Influence of Aza-Substitution on Molecular Structure, Spectral and Electronic Properties of t-Butylphenyl Substituted Vanadyl Complexes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

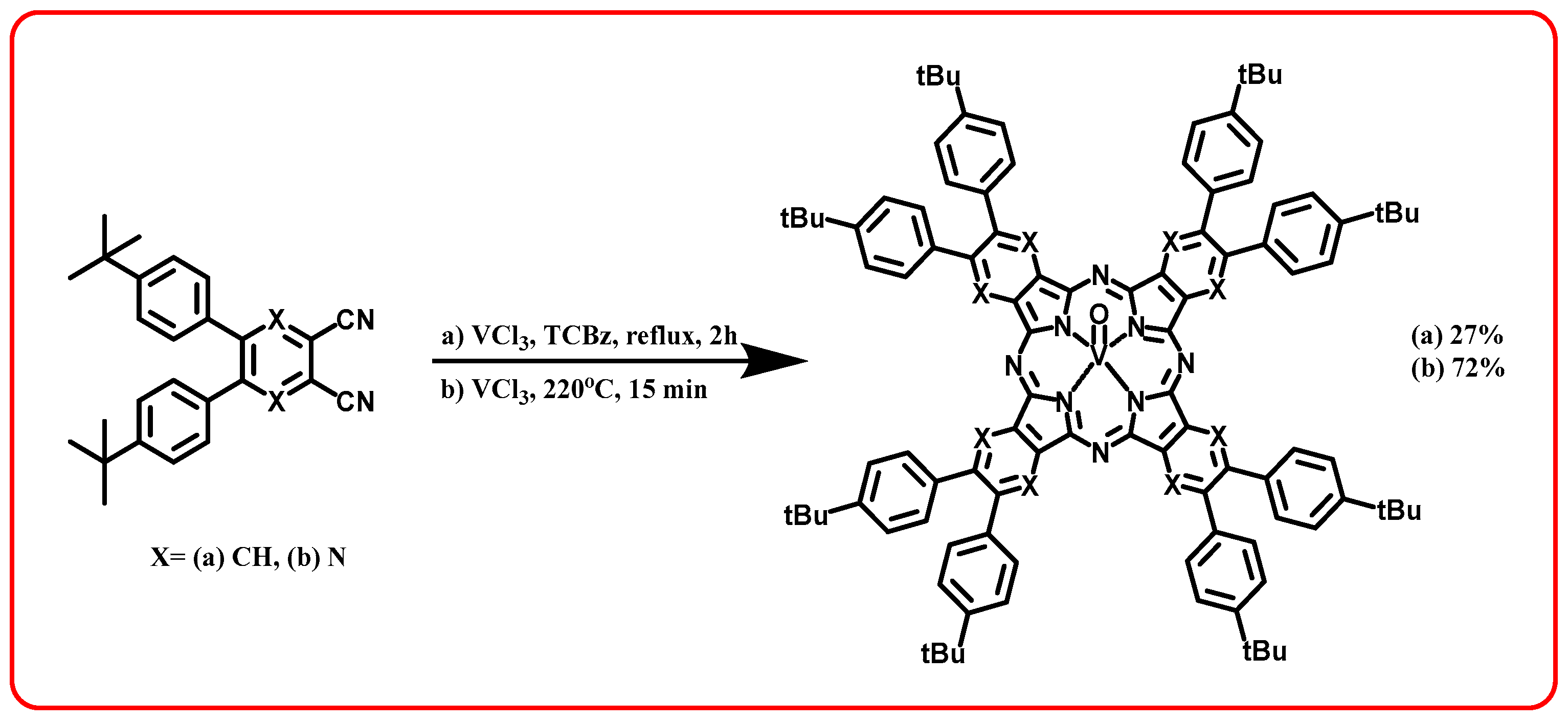

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Basic Properties

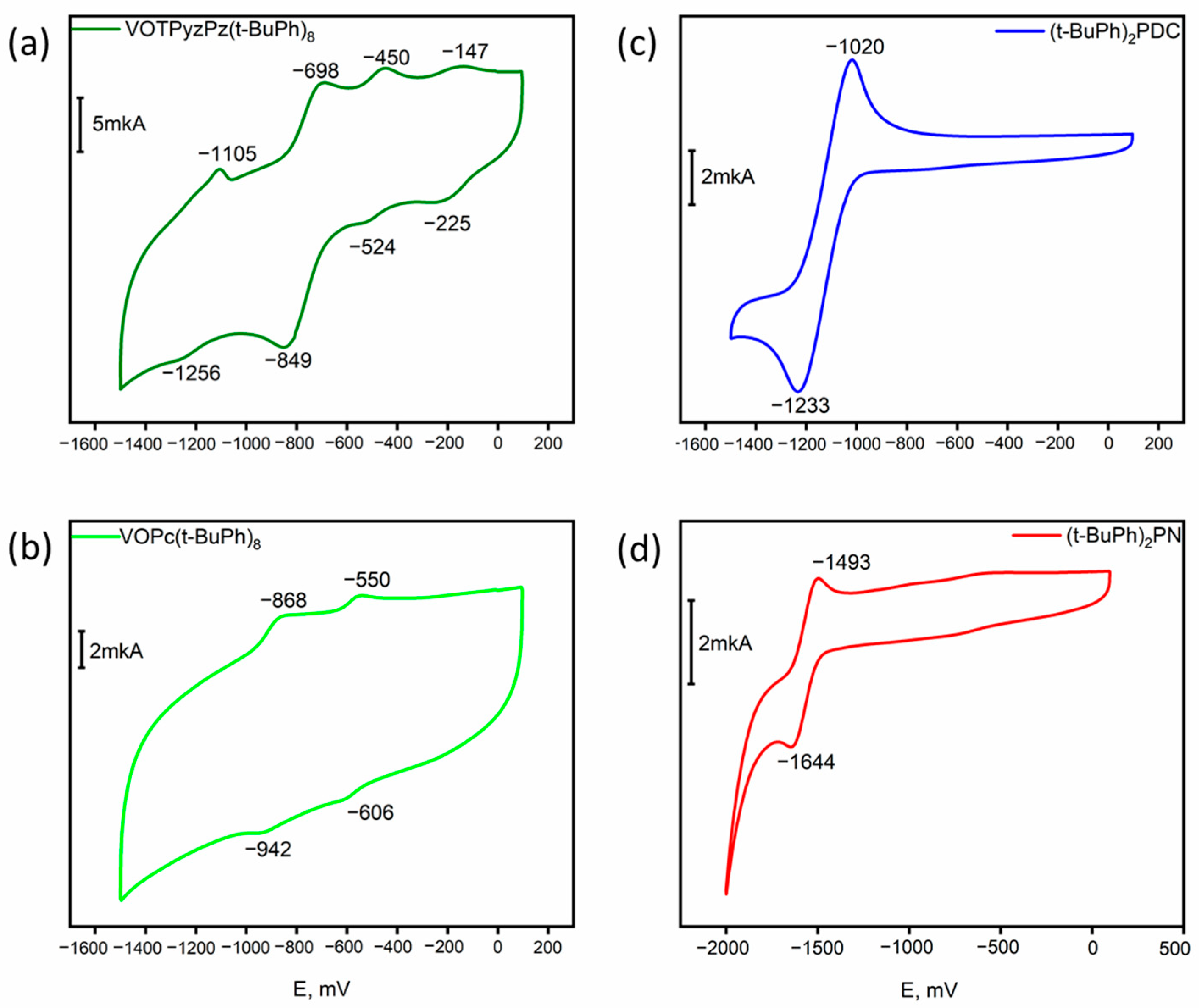

2.3. Electrochemistry

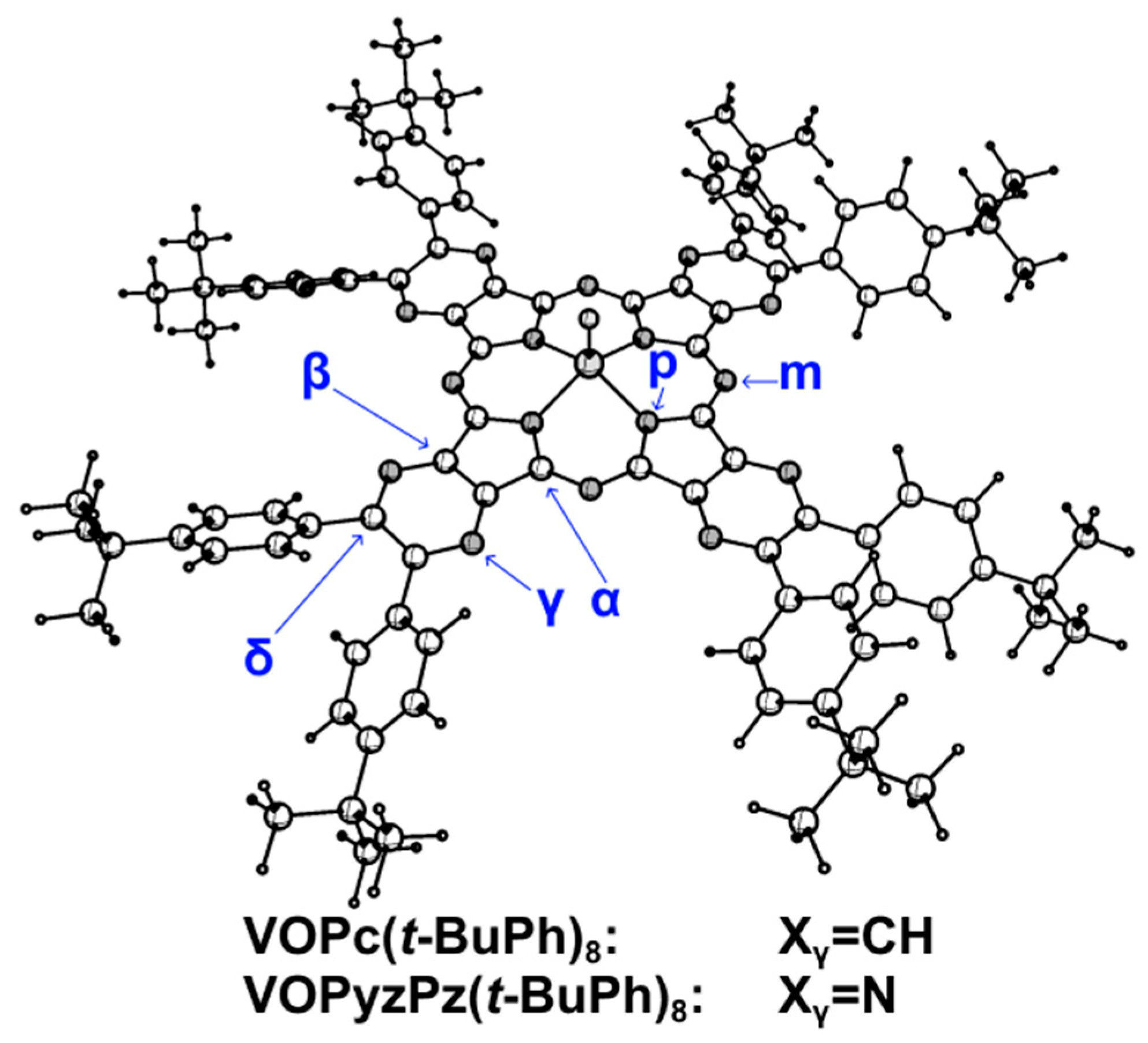

2.4. Molecular Structure

| VOPc | VOPc(t-BuPh)8 | VOTPyzPz | VOTPyzPz(t-BuPh)8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | C4v | C4 | C4v | C4 |

| V-O | 1.562 | 1.562 | 1.558 | 1.560 |

| h b | 0.586 | 0.587 | 0.572 | 0.575 |

| V-Np | 2.038 | 2.038 | 2.045 | 2.044 |

| Np-Cα | 1.367 | 1.368 | 1.368 | 1.370 |

| Nm-Cα | 1.315 | 1.315 | 1.310 | 1.311 |

| Cα-Cβ | 1.448 | 1.447 | 1.453 | 1.452 |

| Cβ-Cβ | 1.398 | 1.396 | 1.396 | 1.391 |

| Cβ-Xγ | 1.387 | 1.384 | 1.327 | 1.323 |

| Xγ-Cδ | 1.384 | 1.391 | 1.323 | 1.328 |

| Cδ-Cδ | 1.401 | 1.422 | 1.407 | 1.436 |

| Cδ-CPh | - | 1.478 | - | 1.474 |

| φ1 ≈ φ2 | - | 50.0 | - | 39.9 |

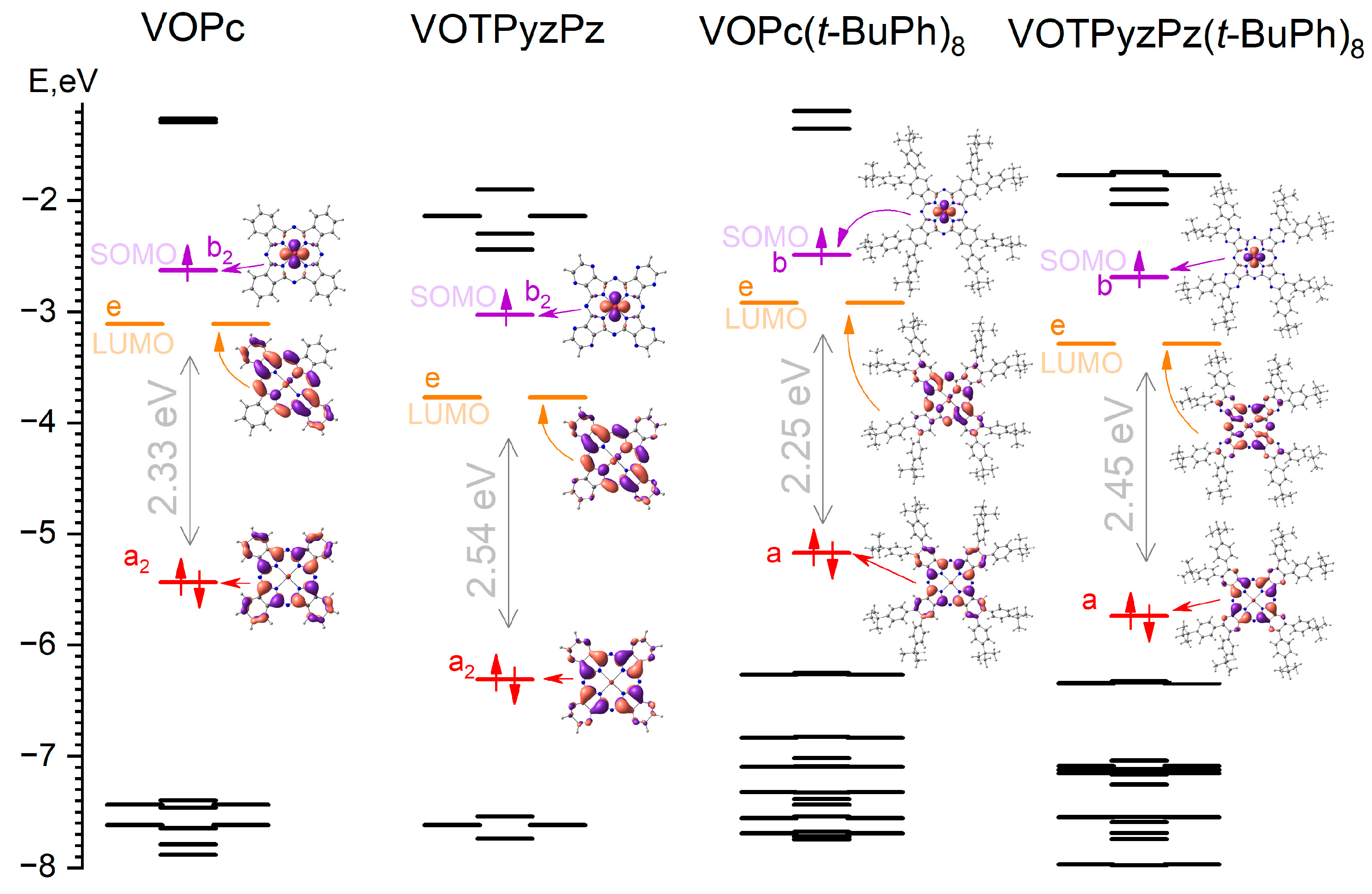

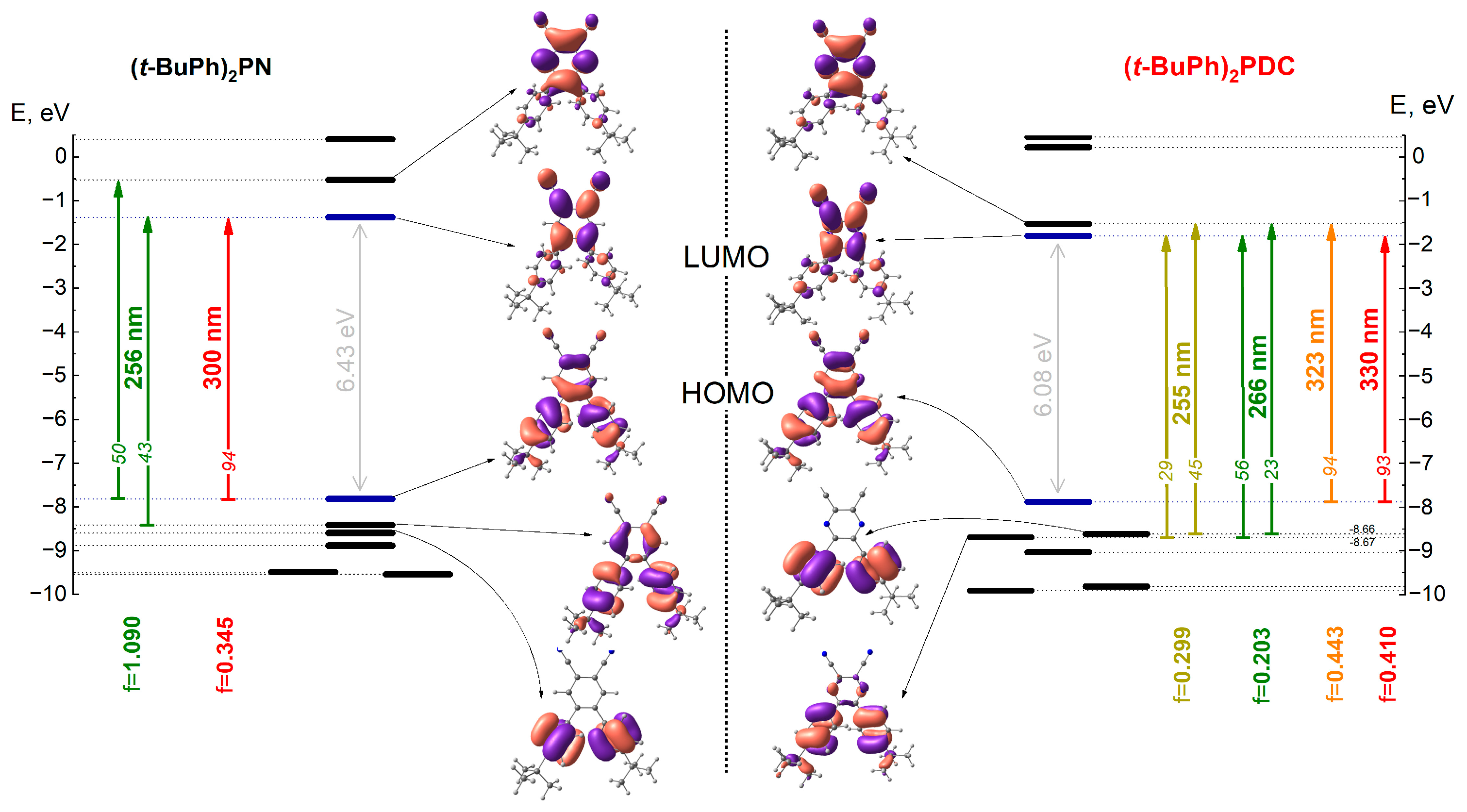

2.5. Electronic Structure

2.6. IR Spectra

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Spectral Study

3.3. Electrochemical Study

3.4. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ito, O.; D’Souza, F. Recent Advances in Photoinduced Electron Transfer Processes of Fullerene-Based Molecular Assemblies and Nanocomposites. Molecules 2012, 17, 5816–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wöhrle, D.; Schnurpfeil, G.; Makarov, S.G.; Kazarin, A.; Suvorova, O.N. Practical Applications of Phthalocyanines—from Dyes and Pigments to Materials for Optical, Electronic and Photo-electronic Devices. Macroheterocycles 2012, 5, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.G.; Rudine, A.B.; Wamser, C.C. Porphyrins and phthalocyanines in solar photovoltaic cells. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2010, 14, 759–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A.B. Phthalocyanine Metal Complexes in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 8152–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadish, K.M.; Smith, K.M.; Guilard, R. Handbook of Porphyrin Science; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliya, O.L.; Lukyanets, E.A.; Vorozhtsov, G.N. Catalysis and photocatalysis by phthalocyanines for technology, ecology and medicine. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 1999, 3, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakova, V.; Donzello, M.P.; Ercolani, C.; Zimcik, P.; Stuzhin, P.A. Tetrapyrazinoporphyrazines and their metal derivatives. Part II: Electronic structure, electrochemical, spectral, photophysical and other application related properties. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 361, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, A.G.; Gorbunova, Y.G.; Tsivadze, A.Y. Crown-substituted phthalocyanines—Components of molecular ionoelectronic materials and devices. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 59, 1635–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunin, D.A.; Martynov, A.G.; Gvozdev, D.A.; Gorbunova, Y.G. Phthalocyanine aggregates in the photodynamic therapy: Dogmas, controversies, and future prospects. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, G.; Vázquez, P.; Agulló-López, F.; Torres, T. Phthalocyanines and related compounds: Organic targets for nonlinear optical applications. J. Mater. Chem. 1998, 8, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, D.; Hanack, M. Phthalocyanines as materials for advanced technologies: Some examples. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2004, 8, 915–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, A.H.; Ribson, R.D.; Oyala, P.H.; Chen, G.Y.; Hadt, R.G. Understanding Covalent versus Spin–Orbit Coupling Contributions to Temperature-Dependent Electron Spin Relaxation in Cupric and Vanadyl Phthalocyanines. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 9252–9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmierczak, N.P.; Mirzoyan, R.; Hadt, R.G. The Impact of Ligand Field Symmetry on Molecular Qubit Coherence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17305–17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, B.; Schrage, B.R.; Ziegler, C.J.; Nemykin, V.N. Synthesis, spectroscopic, and electronic properties of new tetrapyrazinoporphyrazines with eight peripheral 2,6-diisopropylphenol groups. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2022, 27, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konarev, D.V.; Faraonov, M.A.; Kuzmin, A.V.; Khasanov, S.S.; Nakano, Y.; Norko, S.I.; Batov, M.S.; Otsuka, A.; Yamochi, H.; Saito, G.; et al. Crystalline salts of metal phthalocyanine radical anions [M(Pc˙3−)]˙− (M = CuII, PbII, VIVO, SnIVCl2) with cryptand(Na+) cations: Structure, optical and magnetic properties. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 6866–6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraonov, M.A.; Konarev, D.V.; Fatalov, A.M.; Khasanov, S.S.; Troyanov, S.I.; Lyubovskaya, R.N. Radical anion and dianion salts of titanyl macrocycles with acceptor substituents or an extended π-system. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 3547–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konarev, D.V.; Kuzmin, A.V.; Nakano, Y.; Faraonov, M.A.; Khasanov, S.S.; Otsuka, A.; Yamochi, H.; Saito, G.; Lyubovskaya, R.N. Coordination Complexes of Transition Metals (M = Mo, Fe, Rh, and Ru) with Tin(II) Phthalocyanine in Neutral, Monoanionic, and Dianionic States. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 1390–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finogenov, D.N.; Faraonov, M.A.; Kopylova, A.S.; Ivanov, T.E.; Romanenko, N.R.; Yakushev, I.A.; Konarev, D.V.; Stuzhin, P.A. Perchlorinated vanadyl tetrapyrazinoporphyrazine: Spectral, redox and magnetic properties. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 10067–10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissell, J.A.; Vaid, T.P.; Rheingold, A.L. Aluminum Tetraphenylporphyrin and Aluminum Phthalocyanine Neutral Radicals. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 2367–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Platel, R.H.; Tasso, T.T.; Furuyama, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Leznoff, D.B. Reducing zirconium(iv) phthalocyanines and the structure of a Pc4−Zr complex. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 13955–13961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal’pern, M.G.; Luk’yanets, E.A. Tetra-2,3-(5-tert-butylpyrazino) porphyrazines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1972, 8, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk’yanets, E.A. Electronic Spectra of Phthalocyanines and Related Compounds; NIITEKhIM: Cherkassy, Ukraine, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tokita, S.; Kai, N.; Osa, M.; Ohkoshi, T.; Kojima, M.; Nishi, H. Chemistry of Functional Dyes. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on the Chemistry of Functional Dyes, Osaka, Japan, 5–9 June 1989; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Gal’pern, M.G.; Kudrevich, S.V.; Novozhilova, I.G. Synthesis and spectroscopic properties of soluble aza analogs of phthalocyanine and naphthalocyanine. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1993, 29, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tverdova, N.V.; Giricheva, N.I.; Maizlish, V.E.; Galanin, N.E.; Girichev, G.V. Molecular Structure, Vibrational Spectrum and Conformational Properties of 4-(4-Tritylphenoxy)phthalonitrile-Precursor for Synthesis of Phthalocyanines with Bulky Substituent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tverdova, N.V.; Giricheva, N.I.; Maizlish, V.E.; Galanin, N.E.; Girichev, G.V. From conformational properties of 4-(4-Tritylphenoxy)phthalonitrile precursor to conformational properties of substituted phthalocyanines. Macroheterocycles 2022, 15, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogonin, A.E.; Kurochkin, I.Y.; Krasnov, A.V.; Malyasova, A.S.; Kuzmin, I.A.; Tikhomirova, T.V.; Girichev, G.V. Gas-Phase Structure of 4-(4-hydroxyphenylazo)phthalonitrile—Precursor for Synthesis of Phthalocyanines with Macrocyclic and Azo Chromophores. Macroheterocycles 2024, 17, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Gai, L.; Zheng, Y.-X.; Shen, Z.; Lu, H.; Guo, Z. Helical β-isoindigo-Based Chromophores with B−O−B Bridge: Facile Synthesis and Tunable Near-Infrared Circularly Polarized Luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eu, S.; Katoh, T.; Umeyama, T.; Matano, Y.; Imahori, H. Synthesis of sterically hindered phthalocyanines and their applications to dye-sensitized solar cells. Dalton Trans. 2008, 40, 5476–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyer, W. Okta-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-tetrapyrazinoporphyrazin und davon abgeleitete Metallkomplexe. J. Prakt. Chem. 1994, 336, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinina, T.V.; Trashin, S.A.; Borisova, N.E.; Boginskaya, I.A.; Tomilova, L.G.; Zefirov, N.S. Phenyl-substituted planar binuclear phthalo- and naphthalocyanines: Synthesis and investigation of physicochemical properties. Dye. Pigment. 2012, 93, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovkov, N.Y.; Akopov, A.S. Acid-base properties of complexes of group III elements with tetra-4-tert-butylphthalocyanine. Coord. Chem. 1987, 13, 1358–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Finogenov, D.N.; Lazovskiy, D.A.; Kopylova, A.S.; Zhabanov, Y.A.; Stuzhin, P.A. Spectral-luminescence, redox and photochemical properties of Al III, Ga III and In III complexes formed by peripherally chlorinated phthalocyanines and tetrapyrazinoporphyrazines. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2023, 27, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdoush, M.; Ivanova, S.S.; Koifman, O.I.; Kos’kina, M.; Pakhomov, G.L.; Stuzhin, P.A. Synthesis, spectral and electrochemical study of perchlorinated tetrapyrazinoporphyrazine and its AlIII, GaIII and InIII complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2016, 444, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuzhin, P.A. Azaporphyrins and Phthalocyanines as Multicentre Conjugated Ampholites. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 1999, 3, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçeşmeci, İ.; Koca, A.; Gül, A. Synthesis and electrochemical and in situ spectroelectrochemical characterization of manganese, vanadyl, and cobalt phthalocyanines with 2-naphthoxy substituents. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 5102–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ou, Z.; Chen, N.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Shao, J.; Kadish, K.M. Synthesis, spectral and electrochemical characterization of non-aggregating α-substituted vanadium(IV)-oxophthalocyanines. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2005, 9, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, A.B.P.; Licoccia, S.; Magnell, K.; Minor, P.C.; Ramaswamy, B.S. Mapping of the Energy Levels of Metallophthalocyanines via Electronic Spectroscopy, Electrochemistry, and Photochemistry. In Electrochemical and Spectrochemical Studies of Biological Redox Components; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1982; pp. 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finogenov, D.N.; Koptyaev, A.I.; Eroshin, A.V.; Kopylova, A.S.; Nabasov, A.A.; Galanin, N.E.; Zhabanov, Y.A.; Stuzhin, P.A. Molecular and Electronic Structure, and Electrochemical Study of Oxometal(IV) Tetrabenzoporphyrins, [TBPM] (M = VO, TiO). Macroheterocycles 2024, 17, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Matsushita, M.M.; Ouchi, Y.; Kepenekian, M.; Robert, V.; Donzello, M.P.; Ercolani, C.; et al. Crystal Structure, Spin Polarization, Solid-State Electrochemistry, and High n-Type Carrier Mobility of a Paramagnetic Semiconductor: Vanadyl Tetrakis(thiadiazole)porphyrazine. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurovich, P.I.; Mayo, E.I.; Forrest, S.R.; Thompson, M.E. Measurement of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energies of molecular organic semiconductors. Org. Electron. 2009, 10, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderne, R.E.; Borges, B.G.A.L.; Ávila, H.C.; von Kieseritzky, F.; Hellberg, J.; Koehler, M.; Cremona, M.; Roman, L.S.; Araujo, C.M.; Rocco, M.L.M.; et al. On the energy gap determination of organic optoelectronic materials: The case of porphyrin derivatives. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 1791–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.S.; Taveira, R.J.S.; Lima, C.F.R.A.C.; Mendes, A.; Santos, L.M.N.B.F. Optical band gaps of organic semiconductor materials. Opt. Mater. 2016, 58, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.M.; Curiac, C.; Delcamp, J.H.; Fortenberry, R.C. Accurate determination of the onset wavelength (λonset) in optical spectroscopy. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2021, 265, 107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagalov, E.V.; Pogonin, A.E.; Kiselev, A.N.; Syrbu, S.A.; Maizlish, V.E. New dinitrile: Synthesis, structure, and spectra. ChemChemTech 2023, 66, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tverdova, N.V.; Girichev, G.V.; Krasnov, A.V.; Pimenov, O.A.; Koifman, O.I. The molecular structure, bonding, and energetics of oxovanadium phthalocyanine: An experimental and computational study. Struct. Chem. 2013, 24, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, R.F.; Griffiths, C.H.; Troup, J.M. Crystal structure of vanadyl phthalocyanine, phase II. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1980, 11, 2300–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, H.; Yamada, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Takezoe, H.; Fukuda, A. Electric quadrupole second-harmonic generation spectra in epitaxial vanadyl and titanyl phthalocyanine films grown by molecular-beam epitaxy. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Xu, C.; Gao, J. A DFT and TD-DFT study on electronic structures and UV-spectra properties of octaethyl-porphyrin with different central metals(Ni, V, Cu, Co). Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Learmonth, T.; Wang, S.; Matsuura, A.Y.; Downes, J.; Plucinski, L.; Bernardis, S.; O’Donnell, C.; Smith, K.E. Electronic structure of the organic semiconductor vanadyl phthalocyanine (VO-Pc). J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 1276–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, R.A.; Mathpal, M.C.; Ruiz-Tagle, C.; Alvarado, V.H.; Pinto, F.; Martínez, L.J.; Gence, L.; Garcia, G.; González, I.A.; Maze, J.R. Photophysics of a single quantum emitter based on vanadium phthalocyanine molecules. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 29447–29457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, J.; Stillman, M.J. Assignment of the optical spectra of metal phthalocyanines through spectral band deconvolution analysis and zindo calculations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 219–221, 993–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogonin, A.E.; Eroshin, A.V.; Knyazeva, A.A.; Petrova, U.A.; Rychikhina, E.D.; Giricheva, N.I.; Zhabanov, Y.A. Molecular and electronic structure of Si (IV), Ge (IV), Sn (IV), Pb (IV) porphyrazines: DFT-study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2025, 1249, 115264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliznev, V.V.; Pogonin, A.E.; Ischenko, A.A.; Girichev, G.V. Vibrational Spectra of Cobalt (II), Nickel(II), Copper(II), Zinc(II) Etioporphyrins-II, MN4C32H36. Macroheterocycles 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.Q.E.; de Visser, S.P. Reactivity patterns of vanadium (IV/V)-oxo complexes with olefins in the presence of peroxides: A computational study. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 16899–16910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Patra, R.; Rath, S.P. Axial ligand coordination in sterically strained vanadyl porphyrins: Synthesis, structure, and properties. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 9848–9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, K.I.; Tazawa, S.; Sugiura, K.I. Oxo (porphyrinato) vanadium (IV) as a standard for geoporphyrins. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2016, 439, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chaudhary, N.; Sankar, M.; Maurya, M.R. Electron deficient nonplanar β-octachlorovanadylporphyrin as a highly efficient and selective epoxidation catalyst for olefins. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 17720–17729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernzerhof, M.; Scuseria, G.E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 5029–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, B.P.; Altarawy, D.; Didier, B.; Gibson, T.D.; Windus, T.L. New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnevskiy, Y.V.; Zhabanov, Y.A. New implementation of the first-order perturbation theory for calculation of interatomic vibrational amplitudes and corrections in gas electron diffraction. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2015, 633, 012076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, T.; Tew, D.P.; Handy, N.C. A new hybrid exchange-correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S. A simplified time-dependent density functional theory approach for electronic ultraviolet and circular dichroism spectra of very large molecules. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1040–1041, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurko, G.A. Chemcraft—Graphical Software for Visualization of Quantum Chemistry Computations. Available online: https://www.chemcraftprog.com (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- O’boyle, N.M.; Tenderholt, A.L.; Langner, K.M. cclib: A library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | λabs (Q0–Qn), nm (cm−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 0 | n = 1 | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 4 | |

| [Al(Cl)PcCl8] * | 681 | 710 (600) | 734 (1060) | 774 (1764) | 810 (2339) |

| [Ga(OH)PcCl8] * | 682 | - | 728 (926) | 774 (1740) | 811 (2330) |

| [In(OH)PcCl8] * | 688 | - | - | - | 818 (2289) |

| [Al(OH)Pc(t-Bu)4] # | 691 | 718 (540) | 740 (949) | 805 (2044) | 825 (2344) |

| [Ga(OH)Pc(t-Bu)4] # | 693 | 718 (510) | 744 (980) | 802 (1970) | 835 (2410) |

| [In(OH)Pc(t-Bu)4] # | 695 | 727 (650) | 745 (960) | 799 (1870) | 830 (2320) |

| [VOPc(t-BuPh)8] | 722 | 777(980) | 801(1366) | - | - |

| [VOTPyzPz(t-BuPh)8] | 662 | 687(550) | - | - | - |

| Compound | Reduction Potentials E1/2, V | Solvent|Reference Electrode | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||

| (t-BuPh)2PN | −1.57 | - | - | DCM|Ag/AgCl | This Work |

| (t-BuPh)2PDC | −1.13 | - | - | DCM|Ag/AgCl | This Work |

| VOPc(t-BuPh)8 | −0.58 | −0.90 | - | DCM|Ag/AgCl | This Work |

| VOTPyzPz(t-BuPh)8 | −0.19 | −0.49 | −0.77 | DCM|Ag/AgCl | This Work |

| VOTPyzPzCl8 | −0.19 | −0.52 | −0.83 | DMF|Ag/AgCl | [18] |

| VOPc(NaphtO)4 | −0.64 | −0.98 | −1.83 | DCM|SCE | [36] |

| VOPc(t-Bu)2C6H3O)4 | −0.51 | −0.97 | −1.94 | DMF|SCE | [37] |

| VOPc(C8H17O)4 | −0.62 | −1.12 | −2.07 | DMF|SCE | [37] |

| VOPc | −0.58 | −1.08 | - | DMF | [38] |

| VOTBP | −1.19 | −1.42 | - | DMF|Ag/AgCl | [39] |

| VOTTDPz | −0.4 | - | - | Thin film|Ag/AgCl | [40] |

| Compound | ELUMO a, eV | OEG or Δ(HOMO-LUMO), eV | EHOMO b, eV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVA c | PBE0 d | UV-Vis e | PBE0 d | Exp f | PBE0 d | |

| (t-BuPh)2PN | −2.31 | −2.36 | 3.49 | 4.52 | −5.80 | −6.88 |

| (t-BuPh)2PDC | −2.83 | −2.76 | 3.10 | 4.18 | −5.93 | −6.94 |

| VOPc(t-BuPh)8 | −3.49 | −2.92 | 1.66 | 2.25 | −5.15 | −5.17 |

| VOTPyzPz(t-BuPh)8 | −3.95 | −3.29 | 1.81 | 2.45 | −5.76 | −5.74 |

| Parameters a | PN | Ph2PN | (t-BuPh)2PN | PDC | Ph2PDC | (t-BuPh)2PDC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | C2v | C2 | C2 | C2v | C2 | C2 |

| C5-C6 | 1.388 | 1.407 | 1.408 | 1.393 | 1.423 | 1.425 |

| X1-C6 | 1.384 | 1.391 | 1.391 | 1.321 | 1.326 | 1.326 |

| X1-C2 | 1.392 | 1.388 | 1.389 | 1.329 | 1.325 | 1.326 |

| C2-C3 | 1.404 | 1.402 | 1.402 | 1.403 | 1.398 | 1.398 |

| C2-CCN | 1.425 | 1.424 | 1.424 | 1.432 | 1.431 | 1.431 |

| CCN-NCN | 1.151 | 1.151 | 1.151 | 1.150 | 1.150 | 1.150 |

| C6-C1Ph | - | 1.478 | 1.476 | - | 1.472 | 1.470 |

| C1Ph-C2Ph | - | 1.394 | 1.395 | - | 1.394 | 1.395 |

| C3Ph-C4Ph | - | 1.388 | 1.397 | - | 1.388 | 1.397 |

| C4Ph-C1Bu | - | - | 1.522 | - | - | 1.522 |

| φ1 = φ2 b | - | 50.1 | 49.5 | - | 38.1 | 37.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Finogenov, D.N.; Pogonin, A.E.; Zhabanov, Y.A.; Ksenofontova, K.V.; Parfyonova, D.Y.; Eroshin, A.V.; Stuzhin, P.A. Influence of Aza-Substitution on Molecular Structure, Spectral and Electronic Properties of t-Butylphenyl Substituted Vanadyl Complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020606

Finogenov DN, Pogonin AE, Zhabanov YA, Ksenofontova KV, Parfyonova DY, Eroshin AV, Stuzhin PA. Influence of Aza-Substitution on Molecular Structure, Spectral and Electronic Properties of t-Butylphenyl Substituted Vanadyl Complexes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020606

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinogenov, Daniil N., Alexander E. Pogonin, Yuriy A. Zhabanov, Ksenia V. Ksenofontova, Dominika Yu. Parfyonova, Alexey V. Eroshin, and Pavel A. Stuzhin. 2026. "Influence of Aza-Substitution on Molecular Structure, Spectral and Electronic Properties of t-Butylphenyl Substituted Vanadyl Complexes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020606

APA StyleFinogenov, D. N., Pogonin, A. E., Zhabanov, Y. A., Ksenofontova, K. V., Parfyonova, D. Y., Eroshin, A. V., & Stuzhin, P. A. (2026). Influence of Aza-Substitution on Molecular Structure, Spectral and Electronic Properties of t-Butylphenyl Substituted Vanadyl Complexes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020606