Cycloastragenol Improves Fatty Acid Metabolism Through NHR-49/FAT-7 Suppression and Potent AAK-2 Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans Obesity Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

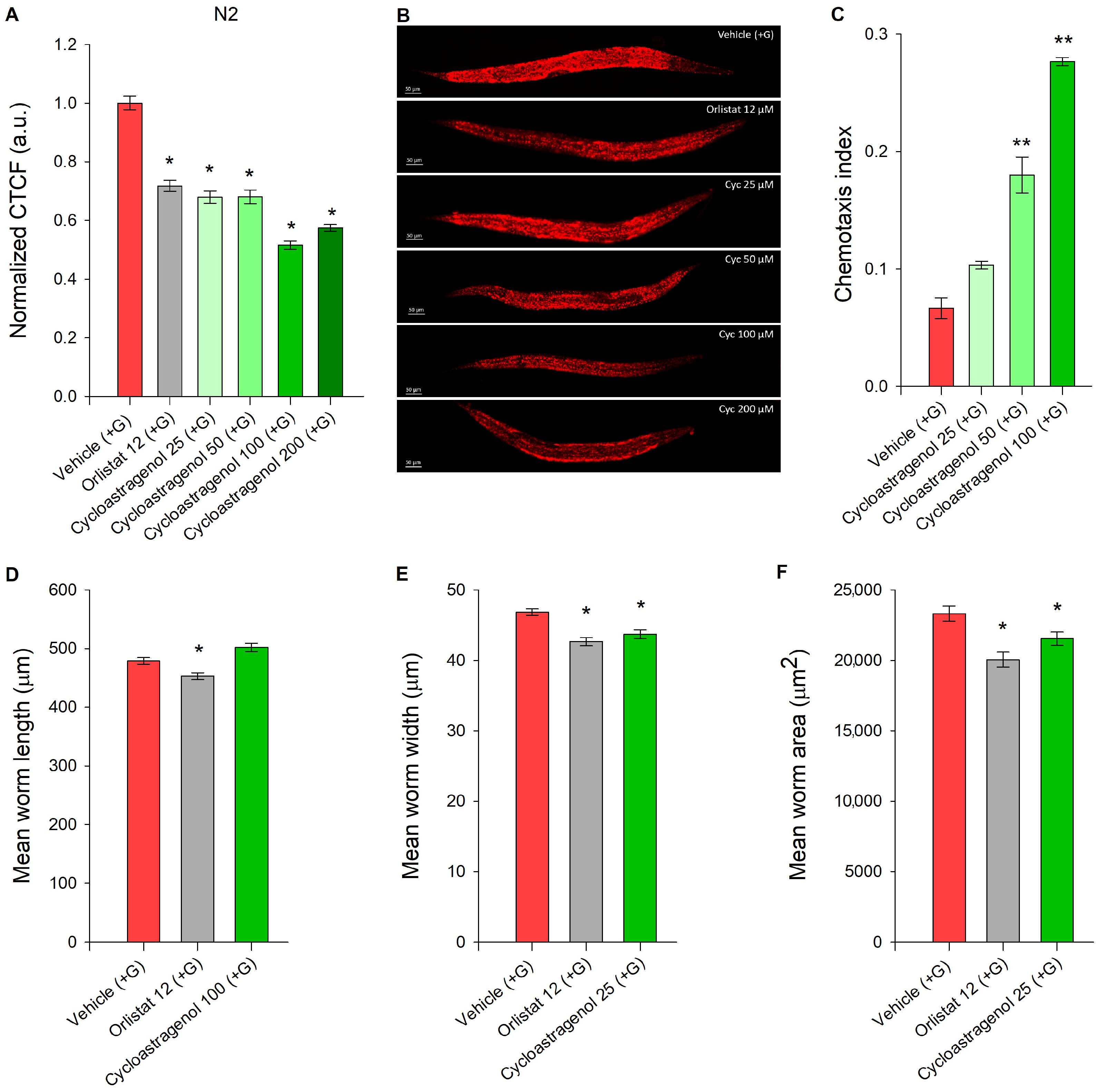

2.1. Cycloastragenol Diminished Glucose-Induced Lipid Accumulation in C. elegans

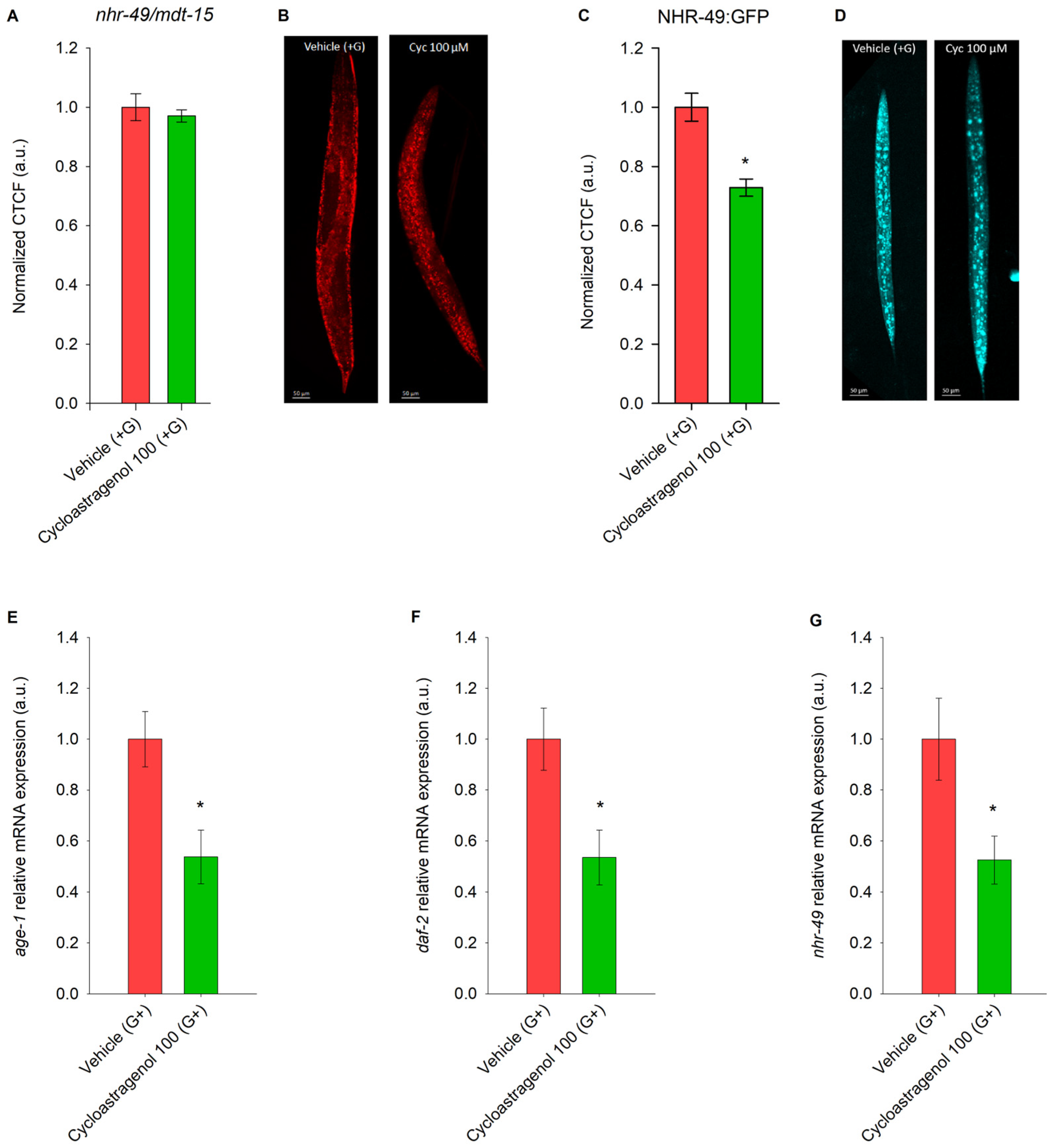

2.2. Cycloastragenol Downregulates NHR-49/MDT-15 Signaling in C. elegans

2.3. Cycloastragenol Activates AAK-2/SIR-2.1-Mediated Energy Regulation and Intestinal Mitochondria Dynamics in Obesity Model in C. elegans

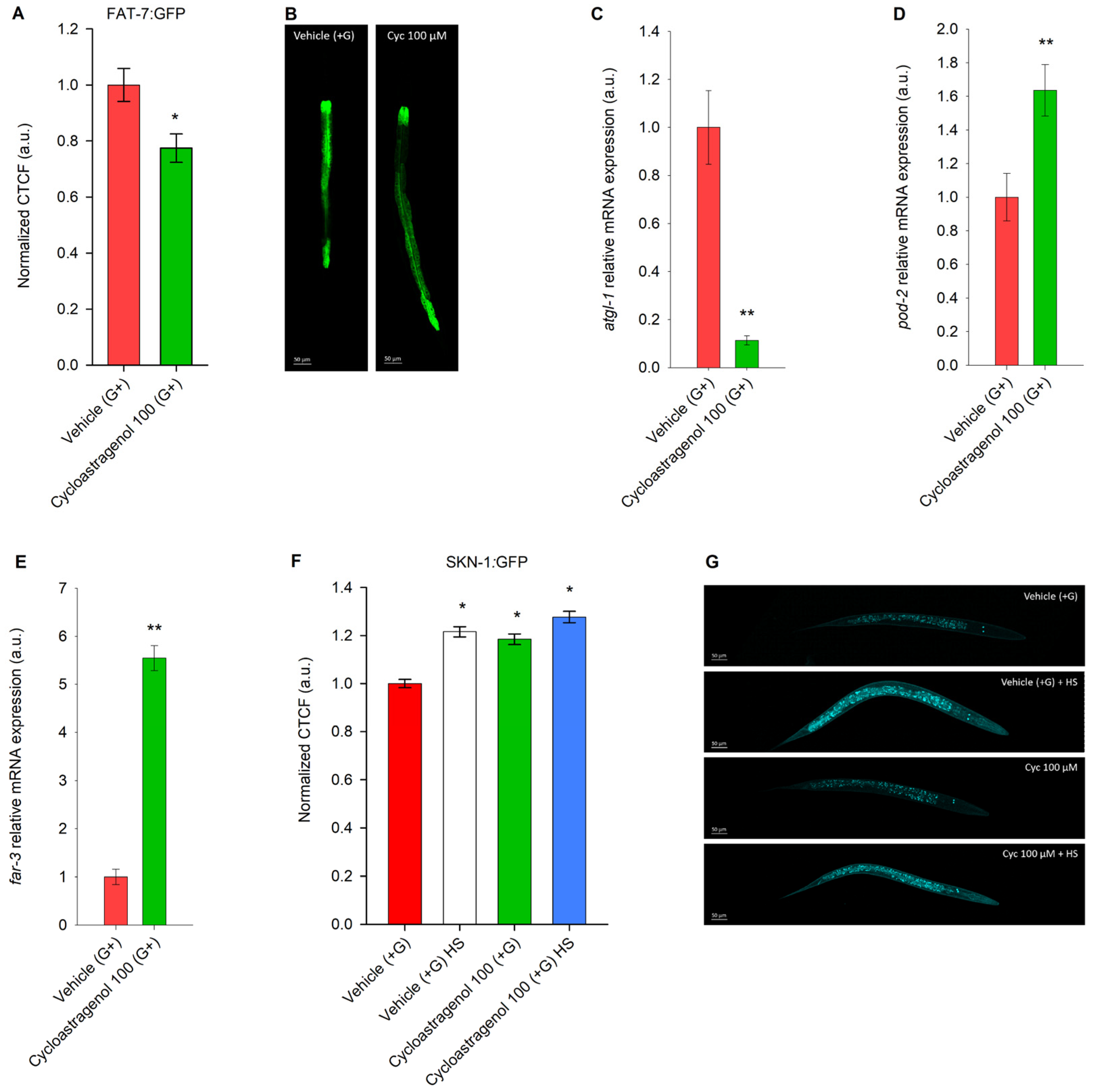

2.4. Cycloastragenol Acts as a far-3 Enhancer and Potent Inhibitor of FAT-7 to Modulate Fatty Acid Metabolism

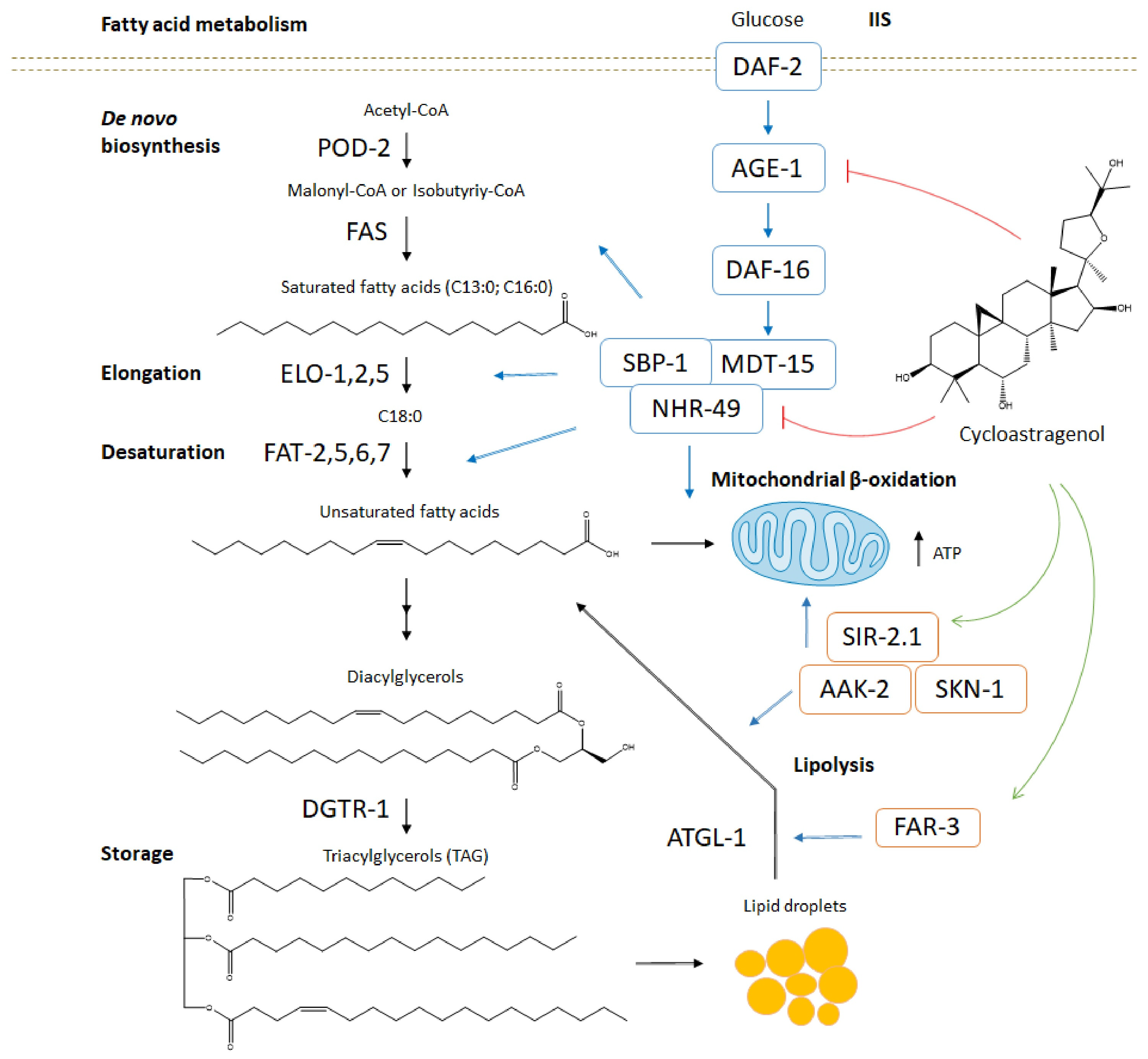

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Caenorhabditis Elegans: Maintenance and Treatment

4.3. Lipid Accumulation Assay

4.4. Chemotaxis Assay

4.5. Phenotype Analysis

4.6. Gene Expression Analysis Through RT-qPCR

4.7. Confocal Imaging of Reporter Transgenic Strains

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kivimäki, M.; Strandberg, T.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Frank, P.; Jokela, M.; Ervasti, J.; Suominen, S.B.; Vahtera, J.; Sipilä, P.N.; et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: An observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, N.H.; Singleton, R.K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J.E.; Paciorek, C.J.; Lhoste, V.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Stevens, G.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, P.; Bernard, S.; Appelsved, L.; Fu, K.; Andersson, D.P.; Salehpour, M.; Thorell, A.; Rydén, M.; Spalding, K.L. Adipose lipid turnover and long-term changes in body weight. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1385–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magkos, F.; Sørensen, T.I.A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Dhurandhar, N.V.; Loos, R.J.F.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Clemmensen, C.; Hjorth, M.F.; Allison, D.B.; Taubes, G.; et al. On the pathogenesis of obesity: Causal models and missing pieces of the puzzle. Nature Met. 2024, 6, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Khandelwal, R.; Wolfrum, C. Futile lipid cycling: From biochemistry to physiology. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.D.; Blüher, M.; Tschöp, M.H. Anti-obesity drug discovery: Advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusminski, C.M.; Perez-Tilve, D.; Müller, T.D.; DiMarchi, R.D.; Tschöp, M.H.; Scherer, P.E. Transforming obesity: The advancement of multi-receptor drugs. Cell 2024, 187, 3829–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezawork-Geleta, A.; Devereux, C.J.; Keenan, S.N.; Lou, J.; Cho, E.; Nie, S.; De Souza, D.P.; Narayana, V.K.; Siddall, N.A.; Rodrigues, C.H.M.; et al. Proximity proteomics reveals a mechanism of fatty acid transfer at lipid droplet-mitochondria- endoplasmic reticulum contact sites. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Tian, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, J.; Wei, X.; Qu, Q.; Yu, Y.; et al. Low-dose metformin targets the lysosomal AMPK pathway through PEN2. Nature 2022, 603, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savova, M.S.; Mihaylova, L.V.; Tews, D.; Wabitsch, M.; Georgiev, M.I. Targeting PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthymiou, V.; Ding, L.; Balaz, M.; Sun, W.; Balazova, L.; Straub, L.G.; Dong, H.; Simon, E.; Ghosh, A.; Perdikari, A.; et al. Inhibition of AXL receptor tyrosine kinase enhances brown adipose tissue functionality in mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingelhuber, F.; Frendo-Cumbo, S.; Omar-Hmeadi, M.; Massier, L.; Kakimoto, P.; Taylor, A.J.; Couchet, M.; Ribicic, S.; Wabitsch, M.; Messias, A.C.; et al. A spatiotemporal proteomic map of human adipogenesis. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.W.; Ponomarova, O.; Lee, Y.; Zhang, G.; Giese, G.E.; Walker, M.; Roberto, N.M.; Na, H.; Rodrigues, P.R.; Curtis, B.J.; et al. C. elegans as a model for inter-individual variation in metabolism. Nature 2022, 607, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnik, C.; Kaletsky, R.; Ashraf, J.M.; Sohrabi, S.; Cota, V.; Sengupta, T.; Keyes, W.; Luo, S.; Murphy, C.T. Enhanced branched-chain amino acid metabolism improves age-related reproduction in C. elegans. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.L. Fat synthesis and adiposity regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyanfif, A.; Jayarathne, S.; Koboziev, I.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a model organism to study metabolic effects of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in obesity. Adv. Nutrit. 2019, 10, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Meng, X.; Wang, C.; Dai, W.; Luo, Z.; Yin, Z.; Ju, Z.; Fu, X.; Yang, J.; Ye, Q.; et al. Histone H3K4me3 modification is a transgenerational epigenetic signal for lipid metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Long, S.; Yang, H.; Wu, J.; Li, M.; Tian, X.; Wei, X.; et al. Lithocholic acid binds TULP3 to activate sirtuins and AMPK to slow down ageing. Nature 2024, 643, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ravi Singh, J. Iron-deplete diet enhances Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan via oxidative stress response pathways. EMBO J. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savova, M.S.; Todorova, M.N.; Apostolov, A.G.; Yahubyan, G.T.; Georgiev, M.I. Betulinic acid counteracts the lipid accumulation in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulation of nhr-49 expression. Biomed. Pharmacoth. 2022, 156, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, M.N.; Savova, M.S.; Mihaylova, L.V.; Georgiev, M.I. Punica granatum L. leaf extract enhances stress tolerance and promotes healthy longevity through HLH-30/TFEB, DAF16/FOXO, and SKN1/NRF2 crosstalk in Caenorhabditis elegans. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 155971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, A.; Kitopoulou, K.; Borbolis, F.; Ploumi, C.; Gianniou, D.D.; Li, Z.; He, H.; Tsakiri, E.; Borland, H.; Kostakis, I.K.; et al. Urolithin A modulates inter-organellar communication via calcium-dependent mitophagy to promote healthy ageing. Autophagy 2025, 21, 3097–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chu, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, J.; Wang, P.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Z. Atractylenolide III mitigates Alzheimer’s disease by enhancing autophagy via the YY1-TFEB pathway. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 4474–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palikaras, K.; Lionaki, E.; Tavernarakis, N. Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, S.; Dou, B.; Zou, Y.; Han, H.; Liu, D.; Ke, Z.; Wang, Z. Cycloastragenol upregulates SIRT1 expression, attenuates apoptosis and suppresses neuroinflammation after brain ischemia. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Ma, Y.; Aroian, R.V.; Peng, D.; Sun, M. C. elegans monitor energy status via the AMPK pathway to trigger innate immune responses against bacterial pathogens. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Duan, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, H.; Ma, T.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, J.; Tian, F.; Wang, G.; et al. A feedback loop engaging propionate catabolism intermediates controls mitochondrial morphology. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, C.; Houriet, J.; Kellenberger, A.; Moser, C.; Balazova, L.; Balaz, M.; Dong, H.; Horvath, A.; Reinisch, I.; Efthymiou, V.; et al. Genkwanin glycosides are major active compounds in Phaleria nisidai extract mediating improved glucose homeostasis by stimulating glucose uptake into adipose tissues. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, C.; Yu, S.; Fan, Q.; Yang, K.; Huang, J.; Li, Y. Hickory nut polyphenols enhance oxidative stress resilience and improve the longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans through modulating DAF-16/DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 signaling. Phytomedicine 2025, 143, 156918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Tuerdi, N.; Ye, M.; Qi, R. Preventive effects of astragaloside IV and its active sapogenin cycloastragenol on cardiac fibrosis of mice by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 833, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jia, M.; Luo, J.; An, Y.; Chen, Z.; Bao, Y. Investigation of the lipid-lowering activity and mechanism of three extracts from Astragalus membranaceus, Hippophae rhamnoides L., and Taraxacum mongolicum Hand. Mazz based on network pharmacology and in vitro and in vivo experiments. Foods 2024, 13, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Li, Y.; Qin, H.; Zuo, C.; Zhou, C.; Xu, D. Cycloastragenol protects against glucocorticoid-induced osteogenic differentiation inhibition by activating telomerase. Phytother. Res. 2020, 35, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, K.; Che, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, K.; Zhang, G.; Yao, J.; Wang, J. A comprehensive review of cycloastragenol: Biological activity, mechanism of action and structural modifications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2022, 5, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Bedir, E.; Kirmizibayrak, P.B. The role of cycloastragenol at the intersection of NRF2/ARE, telomerase, and proteasome activity. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2022, 188, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Cao, S.; Cai, H.; Zhao, Z.; Song, Y. Cycloastragenol ameliorates experimental heart damage in rats by promoting myocardial autophagy via inhibition of AKT1-RPS6KB1 signalling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, K.D.; Erisik, D.; Taskiran, D.; Turhan, K.; Kose, T.; Cetin, E.O.; Sendemir, A.; Uyanikgil, Y. Protective effects of E-CG-01 (3,4-lacto cycloastragenol) against bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in C57BL/6 mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, F.; Jia, L.; Li, H. Cycloastragenol induces apoptosis and protective autophagy through AMPK/ULK1/mTOR axis in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 22, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Kumar, V.; Khan, A.M.; Joo, M.; Lee, K.; Sohn, S.; Kong, I. Cycloastragenol activation of telomerase improves β-Klotho protein level and attenuates age-related malfunctioning in ovarian tissues. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2022, 209, 111756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, S.; Yang, L.; Ji, G.; Tong, Q.; et al. Cycloastragenol improves hepatic steatosis by activating farnesoid X receptor signalling. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 121, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Cycloastragenol regulates mitochondrial homeostasis–mediated renal tubular injury to ameliorate diabetic kidney disease by directly targeting ERK to modulate TFEB. Phytother. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savova, M.S.; Vasileva, L.V.; Mladenova, S.G.; Amirova, K.M.; Ferrante, C.; Orlando, G.; Wabitsch, M.; Georgiev, M.I. Ziziphus jujuba Mill. leaf extract restrains adipogenesis by targeting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savova, M.S.; Todorova, M.N.; Binev, B.K.; Georgiev, M.I.; Mihaylova, L.V. Curcumin enhances the anti-obesogenic activity of orlistat through SKN-1/NRF2-dependent regulation of nutrient metabolism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Jeong, D.; Son, H.G.; Yamaoka, Y.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.; Khan, A.A.; Roh, T.; Moon, D.W.; Lee, Y.; et al. SREBP and MDT-15 protect C. elegans from glucose-induced accelerated aging by preventing accumulation of saturated fat. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2490–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.; Bodhicharla, R.; Ståhlman, M.; Svensk, E.; Busayavalasa, K.; Palmgren, H.; Ruhanen, H.; Boren, J.; Pilon, M. Evolutionarily conserved long-chain Acyl-CoA synthetases regulate membrane composition and fluidity. eLife 2019, 8, e47733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmeisser, S.; Priebe, S.; Groth, M.; Monajembashi, S.; Hemmerich, P.; Guthke, R.; Platzer, M.; Ristow, M. Neuronal ROS signalling rather than AMPK/sirtuin-mediated energy sensing links dietary restriction to lifespan extension. Mol. Metab. 2013, 2, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, L.; Fu, X.; Chen, J.; Ma, J. Application of Caenorhabditis elegans in lipid metabolism research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Kwon, S.; Ham, S.; Lee, D.; Park, H.H.; Yamaoka, Y.; Jeong, D.; Artan, M.; Altintas, O.; Park, S.; et al. Caenorhabditis elegans Lipin 1 moderates the lifespan-shortening effects of dietary glucose by maintaining ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiang, J.; Qi, Z.; Du, M. Plant extracts in prevention of obesity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 2221–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, B.B.; Schneeberger, K.; Vera, E.; Tejera, A.; Harley, C.B.; Blasco, M.A. The telomerase activator TA-65 elongates short telomeres and increases health span of adult/old mice without increasing cancer incidence. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Du, M.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Y.; Luo, S.; Hu, W.; et al. Cycloastragenol prevents age-related bone loss: Evidence in d-galactose-treated and aged rats. Biomed. Pharmacoth. 2020, 128, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T. Cycloastragenol restrains keratinocyte hyperproliferation by promoting autophagy via the miR-145/STC1/Notch1 axis in psoriasis. Immunopharmacol. Immunotox. 2024, 46, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.T.; Kim, C.; Lee, J.H.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Shair, O.H.; Sethi, G.; Ahn, K.S. Cycloastragenol can negate constitutive STAT3 activation and promote paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Phytomedicine 2019, 59, 152907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, N.J. Dietary safety of cycloastragenol from Astragalus spp.: Subchronic toxicity and genotoxicity studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 64, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, C.B.; Liu, W.; Flom, P.L.; Raffaele, J.M. A natural product telomerase activator as part of a health maintenance program: Metabolic and cardiovascular response. Rejuv. Res. 2013, 16, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Shen, P.; Chang, A.L.; Qi, W.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.; Park, Y. trans-Trismethoxy resveratrol decreased fat accumulation dependent on fat-6 and fat-7 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4966–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Kingsley, S.; Walker, G.; Mondoux, M.A.; Tissenbaum, H.A. Metabolic shift from glycogen to trehalose promotes lifespan and healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2791–E2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibshman, J.D.; Doan, A.E.; Moore, B.T.; Kaplan, R.E.; Hung, A.; Webster, A.K.; Bhatt, D.P.; Chitrakar, R.; Hirschey, M.D.; Baugh, L.R. daf-16/FoxO promotes gluconeogenesis and trehalose synthesis during starvation to support survival. eLife 2017, 6, e30057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, V.; Todorova, M.N.; Savova, M.S.; Ivanov, K.; Georgiev, M.I.; Ivanova, S. Maral root extract and its main constituent 20-hydroxyecdysone enhance stress resilience in Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mihaylova, L.V.; Savova, M.S.; Todorova, M.N.; Tonova, V.; Binev, B.K.; Georgiev, M.I. Cycloastragenol Improves Fatty Acid Metabolism Through NHR-49/FAT-7 Suppression and Potent AAK-2 Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans Obesity Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020772

Mihaylova LV, Savova MS, Todorova MN, Tonova V, Binev BK, Georgiev MI. Cycloastragenol Improves Fatty Acid Metabolism Through NHR-49/FAT-7 Suppression and Potent AAK-2 Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans Obesity Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020772

Chicago/Turabian StyleMihaylova, Liliya V., Martina S. Savova, Monika N. Todorova, Valeria Tonova, Biser K. Binev, and Milen I. Georgiev. 2026. "Cycloastragenol Improves Fatty Acid Metabolism Through NHR-49/FAT-7 Suppression and Potent AAK-2 Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans Obesity Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020772

APA StyleMihaylova, L. V., Savova, M. S., Todorova, M. N., Tonova, V., Binev, B. K., & Georgiev, M. I. (2026). Cycloastragenol Improves Fatty Acid Metabolism Through NHR-49/FAT-7 Suppression and Potent AAK-2 Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans Obesity Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020772