The Vaginal Microbiome and Host Health: Implications for Cervical Cancer Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

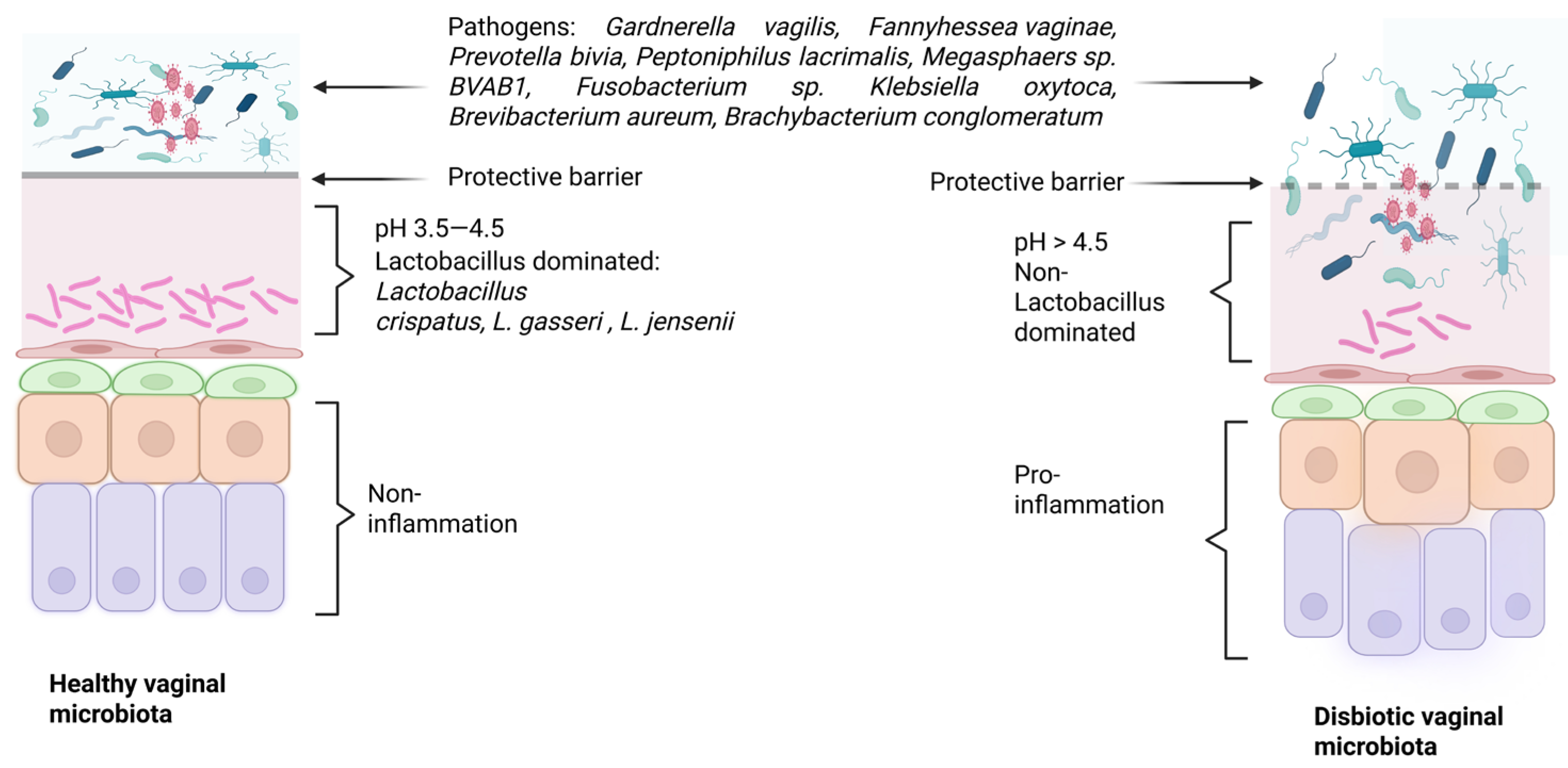

2. Vaginal Microbiome

2.1. Methods for Identifying the Vaginal Microbiome

2.1.1. Culture-Based Method

2.1.2. 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.2. Geographical and Individual Variation

2.3. Community State Type (CST) Classification

2.4. Lactobacillus-Mediated Protective Mechanisms

3. HPV and Microbiome

3.1. HPV Mechanism and Host Immunity

3.2. Microbiome Shifts During CIN Progression

3.3. The Use of Probiotics (Lactobacillus) as Treatment

3.3.1. Oral Administration

3.3.2. Vaginal Administration

4. Microbiome in the Mexican Population

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ursell, L.K.; Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, S38–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckburg, P.B.; Bik, E.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Purdom, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Sargent, M.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Relman, D.A. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 2005, 308, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilber-Rosenberg, I.; Rosenberg, E. Role of Microorganisms in the Evolution of Animals and Plants: The Hologenome Theory of Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Abdo, Z.; Schneider, G.M.; Koenig, S.S.K.; McCulle, S.L.; Karlebach, S.; Gorle, R.; Russell, J.; Tacket, C.O.; et al. Vaginal Microbiome of Reproductive-Age Women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4680–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fettweis, J.M.; Brooks, J.P.; Serrano, M.G.; Sheth, N.U.; Girerd, P.H.; Edwards, D.J.; Strauss, J.F.; The Vaginal Microbiome Consortium; Jefferson, K.K.; Buck, G.A. Differences in vaginal microbiome in African American women versus women of European ancestry. Microbiology 2014, 160, 2272–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Song, X.; Wei, W.; Zhong, H.; Dai, J.; Lan, Z.; Li, F.; Yu, X.; Feng, Q.; Wang, Z.; et al. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, D.N.; Fiedler, T.L.; Marrazzo, J.M. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1899–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Chen, T.; Li, R. The Female Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Bacterial Vaginosis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 631972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekmezovic, M.; Mogavero, S.; Naglik, J.R.; Hube, B. Host-pathogen interactions during female genital tract infections. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Forney, L.J.; Ravel, J. Vaginal microbiome: Rethinking health and disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 66, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethlefsen, L.; Huse, S.; Sogin, M.L.; Relman, D.A. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Abu-Ali, G.; Huttenhower, C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Forster, S.C.; Tsaliki, E.; Vervier, K.; Strang, A.; Simpson, N.; Kumar, N.; Stares, M.D.; Rodger, A.; Brocklehurst, P.; et al. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean section birth. Nature 2019, 574, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.E.; Tuddenham, S.; Shardell, M.D.; Klebanoff, M.A.; Ghanem, K.G.; Brotman, R.M. Bacterial vaginosis and spontaneous clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis in the longitudinal study of vaginal flora. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, L.R.; Achilles, S.L.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Burgener, A.; Crucitti, T.; Fredricks, D.N.; Jaspan, H.B.; Kaul, R.; Kaushic, C.; Klatt, N. The evolving facets of bacterial vaginosis: Implications for HIV transmission. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2019, 35, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudnadottir, U.; Debelius, J.W.; Du, J.; Hugerth, L.W.; Danielsson, H.; Schupe-Koistinen, I.; Fransson, E.; Brusselaers, N. The vaginal microbiome and the risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Noel-Romas, L.; Perner, M.; Knodel, S.; Molatlhegi, R.; Hoger, S.; Birse, K.; Zuend, C.F.; McKinnon, L.R.; Burgener, A.D. Non-Lactobacillus-dominant and polymicrobial vaginal microbiomes are more common in younger South African women and predictive of increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus acquisition. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, N.R.; Cheu, R.; Birse, K.; Zevin, A.S.; Perner, M.; Noël-Romas, L.; Grobler, A.; Westmacott, G.; Xie, I.Y.; Butler, J.; et al. Vaginal bacteria modify HIV tenofovir microbicide efficacy in African women. Science 2017, 356, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, R.B.; Kip, K.E.; Hillier, S.L.; Soper, D.E.; Stamm, C.A.; Sweet, R.L.; Rice, P.; Richter, H.E. A cluster analysis of bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 162, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitich, H.; Kiss, H. Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2007, 21, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svare, J.A.; Schmidt, H.; Hansen, B.B.; Lose, G. Bacterial vaginosis in a cohort of Danish pregnant women: Prevalence and relationship with preterm delivery, low birthweight and perinatal infections. BJOG 2006, 113, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaniewski, P.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. The microbiome and gynaecological cancer development, prevention and therapy. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020, 17, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, D.H.; Fazzari, M.; Minkoff, H.; Hillier, S.L.; Sha, B.; Glesby, M.; Levine, A.M.; Burk, R.; Palefsky, J.M.; Moxley, M.; et al. Effects of bacterial vaginosis and other genital infections on the natural history of human papillomavirus infection in HIV-1-infected and high-risk HIV-1-uninfected women. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventolini, G.; Vieira-Baptista, P.; De Seta, F.; Verstraelen, H.; Lonnee-Hoffmann, R.; Lev-Sagie, A. The Vaginal Microbiome: IV. The Role of Vaginal Microbiome in Reproduction and in Gynecologic Cancers. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2022, 26, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.; Tang, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Wang, T. Exploring vaginal microbiome: From traditional methods to metagenomic next-generation sequencing-a systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1578681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preksha, G.; Yesheswini, R.; Srikanth, C.V. Cell culture techniques in gastrointestinal research: Methods, possibilities and challenges. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2021, 64, S52–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Ray, P.; Angrup, A. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria: In routine and research. Anaerobe 2022, 75, 102559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignyś, I.; Szachta, P.; Gałecka, M.; Schmidt, M.; Pazgrat-Patan, M. Methods of analysis of gut microorganism–actual state of knowledge. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2014, 21, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolles, A.; Ruiz, L. Methods for isolation and recovery of bifidobacteria. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2278, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.C.; Dubourg, G.; Million, M.; Cadoret, F.; Bilen, M.; Fenollar, F.; Levasseur, A.; Rolain, J.M.; Fournier, P.E.; Raoult, D. Culturing the human microbiota and culturomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Morris, A.; Ghedin, E. The human mycobiome in health and disease. Genome Med. 2013, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Chopra, C.; Mehta, M.; Sharma, V.; Mallubhotla, S.; Sistla, S.; Sistla, J.C.; Bhushan, I. An Insight into Vaginal Microbiome Techniques. Life 2021, 11, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygaard, A.B.; Tunsj, H.S.; Meisal, R.; Charnock, C.J.S.R. A preliminary study on the potential of Nanopore MinION and Illumina MiSeq 16S rRNA gene sequencing to characterize building-dust microbiomes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motooka, D.; Fujimoto, K.; Tanaka, R.; Yaguchi, T.; Gotoh, K.; Maeda, Y.; Furuta, Y.; Kurakawa, T.; Goto, N.; Yasunaga, T. Fungal ITS1 deep-sequencing strategies to reconstruct the composition of a 26-species community and evaluation of the gut mycobiota of healthy Japanese individuals. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipitsyna, E.; Roos, A.; Datcu, R.; Hallén, A.; Fredlund, H.; Jensen, J.S.; Engstrand, L.; Unemo, M. Composition of the vaginal microbiota in women of reproductive age—Sensitive and specific molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is possible? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirichoat, A.; Sankuntaw, N.; Engchanil, C.; Buppasiri, P.; Faksri, K.; Namwat, W.; Chantratita, W.; Lulitanond, V. Comparison of different hypervariable regions of 16S rRNA for taxonomic profiling of vaginal microbiota using next-generation sequencing. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretsky, R.; Rodriguez, R.L.M.; Luo, C.; Tsementzi, D.; Konstantinidis, K.T. Strengths and limitations of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing in revealing temporal microbial community dynamics. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad Rizal, N.S.; Neoh, H.-m.; Ramli, R.; A/L K Periyasamy, P.R.; Hanafiah, A.; Abdul Samat, M.N.; Tan, T.L.; Wong, K.K.; Nathan, S.; Chieng, S.; et al. Advantages and Limitations of 16S rRNA Next-Generation Sequencing for Pathogen Identification in the Diagnostic Microbiology Laboratory: Perspectives from a Middle-Income Country. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, P.A.; Ramos, J.N.; Vasconcellos, L.; Costa, L.V.; Forsythe, S.J.; Brandão, M.L.L. Application and Limitations of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Identifying WHO Priority Pathogenic Gram-Negative Bacilli. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 6353–6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Blanco-Pintos, T.; Tomás, I. Critical review of 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow in microbiome studies: From primer selection to advanced data analysis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 38, 347–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaban, B.; Links, M.G.; Jayaprakash, T.P.; Wagner, E.C.; Bourque, D.K.; Lohn, Z.; Albert, A.Y.; van Schalkwyk, J.; Reid, G.; Hemmingsen, S.M. Characterization of the vaginal microbiota of healthy Canadian women through the menstrual cycle. Microbiome 2014, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.B.; Liao, Q.P. Analysis of diversity of vaginal microbiota in healthy Chinese women by using DNA-fingerprinting. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2012, 44, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, C.; Romero-González, R.; Albani-Campanario, M.; Figueroa-Damián, R.; Meraz-Cruz, N.; Hernández-Guerrero, C. Vaginal microbiota of healthy pregnant Mexican women is constituted by four lactobacillus species and several vaginosis-associated bacteria. Infect. Dis. Obs. Gynecol. 2011, 2011, 851485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aagaard, K.; Riehle, K.; Ma, J.; Segata, N.; Mistretta, T.A.; Coarfa, C.; Raza, S.; Rosenbaum, S.; Van den Veyver, I.; Milosavljevic, A.; et al. A metagenomic approach to characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, I.M.; Summers, P.R.; Larsen, B.; Giraldo, P.C.; Witkin, S.S. Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and lactobacilli. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 120.e1–120.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, J.R.; Ravel, J. The vocabulary of microbiome research: A proposal. Microbiome 2015, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, K.; Petrosino, J.; Keitel, W.; Watson, M.; Katancik, J.; García, N.; Patel, S.; Cutting, M.; Madden, T.; Hamilton, H.; et al. The Human Microbiome Project strategy for comprehensive sampling of the human microbiome and why it matters. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.S.; Li, L. Quantifying the Human Vaginal Community State Types (CSTs) with the Species Specificity Index. Peer J. 2017, 5, e3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, B.; Cruciani, F.; Picone, G.; Parolin, C.; Donders, G.; Laghi, L. Vaginal Microbiome and Metabolome Highlight Specific Signatures of Bacterial Vaginosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajer, P.; Brotman, R.M.; Bai, G.; Sakamoto, J.; Schütte, U.M.; Zhong, X.; Koening, S.S.; Fu, L.; Ma, Z.S.; Zhou, X.; et al. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 132ra52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, M.T.; Ma, B.; Gajer, P.; Brown, S.; Humphrys, M.S.; Holm, J.B.; Waetjen, L.E.; Brotman, R.M.; Ravel, J. VALENCIA: A Nearest Centroid Classification Method for Vaginal Microbial Communities Based on Composition. Microbiome 2020, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirota, I.; Zarek, S.M.; Segars, J.H. Potential influence of the microbiome on infertility and assisted reproductive technology. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2014, 32, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Wijgert, J.H.; Borgdorff, H.; Verhelst, R.; Crucitti, T.; Verstraelen, H.; Jespers, V. The vaginal microbiota: What have we learned after a decade of molecular characterization? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Soares, H.; Suzuki, H.; Hickey, R.J.; Forney, L.J. Comparative functional genomics of Lactobacillus spp. Reveals possible mechanisms for specialization of vaginal lactobacilli to their environment. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 1458–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroutcheva, A.; Gariti, D.; Simon, M.; Shott, S.; Faro, J.; Simoes, J.A.; Gurguis, A.; Faro, S. Defense factors of vaginal lactobacilli. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, S.S.; Mendes-Soares, H.; Linhares, I.M.; Jayaram, A.; Ledger, W.J.; Forney, L.J. Influence of vaginal bacteria and D- and L-lactic acid isomers on vaginal extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer: Implications for protection against upper genital tract infections. mBio 2013, 4, e00460-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, S.S.; Linhares, I.M. Why do lactobacilli dominate the human vaginal microbiota? BJOG 2017, 124, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskey, E.R.; Cone, R.A.; Whaley, K.J.; Moench, T.R. Origins of vaginal acidity: High D/L lactate ratio is consistent with bacteria being the primary source. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 1809–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasioudis, D.; Beghini, J.; Bongiovanni, A.M.; Giraldo, P.C.; Linhares, I.M.; Witkin, S.S. α-Amylase in vaginal fluid: Association with conditions favorable to dominance of Lactobacillus. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, V.L.; Smith, S.B.; McComb, E.J.; Tamarelle, J.; Ma, B.; Humphrys, M.S.; Gajer, P.; Gwilliam, K.; Schaefer, A.M.; Lai, S.K.; et al. The cervicovaginal microbiota-host interaction modulates Chlamydia trachomatis infection. mBio 2019, 10, e01548-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachedjian, G.; Aldunate, M.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Cone, R.A. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res. Microbiol. 2017, 168, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, E.L.; Vodstrcil, L.A.; Bradshaw, C.S. Unravelling the vaginal microbiome, impact on health and disease. Curr. Opin. Obs. Gynecol. 2024, 36, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbergh, P.A. Lactic acid bacteria, their metabolic products and interference with microbial growth. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 12, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, S.; Barbes, C. Role played by lactobacilli in controlling the population of vaginal pathogens. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, V.; Maldonado, A.; Fernandez, L.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Connor, R.I. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by lactic acid bacteria from human breastmilk. Breastfeed. Med. 2010, 5, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldunate, M.; Tyssen, D.; Johnson, A.; Zakir, T.; Sonza, S.; Moench, T.; Cone, R.; Tachedjian, G. Vaginal concentrations of lactic acid potently inactivate HIV. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Diaz, D.J.; Tyssen, D.; Hayward, J.A.; Gugasyan, R.; Hearps, A.C.; Tachedjian, G. Distinct immune responses elicited from cervicovaginal epithelial cells by lactic acid and short chain fatty acids associated with optimal and nonoptimal vaginal microbiota. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwecht, I.; Nazli, A.; Gill, B.; Kaushic, C. Lactic acid enhances vaginal epithelial barrier integrity and ameliorates inflammatory effects of dysbiotic short chain fatty acids and HIV-1. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhanzva, M.T.; Abrahams, A.G.; Gamieldien, H.; Froissart, R.; Jaspan, H.; Jaumdally, S.Z.; Barnabas, S.L.; Dabee, S.; Bekker, L.G.; Gray, G.; et al. Inflammatory and antimicrobial properties differ between vaginal Lactobacillus isolates from South African women with nonoptimal versus optimal microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, G.; Doherty, E.; To, T.; Sutherland, A.; Grant, J.; Junaid, A.; Gulati, A.; LoGRande, N.; Izadifar, Z.; Timilsina, S.S.; et al. Vaginal microbiome-host interactions modeled in a human vagina-on-a-chip. Microbiome 2022, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.I.; Lievens, E.; Malik, S.; Imholz, N.; Lebeer, S. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyancheva, G.; Marzotto, M.; Dellaglio, F.; Torriani, S. Bacteriocin production and gene sequencing analysis from vaginal Lactobacillus strains. Arch. Microbiol. 2014, 196, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, S.; Abla, H.; Colmer-Hamood, J.A.; Ventolini, G.; Hamood, A.N. Under conditions closely mimicking vaginal fluid, Lactobacillus jensenii strain 62B produces a bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance that targets and eliminates Gardnerella species. Microbiology 2023, 169, 001409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torcia, M.G. Interplay among Vaginal Microbiome, Immune Response and Sexually Transmitted Viral Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Dong, B.; Xue, H.; Lei, H.; Lu, Y.; Wei, X.; Sun, P. Changes of the vaginal microbiota in HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A cross-sectional analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atassi, F.; Servin, A.L. Individual and co-operative roles of lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide in the killing activity of enteric strain Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC933 and vaginal strain Lactobacillus gasseri KS120.1 against enteric, uropathogenic and vaginosis-associated pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 304, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgibnev, A.V.; Kremleva, E.A. Vaginal protection by H2O2-producing lactobacilli. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2015, 8, e22913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanlon, D.E.; Lanier, B.R.; Moench, T.R.; Cone, R.A. Cervicovaginal fluid and semen block the microbicidal activity of hydrogen peroxide produced by vaginal lactobacilli. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanlon, D.E.; Moench, T.R.; Cone, R.A. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanlon, D.E.; Moench, T.R.; Cone, R.A. Vaginal pH and Microbicidal Lactic Acid When Lactobacilli Dominate the Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norenhag, J.; Edfeldt, G.; Stalberg, K.; Garcia, F.; Hugerth, L.W.; Engstrand, L.; Fransson, E.; Du, J.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; Olovsson, M. Compositional and Functional Differences of the Vaginal Microbiota of Women with and without Cervical Dysplasia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Han, D.; Meng, J.; Wang, H.; Cao, G. L-lysine ameliorates sepsis-induced acute lung injury in a lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Tan, P.; Ma, N.; Ma, X. Physiological Functions of Threonine in Animals: Beyond Nutrition Metabolism. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaifem, J.; Gonçalves, L.G.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Cunha, C.; Carvalho, A.; Torrado, E. L-Threonine Supplementation During Colitis Onset Delays Disease Recovery. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Vowinckel, J.; Keller, M.A.; Ralser, M. Methionine Metabolism Alters Oxidative Stress Resistance via the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2016, 24, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, M.K.; Rao, M.N. Antiinflammatory activity of methionine, methionine sulfoxide and methionine sulfone. Agents Actions 1990, 31, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navik, U.; Sheth, V.G.; Sharma, N.; Tikoo, K. L-Methionine supplementation attenuates high-fat fructose diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by modulating lipid metabolism, fibrosis, and inflammation in rats. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 4941–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymonowicz, K.A.; Chen, J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biol. Med. 2020, 17, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, N.; Bosch, F.X.; De Sanjosé, S.; Herrero, R.; Castellsagué, X.; Shah, K.V.; Snijders, P.J.; Meijer, C.J.; International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, G.M.; Rana, R.K.; Franceschi, S.; Smith, J.S.; Gough, G.; Pimenta, J.M. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in low-grade cervical lesions: Comparison by geographic region and with cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.R.; de Melo, C.M.L.; Barros, M.L.C.M.G.R.; de Cássia Pereira de Lima, R.; de Freitas, A.C.; Venuti, A. Activities of Stromal and Immune Cells in HPV-Related Cancers. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L.J.P.; McKinnon, L.R.; Yende-Zuma, N.; Garrett, N.; Baxter, C.; Kharsany, A.B.M.; Archary, D.; Rositch, A.; Samsunder, N.; Mansoor, L.E.; et al. HPV Infection and the Genital Cytokine Milieu in Women at High Risk of HIV Acquisition. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Tan, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, N.; Tian, J.; Qu, P. The Value of Cytokine Levels in Triage and Risk Prediction for Women with Persistent High-Risk Human Papilloma Virus Infection of the Cervix. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2019, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, L.; Mtshali, A.; Mzobe, G.; Liebenberg, L.J.; Ngcapu, S. Role of Immunity and Vaginal Microbiome in Clearance and Persistence of Human Papillomavirus Infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 927131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, S.E.; Kiviat, N.B. Are Genital Infections and Inflammation Cofactors in the Pathogenesis of Invasive Cervical Cancer? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 1592–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, K.J.; Dalgleish, A.G. Chronic Immune Activation and Inflammation as the Cause of Malignancy. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Liu, Z.; Sun, T.; Zhu, L. Cervicovaginal Microbiome, High-Risk HPV Infection and Cervical Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 287, 127857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąszczak, K.; Barczyński, B.; Kondracka, A. Does Lactobacillus Exert a Protective Effect on the Development of Cervical and Endometrial Cancer in Women? Cancers 2022, 14, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; MacIntyre, D.A.; Marchesi, J.R.; Lee, Y.S.; Bennett, P.R.; Kyrgiou, M. The Vaginal Microbiota, Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: What Do We Know and Where Are We Going Next? Microbiome 2016, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, C.; Li, F.; Zhao, J.; Wan, X.; Wang, K. Cervicovaginal microbiota composition correlates with the acquisition of high-risk human papillomavirus types. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokiyaraj, S.; Seo, S.S.; Kwon, M.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, M.K. Association of cervical microbial community with persistence, clearance and negativity of Human Papillomavirus in Korean women: A longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, K.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Fiedler, T.L.; Anzala, O.; Kimani, J.; Mochache, V.; Wallis, J.M.; Fredricks, D.N.; McClelland, R.S.; Balkus, J.E. Vaginal Bacteria and Risk of Incident and Persistent Infection with High-Risk Subtypes of Human Papillomavirus: A Cohort Study Among Kenyan Women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, M.A.; Leenders, W.P.J.; Huynen, M.A.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Andralojc, K.M. Temporal composition of the cervicovaginal microbiome associates with hrHPV infection outcomes in a longitudinal study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wang, W.; Li, D.; Wu, A.; Hong, Z.; Di, W.; Qiu, L. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia progression are associated with increased vaginal microbiome diversity in a Chinese cohort. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.A.; Yang, E.J.; Kim, N.R.; Hong, S.R.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, C.S.; Shim, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.J. Changes of Vaginal Microbiota during Cervical Carcinogenesis in Women with Human Papillomavirus Infection. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasniewski, W.; Wolun-Cholewa, M.; Kotarski, J.; Warchol, W.; Kuzma, D.; Kwasniewska, A.; Gozdzicka-Jozefiak, A. Microbiota dysbiosis is associated with HPV-induced cervical carcinogenesis. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 7035–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, L.; Han, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, C. Vaginal Microbiome Dysbiosis Is Associated with the Different Cervical Disease Status. J. Microbiol. 2023, 61, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teka, B.; Yoshida-Court, K.; Firdawoke, E.; Chanyalew, Z.; Gizaw, M.; Addissie, A.; Mihret, A.; Colbert, L.E.; Napravnik, T.C.; El Alam, M.B.; et al. Cervicovaginal Microbiota Profiles in Precancerous Lesions and Cervical Cancer among Ethiopian Women. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.; Li, C.; Ying, C. Characterization of Vaginal Microbiota in Chinese Women with Cervical Squamous Intra-Epithelial Neoplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Su, M.; Diao, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhan, Y. Characteristics of Vaginal Microbiota in Various Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, H.; Li, D.; Wang, M.; Li, Y. Association of Cervical Dysbacteriosis, HPV Oncogene Expression, and Cervical Lesion Progression. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0015122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, N.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Song, L.; Lyu, Y.; et al. Cervicovaginal Microbiota Disorder Combined with the Change of Cytosine Phosphate Guanine Motif- Toll like Receptor 9 Axis Was Associated with Cervical Cancerization. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 17371–17381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrgiou, M.; Moscicki, A.B. Vaginal Microbiome and Cervical Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, S.; Ishii, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Kukimoto, I. Nuclear proinflammatory cytokine S100A9 enhances expression of human papillomavirus oncogenes via transcription factor TEAD1. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0081523, Correction in J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0149923. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00815-23.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jia, L.; Yu, Y.; Jin, L. Lactic acid induced microRNA-744 enhances motility of SiHa cervical cancer cells through targeting ARHGAP5. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 298, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaniewski, P.; Barnes, D.; Goulder, A.; Cui, H.; Roe, D.J.; Chase, D.M.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Linking Cervicovaginal Immune Signatures, HPV and Microbiota Composition in Cervical Carcinogenesis in non-Hispanic and Hispanic Women. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; MacIntyre, D.A.; Lee, Y.S.; Smith, A.; Marchesi, J.R.; Lehne, B.; Bhatia, R.; Lyons, D.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Li, J.V.; et al. Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Disease Progression is Associated with Increased Vaginal Microbiome Diversity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotman, R.M.; Shardell, M.D.; Gajer, P.; Tracy, J.K.; Zenilman, J.M.; Ravel, J.; Gravitt, P.E. Interplay Between the Temporal Dynamics of the Vaginal Microbiota and Human Papillomavirus Detection. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Weng, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X. Comparison of the Vaginal Microbiota Diversity of Women with and Without Human Papillomavirus Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.H.; Kuo, M.L.; Chen, C.A.; Chou, C.H.; Cheng, W.F.; Chang, M.C.; Su, J.L.; Hsieh, C.Y. The anti-apoptotic role of interleukin-6 in human cervical cancer is mediated by up-regulation of Mcl-1 through a PI 3-K/Akt pathway. Oncogene 2001, 20, 5799–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahne-Zeppenfeld, J.; Schröer, N.; Walch-Rückheim, B.; Oldak, M.; Gorter, A.; Hegde, S.; Smola, S. Cervical cancer cell-derived interleukin-6 impairs CCR7-dependent migration of MMP-9-expressing dendritic cells. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Li, F.; Shao, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Luan, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liang, L.; et al. IL-8 is upregulated in cervical cancer tissues and is associated with the proliferation and migration of HeLa cervical cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarsingh, J.D.; Łaniewski, P.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Immunometabolic and potential tumor-promoting changes in 3D cervical cell models infected with bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golijow, C.D.; Abba, M.C.; Mouron, S.A.; Laguens, R.M.; Dulout, F.N.; Smith, J.S. Chlamydia trachomatis and Human papillomavirus infections in cervical disease in Argentine women. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 96, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łaniewski, P.; Joe, T.R.; Jimenez, N.R.; Eddie, T.L.; Bordeaux, S.J.; Quiroz, V.; Peace, D.J.; Cui, H.; Roe, D.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; et al. Viewing Native American Cervical Cancer Disparities through the Lens of the Vaginal Microbiome: A Pilot Study. Cancer Prev. Res. 2024, 17, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Lu, W. The Alterations of Vaginal Microbiome in HPV16 Infection as Identified by Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Bryant, A.; Dickinson, H.O. Surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, Cd001318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Lu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Liu, H.; Xu, C. Cervical microbiome is altered in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia after loop electrosurgical excision procedure in china. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, E.; D’Accolti, M.; Santi, E.; Soffritti, I.; Conzadori, S.; Mazzacane, S.; Greco, P.; Contini, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. Vaginal Microbiota and Cytokine Microenvironment in HPV Clearance/Persistence in Women Surgically Treated for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: An Observational Prospective Study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 540900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DI Pierro, F.; Criscuolo, A.A.; Dei Giudici, A.; Senatori, R.; Sesti, F.; Ciotti, M.; Piccione, E. Oral administration of Lactobacillus crispatus M247 to papillomavirus-infected women: Results of a preliminary, uncontrolled, open trial. Minerva Obs. Gynecol. 2021, 73, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellino, M.; Cascardi, E.; Laganà, A.S.; Di Vagno, G.; Malvasi, A.; Zaccaro, R.; Maggipinto, K.; Cazzato, G.; Scacco, S.; Tinelli, R.; et al. Lactobacillus crispatus M247 oral administration: Is it really an effective strategy in the management of papilloma virus infected women? Infect. Agents Cancer 2022, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, V.; Renard, N.; Makar, A.; Van Royen, P.; Bogers, J.P.; Lardon, F.; Peeters, M.; Baay, M. Probiotics enhance the clearance of human papillomavirus-related cervical lesions: A prospective controlled pilot study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 22, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.C.; Fu, H.C.; Tseng, C.W.; Wu, C.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Lin, H. The influence of probiotics on genital high-risk human papilloma virus clearance and quality of cervical smear: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, F.; Chen, J.; Luo, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, T. Effectiveness of vaginal probiotics Lactobacillus crispatus chen-01 in women with high-risk HPV infection: A prospective controlled pilot study. Aging 2024, 16, 11446–11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, E.; Cazzato, G.; Daniele, A.; Silvestris, E.; Cormio, G.; Di Vagno, G.; Malvasi, A.; Loizzi, V.; Scacco, S.; Pinto, V.; et al. Association between Cervical Microbiota and HPV: Could This Be the Key to Complete Cervical Cancer Eradication? Biology 2022, 11, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagenaur, L.A.; Hemmerling, A.; Chiu, C.; Miller, S.; Lee, P.P.; Cohen, C.R.; Parks, T.P. Connecting the Dots: Translating the Vaginal Microbiome Into a Drug. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, S296–S306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, E.; Recine, N.; Domenici, L.; Giorgini, M.; Pierangeli, A.; Panici, P.B. Long-term Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54 application to restore a balanced vaginal ecosystem: A promising solution against HPV-infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Kong, J.; Chai, Z.; Tao, G.X.; Cai, X.; Ying, L.; Shi, J. Recombinant interferon α-2B gel combined with Lactobacillus as a vaginal capsule in patients with cervical high-risk human papillomavirus. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2022, 21, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, A.; Reyes-Lagos, J.J.; Peña-Castillo, M.A.; Nirmalkar, K.; García-Mena, J.; Pacheco-López, G. Vaginal Microbiota Is Stable and Mainly Dominated by Lactobacillus at Third Trimester of Pregnancy and Active Childbirth: A Longitudinal Study of Ten Mexican Women. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Peña, M.D.; Castro-Escarpulli, G.; Aguilera-Arreola, M.G. Lactobacillus species isolated from vaginal secretions of healthy and bacterial vaginosis-intermediate Mexican women: A prospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audirac-Chalifour, A.; Torres-Poveda, K.; Bahena-Román, M.; Téllez-Sosa, J.; Martínez-Barnetche, J.; Cortina-Ceballos, B.; López-Estrada, G.; Delgado-Romero, K.; Burguete-García, A.I.; Cantú, D.; et al. Cervical Microbiome and Cytokine Profile at Various Stages of Cervical Cancer: A Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares-Leal, G.L.; Coronel-Martínez, J.A.; Rodríguez-Morales, M.; Rangel-Cuevas, I.; Bustamante-Montes, L.P.; Sandoval-Trujillo, H.; Ramírez-Durán, N. Preliminary Identification of the Aerobic Cervicovaginal Microbiota in Mexican Women with Cervical Cancer as the First Step Towards Metagenomic Studies. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 838491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulato-Briones, I.B.; Rodriguez-Ildefonso, I.O.; Jiménez-Tenorio, J.A.; Cauich-Sánchez, P.I.; Méndez-Tovar, M.d.S.; Aparicio-Ozores, G.; Bautista-Hernández, M.Y.; González-Parra, J.F.; Cruz-Hernández, J.; López-Romero, R.; et al. Cultivable Microbiome Approach Applied to Cervical Cancer Exploration. Cancers 2024, 16, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Ramírez, M.E.; Partida-Rodríguez, O.; Moran, P.; Serrano-Vázquez, A.; Pérez-Juárez, H.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.E.; Arrieta, M.C.; Ximénez- García, C.; Finlay, B.B. Cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions are associated with differences in the vaginal microbiota of Mexican women. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00143-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ortíz, I.A.; Puente-Rivera, J.; Ordaz-Pérez, G.; Bonilla-Cortés, A.Y.; Figueroa-Arredondo, P.; Serrano-Bello, C.A.; García-Moncada, E.; Acosta-Altamirano, G.; Artigas-Pérez, D.E.; Bravata-Alcántara, J.C.; et al. Brachybacterium conglomeratum Is Associated with Cervicovaginal Infections and Human Papilloma Virus in Cervical Disease of Mexican Female Patients. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Garcia, E.K.; Contreras-Paredes, A.; Martinez-Abundis, E.; Garcia-Chan, D.; Lizano, M.; de la Cruz-Hernandez, E. Molecular epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis and its association with genital micro-organisms in asymptomatic women. J. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Morelos, P.; Bandala, C.; Jímenez-Tenorio, J.; Valdespino-Zavala, M.; Rodríguez-Esquivel, M.; Gama-Ríos, R.A.; Bandera, A.; Mendoza-Rodríguez, M.; Taniguchi, K.; Marrero-Rodríguez, D.; et al. Bacterias relacionadas con vaginosis bacteriana y su asociación a la infección por virus del papiloma humano. Med. Clín. 2017, 152, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Community State Types (CST) * | Dominant Species | Associated Health Status | Associated Pathologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| CST-I | Lactobacillus crispatus | Highly healthy and stable | Lower risk of infections (HPV) and preterm birth |

| CST-II | Lactobacillus gasseri | Healthy and stable | Lower risk of sexually transmitted infections (STI) and preterm birth |

| CST-III | Lactobacillus iners | Healthy, less stable | Greater tendency to dysbiosis; coexists with pathogens |

| CST-V | Lactobacillus jensenii | Healthy | Absence of pathologies |

| CST-IV | Lower abundance of Lactobacillus; high proportion of anaerobic bacteria | Dysbiosis | Bacterial vaginosis, STIs, candidiasis, viral infections (HPV, HIV) |

| CST-IV | CST-IV A Anaerococcus, Peptoniphilus, Corynebacterium, Prevotela, Finegoldia, Streptococcus CST-IV B Atopobium, Gardnerella, Sneathia, Mobiluncus, Megasphaera, Clostridiales CST-IV C Varies by subgroup Divided into five subgroups | Dysbiosis | Bacterial vaginosis |

| CST-IV C0 Prevotella CST-IV C1 Streptococcus CST-IV C2 Enterococcus CST-IV C3 Bifidobacterium CST-IV C4 Staphylococcus | Dysbiosis | Bacterial vaginosis |

| Author Region | Identified Strain * Healthy | Identified Strain * Disease | Sample Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hernández-Rodríguez et al. [43] Mexico City | L. acidophilus (predominant) L. iners, L gasseri L. delbrueckii | Bacterial vaginosis: Ureaplasma urealyticum | Samples collected during pregnancy |

| BVAB1 (Bacterial vaginosis associated bacteria | |||

| González-Sánchez et al. [139] Mexico City (Metropolitan area) | Lactobacillus (predominant) Gardnerella, Prevotella Atopobiaceae | No data | Samples collected at the third trimester of pregnancy |

| Martínez-Peña et al. [140] Mexico City | L. gasseri, L. fermentum, L. rhamnosus, L. jensenii, L. crispatus (low frequency) L. brevi | No data | Samples from healthy non-pregnant women |

| Audirac-Chalifour et al. [141] Mexico City and State of Morelos | L. crispatus L. iners | Sneathia spp. (predominant in SIL) Fusobacterium (in cervical cancer) | SIL and women with normal colposcopy (State of Morelos) |

| Cervical carcinoma (Mexico City) | |||

| Manzanares-Leal et al. [142] Mexico City | Staphilococcus pasteuri, Staphilococcus auricularis, Staphilococcus capitis subsp. capitis, Facklamia hominis, Paenibacillus orinalis, Pseudocitrobacter faecalis, Brevibacterium masiliense, Klebsiella oxytoca | Cervical cancer: Streptococcus urinalis, Escherichia coli, Bacillus safensis, Bacillus maliki, Corynebacterium jeikeium, Corynebacterium striatum, L. rhamnosus | Identified aerobic microbiome in women with and without cervical cancer |

| Mulato-Briones et al. [143] Mexico City | (i) Lacobacillus only, (ii) Lactobacillus plus Staphylo coccus (iii) Staphylococcus plus Streptococcus (iv) A group dominated primarily by Proteobacteria Most representative: L. jensenii, L. crispatus | Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Paenibacillus, Gemella Proteobacteria: E. coli, Acinetobacter, Campylobacter, Citrobacter Early-stage cancer: Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, with an absence of strict anaerobes | 50 non-cancer women 49 women with cervical cancer |

| Nieves-Ramírez et al. [144] Mexico City | No data | Brevibacterium aureum, Brachybacterium conglomeratum Associated with HPV16 infection and/or SIL | Samples from LSIL and HSIL |

| Cortés-Ortiz et al. [145] State of Mexico | No data | Brachybacterium conglomeratum (cervicovaginal lesion, LSIL, precancerous lesion) Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, Ureaplasma parvum | Cervicovaginal lesions, LSIL, precancerous lesions |

| Sánchez-García et al. [146] Tabasco | No data | Bacterial vaginosis: Increased prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma hominis | Women recruited during their routine gynecological inspection |

| Romero-Morales et al. [147] Guerrero | Gardnerella vaginalis Atopobium vaginae | Gardnerella vaginalis Atopobium vaginae | Samples without colposcopy and cytological alterations Precancerous lesions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lagunas-Cruz, M.d.C.; Valle-Mendiola, A.; Soto-Cruz, I. The Vaginal Microbiome and Host Health: Implications for Cervical Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020640

Lagunas-Cruz MdC, Valle-Mendiola A, Soto-Cruz I. The Vaginal Microbiome and Host Health: Implications for Cervical Cancer Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020640

Chicago/Turabian StyleLagunas-Cruz, María del Carmen, Arturo Valle-Mendiola, and Isabel Soto-Cruz. 2026. "The Vaginal Microbiome and Host Health: Implications for Cervical Cancer Progression" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020640

APA StyleLagunas-Cruz, M. d. C., Valle-Mendiola, A., & Soto-Cruz, I. (2026). The Vaginal Microbiome and Host Health: Implications for Cervical Cancer Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020640