fetal growth in cattle indicates a substantial role of the non-SMC condensin I complex, subunit G (NCAPG) gene. Genetics 2009, 183, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikard, R.; Altmaier, E.; Suhre, K.; Weinberger, K.M.; Hammon, H.M.; Albrecht, E.; Setoguchi, K.; Takasuga, A.; Kühn, C. Metabolomic profiles indicate distinct physiological pathways affected by two loci with major divergent effect on Bos taurus growth and lipid deposition. Physiol. Genom. 2010, 42A, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setoguchi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Weikard, R.; Albrecht, E.; Kühn, C.; Kinoshita, A.; Sugimoto, Y.; Takasuga, A. The SNP c.1326T>G in the non-SMC condensin I complex, subunit G (NCAPG) gene encoding a p.Ile442Met variant is associated with an increase in body frame size at puberty in cattle. Anim. Genet. 2011, 42, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmann, P.; Reverter, A.; Fortes, M.R.; Weikard, R.; Suhre, K.; Hammon, H.M.; Albrecht, E.; Kuehn, C. A systems biology approach using metabolomic data reveals genes and pathways interacting to modulate divergent growth in cattle. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmann, P.; Reverter, A.; Weikard, R.; Suhre, K.; Hammon, H.M.; Albrecht, E.; Kuehn, C. Systems biology analysis merging phenotype, metabolomic and genomic data identifies Non-SMC Condensin I Complex, Subunit G (NCAPG) and cellular maintenance processes as major contributors to genetic variability in bovine feed efficiency. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobet, L.; Poncelet, D.; Royo, L.J.; Brouwers, B.; Pirottin, D.; Michaux, C.; Ménissier, F.; Zanotti, M.; Dunner, S.; Georges, M. Molecular definition of an allelic series of mutations disrupting the myostatin function and causing double-muscling in cattle. Mamm. Genome 1998, 9, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M.; Smith, T.P.; Bass, J.J. Mutations in myostatin (GDF8) in double-muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese cattle. Genome Res. 1997, 7, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, P.F. Double muscling in cattle: A review. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1995, 46, 1493–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purfield, D.C.; Evans, R.D.; Berry, D.P. Reaffirmation of known major genes and the identification of novel candidate genes associated with carcass-related metrics based on whole genome sequence within a large multi-breed cattle population. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allais, S.; Levéziel, H.; Payet-Duprat, N.; Hocquette, J.F.; Lepetit, J.; Rousset, S.; Denoyelle, C.; Bernard-Capel, C.; Journaux, L.; Bonnot, A.; et al. The two mutations, Q204X and nt821, of the myostatin gene affect carcass and meat quality in young heterozygous bulls of French beef breeds. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csürhés, T.; Szabó, F.; Holló, G.; Mikó, E.; Török, M.; Bene, S. Relationship between some Myostatin variants and meat production related calving, weaning and muscularity traits in charolais cattle. Animals 2023, 13, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholm-Perry, A.K.; Kuehn, L.A.; Oliver, W.T.; Sexten, A.K.; Miles, J.R.; Rempel, L.A.; Cushman, R.A.; Freetly, H.C. Adipose and muscle tissue gene expression of two genes (NCAPG and LCORL) located in a chromosomal region associated with cattle feed intake and gain. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makvandi-Nejad, S.; Hoffman, G.E.; Allen, J.J.; Chu, E.; Gu, E.; Chandler, A.M.; Loredo, A.I.; Bellone, R.R.; Mezey, J.G.; Brooks, S.A.; et al. Four loci explain 83% of size variation in the horse. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetens, J.; Widmann, P.; Kühn, C.; Thaller, G. A genome-wide association study indicates LCORL/NCAPG as a candidate locus for withers height in German Warmblood horses. Anim. Genet. 2013, 44, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamun, H.A.; Kwan, P.; Clark, S.A.; Ferdosi, M.H.; Tellam, R.; Gondro, C. Genome-wide association study of body weight in Australian Merino sheep reveals an orthologous region on OAR6 to human and bovine genomic regions affecting height and weight. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2015, 47, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.; Möller, S.; Stock, K.F.; Nolte, W.; von Depka Prondzinski, M.; Reents, R.; Kalm, E.; Kühn, C.; Thaller, G.; Falker-Gieske, C.; et al. Genomic analyses of withers height and linear conformation traits in German Warmblood horses using imputed sequence-level genotypes. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2024, 56, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.P.; Tribout, T.; Kadri, N.K.; Chitneedi, P.K.; Maak, S.; Hozé, C.; Boussaha, M.; Croiseau, P.; Philippe, R.; Spengeler, M.; et al. Sequence-based GWAS meta-analyses for beef production traits. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 70, Erratum in Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-023-00852-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeres, L.E.; Dilger, A.C.; Shike, D.W.; McCann, J.C.; Beever, J.E. Defining a haplotype encompassing the LCORL-NCAPG locus associated with increased lean growth in beef cattle. Genes 2024, 15, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, E.; Bennett, G.L.; Smith, T.P.; Cundiff, L.V. Association of myostatin on early calf mortality, growth, and carcass composition traits in crossbred cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 82, 2913–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.A.; Purfield, D.C.; Naderi, S.; Berry, D.P. Associations between polymorphisms in the myostatin gene with calving difficulty and carcass merit in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Gao, X.; Zhu, B.; Gao, H.; Ni, H.; Chen, Y. Multi-strategy genome-wide association studies identify the DCAF16-NCAPG region as a susceptibility locus for average daily gain in cattle. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Xu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, L.; Gao, H.; Song, J.; Li, J.; et al. Integration of selection signatures and multi-trait GWAS reveals polygenic genetic architecture of carcass traits in beef cattle. Genomics 2021, 113, 3325–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deveaux, V.; Cassar-Malek, I.; Picard, B. Comparison of contractile characteristics of muscle from Holstein and double-muscled Belgian Blue foetuses. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001, 131, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennebry, A.; Berry, C.; Siriett, V.; O’Callaghan, P.; Chau, L.; Watson, T.; Sharma, M.; Kambadur, R. Myostatin regulates fiber-type composition of skeletal muscle by regulating MEF2 and MyoD gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C525–C534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, S.; Miyake, M.; Watanabe, K.; Aso, H.; Hayashi, S.; Ohwada, S.; Yamaguchi, T. Myostatin preferentially down-regulates the expression of fast 2x myosin heavy chain in cattle. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2008, 84, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Huynh, T.V.; Lee, Y.S.; Sebald, S.M.; Wilcox-Adelman, S.A.; Iwamori, N.; Lepper, C.; Matzuk, M.M.; Fan, C.M. Role of satellite cells versus myofibers in muscle hypertrophy induced by inhibition of the myostatin/activin signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2353–E2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amthor, H.; Otto, A.; Vulin, A.; Rochat, A.; Dumonceaux, J.; Garcia, L.; Mouisel, E.; Hourdé, C.; Macharia, R.; Friedrichs, M.; et al. Muscle hypertrophy driven by myostatin blockade does not require stem/precursor-cell activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7479–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Albrecht, E.; Ender, K.; Wegner, J. Computer image analysis of intramuscular adipocytes and marbling in the longissimus muscle of cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 3251–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalbe, C.; Priepke, A.; Nürnberg, G.; Dannenberger, D. Effects of Long-Term Microalgae Supplementation on Muscle Microstructure, Meat Quality and Fatty Acid Composition in Growing Pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xiao, W.; Qin, X.; Cai, G.; Chen, H.; Hua, Z.; Cheng, C.; Li, X.; Hua, W.; Xiao, H.; et al. Myostatin regulates fatty acid desaturation and fat deposition through MEF2C/miR222/SCD5 cascade in pigs. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J. Targeting the myostatin signaling pathway to treat muscle loss and metabolic dysfunction. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e148372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J. Myostatin: A Skeletal Muscle Chalone. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.H.; Ahmad, K.; Moon, J.S.; Park, S.Y.; Ho Lim, J.; Chun, H.J.; Qadri, A.F.; Hwang, Y.C.; Jan, A.T.; Ahmad, S.S.; et al. Myostatin and its Regulation: A Comprehensive Review of Myostatin Inhibiting Strategies. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 876078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xing, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, Q.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. NCAPG dynamically coordinates the myogenesis of fetal bovine tissue by adjusting chromatin accessibility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Guo, D.; Jia, X.; Shi, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Unlocking the transcriptional control of NCAPG in bovine myoblasts: CREB1 and MYOD1 as key players. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setoguchi, K.; Furuta, M.; Hirano, T.; Nagao, T.; Watanabe, T.; Sugimoto, Y.; Takasuga, A. Cross-breed comparisons identified a critical 591-kb region for bovine carcass weight QTL (CW-2) on chromosome 6 and the Ile-442-Met substitution in NCAPG as a positional candidate. BMC Genet. 2009, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Mukiibi, R.; Chen, L.; Vinsky, M.; Plastow, G.; Basarab, J.; Stothard, P.; Li, C. Genetic architecture of quantitative traits in beef cattle revealed by genome wide association studies of imputed whole genome sequence variants: II: Carcass merit traits. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Cai, Y.; Qi, M.; Liang, C.; Pan, L.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Cao, X.; Yang, Q.; Ren, G.; et al. LCORL and STC2 variants increase body size and growth rate in cattle and other animals. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2025, 23, qzaf025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfuhl, R.; Bellmann, O.; Kühn, C.; Teuscher, F.; Ender, K.; Wegner, J. Beef versus dairy cattle: A comparison of feed conversion, carcass composition, and meat quality. Arch. Tierz. 2007, 50, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. AOAC Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; The Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, E.; Gotoh, T.; Ebara, F.; Xu, J.X.; Viergutz, T.; Nürnberg, G.; Maak, S.; Wegner, J. Cellular conditions for intramuscular fat deposition in Japanese Black and Holstein steers. Meat Sci. 2011, 89, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Albrecht, E.; Chitneedi, P.K.; Dannenberger, D.; Kühn, C.; Maak, S. Impact of Mutations in the NCAPG and MSTN Genes on Body Composition, Structural Properties of Skeletal Muscle, Its Fatty Acid Composition, and Meat Quality of Bulls from a Charolais × Holstein F2 Cross. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020882

Albrecht E, Chitneedi PK, Dannenberger D, Kühn C, Maak S. Impact of Mutations in the NCAPG and MSTN Genes on Body Composition, Structural Properties of Skeletal Muscle, Its Fatty Acid Composition, and Meat Quality of Bulls from a Charolais × Holstein F2 Cross. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020882

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbrecht, Elke, Praveen Krishna Chitneedi, Dirk Dannenberger, Christa Kühn, and Steffen Maak. 2026. "Impact of Mutations in the NCAPG and MSTN Genes on Body Composition, Structural Properties of Skeletal Muscle, Its Fatty Acid Composition, and Meat Quality of Bulls from a Charolais × Holstein F2 Cross" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020882

APA StyleAlbrecht, E., Chitneedi, P. K., Dannenberger, D., Kühn, C., & Maak, S. (2026). Impact of Mutations in the NCAPG and MSTN Genes on Body Composition, Structural Properties of Skeletal Muscle, Its Fatty Acid Composition, and Meat Quality of Bulls from a Charolais × Holstein F2 Cross. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020882