Multicellular Model Reveals the Mechanism of AEE Alleviating Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury via Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

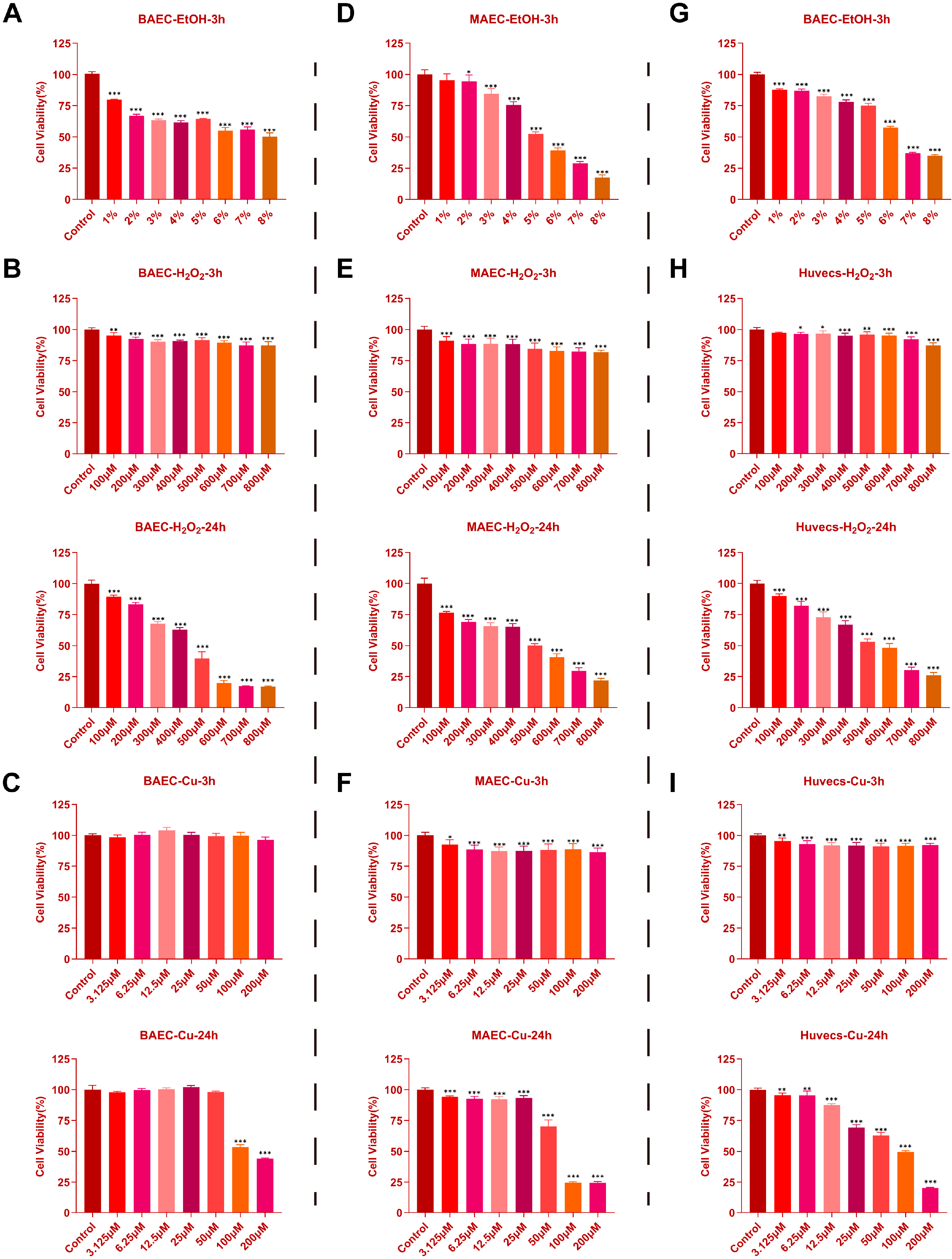

2.1. Effects of EtOH, H2O2, and CuSO4 on Cell Viability in BAECs, MAECs, and Huvecs

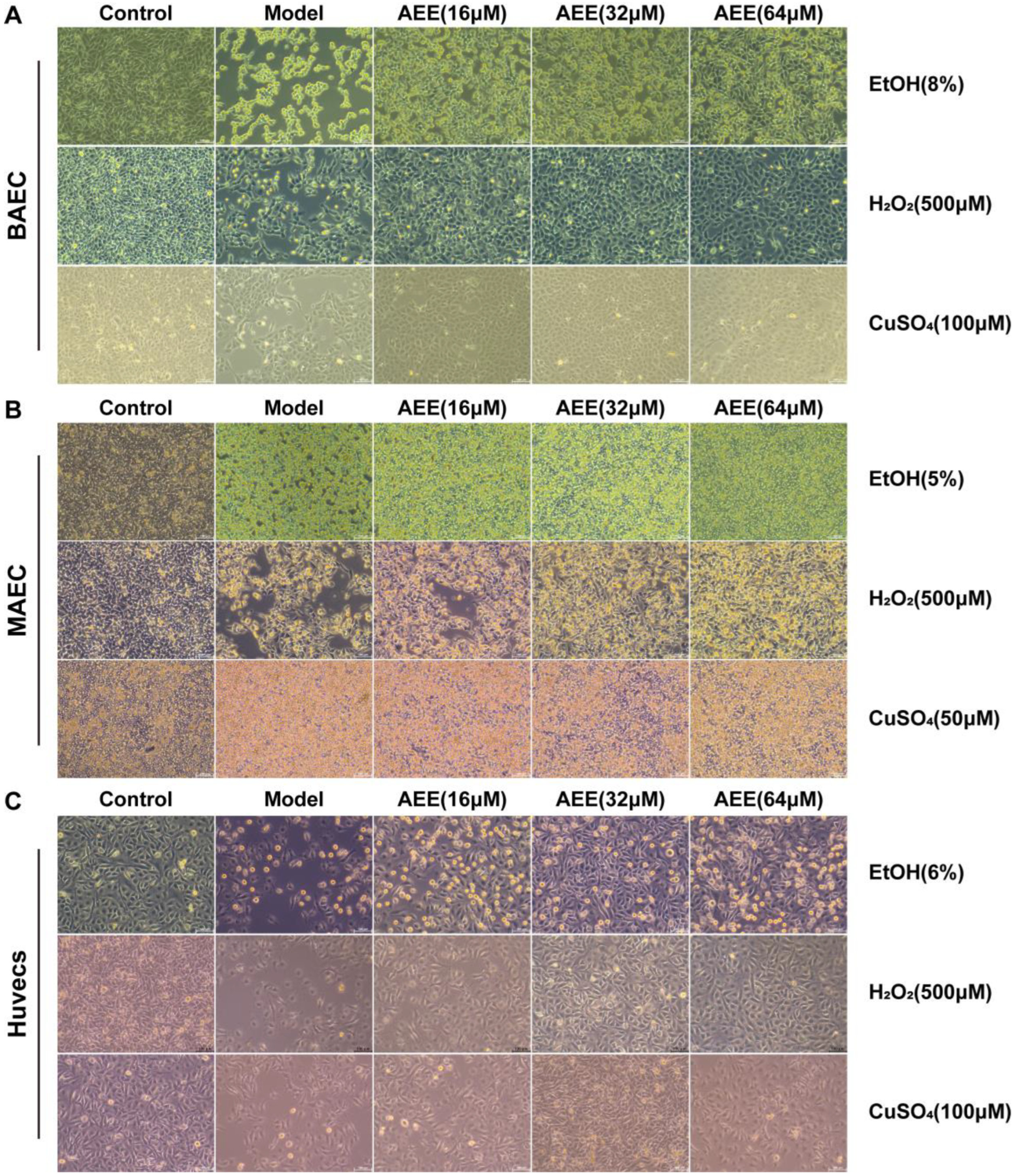

2.2. Protective Effects of AEE Against EtOH, H2O2, and CuSO4 Induced Injury in BAECs, MAECs, and Huvecs

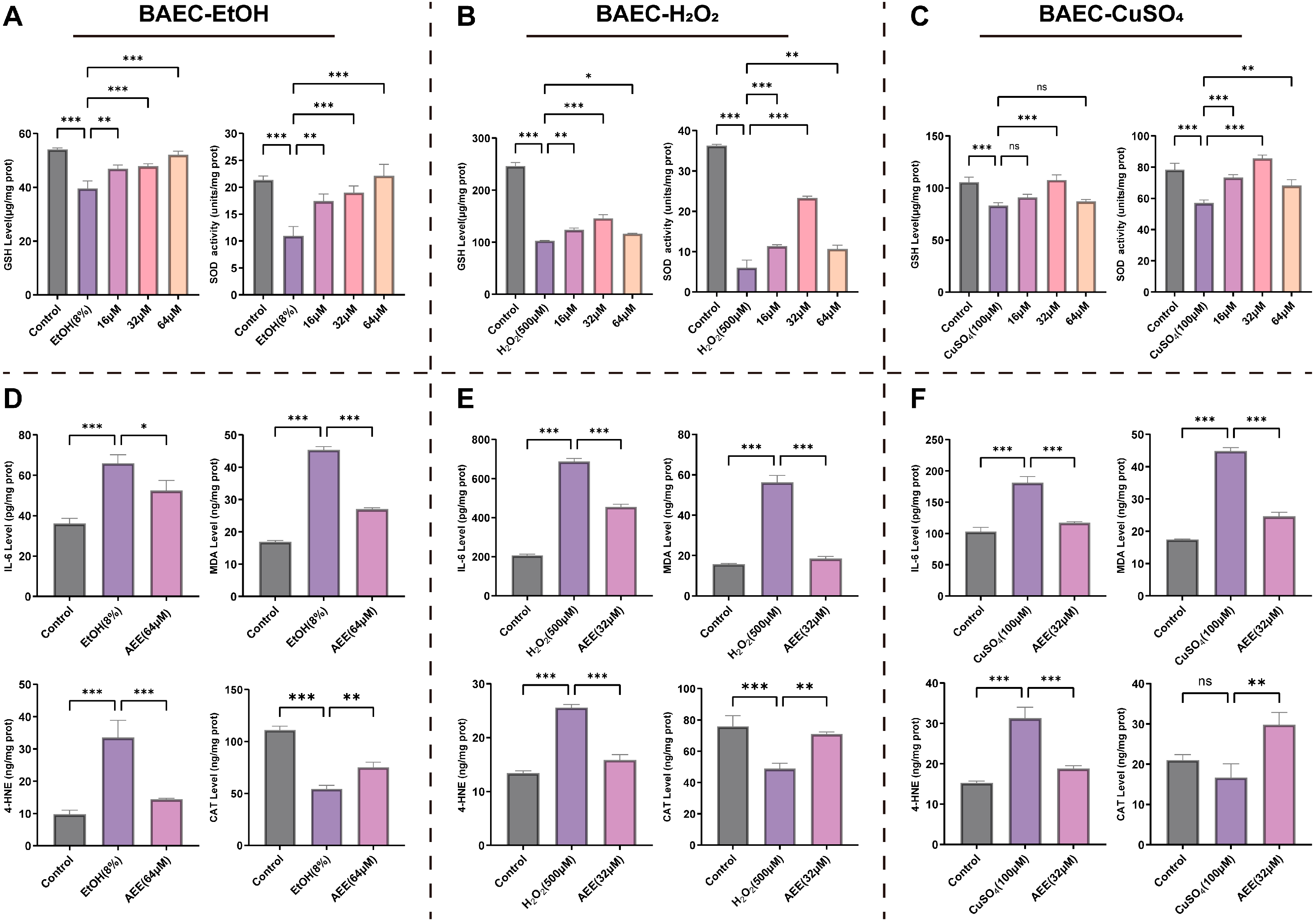

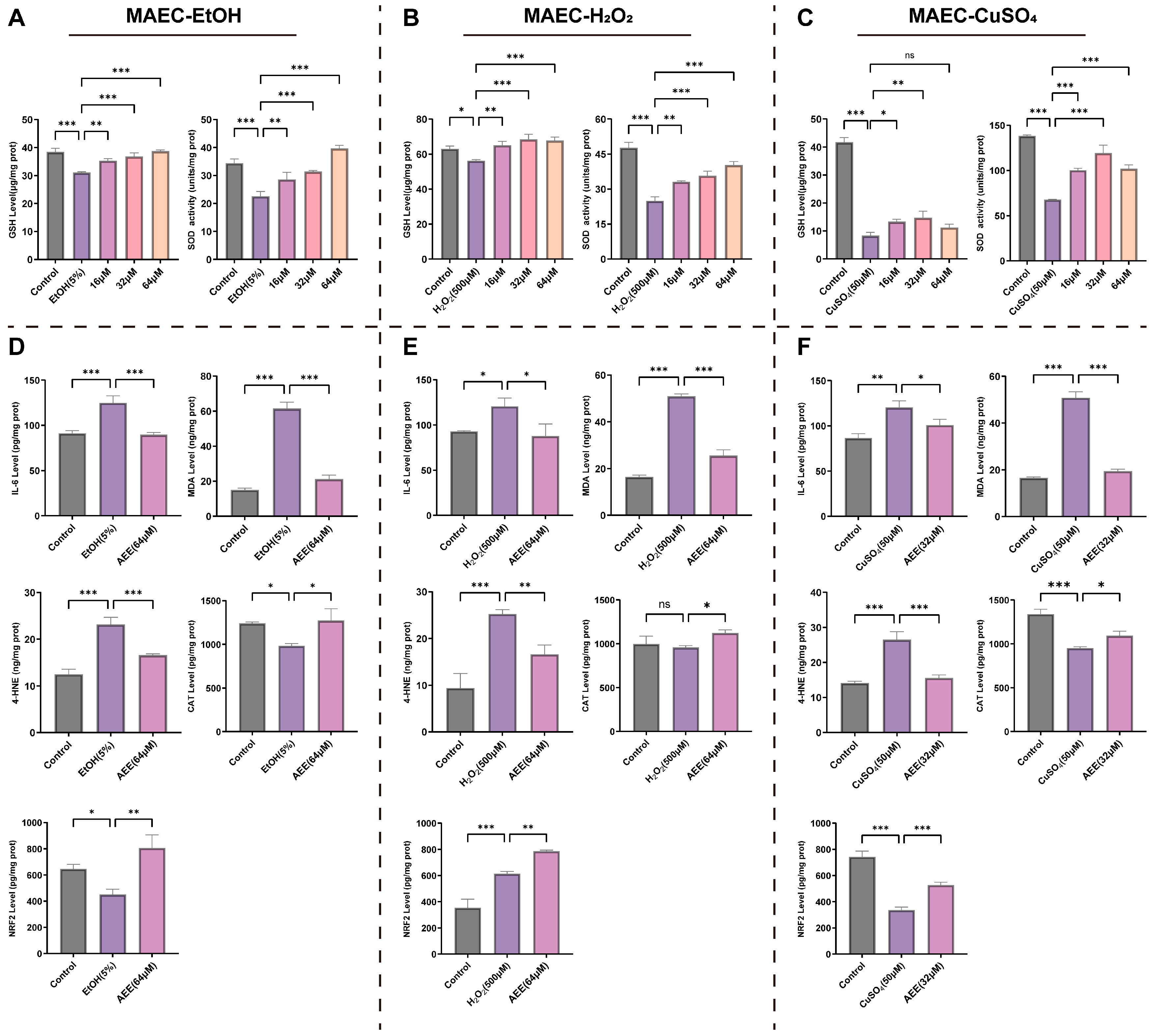

2.3. AEE Alleviates Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Various VECs

2.3.1. AEE Alleviates EtOH-, H2O2-, or CuSO4-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in BAECs

2.3.2. AEE Alleviates EtOH-, H2O2-, or CuSO4-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in MAECs

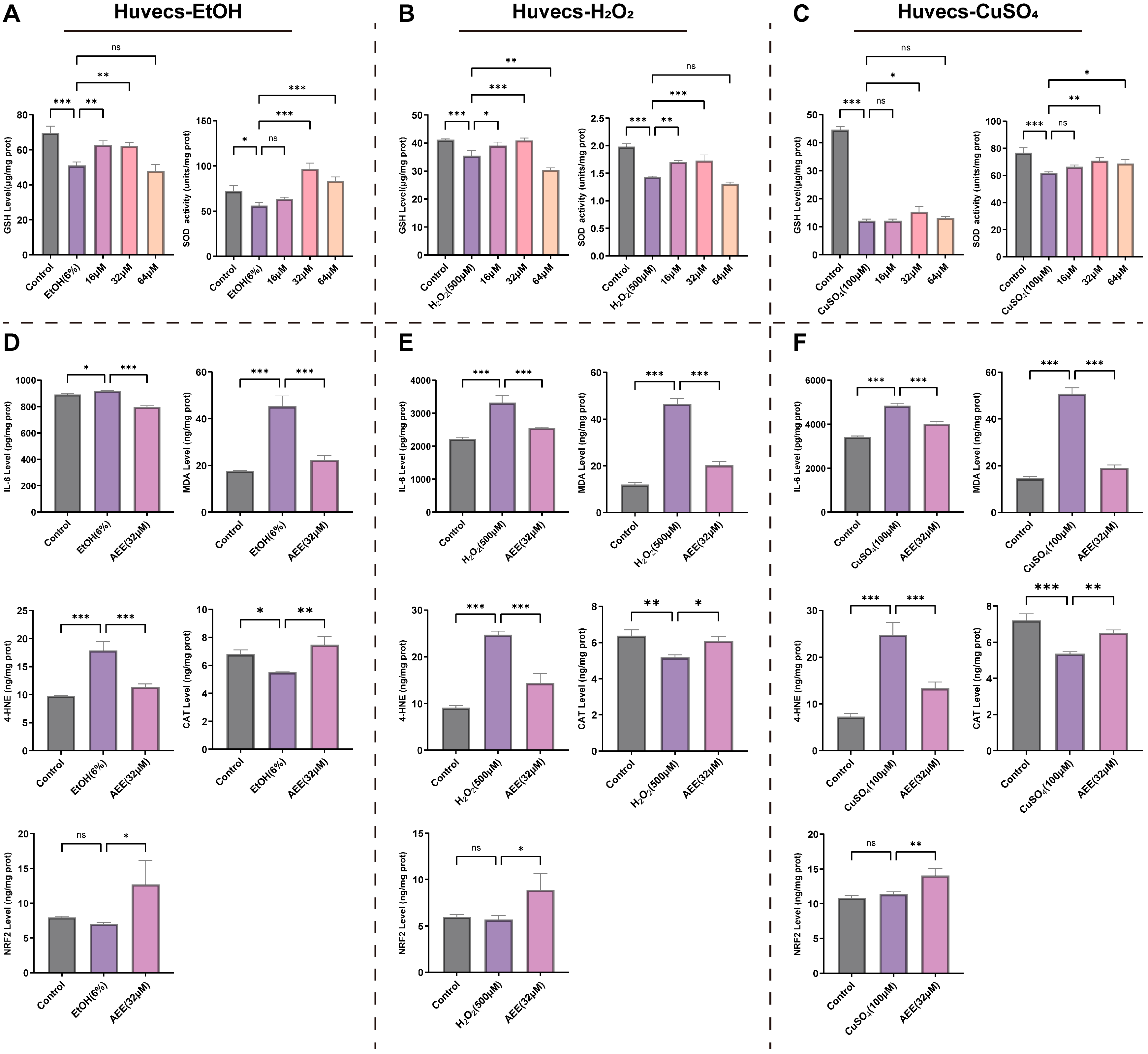

2.3.3. AEE Alleviates EtOH-, H2O2-, or CuSO4-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Huvecs

2.4. Metabolomic Analysis

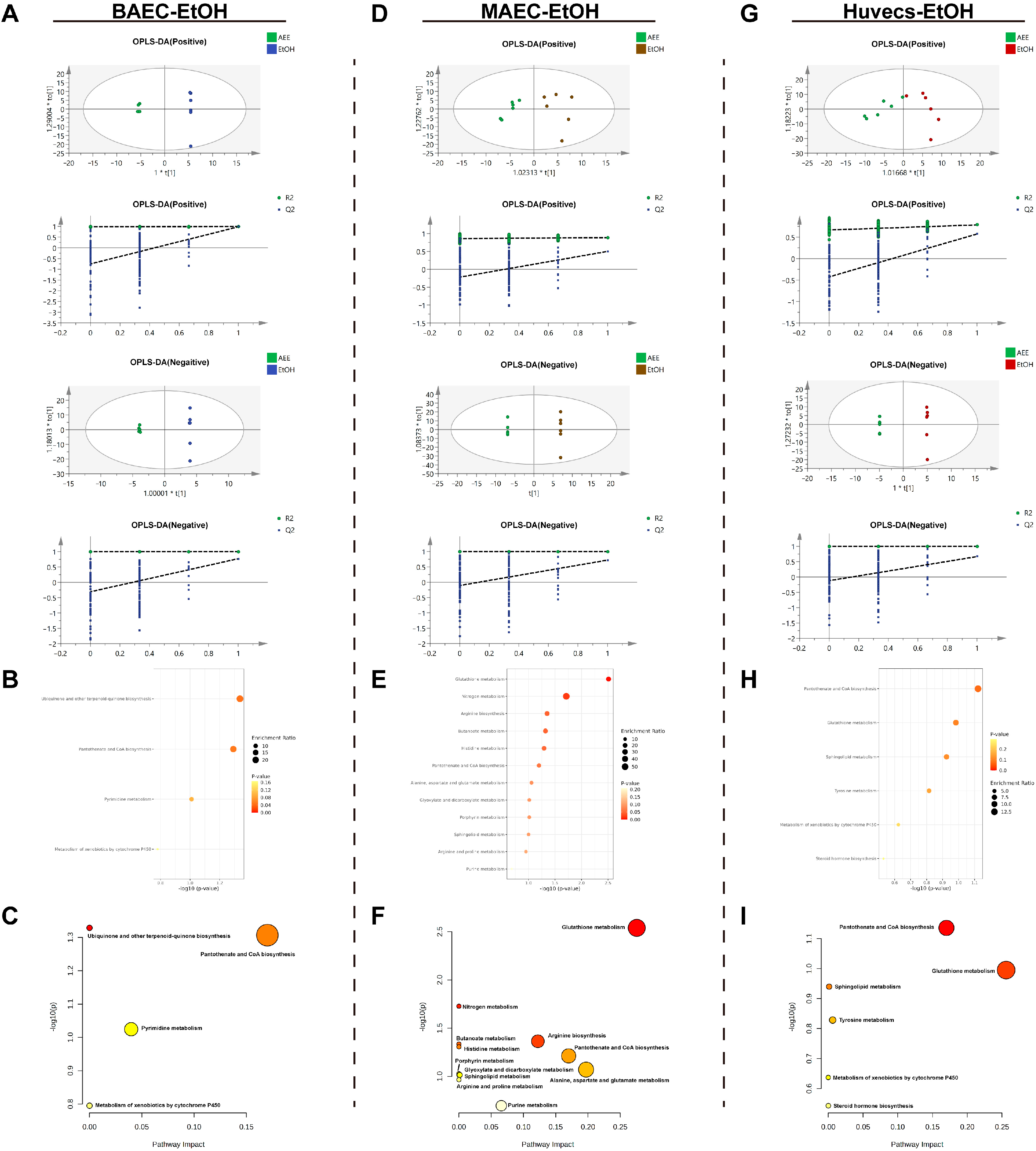

2.4.1. Metabolomic Analysis of the EtOH-Induced Cell Injury Model

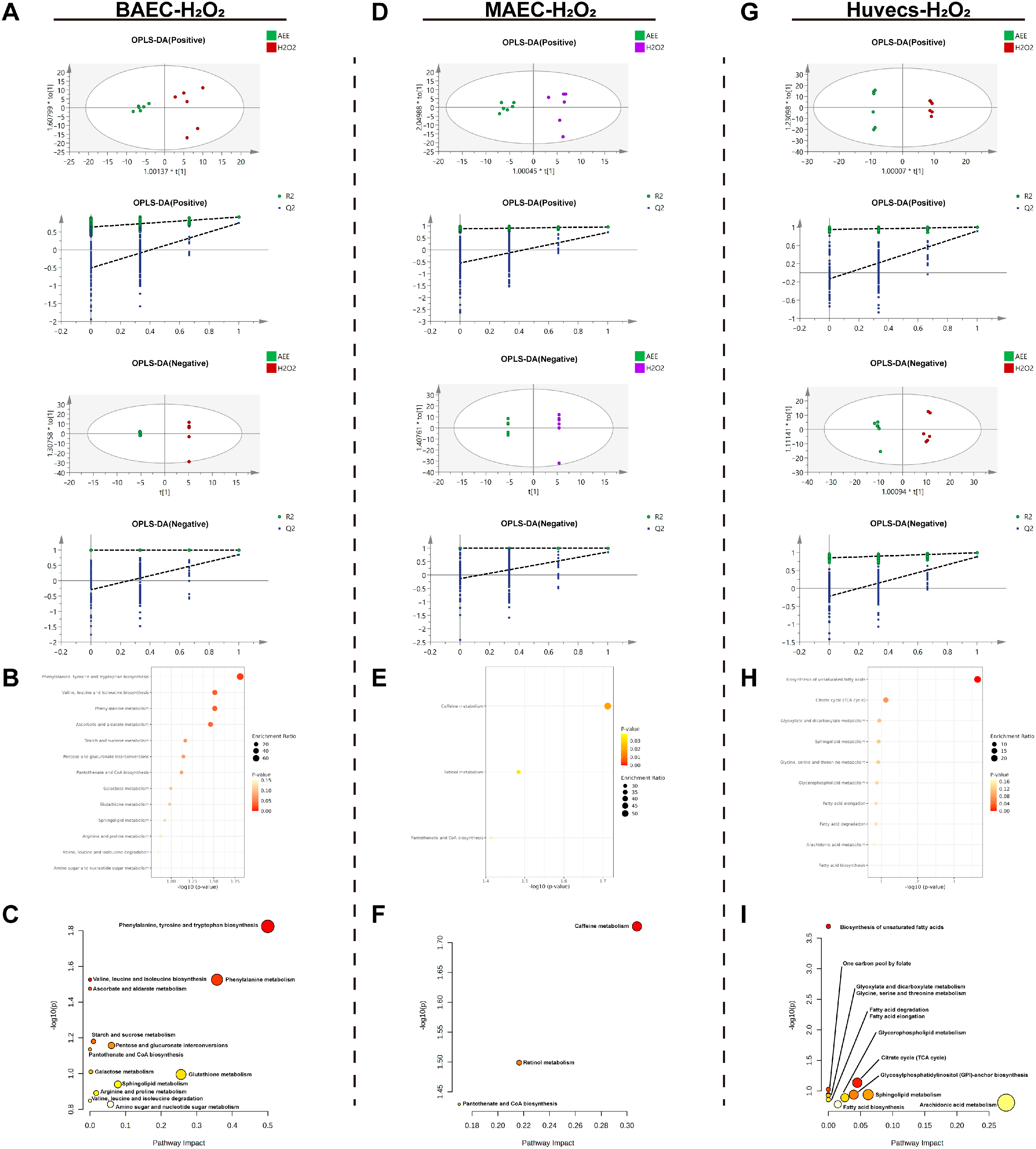

2.4.2. Metabolomic Analysis of the H2O2-Induced Cell Injury Model

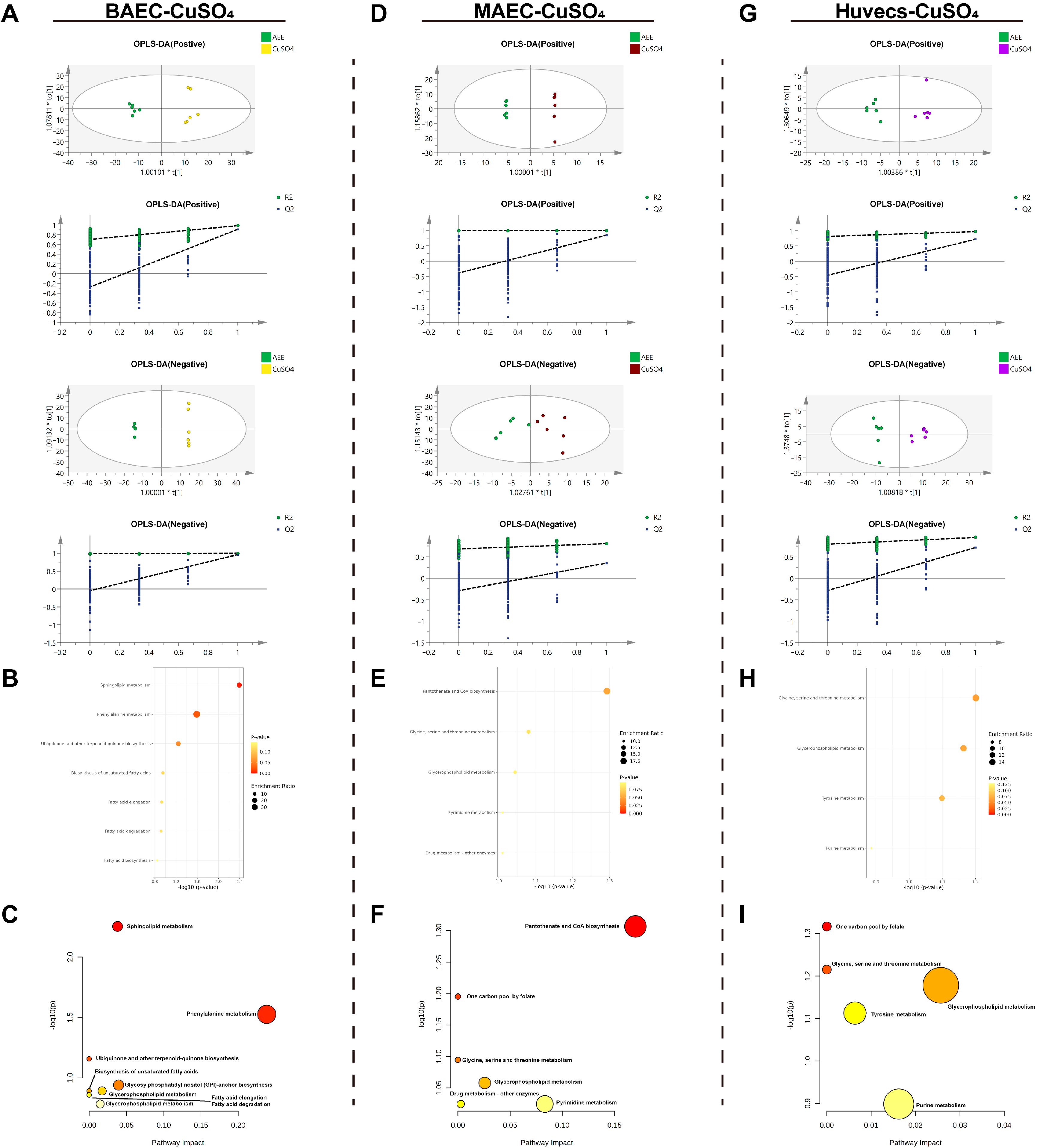

2.4.3. Metabolomic Analysis of the CuSO4-Induced Cell Injury Model

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Overview of Study Design

4.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

4.4. Cell Culture

4.5. Cell Viability Assay

4.6. Cell Experiment Design

4.7. GSH Level Measurement

4.8. SOD Activity Assay

4.9. Cell Metabonomic Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asatiani, N.; Sapojnikova, N.; Kartvelishvili, T.; Asanishvili, L.; Sichinava, N.; Chikovani, Z. Blood Catalase, Superoxide Dismutase, and Glutathione Peroxidase Activities in Alcohol- and Opioid-Addicted Patients. Medicina 2025, 61, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, L.L.; Rios, F.J.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Reactive oxygen species in hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanschel, A.C.B.A.; Guizoni, D.M.; Lorza-Gil, E.; Salerno, A.G.; Paiva, A.A.; Dorighello, G.G.; Davel, A.P.; Balkan, W.; Hare, J.M.; Oliveira, H.C.F. The Presence of Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein (CETP) in Endothelial Cells Generates Vascular Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, N.K.; Liu, W.M.; Cahill, P.A.; Redmond, E.M. Alcohol and vascular endothelial function: Biphasic effect highlights the importance of dose. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 47, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.C.; Khan, D.; Rana, M.; Haenggi, D.; Muhammad, S. Doxycycline Attenuated Ethanol-Induced Inflammaging in Endothelial Cells: Implications in Alcohol-Mediated Vascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zou, Z.; Wang, B.; Xu, G.; Chen, C.; Qin, X.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J. Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Oxidative DNA Damage and Cell Death via Copper Ion-Mediated P38 MAPK Activation in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 3291–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.Q.; Tang, Z.X.; Li, Y.; Hu, L.M.; Pan, J.Q. The Effects of Copper on Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells and Claudin Via Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 174, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.H.; Cen, X.J.; Zhao, R.C.; Wang, J.; Cui, H.B. PRMT5 knockdown enhances cell viability and suppresses cell apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in ox-LDL-induced vascular endothelial cells via interacting with PDCD4. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.J.; Xu, R.; Wang, X.P.; Zhao, X.Y.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Ma, S.; Di, X.H.; Wu, W.; et al. Nogo-B mediates endothelial oxidative stress and inflammation to promote coronary atherosclerosis in pressure-overloaded mouse hearts. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.C.; Ma, Y.H.; Wen, J.P.; He, X.K.; Zhang, X.H. Increased inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in endothelial and macrophage cells exacerbate atherosclerosis in ApoCIII transgenic mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchio, P.; Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Vila, J.M.; Aldasoro, M.; Victor, V.M.; Mauricio, M.D. Targeting Early Atherosclerosis: A Focus on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8563845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backston, K.; Morgan, J.; Patel, S.; Koka, R.; Hu, J.J.; Raina, R. Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction: The Pathogenesis of Pediatric Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Patil, S.M.; Dasgupta, A.; Podder, A.; Kumar, J.; Sindwani, P.; Karumuri, P. Unravelling the Intricate Relationship Between Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension. Cureus J. Med. Sci. 2024, 16, e61245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, V.; Lobysheva, I.; Gérard, L.; Vermeersch, M.; Perez-Morga, D.; Castelein, T.; Mesland, J.B.; Hantson, P.; Collienne, C.; Gruson, D.; et al. Oxidative stress-induced endothelial dysfunction and decreased vascular nitric oxide in COVID-19 patients. Ebiomedicine 2022, 77, 103893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.F.; Zhu, S.L.; Hou, J.X.; Tang, Y.F.; Liu, J.X.; Xu, Q.B.; Sun, H.Z. The hindgut microbiome contributes to host oxidative stress in postpartum dairy cows by affecting glutathione synthesis process. Microbiome 2023, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordillo, L.M.; Raphael, W. Significance of Metabolic Stress, Lipid Mobilization, and Inflammation on Transition Cow Disorders. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2013, 29, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordillo, L.M.; Aitken, S.L. Impact of oxidative stress on the health and immune function of dairy cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunop. 2009, 128, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Fang, Z.H.; Duan, H.W.; Dong, W.T.; Xiao, L.F. Ginsenoside Rg1 Alleviates Blood-Milk Barrier Disruption in Subclinical Bovine Mastitis by Regulating Oxidative Stress-Induced Excessive Autophagy. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkema, C.; Grandin, T. Graduate Student Literature Review: Udder edema in dairy cattle-A possible emerging animal welfare issue. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7334–7341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.Y.; Feng, X.; Luan, J.M.; Ji, S.; Jin, Y.H.; Zhang, M. Improved tenderness of beef from bulls supplemented with active dry yeast is related to matrix metalloproteinases and reduced oxidative stress. Animal 2022, 16, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.F.; Long, S.F.; Yi, G.; Wang, X.L.; Li, J.G.; Wu, Z.L.; Guo, Y.; Sun, F.; Liu, J.J.; Chen, Z.H. Heating Drinking Water in Cold Season Improves Growth Performance via Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity and Rumen Fermentation Function of Beef Cattle. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.F.; Yi, G.; Li, J.G.; Wu, Z.L.; Guo, Y.; Sun, F.; Liu, J.J.; Tang, C.J.; Long, S.F.; Chen, Z.H. Dietary Supplementation of Tannic Acid Promotes Performance of Beef Cattle via Alleviating Liver Lipid Peroxidation and Improving Glucose Metabolism and Rumen Fermentation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.Z.; Yang, Y.J.; Liu, X.W.; Qin, Z.; Li, J.Y. Aspirin Eugenol Ester Reduces H2O2 -Induced Oxidative Stress of HUVECs via Mitochondria-Lysosome Axis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8098135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.Z.; Zhang, Z.D.; Yang, Y.J.; Liu, X.W.; Qin, Z.; Li, J.Y. Aspirin Eugenol Ester Protects Vascular Endothelium From Oxidative Injury by the Apoptosis Signal Regulating Kinase-1 Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 588755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.D.; Yang, Y.J.; Liu, X.W.; Qin, Z.; Li, S.H.; Li, J.Y. Aspirin eugenol ester ameliorates paraquat-induced oxidative damage through ROS/p38-MAPK-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Toxicology 2021, 453, 152721, Correction in Toxicology 2021, 454, 152763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2021.152763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwardeen, N.R.; Diboun, I.; Mokrab, Y.; Althani, A.A.; Elrayess, M.A. Statistical methods and resources for biomarker discovery using metabolomics. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.R.; Patel, R.; Kirsch, D.G.; Lewis, C.A.; Vander Heiden, M.G.; Locasale, J.W. Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA-Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Zhang, Z.D.; Qin, Z.; Liu, X.W.; Li, S.H.; Bai, L.X.; Ge, W.B.; Li, J.Y.; Yang, Y.J. Aspirin eugenol ester alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats while stabilizing serum metabolites levels. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 939106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Fan, L.P.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, X.W.; Qin, Z.; Li, J.Y.; Yang, Y.J. Platelet Proteomics and Tissue Metabolomics Investigation for the Mechanism of Aspirin Eugenol Ester on Preventive Thrombosis Mechanism in a Rat Thrombosis Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.H. The effects of exogenous H2O2 on cell death, reactive oxygen species and glutathione levels in calf pulmonary artery and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Liang, J.H.; He, M.J.; Jiang, B.Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.S.; Li, P.; Du, B. Pueraria lobata-derived peptides hold promise as a novel antioxidant source by mitigating ethanol-induced oxidative stress in HepG2 cells through regulating the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Food Chem. 2025, 490, 145014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, Y. Roles of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction-Related Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegaard, A.O.; Jacobs, D.R.; Sanchez, O.A.; Goff, D.C.; Reiner, A.P.; Gross, M.D. Oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2016, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.P.; Liu, H.Q.; Zhao, X.Q.; Mamateli, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.T.; Cai, J.; Qiao, T. Oridonin attenuates low shear stress-induced endothelial cell dysfunction and oxidative stress by activating the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathway. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.P.; Yang, R.; Jiang, F.J.; Guo, J.B.; Lu, X.Y.; Yang, T.; He, Q.Y. Molecular Mechanism of Astragaloside IV in Improving Endothelial Dysfunction of Cardiovascular Diseases Mediated by Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1481236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.X.; Zhao, X.M.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Ou, Y.J.; Zhang, H.W.; Li, X.M.; Wu, X.H.; Wang, L.X.; Li, M.; et al. MLKL-mediated endothelial necroptosis drives vascular damage and mortality in systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Gao, Y.L.; Cui, L.; Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Lv, W.Q.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.K. α-Ketoglutarate Attenuates Hyperlipidemia-Induced Endothelial Damage by Activating the Erk-Nrf2 Signaling Pathway to Inhibit Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 39, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, D.C.; Di Pino, F.L.; Monte, I.P. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Vascular Damage: Unraveling Novel Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Fabry Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, A.; Rauch, A.; Staessens, S.; Moussa, M.; Rosa, M.; Corseaux, D.; Jeanpierre, E.; Goutay, J.; Caplan, M.; Varlet, P.; et al. Vascular Endothelial Damage in the Pathogenesis of Organ Injury in Severe COVID-19. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 1760–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Zhao, J.; Gao, M.Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.Y. Mechanism of nano-plastics induced inflammation injury in vascular endothelial cells. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 154, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Nam, M.H.; Park, K.Y. Phytosphingosine induces systemic acquired resistance through activation of sphingosine kinase. Plant Direct 2021, 5, e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.Y.; Yang, S.G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhao, Y.S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.X. Recent Progress in the Diverse Synthetic Approaches to Phytosphingosine. Top. Curr. Chem. 2025, 383, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavicic, T.; Wollenweber, U.; Farwick, M.; Korting, H.C. Anti-microbial and -inflammatory activity and efficacy of phytosphingosine: An in vitro and in vivo study addressing acne vulgaris. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2007, 29, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.T.; Kim, M.J.; Kang, Y.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, J.A.; Kang, C.M.; Cho, C.K.; Kang, S.; Bae, S.; et al. Phytosphingosine in combination with ionizing radiation enhances apoptotic cell death in radiation-resistant cancer cells through ROS-dependent and -independent AEF release. Blood 2005, 105, 1724–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Xu, J.W.; Zhao, C.J.; Bao, L.J.; Wu, K.Y.; Feng, L.J.; Sun, H.; Shang, S.; Hu, X.Y.; Sun, Q.S.; et al. Phytosphingosine alleviates aureus-induced mastitis by inhibiting inflammatory responses and improving the blood-milk barrier in mice. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murru, E.; Manca, C.; Carta, G.; Banni, S. Impact of Dietary Palmitic Acid on Lipid Metabolism. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 861664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, S.L.; Jiang, L.J.; Wu, K.J.; Chen, S.S.; Su, L.J.; Liu, C.; Liu, P.Q.; Luo, W.W.; Zhong, S.L.; et al. Palmitic Acid Accelerates Endothelial Cell Injury and Cardiovascular Dysfunction via Palmitoylation of PKM2. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Zhang, Y.M.; Deng, Q.H.; Mao, J.D.; Jia, Z.W.; Tang, M.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.K.; Chen, J.J.; Wang, Y.R.; et al. Resveratrol reverses Palmitic Acid-induced cow neutrophils apoptosis through shifting glucose metabolism into lipid metabolism via Cav-1/CPT 1-mediated FAO enhancement. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 233, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, C.; Vors, C.; Penhoat, A.; Cheillan, D.; Michalski, M.C. Role of circulating sphingolipids in lipid metabolism: Why dietary lipids matter. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1108098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annevelink, C.E.; Sapp, P.A.; Petersen, K.S.; Shearer, G.C.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Diet-derived and diet-related endogenously produced palmitic acid: Effects on metabolic regulation and cardiovascular disease risk. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherratt, S.C.R.; Mason, R.P.; Libby, P.; Steg, P.G.; Bhatt, D.L. Do patients benefit from omega-3 fatty acids? Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 119, 2884–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.P.; Libby, P.; Bhatt, D.L. Emerging Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Protection for the Omega-3 Fatty Acid Eicosapentaenoic Acid. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.E. Dietary Sources of Omega-3 Fatty Acids Versus Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation Effects on Cognition and Inflammation. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenoshita, Y.; Tokito, A.; Jougasaki, M. Inhibitory Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid on Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-Induced Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, Interleukin-6, and Interleukin-8 in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, M.J.; Jung, H.S.; Kang, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Park, J.H. The Protective Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid for Stress-induced Accelerated Senescence in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, K.; Shi, P.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X.J.; Xu, J.L.; Liao, K. HSF1 Mediates Palmitic Acid-Disrupted Lipid Metabolism and Inflammatory Response by Maintaining Endoplasmic Reticulum Homeostasis in Fish. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 5236–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Fu, X.; Chen, Q.; Patra, J.K.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Gai, Z. Arachidonic Acid Metabolism and Kidney Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Khan, H.; Xiao, J.; Cheang, W.S. Effects of Arachidonic Acid Metabolites on Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arreola, J. WNK kinase, ion channels and arachidonic acid metabolites choreographically execute endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Cell Calcium 2024, 121, 102904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Botta, E.; Holinstat, M. Eicosanoids in inflammation in the blood and the vessel. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 997403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, M.G.; Ossani, G.; Monserrat, A.J.; Boveris, A. Oxidative damage: The biochemical mechanism of cellular injury and necrosis in choline deficiency. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2010, 88, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.X.; Pye, Q.N.; Williamson, K.S.; Stewart, C.A.; Hensley, K.L.; Kotake, Y.; Floyd, R.A.; Broyles, R.H. Reactive oxygen species in choline deficiency-induced apoptosis in rat hepatocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veskovic, M.; Mladenovic, D.; Jorgacevic, B.; Stevanovic, I.; de Luka, S.; Radosavljevic, T. Alpha-lipoic acid affects the oxidative stress in various brain structures in mice with methionine and choline deficiency. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015, 240, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossani, G.P.; Repetto, M.G.; Boveris, A.; Monserrat, A.J. The protective effect of menhaden oil in the oxidative damage and renal necrosis due to dietary choline deficiency. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I.H.R.; Abbasi, F.; Soomro, R.N.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Abdel-Latif, M.A.; Li, W.; Hao, R.; Sun, F.; Bodinga, B.M.; Hayat, K.; et al. Considering choline as methionine precursor, lipoproteins transporter, hepatic promoter and antioxidant agent in dairy cows. AMB Express 2017, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Darwish, W.S.; Terada, K.; Chiba, H.; Hui, S.P. Choline and Ethanolamine Plasmalogens Prevent Lead-Induced Cytotoxicity and Lipid Oxidation in HepG2 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7716–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Xu, L.; Porter, N.A. Free radical lipid peroxidation: Mechanisms and analysis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5944–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milkovic, L.; Zarkovic, N.; Marusic, Z.; Zarkovic, K.; Jaganjac, M. The 4-Hydroxynonenal-Protein Adducts and Their Biological Relevance: Are Some Proteins Preferred Targets? Antioxidants 2023, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankin, V.Z.; Tikhaze, A.K.; Melkumyants, A.M. Malondialdehyde as an Important Key Factor of Molecular Mechanisms of Vascular Wall Damage under Heart Diseases Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Fujioka, S.; Takahashi, R.; Oe, T. Angiotensin II-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Endothelial Cells: Modification of Cellular Molecules through Lipid Peroxidation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladykovskaya, E.; Sithu, S.D.; Haberzettl, P.; Wickramasinghe, N.S.; Merchant, M.L.; Hill, B.G.; McCracken, J.; Agarwal, A.; Dougherty, S.; Gordon, S.A.; et al. Lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal causes endothelial activation by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11398–11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carrio, J.; Cerro-Pardo, I.; Lindholt, J.S.; Bonzon-Kulichenko, E.; Martinez-Lopez, D.; Roldan-Montero, R.; Escola-Gil, J.C.; Michel, J.B.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Vazquez, J.; et al. Malondialdehyde-modified HDL particles elicit a specific IgG response in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 174, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.R.; Bhattacharyya, C.; Sarkar, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Sircar, E.; Dutta, S.; Sengupta, R. Glutathione: Role in Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress, Antioxidant Defense, and Treatments. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 4566–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.H.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D.; Milzani, A.; Dalle-Donne, I.; Rossi, R. How to Increase Cellular Glutathione. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.X.; Lu, J.Q.; Yu, D.Q.; Wei, X.B. Neohesperidin Dihydrochalcone Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Vascular Endothelium Dysfunction by Regulating Antioxidant Capacity. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e70107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Xu, G.; Yang, X.; Zou, Z.; Yu, C. Ferritinophagy is involved in the zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced ferroptosis of vascular endothelial cells. Autophagy 2021, 17, 4266–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.Z.; Hao, S.J.; Liu, K.Y.; Gao, M.Q.; Lu, B.; Sheng, F.Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.L.; Wu, D.; Han, Y.; et al. Airborne fine particulate matter (PM) damages the inner blood-retinal barrier by inducing inflammation and ferroptosis in retinal vascular endothelial cells. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Deruy, E.; Peugnet, V.; Turkieh, A.; Pinet, F. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, A.; Elwell, J.H.; Peterson, T.E.; Harrison, D.G. Release of intact endothelium-derived relaxing factor depends on endothelial superoxide dismutase activity. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 260, C219–C225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, S.; Ye, C.; Li, P.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, J. In vivo metabolic effects of naringin in reducing oxidative stress and protecting the vascular endothelium in dyslipidemic mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 139, 109866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.G.S.; Morelli, A.P.; Pavan, I.C.B.; Tavares, M.R.; Pestana, N.F.; Rostagno, M.A.; Simabuco, F.M.; Bezerra, R.M.N. Protective effects of beet (Beta vulgaris) leaves extract against oxidative stress in endothelial cells in vitro. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marracino, L.; Punzo, A.; Severi, P.; Nganwouo Tchoutang, R.; Vargas-De-la-Cruz, C.; Fortini, F.; Vieceli Dalla Sega, F.; Silla, A.; Porru, E.; Simoni, P.; et al. Fermentation of Vaccinium floribundum Berries with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Reduces Oxidative Stress in Endothelial Cells and Modulates Macrophages Function. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Duan, H.; Li, R.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling: An important molecular mechanism of herbal medicine in the treatment of atherosclerosis via the protection of vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harithpriya, K.; Ganesan, K.; Ramkumar, K.M. Pterostilbene Reverses Epigenetic Silencing of Nrf2 and Enhances Antioxidant Response in Endothelial Cells in Hyperglycemic Microenvironment. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, T.; Ouyang, H.; Huang, Z.; Lu, B.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Ji, L. Erianin alleviated liver steatosis by enhancing Nrf2-mediated VE-cadherin expression in vascular endothelium. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 950, 175744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Shen, J.; Niu, G.; Khusbu, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Bi, Y. Lycopene Protects Corneal Endothelial Cells from Oxidative Stress by Regulating the P62-Autophagy-Keap1/Nrf2 Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 10230–10245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Zhu, R.; He, L.; Chook, C.Y.B.; Li, H.; Leung, F.P.; Tse, G.; Chen, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.; Wong, W.T. Asperuloside as a Novel NRF2 Activator to Ameliorate Endothelial Dysfunction in High Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2025, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.Q.; Li, S.L.; Guo, W.N.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zhang, W.G.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y.M.; Yi, X.L.; Cui, T.T.; An, Y.W.; et al. Simvastatin Protects Human Melanocytes from H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress by Activating Nrf2. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.J.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Rehman, H.M.; Ahmed, N.; Nawaz, S.; Saleem, F.; Ahmad, S.; Uzair, M.; Rana, I.A.; Atif, R.M.; Zaman, Q.U.; et al. Using Exogenous Melatonin, Glutathione, Proline, and Glycine Betaine Treatments to Combat Abiotic Stresses in Crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.D.; Kuang, S.Y.; Wu, P.; Jiang, J.; Tang, L.; Tang, W.N.; Zhang, Y.A.; et al. Protective role of phenylalanine on the ROS-induced oxidative damage, apoptosis and tight junction damage via Nrf2, TOR and NF-κB signalling molecules in the gill of fish. Fish Shellfish. Immun. 2017, 60, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Dickman, M.B.; Becker, D.F. Proline modulates the intracellular redox environment and protects mammalian cells against oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhu, Y. Functions of Coenzyme A and Acyl-CoA in Post-Translational Modification and Human Disease. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatskyi, V.V.; Dobrzyn, P. Role of Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase 1 in Cardiovascular Physiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Yang, W.Q.; Luo, W.W.; Zhang, L.L.; Mai, Y.Q.; Li, Z.Q.; Liu, S.T.; Jiang, L.J.; Liu, P.Q.; Li, Z.M. Disturbance of Fatty Acid Metabolism Promoted Vascular Endothelial Cell Senescence via Acetyl-CoA-Induced Protein Acetylation Modification. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1198607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barritt, S.A.; DuBois-Coyne, S.E.; Dibble, C.C. Coenzyme A biosynthesis: Mechanisms of regulation, function and disease. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonenko, V.; Gout, I. Discovery and functional characterisation of protein CoAlation and the antioxidant function of coenzyme A. BBA Adv. 2023, 3, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inducer | Cell | Metabolites | Formula | SM | RT | m/z | VIP | FC (AEE/M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH | BAEC | Uridine | C9H12N2O6 | EST+ | 1.68 | 245.0780 | 1.3543 | 10.0367 ** |

| 2-(S-Glutathionyl) acetyl glutathione | C22H34N6O13S2 | EST− | 17.084 | 653.1437 | 1.8796 | 7.1396 * | ||

| 4′-Phosphopantothenoylcysteine | C12H23N2O9PS | EST− | 15.316 | 401.0808 | 1.8739 | 2.1642 ** | ||

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | EST− | 18.097 | 137.0226 | 2.4293 | 0.0008 *** | ||

| MAEC | Glutamic acid | C5H9NO4 | EST+ | 2.478 | 148.0577 | 1.2428 | 1.3132 ** | |

| Glutathione | C10H17N3O6S | EST+ | 2.528 | 308.0857 | 1.5946 | 27.7886 * | ||

| Adenosine monophosphate | C10H14N5O7P | EST+ | 2.715 | 348.0651 | 1.1843 | 0.4544 * | ||

| Phytosphingosine | C18H39NO3 | EST+ | 17.271 | 318.2955 | 1.5514 | 27.4347 * | ||

| 4′-Phosphopantothenoylcysteine | C12H23N2O9PS | EST− | 17.503 | 401.0853 | 1.8519 | 15.0864 *** | ||

| Huvecs | Homovanillin | C9H10O3 | EST+ | 2.75 | 167.0718 | 1.1007 | 21.6488 * | |

| Tetrahydrocorticosterone | C21H34O4 | EST+ | 3.857 | 351.2467 | 1.1185 | 78.0069 * | ||

| 1,2-Dihydronaphthalene-1,2-diol | C10H10O2 | EST+ | 17.979 | 163.0768 | 1.5327 | 1.2113 ** | ||

| Phytosphingosine | C18H39NO3 | EST+ | 18.176 | 318.2978 | 1.242 | 3.8590 * | ||

| 4′-Phosphopantothenoylcysteine | C12H23N2O9PS | EST− | 18.517 | 401.0848 | 1.0302 | 9.8905 * | ||

| Glutathione | C10H17N3O6S | EST− | 6.167 | 306.0768 | 1.715 | 3.0495 ** |

| Inducer | Cell | Metabolites | Formula | SM | RT | m/z | VIP | FC (AEE/M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O2 | BAEC | Proline | C5H9NO2 | EST+ | 2.322 | 116.0694 | 1.0932 | 19.3354 * |

| L-Valine | C5H11NO2 | EST+ | 2.458 | 118.0844 | 1.1375 | 13.3350 * | ||

| Glutathione | C10H17N3O6S | EST+ | 3.595 | 308.0879 | 1.0257 | 3.9698 * | ||

| Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | EST+ | 7.186 | 166.083 | 1.1525 | 3.1309 ** | ||

| Sphinganine | C18H39NO2 | EST+ | 15.967 | 302.3035 | 1.1289 | 11.1349 * | ||

| Uridine diphosphate glucose | C15H24N2O17P2 | EST− | 3.739 | 565.0413 | 1.3973 | 1.6738 ** | ||

| MAEC | all-trans-Retinoic acid | C20H28O2 | EST+ | 16.648 | 301.2169 | 1.0836 | 28.7524 * | |

| 4′-Phosphopantothenoylcysteine | C12H23N2O9PS | EST− | 16.728 | 401.0863 | 1.0771 | 1.6261 * | ||

| 1-Methylxanthine | C6H6N4O2 | EST− | 19.145 | 165.0392 | 1.2266 | 1.2591 * | ||

| Huvecs | Choline | C5H14NO | EST+ | 2.135 | 104.1063 | 1.5907 | 6.0157 * | |

| Sphingosine | C18H37NO2 | EST+ | 16.601 | 300.2878 | 1.8422 | 0.7391 ** | ||

| Eicosapentaenoic acid | C20H30O2 | EST+ | 16.838 | 303.2281 | 2.0591 | 13.4526 ** | ||

| Isocitric acid | C6H8O7 | EST− | 11.081 | 191.0169 | 1.2282 | 16.0554 * | ||

| Arachidonic acid | C20H32O2 | EST− | 19.186 | 303.2271 | 1.6681 | 0.7465 * | ||

| Palmitic acid | C16H32O2 | EST− | 19.708 | 255.2294 | 1.7891 | 0.7148 * |

| Inducer | Cell | Metabolites | Formula | SM | RT | m/z | VIP | FC (AEE/M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuSO4 | BAEC | LysoPC(16:0/0:0) | C24H50NO7P | EST+ | 19.8 | 496.3367 | 1.7987 | 0.7937 * |

| Phytosphingosine | C18H39NO3 | EST+ | 3.122 | 318.2987 | 1.752 | 3.0271 ** | ||

| 3-Dehydrosphinganine | C18H37NO2 | EST+ | 16.576 | 300.2889 | 1.001 | 0.8109 * | ||

| Phenylethylamine | C8H11N | EST+ | 0.102 | 122.0952 | 1.3499 | 7.0647 ** | ||

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | EST− | 18.996 | 137.0237 | 1.6976 | 0.0541 *** | ||

| Palmitic acid | C16H32O2 | EST− | 19.707 | 255.2305 | 1.7083 | 0.7595 ** | ||

| MAEC | Choline | C5H14NO | EST+ | 2.61 | 104.1059 | 1.8884 | 6.6366 ** | |

| 4′-Phosphopantothenoylcysteine | C12H23N2O9PS | EST− | 18.57 | 401.0835 | 1.7491 | 11.6252 *** | ||

| Uridine 5′-monophosphate | C9H13N2O9P | EST− | 5.383 | 323.0242 | 1.0491 | 0.8200 ** | ||

| 6-Methylmercaptopurine | C6H6N4S | EST− | 17.848 | 165.0189 | 1.4829 | 1.2122 * | ||

| Huvecs | Choline | C5H14NO | EST+ | 2.102 | 104.1061 | 1.3179 | 1.3354 * | |

| Hypoxanthine | C5H4N4O | EST+ | 2.434 | 137.0453 | 1.6656 | 0.1555 * | ||

| Homovanillin | C9H10O3 | EST− | 15.6 | 165.0539 | 1.4198 | 5.8969 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, J.; Tao, Q.; Li, M.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Yu, Q.-F.; Li, J.-Y. Multicellular Model Reveals the Mechanism of AEE Alleviating Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury via Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020877

Feng J, Tao Q, Li M-Z, Zhang Z-J, Yu Q-F, Li J-Y. Multicellular Model Reveals the Mechanism of AEE Alleviating Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury via Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020877

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Ji, Qi Tao, Meng-Zhen Li, Zhi-Jie Zhang, Qin-Fang Yu, and Jian-Yong Li. 2026. "Multicellular Model Reveals the Mechanism of AEE Alleviating Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury via Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020877

APA StyleFeng, J., Tao, Q., Li, M.-Z., Zhang, Z.-J., Yu, Q.-F., & Li, J.-Y. (2026). Multicellular Model Reveals the Mechanism of AEE Alleviating Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury via Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020877