Investigating the Molecular Mechanisms of the Anticancer Effects of Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde Against Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cells In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

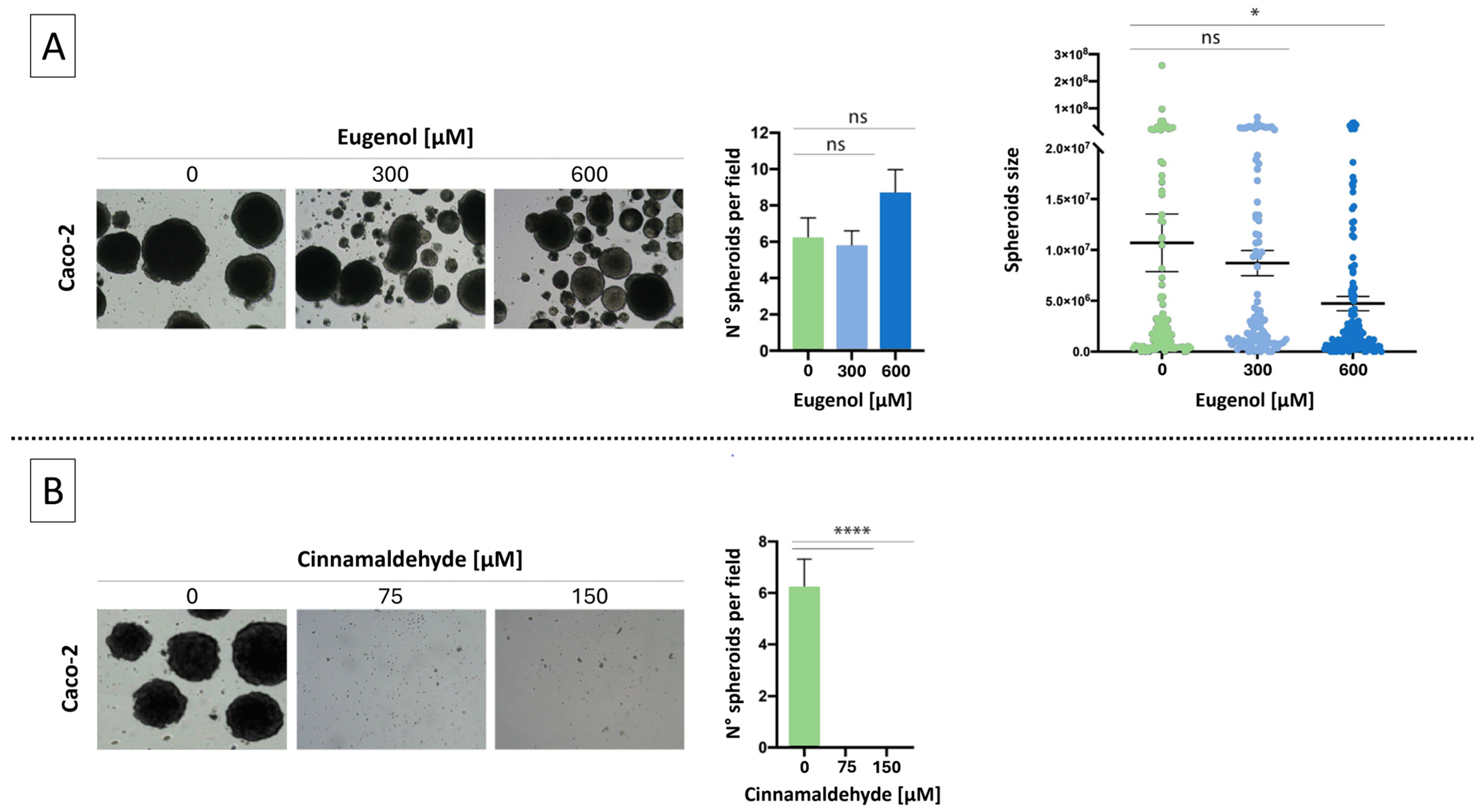

2.1. Effects of EU and CN on Spheroid Growth

2.2. Effect of EU and CN Co-Administration on the Metabolic Activity of CRC Cells

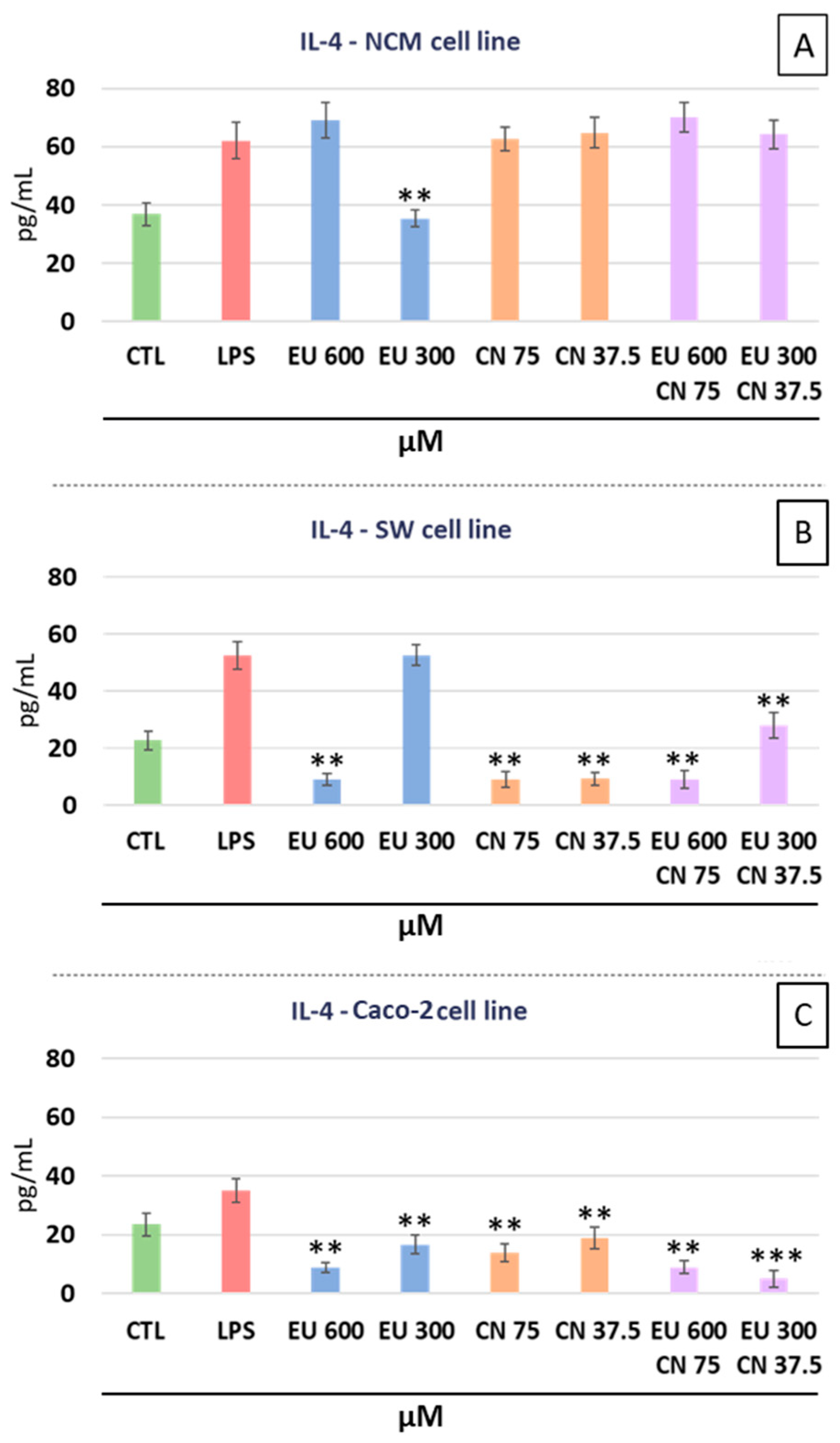

2.3. Cytokines Analysis

2.4. Transcriptome Analysis

2.5. NCM-460—Overrepresentation Analysis

2.6. SW-620 Overrepresentation Analysis

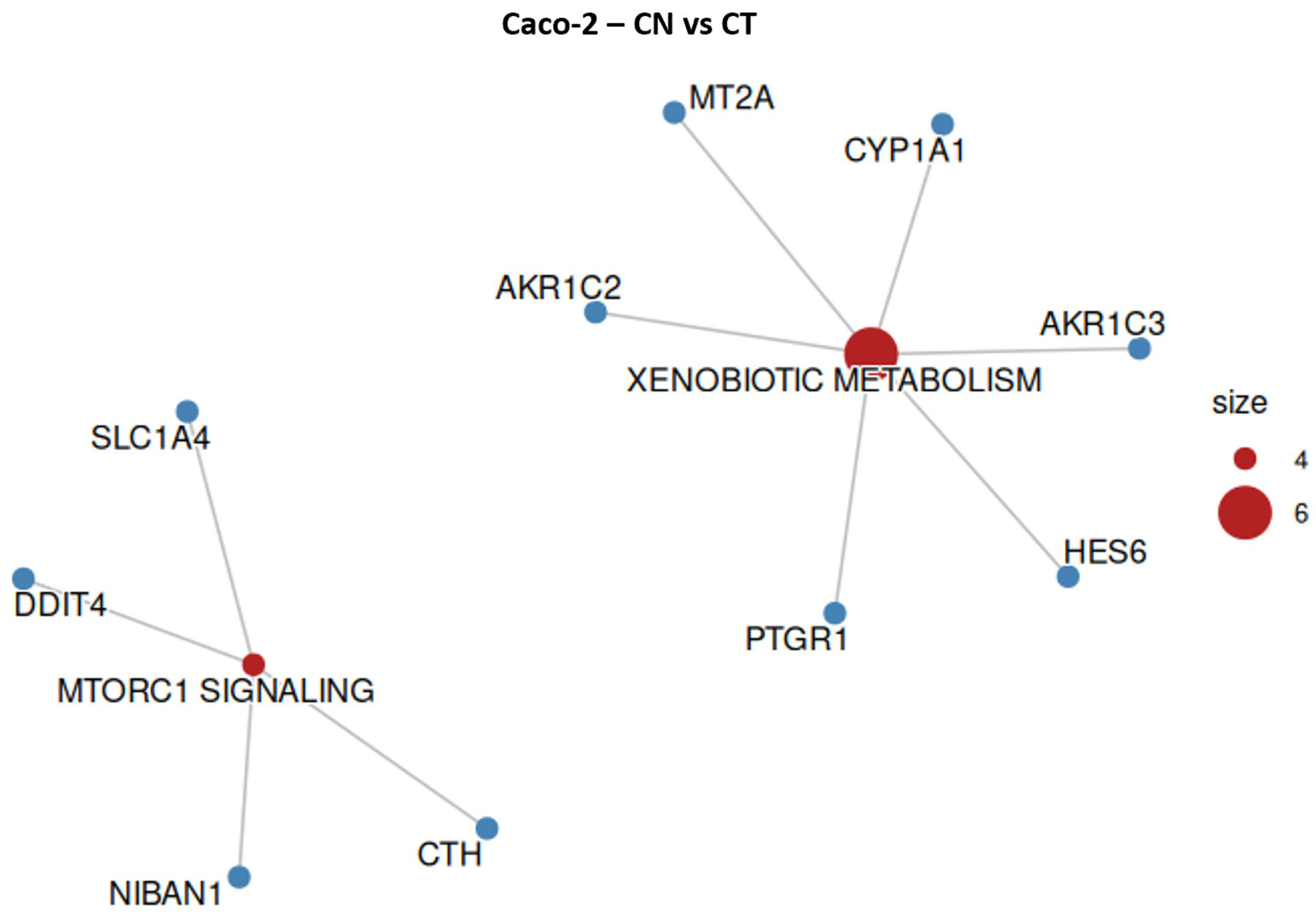

2.7. Caco-2 Overrepresentation Analysis

2.8. Western Blotting

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell Cultures

4.3. Cell Treatments

4.4. Clonogenic Cell Survival Assay

4.5. Cell Viability Assay

4.6. Cytokine Analysis

4.7. Transcriptome Analysis

- Quality control of the reads: Quality assessment of the raw sequencing data was performed using the FastQC tool, which calculated Phred scores to evaluate the probability of base-calling errors. Quality control metrics, such as per-base sequence quality, were summarized and visualized using the FastQC report [67].

- Adapter and short read removal: Adapter sequences and reads shorter than 25 nucleotides were removed using the bioinformatics tool cutadapt (version 2.5) [68]. Although no adapter sequences were detected, this step was performed to eliminate very short reads and improve the overall quality of mapping.

- Read alignment and quantification: Reads were aligned to the Homo sapiens reference genome (GRCh38.p13) [69] using STAR software (version 2.7.10b) [70]. The alignment was performed using default settings for paired-end reads, and multi-mapping and gap tolerance parameters were kept at their default values. Transcript quantification was performed using the FeatureCounts algorithm to calculate read counts mapped to genomic features, including genes and exons.

- Differential expression analysis: R software (version 4.5.0) was used to create a matrix of all expressed transcripts with corresponding read counts. Data were normalized using the RSEM method to ensure consistency across samples. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the Bioconductor package NOISeq-Sim, a non-parametric method suitable for nonreplicated samples [71].

4.7.1. Criteria for Differential Gene Selection

4.7.2. Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA)

4.8. Western Blotting

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.-Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.-B.; Sheng, J.-P.; Xu, B. Signaling Pathways Involved in Colorectal Cancer: Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellinaro, R.; Spoletini, D.; Grieco, M.; Avella, P.; Cappuccio, M.; Troiano, R.; Lisi, G.; Garbarino, G.M.; Carlini, M. Colorectal Cancer: Current Updates and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Fan, Y. Combined KRAS and TP53 Mutation in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Enhance Chemoresistance to Promote Postoperative Recurrence and Metastasis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, H.; Tang, D.W.T.; Wong, S.H.; Lal, D. Gut Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer: Biological Role and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2023, 15, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koveitypour, Z.; Panahi, F.; Vakilian, M.; Peymani, M.; Seyed Forootan, F.; Nasr Esfahani, M.H.; Ghaedi, K. Signaling Pathways Involved in Colorectal Cancer Progression. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, T.; Ruszkowska, M.; Danielewicz, A.; Niedźwiedzka, E.; Arłukowicz, T.; Przybyłowicz, K.E. A Review of Colorectal Cancer in Terms of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel, G.; Ghasemi-Kebria, F.; Malekzadeh, R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers 2024, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boute, T.C.; Swartjes, H.; Greuter, M.J.E.; Elferink, M.A.G.; Van Eekelen, R.; Vink, G.R.; De Wilt, J.H.W.; Coupé, V.M.H. Cumulative Incidence, Risk Factors, and Overall Survival of Disease Recurrence after Curative Resection of Stage II–III Colorectal Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaderi, S.M.; Galjart, B.; Verhoef, C.; Slooter, G.D.; Koopman, M.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; de Wilt, J.H.W.; van Erning, F.N. Disease Recurrence after Colorectal Cancer Surgery in the Modern Era: A Population-Based Study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2399–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiong, X.; Liu, X.; Lin, B.; Xu, B. Recent Advances of Pathomics in Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1094869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ji, Q.; Li, Q. Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapies in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Underlying Mechanisms and Reversal Strategies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, P.W.; Ruff, S.M.; Pawlik, T.M. Update on Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2024, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzoli, S.; Alarcón-Zapata, P.; Seitimova, G.; Alarcón-Zapata, B.; Martorell, M.; Sharopov, F.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Dize, D.; Yamthe, L.R.T.; Les, F.; et al. Natural Essential Oils as a New Therapeutic Tool in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spisni, E.; Petrocelli, G.; Imbesi, V.; Spigarelli, R.; Azzinnari, D.; Donati Sarti, M.; Campieri, M.; Valerii, M.C. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Microbial-Modulating Activities of Essential Oils: Implications in Colonic Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, N.; Mantha, A.K.; Mittal, S. Essential Oils and Their Constituents as Anticancer Agents: A Mechanistic View. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 154106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocelli, G.; Farabegoli, F.; Valerii, M.C.; Giovannini, C.; Sardo, A.; Spisni, E. Molecules Present in Plant Essential Oils for Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer (CRC). Molecules 2021, 26, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambuy, Y.; De Angelis, I.; Ranaldi, G.; Scarino, M.L.; Stammati, A.; Zucco, F. The Caco-2 Cell Line as a Model of the Intestinal Barrier: Influence of Cell and Culture-Related Factors on Caco-2 Cell Functional Characteristics. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2005, 21, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.-Y.; Choung, S.Y.; Paik, I.-S.; Kang, H.-J.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, M.-O. Activation of NF-.KAPPA.B Determines the Sensitivity of Human Colon Cancer Cells to TNF.ALPHA.-Induced Apoptosis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 23, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainaldi, G.; Boe, A. Sandra Gessani 3D (Three-Dimensional) Caco-2 Spheroids: Optimized in Vitro Protocols to Favor Their Differentiation Process and to Analyze Their Cell Growth Behavior. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 4, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Kwon, S.; Kim, K.S. Challenges of Applying Multicellular Tumor Spheroids in Preclinical Phase. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, S.K.; Mazumdar, A.; Mondhe, D.; Mandal, M. Apoptotic Effect of Eugenol in Human Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Cell Biol. Int. 2011, 35, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, N.C.; Nawas, M.I.; Poole, C.F. Evaluation of a Reversed-Phase Column (Supelcosil LC-ABZ) under Isocratic and Gradient Elution Conditions for Estimating Octanol–Water Partition Coefficients. Analyst 2003, 128, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A.; Hoekman, D. Exploring QSAR—Hydrophobic, Electronic, and Steric Constants; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Rao, L.J.; Sakariah, K.K. Chemical Composition of Volatile Oil from Cinnamomum Zeylanicum Buds. Z. Naturforschung C 2002, 57, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francipane, M.G.; Perez Alea, M.; Lombardo, Y.; Todaro, M.; Medema, J.P.; Stassi, G. Crucial Role of Interleukin-4 in the Survival of Colon Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4022–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzichetto, C.; Milella, M.; Zampiva, I.; Simionato, F.; Amoreo, C.A.; Buglioni, S.; Pacelli, C.; Le Pera, L.; Colombo, T.; Bria, E.; et al. Interleukin-8 in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Its Potential Role as a Prognostic Biomarker. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.E.; Simmons, J.G.; Ding, S.; Van Landeghem, L.; Lund, P.K. Cytokine Induction of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 2 Is Mediated by STAT3 in Colon Cancer Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 1718–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoiliqy, M.; Wen, J.; Xu, B.; Sun, Y.; Lian, M.; Li, Y.; Qaed, E.; Al-Azab, M.; Chen, D.; Shopit, A.; et al. Cinnamaldehyde Protects against Rat Intestinal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injuries by Synergistic Inhibition of NF-κB and P53. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.-X.; Zhong, S.; Meng, X.-B.; Zheng, N.-Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qin, L.; Wang, X.-L. Cinnamaldehyde Inhibits Inflammation of Human Synoviocyte Cells Through Regulation of Jak/Stat Pathway and Ameliorates Collagen-Induced Arthritis in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 373, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, S.; Alkholiwy, E.M.A.; Ali Ahmed, S.O.; Aljurf, M.; Al-Hejailan, R.; Aboussekhra, A. Eugenol Promotes Apoptosis in Leukemia Cells via Targeting the Mitochondrial Biogenesis PPRC1 Gene. Cells 2025, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, D.; Militão, G.; De Morais, M.; De Sousa, D. The Dual Antioxidant/Prooxidant Effect of Eugenol and Its Action in Cancer Development and Treatment. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Lin, Q.; Gu, Y.; Yu, W. Eugenol Protects Cells against Oxidative Stress via Nrf2. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 21, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.-P.; Oseini, A.M.; Moser, C.D.; Yu, C.; Elsawa, S.F.; Hu, C.; Nakamura, I.; Han, T.; Aderca, I.; Isomoto, H.; et al. The Oncogenic Effect of Sulfatase 2 in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Mediated in Part by Glypican 3-Dependent Wnt Activation. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1680–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shang, C.; Gai, X.; Song, T.; Han, S.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, X. Sulfatase 2-Induced Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression via Inhibition of Apoptosis and Induction of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 631931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, H.; Cui, X.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J. uPAR: An Essential Factor for Tumor Development. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 7026–7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.W.; Marshall, C.J. Regulation of Cell Signalling by uPAR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulding, T.; Wu, F.; McCuaig, R.; Dunn, J.; Sutton, C.R.; Hardy, K.; Tu, W.; Bullman, A.; Yip, D.; Dahlstrom, J.E.; et al. Differential Roles for DUSP Family Members in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cell Regulation in Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, H.; Han, B. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition-Mediated Tumor Therapeutic Resistance. Molecules 2022, 27, 4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Q.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, S. ATP6V0A4 as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattahi, F.; Saeednejad Zanjani, L.; Habibi Shams, Z.; Kiani, J.; Mehrazma, M.; Najafi, M.; Madjd, Z. High Expression of DNA Damage-Inducible Transcript 4 (DDIT4) Is Associated with Advanced Pathological Features in the Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, F.; Kiani, J.; Alemrajabi, M.; Soroush, A.; Naseri, M.; Najafi, M.; Madjd, Z. Overexpression of DDIT4 and TPTEP1 Are Associated with Metastasis and Advanced Stages in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Study Utilizing Bioinformatics Prediction and Experimental Validation. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Seok, J.; Saha, S.K.; Cho, S.; Jeong, Y.; Gil, M.; Kim, A.; Shin, H.Y.; Bae, H.; Do, J.T.; et al. Alterations and Co-Occurrence of C-MYC, N-MYC, and L-MYC Expression Are Related to Clinical Outcomes in Various Cancers. Int. J. Stem Cells 2023, 16, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, Z.E.; Walton, Z.E.; Altman, B.J.; Hsieh, A.L.; Dang, C.V. MYC, Metabolism, and Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hu, X.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Kong, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y. RPF2 Mediates the CARM1-MYCN Axis to Promote Chemotherapy Resistance in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 51, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerdt, B.G.; Molinas, S.; Deitch, D.; Augenlicht, L.H. Aggressive Subtypes of Human Colorectal Tumors Frequently Exhibit Amplification of the C-Myc Gene. Oncogene 1991, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; He, Y.; Shen, K.; Wang, K.; Shi, T.; Chen, W. NR4A1 Depletion Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Progression by Promoting Necroptosis via the RIG-I-like Receptor Pathway. Cancer Lett. 2024, 585, 216693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Tang, W.; Cheng, X. NR4A1 as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Colon Adenocarcinoma: A Computational Analysis of Immune Infiltration and Drug Response. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1181320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Lan, C.; Jiao, G.; Fu, W.; Long, X.; An, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Chen, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Therapeutic Inhibition of SGK1 Suppresses Colorectal Cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Kong, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Duan, X.; Sun, T.; Tao, Z.; Liu, W. SGK1 in Human Cancer: Emerging Roles and Mechanisms. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 608722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Yan, X.; Xiao, M.; Hao, J.; Alekseev, A.; Khong, H.; Chen, T.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis Identifies NR4A1 as a Key Mediator of T Cell Dysfunction. Nature 2019, 567, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Shin, K.-J.; Bae, S.; Seo, J.-M.; Jung, H.; Moon, Y.-A.; Yang, S.-G. Tumor-Mediated 4-1BB Induces Tumor Proliferation and Metastasis in the Colorectal Cancer Cells. Life Sci. 2022, 307, 120899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, A.N.; Yang, E.S. Beyond DNA Repair: Additional Functions of PARP-1 in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Beyer, A.; Aebersold, R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell 2016, 165, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, C.; Singh, A. Apoptosis: A Target for Anticancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Yu, Z.; Lu, T.; Peng, W.; Gong, Y.; Chen, C. PARP1 Bound to XRCC2 Promotes Tumor Progression in Colorectal Cancer. Discov. Onc. 2024, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, P.; Thibol, L.; Lemsch, A.; Potlitz, F.; Schulig, L.; Grathwol, C.; Manolikakes, G.; Schade, D.; Roukos, V.; Link, A.; et al. Targeting PARP-1 and DNA Damage Response Defects in Colorectal Cancer Chemotherapy with Established and Novel PARP Inhibitors. Cancers 2024, 16, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravizza, R.; Gariboldi, M.B.; Passarelli, L.; Monti, E. Role of the P53/P21 System in the Response of Human Colon Carcinoma Cells to Doxorubicin. BMC Cancer 2004, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamloo, B.; Usluer, S. P21 in Cancer Research. Cancers 2019, 11, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Jang, E.; Eom, Y.-W.; Yoon, G.; Choi, K.S.; Kim, E. Dual Role of P21 in Regulating Apoptosis and Mitotic Integrity in Response to Doxorubicin in Colon Cancer Cells. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, R.U.; Ng, P.; Sprengart, M.L.; Porter, A.G. Caspase-3 Is Required for α-Fodrin Cleavage but Dispensable for Cleavage of Other Death Substrates in Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 15540–15545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A Review of Programmed Cell Death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Q.; Li, F.; Li, C. Caspase-3 Regulates the Migration, Invasion and Metastasis of Colon Cancer Cells. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, C.; Rizzello, F.; Gionchetti, P.; Calafiore, A.; Pagano, N.; De Fazio, L.; Valerii, M.C.; Cavazza, E.; Strillacci, A.; Comelli, M.C.; et al. Can Supplementation of Phytoestrogens/Insoluble Fibers Help the Management of Duodenal Polyps in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis? CARCIN 2016, 37, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strillacci, A.; Griffoni, C.; Spisni, E.; Manara, M.C.; Tomasi, V. RNA Interference as a Key to Knockdown Overexpressed Cyclooxygenase-2 Gene in Tumour Cells. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 94, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, N.A.P.; Rodermond, H.M.; Stap, J.; Haveman, J.; Van Bree, C. Clonogenic Assay of Cells in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigarelli, R.; Calabrese, C.; Spisni, E.; Vinciguerra, S.; Saracino, I.M.; Dussias, N.K.; Filippone, E.; Valerii, M.C. Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) for Prevention of Gastroesophageal Inflammation: Insights from In Vitro Models. Life 2024, 14, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FastQC A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GENCODE. Available online: https://www.gencodegenes.org/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, S.; Furió-Tarí, P.; Turrà, D.; Pietro, A.D.; Nueda, M.J.; Ferrer, A.; Conesa, A. Data Quality Aware Analysis of Differential Expression in RNA-Seq with NOISeq R/Bioc Package. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, gkv711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Birger, C.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Ghandi, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Tamayo, P. The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Count | Genes | Fold Enrichment | Hallmark Gene Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | F10/PTGES/ABCC2/MT2A/ FABP1/PDK4/CYP1A1 | 3.066 | Xenobiotic Metabolism |

| 7 | CTSE/F10/C8G/MEP1A/ RAPGEF3/CRIP2/HMGCS2 | 5.44 | Coagulation |

| 6 | ACSL1/AQP7/FABP1/ HMGCS1/HMGCS2/CYP1A1 | 3.069 | Fatty Acid Metabolism |

| Gene Count | Genes | Fold Enrichment | Hallmark Gene Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | CYP1A1/FOSB | 5.746 | UV Response Up |

| 3 | CYP1A1/ALDH1A1/ ALDH3A1 | 8.619 | Fatty Acid Metabolism |

| Gene Count | Genes | Fold Enrichment | Hallmark Gene Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | AFAP1L2/LYPD3/ATP6V0A4/SRPX/ SLC2A4/MDGA1 | 6.966 | Apical surface |

| 12 | ICOSLG/TUBB2A/G0S2/CDKN1A/ TNFAIP2/GPR183/KLF9/IL18/KLF6/ NR4A1/SLC2A3/SGK1 | 2.896 | TNF-α Signaling via NF-kB |

| 10 | FGFR3/ATP2B4/SERPINA5/CA2/ OLFM1/CA12/HR/CYP26B1/PTGES/ SGK1 | 2.413 | Estrogen Response Late |

| 10 | TGM2/CDKN1A/CA12/IGFBP1/PGF/ MT1E/SRPX/PIM1/KLF6/SLC2A3 | 2.334 | Hypoxia |

| 9 | SLPI/G0S2/ADGRA2/PRKG2/CA2/ MYCN/TMEM158/KCNN4/GPRC5B | 2.447 | KRAS Signaling Up |

| 9 | CA2/PSMB9/HSPA1A/ADRA2B/FN1/ PIM1/CTSH/CTSL/WAS | 2.431 | Complement |

| 9 | TXNIP/PSMB9/CDKN1A/TNFAIP2/ PIM1/XAF1/NLRC5/UBE2L6/CD274 | 2.431 | Interferon-γ response |

| 9 | COL6A1/SOCS2/TGM2/CA2/GLIPR2/ CCNE1/PIM1/KLF6/SLC2A3 | 2.287 | IL2 STAT5 Signaling |

| 7 | FGFR3/ARHGDIG/LYPD3/COL2A1/ IDUA/TENT5C/SGK1 | 2.425 | KRAS Signaling Down |

| Gene Count | Genes | Fold Enrichment | Hallmark Gene Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | TNFRSF9/SCN1B | 6.844 | Inflammatory Response |

| 2 | TNFRSF9/CAPN3 | 5.507 | IL-2 STAT5 Signaling |

| Gene Count | Genes | Fold Enrichment | Hallmark Gene Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | CXCR4/CDKN1C/HS3ST1/ CCN1/PLIN2/NDRG1/PLAUR | 3.274 | Hypoxia |

| 9 | SH2B2/CAPN5/ACOX2/FGA/ GDA/PLAU/FYN/HMGCS2/ PLAT | 0.384 | Coagulation |

| 10 | SERPINA3/MICB/PAPSS2/ SERPINA5/SCNN1A/ACOX2/ IGFBP4/CA12/TRIM29/ HMGCS2 | 2.59 | Estrogen Response Late |

| 9 | LRRC15/COL8A2/IGFBP2/ CCN1/GEM/IGFBP4/COL6A2/ PLAUR/LOX | 2.597 | Mesenchymal Transition |

| 4 | ATP6V0A4/SULF2/PLAUR/ SRPX | 5.065 | Apical Surface |

| 9 | CCRL2/DUSP4/BCL6/CCN1/ GEM/ DUSP5/PLAU/PLAUR/FOSB | 2.292 | TNF-α Signaling via NF-kB |

| 8 | TGFB2/CYP2J2/PAPSS2/LCAT/ ACOX2/AKR1C2/IGFBP4/ CYP1A1 | 2.158 | Xenobiotic Metabolism |

| 7 | UBE2L6/ACSL1/ACSL5/CPT1A/MGLL/HMGCS2/CYP1A1 | 2.263 | Fatty Acid Metabolism |

| Gene Count | Genes | Fold Enrichment | Hallmark Gene Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | HES6/PTGR1/AKR1C3/ MT2A/CYP1A1/AKR1C2 | 6.272 | Xenobiotic Metabolism |

| 4 | DDIT4/NIBAN1/ CTH/SLC1A4 | 3.664 | MTORC1 Signaling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bernacchi, A.; Valerii, M.C.; Spigarelli, R.; Dussias, N.K.; Rizzello, F.; Spisni, E. Investigating the Molecular Mechanisms of the Anticancer Effects of Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde Against Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cells In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020649

Bernacchi A, Valerii MC, Spigarelli R, Dussias NK, Rizzello F, Spisni E. Investigating the Molecular Mechanisms of the Anticancer Effects of Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde Against Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cells In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020649

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernacchi, Alberto, Maria Chiara Valerii, Renato Spigarelli, Nikolas Kostantine Dussias, Fernando Rizzello, and Enzo Spisni. 2026. "Investigating the Molecular Mechanisms of the Anticancer Effects of Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde Against Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cells In Vitro" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020649

APA StyleBernacchi, A., Valerii, M. C., Spigarelli, R., Dussias, N. K., Rizzello, F., & Spisni, E. (2026). Investigating the Molecular Mechanisms of the Anticancer Effects of Eugenol and Cinnamaldehyde Against Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Cells In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020649